Radical as a way of Being: Inaugural Contemporary Fellow Nalini Malani at London's National Gallery

Radical as a way of Being: Inaugural Contemporary Fellow Nalini Malani at London's National Gallery

Radical as a way of Being: Inaugural Contemporary Fellow Nalini Malani at London's National Gallery

Radical as a way of Being:

Inaugural Contemporary Fellow Nalini Malani at London's National Gallery

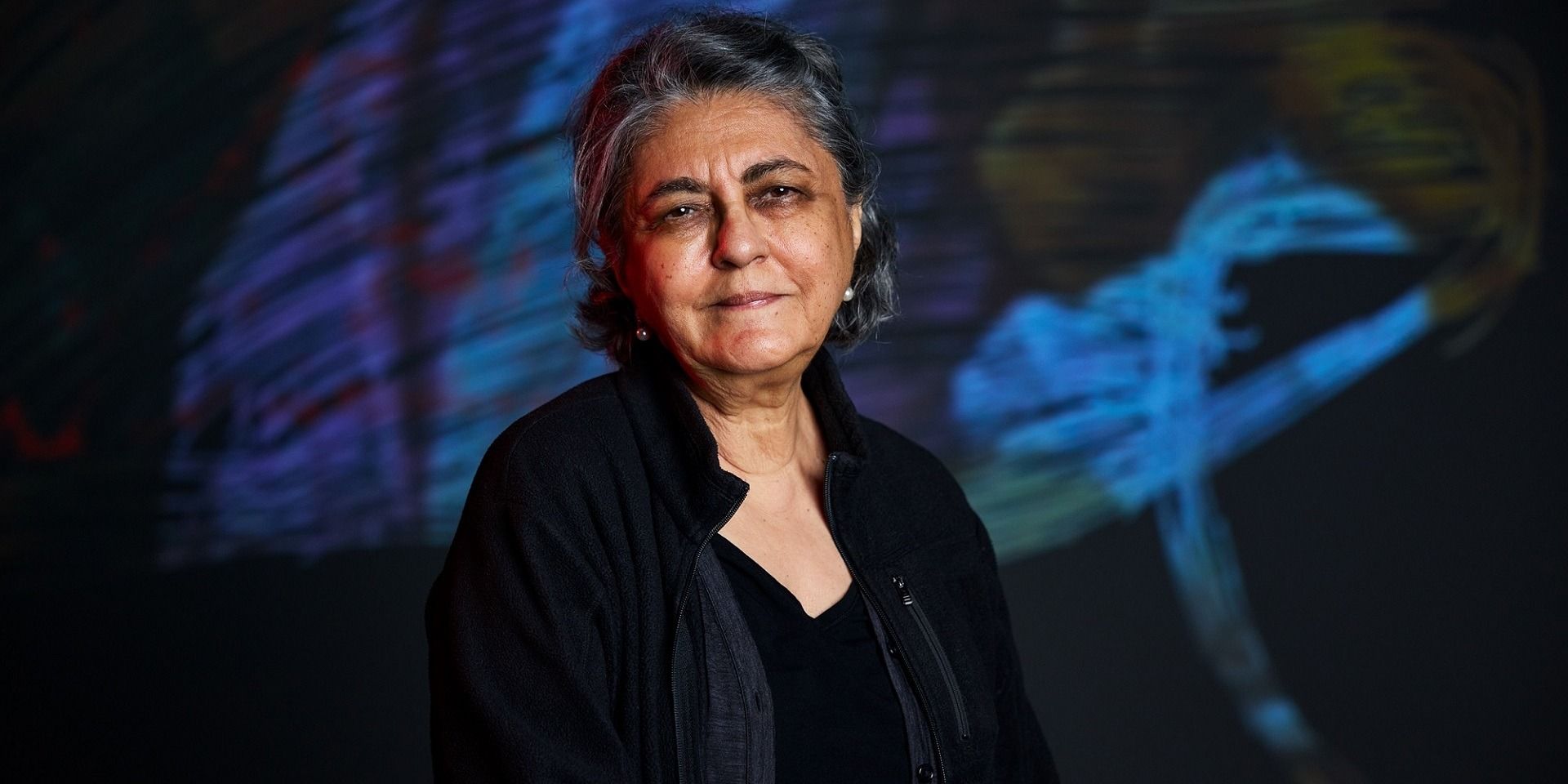

Nalini Malani in front of her work My Reality is Different, 2022; Animation chamber, 9-channel installation, sound: 25.15 mins © Nalini Malani; Photo: Luke Walker

The neo-classical halls of the National Gallery lend a certain hallow to the artworks in gilded frames. Architect William Wilkins’ ‘Temple of the Arts’, was meant to inspire the contemporary arts through historical example—a mission that has been adapted by the newly established National Gallery’s Contemporary Fellowship. Indian artist, Nalini Malani, the first ever recipient of the fellowship, has taken over more than 40 meters of wall space to explore/disrupt the status quo between the ‘inspiration’ and the ‘inspired’ through a work that engages with the prestigious collection at the National Gallery and the Holburne Museum, Bath. The work, titled My Reality is Different, is on display at the National Gallery until the 10th of June 2023 and is accompanied by a fully illustrated catalogue.

|

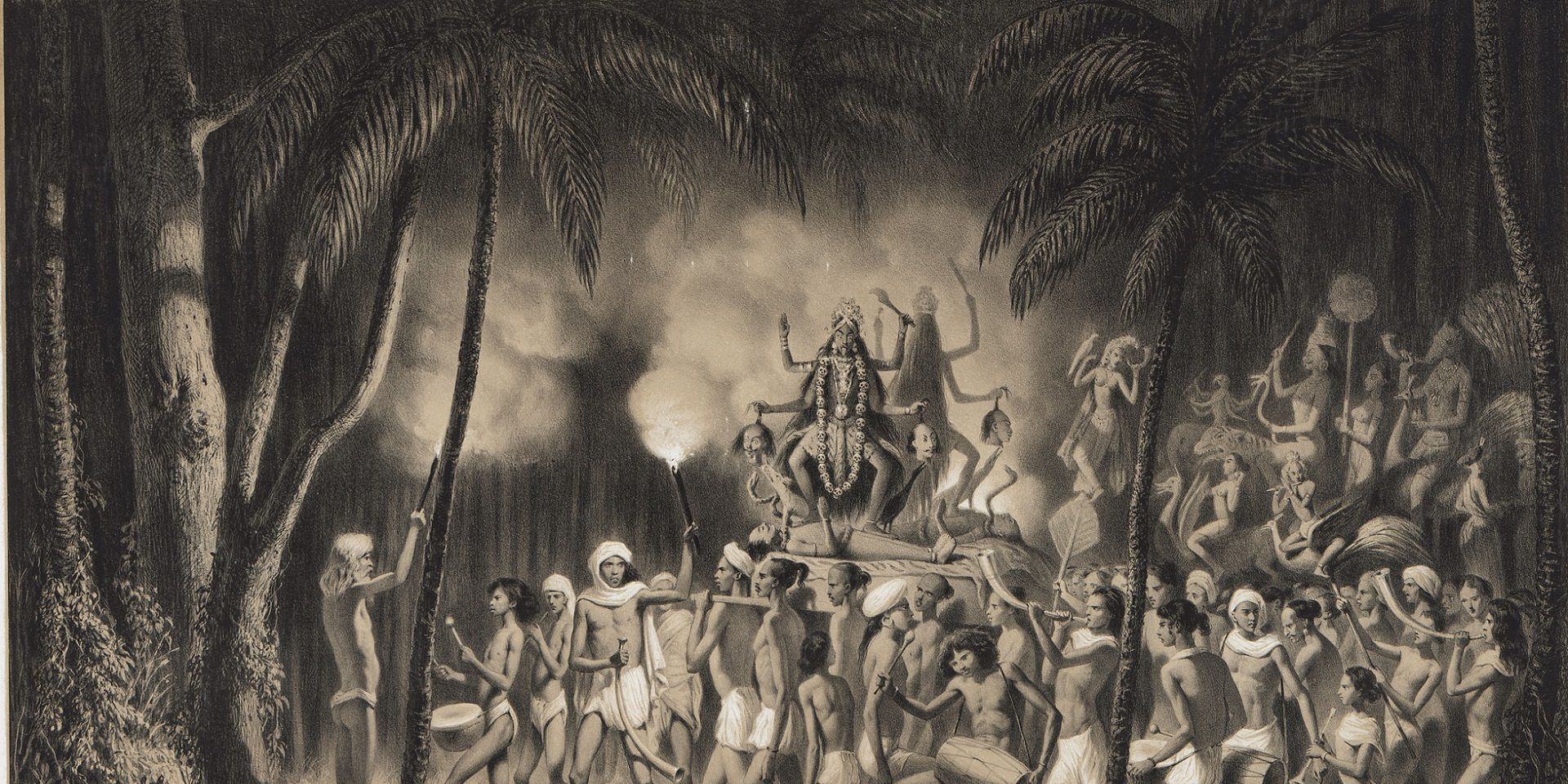

The National Gallery at London, United Kingdom. Image credit: Wikimedia Commons |

Malani calls My Reality is Different an ‘animation chamber’, a term coined by her to describe a medium of her own experimentation. Finger-drawn iPad animations, intervene in an idiosyncratic selection of twenty-five paintings, immersing the viewer in a kaleidoscopic panorama of nine video projections on loop. The paintings, which include works by Caravaggio, Holbein, Rubens, and Bronzino, are made to emerge and then enlivened and effaced by Malani’s touch—described by her in the catalogue essay as a ‘despoiling’ and ‘desecration’ of the works. Interspersed within each loop are full-screen fictional portraits of people of colour whose labour props up the global economic networks. Their faces are imprisoned behind colourful stock market graphs. The video projections are accompanied by a soundscape that is as layered as the projections. Cassandra—the cursed seer from Greek Mythology, doomed to never have her prophecies believed—voices ominous tellings of the Trojan war. Her voice is punctuated by the sounds of a thunderous ocean storm and musical references to the song Rule Britannia! The video projections are looped but remain un-synced so that every viewing is a unique permutation of paintings, animations, and sound, offering a different interpretation each time. Throughout the work we see and experience Malani’s questioning of the world order—a challenging of orthodoxy, colonial dominance, patriarchal subjugation, and a teleological and a linear gaze. The ‘disruption’ of the paintings becomes a productive intervention into historicism. This colourfully-complex medley is described by Malani as being akin to entering her brain. A statement which reflects the observation that this work is a manifestation and maturity of various facets of Malani’s decades long art practice.

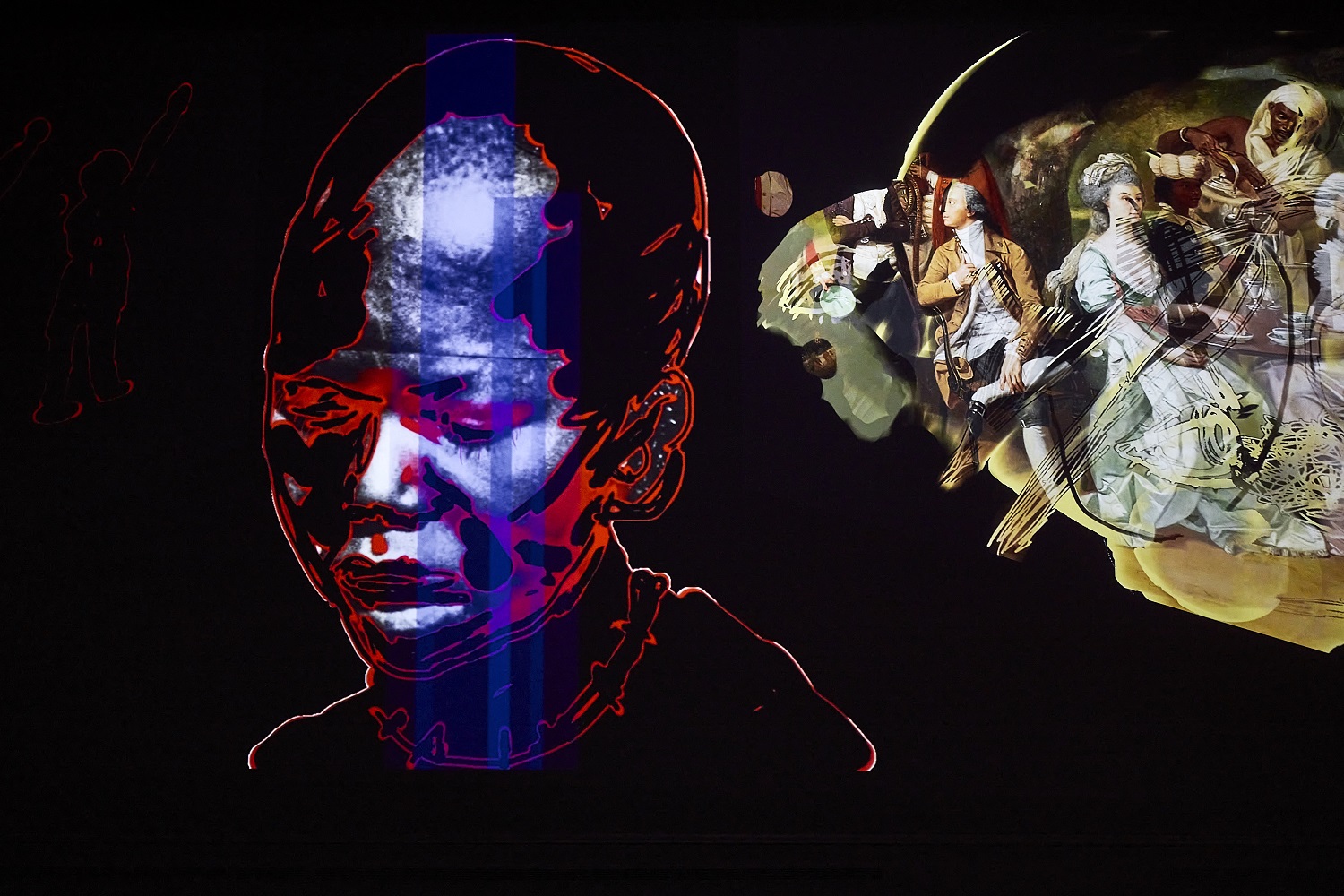

Nalini Malani, My Reality is Different, 2022 (detail); Animation chamber, 9-channel installation, sound: 25.15 mins © Nalini Malani; Photo: Luke Walker

A graduate of Sir J. J. School of Art, Bombay (now, Mumbai), Nalini Malani’s practice includes narrative painting, mixed media, moving image, performance, theatre, and installation.Her work has stubbornly repelled any neat distinctive category applied to it in terms of medium, technique or form. What has been a connecting thread in her practice, however, is a commitment to socio-political relevance. In 1985 she was a part of organising and exhibiting in, Through the Looking Glass, the first exhibition dedicated solely to women artists in India alongside Nilima Sheikh, Arpita Singh, and Madhvi Parekh.

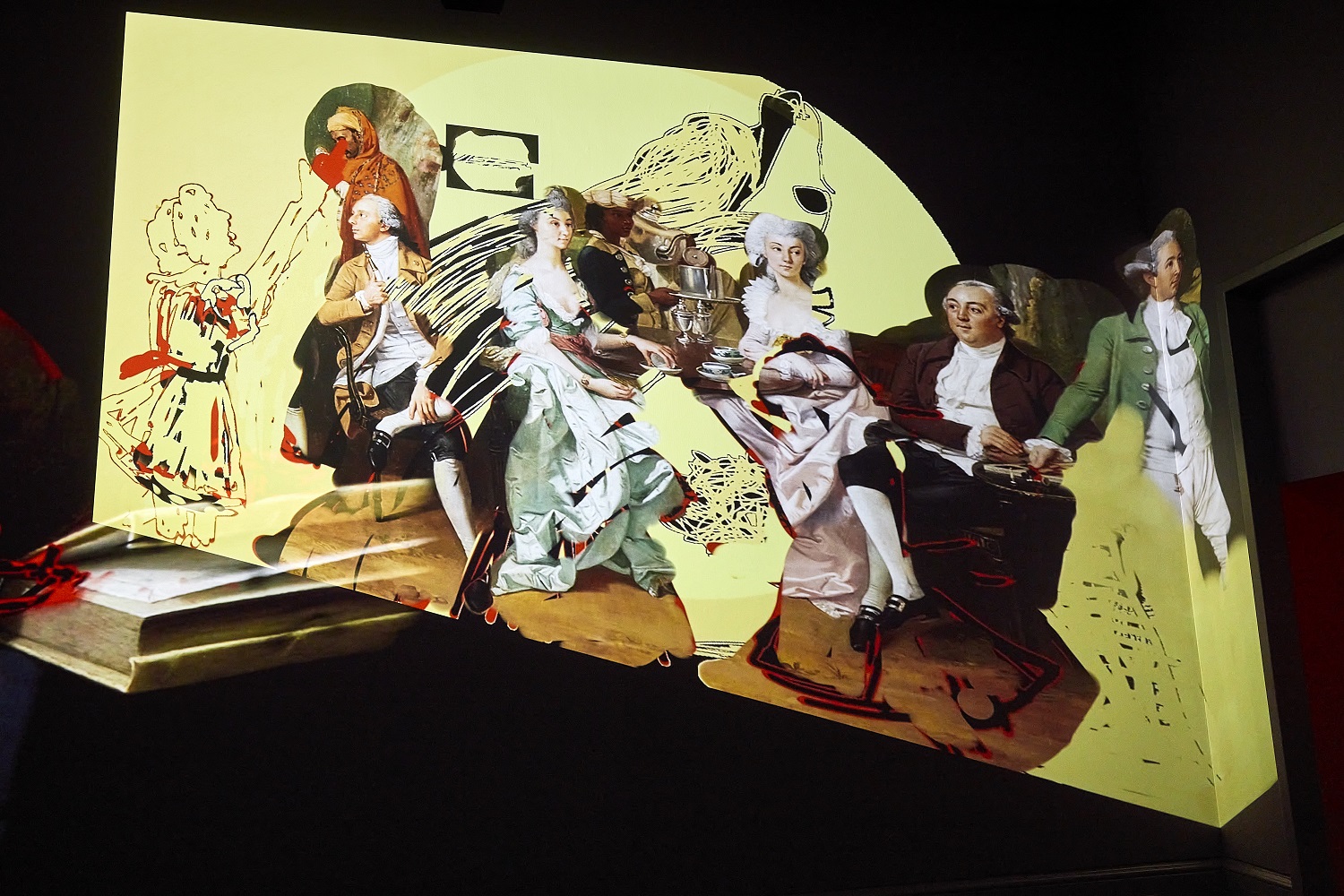

Nalini Malani, My Reality is Different, 2022 (detail); Animation chamber, 9-channel installation, sound: 25.15 mins © Nalini Malani; Photo: Luke Walker

Her narrative works often delved into mythology and exhibited a distinct feminist voice, subverting the narratives of characters like Sita or Radha. Her contribution to the moving image medium retained the feminist gaze and frequently navigated issues of caste like in her film Taboo. Active engagement with caste, class, religion, and gender has had a constant presence in her oeuvre. A consistent commitment towards engaging with politics in her art has led to her being popularly described often as an ‘activist artist’. Her practice has, in the past, fearlessly pushed the boundaries between art and politics by exploring complex, violent, and traumatic issues such as the Partition, the Babri Masjid demolition and the 2002 Gujarat riots. An earlier animation chamber by her titled, Can You Hear Me?(2018), was on Asifa Bano, an eight-year-old Muslim girl who was gang-raped and murdered by Hindu men in India—a work that had a profound effect on not just viewers but also on the discourse on art and politics in India.

Nalini Malani, My Reality is Different, 2022 (detail); Animation chamber, 9-channel installation, sound: 25.15 mins © Nalini Malani; Photo: Luke Walker

Nalini Malani’s practice has proven to be intersectional in both ideology and medium. Previously, she had used reverse painting on rotating mylar cylinders to depict narratives, thus disrupting the notion of two-dimensionality in painting through dynamic movement. This engagement with painting is revisited in My Reality is Different, where the large and often awe-inspiring canvases of the Old Masters stop being static, both in form and temporality. She has also engaged with the relationship between performance and painting through her ephemeral murals. Voiced by Alaknanda Samarth, the soundtrack of Cassandra surrounding the viewer in the animation chamber at the National Gallery is an inheritance of the many interactions Malani’s works have had with theatre and poetry. Earlier in her career, Malani had also collaborated with Samarth on a theatrical project on Medea from Greek mythology. Malani’s practiced deployment of a lexicon of cross-cultural imagery in My Reality is Different, is representative of an oeuvre that has maintained a refusal to align with and accept the socio-political status quo in any context.

Nalini Malani, My Reality is Different, 2022 (detail); Animation chamber, 9-channel installation, sound: 25.15 mins © Nalini Malani; Photo: Luke Walker

At the National Gallery, Malani’s Reality makes the violence of the Elders’ gaze in Guido Reni’s Susannah and the Elders palpable via streaks of red spattered across Susannah’s nude figure in one of the loops. While, in The Ambassadors by Hans Holbein the Younger, red gashes spurt from the globe, a symbol of colonial dominance, while a black stick figure rests dejectedly upon the music book. Elsewhere, the African monarch on the side in Bruegel the Elder’s The Adoration of the Kings, is brought into the spotlight. For Malani, My Reality is Different, is not just a response to the paintings that she ‘defiles’, it is also an engagement with the history of these collections. The acquisition of the Old Masters she makes the canvas of her animations, have direct links to wealth amassed by the exploitation of slavery and indentured labour. The National Gallery has acknowledged as much in a published research project in 2021, writes Malani in the catalogue essay. The great grandfather of Sir William Holburne, whose patronage she has interacted with in the three paintings from the Holburne Museum, was the owner of West Indian plantations—evidenced by an 18th century ledger from Barbados in the Museum’s collection. In this work Malani interrogates ‘not the artists, but the merchants who bought these paintings, and how the bourgeoisie in Britain looked at the dark races'. The fictitious faces obscured by colourful financial data and the animated figures disrupting the hallowed paintings, bring the history of these collections—the indelible link between labour and patronage, and the colonial narrative—onto the contemporary stage.

|

Some of the works referenced or 'desecrated' by Malani includes famous masterpieces that are hanging at the National Gallery, such as Guido Reni's Susannah and the Elders, painted 1620-1625. Image credit: Wikimedia Commons |

|

Pieter Bruegel the Elder, The Adoration of the Kings, 1564, Oil on oak panel. Image credit: Wikimedia Commons |

My Reality is Different, has been lauded as radical, an adjective that is hardly unfitting. And yet, the radicalism and subversions of hegemonic gaze and narratives in this work are not limited to interpretation but are embedded within the medium, the form, and the context. Nalini Malani had once responded to her work being called political with a reminder that the water we drink is political. For her, and consequently her practice, radical is a way of being.

Nalini Malani, My Reality is Different, 2022 (detail); Animation chamber, 9-channel installation, sound: 25.15 mins © Nalini Malani; Photo: Luke Walker

Further Reading:

Will Cooper, Priyesh Mistry et al. ‘Nalini Malani: My Reality is Different Catalogue’. National Gallery Global. December 2022.

Maya Jaggi. ‘Nalini Malani at the National Gallery, review — acts of creative desecration’. Financial Times 15 March 2023. Accessed 25 April 2023

Kabir Jhala, 'The past is being weaponised': Nalini Malani's anti-fascist animations come to the Whitechapel Gallery’. The Art Newspaper 18 September 2020. Accessed 25 April 2023.

DAG Recommends is a series where we highlight significant cultural and artistic events from across the world.