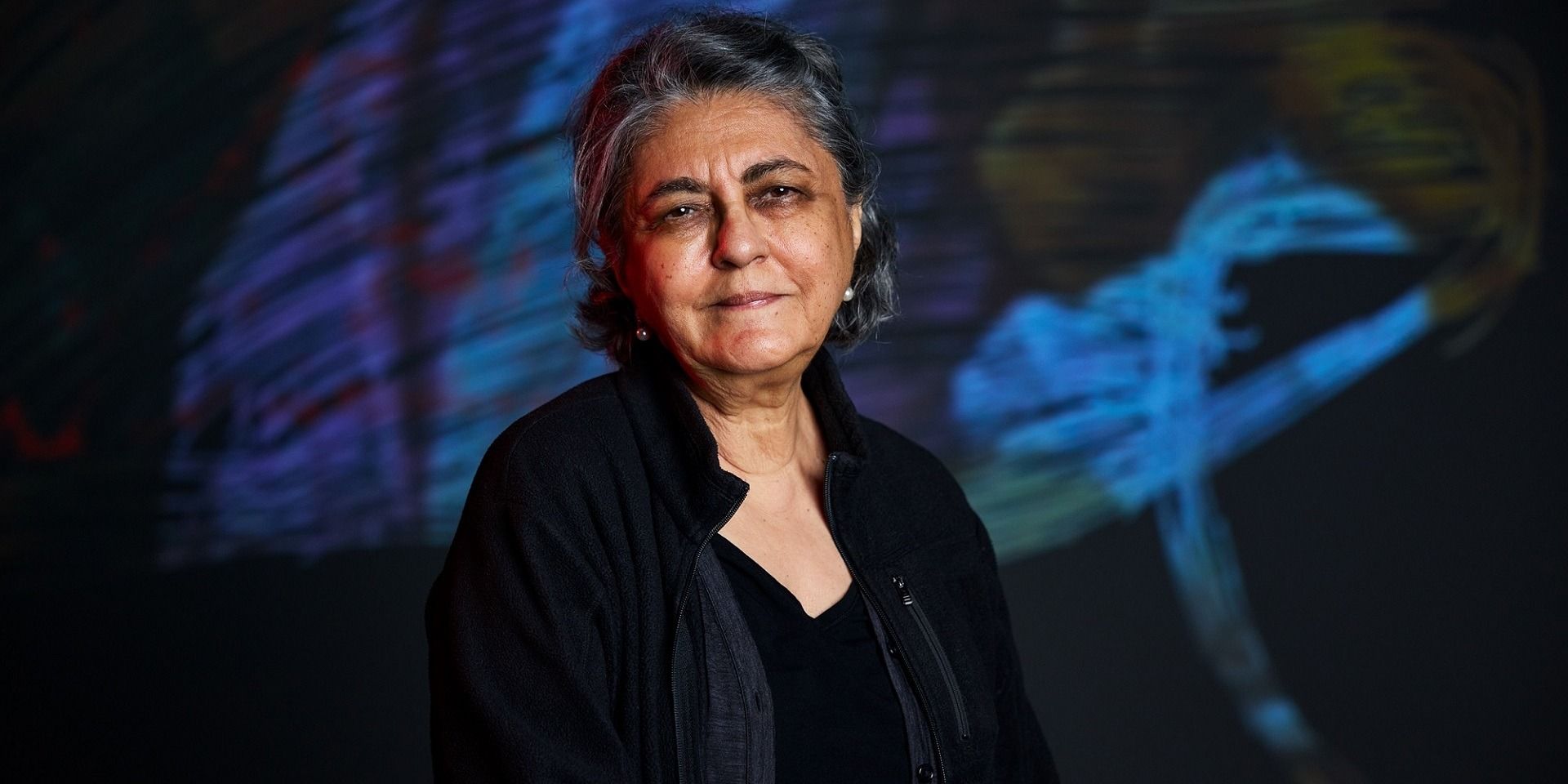

A Russian Abroad: Alexei Soltykoff's Indian Views

A Russian Abroad: Alexei Soltykoff's Indian Views

A Russian Abroad: Alexei Soltykoff's Indian Views

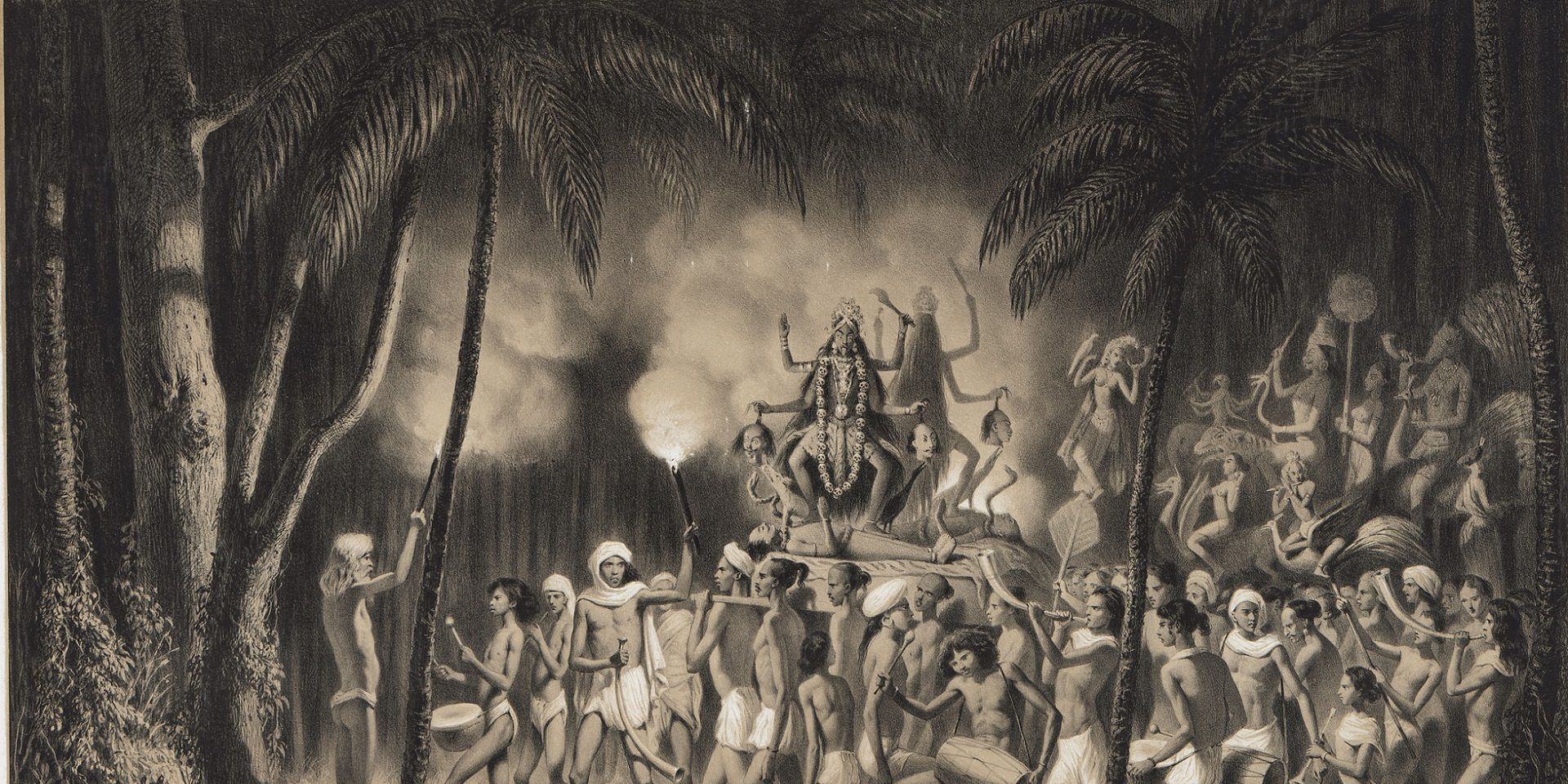

Prince Alexis Soltykoff, Procession de la Déesse Kali (Procession of the Goddess Kali) (detail), 1841, Lithograph on paper, 19.5 × 27.2 in. Collection: DAG

One of the cornerstones of DAG’s historic exhibition on the goddess Kali is a dark and mysterious work by a little-known artist called Alexis Soltykoff (1806—1859). The lithographic print, engraved by Louis Henri de Rudder, depicts a celebration to the goddess Kali, undertaken by a band of passionate devotees—seemingly emerging from the cavernous depths of a forest that is illuminated by makeshift torches. Who was this artist and how did he come to make this work?

Prince Alexis Soltykoff was a Russian artist and traveller who made significant contributions to the worlds of art and diplomacy, especially through his travels in Central Asia, Europe and India. Born in St. Petersburg, he embarked on voyages to India twice in the decade of the 1840s, capturing the essence of Indian life through his paintings and writings. Soltykoff's travels to India resulted in notable works such as Letters from India, which was accompanied by his sketches and drawings, published in France in 1849. It provided a vivid portrayal of Indian scenes and characters. His artistic talent and keen observations allowed him to document the cultural nuances and landscapes of India with great detail and authenticity, and these drawings were known widely across Europe.

|

Prince Alexis Soltykoff, Habitants de l'Inde dessinés d'après nature, 1853, Lithograph on paper, 20.7 X 28.7 X 2.7 in. Collection: DAG |

Prince Soltykoff's decision to travel to India was driven by his desire to explore new landscapes, meet new people, and learn about their customs. He retired from the diplomatic service at the age of 34 to devote himself to his hobbies, including painting and travel. Before embarking on his journey, Soltykoff spent time in Paris, where he planned his trip and became more seriously engaged in painting and drawing. Soltykoff's journey to India in 1841 was influenced by his interest in the country, despite not having been there before. Although Russian travellers had a long connection with the Indian subcontinent, they are usually held to form a separate tradition from that of European travellers from the early modern period. Russia locates itself ambiguously across the pan-continental political imaginaries of Asia and Europe, and their imperial aims have consistently, at least since the nineteenth century, dictated colonial policy in the Indian subcontinent. Thus, there was always bound to be a certain element of rivalry in the gaze deployed by a Russian traveller when they made their way through domains held by the British colonial authority, as was the case during Soltykoff’s travels.

Prince Alexis Soltykoff, Intérieur du Couvent de Condgeveram, à 40 Milles de Madras, 1841, Lithograph tinted with watercolour on paper, 21.0 X 25.2 in. Collection: DAG

Commenting on the rich history of Russian travellers to India, Evgenia Vanina writes, ‘Russians visited India and wrote about it, standing out noticeably against the general European background perhaps due to Russia’s centuries-old experience of living in the neighbourhood and in one state with Asian peoples… Russian translations (first from European translations and subsequently from Sanskrit originals) of the “Bhagwat Gita”, “Shakuntala” and fragments of the “Ramayana” and “Mahabharata” were published. The first Indologists studying Sanskrit and other Indian languages, as well as the first narrations of major events in Indian history, appeared in Russia. It was precisely under those circumstances that Prince Alexei D. Saltykov made his journeys to India.’ Even if there is a slight exaggeration in her claims about the ‘first Indologists’, it attests to a long-standing interest among Russian artists for the Indian subcontinent, which would continue over the next few generations with Vasily Vereshchagin, whose majestic tableau titled The Elephant Procession: The Prince of Wales Visiting Jaipur on February 4, 1876 now hangs at Kolkata’s Victoria Memoria Hall or Nicholas Roerich, known for his deep spiritual and artistic contributions to Indian life, which has made him one of the nine ‘national treasure’ artists of India.

|

Vasily Vereshchagin, The Elephant Procession: The Prince of Wales Visiting Jaipur on February 4, 1876. Image courtesy: Wikimedia Commons |

|

Nicholas Roerich, Trees By a Lake, Oil, enamel and ink on canvas, 18.0 x 10.0 in. Collection: DAG |

Soltykoff travelled to India on the Berenice, a steamboat of the East India Company, commanded by Captain A. J. Young. During his voyage, he interacted with various passengers, including French and English travellers who brought different perspectives that impacted him. Many of these perspectives would be reproduced in his letters, even as Soltykoff grew aware of the gaps in British or European knowledge production on India (compromised especially by its need to tie it up with questions of security and political administration). Upon arriving in India, Soltykoff visited Maharaja Shivaji at Tandjor (Tanjore) and experienced Indian royalty. He was described as a wealthy noble who dressed in fashionable Parisian attire during his time in India. His experiences in Mysore included staying at Dr. Bakey's house in the Nilgiri Mountains and observing local customs and cultural performances.

He is also known for his travels across the Himalayas in the north, at a time of great political tensions between the British and its northern and north-western neighbours like Nepal or Maharaja Ranjit Singh’s empire of the Punjab, with Afghanistan and the frontier provinces beyond it. While the prince lived in popular British enclaves like Simla, he ingratiated himself into the fashionable company of his time, which formed the colonial elite. However, due to his origins, he never fit in perfectly with them either—as evidenced by his letters. Even artistically, he felt isolated. In spite of the fact that the Daniells, William Hodges, the Frasers and other European travelling artists had already painted several picturesque views of the country, Soltykoff wanted to see other sights and paint different views. He tried to cultivate an alternative aesthetic appetite for the new landscapes he saw unfolding before his eyes. He did not want to show the country as a site of picturesque ruins, awaiting the touch of civilisation or progress—which supplied the mythic force to Britain’s colonial engine—or sketch examples of Britain’s technological beneficence to the country, like its infrastructure and the railways, which became more common following the decade of the 1850s. Instead, he sketched personal views of people, their religious customs and everyday work routines. His sketches of the forested hills in places like Simla and Mussoorie were similarly meant to act as visual notes to aid his memory of having lived in these places, and mixed with its people, rather than perfunctorily passing through them.

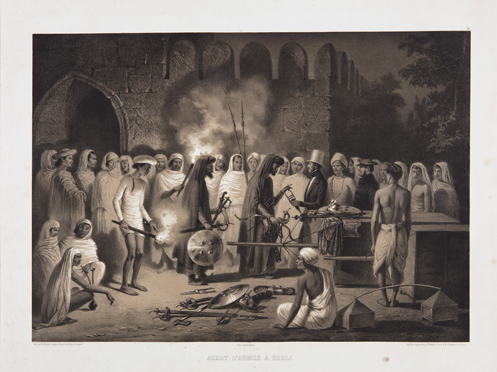

Prince Alexis Soltykoff, ACHAT D`ARMES A DELHI, 15.7 X 21.0 in. Collection: DAG

Emphasising the newness of the scenes he sketched and the loneliness of his efforts in an India dominated as much by colonial administrative politics as aesthetic norms, in one of his letters Soltykoff writes, ‘…I console myself with the thought that if I am destined to draw these wonders of nature I must set to work as conscientiously as possible. Otherwise I would be unworthy in your eyes and in my own. And here I am, armed with my pencil and sometimes it occurs to me that my sketches are unworthy of the majesty of the nature which surrounds me; yet I have painted myself into an exceptional corner: there are no other artists here and the pencil is my inspiration. One thing drives me to despair: the British absolutely do not understand a combination of lines which for me is a s necessary as the combination of sounds is for a musician. They are only satisfied with my work when I make a portrait of one of them and they look on the rest of my drawings as some sort of pretentious childishness.’ The musical metaphor employed by the artist explains his own use of delicate shading and chiaroscuro, the hallmark of his rhythmic visual style, which deepens the mystery of the landscape and its people without offering clear rules for domination or categorisation.

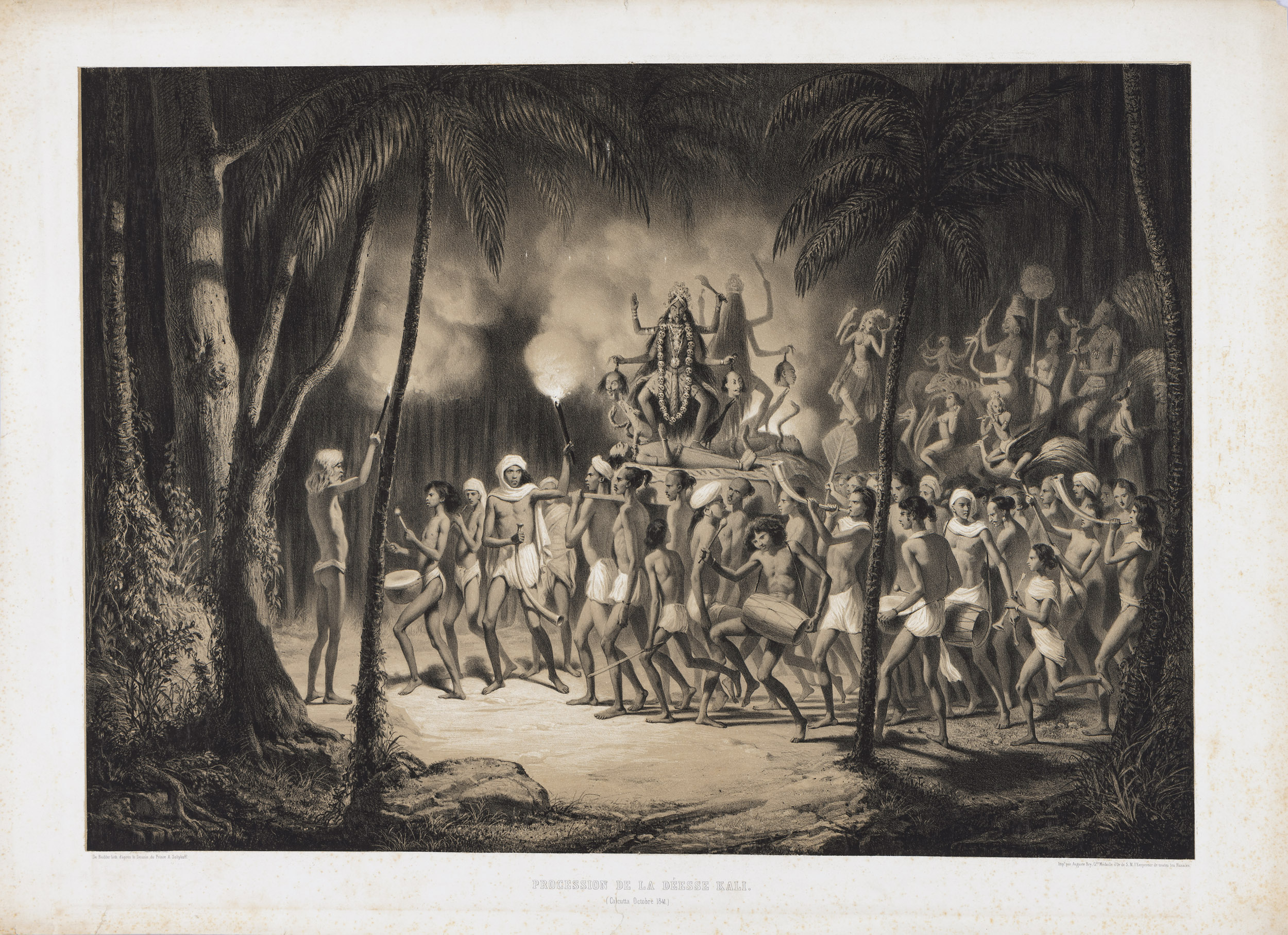

Prince Alexis Soltykoff, Procession de la Déesse Kali (Procession of the Goddess Kali), 1841, Lithograph on paper, 19.5 × 27.2 in. Collection: DAG

While it is suggested that his depiction of the Kali celebrations borrows from contemporary Thuggee cults’ celebrations to the goddess, it is also speculated that this image, soaked in the penumbral darkness of the forest, may have emerged from one of his travels to the small hamlets outside Simla. Irina Chelysheva writes, ‘In Saltykov’s letters we come across a temple dedicated to Goddess Kali (possibly in the village Kheri, near Simla) and not to Durga which, in principle, is not particularly contradictory, taking into account the fact that local inhabitants often identify with both hypostases. There, as far as it is possible to judge from his sketches, he was witness to a performance which he believed to be the dance of the mountain dwellers, attaching to the drawing an appropriate inscription. Indeed, judging by the attire of the dancers depicted, the artist was witness to a performance by the inhabitants of valleys, in all probability, who specially arrived in this place in order to participate in the said celebration or festival.’ If this indeed pertains to the image at hand, it also offers an intriguing link to the traditions of Kali puja as celebrated in Bengal and across north India. The stage-like setting of the scene, in a small clearing in the forest, opens our eyes onto a different performance of the traveller’s gaze—so common a building block in the body of knowledge regarding how India has unconcealed itself over the centuries—and initiates the viewer into a world of mysterious spiritual energy, emanating from its contained, picturesque landscape, even as the country’s temporal fortunes hung on a balance. The resistance, if not a triumph, of the spiritual—a theme returned to by Roerich in the following century—assumes a thematic core in Soltykoff’s vision as well.