How to Look at a Mountain: Views around Darjeeling

How to Look at a Mountain: Views around Darjeeling

How to Look at a Mountain: Views around Darjeeling

Abanindranath Tagore, Untitled (Darjeeling Market) (detail), wash and ink on postcard. Collection: DAG

How did Darjeeling become an enduring icon of romantic mountain art in the subcontinent?

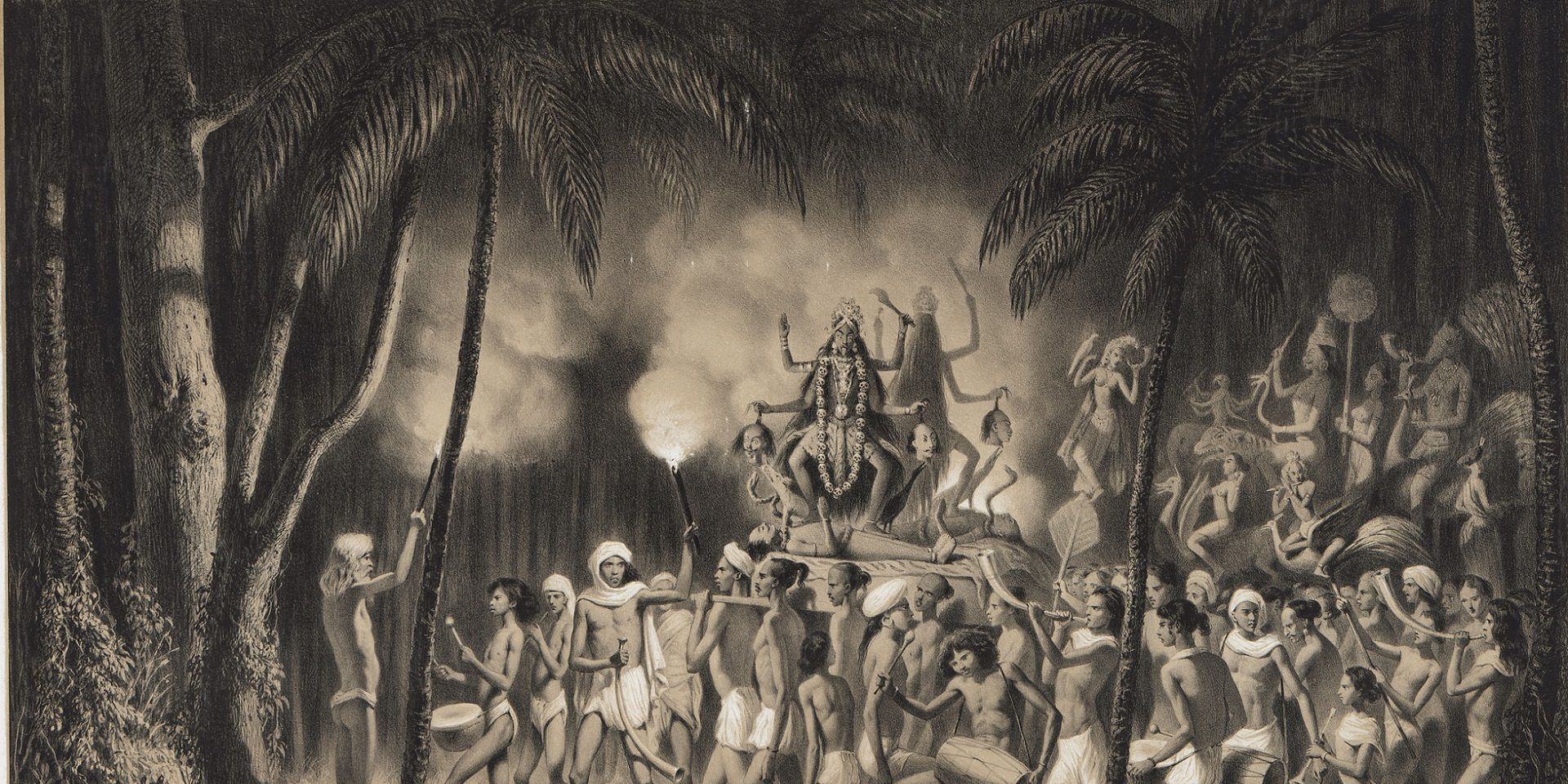

Darjeeling’s name derives from ‘Dorje’ which means ‘thunderbolts’ and ‘Ling’, which means the ‘place’, and collectively means ‘the land of thunderbolts’ in the Tibetan language. Most historical accounts trace the foundation of Darjeeling, now a hill town in the Indian state of West Bengal lodged between the Mechi and Teesta rivers, back to a mysterious deed grant that allowed the British a portion of the kingdom of Sikkim after 1835. The chogyal of Sikkim was forced to accept the terms of the colonial empire which allowed the latter to regard the ceded territory as their own. Why were such hill stations important for the colonial rulers? As Agastya Thapa has written, ‘During the 18th and 19th centuries, with the expansion of British commercial and territorial interests throughout the world, the establishment of colonial enclaves within tropical colonies served purposes like cantonments for the army, plantations for large-scale production of cash crops, supply stations for cheap labour and hill stations for British civilians and officials. These hill stations were special British conclaves which were landscaped from native terrains in order to make them conform to their ideal of picturesque beauty. Accordingly, Darjeeling, as one such hill station, came up in the early 19th century from the areas bordering the north of colonial Bengal as a landscape created for the British to recuperate and conserve their Saxon energy and race. The mapping of this newly acquired territory also involved the auxiliary scientific activity of ethnographically profiling the native population.’

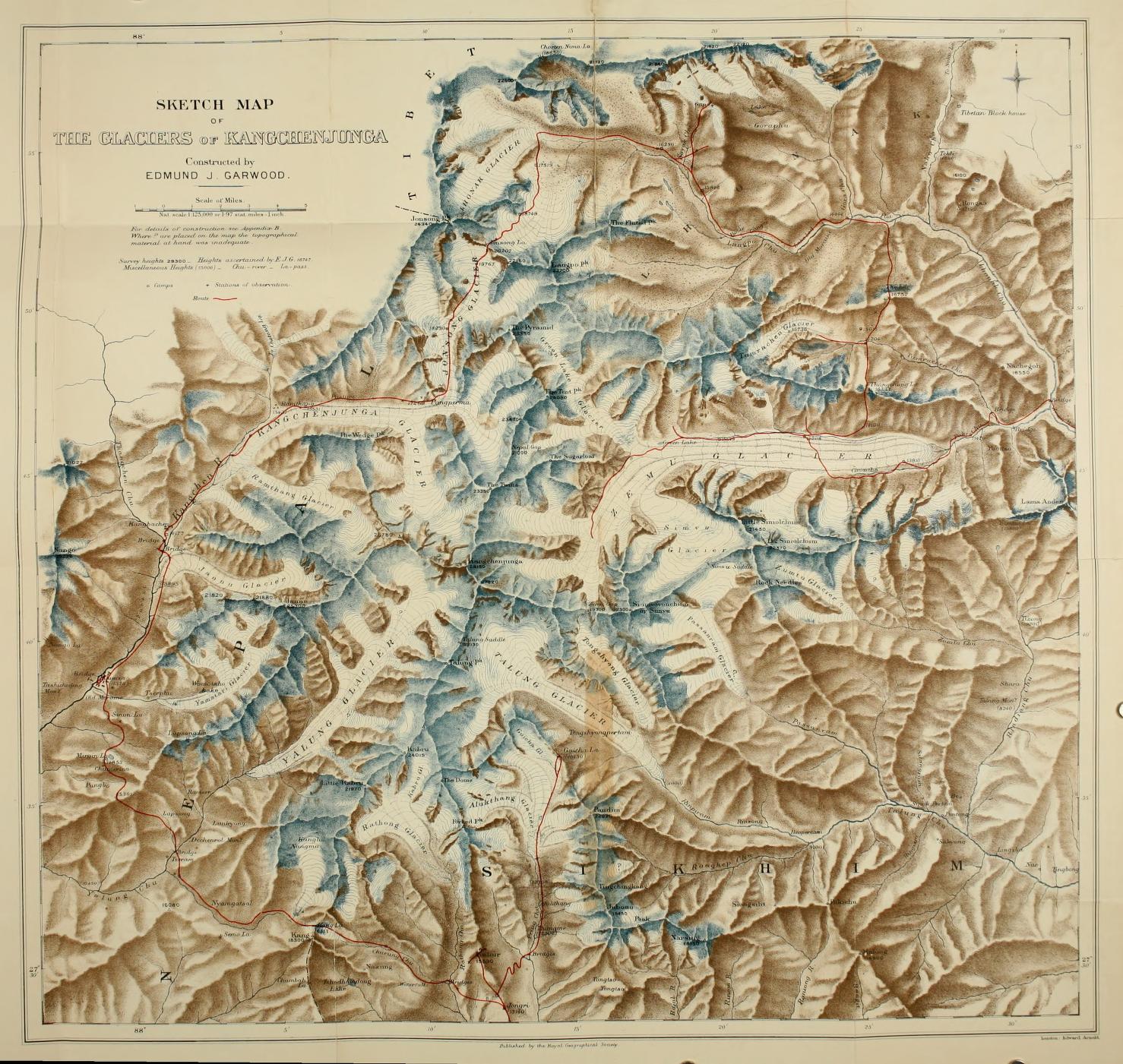

Sketch map of the glaciers of Kanchenjungha, from Douglas Freshfield's Round Kangchenjunga; a narrative of mountain travel and exploration (1903). Image courtesy: archive.org

The sciences of Flora and Fauna

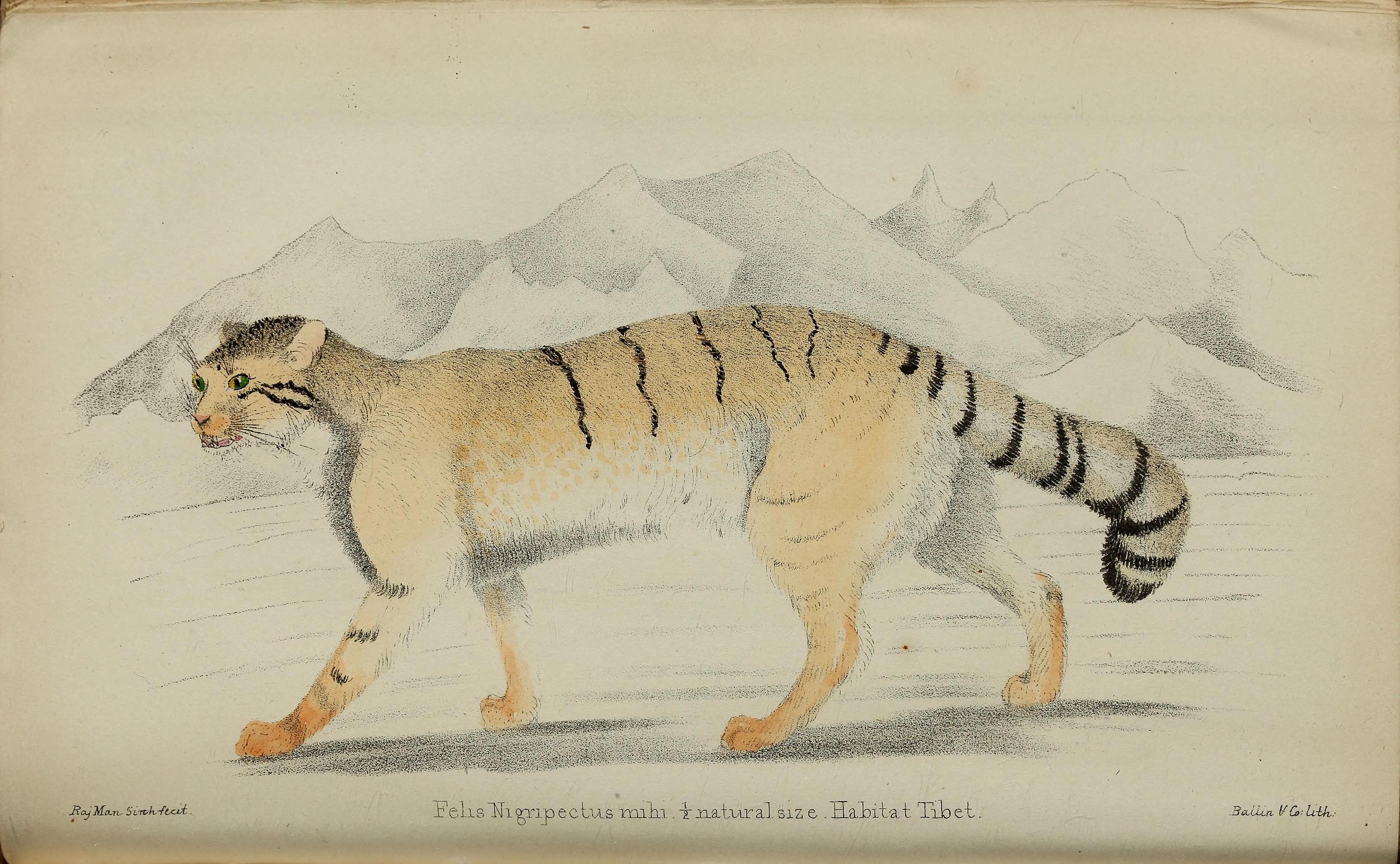

Brian Houghton Hodgson (1801-1894) was a British colonial administrator and scholar who worked for the British East India Company in Nepal from 1820 to 1843. After leaving the Company’s employment, he continued his scholarly work in Sikkim until 1858. Hodgson was one of the first European scholars of Buddhism and made significant contributions to the study of Buddhism and Himalayan fauna. Hodgson's work in Darjeeling contributed significantly to the field of zoology. He spent over 20 years researching the fauna of Nepal and Darjeeling and produced thousands of pages of notes and drawings detailing many species new to European science. Although his intended work on Himalayan animals, Zoology of Nipal, was never published, his drawings and notes are held by the Zoological Society of London. Hodgson is said to have commissioned thousands of drawings of birds and mammals from Nepalese artists.

Raj Man Singh, Felis nigripectus (Otocolobus manul nigripectus), from Hodgson, B.H. 1842. ‘Notice of the Mammals of Tibet, with Descriptions and Plates of some new Species’, Journal of the Asiatic Society of Bengal 11(1): 275–289. Image courtesy: Wikimedia Commons

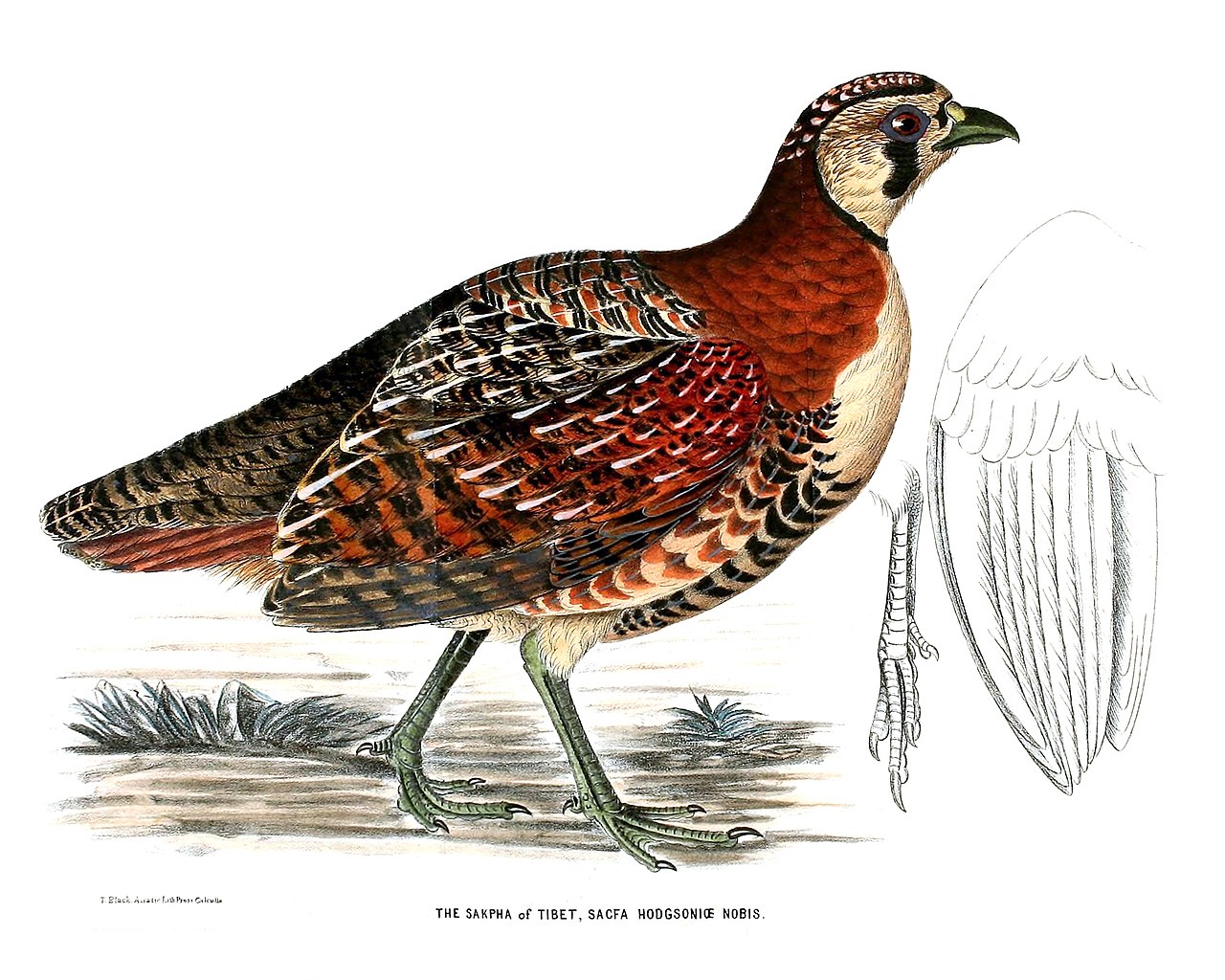

Raj Man Singh (attributed), lithography by T. Black, Perdix hodgsoniae, Journal of the Asiatic Society of Bengal, 1856. Image courtesy: Wikimedia Commons

According to the British natural History Museum, ‘These artists were trained by Hodgson to paint in the style required for scientific illustration. The drawings accurately depict the natural colours and external anatomy required for scientific identification. Hodgson frequently dissected his specimens to show the skeletal and other anatomical features, and encouraged artists to sketch these extra details on the drawings.' Raj Man Singh (Chitrakar) was one of the Nepalese artists employed by Hodgson.

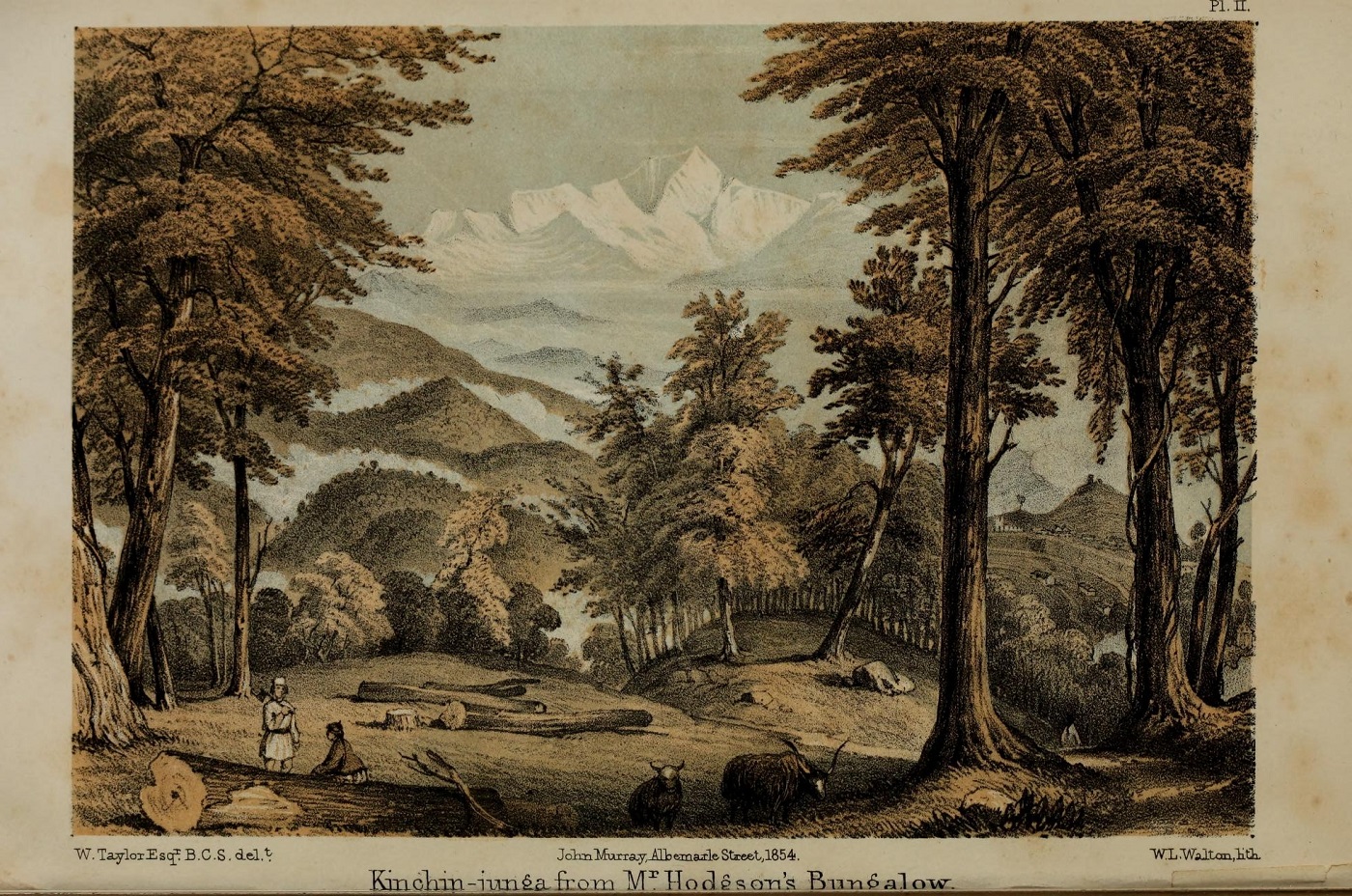

W. Taylor, View of Kanchanjunga from Hodgson's Bungalow, 1854, from J. D. Hooker's Himalayan journals; or, Notes of a naturalist in Bengal, the Sikkim and Nepal Himalayas, the Khasia Mountains, &c. Volume 1. Image Courtesy: Wikimedia Commons

Joseph Dalton Hooker (1817—1911) was a British botanist and explorer who made significant contributions to the study of Himalayan flora. He was a close friend and colleague of Charles Darwin and was one of the first scientists to support Darwin's theory of evolution by natural selection. Hooker's work in Darjeeling began in 1848 when he was appointed as the assistant director of the Royal Botanic Garden, Calcutta (now Kolkata). He spent several years exploring the Himalayas and collecting plant specimens, many of which were new to science. Hooker's most significant contribution to the study of Himalayan flora was his monumental work, The Flora of British India, which he began in 1855 and continued to work on for over 20 years. The work was published in seven volumes and described over 20,000 species of plants found in India, Burma, and Ceylon.

|

W. H. Fitch and J. D. Hooker, et al. Rhododendron grande, from The rhododendrons of Sikkim-Himalaya. Image courtesy: Wikimedia Commons |

Hooker's work in Darjeeling also included collaborations with other scientists, including Brian Houghton Hodgson, with whom he explored the Himalayan frontier and collected specimens of animals and plants. Hooker's work in Darjeeling and the Himalayas helped to establish the region as an important center for botanical research and contributed significantly to the study of Himalayan flora. Hooker and Hodgson represent two of many such colonial-era explorers and naturalists who expanded our understanding of the natural environment of the eastern Himalayas, making Darjeeling a significant platform for such research.

|

W. H. Fitch, Vaccinium Salignum and Vaccinium Serpens, from llustrations of Himalayan plants, 1855. Image courtesy: Wikimedia Commons |

Edward Lear’s Darjeeling

Edward Lear (1812—1888), an English artist and writer, spent time in Darjeeling during his travels in India where he was invited by the Viceroy, Lord Northbrook. He was known for his nonsense poetry and limericks, which were popular in his time and continue to be enjoyed today. Lear's time in Darjeeling is reflected in his sketches and paintings of the area, which capture the beauty of the Himalayan landscape. Lear's work in India also included illustrations for books and travelogues, as well as portraits of local people. According to a source, ‘Henry Bruce (who became Lord Aberdare in 1873), commissioned Lear to paint "an Indian scene of his own choice" for him when he went out to India. Lear reached Darjeeling in January 1874, and sketched the scene on the spot. He began working it up in oils in 1875, despatching the finished painting to Wales in May 1877.’

Edward Lear, Kangchenjunga from Darjeeling, oil on canvas, 47.12 x 72 in., 1872. Image courtesy: Wikimedia Commons

The photographer on the roof of the world

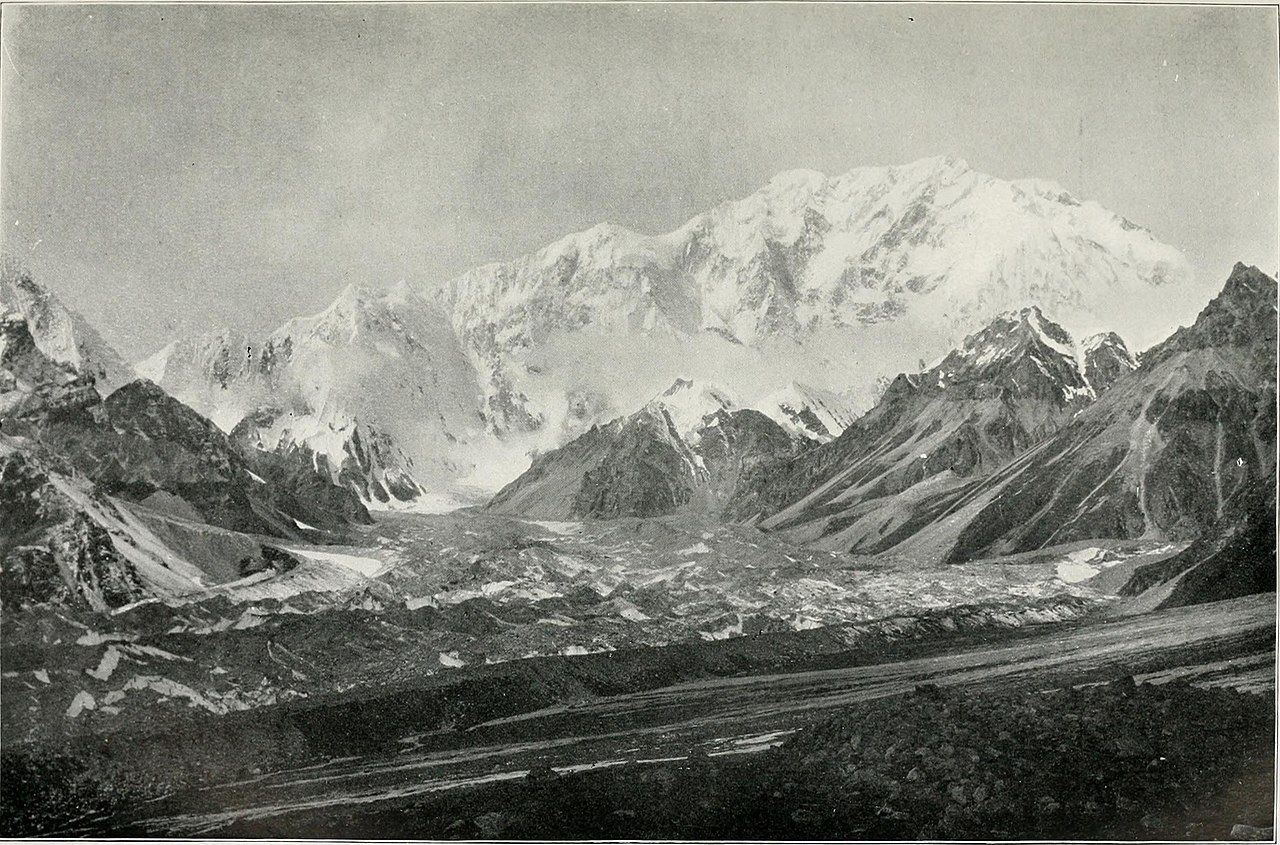

Vittorio Sella is one of the pioneering photographers of the Himalayas. He went with multiple parties, including Douglas Freshfield, a British mountaineer, explorer and geographer who led an expedition that circumnavigated the Kanchenjunga in 1899, and, later, with Prince Luigi Amdedeo di Savoia-Aosta, Duke of the Abruzzi. The latter’s royal purse allowed for a higher budget for documenting his ascents and Sella proved to be the best person for the job of photographing the majestic views.

Ed Douglas writes, ‘(Vittorio) Sella remains one of the very best mountain photographers in history, capturing images that recorded the architectural structure of the mountains but also something ineffable, something of their spiritual power. His photographs would inform and inspire generations of mountaineers to come.’

Vittorio Sella, Kanchenjunga from Green Lake Plain, from Douglas Freshfield's Round Kanchenjunga: a narrative of mountain travel and exploration. Image courtesy: Wikimedia Commons

Chronic Soddenness

Not everyone was impressed with Darjeeling’s location and its difficult terrain, however. In an irascible but witty account, Aleister Crowley, a British occultist who led the first attempt to climb Kanchenjunga (ending in disaster), wrote: ‘Darjeeling is a standing or rather steaming example of official ineptitude. Sir Joseph Hooker, one of the few men of brains who have explored these parts, made an extended survey of the district and recommended Chumbi as a hill station. ‘Oh well,’ they say, ‘Darjeeling is forty miles nearer than Chumbi. It will do rather better.’ So Darjeeling it was. The difference happens to be that Chumbi has a rainfall of some forty inches a year; Darjeeling some two hundred odd. The town is perched on so steep a ridge that there is practically no level road anywhere and one gets from one house to another by staircases as steep as ladders…. Almost the whole time I was there I was suffering from sore throat, arthritis, every plague that pertains to chronic soddenness. Do I like Darjeeling? I do not!’

Crowley’s description of the damp Darjeeling weather is significant, even though Indian artists were representing this ‘soddenness’ through their own pictorial innovations, especially Abanindranath and Gaganendranath Tagore. They employed their famous wash techniques to bestow a more melancholy mood on their painted scenes. While Abanindranath also made several expressive and personal views of Darjeeling town in his postcards, focusing on abstract views of marketspaces and its people, his washes featured finely observed traces of human intervention (and the advancement of technologies) on rugged ground, with one image figuring the ineffable tracks made on the mountains by the early railways. Gaganendranath’s work suggests the presence of Darjeeling's iconic tea gardens with a delicate touch of green.

Abanindranath Tagore, Untitled (Darjeeling Market), wash and ink on postcard. Collection: DAG

Abanindranath Tagore, Darjeeling, Himalaya Railway, Water colour, 7 x 10 in. Image courtesy: Google art and culture and Victoria Memorial Hall

Gaganendranath Tagore, Tea garden near Darjeeling, Water colour, 16.7 x 23.8 cm. Image courtesy: Google arts and culture and Victoria Memorial Hall

Gaganendranath Tagore also painted views of Kurseong, a neighbouring hill town that was included in the territories ceded to the British. An independent municipality was established there in 1879, by which time the Darjeeling hills had become more populated with residents from British India, along with a growing (and migrating) local Lepcha population.

Radha Charan Bagchi, Darjeeling, Oil on canvas, 1957, 19.7 x 23.5 in. Collection: DAG

Aside from the Tagores many artists from Bengal painted the views around Darjeeling. Radha Charan Bagchi (1910—1977) was one of the artists attempting to find a synthesis between academic realism and the Bengal School’s aesthetic of washed views. Darjeeling provides a perfect site for such visual experimentation as he captures the rolling hills shrouded in mist. He offers a view most travellers can witness as they make their way uphill on the road to Darjeeling, suggesting its increasing importance in a post-independent era for middle-class tourists from the plains.

Kisory Roy, Untitled (Darjeeling by Night), Oil on canvas, 1947, 18.0 x 24.0 in. Collection: DAG

Another significant academic naturalist of his time was Kisory Roy (1911—1965), who made several landscape studies across his career. His striking view of Darjeeling by night responded to the more general views of painting or photographing the hill station with objectives of achieving a clear sight of its features and people—an ethnographic eye that demanded documentary detail (of people, flora and fauna, along with mountain-scapes)—over the creation of a personal subjectivity. In Roy’s painting we see an individual ‘surrounded by trees at night-time with skies softly glowing in the moonlight’. Roy’s work also tells us about the growing number of residents on the hills which accounts for new sources of light and shade in an already visually rich environment.

Filming the Hills

As the growing demands of middle-class tourism reshaped the Darjeeling hills in the popular imagination, filmmakers were increasingly taking note of the location, attempting to invoke its rich history of contestation, appropriation and visual experimentation. Teeming with tea gardens, colonial décor, heritage eateries and the ‘toy train’ pulling into the highest railway station in the country, Darjeeling was fast becoming a potential museum for the postcolonial tourist. Transmuting these histories into metaphorical explorations of mood, character and place for the modern Indian subject, filmmakers from Bombay’s growing film industry headed for the hills as early as 1949 when Raj Kapoor filmed a few scenes for Barsaat (1949) there. Nasir Hussain’s Jab Pyaar Kisi Se Hota Hai (When Love Strikes, 1961) was another popular film that featured views of the famous hill station.

|

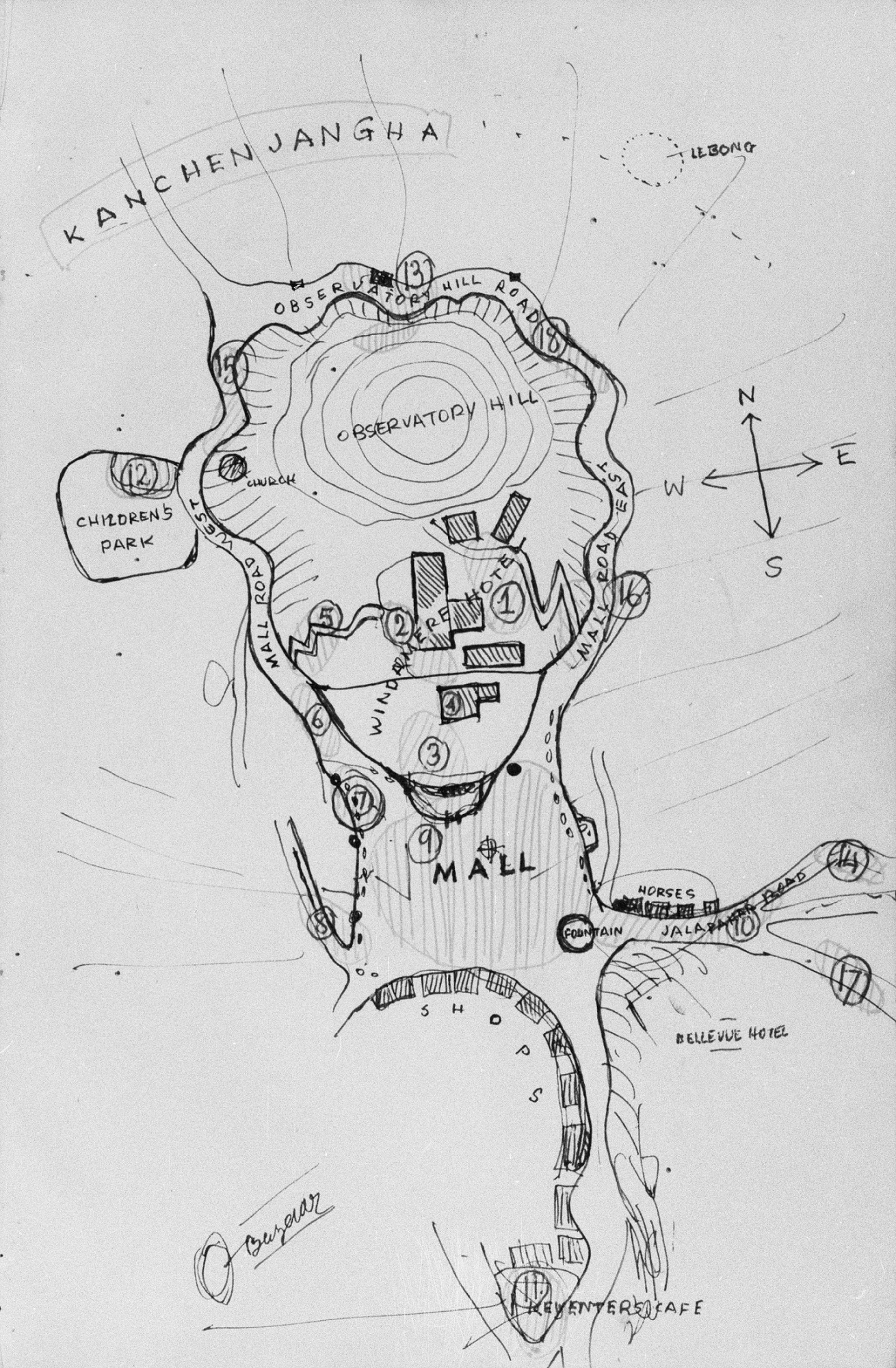

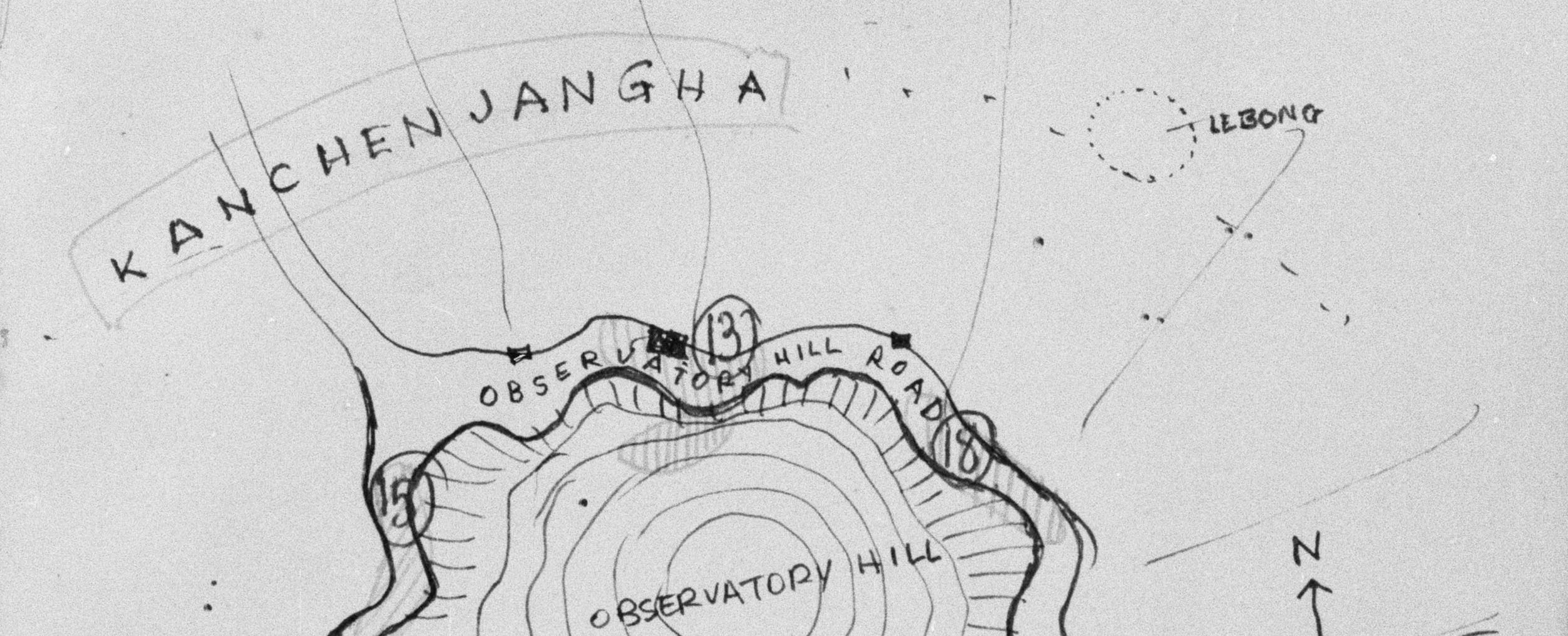

Satyajit Ray's Kanchenjunga Map, inkjet print on archival paper, 30.4 x 20.3 cm., 2012, from the Nemai Ghosh collection, DAG |

However, in 1962, Satyajit Ray released a film titled Kanchenjunga, exploring the mysterious significance of the mountain through the lives of an upper middle class Bengali family visiting Darjeeling from Calcutta (now Kolkata). It was Ray’s first original screenplay and his first film in colour. Why did he choose to film this particular film in colour? Ray told his biographer Andrew Robinson: ‘The idea was to have the film starting with sunlight. Then clouds coming, then mist rising, and then mist disappearing, the cloud disappearing, and then the sun shining on the snow-peaks. There is an independent progression to Nature itself, and the story reflects this.’ The heritage of the picturesque site in Darjeeling, its diverse natural environment and the inter-play of light and shade at different times of the day (the events of the film take place over a few hours in the same day) made it essential for Kanchenjunga to be filmed in colour.

Ray's title design for the film. Image courtesy: Wikimedia Commons

As the characters drift around Darjeeling town like a musical score, making secret forays, encountering layered conflicts within themselves in contrast to the innocence of the local people—signified by a song sung by a child—Ray employs and complicates several colonial stereotypes about Darjeeling and its associate in constructing the picturesque aesthetic: Kanchenjunga. One of the characters, played by the actor Pahari Sanyal, is a birdwatcher, expressing concerns about the dwindling numbers of birds in the hills and speculating how the nuclear age might spell doom for them. His presence references a number of similar nature enthusiasts stretching right back to the days of Hooker and Hodgson during the colonial period.

Satyajit Ray's Kanchenjunga Map (detail), inkjet print on archival paper, 30.4 x 20.3 cm., 2012, from the Nemai Ghosh collection, DAG

The film was a bold experiment and somewhat of an oddity in Ray’s oeuvre—perhaps especially due to its vision of ennui afflicting the Bengali middle-class tourists in what was supposed to be an exotic locale. It was not commercially successful but the filmmaker’s attachment to the project remained unscathed even years later when he said, ‘Kanchenjungha told the story of several groups of characters and it went back and forth… but it wasn’t liked. The reaction was stupid. Even the reviews were not interesting. But, looking back now, I find that it is a very interesting film.’

Featuring his legendary hands-on work on every aspect of the film’s production, Ray sketched a map of the town highlighting the movements of his characters and the spot from where the great mountain would be viewed. According to the plot of the film, the desire to see a glimpse of Kanchenjunga drives the characters led by the family patriarch Indranath (played by Chhabi Biswas). However, it remains shrouded in mist throughout—and by the time it clears up and offers the audience the much-awaited view, the characters have lost all interest in it, becoming preoccupied once again by their own internecine troubles. Thus, the film climaxes with a view of Kanchenjunga, the crowning view for the queen of the hills, Darjeeling.