'Don't Sit Idol': Exploring Patuapara and Kalighat Art

'Don't Sit Idol': Exploring Patuapara and Kalighat Art

'Don't Sit Idol': Exploring Patuapara and Kalighat Art

collection stories

'Don't Sit Idol': Exploring Patuapara and Kalighat ArtKalighat is one of the oldest and culturally significant neighbourhoods in South Kolkata, with a history deeply intertwined with the formation and growth of the city itself. The area is primarily known for the revered Kali Temple, whose origins trace back to fifteenth-century texts, although the present temple structure was built in 1809 under the patronage of the Sabarna Roy Choudhury family, who also provided extensive land grants to sustain the temple rituals. Besides its central importance as a place of pilgrimage, the neighbourhood gave rise to some of the most enduring urban art forms in the city, as painters (or 'patuas') attempted to carve out a livelihood from selling popular images of gods and sacred narratives, and increasingly, more secular commentaries on the profane life of the colonial city. |

Louis Buvelot

The Kalighat Kali Temple on the Hoogly, Calcutta (detail)

1855, Watercolour on paper, 9.5 x 12.2 in.

Collection: DAG

|

Historically, Kalighat was part of the thirty-three villages collectively known as Dihi Panchannagram, which fell under the jurisdiction of the East India Company after the mid-eighteenth century and was considered a suburban area beyond the old city boundary marked by the Maratha Ditch. Although this has been contested, the name ‘Kalighat’ itself is believed to be a source for the original name of Kolkata (Calcutta), demonstrating the area's foundational significance to the city's identity. |

|

|

Unidentified Artist (Early Bengal School)

Raj Rajeshwari

Middle to late 19th century, Oil on canvas, 30.0 x 26.2 in.

Collection: DAG

Johnston and Hoffmann

Goddess Kali at Kalighat temple, Calcutta

Collection: DAG

Culturally, Kalighat evolved as a vibrant site of religious and popular artistic expressions. The temple precinct attracted artisans such as scroll painters and idol makers, notably in the adjacent neighbourhood of Patuapara, where families transitioned from traditional patachitra painting to idol-making in the twentieth and twenty-first centuries, although some artists have retained their longstanding practice of scroll painting, incorporating new subjects, styles and patrons. This neighbourhood served as a hub for pilgrims and cultural productions centred around the goddess Kali, linking religious practices with local livelihoods and arts, such as the famous Kalighat painting style, which emerged as a nationalist artistic idiom resisting colonial dominance in nineteenth and twentieth century Bengal. |

F. B. Solvyns

Busso Djeng (A folio from Les Hindous, ou Description de leurs moeurs, coutumes er ceremonies)

1808, Colour etching on paper, Print size 13.7 x 19.5 in.

Collection: DAG

Prince Alexis Soltykoff

Procession de la Déesse Kali (Procession of the Goddess Kali)

1841, Lithograph on paper, 19.5 × 27.2 in.

Collection: DAG

However, its anti-colonial reputation in the colonial city of Calcutta was not a simple one. As the scholar Deonnie Moodie put it in a conversation for the DAG Journal: ‘Kalighat, despite its significance as a prominent temple in Calcutta, was often reviled by Hindu reformers. It embodied everything they sought to reform: polytheism, iconoclasm, and unrefined forms of worship. The temple's depiction of the goddess Kali with her elongated tongue, holding severed heads, and adorned with skulls epitomized a form of worship that clashed with the sanitised versions propagated by reformers.' ‘Daily animal sacrifices, still practiced at Kalighat, further fuelled its notoriety among reformers and colonial administrators alike. Figures such as Vivekananda, despite being raised by a Shakta mother who frequented Kalighat, notably omitted any mention of the temple in their works—a silence that speaks volumes about societal perceptions.’ |

|

Despite its vilification, it was acknowledged as a potent site of power, a place where devotees sought miracles and interventions. This duality underscores a broader societal dichotomy: the powerful often exist outside the bounds of respectability, especially for those shaped by the prevalent bhadralok ethos. |

|

|

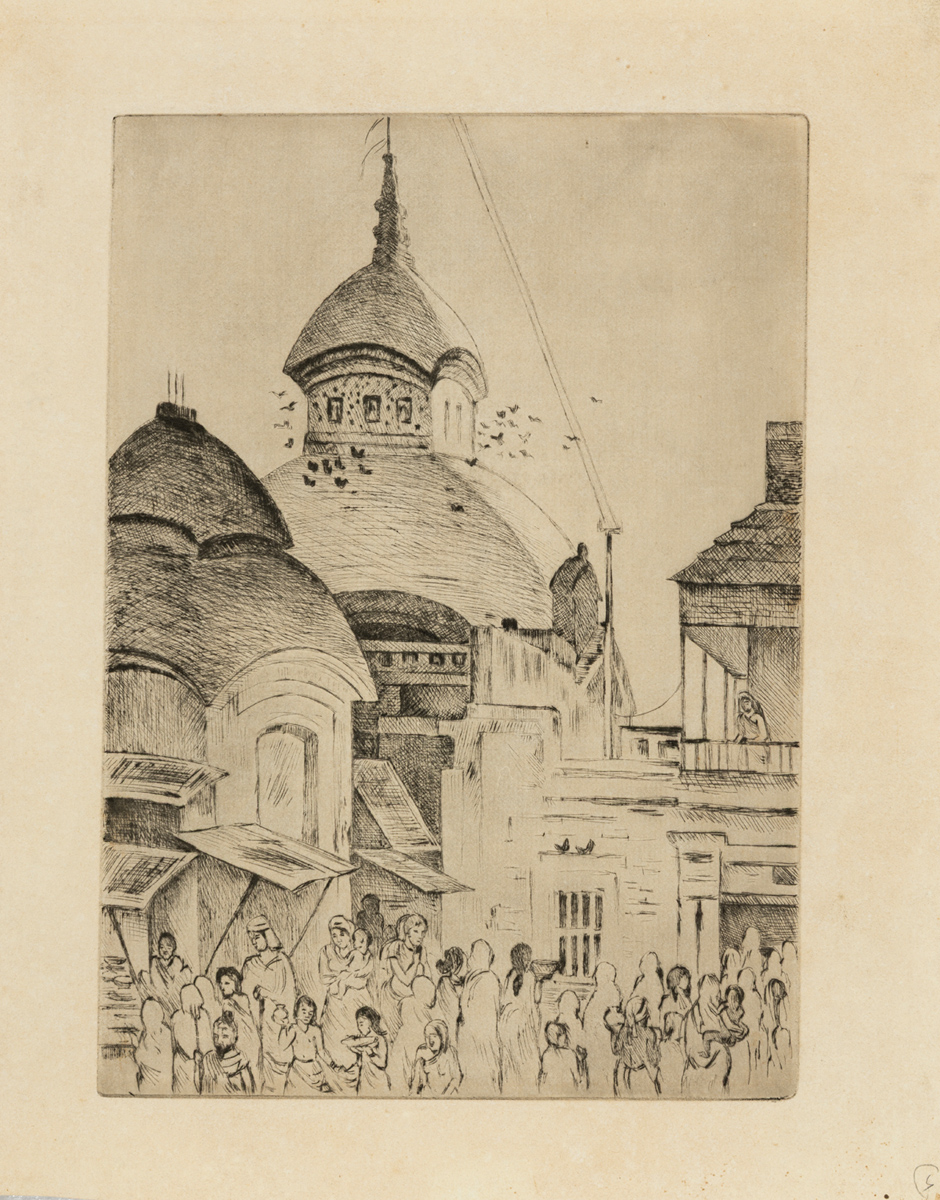

Ramendranath Chakravorty

Temple of Kalighat

1936, 9.0 x 6.5 in.

Collection: DAG

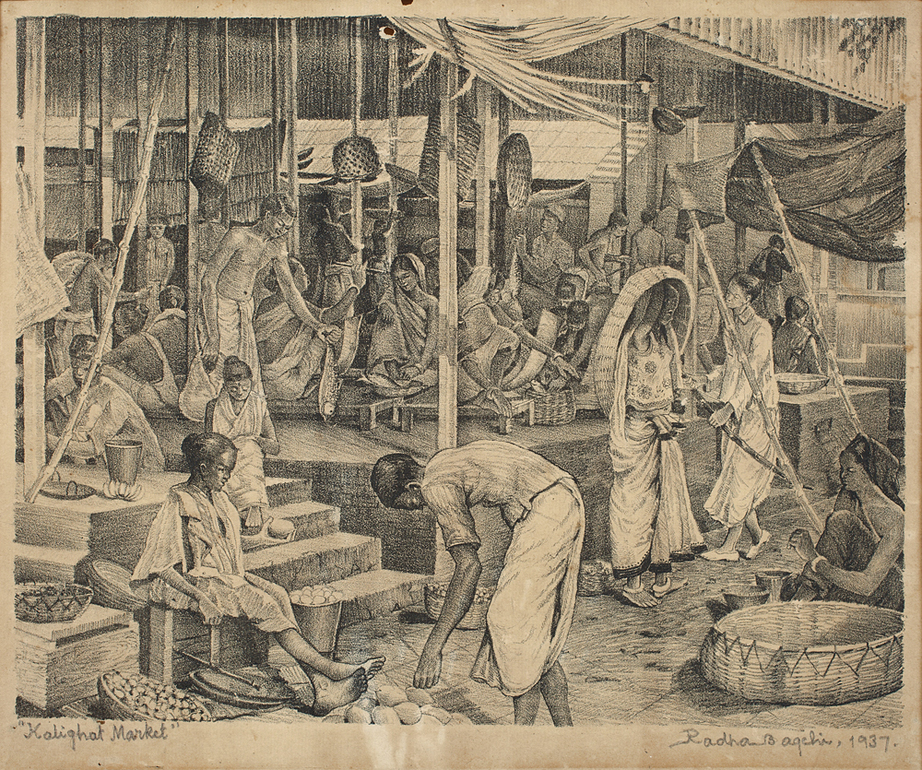

Radha Charan Bagchi

Kalighat Market

1937, Lithograph on paper, 9.2 x 11.7 in.

Collection: DAG

The neighbourhood’s history is marked by the layering of social and political changes, including British colonial administration and the assertion of indigenous religious authority, which played out through temple administration and urban transformations. The Kalighat temple complex also features other significant temples, such as the Shyam Rai Temple, built in the nineteenth century, indicating a pluriform religious landscape. The area's dense population and colonial-era modernisation efforts brought about conflicts, and resistance among different class groups, making Kalighat a crucial locale for understanding modern Kolkata's socio-cultural evolution. |

Louis Buvelot

The Kalighat Kali Temple on the Hoogly, Calcutta

1855, Watercolour on paper, 9.5 x 12.2 in.

Collection: DAG

Unidentified Artist

Balarama, Subhadra and Jagannath

Watercolour over lithographed outlines, highlighted with silver pigment on paper, pasted on paper, 15.7 x 11.0 in.

Collection: DAG

Scholars of Urban Planning and Architecture, such as Mainak Ghosh, have examined the urban transformation of Patuapara, the artists’ colony in Kalighat, through the lens of declining traditional folk art communities. Focusing on Kalighat pat painting—born from rural patuas migrating to sell scrolls to temple pilgrims in the nineteenth century—his study maps how technological shifts to cheap prints eroded economic viability, forcing artists into idol-making. A three-step methodology analyses physical settings (linkage structures, urban elements), community dynamics (surname shifts from Chitrakar to Pal, loss of communal spaces like the Baroyari Shitala temple), and their interplay, revealing a diminished ‘sense of community’ amid globalisation and new economic transformations that have affected the production of work. |

|

'The distinctive urban pattern of Patuapara is irregular in its geometry. It consists of narrow, winding alleys with temporary artist workshops on one side or residential units on both sides and building heights ranging from 9.8-23.0 ft. (3-7 m). Along these narrow lanes are some breakout spaces, usually in the form of congregational areas (primarily used during festivals) or religious buildings. The plots and buildings are varying sizes and shapes; thus, the whole area has a coarse grain with an uneven texture.' 'Traditional Folk Art Community and Urban Transformation: The Case of the Artists' Village at Kalighat, India' (Ghosh and Banerjee 2019) |

|

|

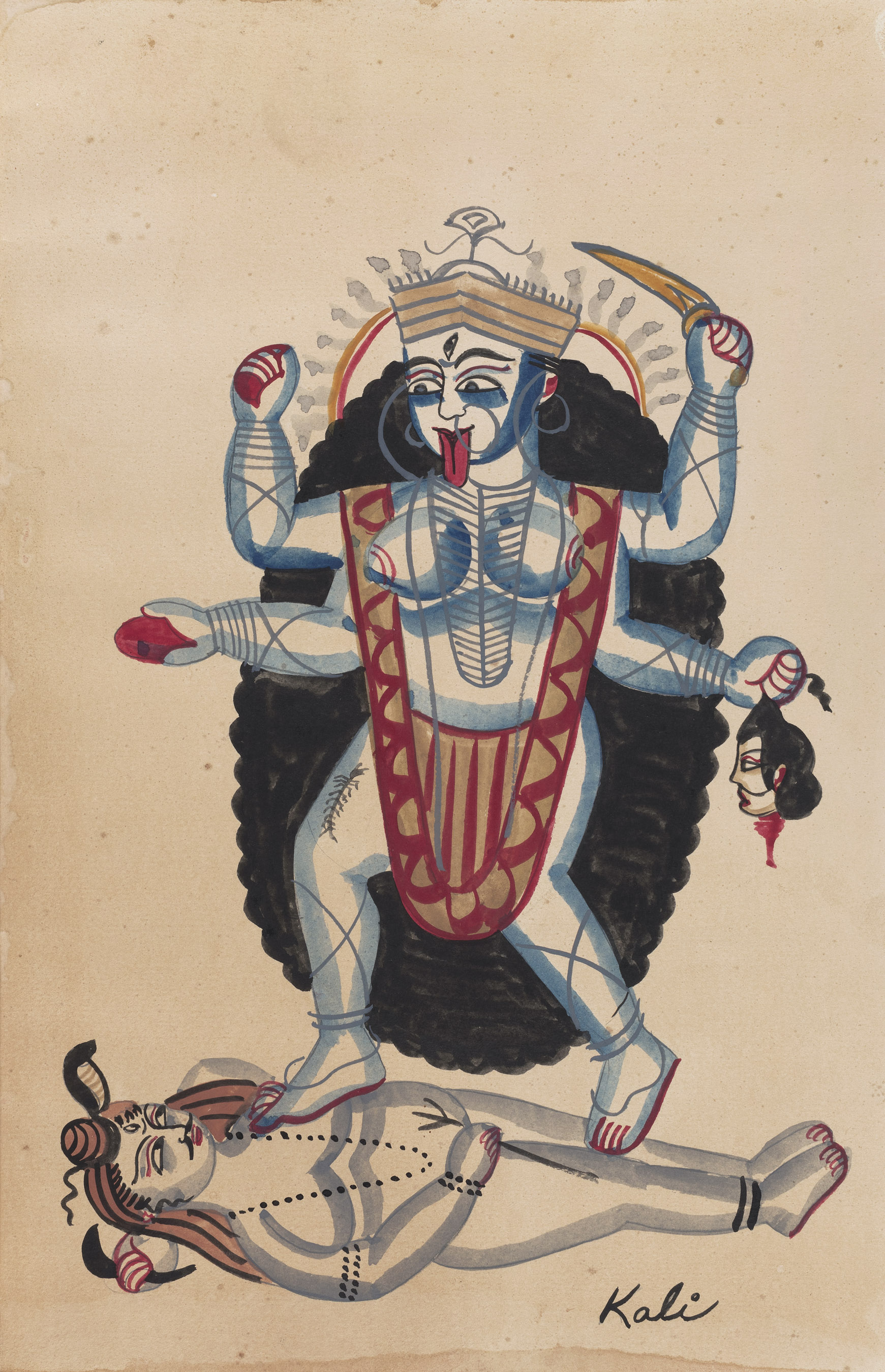

Unidentified Artist (Kalighat Pat)

The Ten Avatars of Kali (series)

c. 1880-1920, Watercolour on paper, 11.7 x 7.2 in.

Collection: DAG

Bhaskar Chitrakar, a Kolkata-based artist from the historic Patuapara neighbourhood in Kalighat, is one of the last active descendants of the Kalighat patachitra tradition. Bhaskar continues this legacy by blending traditional techniques—such as using natural powder pigments and hand-ground colours—with contemporary themes and social commentary. His art humorously and critically reinterprets classic Kalighat subjects, portraying iconic gods and goddesses in modern contexts and engaging with current social themes like the ‘Babu-Bibi’ lifestyle or pandemics. |

Unidentified Artist (Kalighat Pat)

The Ten Avatars of Kali (series)

c. 1880-1920, Watercolour on paper, 11.7 x 7.2 in.

Collection: DAG

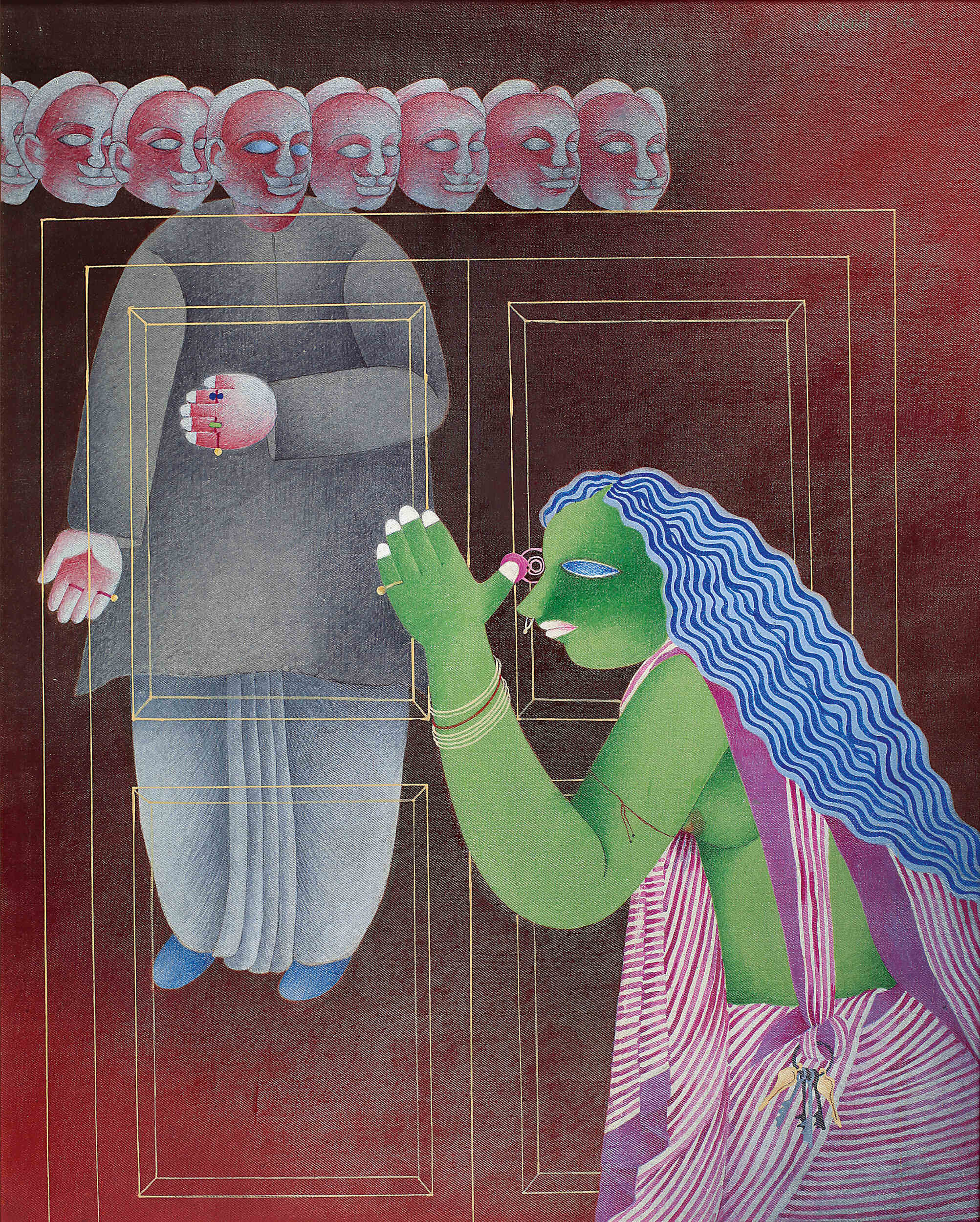

Dharamnarayan Dasgupta

Untitled

Tempera on canvas, 27.5 x 22.0 in.

Collection: DAG

Bhaskar Chitrakar at work

From Sourav Guha's Nagar Patua

Screengrab from YouTube

Unlike the fading industry of his forebears, Bhaskar's work is commercially viable, showcased in galleries and international folk art markets. He paints primarily on commission, engaging urban folk culture in a dynamic, evolving idiom that sustains Kalighat's artistic heritage while renewing its relevance today. Although he works out of his Patuapara studios, the Kalighat art-form is now a ubiquitous presence in Bengal and has been adopted by various artists beyond Kalighat, including fellow urban modernists such as K. C. Pyne or Dharamnarayan Dasgupta, as they draw on the form’s reputation for mingling humour, criticism and spontaneity. Bhaskar’s own inspirations spread across the world to include figures like Frida Kahlo, whom he has depicted as a muse in his continuing dialogue between tradition and modernity. |

|

Unidentified Photographer Bathing at Kalighat, Calcutta Undated, Albumen print on paper, 8.0 x 11.1 in. Collection: DAG |