Patronage, Pedagogy and Exhibition: Early History of the Jeypore School of ArtShaon Basu October 01, 2024 The ‘Jeypore School of Industrial Arts’ opened in 1866 at the behest of the Maharaja Ram Singh II. The Maharaja brought the P. W. D. to Jaipur in 1860 as part of his larger vision of ‘modernizing’ the city, and the school of art was a part of this project. What were the objectives of the patrons and how were they attained in tandem with colonial administrators? The curious trajectory of this school illustrates a case of collaboration, in service of Indian craft traditions. |

Unidentified photographer

The Albert Hall & Museum, Jaipur

Silver albumen print on paper, late 19th century, 7.2 x 9.2 in. / 18.3 x 23.3 cm.

Collection: DAG Archives

|

|

Jaipur School of Art produced pottery, after pupil Bhola

Earthenware jar and cover, Fritware with underglaze decoration

c. 1880, 29.2 x 25.4 cm.

Collection: Victoria & Albert Museum

In the latter half of the nineteenth century, art schools began to emerge across the Indian subcontinent as thriving centers of research and systematic inquiry into traditional Indian handicrafts and community-based hereditary models of craft production. But the schools also became a vibrant space for experimenting with the new pedagogical models as western academicism encountered pre-existing communities of artisans’ workshops. Peculiarly enough, the institutions were called ‘schools of industrial arts’ in their inaugural years, indicative of the intention behind opening the schools, and provided new generations of craftsmen with the best possible learning environment. The faculties comprising predominantly of British teachers instituted a suitable model of education combining academic training with native techniques to scale up the production as the outputs from the schools’ workshops went to meet the demands of the European market, following the successful reception of Indian art in the Great Exhibition in London in 1851. |

|

|

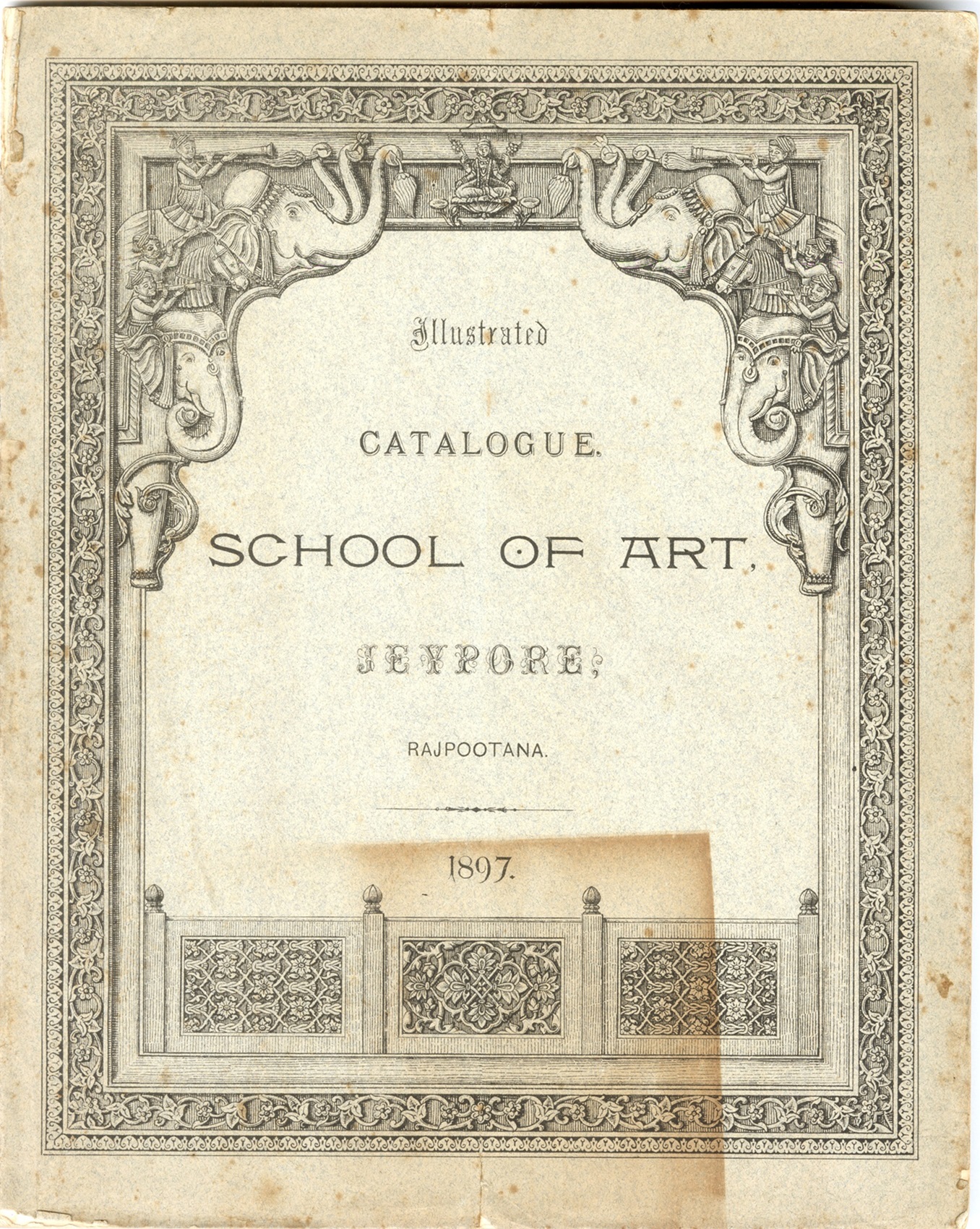

Cover page

Illustrated Catalogue School of Art, Jeypore, Rajpootana

Printed book, 1897 (published), Closed size: 12.2 x 10 x 0.2 in. / 31 x 25.4 x 0.5 cm, Open size: 12.2 x 19.6 x 0.1 in. / 31 x 49.8 x 0.3 cm.

Collection: DAG Archives

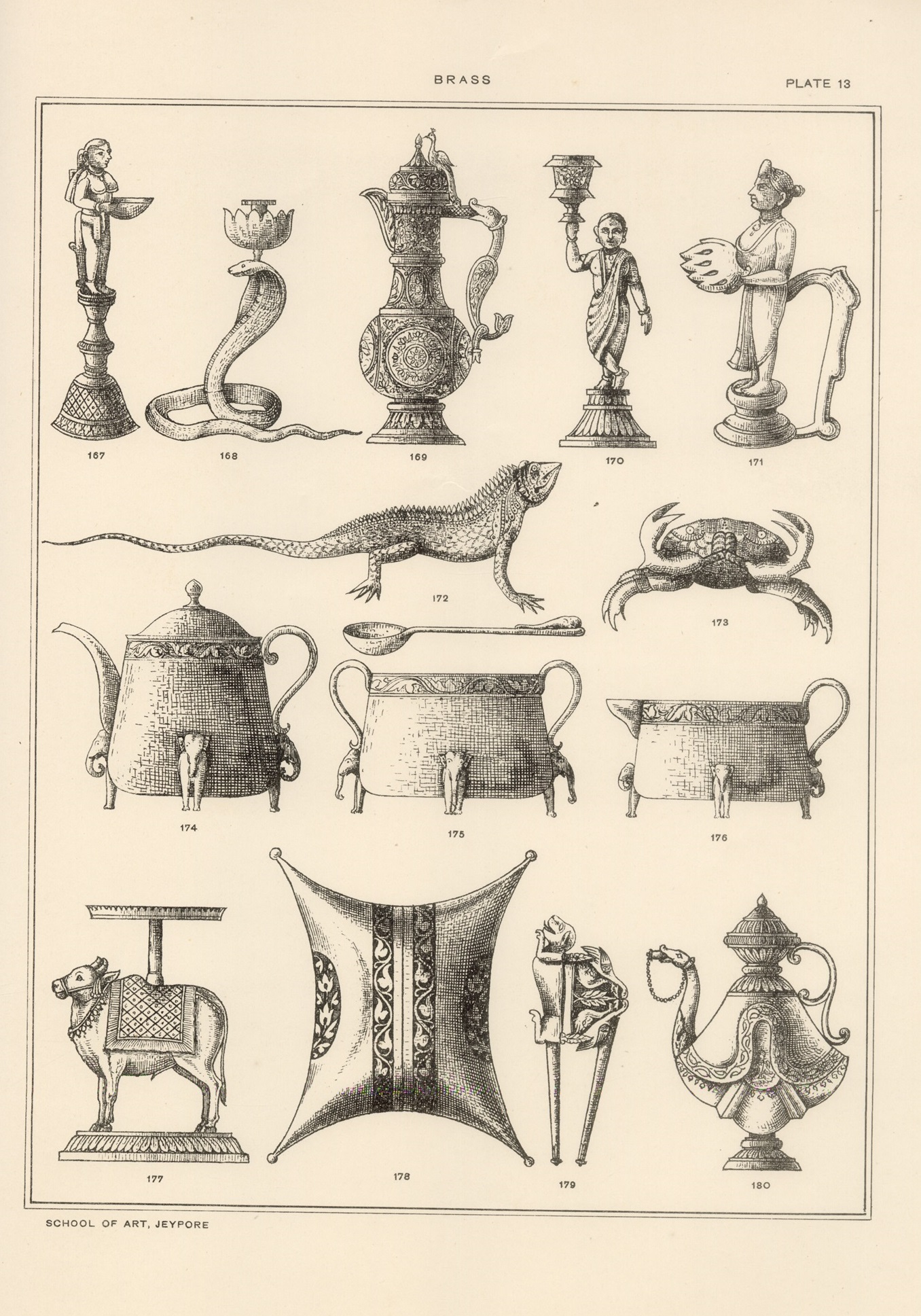

Illustrations of brassware

Illustrated Catalogue School of Art, Jeypore, Rajpootana

Printed book, 1897 (published), Closed size: 12.2 x 10 x 0.2 in. / 31 x 25.4 x 0.5 cm, Open size: 12.2 x 19.6 x 0.1 in. / 31 x 49.8 x 0.3 cm.

Collection: DAG Archives

The ‘Jeypore School of Industrial Arts’ opened in 1866 at the behest of the Maharaja Ram Singh II. The Maharaja brought P. W. D. to Jaipur in 1860 as part of his larger vision of ‘modernizing’ the city, and the school of art was a part of this project. The darbar of Jaipur felt that the teaching modules followed in the art schools of Madras, Calcutta and Bombay were too European since they laid so much emphasis on drawing instructions. The European influence was percolating in the product designs. The darbar instead ‘wished rather to promote the technical and industrial arts of more local origin … offering ‘a sound practical education in industrial arts’ to boys from the hereditary artisan castes to enable them to achieve employment,’ as art historian Giles Tillotson noted in his essay Jaipur Exhibition of 1883. Despite the darbar’s reluctance, drawing was still mandatory for students, especially the practice of drawing ‘from nature’. For instance, when this skill was applied in the pottery workshops, the results were astonishing, producing scenes of animals in the glazed jars and vases that were hot favourites among the tourists. |

|

|

Shield dhal watered steel with decorative borders in gold kuftkari and figurative designs in gold

Patiala, c. 1850

Diameter: 39.4 cm.

Collection: Victoria & Albert Museum

Shield dhal watered steel with decorative borders in gold kuftkari and figurative designs in gold (detail)

Patiala, c. 1850

Diameter: 39.4 cm.

Collection: Victoria & Albert Museum

The School’s first director Dr. de Fabeck, and Jaipur P. W. D.’s director Swinton Jacob worked closely in designing extraordinary buildings across the city in the ‘Indo-Saracenic’ style, best instantiated by the Mayo hospital, an eclectic blend of Victorian Gothic and Indian ornamental motifs. From the outset, the school’s main ideology was to ‘exhibit’ rather than to produce articles of direct utility. In the early years, a catalogue of outline drawings of household items like pottery, enamel and brass, as well as wood carvings, furniture and damascene works (koftgari) was published by the school for commercial purpose, with a list of their dimensions and price. Dying crafts like koftgari and tarkashi, which required fine craftmanship and a heredity-based knowledge, were revived in the school workshops. The Albert Hall Museum in Jaipur still exhibits a regal panoply of arms and armors, swords, shields, and daggers, with richly embellished hilts, handles and scabbards that showcase the ostentatious pride of the Hindu warrior creed—the Rajputs. Examples of these crafts were difficult to find or acquire in the baazar, but highly sought after by the tourists, so the school supplied authentic specimens of the same crafted objects, soon turning their enterprise into a successful ‘tourist craft industry’. |

|

|

Jaipur School of Art produced pottery, after pupil Bhola

Earthenware jar and cover

Fritware with underglaze decoration, c. 1880 , 30.5 x 25.9 cm.

Collection: Victoria & Albert Museum

In the same year when the school was set up, the principal of the Madras School of Art, Alexander Hunter was invited by the Maharaja to survey the manufacturing units and advise on potential improvements. Upon arrival, Hunter found out that white glazed stoneware with blue patterns were still practiced in the old city, and he loved the glazed tiles of the Amber Fort. He also found deposits of gypsum or sulphate of lime in the outskirts of the city which are very useful materials for making moulds and models. Therefore, with available natural resources and skilled artisans around, the glazed pottery workshop was set up soon and produced excellent specimens that earned accolades in several exhibitions. In February 1876, many objects were displayed on the occasion of the Prince of Wales, Albert’s, visit. Four large vases were specially commissioned for the Governor General and Viceroy that fetched 6000 rupees. In the Jaipur exhibition of 1883, the first native director of the school, Opendranath Sen took much pride in introducing the blue pottery of Jaipur to the world. |

|

|

Unidentified photographer

The Albert Hall & Museum, Jaipur

Silver albumen print on paper, late 19th century, 7.2 x 9.2 in. / 18.3 x 23.3 cm.

Collection: DAG Archives

The Prince of Wales’ 1876 visit was serendipitous in many ways in modern Jaipur’s history as center of art and cultural patronage. A special building was already on the plan of the Maharaja as part of his dream of modernising the city, and to give a permanent home to the dazzling artefacts that were produced, and acquired. The Maharaja deemed it as the opportune moment, and Prince Albert laid the foundation stone for a special building dedicated to the arts that would cement Jaipur’s place as the cultural epicenter of Rajasthan. Although, the name ‘Albert Hall’ was decided on the foundation day in 1876—‘twinning’ Jaipur with London—the actual building gestated for eleven years and opened to the public in February 1887, since the Maharaja wanted it to be an architectural marvel. The museum still exists in all its glory—as a testament to the Maharaja’s vision, with poignant marble carvings on the walls. In architect Colonel Jacob’s words, ‘the endeavour has been to make the walls themselves a museum, by taking advantage of many of the beautiful designs in old buildings near Delhi and Agra and elsewhere.’ |

|

|

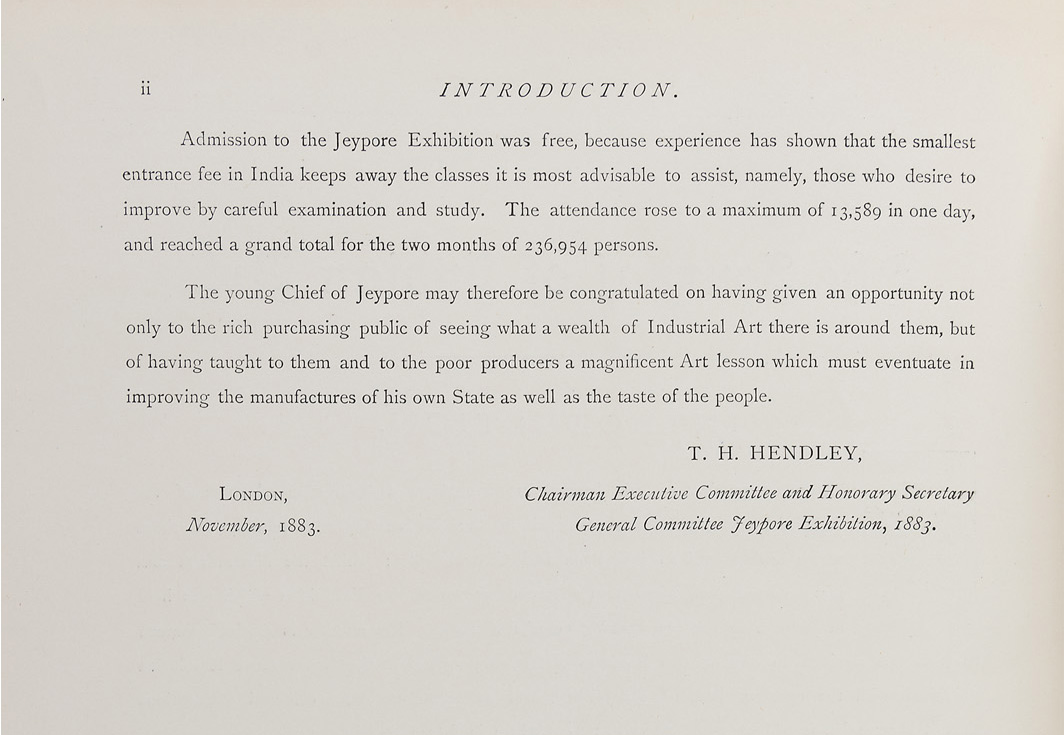

T. H. Hendley, Chairman Executive Committee and Honorary Secretary, General Committee Jeypore Exhibition, 1883

Closing paragraphs of the Introduction to the Special Issue on Jaipur Exhibition of 1883, Journal of Indian Art & Industry, Volume 1, Issue 2

Print on paper, 1884, 14.4 x 10.4 in. / 36.6 x 26.4 cm.

Collection: DAG Archives

The Jaipur exhibition of 1883 served as the precursor to the Albert Museum and many of the objects that we see there today had been first exhibited then. Thomas Holbein Hendley was appointed as the curator of this exhibition. Hendley’s acquisition spree for this grand show began in 1881 and was assisted by eminent personalities like General Alexander Cunningham, the founder of the Archaeological Survey of India and Caspar Purdon Clarke, an authority on contemporary Indian craftsmanship, as well as Pandit Braj Ballabh, a native head clerk, since it was difficult to infiltrate into the local baazars as European collectors. Hendley was also the founding editor of the ‘Journal of Indian Art and Industry’— the seventeen volumes of this journal still serve as an authoritative resource for research into the handicrafts across regions in the Indian subcontinent. |

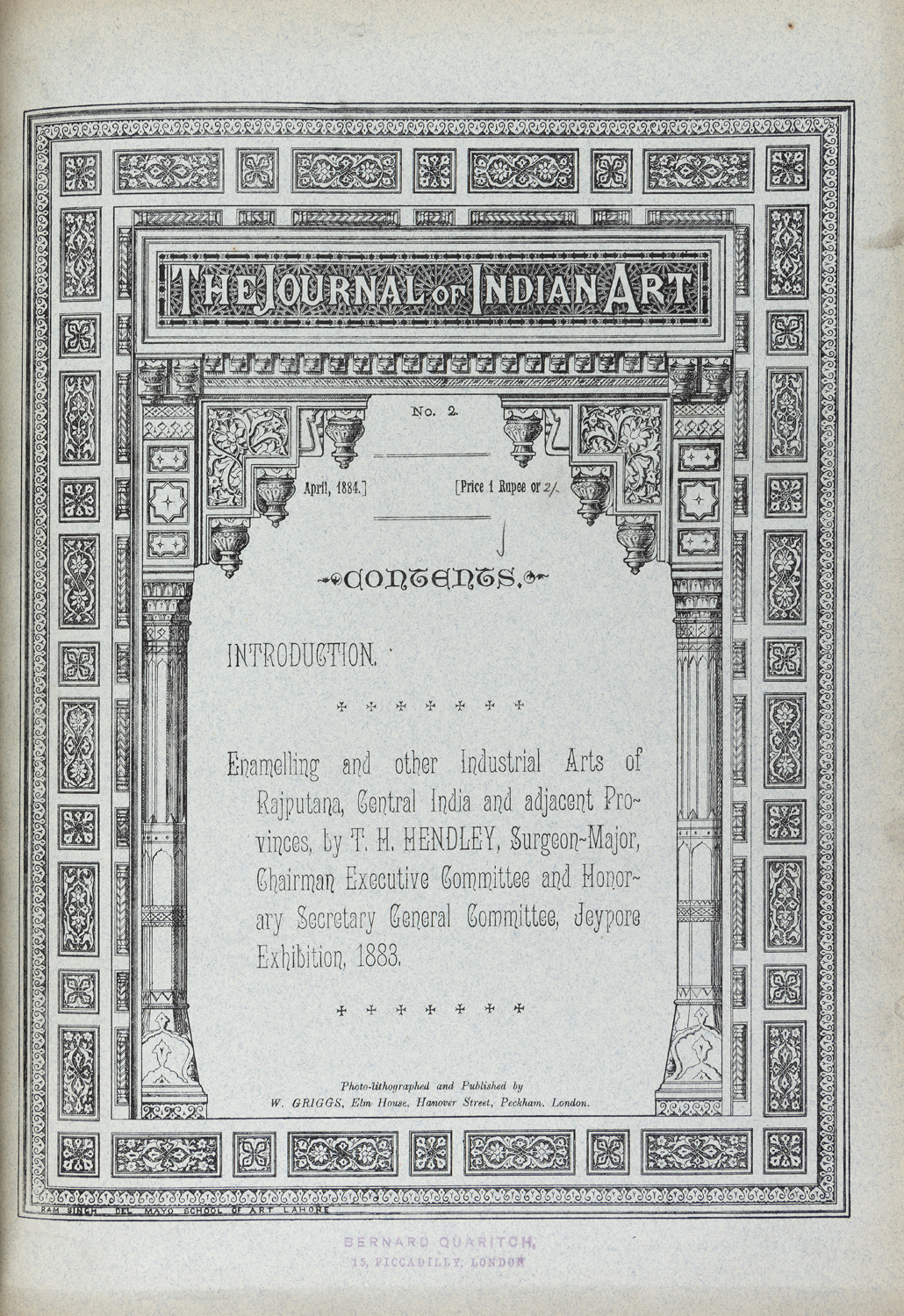

Drawn by Ram Baksh (illustrator), School of Art, Jeypore

Cover page of the issue

Journal of Indian Art & Industry Volume 1, Issue 2, Photolithograph on paper, 1884 (published) 14.4 x 10.4 in. / 36.6 x 26.4 cm

Collection: DAG Archives

Drawn by Ram Baksh (illustrator), School of Art, Jeypore

Illustrations of Designs for Modern Enamel

Journal of Indian Art & Industry Volume 1, Issue 2, Photolithograph on paper, 1884 (published) 14.4 x 10.4 in. / 36.6 x 26.4 cm

Collection: DAG Archives

The 'Journal of Indian Art and Industry’s' April issue of 1884—the second issue of the journal—was specially dedicated to the 1883 exhibition. Hendley took twelve years to prepare a sumptuous four-volume catalogue of the exhibition, Memorials of the Jeypore Exhibition. The Maharaja sponsored the publication and sent copies to museums, statesmen and libraries around the world as evidence of the cultural achievements of modern Jaipur. British photographers and students at the school of art led by their teacher Ram Baksh illustrated the volumes. The Times, London, reviewed the exhibition on 20 September 1883. Praising the Maharaja’s efforts, it commented that ‘[he] set an example which has produced a most excellent effect on popular opinion generally, both by encouraging Native Princes and Chiefs to exhibit their treasures and by inducing the labourers and artisans to inspect the improved methods and the highest forms of production in their different crafts and profession.’ |

|

|

Gopal Ghose

Udaipur 1933

Water color and graphite on paper, 1933 , 20.0 X 13.5 in. (50.8 X 34.3 cm)

Collection: DAG

Schools of art like the one at Jaipur challenged the consolidation of Western cultural hegemony, if only to suggest the existence of other powerful ideological forces at play. A close study of the institutions, aided by the archives, give us many (hi)stories about unprecedented and interesting collaborations between the British administrators and their native counterparts, allowing us to expand the scope of questions regarding the agency of the colonised. As Tillotson pointed out in his essay, ‘Whatever Jaipur’s Exhibition and Museum may tell us about Hendley and Jacob, they also have much to tell us about the Maharaja and his darbar as patrons, about the city’s arts administrators and artists as contributors, and about its public as audience.’ Many of the native students excelled in the arts reserved for the Europeans and dismissed the notion that the Indians were only good in certain mechanical skills. Native student Jai Chandra won an award in drawing and went off to work in Swinton Jacob’s office. Ram Baksh was appointed as the drawing teacher at the school. Conversely, the British administrators also invented pedagogical strategies to not deter but further nurture and improve what is true and universal in the arts of India. |