Witnessing the Famine: On the Bengal Painters' TestimonySoumava Das July 01, 2024 In 1944, an initiative was taken by the All India Students’ Federation (A. I. S. F.), just a year after the great Bengal Famine of 1943, to publish the reproductions of artworks in an album by Rabindranath Tagore, Abanindranath Tagore, Nandalal Bose, Jamini Roy, Ramkinkar Baij, Mukul Dey, Paritosh Sen, Zainul Abedin, Deviprasad Roy Chowdhury and Chittaprosad among others, as the Bengal Painters’ Testimony (B. P. T.). It was done by gleaning blocks of the images from private collections and publishing houses such as Jugantar, Visva-Bharati, Prabasi, and Modern Review. What did this landmark publication seek to achieve? |

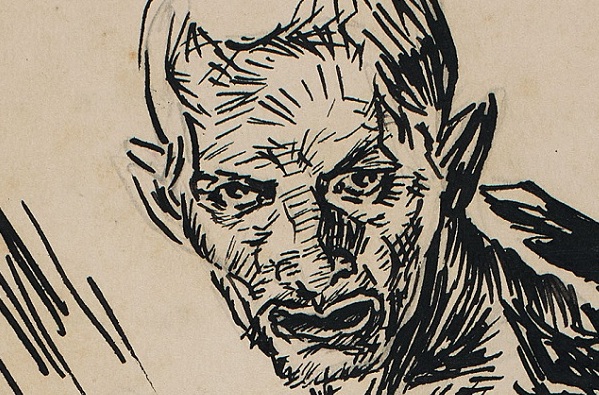

Chittaprosad

Halisahar, Chittagong (detail)

Ink on paper

Collection: DAG

|

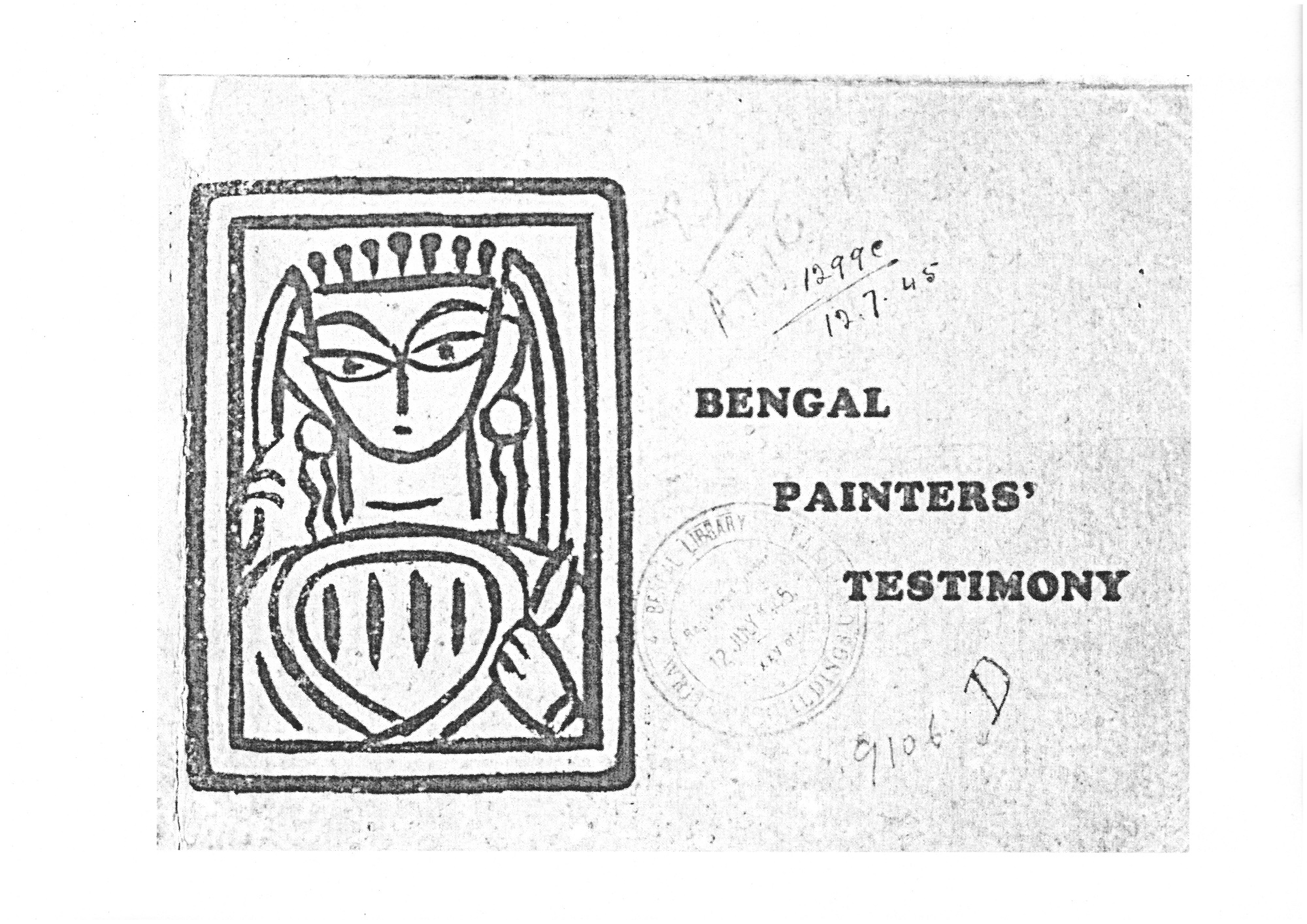

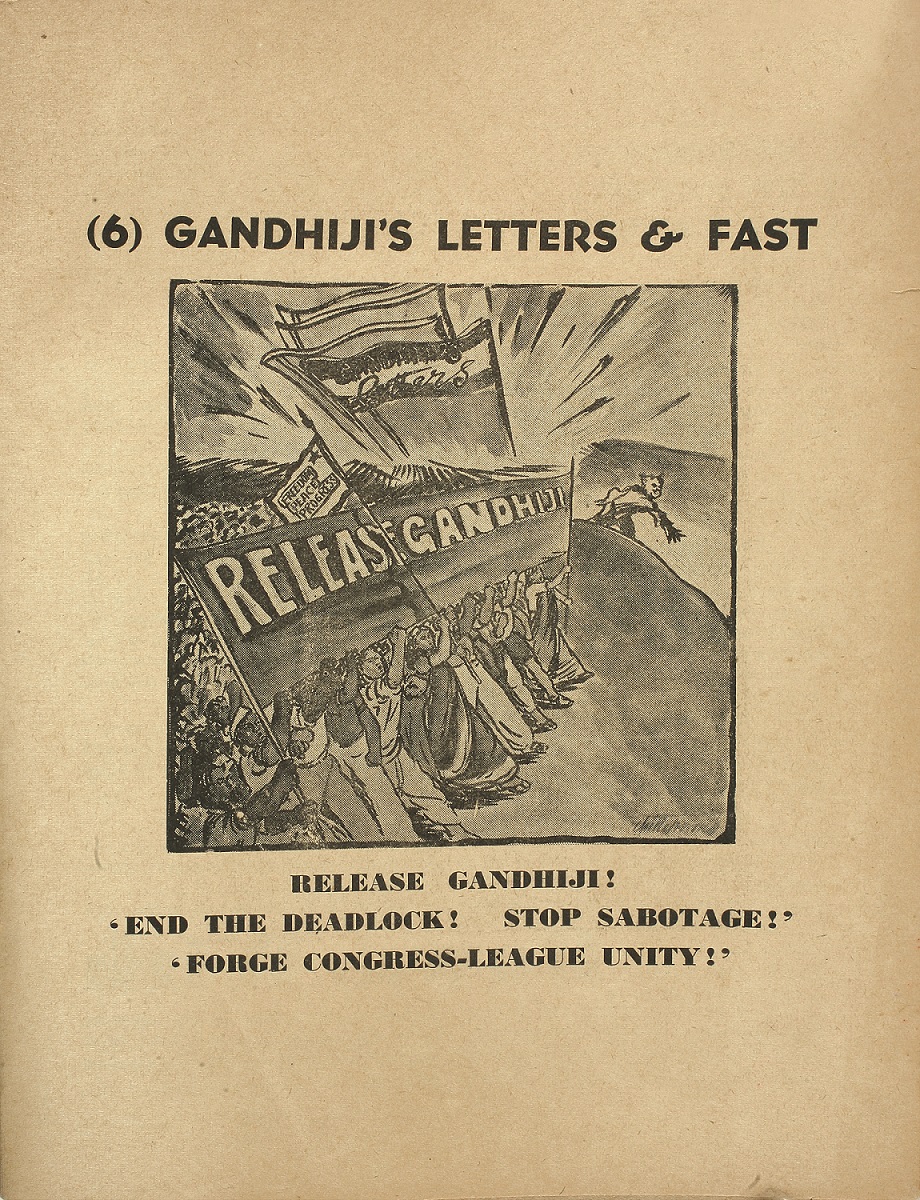

The slim volume had two clear concerns as Sarojini Naidu mentioned in the Foreword— to visibilise the Bengal Famine of 1943 to the rest of India, information regarding which was usually censored in the mainstream press, while the other concern was fundraising for the famine relief fund. The album consists of plates of artworks with their titles and the artist's name, with few other details of the artworks, but represents a moment of resistance by the artists of Bengal who decided to highlight awareness of the famine as part of the larger political struggle for freedom. |

|

|

Bengal Painters' Testimony

Cover page

Image courtesy: National Library, Kolkata

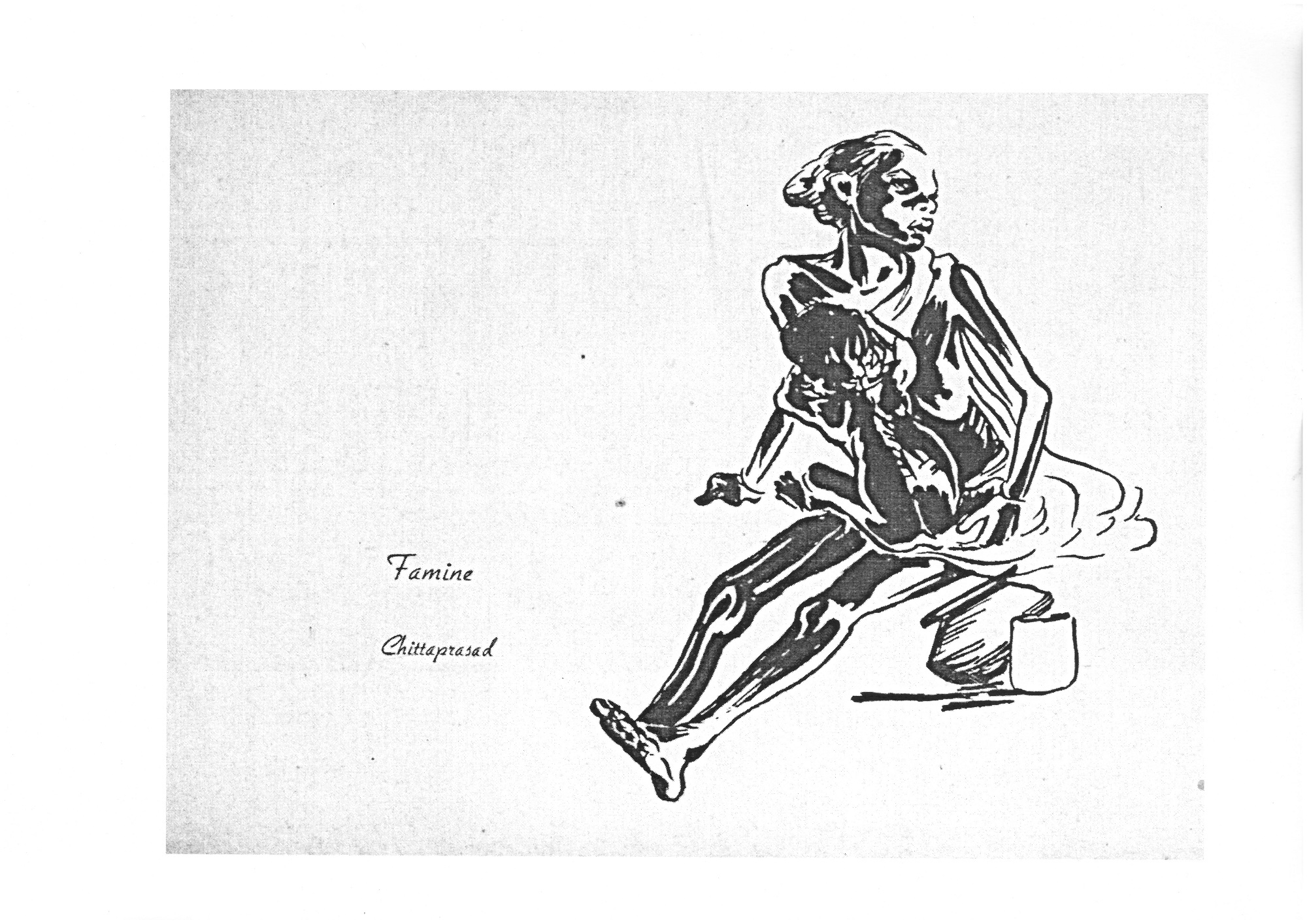

Bengal Painters' Testimony

Famine by Chittaprosad

Image courtesy: National Library, Kolkata

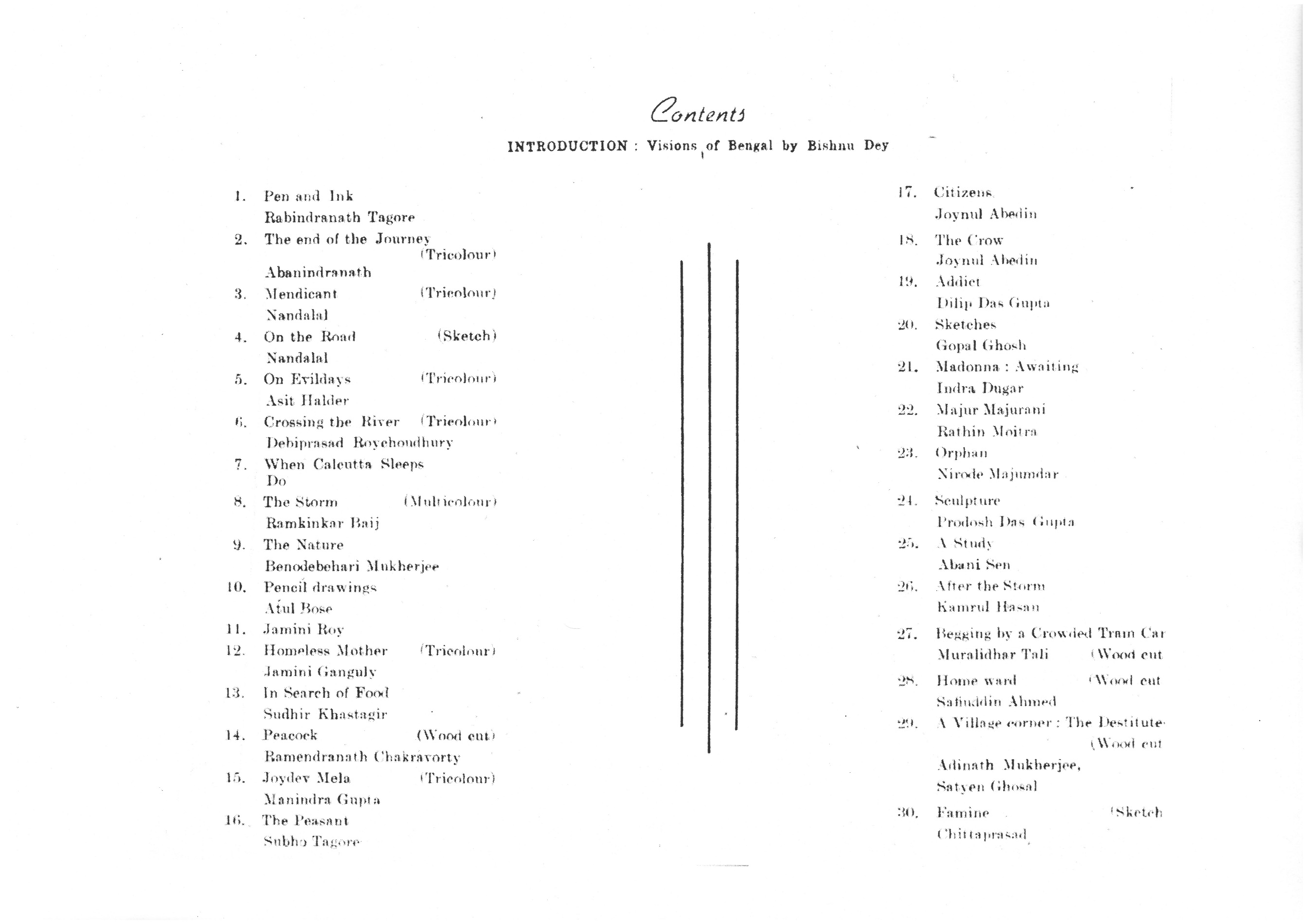

The Bengal Provincial Students’ Federation organised the first exhibition with the artworks responding to the Bengal Famine, followed by the publication of the testimony at the Eighth Annual Conference of the A. I. S. F. in December 1944. The initiative brought forward divergent discourses. The act of making the famine visible was considered a patriotic act in itself and a ‘homage of love and pity to the vast anonymous legion of hunger-stricken and the heroic people of Bengal’ as formulated by Sarojini Naidu in the foreword, although all the artworks that are published there do not necessarily deal with the famine (by representing it, for instance); and a few of them were not even made in the same decade. The testimony presents artworks from artists who were part of the Santiniketan school, Bengal School of Art, and Calcutta Group as well as others like Jamini Roy, Zainul Abedin, Quamrul Hassan, Murlidhar Tali, and Chittaprosad, who were not explicitly part of artists’ collectives. The price of the album was set at rupees five, which was a significant decision taken to make the prints of so many artworks available in one album. |

|

|

Bengal Painters' Testimony

Contents page

Image courtesy: National Library, Kolkata

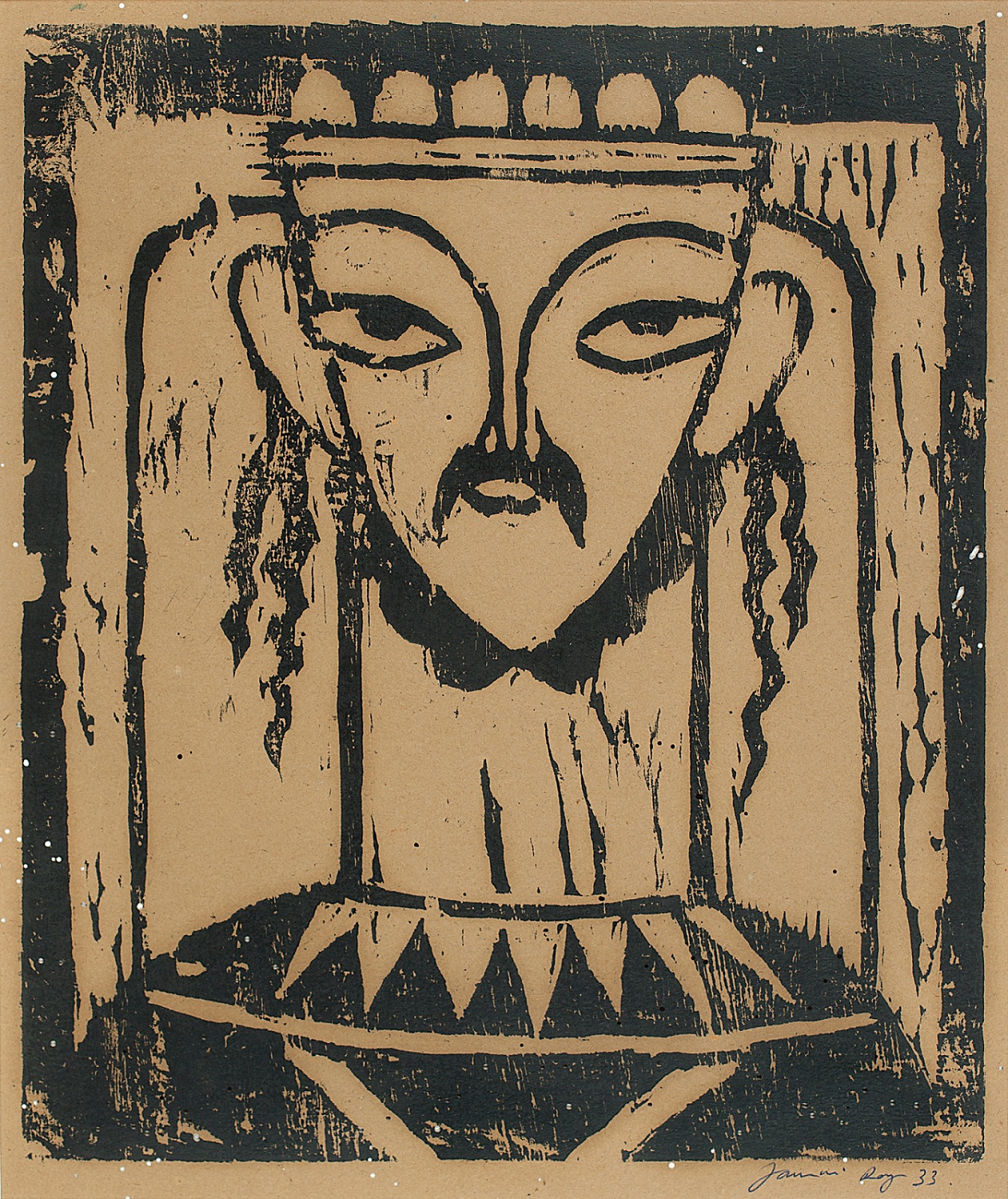

Jamini Roy

Untitled

Woodcut on paper

Collection: DAG

Poet and art critic, Bishnu Dey, in the introductory notes titled, Visions of Bengal, provides a comparative analysis of the existing schools and delineates Jamini Roy as a third pillar, who had been experimenting with the notion of blending ‘folk art’ with the notion of modernity. Alluding to the formation of the Calcutta Group (1943) that strode forward with the ‘progressive’ language in visual art, Dey places Jamini Roy as an epoch-maker for the ‘varied movement in the art world’ of his generation. |

|

|

Bengal Painters' Testimony

Prodosh Dasguupta

Image courtesy: National Library, Kolkata

Bengal Painters' Testimony

Joynul Abedin

Image courtesy: National Library, Kolkata

Prodosh Das Gupta

Genesis II

1982, Bronze, 28.5 x 15.0 x 13.7 in.

Collection: DAG

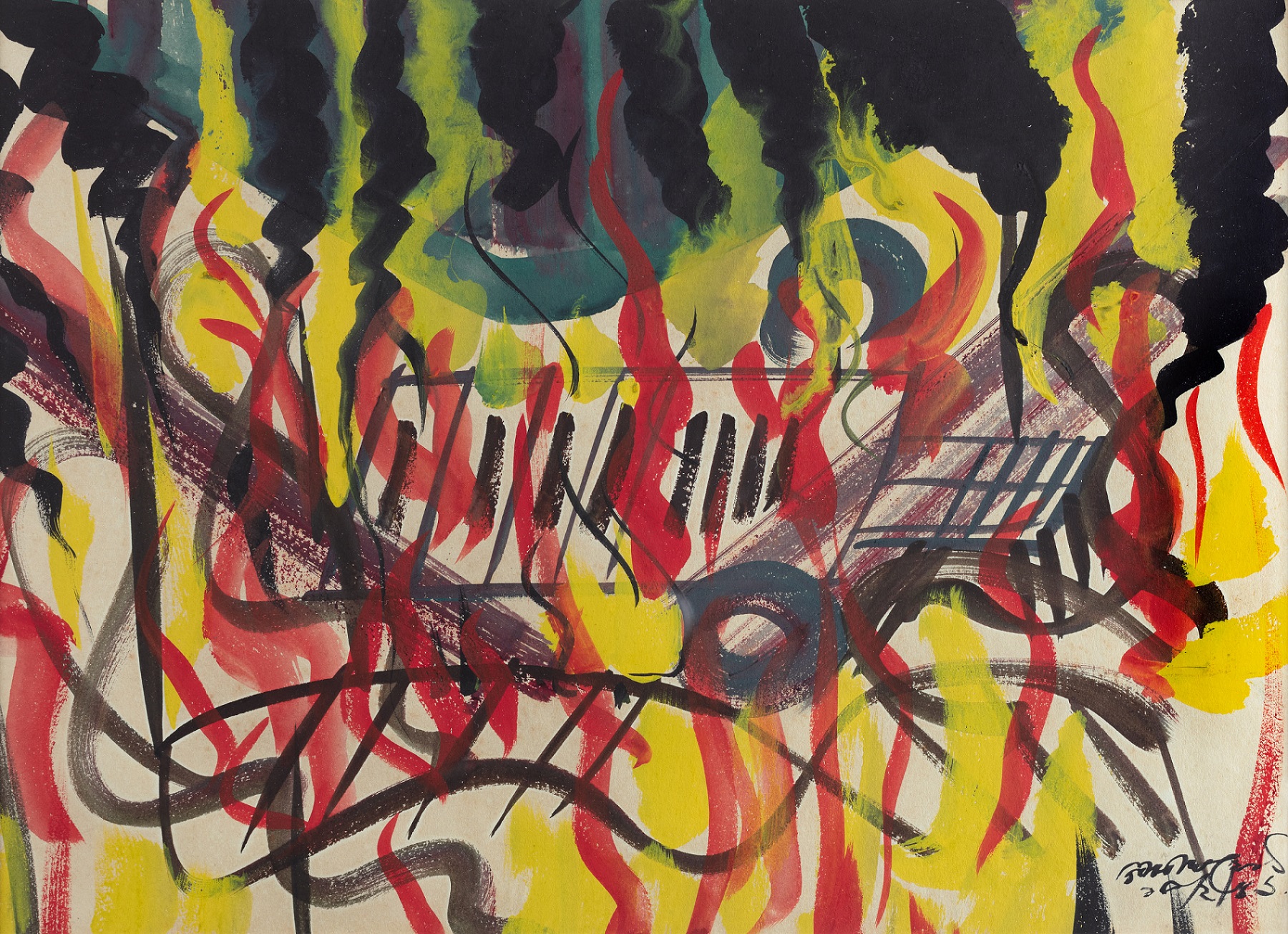

in the first half of the 1940s, early in the careers of most of these artists, a group of practitioners across disciplines had been thinking of coming together to reflect on the series of political and social incidents marking life in India and Bengal—'The years of 1910-43 were among the most eventful in our recent history,' writes sculptor Prodosh Das Gupta. 'This period saw an increasing secularisation in politics and an expansion in the democratic consciousness in our country...with the great impact of the 2nd World War, perceptible social, political, and economic changes made inroads into the lives of the Bengalees.’ ‘Added to that, the horrors of the Bengal famine of 1943 shook the very bases of the old values of humanism...The barbarity and heartlessness all around moved us, the members of the Calcutta Group, deeply. Some of our members were even driven to the periphery of the Marxist philosophy of communism. Sporadic outbursts were evinced in the other creative fields as well. Indian People’s Theatre Association and the Anti Fascist Writers and Artists’ Associations were born about the same time with direct and tacit support of most of the well-known intellectuals; writers, artists, actors, dancers, musicians, and filmmakers. Thus the birth of a second renaissance in Bengal was in the offing, as if automatically under the compelling situation to forge a new cultural revolution.' |

|

|

Gopal Ghose

Untitled

1946, Gouache on paper pasted on mount board, 10.0 x 13.5 in.

Collection: DAG

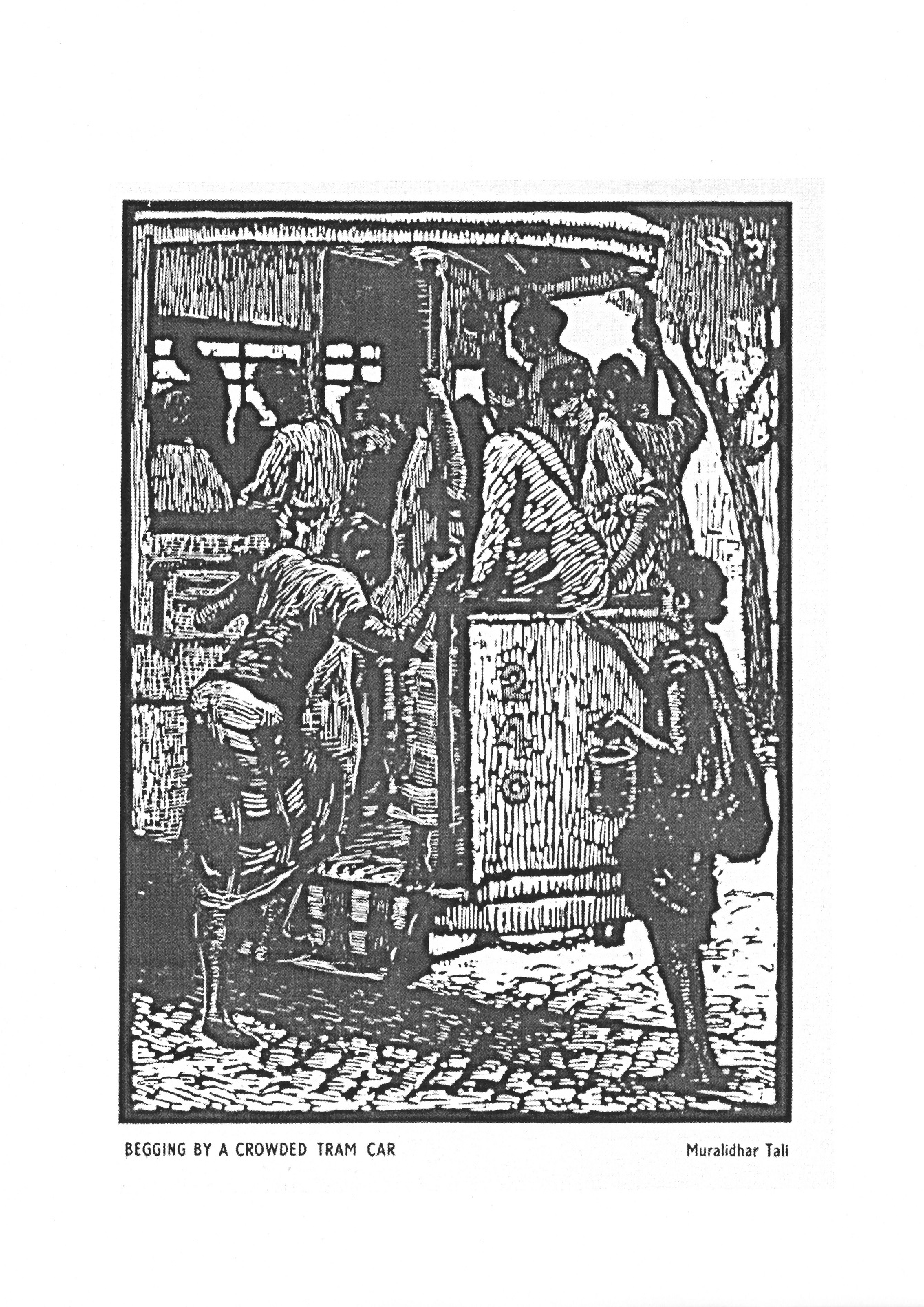

Bengal Painters' Testimony

Muralidhar Tali

Image courtesy: National Library, Kolkata

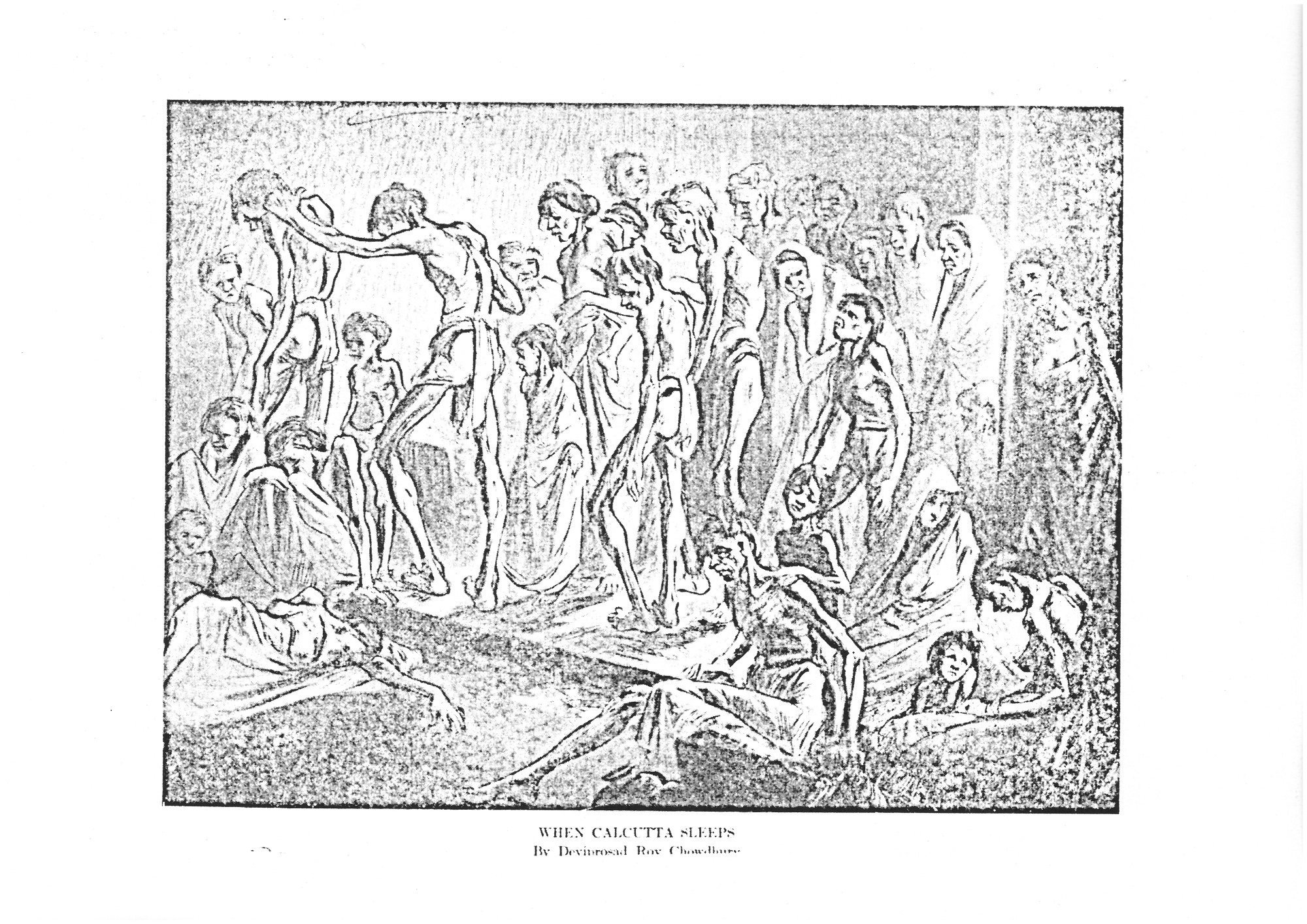

Bengal Painters' Testimony

Deviprasad Roy Chowdhury

Image courtesy: National Library, Kolkata

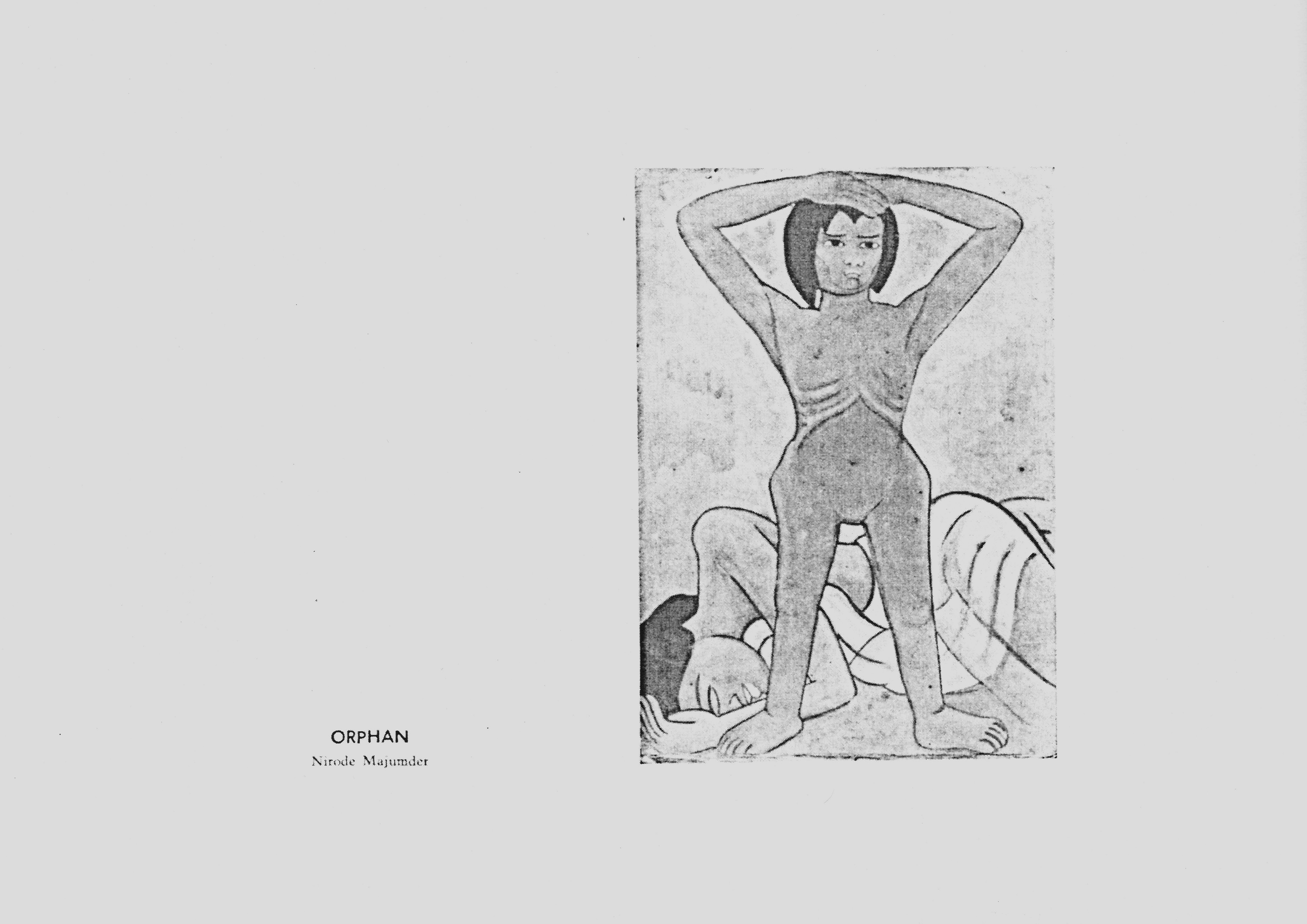

Dey also talked about artists such as Zainul Abedin, Murlidhar Tali, Gopal Ghose, and Surya Roy pointing out their new artistic approach in ‘Visions of Bengal’. A new batch of artists actively sought to document the famine by fostering new methods of sketching in the streets using cheap materials like newsprint paper, brown wrapping paper, cheap ink, charcoal, and graphite. Politically, their stance was not too removed from the members of the Calcutta Group although they did not adhere to the ‘neo-primitive’ language of Jamini Roy. The B. P. T. played a crucial role in circulating (some) graphic representations of the famine alongside other artworks on a national level while artists like Somnath Hore and Chittaprosad, among others, took part in the onsite circulation of the news of famine by postering. In his book Hungry Bengal, Chittaprosad would write about their postering work across Bengal, in the teeth of opposition and censorship. |

|

|

Chittaprosad’s early drawings published in The Student Journal of the All-India Students’ Federation, July 1943

Collection: DAG

Bengal Painters' Testimony

Nirode Majumder

Image courtesy: National Library, Kolkata

Qamrul Hassan

Untitled

Linocut on paper

Collection: DAG

Somnath Hore

Untitled

Etching on handmade paper

Collection: DAG

Writing on the context of the Bengal Famine of 1943, Amartya Sen highlighted an argument on registering suppressed information about this social horror in the public memory through graphic representations of it—'the need to understand the pervasive role of ‘false consciousness’ and of ‘objective illusion’— central to Marxian theory—in explaining social comprehension and the choice of action and non-action remains profoundly important. This applies to other types of social deprivation as well (involving class, gender, race, and nationality), and the contribution made by greater social awareness can be truly profound. A major push in depicting the famine came from The Communist Party of India as a lot of artists, from within the party as well as outside, across disciplines, came to a common ground in the context of the social responsibility of artists. The Communist Party of Chittagong emphasised postering at various marketplaces to visualise the ongoing famine and provided artists with brush and ink. Somnath Hore, another artist-activist who portrayed the famine, recalls, ‘When I came to draw my first poster, I merely enlarged the cartoons of Chittaprosad, and a few others that appeared in the People’s War, the Party’s English weekly. My friend would take them away and put them on the trees in the marketplace or on the walls of the village natmandir’ (a public playhouse). |

|

|

Chittaprosad

Purna Shashi

Ink on paper

Collection: DAG

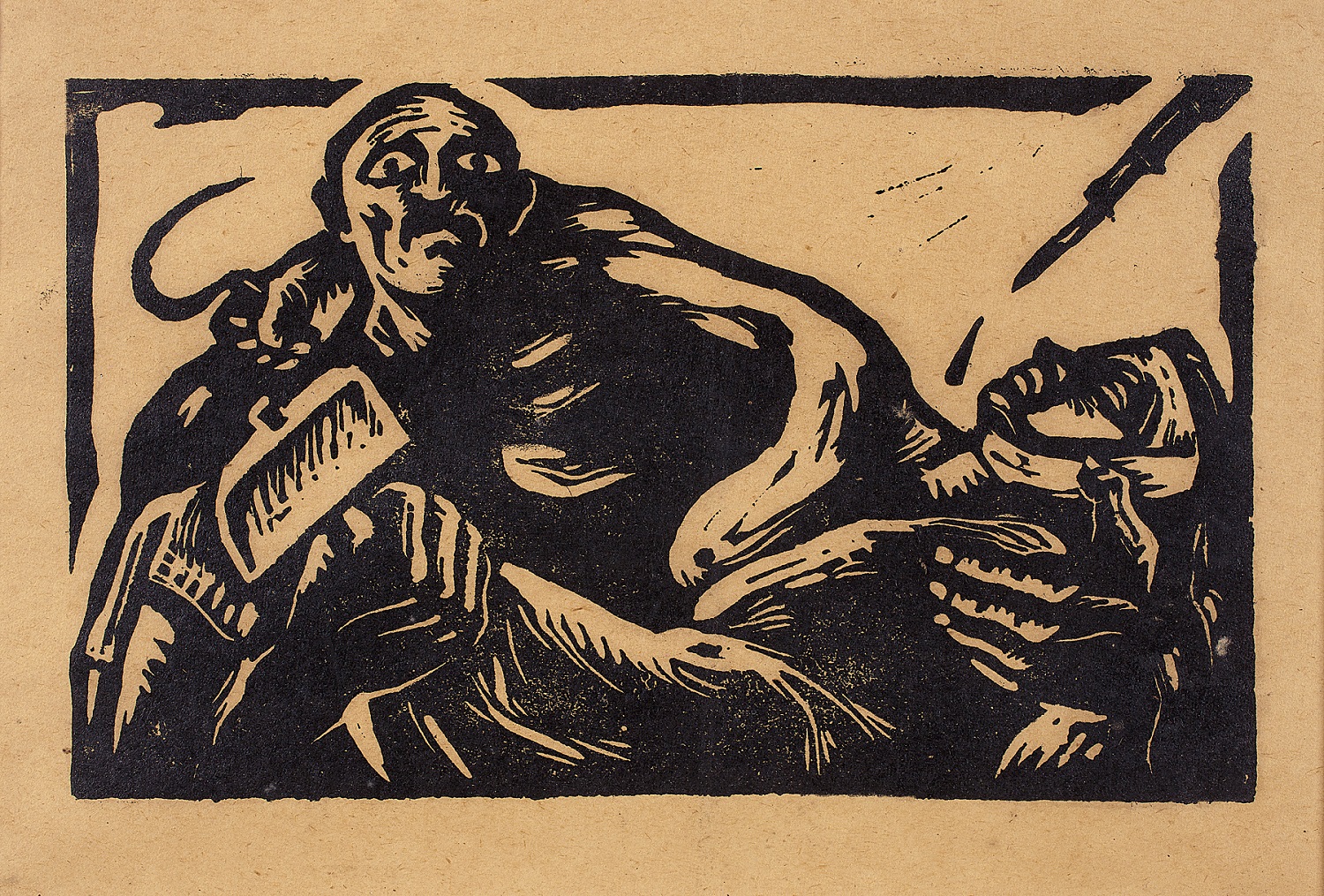

Zainul Abedin

Untitled

Woodcut on newsprint pape

Collection: DAG

A handful of the drawings, at times with short texts added to them, by Zainul Abedin, Chittaprosad, and Somnath Hore, made on the streets of the cities, suburbs, and villages of Bengal, had been published in the C. P. I. organs, in the form of books like Chittaprosad’s Hungry Bengal with drawings and notes representing famine in the district of Midnapur, Ela Sen’s Darkening Days with famine drawings by Zainul Abedin, and the B. P. T. The sharing of these images happened across various layers and public spheres. The sites of famine had not remained fixed physical locations anymore; they had been mobilised. If we consider the artist’s studio as the ‘primary site of meaning’-making for the artist, as Daniel Buren would put it, marking it as a separate site where the artist is involved in a self-affirming discourse, for artists like Somnath Hore, Chittaprosad, and Zainul Abedin, the studio itself became a mobile space, so that image production was based on simultaneous observation and contemplation, and at times, for the posters, the sites of making and/or the sites of engagement were also the sites of sharing. |

|

|

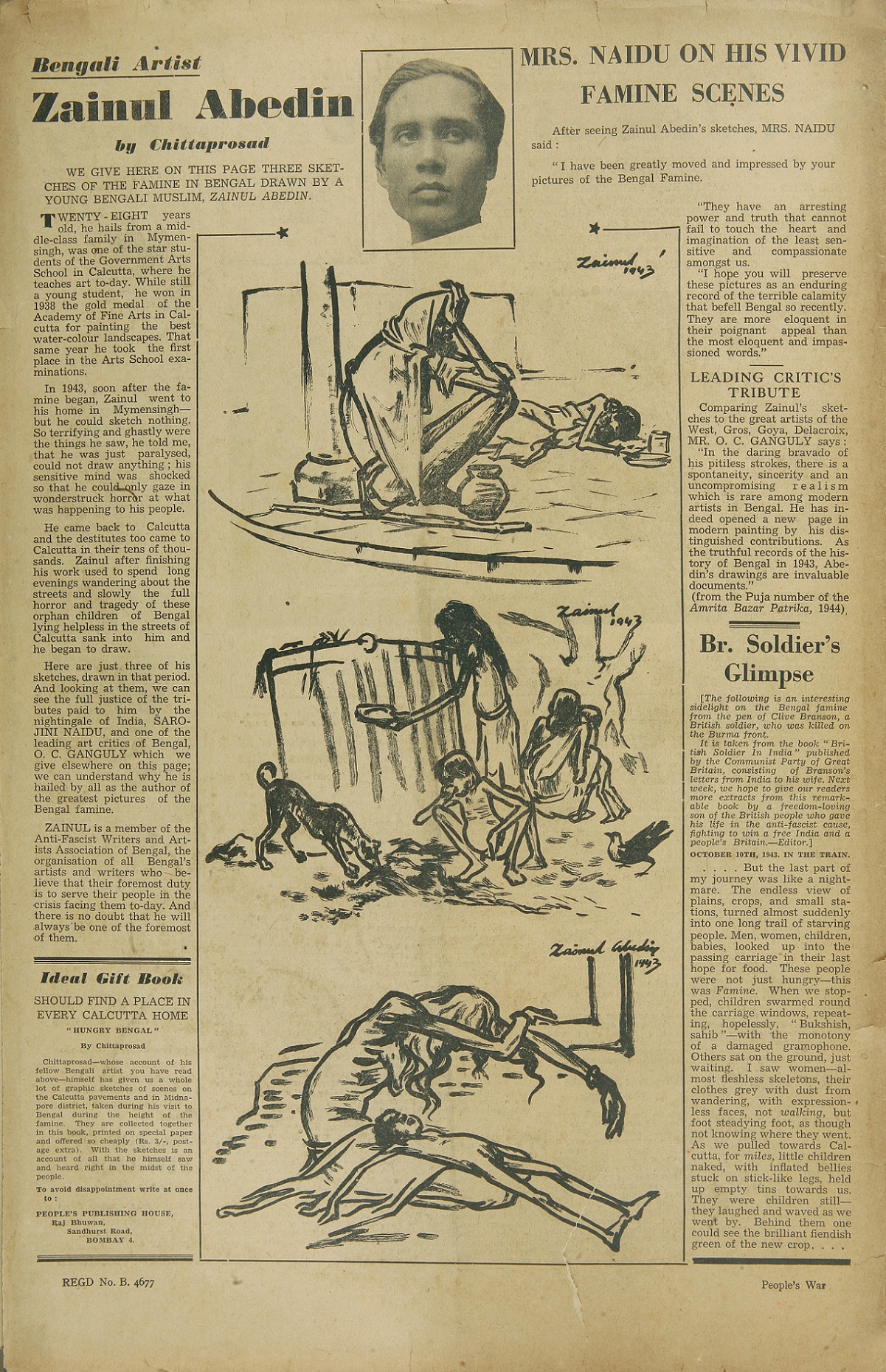

People’s War, Sunday, January 21, 1945, Vol. III No. 30—Chittaprosad on Zainul Abedin

Collection: DAG

Chittaprosad

Halisahar, Chittagong

Ink on paper

Collection: DAG

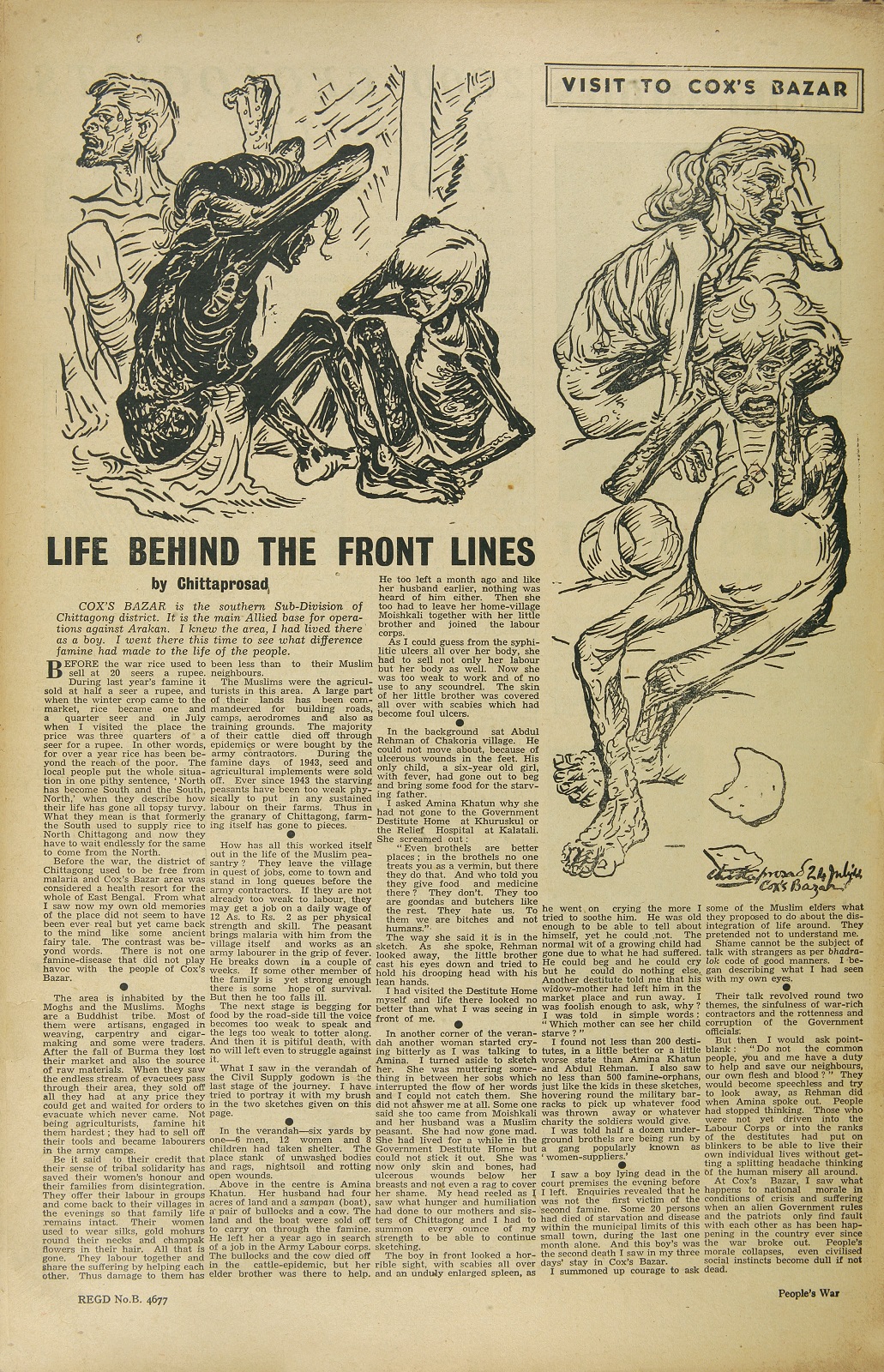

People’s War, Sunday, September 24, 1944, Vol. III No. 13—Chittaprosad’s report on the impact of famine in Cox’s Bazar

Collection: DAG

Chittaprosad's depiction of famine, spanning drawings, posters, short writings, and reportages, resonates profoundly with its audience across various formats he engaged with during wartime. His famine drawings transcend mere representations of collective victimhood; instead, they meticulously portray individuals. Accompanied by brief notes detailing the circumstances, and occasionally names, these artworks encapsulate a nuanced narrative of the human experience amidst the crisis. Apart from the drawings that had been published in the C. P. I.’s organ People’s Age (People’s War after 1945), the journal he maintained during his visit to Contai in Midnapore, was published as Hungry Bengal. In the entire engagement, he had with the city, suburbs, and villages of Bengal during the famine years, his political stance had been translated into that of a humanist observer and listener, so that, simultaneously, the artist-journalist became an ‘activist-agitator’. Thus, even without explicit affiliation with artists’ groups, this moment in time was such that the crisis provoked by the famine allowed a disparate group of artists’ works to be brought together for a common agenda—to end hunger and draw public ire at the spectacular political failure of the colonial and provincial governments of India during the Second World War. |