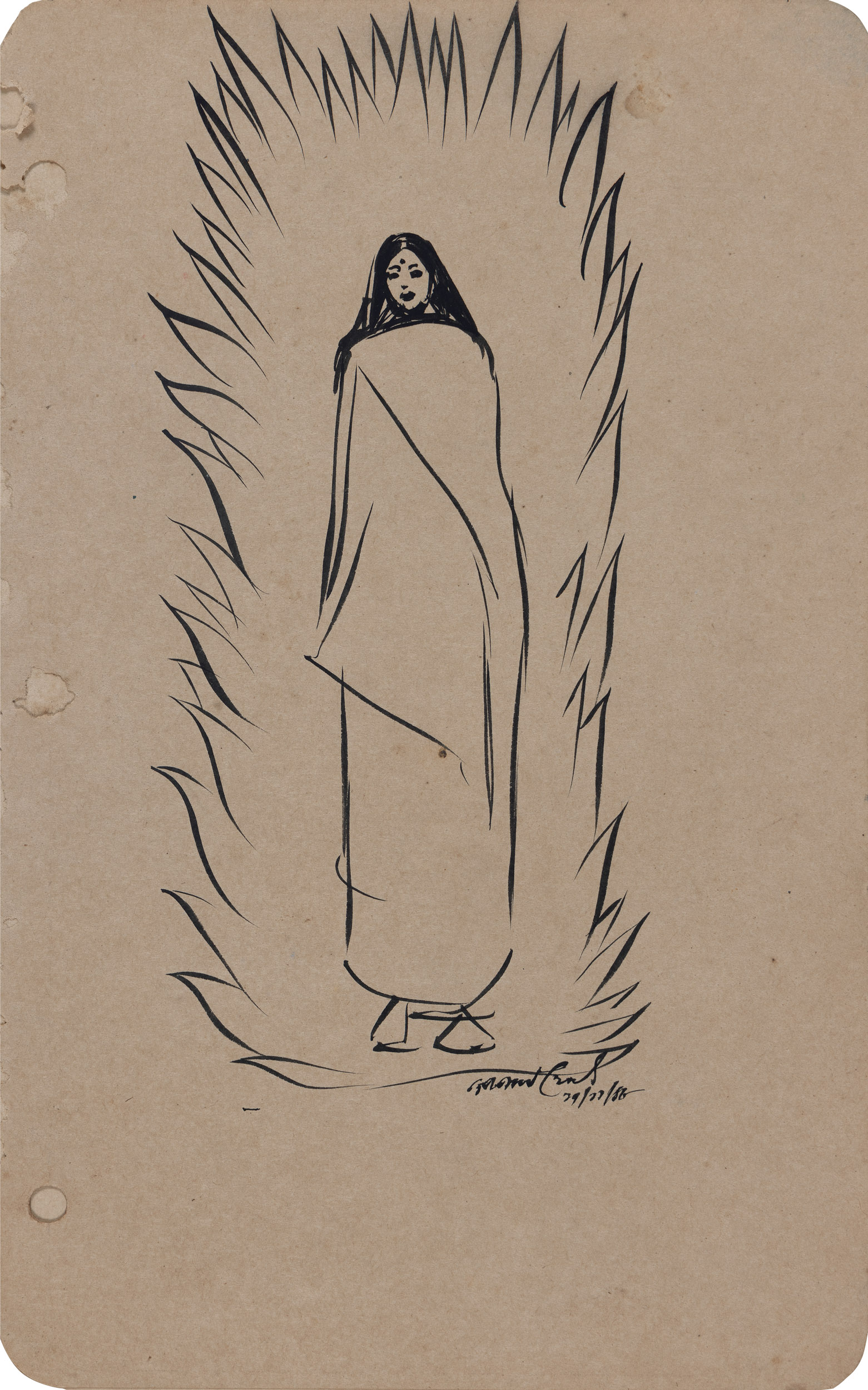

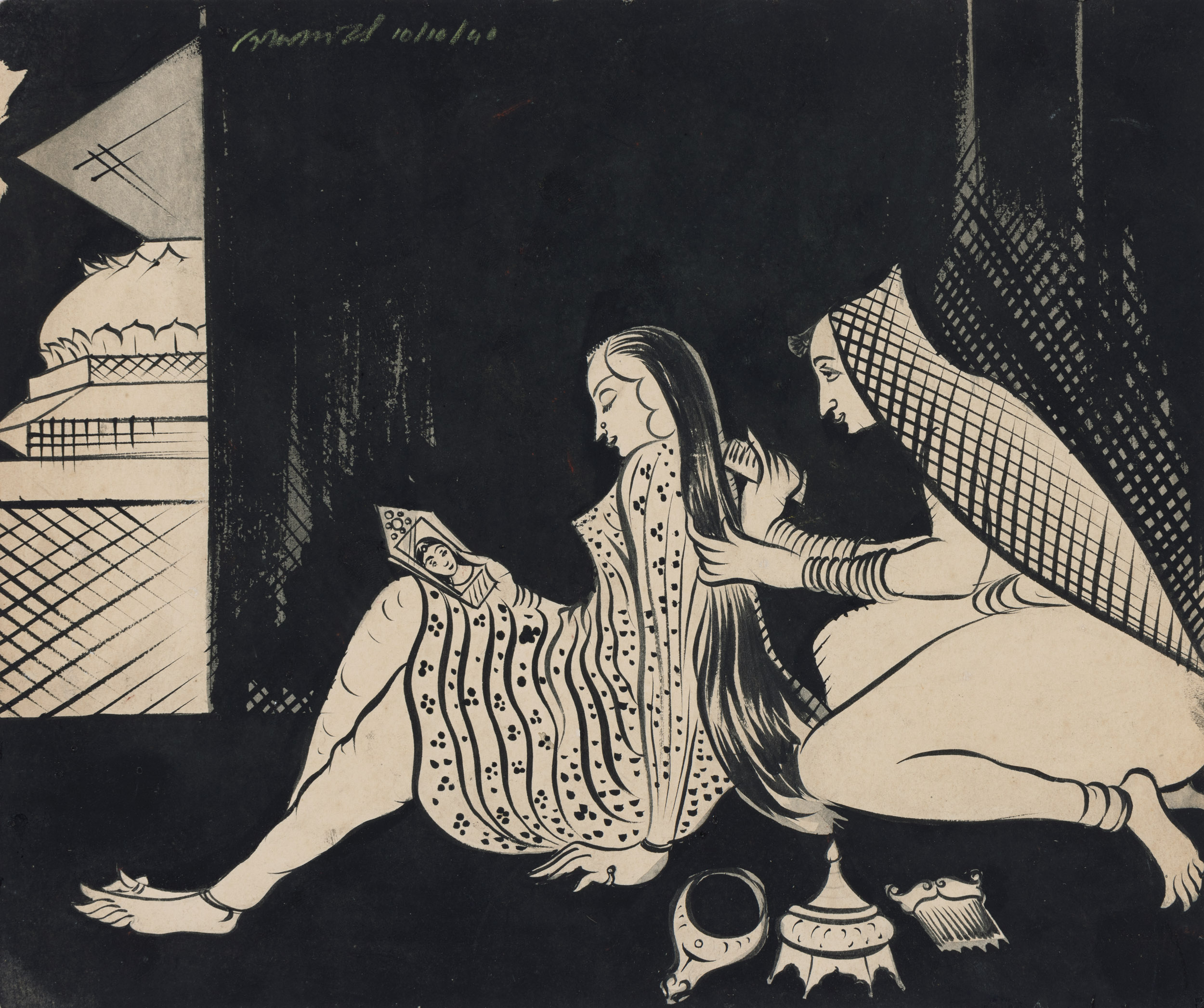

Witnessing Nature: The Art of Gopal GhoseThe Editorial Team January 01, 2024 Gopal Ghose (1913–1980) was a prominent Indian artist known for his significant contributions to the world of modern Indian art. Born in Kolkata, India, in 1913, Ghose grew up in a vibrant cultural environment that played a crucial role in shaping his artistic sensibilities. His artistic journey was characterized by a unique blend of tradition and modernity, reflecting the diverse influences he encountered throughout his life. In this photo essay, we will take a closer look at the dynamics of his friendship with the eminent art critic and collector, W. G. Archer—who set a course for the appreciation of Indian arts across the world; and Ghose’s own words and writings, which form an enigmatic archive of broken utterances, searching for meaning. |

Gopal Ghose

Untitled

Gouache on paper, c. 1950, 17.8 × 28.4 cm.

Collection: DAG

|

Gopal Ghose's programme for rejuvenating modern art was by abandoning a close studio practice for the outdoors. Bearing the trauma of the temporal world, however, where he saw the horrors of communal violence and Partition, he trained an eye on nature that was intimate, sensitive and reflexive of his own inner state, rather than simply imitating a view out there. In 1945 he found an unlikely confidant in W.G. Archer, a British member of the Indian Civil Service known for his engagement with Indian folk art and his advocacy for independence and justice. The encounter unfolded in Calcutta, where Archer spent several days with Ghose, meticulously noting down the artist's musings, aphorisms, and reflections on life, art, and personal experiences. Archer's intention was to write an essay on Ghose, but the project was never completed, leaving behind a rich archive of insights into Ghose's artistic journey. |

|

|

Ghose, at the age of thirty-one, was grappling with the challenges of making a living as an artist. Despite financial struggles, he expressed contentment in discovering his signature style, a visual language that allowed him to express himself authentically. The enigmatic statement, ‘I am the prince of the purple land. I am the iron rod – my sex pleasure is of my paint, not of your family politics,’ reflects Ghose's commitment to his artistic pursuit, detached from societal norms and political entanglements. Archer, far from the stereotypical colonial bureaucrat, engaged deeply with Indian culture, folk art, and tribal poetry. His socialist beliefs aligned with the cause of Indian independence and justice for tribal communities. The friendship between Archer and Ghose was facilitated by their mutual acquaintance, poet Bishnu Dey. Archer's notes, preserved in the British Library, reveal a series of conversations where Ghose shared aphorisms, poetic self-revelations, childhood memories, and reflections on his artistic journey. |

|

|

In these intimate sessions, Ghose unveiled his vulnerabilities, oscillating between personal and professional insecurities and unwavering confidence in achieving his artistic goals. Archer's meticulous recording captured Ghose's thoughts on art, life, and the transformative moment he referred to as his 'crisis' or breakthrough in early 1945. The artist's path to maturity unfolded as he navigated challenges and embraced his unique visual idiom. The archive includes drafts, repetitions, and revisions of Archer's essay on Ghose, as well as a questionnaire sent by Archer and Ghose's detailed responses. The budding art historian recognized the gem he had discovered but struggled with how to present it to a sceptical world. The narrative that emerges from the archive paints a portrait of an artist finding his voice amid personal and professional turmoil, and an art historian grappling with the responsibility of unveiling a talent to an unready audience. |

|

Ghose's anguished and poetic declaration, ‘For paint’s sake, seek no more of my within’s wounded womb. I am here healthy with the rays of colour. That is the countable coin of my coiled skull,’ encapsulates his commitment to the purity of artistic expression, devoid of external influences. The juxtaposition of Ghose's internal struggles and external recognition through Archer's notes creates a layered narrative, highlighting the complexities of artistic self-discovery and the challenges of conveying such revelations to a wider audience. |

|

|

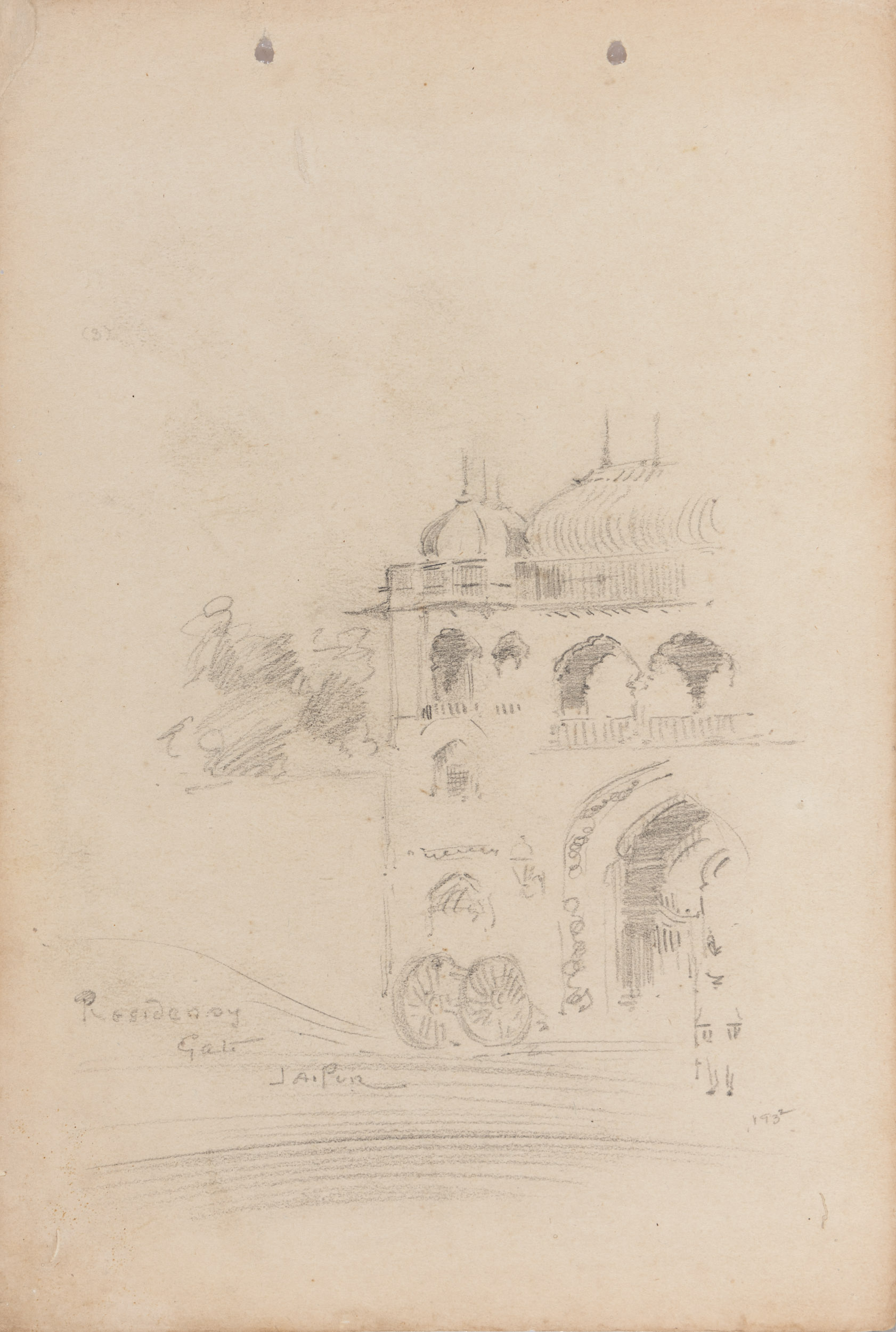

Gopal Ghose began his formal artistic training at the Maharaja School of Arts, Jaipur, followed by the Government College of Art and Craft in Chennai, where he studied under eminent artists like Devi Prasad Roy Chowdhury. Some of his early sketches from the 1930s depict views of Rajasthan where the artist highlighted the land’s mythic significance in the context of Bengal art as well. During the 1940s, Ghose was associated with the influential art collective known as the Calcutta Group, which played a pivotal role in shaping the trajectory of modern art in India. The group, comprising artists like Pradosh Dasgupta, Rathin Maitra, Nirode Mazumdar, Paritosh Sen and others, aimed to break away from the academic traditions and explore new avenues of expression. This association exposed Ghose to diverse artistic styles and perspectives, influencing his own artistic evolution. |

|

Reminiscing about his time in Rajasthan, Ghose told Archer, ‘When darkness came early I woke up and moved by the bank of riverside and tearful lake yard. The Pichola lake of Udaipur used me most. I watched early to sunset, waited for hours together, watched everything, watched earthen pot carrier coloured ladies who moved in a most marvellous way and movement that too nursed me utmost. Several types of ages and forms with absolute gesture poises all along, all through the moment, O how sensations were really to a boy of 18 who looked and enjoyed the crankiness of living and lovely nature. This untutored uneducated unaided, waited not only to mark the mystery of the nature but sketched a lot. Oh but, still a lot unsketched left, so vast and endless Nature.’ |

|

|

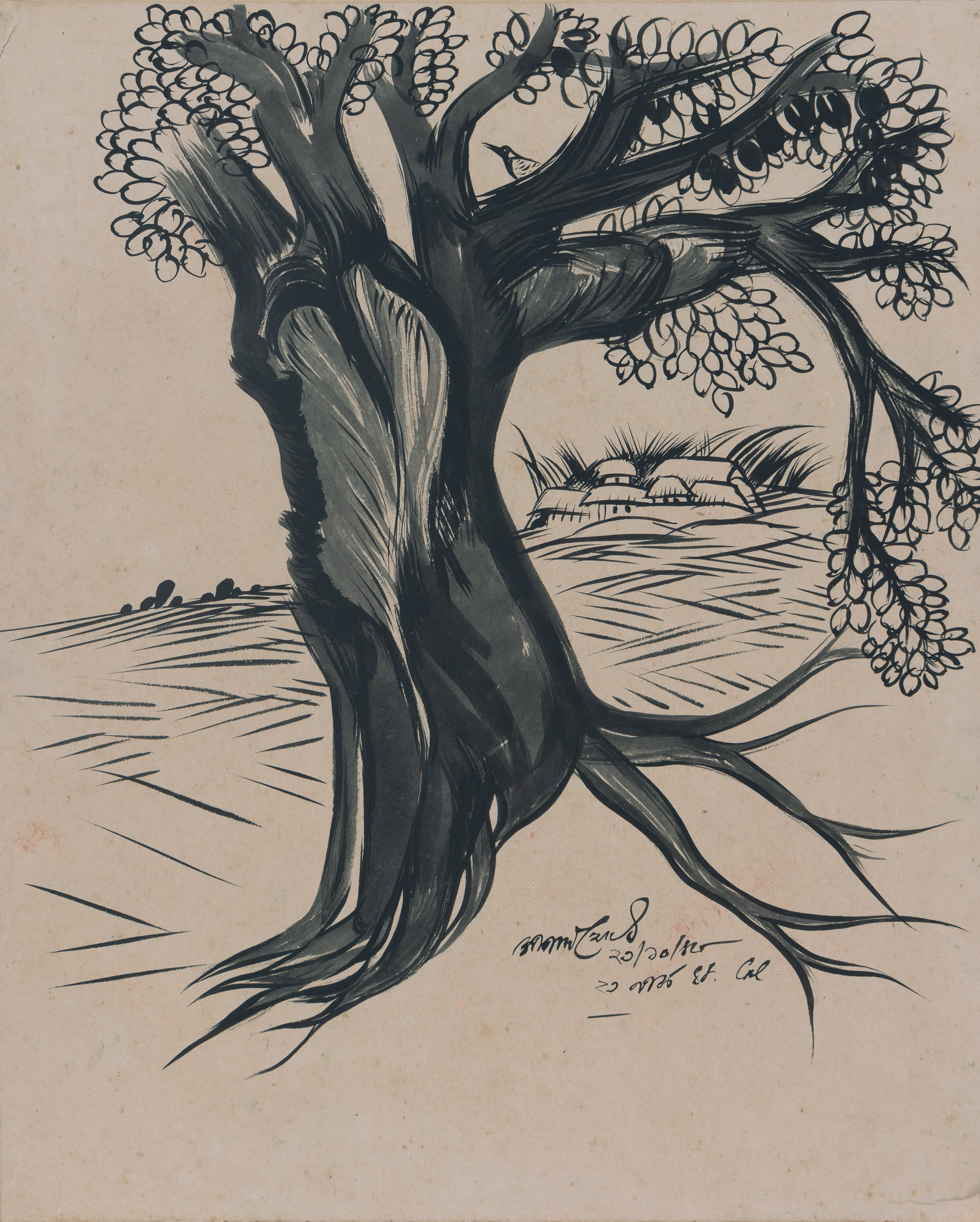

In an unfinished note, Archer would write about Ghose’s sensibility: ‘Among contemporary Indian artists Gopal Ghose is that rare phenomenon, a painter with a poet’s sensibility, a poet whose medium is paint. Paintings spring from his brush in the mad rush of a poet’s frenzy. His mind is a reservoir of images – a tree caught in a darkening storm, a sun descending on a scarlet evening, a field shrieking with yellow mustard. He does not imitate nature, he allows an impression to ferment, to accumulate a charge of feeling, and it is only when the charge is ready that …’ |

|

|

The joy of artIn his autobiographical narrative, Atmakatha (My Story), Ghose writes about his feeling for the natural world: 'The brush embraced me at an early age. I used it to draw my first flower petals. Behind this education lay my father’s encouraging words. He noticed my inclinations toward drawing at an early age and pushed me towards developing it as the highest ideal. Of course, if this ideal has any rewards, or what those rewards are—these are questions that still elude me today. I continue to work, I’m attached to the world of art—these are my rewards. I have given them a simple name—‘joy’. Art means joy or, joy means art. However, in this strange country where our society seems to stand still art has also withered away. There is little love for art, nor is there any urge to embrace it. We can only see pompous statements being made, a lot of running helter-skelter, shouting, but not the habit to sit on a charpoy and do some work.' |

'Here, a big question arises—even as one tumbles about and the noise of shouting threatens to consume the world. Someone will ask, oh wise one—I see you making art, and deriving joy from it, but the question still remains: how do you earn any money? Money, after all, is the god who has survived primordial times down to our modern one. How does one get to see this god? I did not want to see this god, I went out to see the cedar tree instead. My mouth closes in on itself, no answer springs forth. Because art’s worth—what in the markets is termed ‘value’—is not something I considered before starting out on this journey. I started my life with art and will finish with it too, this is a vow I made to myself. This has been enough for the preserver to keep me so far—and has prevented me from becoming a rascal. I like the sun, I feel comfortable when the sun rises—I see a message written in this sunlight—and if this message is pierces my chest, its life will become worthy. That is why when I see the colour of the ripened crop of rice it makes me go crazy.' |

|

A lifelong student of sunlight and the charms of the natural world, Gopal Ghose's legacy endures through his extensive body of work and the influence he had on subsequent generations of artists. Critics of his time, besides Archer, often remarked that Ghose's art was influenced by his preference for the art of the past, rather than what goes by the name of modern art. But isn’t modernism recognised for the special relationship it forges between a modern sensibility and its apprehension of classical forms? Negotiating the two, instinctively and emotionally, has become a standard demand in our increasingly mechanised world of image-production. With Ghose’s works, we see the human hand that makes nature the supreme subject of our consciousness, instead of an object of conquest that lies out there. |

|

|