Winds of Change: Inventing Modern Art in Bombay

Winds of Change: Inventing Modern Art in Bombay

Winds of Change: Inventing Modern Art in Bombay

Charles Gerrard, Female Nude (detail), Oil on canvas, 35.5 X 30.5 in. (90.2 X 77.5 cm.) Collection: DAG

The city of Bombay (now Mumbai) in the 1930s was a place of exciting and pathbreaking artistic experimentations, with a thriving community of artists, connoisseurs, art critics and a public devoted to appreciating art.

The city was home to an art school that, until then, had rarely challenged traditional teaching methods from Western academies of art such as the South Kensington School, but since the late-1910s started striving to modernise and contextualise art to reflect contemporary realities. Additionally, institutions like the Bombay Art Society played a crucial role in nurturing young talent by hosting significant exhibitions and offering artists a strong platform to showcase their creative work. In DAG’s ongoing exhibition, Shifting Visions: Teaching Modern Art at the Bombay School, in collaboration with Sir J. J. School of Art in Mumbai, we tried to trace this moment in the history of modern Indian art through a carefully curated section called ‘Experiments in Modernism’.

Charles Gerrard, The Garden of the Director's Residence, the Sir J.J. School of Art, Bombay, Oil on Masonite board, 20.0 X 24.0 in. Collection: DAG

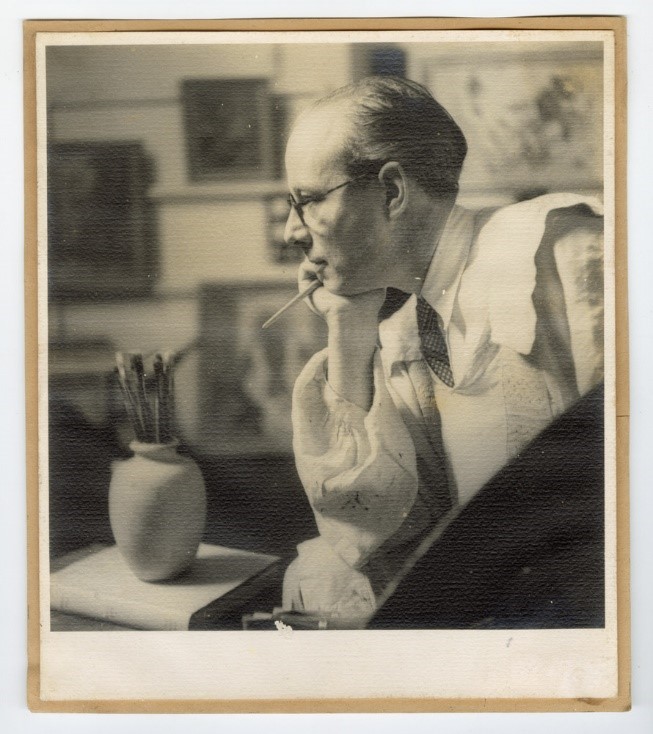

One of the instrumental figures who consciously tried to change the landscape of visual art pedagogy in colonial Bombay was Charles Gerrard. Since its inception, the teaching of art at Bombay school focused on ‘naturalism’; blending the rigorous ‘training of the eye’ that is provided by European academicism with a carefully studied appreciation of the cave paintings of ancient India. This movement began with the Ajanta projects led by the former teacher of Decorative painting and Principal of the Sir J. J. School of Art, John Griffiths, and his students throughout the 1870s, and gained momentum, reaching its peak in the 1920s through the then Principal Gladstone Solomon’s efforts towards the ‘Bombay Revival of Indian Art.’ When Gerrard was appointed Principal in 1936, he introduced students to the major art movements shaping the West and encouraged them to embrace individuality and creative freedom in their work. In essence, he infused new energy into a school preoccupied with reviving the past, breaking the stagnation with a fresh wave of artistic expression.

|

Unidentified Photographer, Portrait of Charles Gerrard, Silver gelatin print on paper, c. 1930. 11.3 x 9.6 in. Collection: DAG |

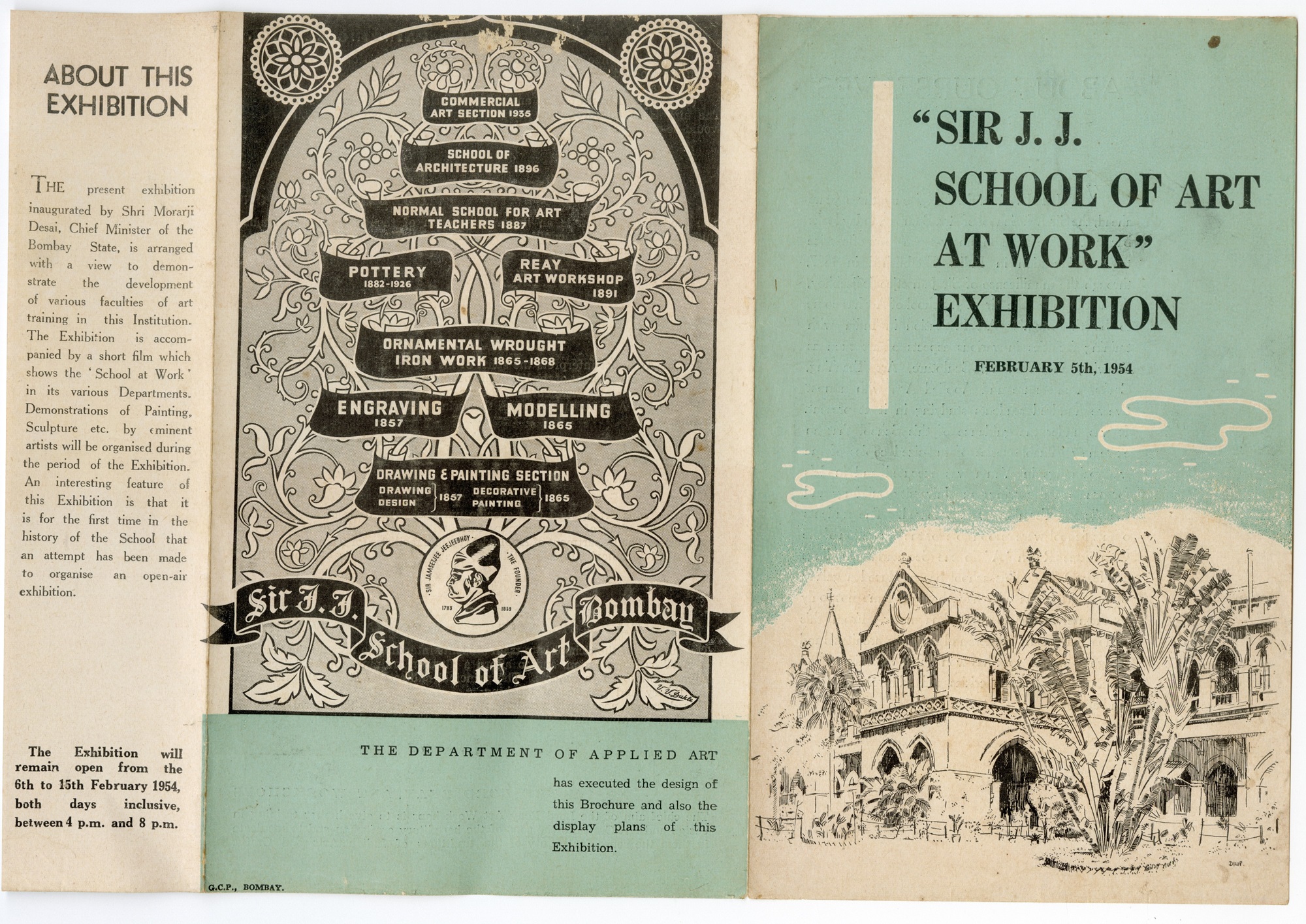

Charles Gerrard also played a vital role in founding the ‘Commercial Art Department’ in 1936 in the School, which later paved the way for the opening of an applied art section. This initiative was enthusiastically embraced by young artists, as it enabled them to refine their skills and secure jobs in the rapidly expanding advertising industry as illustrators and designers. It also brought significant changes to the syllabus and curriculum, broadening the focus beyond traditional fine arts to incorporate emerging design vocabularies.

(Left) Illustrated J. J. school timeline designed by the students of the Department of Applied Art. (Right) The Sir J. J. School at Work' Exhibition Brochure. Print on paper, 1957, 10.0 x 12.0 in. Collection: DAG

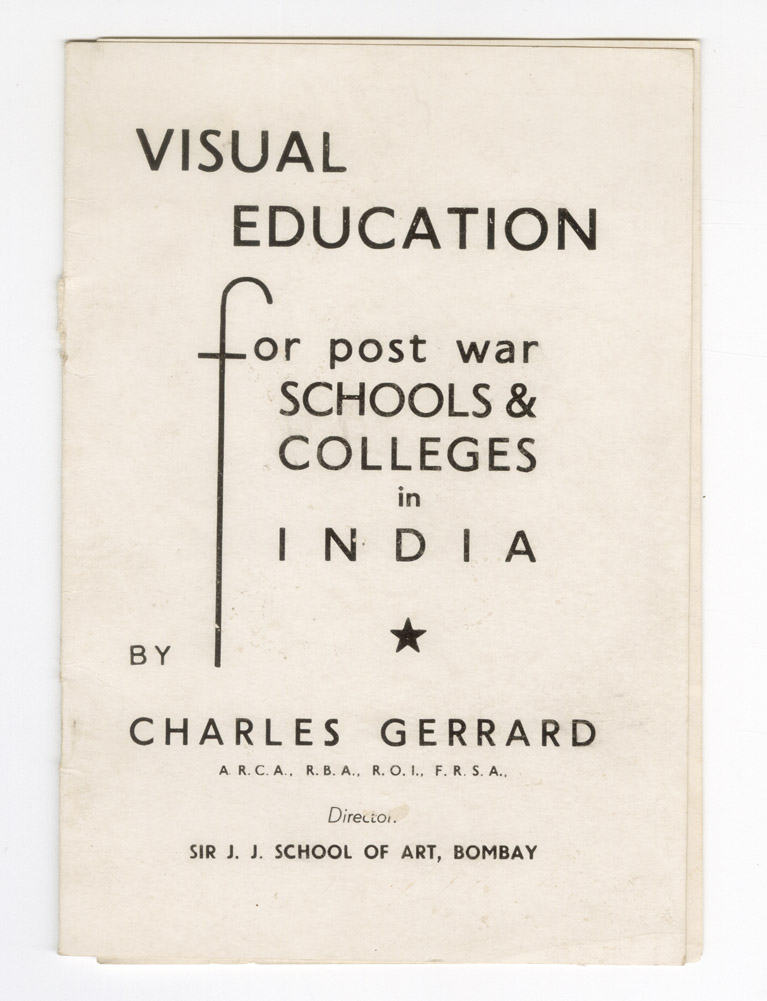

While familiarising students with contemporary artistic approaches and keeping them in tune with global trends—often with disruptive results—he remained deeply aware of the realities of art education in India. His booklet, Post-War Art Schools in India, exemplifies his commitment to understanding, interpreting, and transforming the country’s post-war art education infrastructure. He approached this task by first acknowledging and celebrating India’s rich traditions of painting and sculpture, which often led to his own stylistic departures from Western modernist idioms and into the realms of Indian miniature painting, as was evident in a School exhibition from 1942. This balance of innovation and respect for heritage, which also challenges popular claims about Gerrard’s singular devotion to Western modernism, made him one of the most remarkable art administrators of his time.

|

Charles Gerrard (author), Thacker & Co., Ltd., Bombay (publisher), Visual Education for Post War Schools & Colleges in India, Print on paper, c. 1940, 7.0 x 9.6 x 0.1 in. Collection: DAG |

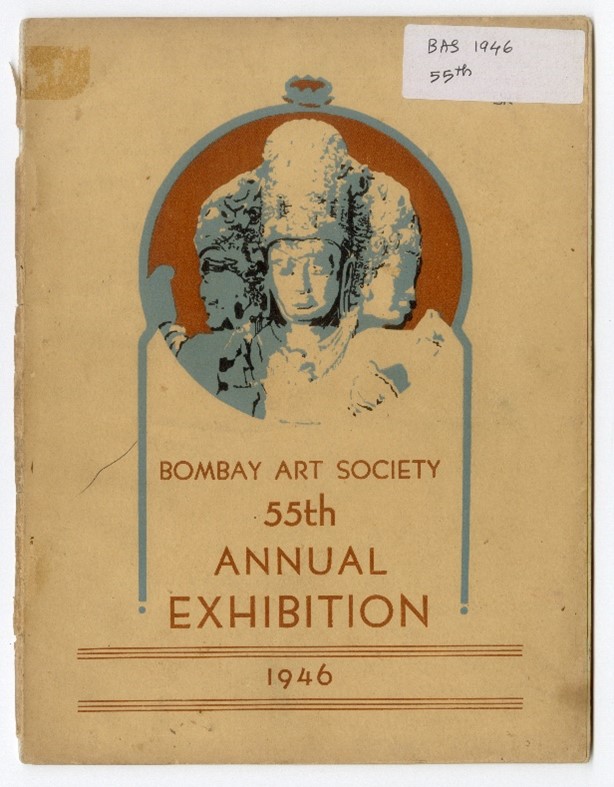

During this period, the Bombay Art Society (B. A. S.) played a crucial role in cultivating public appreciation for the arts while fostering a community of critics, connoisseurs, and collectors. This created a meaningful engagement between artists and a wider audience. Founded in 1888, the Society aimed to ‘encourage art, especially among amateurs, and educate Indians on its true appreciation.’ It also provided a vital platform for young artists to showcase their work. From its inception, the Society’s awards recognised emerging talent, helping the nation identify artistic brilliance. Notably, Gerrard served as a jury member for its annual awards in 1937–38, the year Amrita Sher-Gil received the prestigious gold medal. In 1935, after a long hiatus, the Society revived its annual art journal, featuring black-and-white reproductions of significant artworks and articles addressing contemporary issues in the Indian art scene.

|

Bombay Art Society (publisher), Catalogue of the 55th Annual Exhibition, Print on paper, 1946, Closed size: 9.6 x 7.3 x 0.1 in. Open size: 9.6 x 14.6x 0.1 in. Collection: DAG |

In 1939, Walter Langhammer received the gold medal of the B. A. S. A young diplomat-journalist, Langhammer emigrated from Austria to Bombay in 1938, and joined as the Art Director of the Times of India. He continued painting with rejuvenated inspiration from Indian society, albeit executed in his markedly Expressionistic style. Langhammer, together with Rudolf von Leyden and Schlesinger (both of whom served as jury members to the B. A. S.), changed the landscape of art criticism and appreciation in the city. Young artists found mentors in these figures, who constantly nurtured their curiosity, encouraging fresh art school graduates to explore contemporary artistic trends worldwide. Langhammer was particularly captivated by the country’s vibrant colours, dynamic political movements, and the active participation of ordinary people. In his painting of a woman with a spinning wheel (charkha), both the use of color and the expressive style reflect his deep connection to grassroots politics and the lives of common people.

|

Walter Langhammer, Untitled (Portrait of a Woman at a Spinning Wheel), Oil on canvas. Collection: DAG |

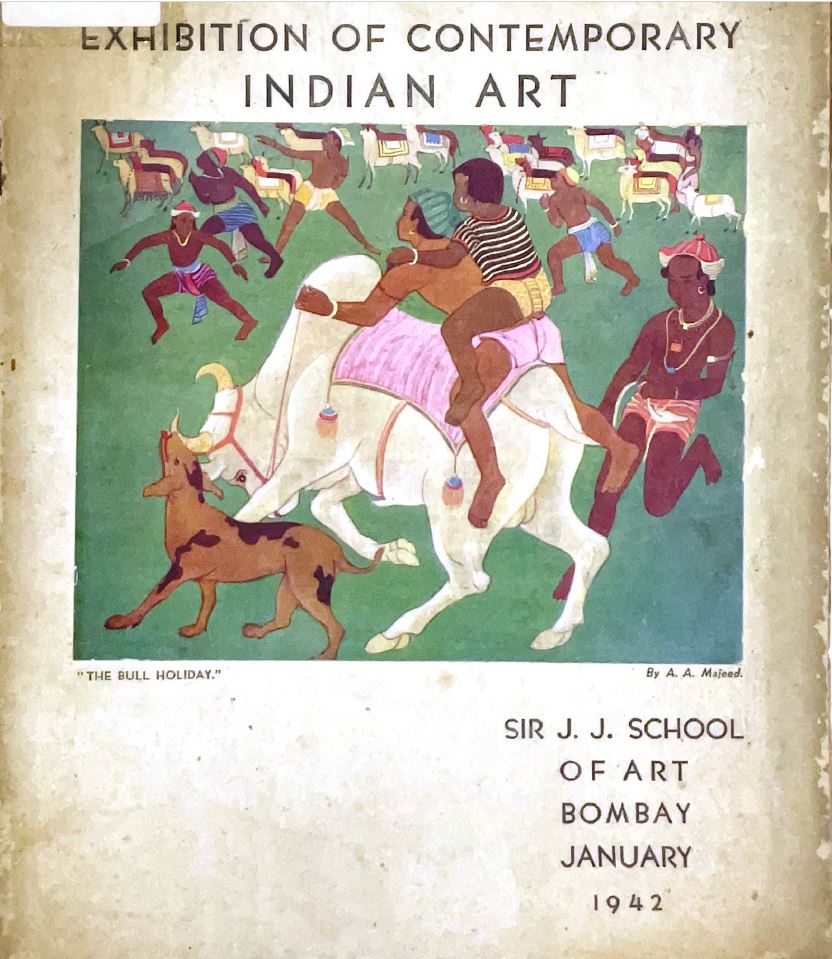

In 1937, four graduates from the J. J. School of Art—P. T. Reddy, Clement Baptista, A. A. Majeed, and M. T. Bhopale—boldly experimented with painting, breaking away from the academic and muralist traditions instilled by the school. Seeking to establish a distinct identity for their innovative work, they formed the group ‘Young Turks’. Their mentor, Charles Gerrard, who had guided them since their student days, later curated their works alongside those of other young artists in the 1942 Exhibition of Contemporary Indian Art at Sir J. J. School of Art, Bombay. This exhibition, titled ‘Exhibition of Contemporary Indian Art’, held in Sir J. J. School of Art, Bombay, marked a phase of transition to progressivism in the history of Indian contemporary painting because of the variety and vibrancy of the voices that resulted from the inclusion of new approaches to teaching and thinking about art, even as the show featured works done in ‘traditional’ or, miniaturist style, all of which constituted the substance of Indian ‘contemporary’ art, produced as ‘a result of much experiment’, as Gerrard sought to define it.

|

Exhibition Catalogue of Contemporary Indian Art curated by Charles Gerrard featuring leading contemporary young artists from Bombay (1942). Collection: DAG |

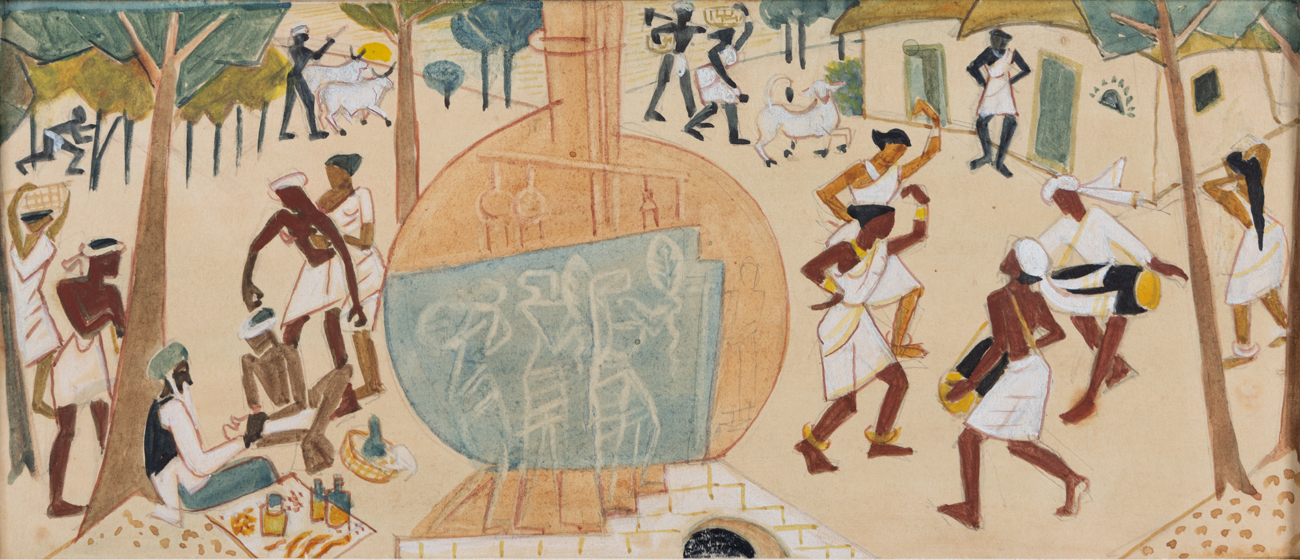

Owing to the ‘nationalist’ politics of the period, artistic production at the J. J. School of Art bore many signs of the time and its people. Many paintings from this period reflected a strong sense of the emergent ‘collective spirit’. K. K. Hebbar’s work, for instance, embodies the Gandhian ideal of returning to the village, yet it is infused with an abstraction reminiscent of Indian folk art, which was also experiencing a revival at the time, and would remain an important source of Indian modernism in its postcolonial years as well. These young and daring artists were unafraid to experiment with mediums and techniques, nor did they hesitate to incorporate symbols that directly reflected the cultural politics of their era, seamlessly weaving political narratives into their art. In the work of artists like Lalita Joshi, for instance, one also saw intriguing syntheses of revived styles and contemporary politics, both communicating their specific charges in unique ways.

|

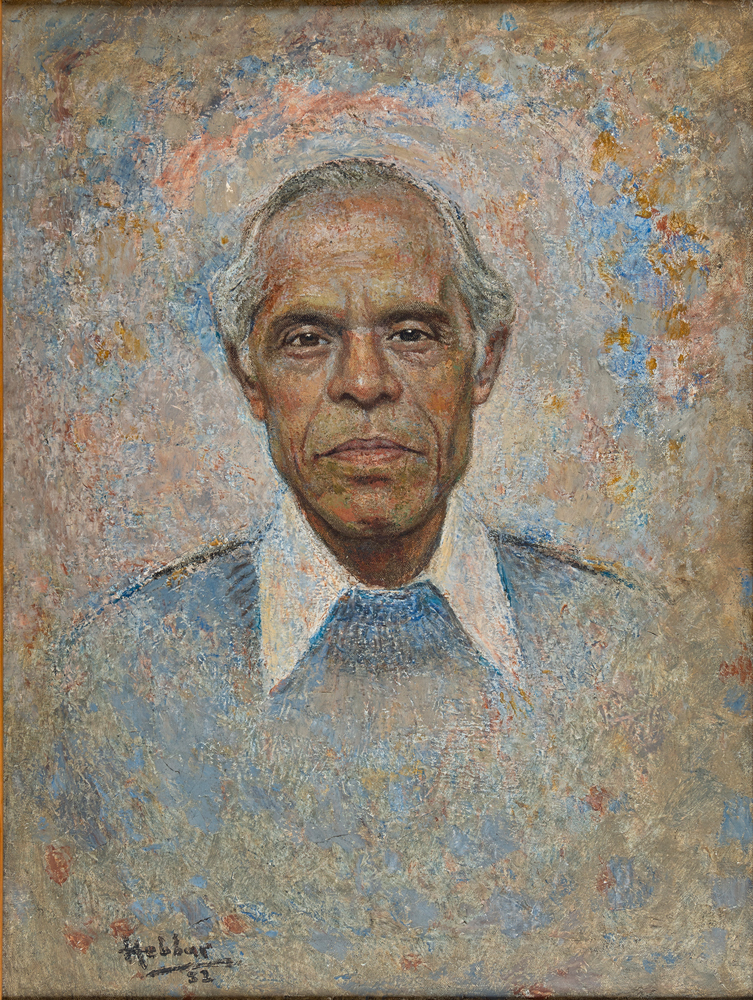

K. K. Hebbar, Untitled (Portrait of S. A. Krishnan), 1982, Oil on canvas, 24.0 x 18.0 in. Collection: DAG |

Hebbar’s 1952 portrait of the art critic and editor of the ‘Lalit Kala Contemporary’ series, S. A. Krishnan shows the proximity that artists maintained with art critics, who were equally shaping the narrative of an emergent Indian modernism. Therefore, individualism and collectivism both found expression in these works, deviating from the mythological and religious themes that governed the visual idioms of the Bombay school for many decades preceding this time—leading to a progressive drive for modern art to seamlessly fit the category of political art as well. It was in the intertwining of both that the modern acquired its unique dimension in India.

K. K. Hebbar, Untitled (Study for CIBA Mural), Gouache on paper, 5.2 x 10.5 in. Collection: DAG