Unpacking Indian Modern Art: Not a Survey Course

Unpacking Indian Modern Art: Not a Survey Course

Unpacking Indian Modern Art: Not a Survey Course

Grasping the full complexity of ‘seeing’ may well be an immense undertaking—one perhaps best suited to the realm of conjecture. Yet, even if the ultimate aims of such a pursuit remain elusive, exploring the meaning and reach of seeing as a critical exercise—rather than accepting it as a passive, everyday act—is a worthwhile endeavour.

In an era marked by a relentless flood of images that provoke both anxiety and euphoria before quickly fading into visual noise, an intermedial approach offers valuable pedagogical potential. It can help illuminate the relationships and tensions between various expressive forms. Incorporating such strategies into arts education, in particular, can foster a sustained dialogue between the complex bundles of image, text, and sound that we analyse, and what art historian W. J. T. Mitchell refers to as the ‘vernacular visuality of everyday seeing.’

|

Anonymous, Untitled (Hanuman Battling Ravana), Hand-tinted woodcut on paper, 15.2 x 10.0 in. Collection: DAG |

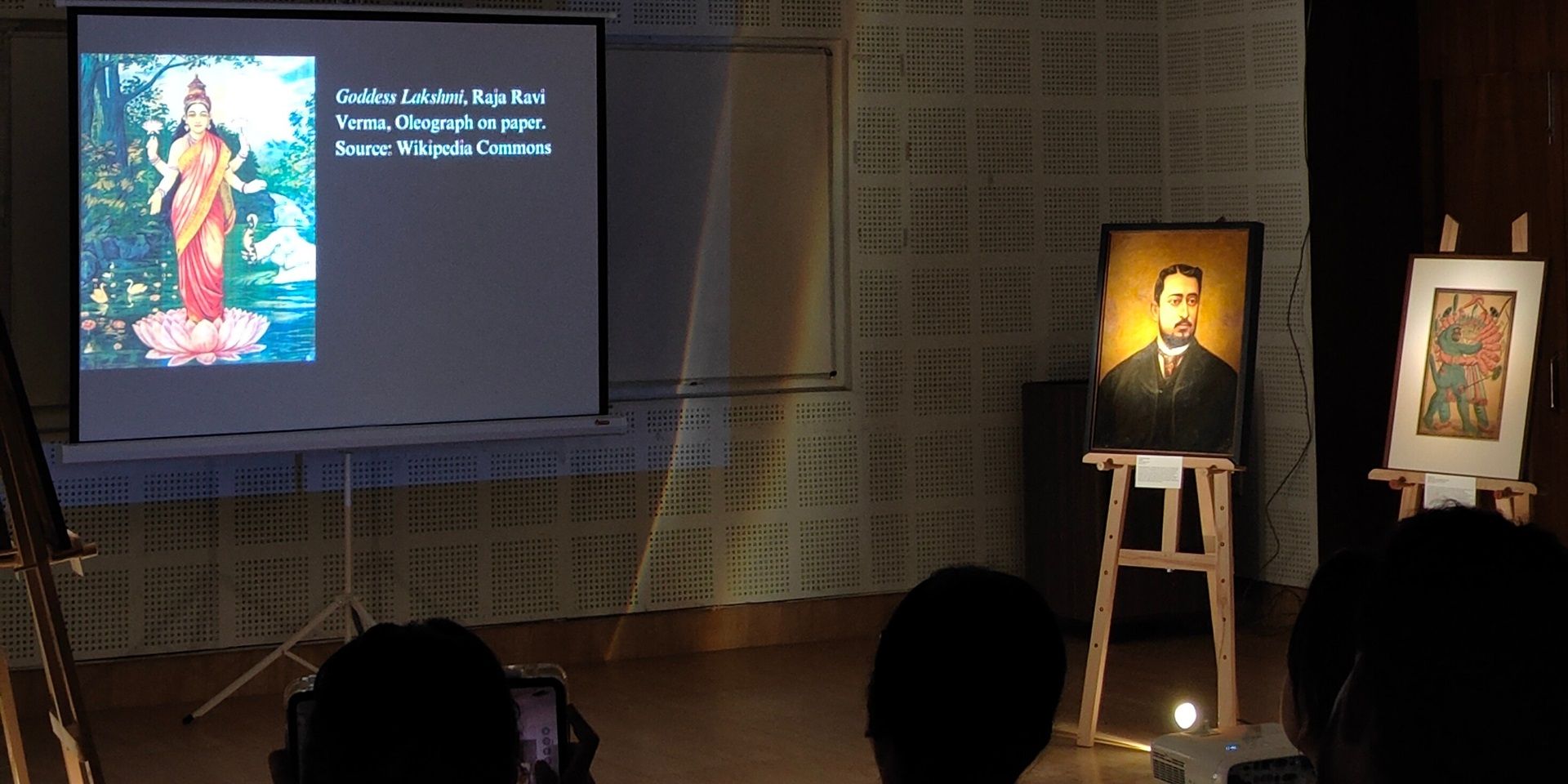

As a part of DAG Museums’ latest art-integrated educational initiative, ‘Unpacking Indian Modern Art: Not a Survey Course’, we took an original set of artworks from the DAG Collection to university classrooms to encourage a critical and contextual reading of works of art. Through a mix of lectures centered on specific artworks exemplifying dominant trends of late nineteenth and early twentieth century Indian art, workshops on ‘close looking’ and curation, and a visit to the Indian Museum, we explored theories and approaches to modern art with undergraduate humanities students of Jadavpur University. One of our primary objectives was to familiarise students with art historical methods of engaging with the multiple contexts of production, including a close study of their medium, form, and other visual codes. As a final outcome of the sixteen-hour course, students curated artworks from the DAG and other digitised collections with critical narrative and textual intervention in the form of short videos. Riddhima Koley, a second-year student of the department of English who had signed up for ‘Unpacking Indian Modern Art’ tells us that, ‘What really excited me about this course was the privilege of engaging with original artworks—it made the whole experience come alive. The course gave me a first-hand look at the world of art curation through a final curatorial project, which furthered my interest in how to portray and interpret stories through curation. Along the way, I developed a deeper understanding of Indian modern art, broadly Indian art forms, and modern art pedagogy, especially how to read and interpret art in new ways.’

|

Sunayani Devi, Untitled, Water colour on cardboard, 14.2 x 9.5 in. Collection: DAG

|

In recent years, the introduction of courses approaching intermediality through a study of literature and other arts in Humanities departments has led to more holistic modes of teaching the arts, despite certain territorial disciplinary anxieties. Such pedagogic shifts also meant a fresh evaluation of the formal and referential specificity of a medium, whether visual or verbal. Especially in literature departments, a thick reading of conjunctions of image and text has increasingly moved beyond comparative methods to focus on the potentially varied relationships between the visual and verbal in different modes of expression. Thus, a classroom discussion on a translation of Honoré de Balzac’s short story ‘The Hidden Masterpiece’ with reference to the 1927 edition published with etchings, engravings and line and dot drawings by Picasso, might involve investigating the rich ensemble of interactions between image and text while interpreting the complex relationship between the artist and his muse.

Dr. Sonia Sahoo, Professor of English at Jadavpur University, spoke to the editors of the DAG Journal about the relevance and limits of adopting such intermedial methodologies in university classrooms.

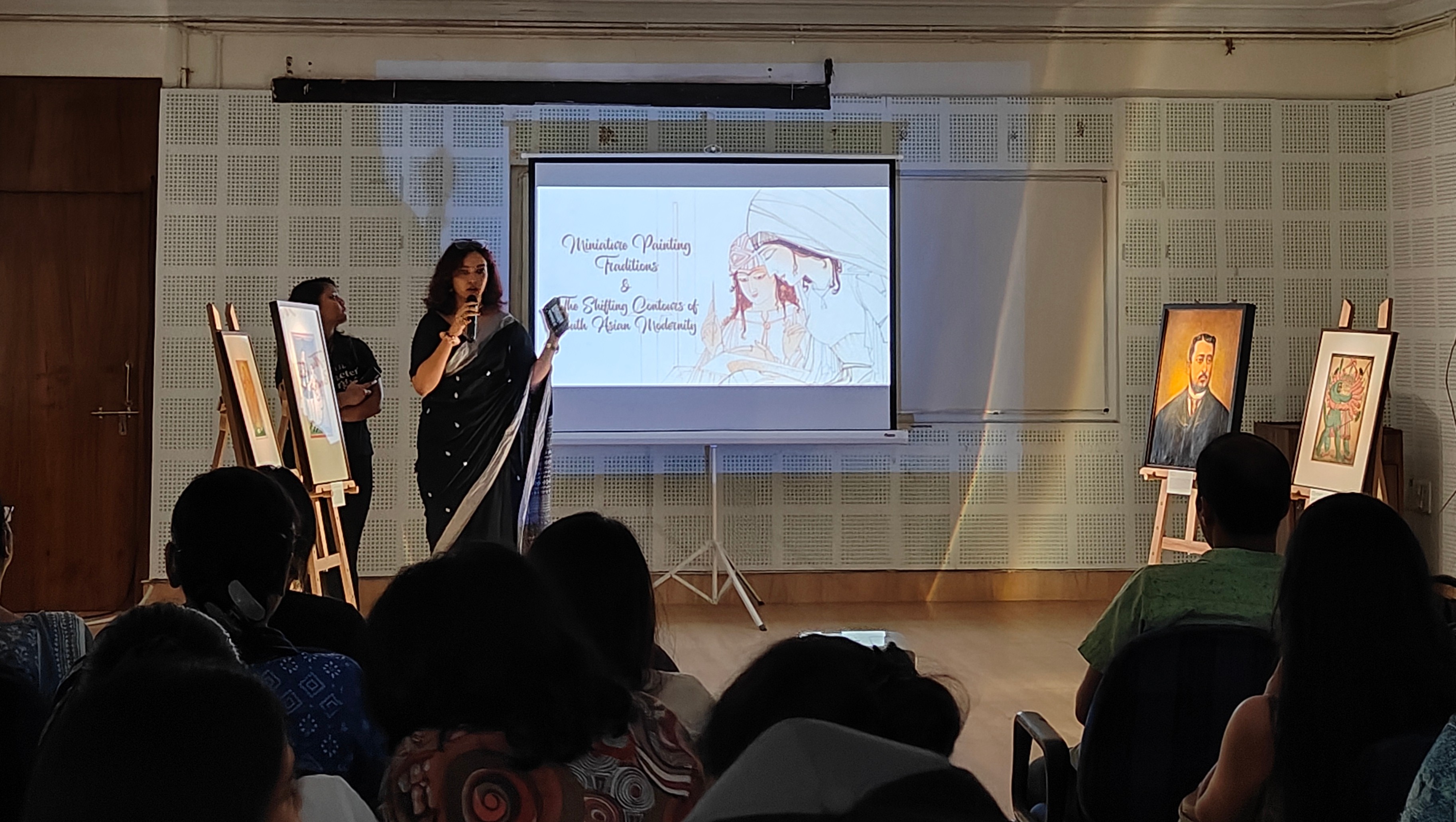

A group of workshop participants presenting their curatorial project on miniature paintings and South Asian modernism

Q. In a world where public consciousness is inundated with images proliferating across electronic and other popular media, do you think inculcating visual literacy in students should be an essential pedagogic mode in humanities and social science departments?

Dr. Sonia Sahoo: Yes, I do think it’s important. One of the ironic by-products of an image-saturated world is not just an unnecessary sensorial overload but a lack of critical engagement and diminished appreciation of visual content. Ideally, one would have expected the opposite to happen. So, it is vital that students be made ‘visually literate’ which implies the critical ability to read, understand, and (de)construct meanings of images and visual media. I would say that focusing on visual codes, or in fact specific codes of any medium, will allow students to imbibe interpretive skills and abilities to make connections across mediums of expression that facilitate meaning-making.

|

M. A. R. Chughtai, Untitled, Watercolour on handmade paper, 21.5 x 14.5 in. Collection: DAG

|

Q. Do you feel that the increasing academic emphasis on the materiality of a text and its context of production and circulation in the wake of the cultural turn in humanities opens up new ways of unpacking what W. J. T. Mitchell calls ‘the tantalizing affinity and tension between verbal and visual art’? Have you found intermedial studies to be a useful tool in unpacking such interplays between the two mediums in your own teaching experience?

Sahoo: Understanding the text as a material commodity is to engage with the synergy of verbal and visual elements that together constitute the text. Of course, when we read a text, our perception of it is coloured by its visual form and its material signifiers. I recall how Prof. Ananda Lal used to point out how reading dramatic texts without an understanding of their performative context amounted to an incomplete understanding of theatre and its materiality. Intermediality does offer a new approach to explore and critically compare the relationship between text and image, though in my opinion literary studies has always been far more receptive to an understanding of the visual-verbal materiality of texts than other disciplines. Unfortunately, the earlier decades of the twentieth century had largely adopted a blinkered approach towards materiality or the visible or tangible aspects of the text by relegating it to fine arts departments or specialised disciplines such as book history rather than actively reworking them into literature departments. My own pedagogical approach has always been oriented towards incorporating visual elements into an understanding of literary texts, wherever feasible. One particular text that has proved a perennial favourite of mine in unpacking this interplay is Laurence Sterne’s Tristram Shandy (1759-1767) where the written text continually tries to approximate to or appropriate the status of a visual signifier through its incorporation of quirky typographical markers and visual paraphernalia such as marbled, blackened or blank pages—something quite likely in a period where a) the transition from an oral or aural culture to the silent world of print was underway and b) the interface between the verbal and the visual was epitomised in the Lockean idea of the tabula rasa, the mind conceived as a blank canvas or sheet that allows itself it to be written upon via sensory impressions of the external world.

|

Students spoke about the impact of bringing original works and prints to the workshop sessions |

Q. I remember attending the classes you took on reading European Baroque art vis-à-vis metaphysical poetry, and coming away with an enriched understanding of the period through important interactions between visual and verbal codes. Would you say that the recent New Education Policy (NEP 2020) and the corresponding shifts in education policies with an emphasis on interdisciplinarity necessarily increases the scope for such dialogues within classroom teaching in an English Literature department?

Sahoo: The N. E. P. has definitely widened the ambit of this interdisciplinary dialogue, though our department has been offering a wide array of core and optional courses as part of the undergraduate (C. B. C. S.) and postgraduate curriculum over the years, much before this recent shift in educational policy. These would include courses such as Literature and the Other Arts, Romanticism: Verbal and Visual, Literature and the Visual Arts, Image and Text, and Introduction to Renaissance Art, to name a few. Yes, I do recall that I read Henry Vaughan vis-à-vis the European Baroque art because I felt it might be interesting to see how his work was a response to larger visual/aesthetic movements of the times. There has always been some reluctance towards the incorporation of visual media in ‘traditional’ bastions such as literature in particular, or the humanities in general, that perceive intermedial pedagogic techniques as largely marginal at best or irrelevant at worst. However, I believe our department has been far more eclectic and cosmopolitan in its approach to what we term as a literary text much before the N. E. P. came into place.

|

A student from the audience studying the Bamapada oil portrait on display on the day of the student presentations at Jadavpur University |

Q. I just wanted to return to something we talked about earlier—the lack of critical engagement with Indian art among students. That was really the starting point for us thinking about a course like Unpacking Indian Modern Art. It’s interesting that this gap still exists, especially when you consider how many English Literature departments in India—Jadavpur being a prime example—have already been pushing beyond traditional boundaries. They’ve brought in courses on vernacular literature in translation, Literature and the Other Arts, visual studies, and more. So, with all these efforts to get students thinking critically about a wide range of cultural texts, why do you think the disconnect with Indian art still lingers?

Sahoo: This is an interesting question. Our department has indeed been at the forefront with regard to cutting-edge courses that move beyond the mainstream disciplinary parameters to engage with what might be considered to lie in the ‘peripheries’ of the literary ‘canon’. However, Indian art and aesthetics does not feature too exclusively in the curriculum despite the major thrust on Indian Writing in English, Postcolonial Literatures or Literary Theories for that matter. Maybe it has more to do with a mindset that still perceives Indian Art as an exotic relic of the golden past rather than as a form of praxis that can be used to engage with Indian and world literature. This is one of the reasons why we planned to host a workshop that focused on the interpretive tools or strategies required to enable the students to understand the conceptions of ‘modern’ in Indian Art and not simply confine it to the realm of colonial conceptions of the strange and the beautiful.

|

Bamapada Banerjee, Untitled, Oil on canvas, 25.0 x 19.0 in. Collection: DAG

|

Q. Have you or the department been offering any recent courses which explore the intermedial arena of contextual interpretation in the arts, to help students engage further with the meaning-making process in an age of information?

Sahoo: I always try as far as possible to incorporate visual elements in my teaching. The written or printed word is probably undergoing a slow demise, and we are now aware that the term ‘text’ subsumes within itself a wide range of old and newer media such as films, television, dance, photographs, graphic novels, blogs, advertisements, podcasts, videogames, visual arts (‘high’ and ‘low’) comprising both moving and static images or bundles of image-text-audio. While teaching Old Attic Drama as part of my course on Classical and Medieval Literature I usually show visuals of vase paintings, sculptural reliefs, and architectural remains as a means of visual contextualisation. When I taught Ovid’s Metamorphoses last semester, I made use of paintings centered around particular myths to see how far the visual portrayal amplified or reduced the resonances found in the primary narrative and to explore adaptations or translations across media. Arguably, this is just not an attempt at making my lectures interesting but also to see how far powerful narratives can be shaped not just through words but images as well.

At a time when the whole idea of disciplinary borders is breaking down, I am glad that the DAG workshop has allowed a hands-on understanding of how inter-disciplinary art-historical methods can open new vistas of understanding and add significantly to our engagement with any text.