|

Travel With Us Travelling with artistsAnkan Kazi July 01, 2023 How have artists represented the activity of travelling in the mountains? Before commercial tourism became a rage, people travelled for a variety of reasons—even though religious pilgrimages tracing sacred geographies was high on the list of reasons for travelling in the Himalayas, which contain some of the holiest mountains, especially for the Hindu and Buddhist traditions. Mountains were also technological frontiers when it came to innovations in travel. In Indra Dugar’s painting we see a bridal procession, ranged against an exquisite, fecund landscape of spring, with a glimpse of the peaks of a temple complex on the other side of the hill. |

Indra Dugar

The Bride's Journey

Tempera on Nepali paper

Collection: DAG

|

Means of Travel Litters, palanquins and basket-chairs were popular modes of transportation for the ruling and socio-economic elite, especially before the arrival of the railways in the late-nineteenth century. Litters were wheelless vehicles, a type of human-powered transport, for carrying people. They were often used for longer journeys and required bearers to carry them on their shoulders. Litters could take the form of open chairs or larger, covered palanquins with silk covers, with some taking the form of a miniature hut. Sedan chairs were also used, which were closed litters for one passenger. These modes of transportation were used by British residents too, including sportsmen, in colonial India to signify a symbolic conquest of the physical geography of India. In India, a palanquin, also known as palkhi, was a covered sedan chair, or litter carried on four poles. |

|

|

Muhammad Amir of Karraya

Thomas Holroyd reads in his palanquin

ca. 1835, 16 cm x 24 cm.

Image courtesy: Wikimedia Commons

Robert Home

Traveller in a Palanquin in India

Pen and black ink, gray ink, gray wash and graphite on moderately thick, moderately textured, beige, laid paper

Image Courtesy: Yale Center for British Art and Wikimedia Commons

Travellers had varied opinions on the nature of such means of travel. For some, it afforded much-needed leisure time when they could catch up on their reading, while for others, such as women or travelling naturalists, it was an opportunity to savour the diverse landscapes of the Indian subcontinent. Artists, in whose ranks one could include naturalists, geographers, surveyors, spies and geologists among others, made studies, sketches and records of the sights they saw—sometimes for the very first time for some western travellers like Joseph D. Hooker who probably made one of the earliest sketches of a view towards the mountain now known as ‘Everest’, after George Everest, a former Surveyor General of India (1830—1843). This mountain took over the record for the highest observed peak in the world in 1850, displacing others like Kanchenjungha and the Andean Chimborazo at the time. |

|

What were conditions of travel like in the pre-Railway days? David Arnold writes in The Tropics and the Traveling Gaze: ‘Most pre-Mutiny travel was more leisurely, averaging ten to fifteen miles a day, thus allowing for close observation of the passing countryside, coupled with frequent stops along the way, at scenic temples or in the obliging shade of mango trees. As a naturalist, Joseph Hooker, who had his first taste of palanquin travel in 1848, was rapidly convinced of the physical discomfort of traveling in a conveyance ‘horsed by men.’ ‘Then, too,’ his complaint continued, ‘you pass plants and cannot stop to gather them; trees and don’t know what they are; houses, temples, and objects strange to the traveller’s eye, and have no one to teach where and what they may be; no fellow-traveller with whom to change one curious remark.’ ' Others, by contrast, like Emma Roberts, regarded palanquin travel as providing—at least to a woman—unique opportunities to see India first-hand, to stop at and savor its remoter, more romantic, places. The best time to travel, she explained to her readers, was just after the rains, when the doors of the palanquin could be kept wide open: ‘various beauties of the jungles display themselves to view; every spot is covered with the richest verdure, and creepers of luxuriant growth, studied with myriads of stars, fling their bright festoons from tree to tree. Those beautiful little mosques and pagodas, which in every part of India embellish the landscape, look like gems as they rise from the soft green turf which surrounds them . . .’' |

|

|

M. V. Dhurandhar

Telegraph Peon

Halftone, divided back, 14.00x8.90 cm., 1904

Collection: DAG

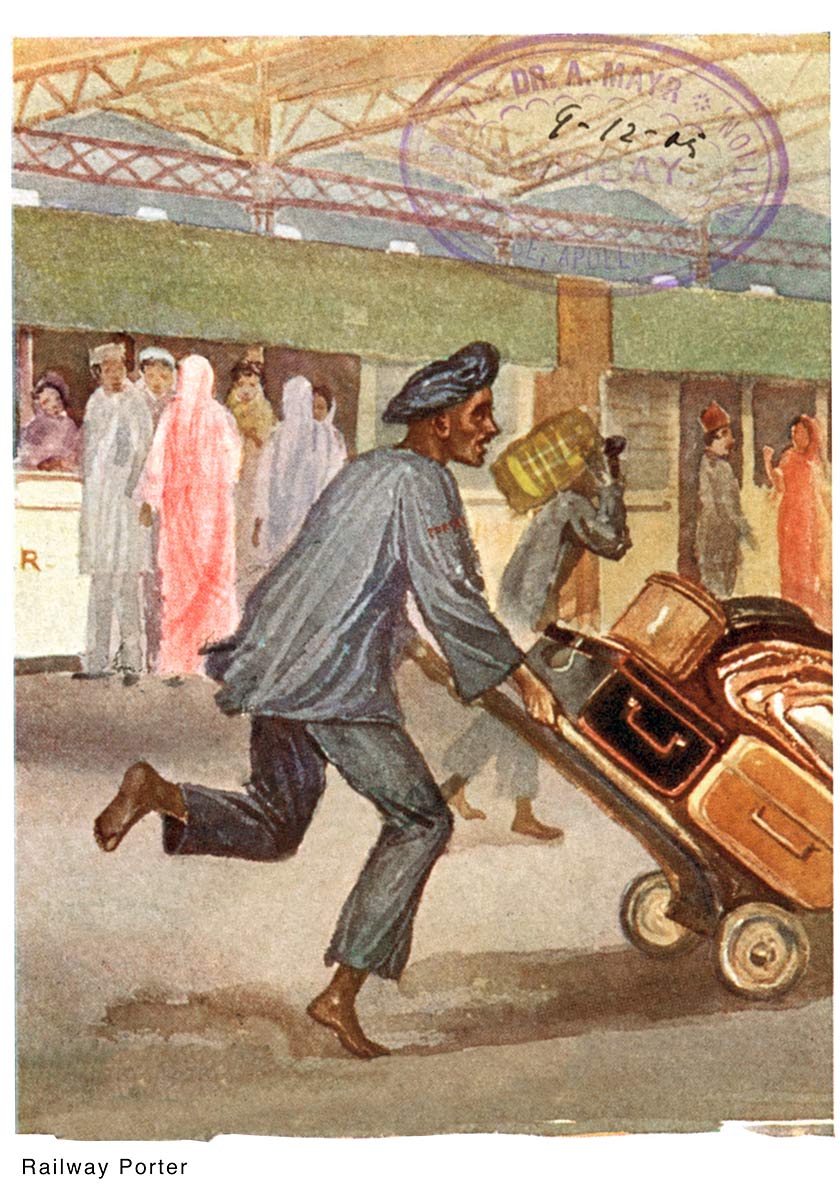

M. V. Dhurandhar

Railway porter

1905, 12.10x8.65 cm.

Image courtesy: Wikimedia Commons

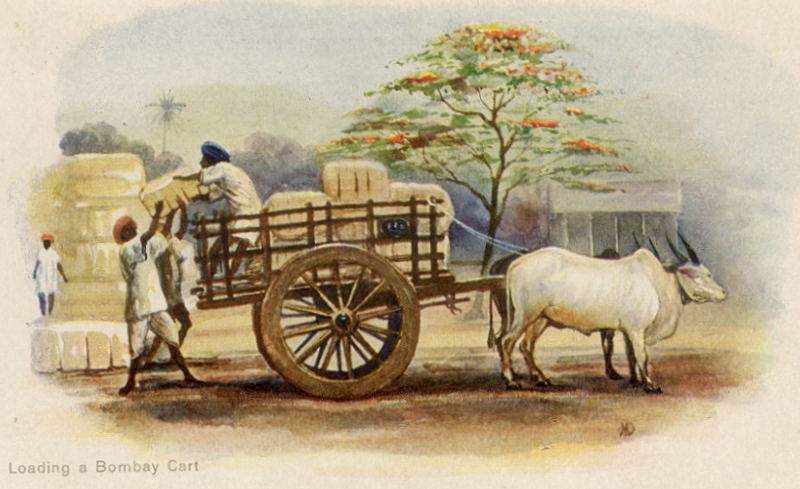

M. V. Dhurandhar

Loading a Bombay Cart

Halftone, undivided back, 14.00x8.90 cm., 1904

Collection: DAG

A Pilgrim’s ProgressM. V. Dhurandhar was one of the great academic painters of turn of the century Bombay (now Mumbai) and graduate of the J. J. School of Arts. In 1901 he met the art patron, author and publisher Sheth Purushottam Vishram Mavji. He tasked Dhurandhar with making illustrations for his periodical Suvarnamala—a work in which the artist would be engaged till 1913, allowing him to make several mythological illustrations at the time. Mavji also owned Laxmi Art Printing Press, where he was partnered briefly with D. G. ‘Dadasaheb’ Phalke, who would later go on to become a pioneer of Indian cinema. Dhurandhar made a few sets of narrative postcards for Laxmi Art Printing Press, using illustrations and storytelling. While illustrating publications on views of Bombay, he frequently showed the dynamic city on the move, featuring sketches of porters, peons and carters who were providing the labour that kept this important city of commerce and its people moving. |

M. V. Dhurandhar

Untitled (Pilgrimage of Sheth Purushottam Vishram Mavji to Vaishno Devi)

Water colour on paper, 23.4 x 34.3 cm.

Collection: DAG

M. V. Dhurandhar

Untitled (Pilgrimage of Sheth Purushottam Vishram Mavji to Vaishno Devi)

Water colour paper pasted on handmade paper, 1905, 31.0 x 22.1 cm.

Collection: DAG

M. V. Dhurandhar

Untitled (Pilgrimage of Sheth Purushottam Vishram Mavji to Vaishno Devi)

Water colour on paper pasted on mount board, 1905, 22.0 x 23.4 cm.

Collection: DAG

According to art historian Ritika Kochhar, ‘Mavji was almost a patron for Dhurandhar. In 1905, he reserved space at the grand industrial and agricultural exhibition in Mumbai to show Dhurandhar’s historical works, including those focused on Chhatrapati Shivaji Maharaj. He also commissioned Dhurandhar to paint his pilgrimage to Vaishnodevi in 1905. In this series of watercolors, one sees Mavji undertaking the pilgrimage using the traditional modes of transport such as dandi (palanquin) and Kandi (basket) as also sitting on the snow-covered road.’ In these sketches, we see Dhurandhar employing his realist style for recording the pilgrimage. |

|

The temple, located in the Trikuta Mountains in Jammu and Kashmir, has been a pilgrimage center for centuries. According to Hindu mythology, the original abode of Vaishno Devi was Ardha Kunwari, a place about halfway between Katra town and the cave. It is said that she meditated in the cave for nine months. The temple is one of the 108 Shakti Peethas dedicated to Durga, who is worshipped as Vaishno Devi. Today, pilgrims travel from the city of Jammu to the village of Katra, which is well connected by helicopter, rail, and road. In the early 1900s, the journey would have been much more difficult and time-consuming. However, the spiritual significance of the pilgrimage would have been just as strong, if not stronger, as it is today. As we can see from Dhurandhar’s record of Mavji’s journey, however, the pilgrim had much help from a train of porters and bearers even as he posed imperiously for the artist’s sketches. |

|

M. V Dhurandhar Shrimant Balasaheb Maharaj (detail) Oil on canvas, 48.0 x 69.0 cm. Collection: Directorate of Archaeology and Museums, Government of Maharashtra (Shri Bhavani Museum and Library, Aundh, Satara) |

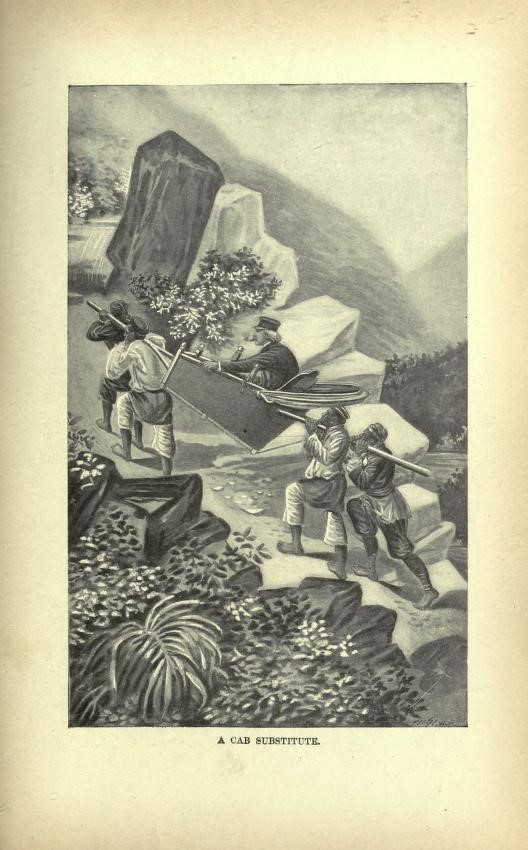

From Mark Twain's Following the Equator

A cab substitute

Image courtesy: archive.org

The Museum on the Mountain: Following Mark TwainMark Twain's Following the Equator (1897) is a travelogue that narrates his experiences during his lecture tour across the Indian subcontinent, Australia, and South Africa in 1895-96, about a decade before Dhurandhar and Mavji were travelling to the Himalayas from the western part of the subcontinent. The book is a mix of Twain's personal responses to people and cultural practices in India, his observations of the British Empire, and the transnational connections he made between slavery at home and European imperialism around the globe. However, Twain's travelogue is replete with ideologically contradictory statements, which was largely common even among accounts left by travellers who tended to be more sympathetic with the colonized people than the colonizers. Twain’s account alternated between respect for native cultures and a typical nineteenth-century assertion of the superiority of Anglo-American civilization. |

|

The book is also known for its humorous anecdotes and satirical style, which are characteristic of Twain's writing. Here is what he had to write about his trip to Darjeeling: ‘Some time during the forenoon, approaching the mountains, we changed from the regular train to one composed of little canvas-sheltered cars that skimmed along within a foot of the ground and seemed to be going fifty miles an hour when they were really making about twenty. Each car had seating capacity for half-a-dozen persons; and when the curtains were up one was substantially out of doors, and could see everywhere, and get all the breeze, and be luxuriously comfortable. It was not a pleasure excursion in name only, but in fact. After a while we stopped at a little wooden coop of a station just within the curtain of the sombre jungle, a place with a deep and dense forest of great trees and scrub and vines all about it. The royal Bengal tiger is in great force there, and is very bold and unconventional. From this lonely little station a message once went to the railway manager in Calcutta: “Tiger eating station-master on front porch; telegraph instructions.”’ After stopping for a brief hunting expedition, he writes, ‘The railway journey up the mountain is forty miles, and it takes eight hours to make it. It is so wild and interesting and exciting and enchanting that it ought to take a week. As for the vegetation, it is a museum. The jungle seemed to contain samples of every rare and curious tree and bush that we had ever seen or heard of. It is from that museum, I think, that the globe must have been supplied with the trees and vines and shrubs that it holds precious. |

|

Walter F. Brown The Alpine Litter from Mark Twain's A Tramp Abroad (1880) Image courtesy: Wikimedia Commons |

|

Elsewhere he gives us another anxiety-inducing account of travelling downhill on a ‘handcar’ that was attached to the railway tracks, followed by a train: ‘We traveled up hill by the regular train five miles to the summit, then changed to a little canvas-canopied hand-car for the 35-mile descent. It was the size of a sleigh, it had six seats and was so low that it seemed to rest on the ground. It had no engine or other propelling power, and needed none to help it fly down those steep inclines. It only needed a strong brake, to modify its flight, and it had that. There was a story of a disastrous trip made down the mountain once in this little car by the Lieutenant-Governor of Bengal, when the car jumped the track and threw its passengers over a precipice. It was not true, but the story had value for me, for it made me nervous, and nervousness wakes a person up and makes him alive and alert, and heightens the thrill of a new and doubtful experience. The car could really jump the track, of course; a pebble on the track, placed there by either accident or malice, at a sharp curve where one might strike it before the eye could discover it, could derail the car and fling it down into India; and the fact that the lieutenant-governor had escaped was no proof that I would have the same luck. And standing there, looking down upon the Indian Empire from the airy altitude of 7,000 feet, it seemed unpleasantly far, dangerously far, to be flung from a handcar. Everything looked safe. Indeed, there was but one questionable detail left: the regular train was to follow us as soon as we should start, and it might run over us. Privately, I thought it would.’ (Mark Twain, Following the Equator) |

|

Mark TWain Image courtesy: Wikimedia Commons |

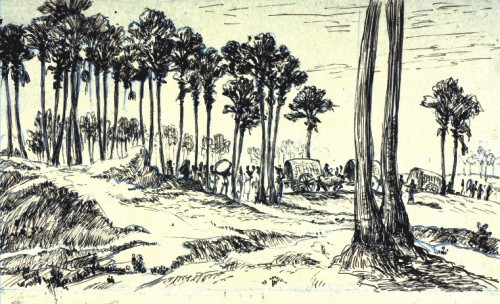

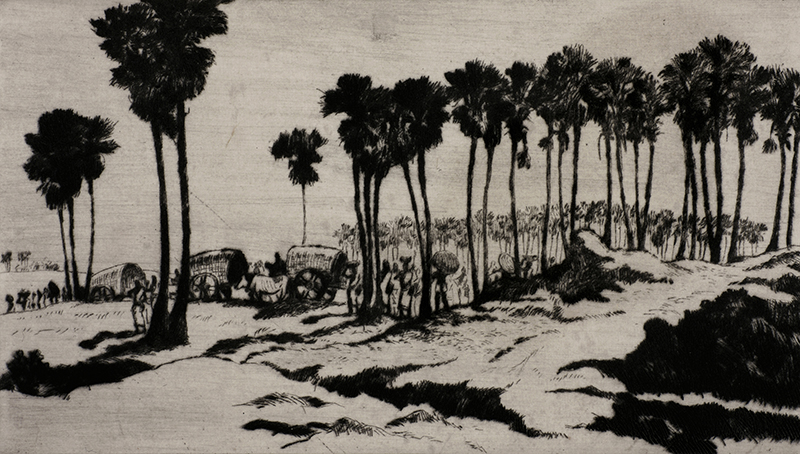

Safiuddin Ahmed

Views of Santiniketan

Pen and Ink, 1945

Image courtesy: Wikimedia Commons

Safiuddin Ahmed

Views of Santiniketan

Pen and Ink, 1945

Image courtesy: Wikimedia Commons

From Santiniketan to NepalAfter finishing an ambitious, eighty-feet long mural featuring the lives of the Medieval Saint Poets of India on the walls of the Hindi Bhavana in Santiniketan around 1947, Benode Behari Mukherjee was looking to move on from the place that had shaped his identity as an artist for over two decades. He wrote to the Foreign Minister to the Nepal Government, Narendramani Acharya, and secured a job as a curator in the country’s Education Department. He resigned his job at Kala Bhavana and ‘(o)ne evening… left for Nepal, leaving my worldly belongings with two friends and snapping my sentimental ties with Santiniketan.’ |

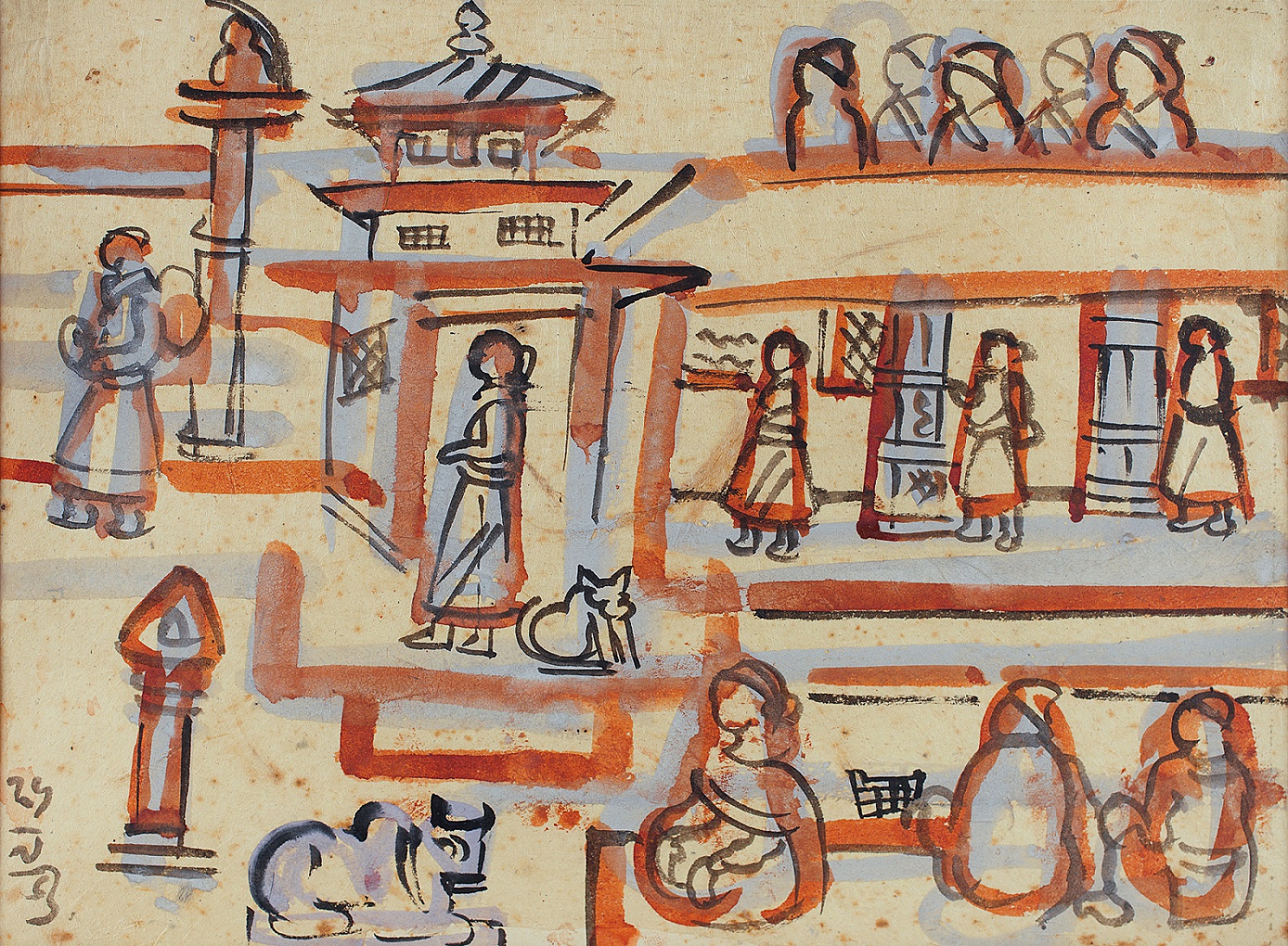

Benode Behari Mukherjee

Untitled

Watercolour and ink on paper, 40.6 x 51.3 cm.

Collection: DAG

He describes his arduous travels thus: ‘Nowadays you can fly to Nepal from any part of India. But I went by the difficult mountainous road. My sketchbooks probably have some record of this road… What comes readily to mind is the astounding majesty of the Himalayas. Travelling on this road one constantly felt how small, insignificant and helpless man is, however bloated he may be with his ego. The memory of my past was also blurring away under the impact of the road. Carrying me in a basket-chair on their shoulders, the coolies started in the morning and reached me by evening to the government guest house at Chisagadi. Starting off next morning, after eating fish and rice at the coolie camp, they came and paused before the Chandragiri Mountain. Then crossing the Chandragiri Mountain we reached Thankhot towards evening. At Thankhot they put down the basket-chair on the level ground and shouted in chorus ‘Jay Pashupatinath.’’ (Chitrakar, Benode Behari Mukherjee) |

|

Benode Behari had ample time to wander around the streets of Kathmandu, the capital city, observing its temple architecture, its people and associating with friends and fellow-artists like Chandraman Maske, who knew the Bengali language due to his stint at the ‘Calcutta Art School’. Due to his struggles with vision, he was largely reliant on the help of porters and bearers. If the physical impact of mountainous terrain made an impression on Benode Behari’s mind earlier, the sacred circumambulations of the people anchored his idea of Nepal—and the Newari people especially—to the country’s religious architecture. ‘During the seven days of holidays I wandered about the town with the bearers. There was gambling going on, on both sides of the streets. Everywhere there were stupas of various shapes and sizes which people went round and round. Chandraman took me ff the hands of the bearers and said, ‘Come, let me show you around.’ (Chitrakar, Benode Behari Mukherjee) |

|

|

Benode Behari Mukherjee

Nepal

Water colour and ink on cardboard

Collection: DAG

Chandragiri Hills, Thankot (Nepal)

Image courtesy: Wikimedia Commons

Pashupatinath Temple, Kathmandu (Nepal)

Image courtesy: Wikimedia Commons

Chandraman was crucial in guiding Mukherjee around these streets and identifying the unique architectural heritage of Kathmandu, which would aid the latter artist in his own depictions of the temple complexes of the city. ‘I should admit,’ Mukherjee writes, ‘that Chandraman knew his Kathmandu well—which temple had good wood sculpture, which had metal icons, where the prasad was good; these were at his fingertips. Once could sketch here standing on the road side, people did not act curious. If any youngster edged up to me to see what I was doing the grownups said, ‘Artist. Come away from there.’ His stay at Nepal allowed him to absorb and exchange artistic knowledge with members from local artisanal communities as well—from which sprung its great temple architects, wood and stone carvers and sculptors. Kulasundar Shilakarmi is one such ‘eminent Nepalese artisan’ that Mukherjee wrote about meeting, and we also know that the designer Riten Mozumdar trained under him a few years later. |

|

Many Indian artists depicted travel scenes across the many mountainous regions of South Asia. From academic artists like Dhurandhar, Abalal Rahiman, J. P. Gangooly and his students, such as Kisory Roy, to those who worked largely in the post-independent era, such as Sunil Das or K. C. S. Paniker, depicting travel and movement in general became a great mode of experimentation. Indra Dugar was another artist known for his extensive travels across the Indian subcontinent. He painted several plein air views, often depicting travelers, pilgrims or processions making their way across difficult but fulsome landscapes. In this work he paints a view of Rajgir in the state of Bihar, associated historically with Buddhism and Jainism; and once again includes a train of travellers, giving the landscape a sense of movement and being lived-in, instead of the desolation championed by the colonial picturesque aesthetic. With the advent of quicker modes of travel, most mountainous areas are now easily reachable by trains, aeroplanes or automobiles. Does this encourage a new way of looking at the scenery unfolding around us? What are some of your favourite depictions of mountain travel by artists? |

|

Indra Dugar A Raja Griha Landscape Tempera on tussar silk pasted on paper, 11.7 x 23.7 in., 1953 Collection: DAG |