Translating the Modern: A Walk Around Santiniketan, Part II

Translating the Modern: A Walk Around Santiniketan, Part II

Translating the Modern: A Walk Around Santiniketan, Part II

collection stories

Translating the Modern: A Walk Around Santiniketan, Part IIChaiti Nath The City as a Museum, Kolkata 2025’s tribute to the innovations in Bengal Architecture begins with a series of programmes exploring the unique architectural and cultural sites of Santiniketan. We approach them not as static monuments and sites but as living, evolving experiments, in the second and final part of our story. |

Chittaprosad

Terracotta from Bengal (detail)

1955, 7.0 x 3.2 in.

Collection: DAG

|

|

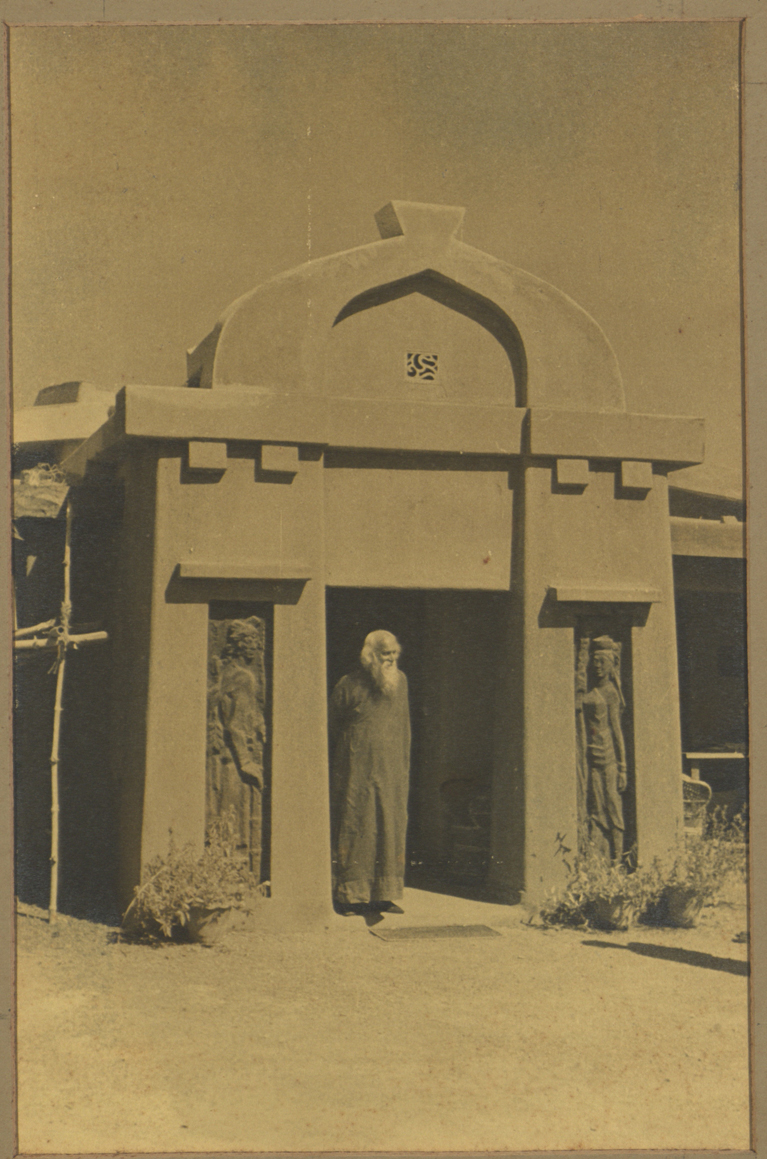

Tagore in Shyamali

Collection: Rabindra Bhavana, Visva Bharati

Shaymali, Photographed in 2025

Detail of Shaymali, Photographed in 2025

Lala Deen Dayal

Ajanta. Cave no. 19 (From the album 'Views of H. H. the Nizam's Dominions, Hyderabad Deccan (1888), 10.5 x 8.0 in.

Collection: DAG

In a spirit of experimental revivalism, within the Uttarayan complex Santiniketan’s architect and design team turned to the enduring prototype of the Buddhist chaitya hall, akin to those at Ajanta and Bagh. This exploration culminated in Shyamali (The dark one, 1935), a name derived from its construction from locally sourced mud, with the earlier Chaitya (Chaiti) serving as its direct pilot project. Its frontal façade and structural plan faithfully echo the chaitya form, characterized by a solid mass with few openings. The surface is animated by numerous relief sculptural panels by Ramkinkar Baij and Nandalal Bose. Tagore, anticipating his own death due to constant ill health, conceived this house to be his final resting place. The poet wrote to Amiya Chakravarti:

|

Exploratory Murals on the Black house, Kala Bhavana, photographed in 2025

Rabin Halder

Ajanta

1977, Oil on canvas 16.0 x 20.0 in.

Collection: DAG

In residencies like Shyamali and Kalo Bari, the modern pursuit of an indigenous identity finds profound purpose. It does not merely imitate a historical form but re-interprets it through local materials and contemporary artistic practice. This is the very essence of what scholar R. Sivakumar termed Santiniketan’s ‘contextual modernism’—where modernity becomes a unique stylistic grammar grounded in the immediate environmental context and resonates with centuries-old global and local traditions. |

|

|

Sambhu Saha

Tagore framed in the verandah of Punascha

Collection: Rabindra Bhavana, Visva Bharati

'Punascha’, within the Uttarayan complex, photographed in 2025

Tagore’s ‘architectural postscript’, Punascha (1936), is a small house distinguished by its southern, roofless, yet enclosed semi-circular patio. The wall of the core room extends outward, its roof sloping down to form a low veranda parapet that defines a unique, open-air room—a room without a roof. |

'Udichi’, inside Uttarayan complex, photographed in 2025

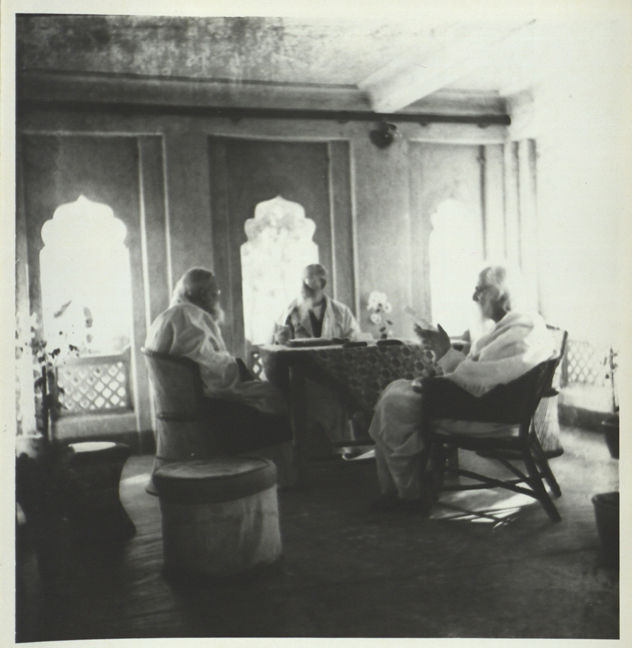

Sambhu Saha

Rabindranath with C. F. Andrews and Ramananda Chatterjee at Udichi

Collection: Rabindra Bhavana, Visva Bharati

The final house that was created within the Uttarayan complex was Udichi (The Ascendant, 1938) whose first floor can only be accessed by a staircase with lattice railings that dramatically enhances the ‘act of going up’ by the exterior of the house. The windows are designed after foliated Mughal arches, and Jalis adorn the railings. Sanyal draws a compelling parallel between Udichi and Le Corbusier's Villa Savoye, noting their shared principle of elevation on pilotis (Udichi was originally built on four short columns). This conceptual resonance is historically grounded in Tagore's 1930 visit to Paris, as suggested by Saptarshi Sanyal, where he exhibited his paintings while Corbusier's modernist icon was under construction, suggesting a plausible conduit for this avant-garde architectural idea. |

|

Continuing Pedagogical Impact The terracotta temples of Birbhum and Purba Bardhaman exerted a continuing pedagogical influence through their vivid narrative scenes. Their synthesis of village life, use of locally sourced materials, the collaborative spirit evident in their construction, and the temperament of borrowing from immediate cultures deeply aligned with the academic attitude of Kala Bhavana. Inspired by this, artists from Santiniketan and their contemporaries integrated these compositional formats into their practice. They adopted both the visual motifs and the artisanal methods to create new works that celebrated India’s rooted heritage. These visits to the temples for sketching and study became an essential, if informal, part of their artistic training tradition that continues today in the form of excursions and cycle trips. |

|

|

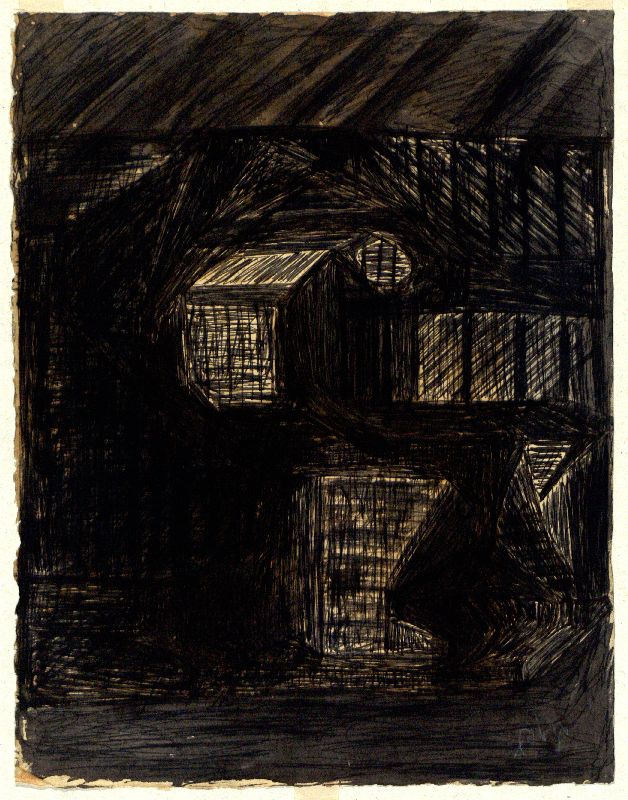

Rabindranath Tagore

Architectural form

Blue, black ink used with pen on paper, 20.2 x 26 cm.

Collection: Rabindra Bhavana, Visva Bharati

Ramendranath Chakravorty

Chattimtala, Santiniketan

1931, 3.2 x 5.0 in.

Collection: DAG

Santiniketan’s new UNESCO status brings a distinct risk that architectural historian Saptarshi Sanyal calls the erosion of its 'multi-scalar spatial imagination'—the poet’s nurturing 'nest' hardening into a fixed 'property.' Visva-Bharati’s university designation in 1951 had already set this shift in motion. A similar tension shapes the terracotta temples of greater Birbhum. Dilapidated, repainted, or sustained through community care, these temples risk being severed from the vibrant bazaars and livelihoods that form their living environment once formal heritage accreditation arrives. An attentive, inclusive reading of these sites is now essential—only such engagement can protect their ideological and cultural integrity from a model of preservation that freezes rather than renews, turning heritage into a monument rather than a living tradition. |

|

References

|

|

|