Totems of the Everyday: Madhvi Parekh's Anthropological Art

Totems of the Everyday: Madhvi Parekh's Anthropological Art

Totems of the Everyday: Madhvi Parekh's Anthropological Art

Madhvi Parekh, Man with Serpent (detail), 1993, Watercolour on paper laid on mount board, 12.2 x 16.2 in. Collection: DAG

Totems are symbolic objects, animals, plants, or other natural entities that help structure relationships within a society. They have long attracted the interest of scholars and anthropologists, particularly in contexts beyond Western social frameworks, where totems serve as organising principles in various Indigenous or remote societies.

They can mark identity, lineage, or social roles, and often carry spiritual, cultural, or cognitive significance. In anthropology, totems are not merely decorative or objects of worship: they serve as conceptual tools, helping humans organise relationships, make sense of the natural world, and reflect on social and cultural structures.

|

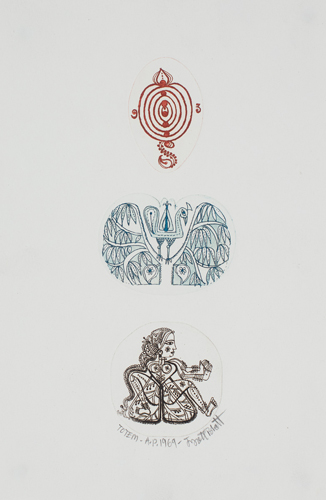

Jyoti Bhatt, Totem, 1969, Etching on paper, 7.7 x 2.7 in. Collection: DAG |

The French anthropologist Claude Lévi-Strauss, in his 1962 book Totemism, wrote that ‘animals are good to think with’. For Lévi-Strauss, totemism was never a quaint superstition; it was a sophisticated grammar of relationships—a way of making the world intelligible through analogy and symbolic thought. Totems, he argued, are not merely objects of reverence; they are tools for thinking, used to explore and make sense of human existence. They act as bridges between the visible and the invisible, transforming the natural world into a symbolic language through which people reflect on themselves and their place in the world.

|

Madhvi Parekh, Untitled, 1996, Poster colour on paper, 9.5 x 6.7 in. Collection: DAG |

It is within this Lévi-Straussian symbolic economy that Madhvi Parekh’s art unfolds. When one encounters her recurring birds, fish, eyes, ladders, serpents, tables, and maternal figures, it becomes clear that these motifs are not decorative but cognitive: small, persistent signs that allow her to think with the world and reflect on relationships, memory, and transformation. Engaging with the vocabulary of anthropology became a strong substratum of Indian artistic practice in the mid-twentieth century, especially in the decades after independence, as artists sought to incorporate idioms, concepts and forms from India’s rich repository of folk and ‘indigenous’ art. This was also enabled by the work of scholars and artists ranging from Verrier Elwin and Sunil Janah to Jyoti Bhatt, who documented their lifestyles and artforms. The central problem was articulating a relational aesthetic that connected the concerns of modernists who took inspiration from around the world with that of indigenous forms, to craft a new, ‘national’ style.

|

Madhvi Parekh, Landscape I, 1998, Acrylic on canvas, 36.0 x 24.0 in. Collection: DAG |

Parekh explains:

‘Gods and human beings and animals and birds are all the same, and every object in our life shares a relationship with us, so I create works that contain these stories—my stories, your stories. And I paint exactly as I like.’

For Lévi-Strauss, totems mediated between humans, the natural world, and symbolic logic. Invoking an anthropological lens allows us to see Parekh’s work not merely as visual art, but as attempts to formulate a language of cognitive engagement—an inquiry into relationships, memory, and transformation. Through this perspective, her drawings and paintings become sites where the everyday intersects with the sacred, revealing how symbolic forms can articulate human experience and reconfigure social hierarchies.

|

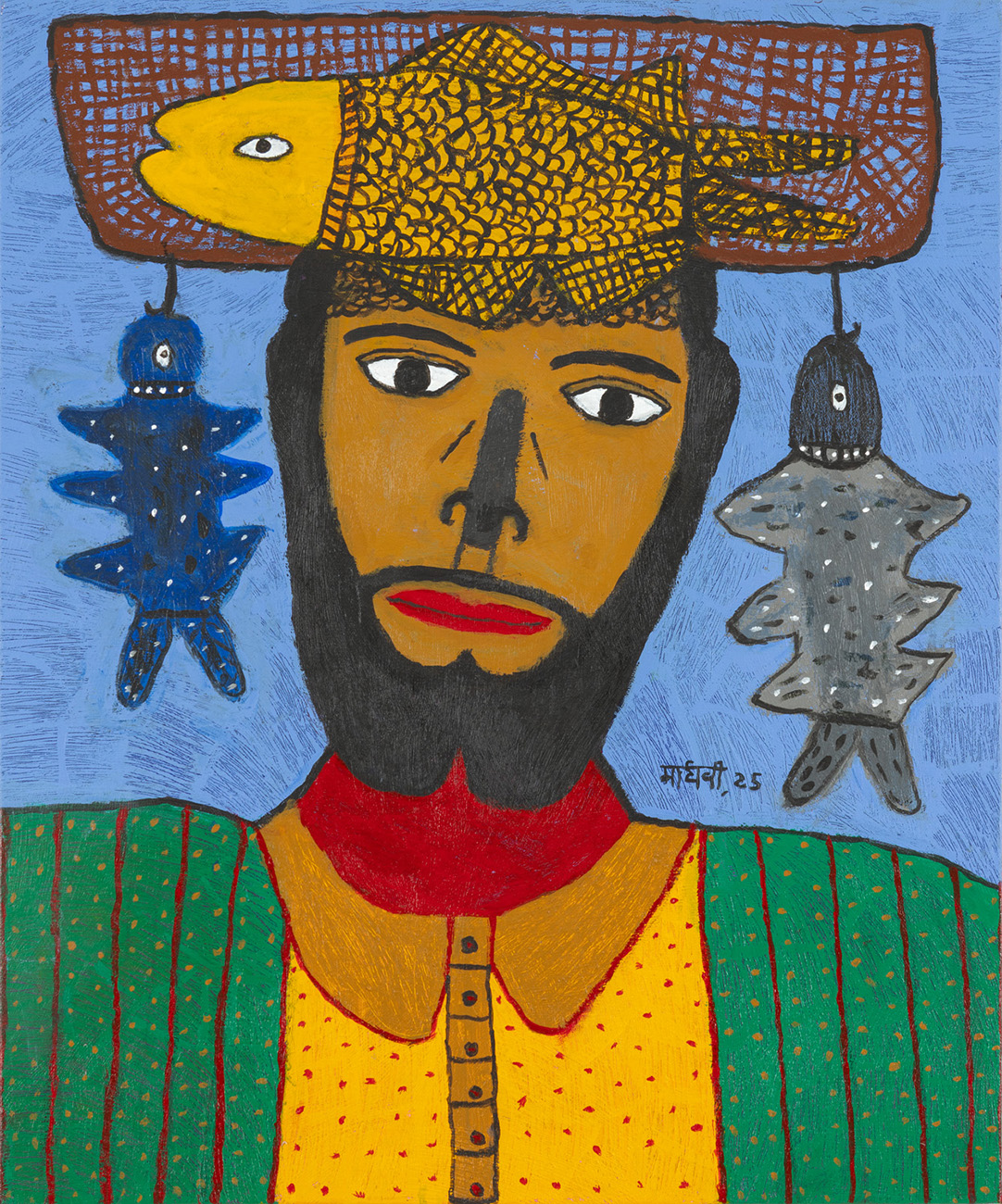

Madhvi Parekh, Fish Seller, 2025, Acrylic on canvas, 30.0 x 24.0 in. Collection: DAG |

Parekh’s oeuvre, spanning more than five decades, reveals an artist engaged not in mere illustration but in philosophical inquiry through form. Her lines, patterns, and repetitions constitute a personal totemism—an inner mythology structured by repetition, intuition, and the instinct to find meaning in the ordinary. Her art unfolds as a meditation on the ordinary made extraordinary through the ritual of personal belief-systems. In her practice, the domestic and the sacred are inseparable: kitchen tables, ladders, and household objects exist in the same symbolic space as goddesses and mythic animals. This layering turns the everyday into a site of cosmology, where routine gestures and forms carry philosophical and emotional weight. As she once observed: ‘Everything I paint comes from memory. Even the dreams.’

|

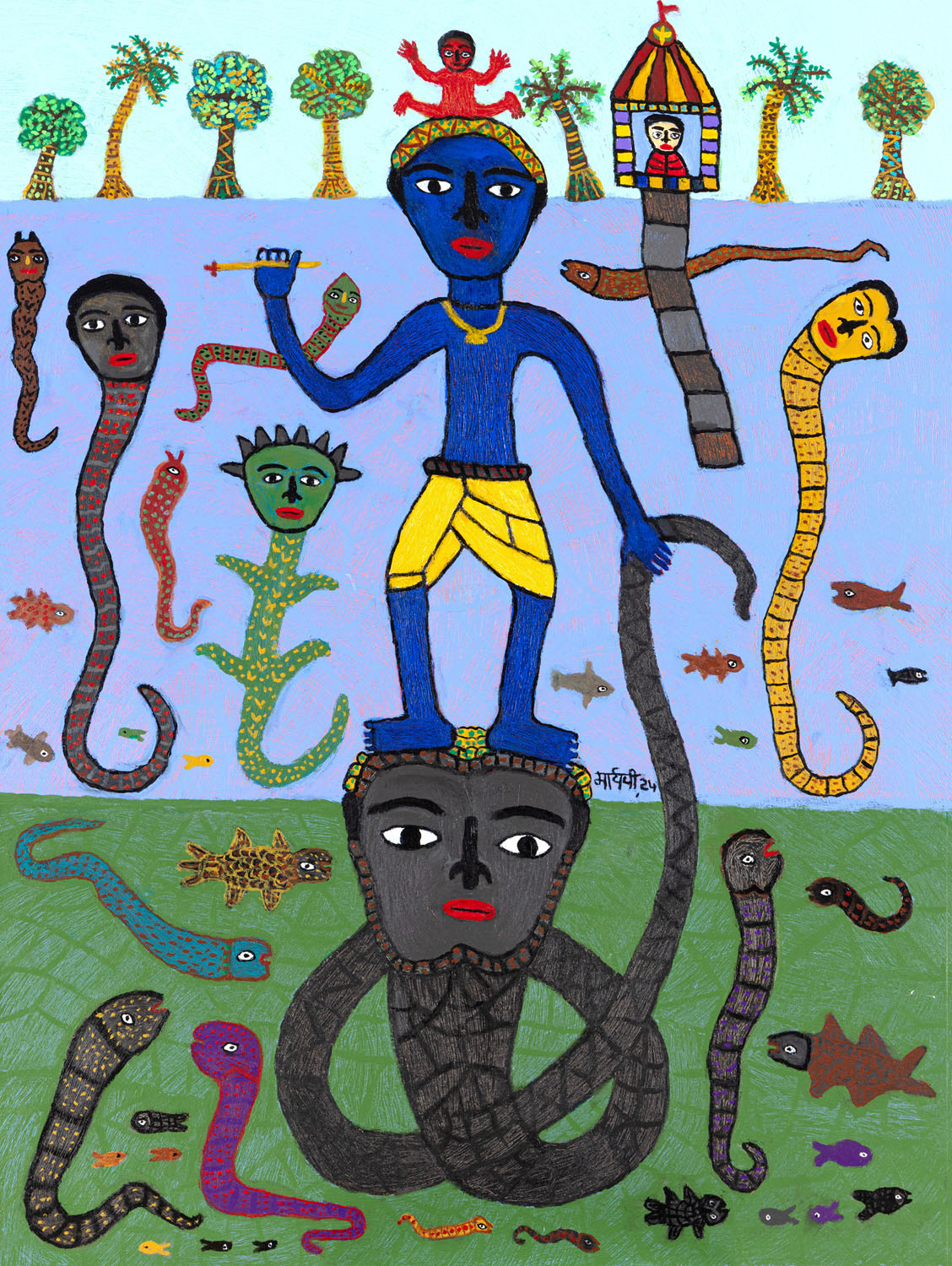

Madhvi Parekh, Kaliyadaman, 2024, Acrylic on canvas, 48.0 x 36.0 in. Collection: DAG |

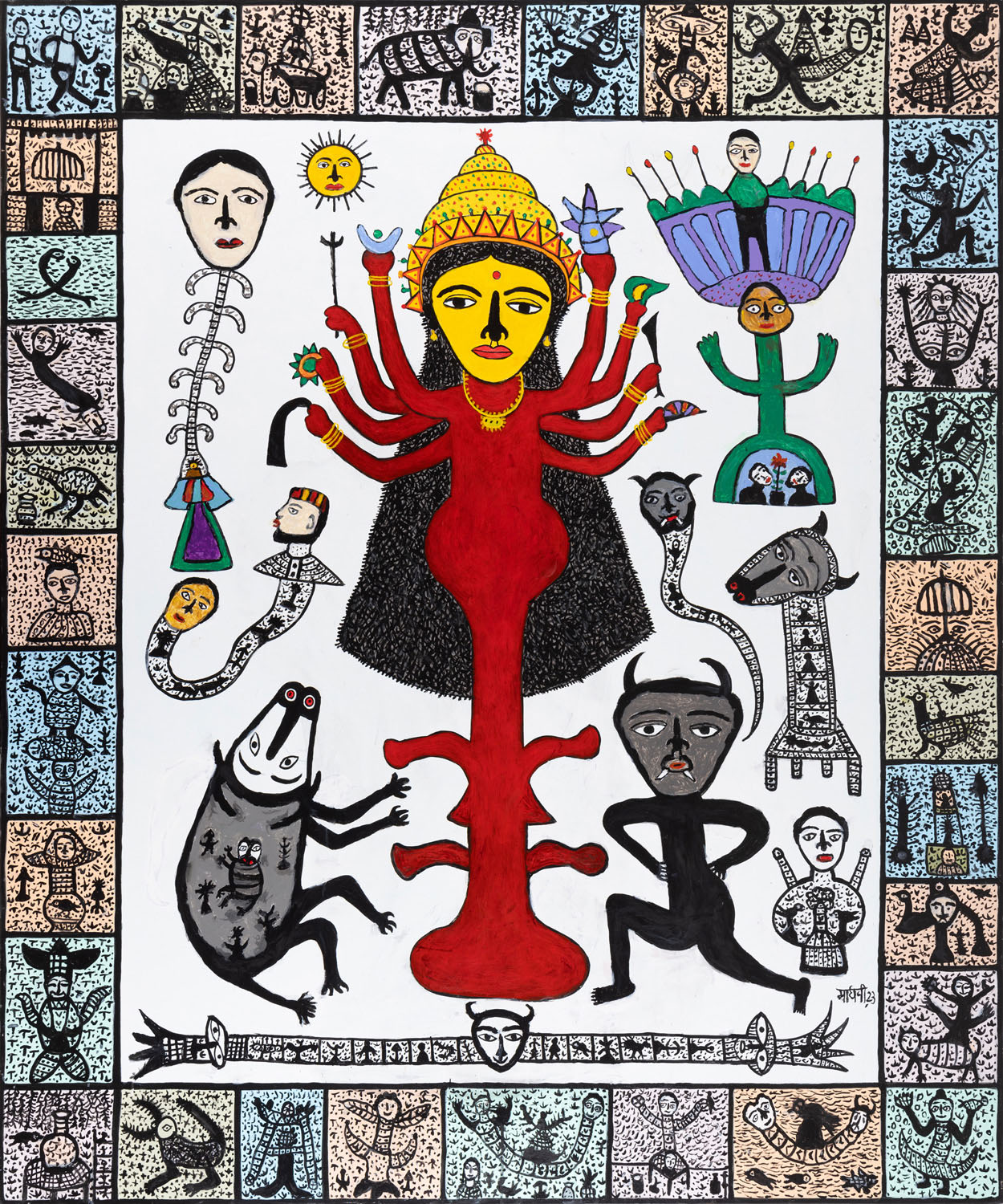

Foregrounding Parekh’s work through a feminine lens allows us to interrogate the patriarchal assumptions embedded in classical anthropology. Traditionally, totems in anthropological discourse, whether in the writings of Emile Durkheim or Lévi-Strauss, were framed as male symbols or vehicles of male lineage, reflecting the male-centric perspective of the observer. Parekh subverts this logic by imbuing her totems—fish, eyes, ladders, and goddesses—with feminine and maternal significance. Her motifs embody care, vigilance, and nurture, transforming objects of symbolic authority into markers of domestic labour and lived experience. In doing so, Parekh not only challenges the gendered hierarchies implicit in anthropological interpretations of totemism but also expands the conceptual field, showing that the sacred, the symbolic, and the cognitive can emerge from female subjectivity and the rhythms of everyday life. This critique is echoed by feminist anthropologist Emily K. Silverman, who in her work Totemism, Society and Embodiment in the Sepik River emphasises that totemic systems are deeply intertwined with gendered understandings of procreation and embodiment.

Madhvi Parekh, Man, Woman and Family, 1996, Oil and charcoal on canvas, 48.0 x 72.0 in. Collection: DAG

Drawing as Bricolage

Parekh’s early sketchbooks provide an intimate cartography of thought. A shopping list, a table, a mother cradling her child—each reappears across pages, gradually stripped of narrative until it becomes emblematic. Her process is one of bricolage—a term Lévi-Strauss used to describe the self-taught maker who constructs new systems of meaning from the materials at hand. Lacking formal training, Parekh turned inward, assembling her visual language through observation and experimentation, even studying figures like Paul Klee to understand how a single line could contain the universe. Her artistic process is less preparatory and more ontological: to draw is to think and to repeat is to remember.

|

Madhvi Parekh, Goddess Durga, 2023, Acrylic on canvas, 72.0 x 60.0 in. Collection: DAG |

Totems of the Everyday

In Parekh’s world, motifs migrate fluidly between the domestic and the divine. In Fish Seller (2025), a bearded man balances a basket of fish on his head; one fish crowns him like a halo. The painting captures the alchemy of transformation: labour becomes ritual, sustenance becomes offering. The fish functions as a totemic device—linking human livelihood to the generative forces of nature. Likewise, in Goddess Durga (2023), Durga and Kali emerge not as distant deities but as presences intimately connected to daily life. Bulls, snakes, birds, and watchful eyes populate the canvas, each symbol oscillating between myth and autobiography. Parekh’s goddesses inhabit the same imaginative space as her kitchen tables and ladders: they are all structures of ascent, mediation, and care.

This entanglement of the sacred and the domestic aligns her with the logic of totemism. In such systems, boundaries between species, worlds, or domains are porous; everything participates in a single symbolic order. Parekh’s art performs precisely this synthesis. Her fish are never only fish, nor her women merely portraits—they are relations. Parekh’s visual vocabulary finds deep resonances with Indigenous and folk visual systems across the world. The parallel is not one of imitation but of shared epistemology: a visual way of knowing that precedes the separation between art, ritual, and life.

Madhvi Parekh, Coming From Heaven, 2000, Mixed media on paper, 22.2 x 30.0 in. Collection: DAG

In the highlands of Papua New Guinea, the late artist Mathias Kauage transformed ancestral myth and daily life into exuberant paintings where men, spirits, and animals cohabit vibrant symbolic space. His figures—rendered in bold outlines and pulsing colour—mediate between the modern and the mythical. Like Parekh, Kauage treated painting as an act of translation, transposing oral cosmology into visual rhythm. Both artists encode transformation as form; Parekh’s Fish Seller mirrors Kauage’s scenes, where work, ritual, and metamorphosis coexist. Their shared chromatic energy and hybrid figuration articulate a belief that the sacred is immanent in the everyday.

In much Indigenous art, the artist serves as a conduit for ancestral voices. Madhvi Parekh reimagines this role through a distinctly feminine lens, turning it into an act of self-creation, so that the goddesses in her work are not external archetypes, but extensions of lived experience: the woman who cooks, dreams, and ascends simultaneously. The domestic space becomes a theatre of cosmology. Through this synthesis, Parekh dismantles the hierarchies between craft and art, folk and modern, feminine labour and artistic authorship.

|

Madhvi Parekh, Goddess of My Village, 2023, Acrylic on canvas, 60.0 x 72.0 in. Collection: DAG |

Born in Sanjaya, a small village in Gujarat, India, in 1942, Parekh’s journey to becoming one of India’s most celebrated contemporary artists was unconventional and deeply personal. In 1964, she married Manu Parekh, a noted artist himself, whose formal training and more traditional approach to art contrasted with Madhvi’s intuitive, self-taught practice. Their shared life has been one of mutual artistic influence, yet it was Madhvi’s decision to step outside the concerns of formal art institutions that made her path particularly subversive.

Unlike many artists who depend on institutional validation, Parekh bypassed formal art education, drawing instead from her own experiences, observations, and daily life. Her tools were her sketchbooks, pens, and watercolours; yet her vision was expansive. By rejecting the conventional structures of the art world, Parekh’s practice became an act of quiet rebellion. Rooted in the domestic and the everyday, her work reflects both personal freedom and artistic autonomy. This refusal to conform transforms her art into more than just creation—it becomes a subtle resistance to established norms, asserting an alternative, deeply individual path within the broader narrative of modern Indian art.

|

Madhvi Parekh, Man with Serpent, 1993, Watercolour on paper laid on mount board, 12.2 x 16.2 in. Collection: DAG |

While Parekh’s art converses with global systems of belief and symbol, it is ultimately an act of modern self-definition. Her totemism is not collective but autobiographical—a language through which a self-taught woman artist negotiates visibility in the modern Indian art world. She reclaims the so-called ‘primitive’ aesthetic as intellectual practice, transforming intuition into method. This places Parekh within a lineage of modernists who transform myth into visual logic, such as Paul Klee, Rufino Tamayo, Frida Kahlo, Mathias Kauage, Heri Dono and John Bevan Ford, among others. What unites them is the conviction that art can think—that images can theorise experience as powerfully as language can.

Lévi-Strauss’s great insight was that symbolic thought is universal; what differs is its idiom. Madhvi Parekh’s idiom is one of tenderness and transformation. Her fish and birds are conceptual tools that help her navigate the intersections of gender, faith, and memory. Through them, she re-enchants the modern world, insisting that myth is not something we outgrow but something we continually remake. To view Parekh’s drawings is to witness anthropology as a self-reflective act. Where Lévi-Strauss sought structures in distant cultures, Parekh finds them in the pulse of her own imagination. Her art suggests that totemism need not belong to the past or to ‘others’; it survives wherever symbols continually mediate between self and world. Parekh simply makes the process visible—her ladders reaching upward, her fish glimmering with remembrance, her eyes wide open to the everyday miracle of form.

Reeti Roy is a writer, cultural commentator, and creative entrepreneur whose work delves into memory, art, identity, and politics. Her writings have been featured in The Wire, The Quint, Scroll, Outlook India, and MargASIA, among others. Bridging journalism, critique, and creative entrepreneurship, she offers nuanced perspectives on contemporary culture. Reeti holds a first degree in English Literature from Jadavpur University and a Master's Degree in Social Anthropology from the London School of Economics and Political Science.