The Year So Far: South Asian Male Physicality at the Art FairsUpasana Das July 01, 2025 The male nude has held a prominent role in Western art since antiquity, gaining particular prominence during the Renaissance, when anatomical studies became central to artistic training. Leonardo da Vinci’s Vitruvian Man exemplifies the era’s pursuit of mathematical precision in depicting the human form. As a prolific anatomist, da Vinci focused largely on the male body—possibly, as Mervyn Levy suggested in The Artist and the Nude, because the male figure more clearly reveals the relationship between muscle, bone, and surface form. According to the art critic Jonathan Jones, Renaissance artists before da Vinci sculpted and painted ‘profoundly characterful’ portraits of men but they did not extend the same treatment to paintings of women. But what can we say about the male nude today? |

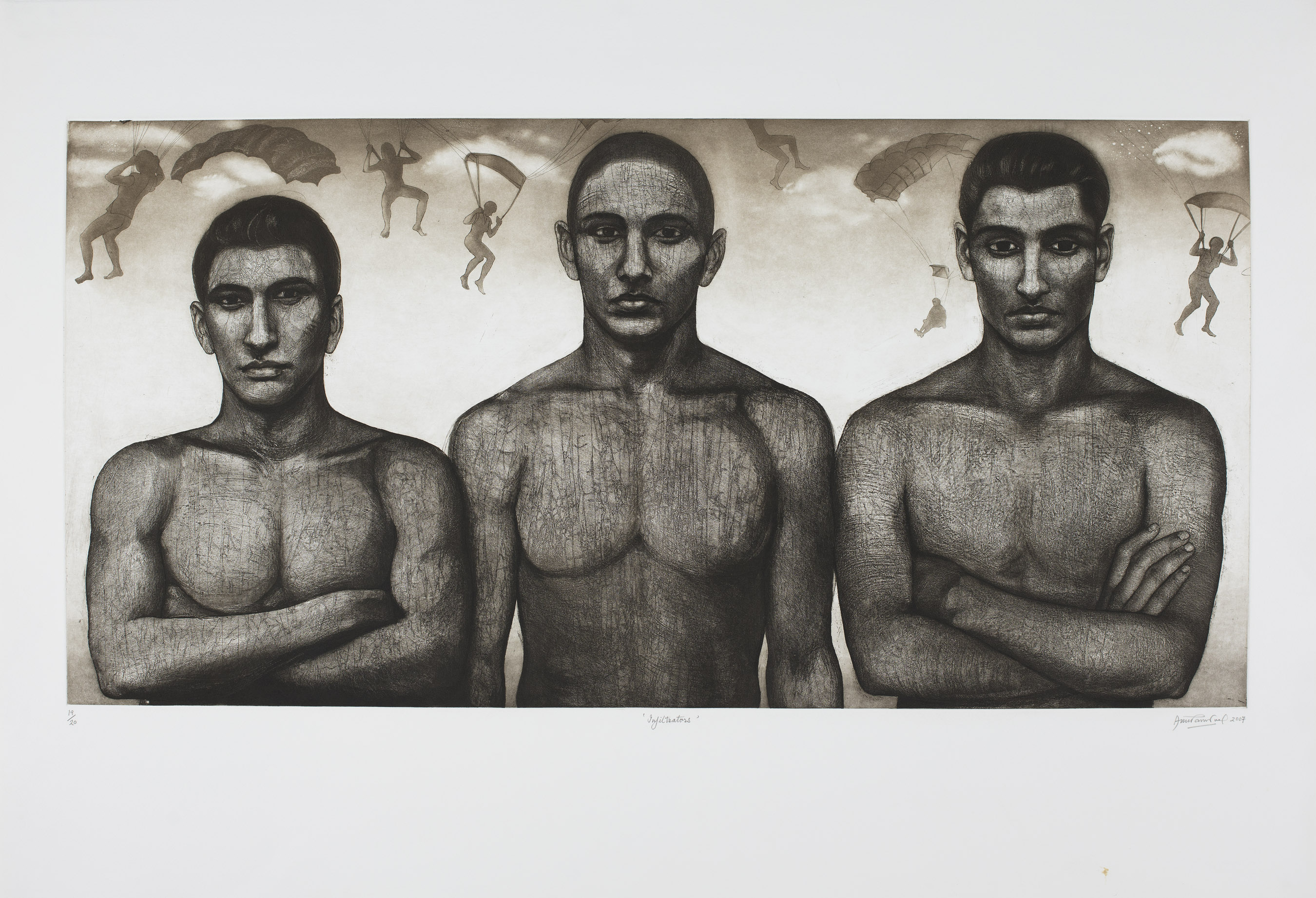

Anupam Sud

Infiltrators

19.2 x 38.7 in. Etching and aquatint on handmade paper, 2007

Collection: DAG

|

Modernism, as art historian Frances Borzello noted, marked the end of the ‘ideal’ nude—but what she really meant was that the nude, reshaped by photography, psychoanalysis, and the trauma of world war, had evolved. In this light, the relative absence of the male nude in Indian art can be traced back to colonial-era training: many modern Indian artists were educated under the British system, which emphasised craftsmanship and studio portraiture. Even artists like Amrita Sher-Gil, for instance, initially followed the salon tradition of posed sitters after returning from Paris. Two years ago, Daniel Larkin asked whether the less-than-idealised body still has commercial appeal in contemporary art (it does, as it turns out). With that in mind, a look at recent art fairs reveals how museums and galleries across India—and more broadly, South Asia—are now engaging with representations of the male body and physicality. |

|

|

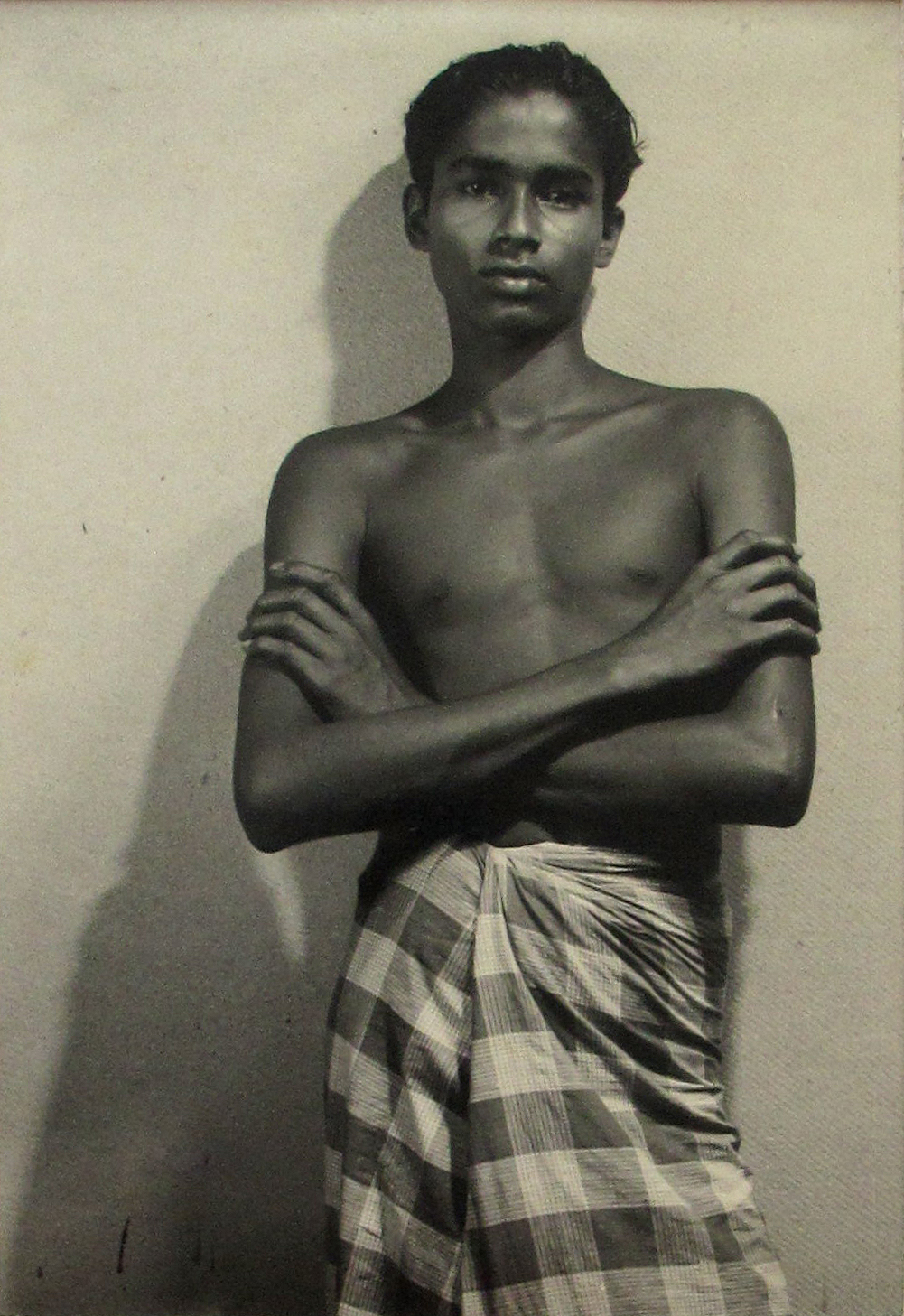

Lionel Wendt

Young man with sarong

c. 1935, Gelatin Silver print, 25 x 17.3 cm.

Courtesy: Jhaveri Contemporary

Lionel Wendt

Portrait of a Young Man

c. 1935, Gelatin Silver Print, 24.8 x 17.5 cm.

Courtesy: Jhaveri Contemporary

Art Basel Hong KongOver half the galleries from amongst the two hundred and forty galleries exhibiting at Art Basel, were from the Asia-Pacific region, including fresh entrants from India. Jhaveri Contemporary highlighted the work of the Sri Lankan photographer, Lionel Wendt. His work has been doing the rounds of the art fair circuit, such as the India Art Fair earlier this year and last year at Art Dubai. Wendt is one of the rare South Asian photographers to work with the non-hypermasculine male body in such a deeply sensual manner amidst strong anti-homosexuality laws in colonial era-Sri Lanka—and perhaps that is what makes the works of this formally trained lawyer and concert pianist, who picked up photography in his 30s, so contemporary. Wendt’s photographs often feature lithe young men with angular limbs, dressed in checkered sarongs or sheer white banyans. One particularly evocative image shows a boy in a translucent sarong, legs splayed to reveal the sculptural qualities of his form. The attention to fabric and pose underscores the sartorial sensitivity of Wendt’s studio practice. His aesthetic sensibility may find echoes in the work of Indian artist Anupam Sud, whose interest in the male form—perhaps influenced by her bodybuilder father—leans more overtly into the muscular and ‘beefcake’ tradition. |

|

‘In college, both male and female models would pose naked, and I always felt that male bodies were more beautiful because they showcased the definition of muscles. Back then—I'm not sure how it is now—unfortunately, many women from very poor backgrounds would come to model. Their bodies were more organic, raw in a way. At home, I would see my mother, who was very fair and delicate, while I was darker in complexion. My teacher would point out the rhythmic lines in the female form, but I found it difficult to grasp. I had never seen women from poor backgrounds standing naked like that before. These are the things I noticed, and they shaped my perspective as a woman.’

|

|

|

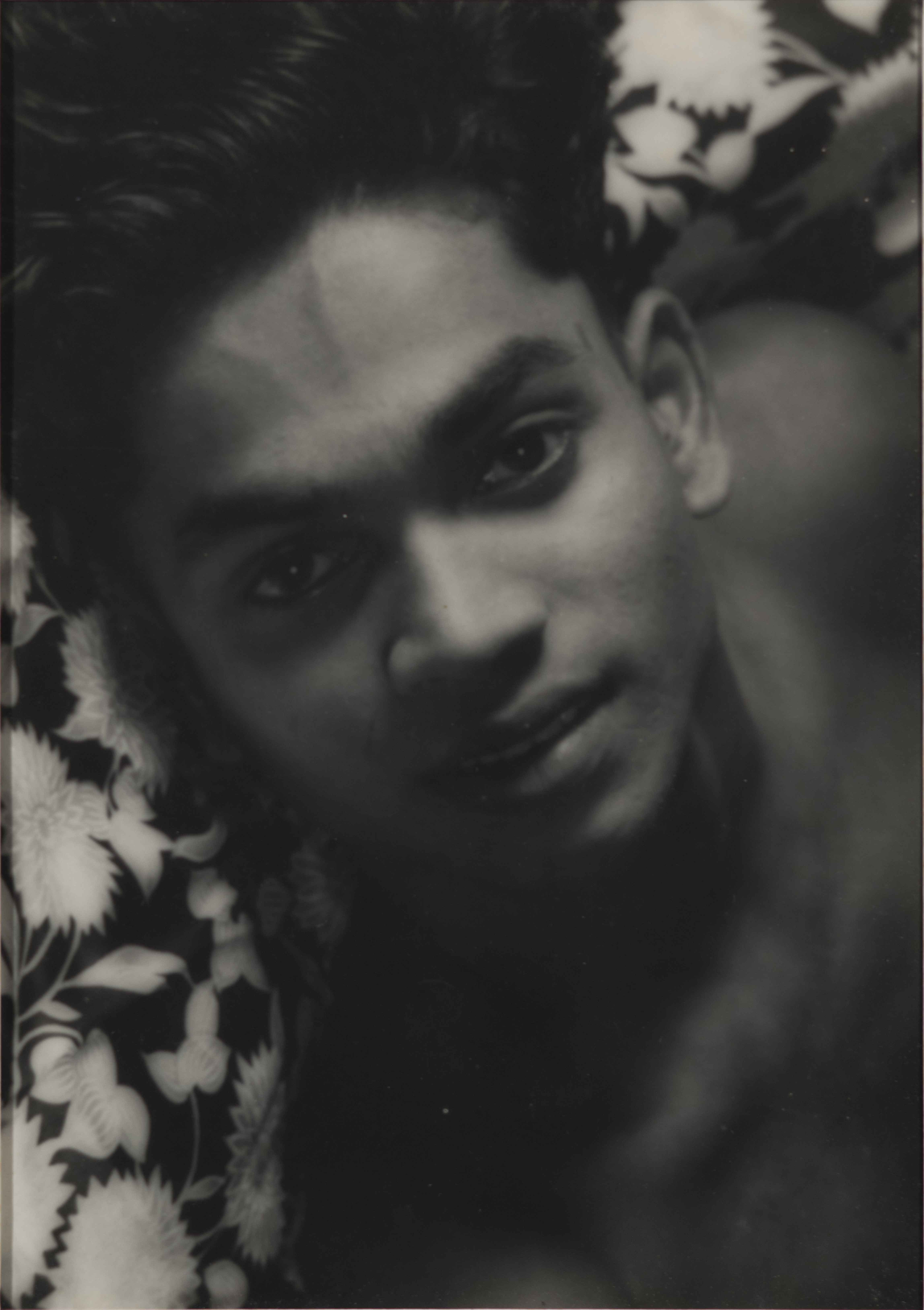

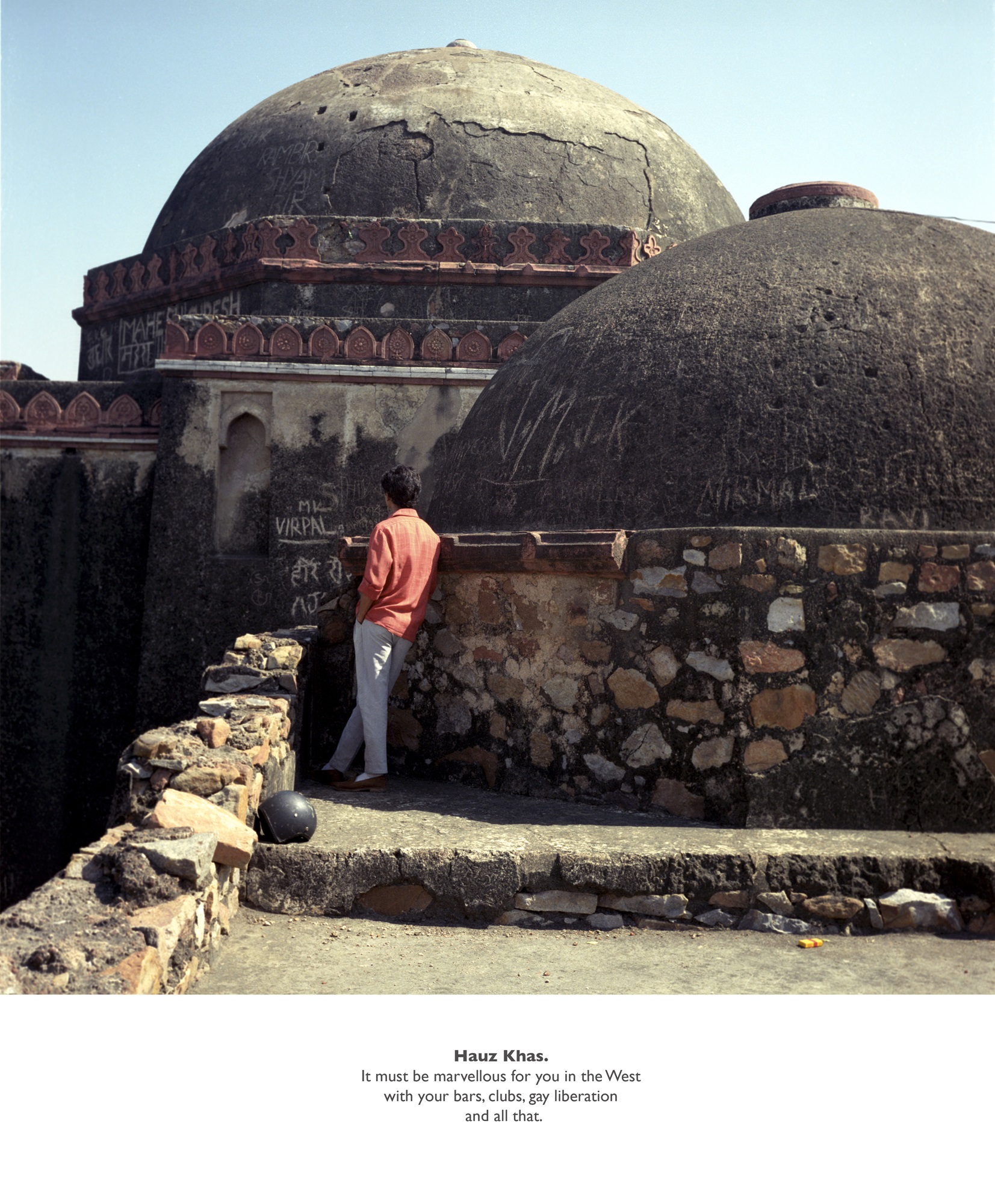

Sunil Gupta

India Gate

1987

Courtesy: Hales Gallery

Sunil Gupta

Hauz Khas

1987

Courtesy: Hales Gallery

Frieze New YorkSunil Gupta’s Exiles remains one of his most resonant and widely recognised bodies of work—marked by the disillusioned wit of a gay man navigating the fragile boundaries of community, identity, and desire within the emerging queer spaces of 1980s urban India. Returning from London during that period, Gupta captured the quiet tensions and longings of a nascent subculture with both intimacy and irony. Last year, a major Indian gallery presented Exiles at Art Basel, where C-type prints sold to private collectors in London. This year, Hales Gallery brought the series to Frieze, reaffirming its enduring relevance in global art discourse. |

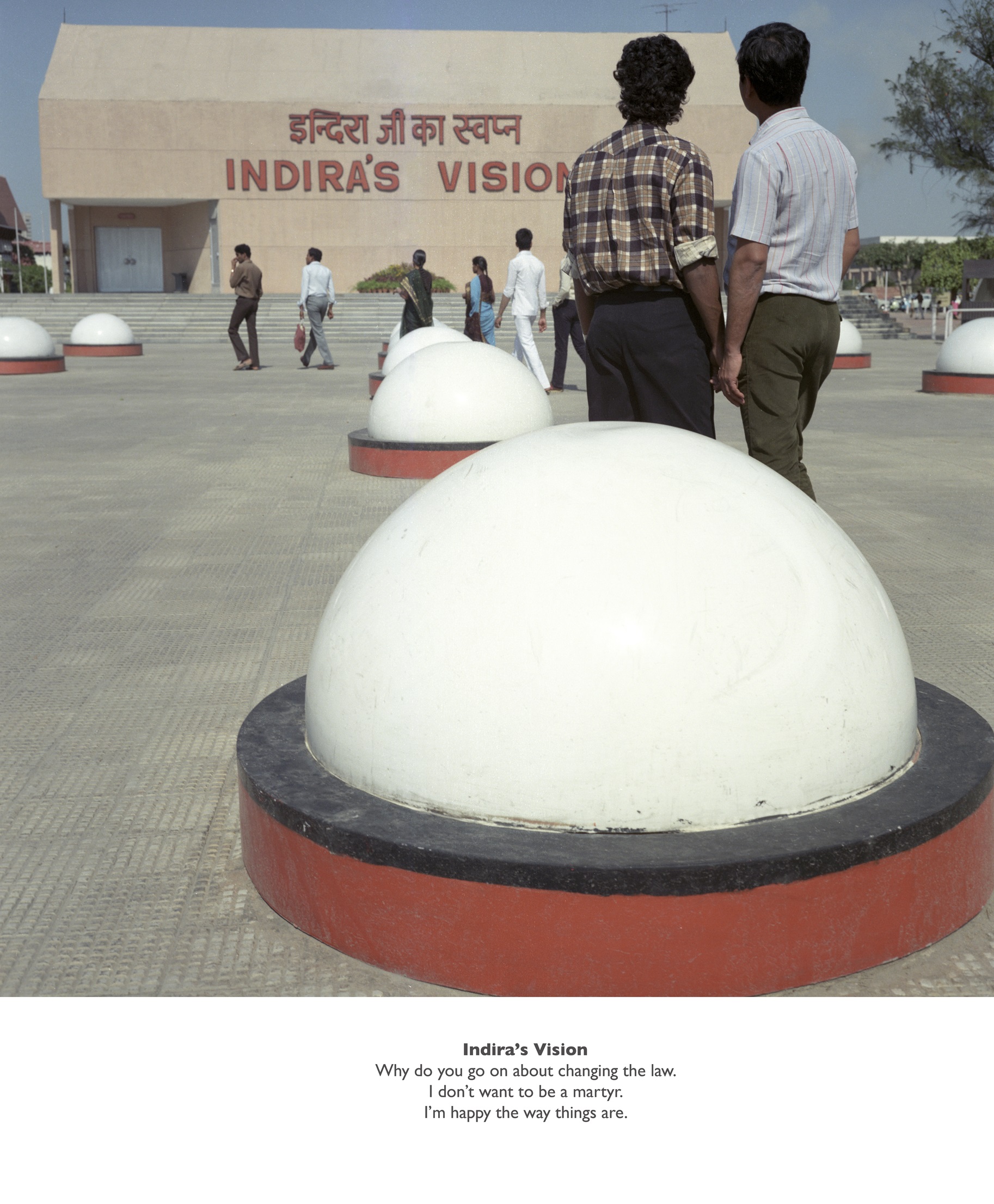

Sunil Gupta

Indira's Vision

1987

Courtesy: Hales Gallery

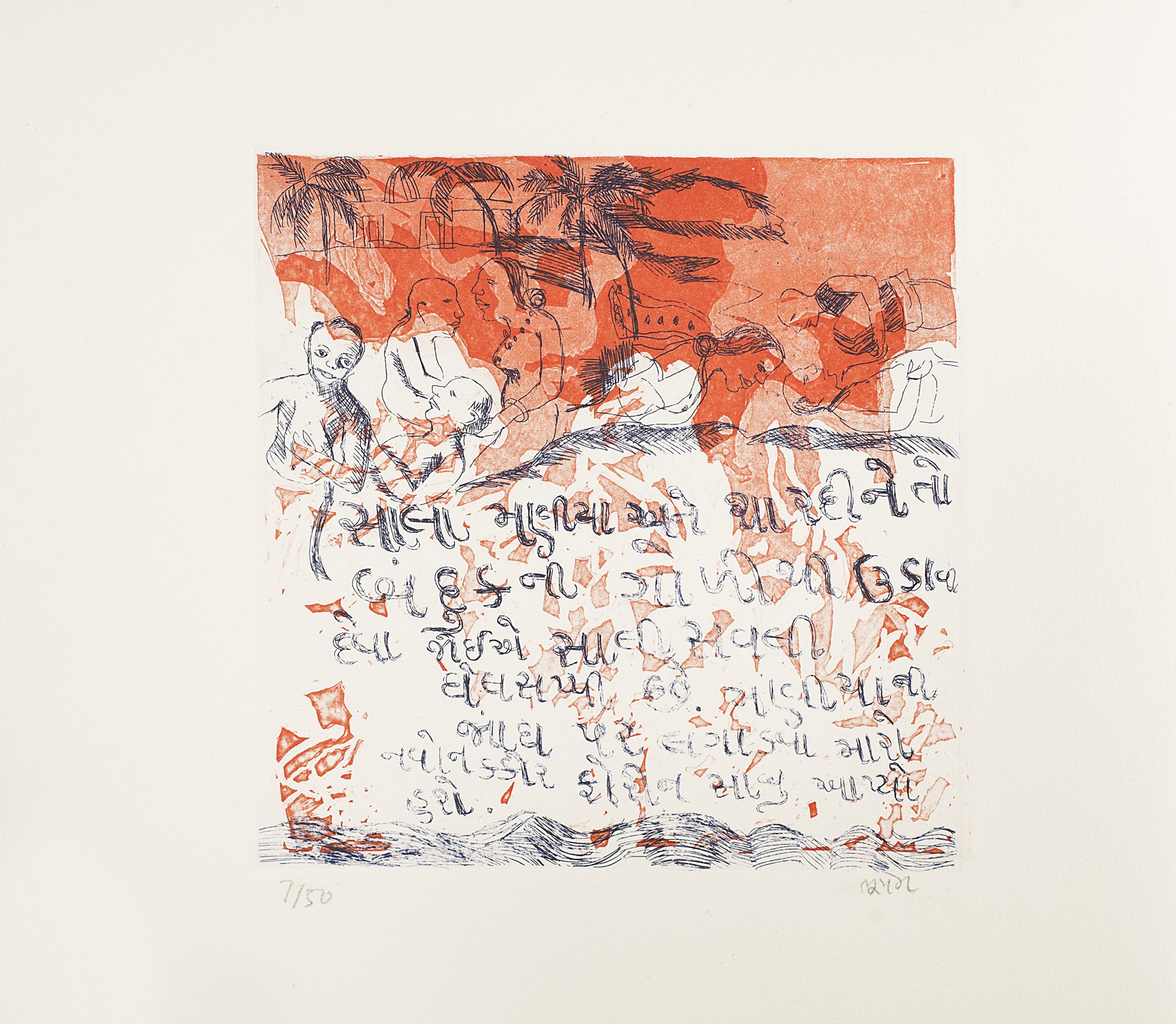

Bhupen Khakhar

Sketchbook (Phoren Soap: An Illustrated Story in Gujarati) (detail)

Etching on paper, 1998, Print size: 6.2 x 6.2 in. Edition 7 of 50

Collection: DAG

A man with smooth, long legs in metallic green shorts, courts another man in Delhi’s Nehru Park; such moments in Sunil Gupta’s Exiles are as performative as they are risky, given that homosexuality remained criminalised in India at the time. Yet Gupta places these bodies unapologetically in public spaces of national and historical significance: an embrace unfolds in front of the Gateway of India; a man in tight jeans gazes up at another in a kurta at Lodhi Gardens; another lounges alone in Hauz Khas. Their quiet sensuality and unmistakable physical presence challenge a society that would have preferred to erase or dismiss homosexuality as either non-existent or a Western imposition. Pushing further, Gupta captures two crossdressing men sharing a moment of joy beneath a portrait of the goddess Lakshmi—a scene that visually echoes Bhupen Khakhar’s Seva (1986), where a man massages another’s leg as temple lights flicker in the background. In both, the sacred and the intimate collide, insisting on queer visibility within the everyday fabric of Indian life. |

|

‘It had always seemed to me that art history seemed to stop at Greece and never properly dealt with gay issues from another place. Therefore, it became imperative to create some images of gay Indian men; they didn't seem to exist.’

|

|

|

M. F. Husain

Arrival

Oil and acrylic on jute

Collection: DAG

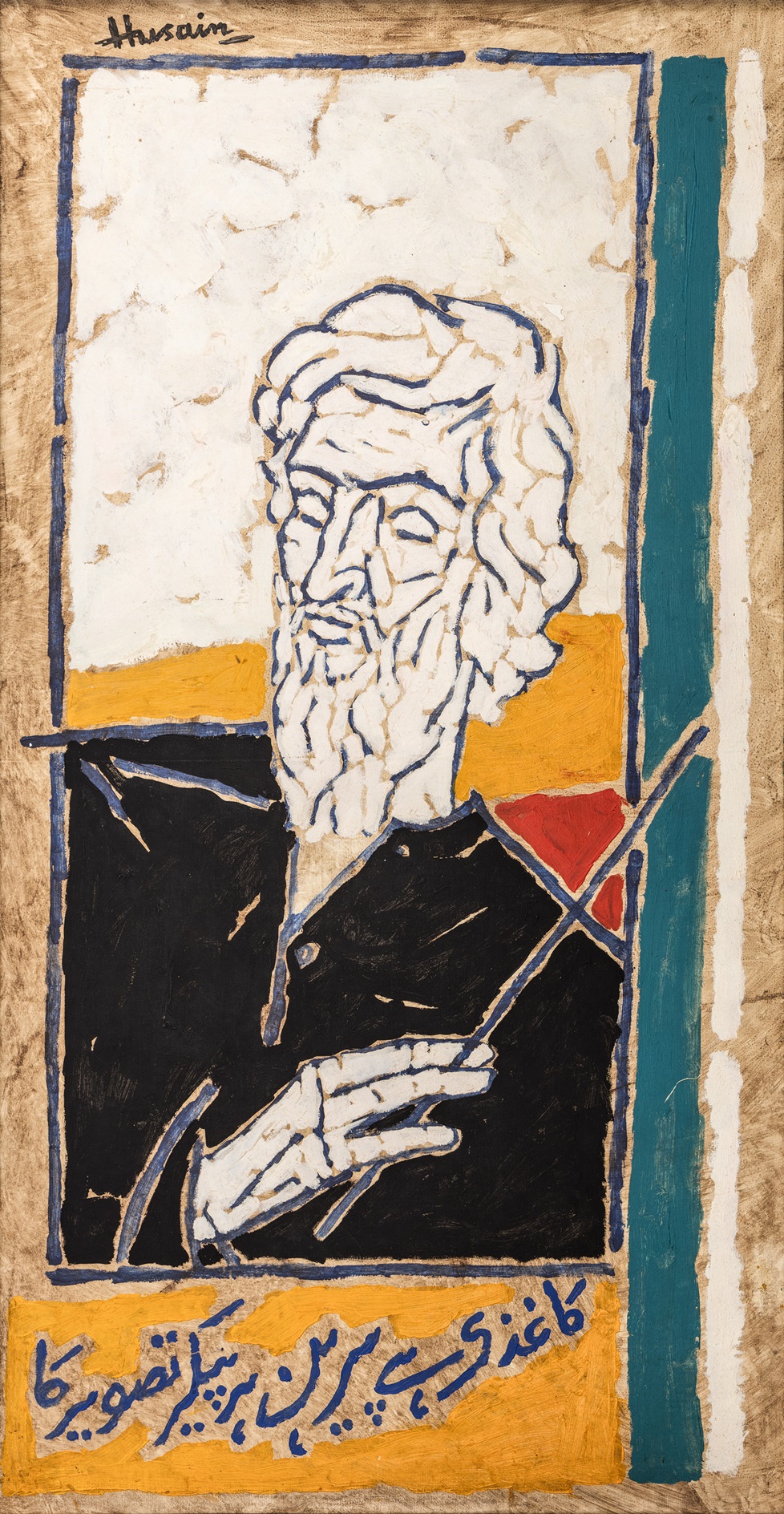

M. F. Husain

Self-portrait

Acrylic on canvas, 50.0 x 26.0 in.

Collection: DAG

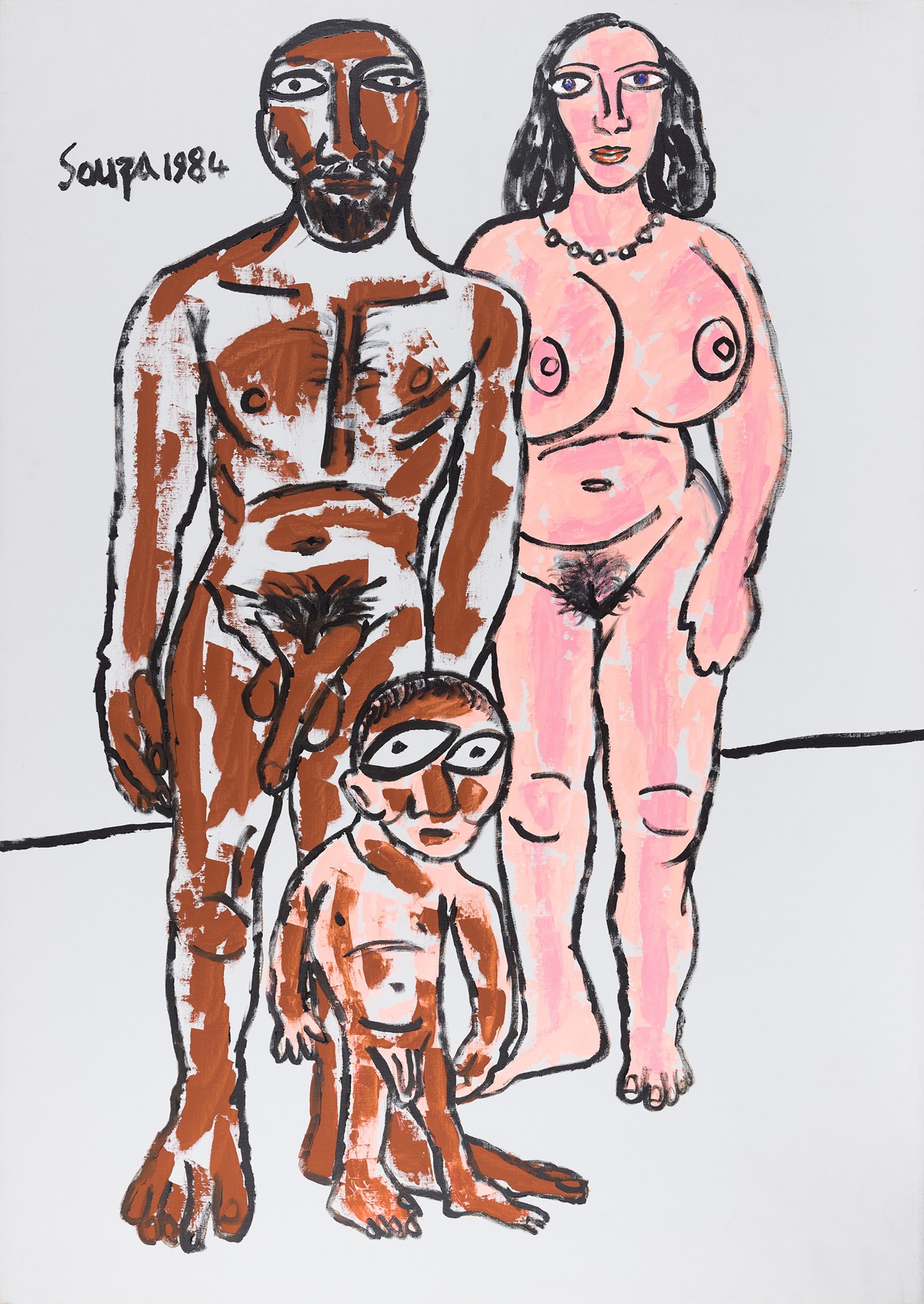

Art DubaiM. F. Husain’s extensive work with the physical form, particularly the female has frequently been tied to his deep yet often uncritical fascination with Hindu mythology, leading him to depict gods in the nude—like Saraswati almost pleasuring herself on the veena or his numerous works around Hanuman, highlighting the monkey god’s physique akin to vintage portraits of broad-chested bodybuilders tapering down to thin waists. The nude man in his work is often sketched in easy cubist lines, their shapes stoic, almost blending into the background, compared to the female who is nearly always in the foreground—a technique also often resorted to by his friend and artist F. N. Souza. M.F. Husain’s Saraswati sparked controversy, and his works continue to provoke strong reactions. One of the most polarizing moments came with his reinterpretation of Bharat Mata, which ultimately led him to self-exile in Qatar. Unlike Abanindranath Tagore’s original, painted during the nationalist movement in a restrained wash that emphasised spiritual serenity and almost transcended the need for physical form, Husain’s version brought the figure firmly into the physical realm. His Bharat Mata was painted in fiery red tones, her contours mapping the borders of the subcontinent—a bold, corporeal reimagining of a symbol long held as sacred. |

M. F. Husain

That Obscure Object of Desire VI

Acrylic on canvas, 50.5 X 104.0 in.

Collection: DAG

F. N. Souza

Untitled (The Family)

1984, Acrylic on canvas, 72.0 X 51.0 in.

Collection: DAG

Perhaps in response to the backlash, Husain later produced a clothed version of the work, which was exhibited at Art Dubai alongside other pieces from his prolific career. Despite the controversies, Husain’s market remains strong: his works brought in ₹119 crore this year, making him one of the most expensive modern Indian artists ever sold at auction. |

|

‘As a child, in Pandharpur, and later, Indore, I was enchanted by the Ram Lila. My friend, Mankeshwar, and I were always acting it out. The Ramayana is such a rich, powerful story, as Dr Rajagopalachari says, its myth has become a reality. But I really began to study spiritual texts when I was 19…When my daughter, Raeesa wanted to get married, she did not want any ceremonies, so I drew a card announcing her marriage and sent it to relatives across the world. On the card, I had painted Parvati sitting on Shiva’s thigh, with his hand on her breast — the first marriage in the cosmos. Nudity, in Hindu culture, is a metaphor for purity.’

|

|

|

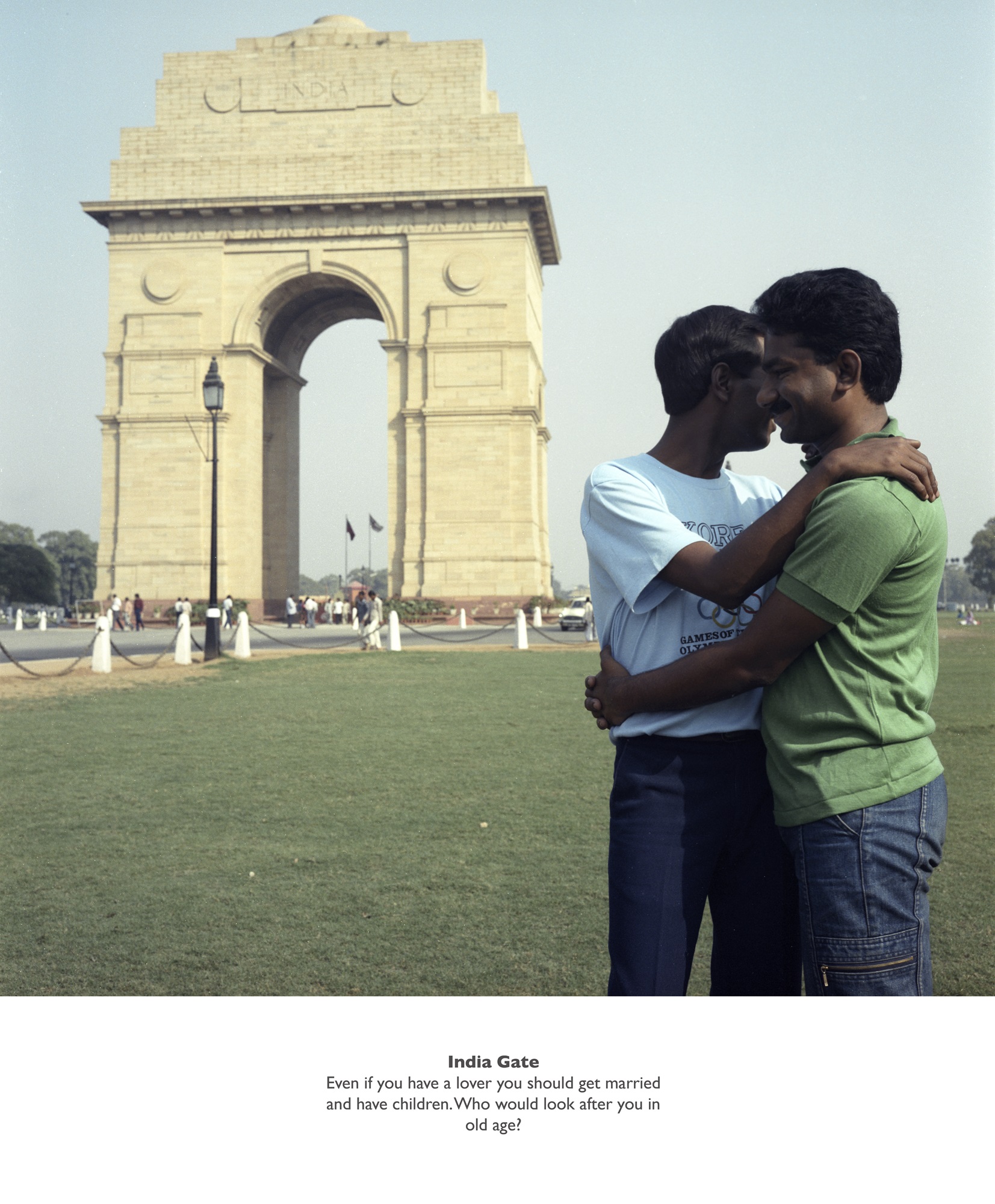

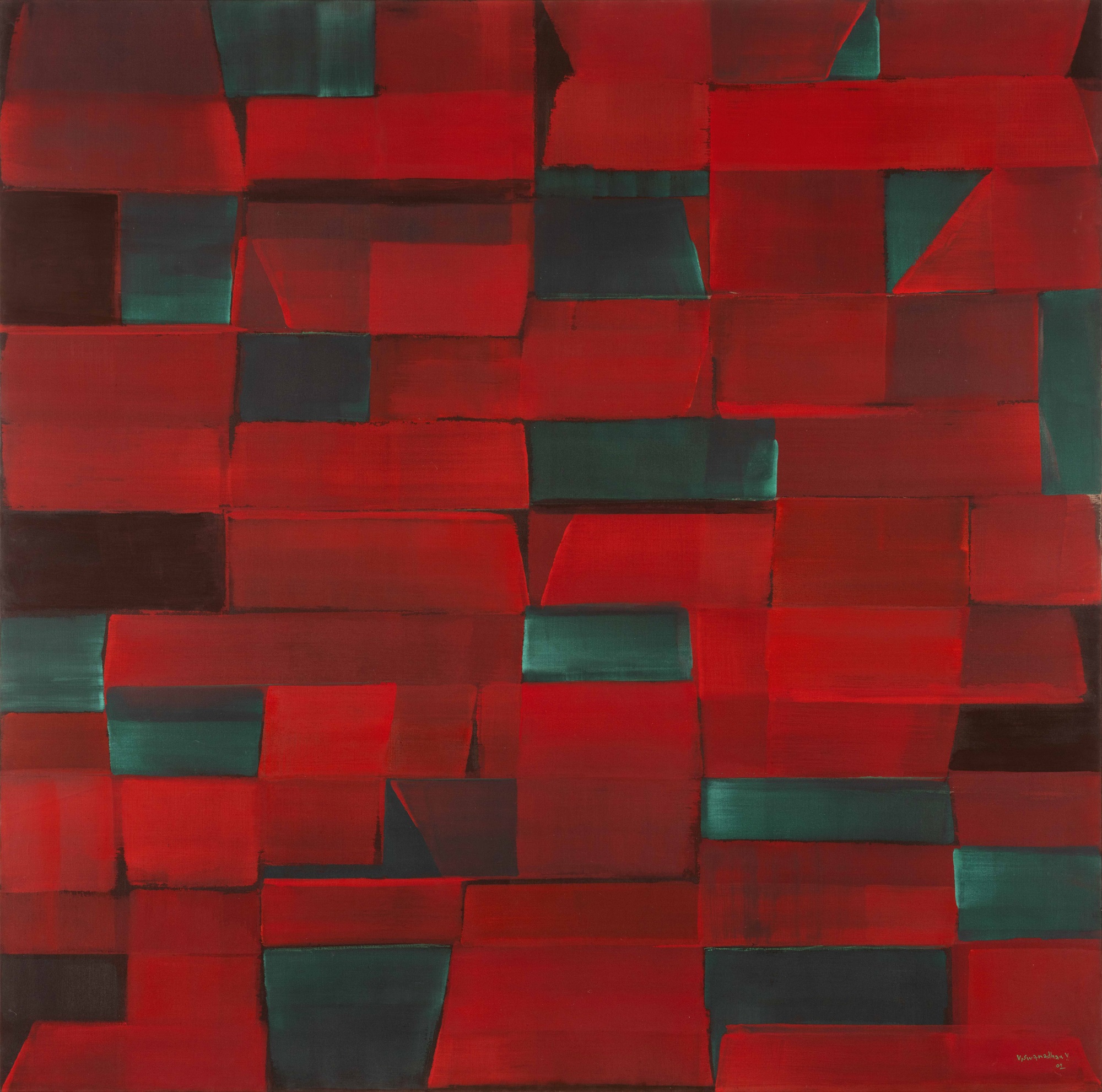

V. Viswanadhan

Sans titre

2002, Casein on canvas, 82 5/8 x 82 5/8 in. / 210 x 210 cm.

Photo credit: Bertrand Huet / tutti image

Courtesy of the artist and Galerie Nathalie Obadia Paris/Brussels

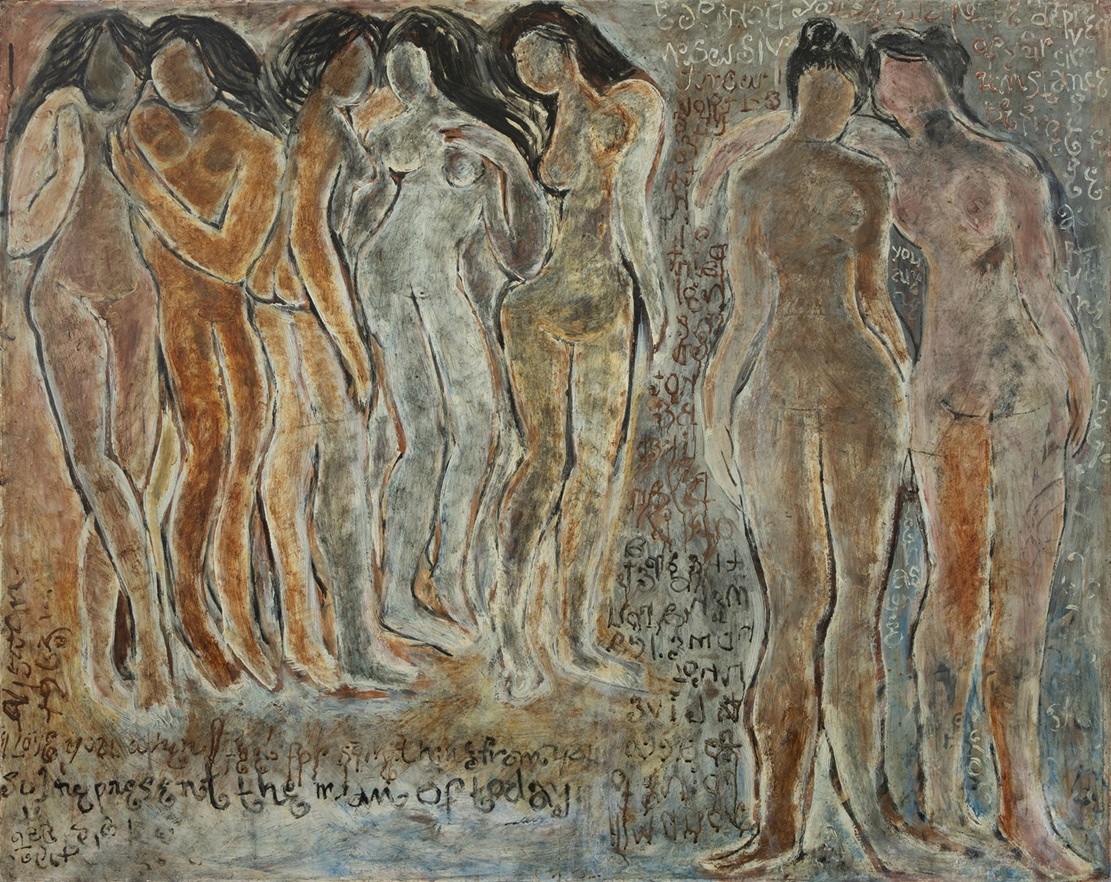

TEFAF (The European Fine Art Fair)It has been a year since Galerie Nathalie Obadia in Paris started representing V. Viswanadhan, who had been living in the city since his arrival in 1968, after establishing the Cholamandal Artists’ Village with K. C. S. Paniker. While the artist is primarily known for his abstractionism—like the work exhibited at TEFAF—he has not always favoured the term being assigned to him. ‘I am not an abstract painter,’ he had claimed, ‘I am not abstracting anything from an image or object. It’s coming from layers of memory, from the imprint of existence. You live it, you feel it, but you don’t paint what you see.’ This is especially true of his works inspired by the architecture of coastal cities. Yet, alongside his foray into geometric abstraction—encouraged early on by K.C.S. Paniker during his time as a student—he also developed an extensive body of work exploring the nude, both male and female, while studying at the Government College of Arts and Crafts in Madras. |

V. Viswanadhan

Standing Nudes

1963, Oil on plywood, 35.5 X 44.7 in.

Collection: DAG

One early work from 1961, depicting the male form, merges bodily structure with spatial architecture in a style strongly reminiscent of Picasso’s Cubism. Drawing inspiration from the modernists of Paris, he reimagined figuration through abstraction—most notably in his interpretations of Kali, where the deity is rendered in fragmented, geometric forms that lend a dynamic sense of movement to her presence. In addition to his swift studies of the female nude on corporate ledger paper, he also collaborated with a French poet on a series of erotic sketches for a limited-edition publication, pushing the boundaries of sensuality within a modernist visual language. |

|

‘How do you place a devi in a mandala and begin to ask questions? First you have to conceive a space where you will install the idol that has to be worshipped. Hence, there is a square opening in all directions, and then the personal deity, which for me is the woman, the female principle. I was looking at this even in my nude studies in Madras. When you look at Munch’s Scream, the central theme is woman. Then I came to the triangle, which is the woman. Whether it is figurative or abstract, it is about the woman. What else is life, but woman?’

|

|

|

Viswanadhan

Various works,1968 - 2011.Installation view: Sharjah Biennial 16, Gallery 4, Al Mureijah Square, Sharjah, 2025

Photo: Ivan Erofeev

Viswanadhan

Various works,1968 - 2011.Installation view: Sharjah Biennial 16, Gallery 4, Al Mureijah Square, Sharjah, 2025

Photo: Ivan Erofeev

Sharjah BiennaleThis year, Sharjah dedicated an entire pavilion to Viswanadhan, showcasing not only his abstract works but also his collaborations with filmmaker Adoor Gopalakrishnan. Among these was Sable/Sand, a film capturing Viswanadhan’s process of collecting sand from the coast for his artwork. Accompanying the films was a series of photographs taken by Viswanadhan and Gopalakrishnan. ‘The photographs are really vignettes of studying the labour that is carried along the coastline, rituals, and the kinds of species that inhabit the areas around beaches — but also a way of thinking about imperial histories and voyagers who came,’ said Natasha Ginwala, one of the curators of this edition of the Biennale. With maritime commerce, Viswanadhan and Gopalakrishnan also highlights masculine bodies of labour on the sea, their movements silhouetted against the sharp sunlight as they rowed their boats or collectively pulled them back to the shore—or sometimes simply boys playing on the shore. Galerie Nathalie Obadia will also be taking Viswanadhan works to the upcoming Art Basel. |

|

‘The boys, shy, would sit in the corners. I used to place the models in a certain way. I was a daredevil of sorts. We did big drawings of nudes. In the early images, we were researching the form. I had seen Munch’s Scream. Hence, the series called Agony with female figures. It was a question of finding the form, of forming your vision.’

|

|

|