The White 'Other': Marginal Europeans in Colonial India

The White 'Other': Marginal Europeans in Colonial India

The White 'Other': Marginal Europeans in Colonial India

collection stories

The White 'Other': Marginal Europeans in Colonial IndiaVinayak Bose The Calcutta Gazette, in March 1791, advertised the impending arrival of The Etrusco, a cargo ship from Ostend, upon which 'the public will have an opportunity of being supplied with a great variety of articles, all of the best kind.' This ship, along with its advertised goods, also brought a Flemish artist in his 30s who, like many others, hoped to make his fortune in the Colony. However, during this time, one required permission from the East India Company's (E. I. C) Board of Directors to live and trade in Calcutta, and this young artist, Francois Baltazard Solvyns, did not have one. |

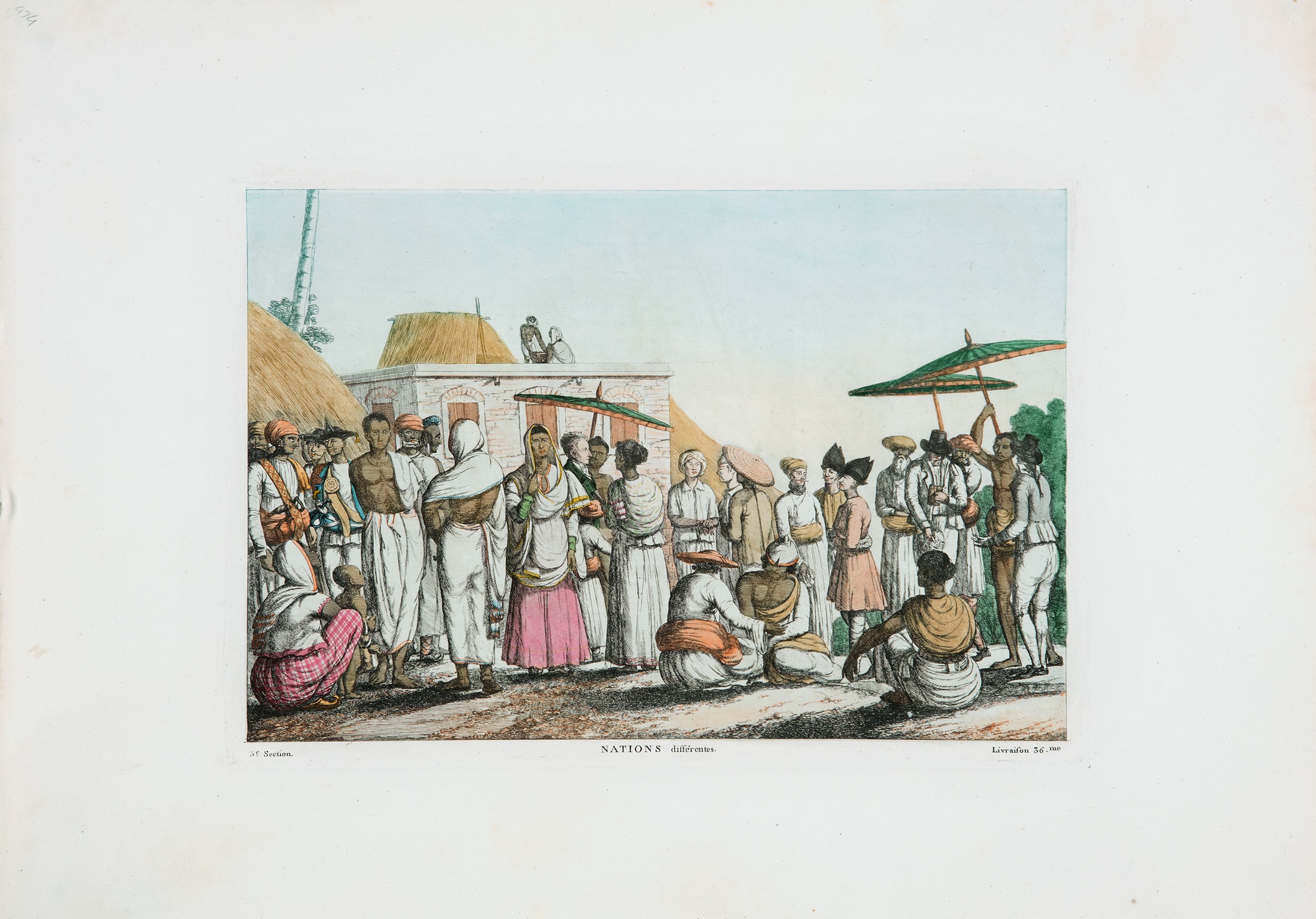

F. B. Solvyns

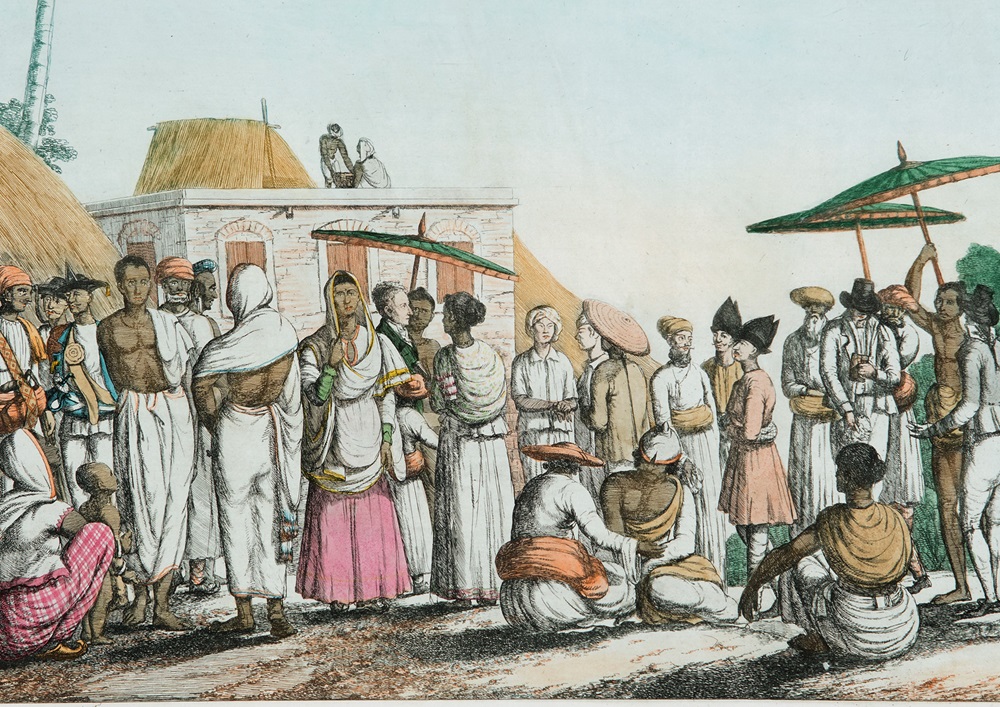

Nations differentes (different nations) (detail)

Vol. III, number 12, plate 5, 1811, 25 x 36 cm.

Collection: DAG

|

The White 'Other’ is the story of those living outside the remit of the society of Company-sanctioned Europeans enjoying the opportunities and treasures of Empire. |

|

|

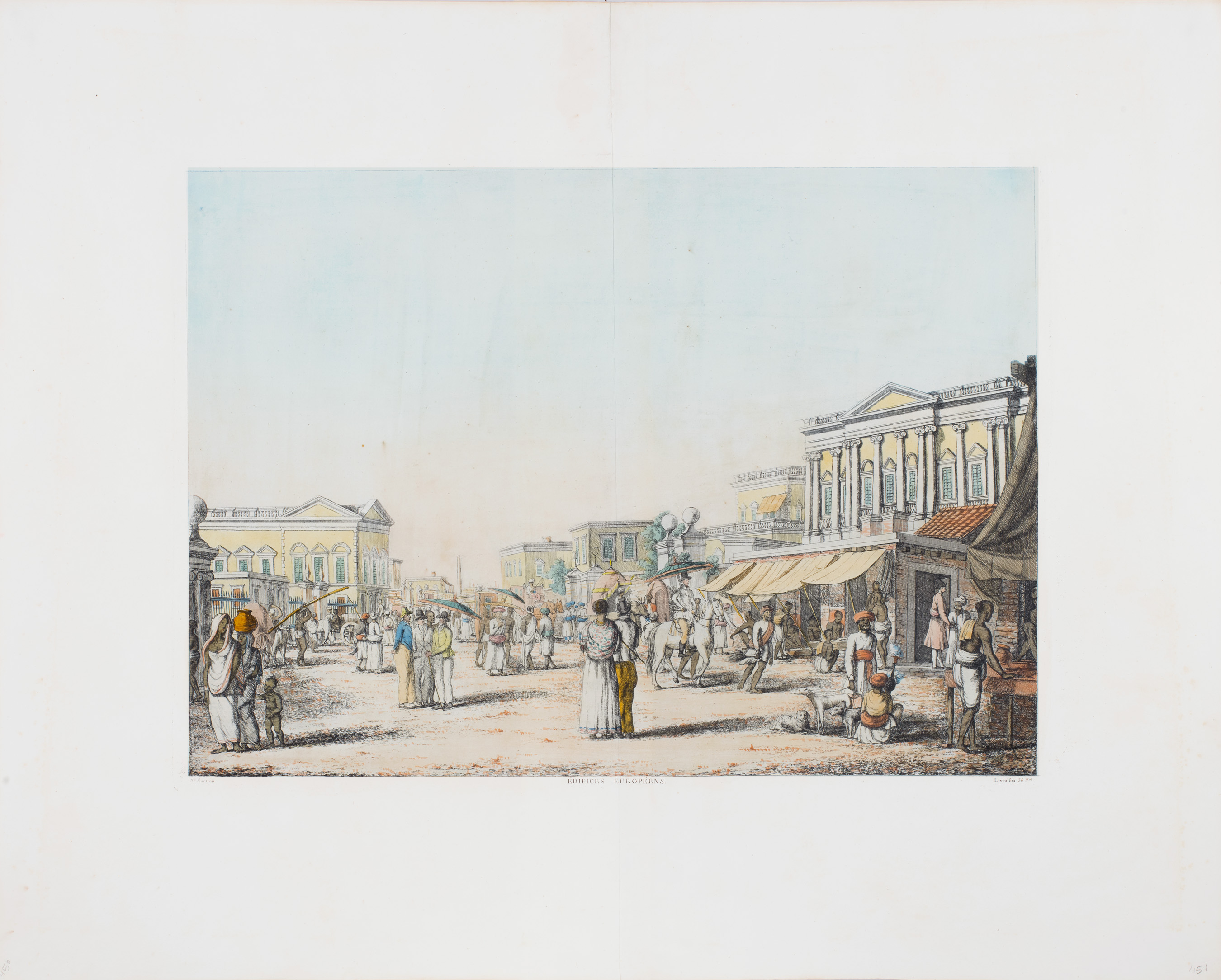

Thomas Daniell

View taken on the Esplanade, Calcutta

1797, Hand-tinted engraving on paper, 17.7 x 23.5 in.

Collection: DAG

Unidentified Painter

Sir Home Riggs Popham

c. 1783, Oil on canvas

Image courtesy: Wikimedia Commons

A ship treading the grayThe Etrusco was not the most law-abiding vessel. Its captain, Home Popham, had taken a leave of absence from the Royal Navy in 1787 and for the next six years engaged in unsanctioned mercantile enterprises.

Popham found confidence in his felonious ventures because of his friends in the Bengal government, and the endemic corruption in Calcutta. |

|

Importance of the Permit By 1791, when Solvyns arrived, artists such as Tilly Kettle, John Zoffany, William Hodges, and the Daniells, had already established themselves in India. However, they had official sanction to live in India in the form of a Company permit —which Solvyns did not have. |

|

|

William Hodges

A View of Chinsura, the Dutch settlement of Bengal

Hand-tinted engraving on paper

Collection: DAG

A feature of the East India Company's monopoly was its policy of forbidding Europeans other than Crown or Company servants to reside in India without a license from the Court of Directors. Their aversion to the settlement of non-official Europeans in the 1790s was strict. Licenses were granted with great caution; the immigrant was required to state directly the occupation they intended to follow, and the local authorities were instructed to send him back if he was found to have deviated to another vocation. The permits typically also included a 'bond of good conduct'. For an artist like William Hodges, the first official landscape artist for the E. I. C. in India, the process was smoothened by his fame in London, which led to Warren Hastings inviting him to the new colonies. This invitation helped him secure a permit easily. |

Thomas Daniell

View on the Chitpore Road

Tilly Kettle

Shuja-ud-Daula, Nawab of Oudh

Johann Zoffany

Colonel Mordaunt’s Cock Match

|

F. B. Solvyns: A 'marginal' artist? |

|

|

Arthur William Devis

A Gentleman, possibly William Hickey, and an Indian Servant

c. 1785, Oil on canvas

Yale Center for British Art. Image courtesy: Wikimedia Commons

Despite his education and the respected position of his family in Antwerp, Solvyns remained something of an outsider to European society in Calcutta. His lack of a formal introduction in Calcutta closed off the niche coteries to him; the most vexing being his inability to gain membership to the Asiatic Society of Bengal. Established in 1784, the Asiatic Society had given memberships to artists like Johann Zoffany, Thomas Daniell and Arthur Devis. His exclusion from the Society suggests an isolation from the company of those who most closely shared his interests, and a lack of networking in a difficult market. |

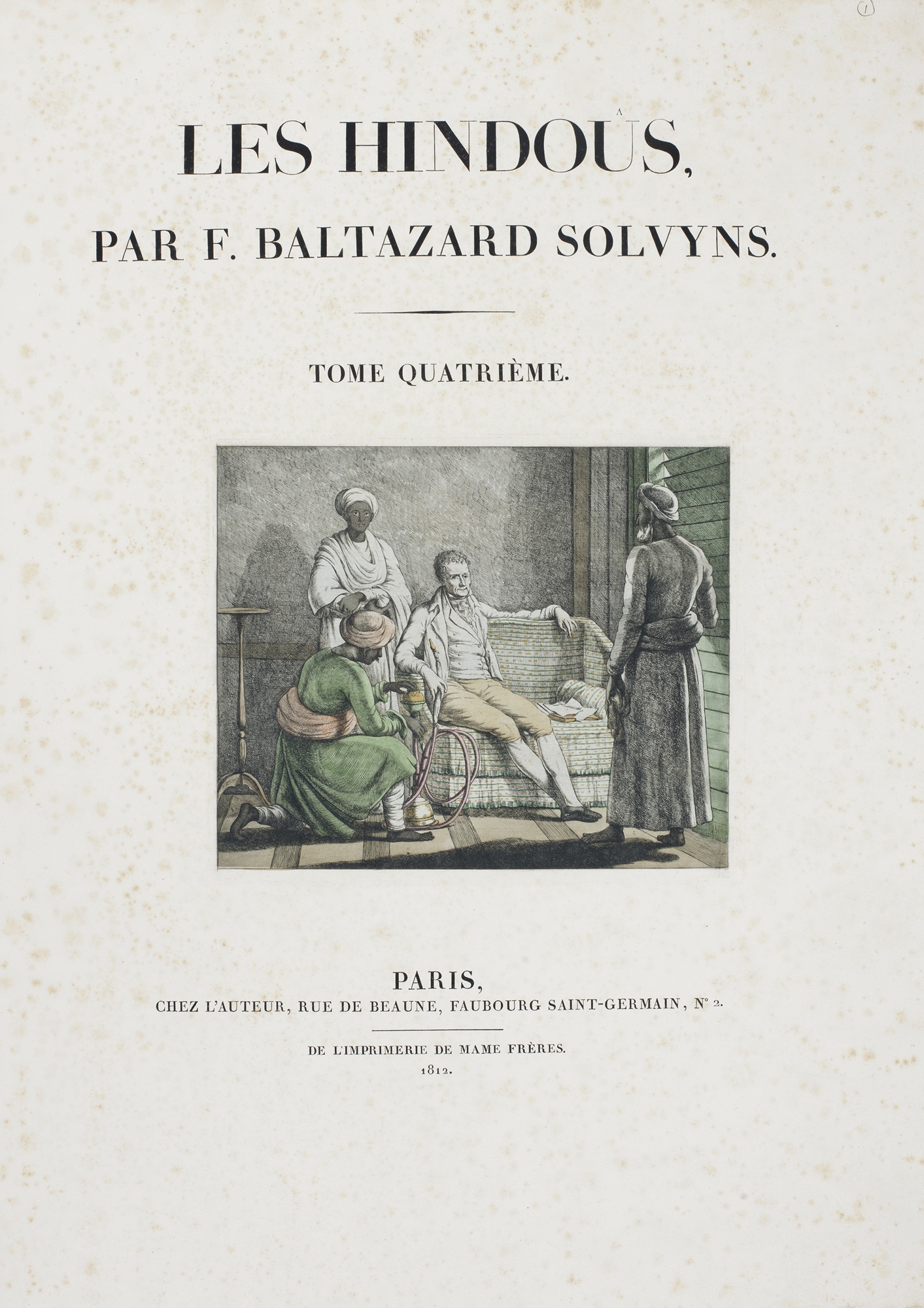

F. B. Solvyns

Cover: Les Hindous Volume IV Paris Edition

1810, Colour etching

Collection: DAG

It was perhaps because of his arguably 'marginal' status in Calcutta's European society that contemporary discourse finds distinction in his works when compared to his contemporaries who had lived and worked in Calcutta. Solvyns' lack of wealthy patronage and his limited residential access to 'White Town' gave him leave to access parts of the city unfrequented by Europeans. He created a visual record of all the various ethnic groups he came across in Calcutta and their way of life through a series of etchings. This endeavour is valued as one of the first visual ethnographic records of the people of Calcutta by a European. |

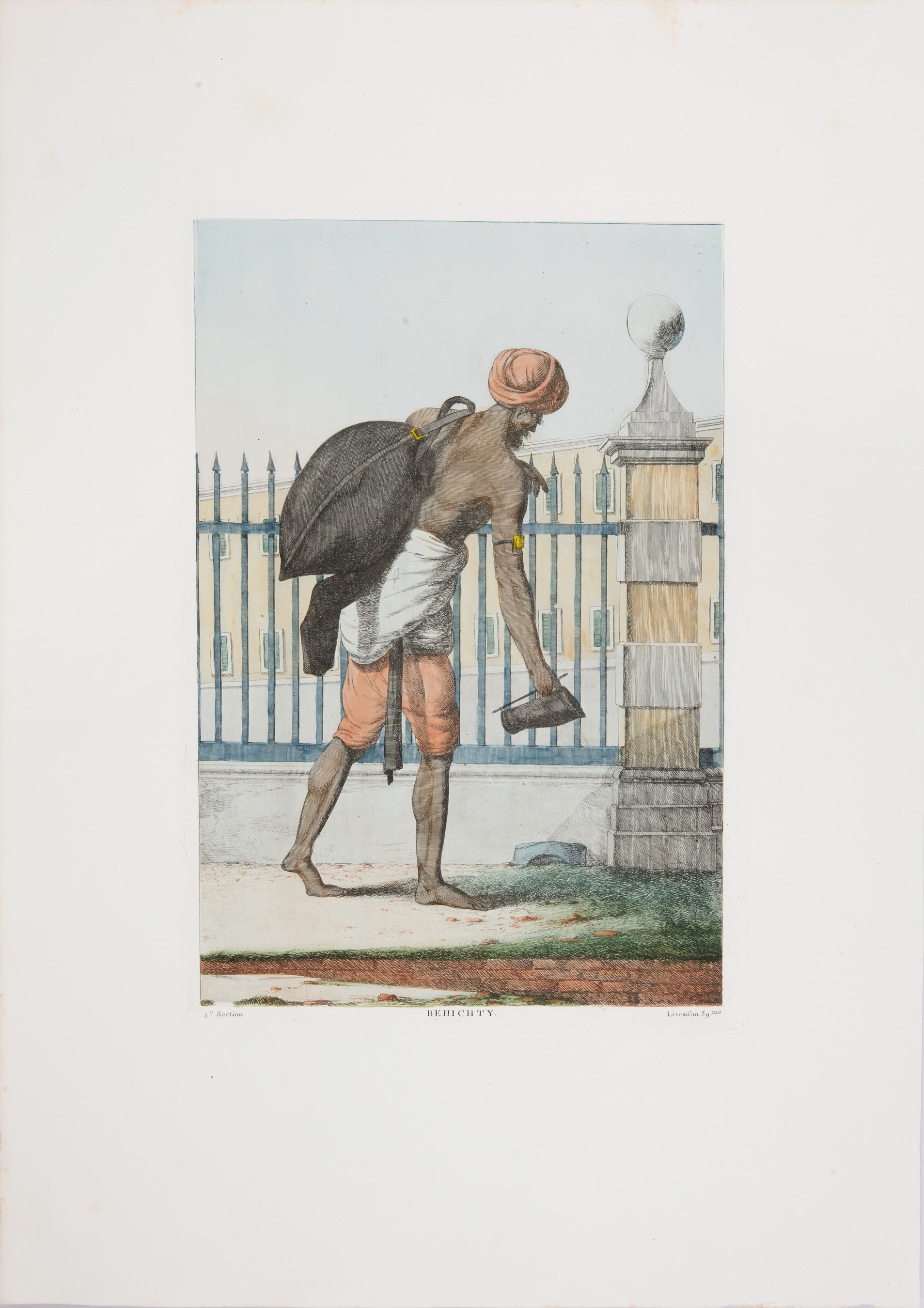

F. B. Solvyns

Day (dai, wet-nurse)

F. B. Solvyns

Behichty (bhisti)

F. B. Solvyns

Edifices Européens (European Buildings)

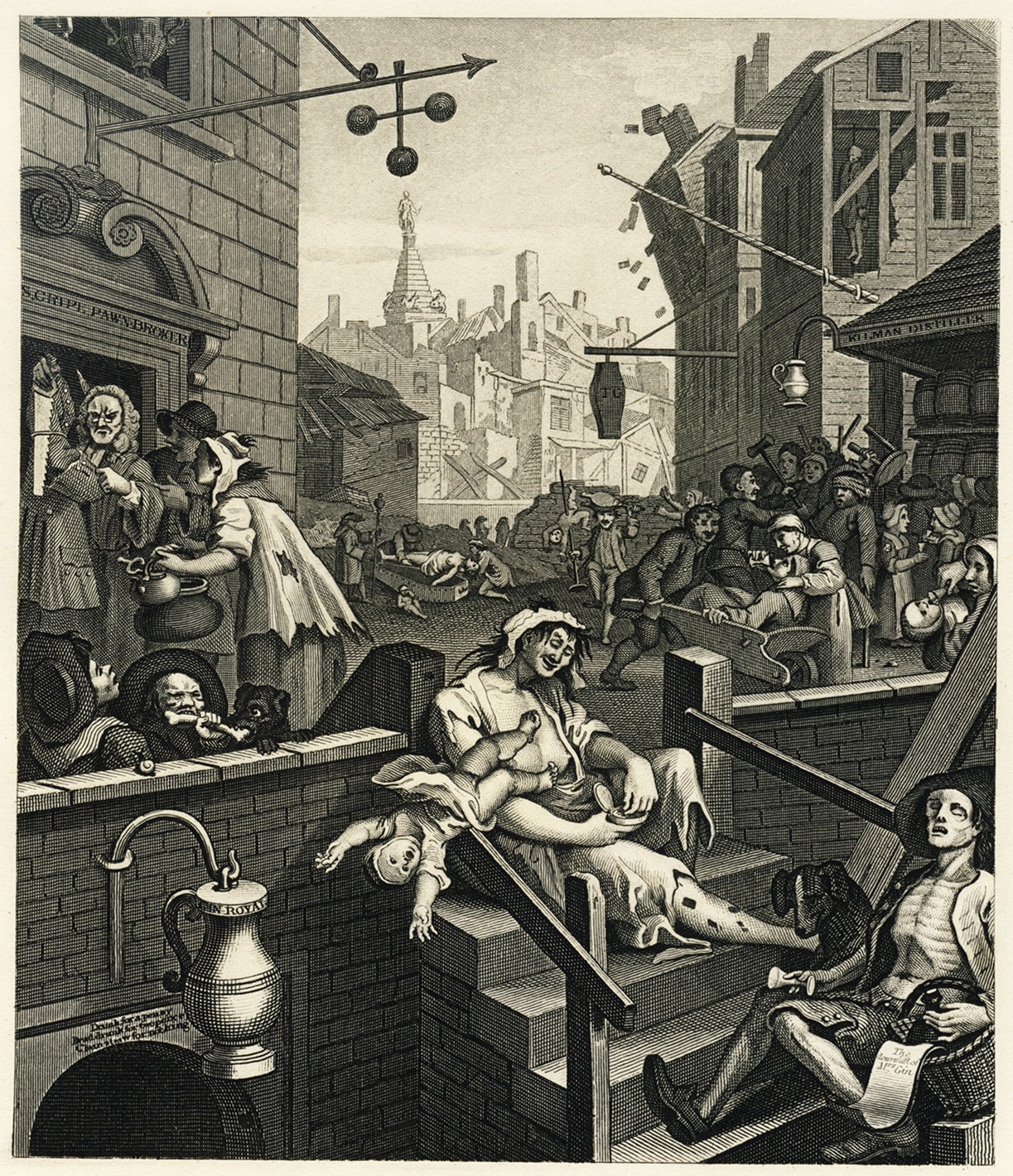

William Hogarth

Gin Lane

F. B. Solvyns

Nations differentes (different nations)

F. B. Solvyns

Chaise Palanquin

1810, Colour etching

Collection: DAG

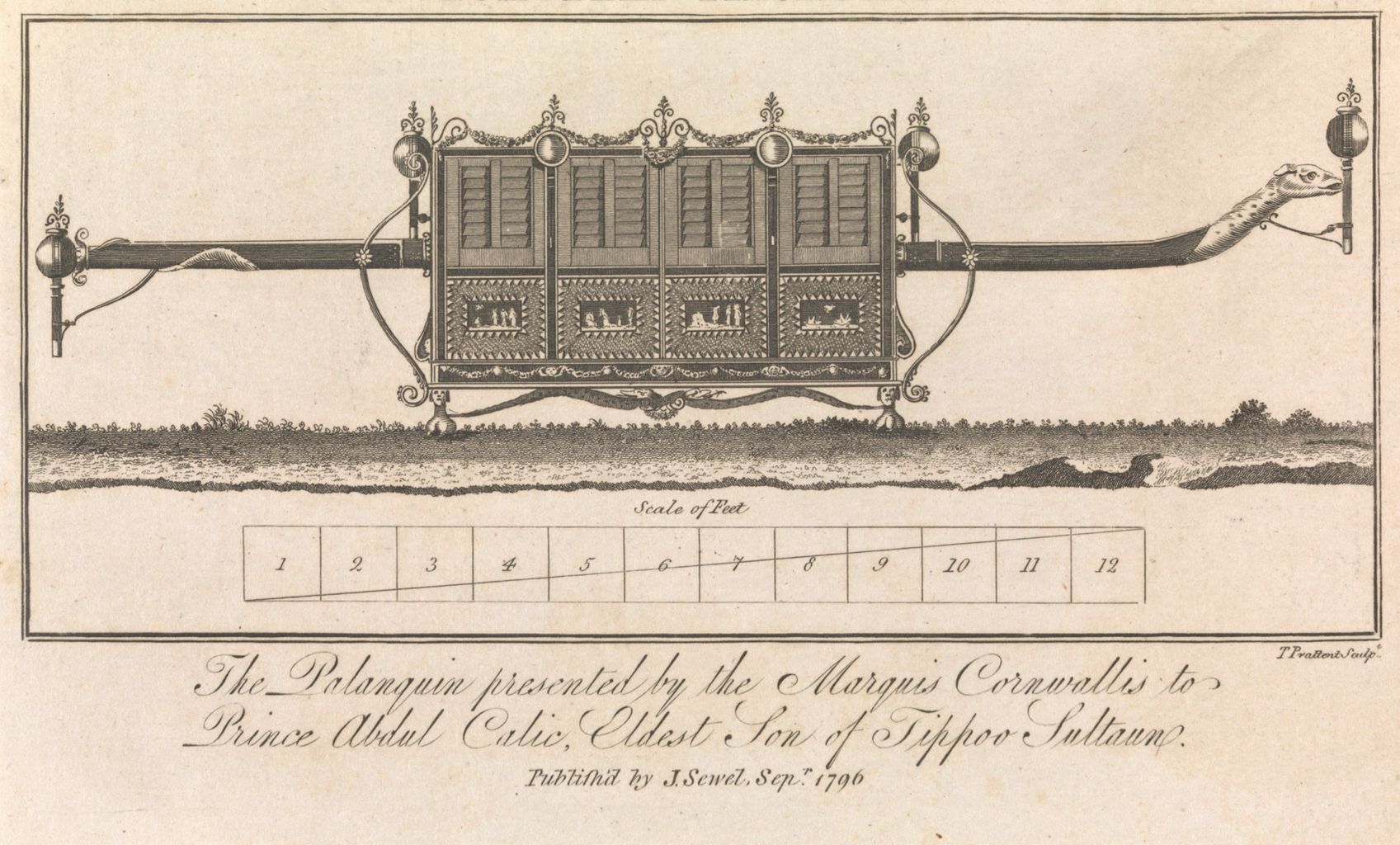

Steuart and Co. daysSolvyns devotes several plates to depicting various kinds of palanquins. Having been trained as a marine painter, he transferred some of those skills in Bengal by decorating palanquins—in European as well as Indian styles—which was a lucrative profession, when he was between commissions. Visible in the background of this image is possibly the edifice of Steuart and Co., Coach makers, the entrance to which features in another palanquin plate (The Long Palanquin). Upon his arrival in 1791, finding the art market less than lucrative with insecure prospects of commissions, Solvyns found employment as a decorator under Steuart & Co., and may have been the first European to be employed by them. By the mid-1790s, the British in Calcutta were moving from the congested areas around Tank Square to the airy suburbs of Garden Reach and Chowringhee. Solvyns, however, in 1794, resided in Old Court Lane, to the northwest of the Tank—behind the premises of Steuart & Co., coachmakers. |

Thomas Prattent

The palanquin presented by the Marquis of Cornwallis to Prince Abdul Calic, Son of Tippoo Sultaum

Robert Cooper, after John Alefounder

1821

|

The notion that the colonies allowed white men to enjoy social and political liberty and succeed according to their efforts irrespective of origin was widely held. Prospects were supposedly 'open to every subject of the Queen, though his father be as poor as Job...' But this egalitarian society existed only in willing suspension of disbelief. There were many poor and marginal Europeans in Calcutta and Bombay, whose miserable lifestyle struck the white ruling self with an embarrassing severity. They were rarely treated fairly by their brethren, the white ruling elite. The lavish lifestyles of officers and businessmen were nothing more than distant dreams for them, while decent jobs remained out of their grasp. |

|

|

|

Works cited Giles Tillotson, The Hindus: Baltazard Solvyns in Bengal, 2021, DAG

|

|

|