The Three Indian Illustrators of the Rubaiyat: A book transcending cultures and time

The Three Indian Illustrators of the Rubaiyat: A book transcending cultures and time

The Three Indian Illustrators of the Rubaiyat: A book transcending cultures and time

collection stories

|

The Rubaiyat of Omar Khayyam by Edward FitzGerald is an anthology of four-line verses first published in 1859. The poems were inspired by Persian quatrains credited to Omar Khayyam (1048-1131), which became a global phenomenon at the turn of the twentieth century. The first edition of FitzGerald’s Rubaiyat has been uniquely published over 3700 times, and the verses translated over 1000 times. The DAG Archives host three different editions of the Rubaiyat with illustrations by Abanindranath Tagore, Mahadev Vishwanath Dhurandhar and Mera Ben Kavas Sett, allowing us the opportunity to study the publication and its different interpretations. Even though the technique employed by each artist differs drastically, they all illustrated the 1859 first edition of the Rubaiyat. |

|

|

Who was Omar Khayyam?Omar Khayyam was an 11th-12th century Persian mathematician and astronomer. He created the Jalali calendar, a version more accurate than the later Gregorian counterpart (1582) we use today. Khayyam was only a minor poet in his life, but FitzGerald’s verses made him extraordinarily popular. Deeply philosophical, the four-line verses or rubai emphasise the fleeting nature of human life, where death is not an end but a process of regeneration. Among many epithets, we find his reverence for dust. The poet claims dust is everything that once was around us—among them the noblest of rulers and the most precious stones—and therefore should be treated with care. |

Authorship of the Rubaiyat

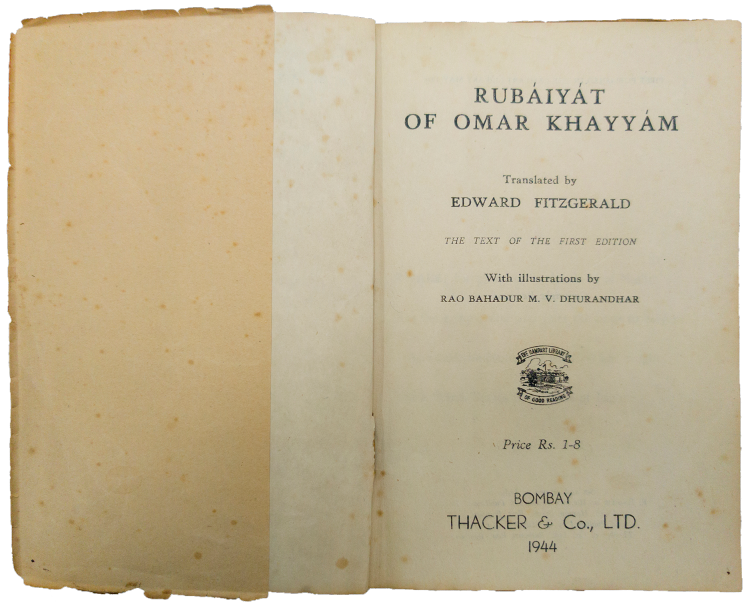

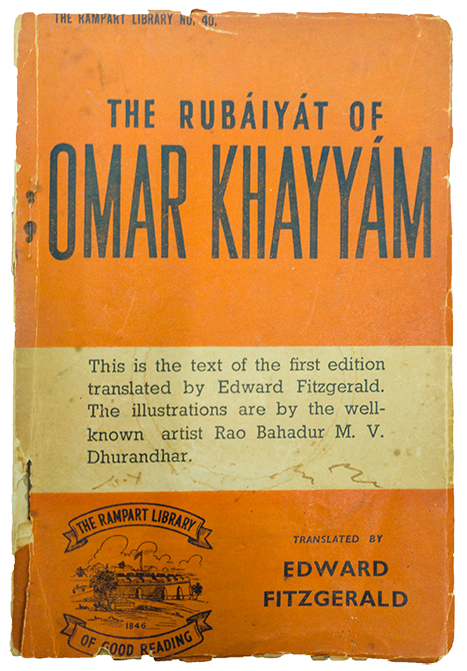

M. V. Dhurandhar

Rubaiyat of Omar Khayyam

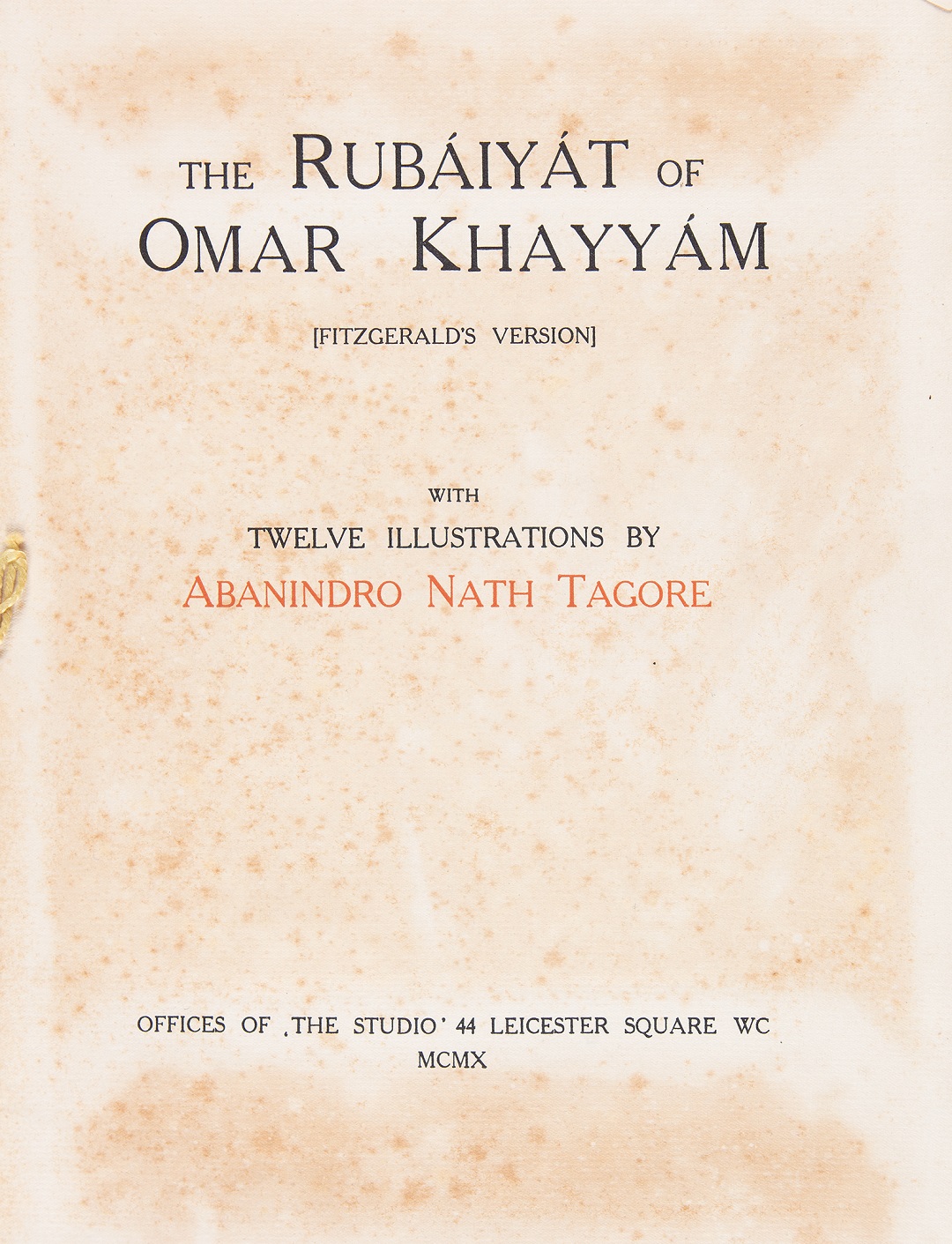

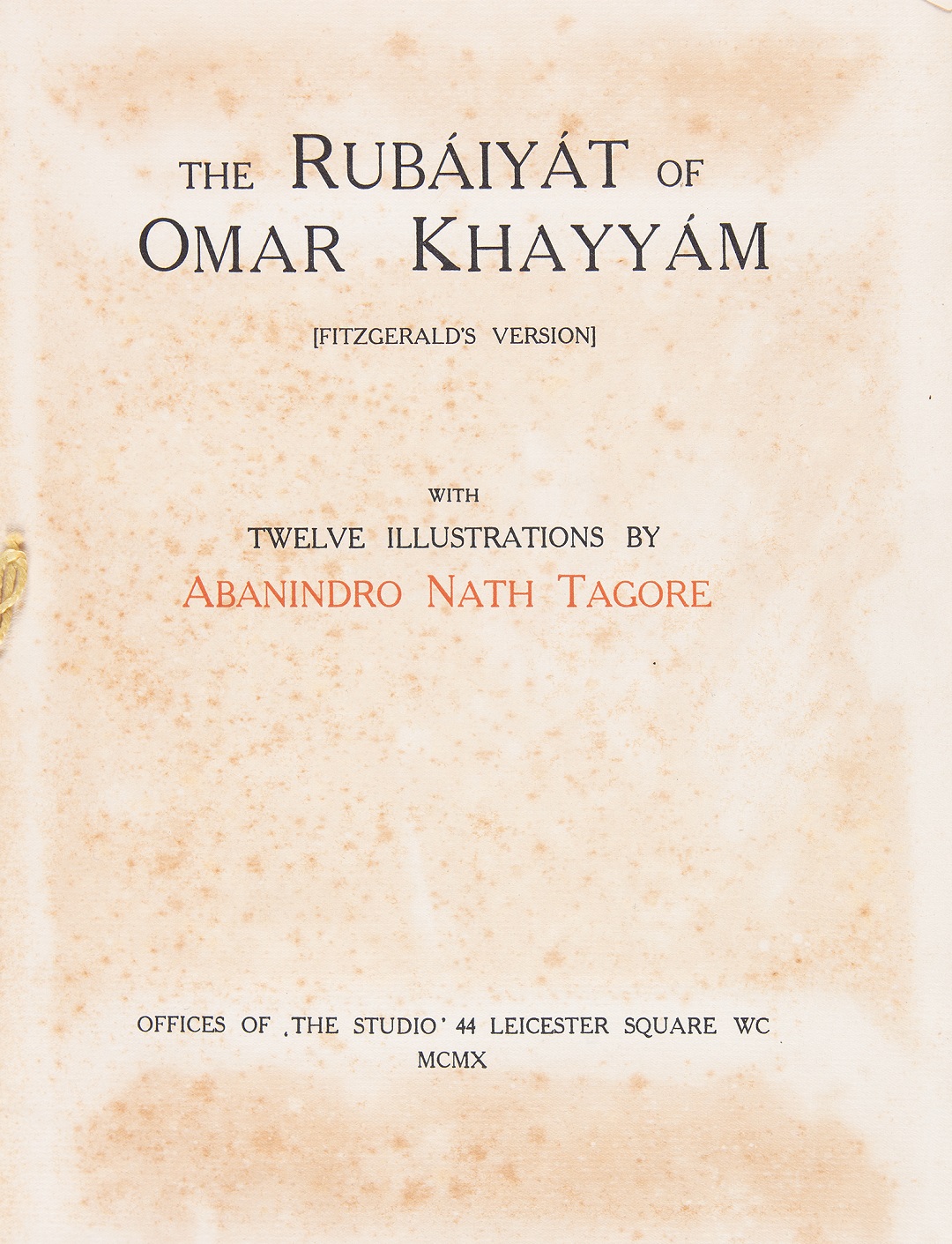

Abanindranath Tagore

Rubaiyat of Omar Khayyam

Many editions—including the version carrying M. V. Dhurandhar’s illustrations—identify FitzGerald as a ‘translator’, whereas contemporary scholarship has revealed that not only did his verses carry different meanings, a significant quantity of the poems were not penned by Omar Khayyam, but later poets who followed the Khayyami style.

|

Omar Khayyam’s Rubaiyat, But as FitzGerald Saw it Fit Edward FitzGerald (1809-83) reimagined the rubai as fit for his contemporary English audience. While composing, he used the iambic pentameter rhyming scheme in 'aaba' pattern (where the first, second, and fourth lines rhyme). FitzGerald published the 1859 edition as an assortment of quatrains but reorganised them in following editions to create a narrative structure like a sonnet or lyric poem. In its title, FitzGerald identified Omar Khayyam as the originator of the rubai, but his was a greatly inspired reimagination, with many liberties taken to make the verses more accessible to his contemporary Victorian English-speaking readers. Their immense popularity led to the rediscovery of Persia’s short-format Khayyami poetry, along with hitherto unknown poets who shared Khayyam’s structure of composing. |

|

|

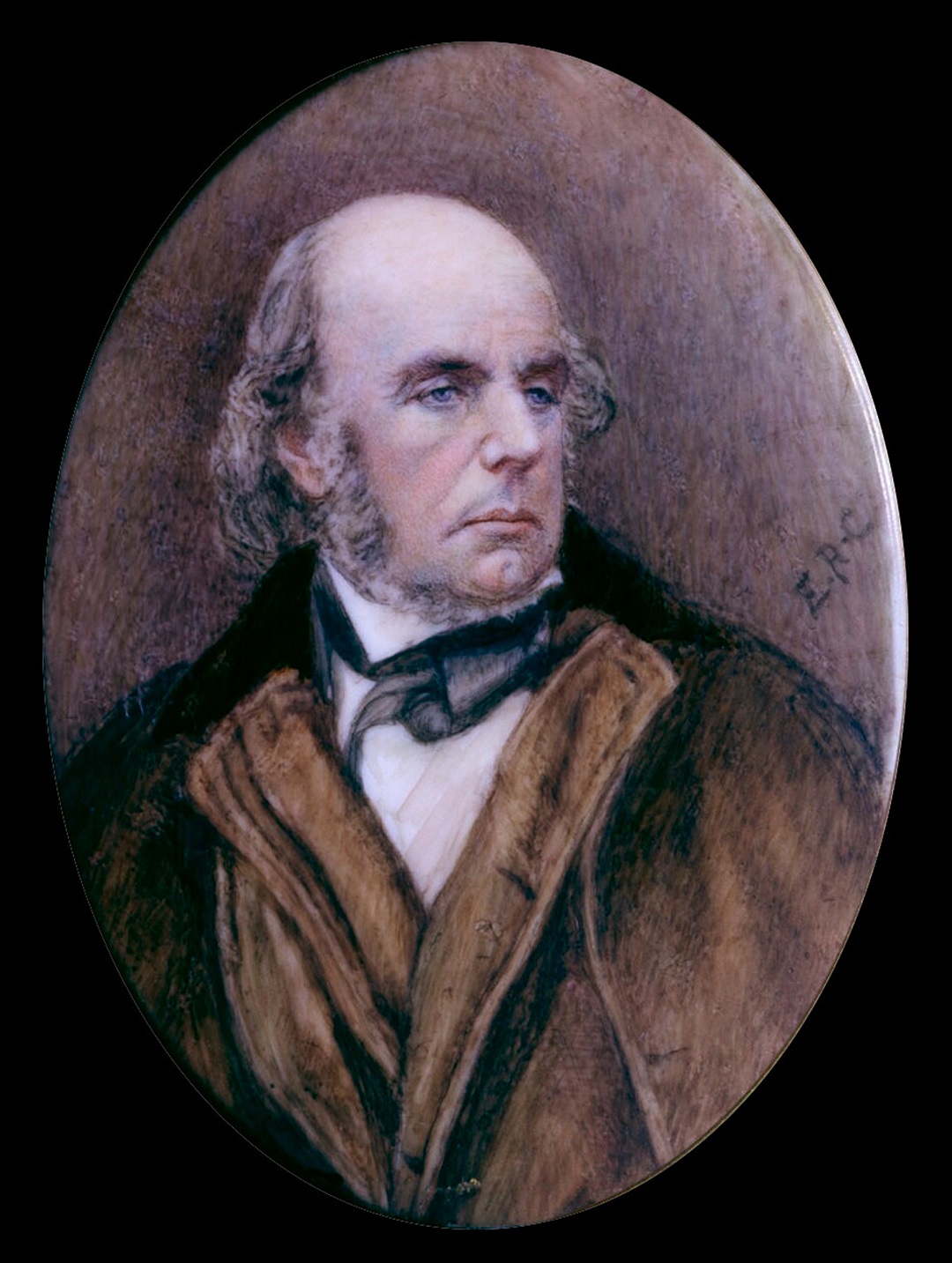

Eva Rivett-Carnac

Miniature portrait of Edward FitzGerald by Eva Rivett-Carnac (DoB Unknown-1939) after a photograph of 1873

Watercolour on ivory

Collection: National Portrait Gallery, London, Public Domain

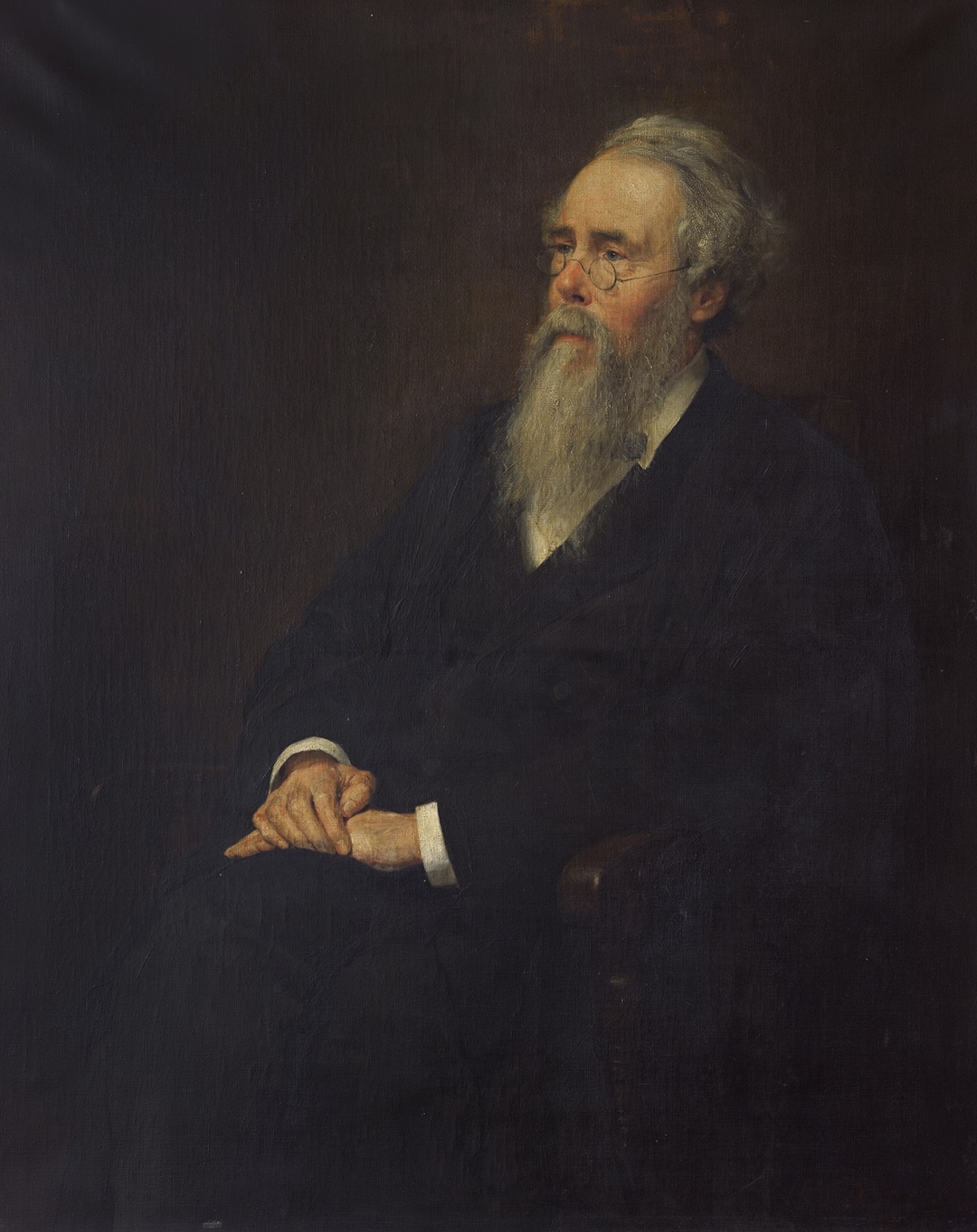

Charles Edmund Brock

Portrait of Edward Byles Cowell (1826-1903)

Oil on canvas

Collection: Corpus Christi College, Cambridge University, Public Domain

India Connection to the RubaiyatFitzGerald was friends with Edward Cowell, a Victorian Englishman in India who could read and write Persian. Cowell came across a manuscript containing 158 short-format Persian verses at Oxford’s Bodleian Library, which was taken by FitzGerald as a primary source of the English Rubaiyat. When FitzGerald was writing the first edition during 1857-59, Cowell was teaching at Presidency College, Calcutta, as a professor of English History. He found a second document, famously labelled the ‘Calcutta manuscript’, containing 516 verses at the city’s Asiatic Society library, and sent it over to FitzGerald. While FitzGerald ended up using some of the verses from this manuscript, its authenticity has been highly contested. |

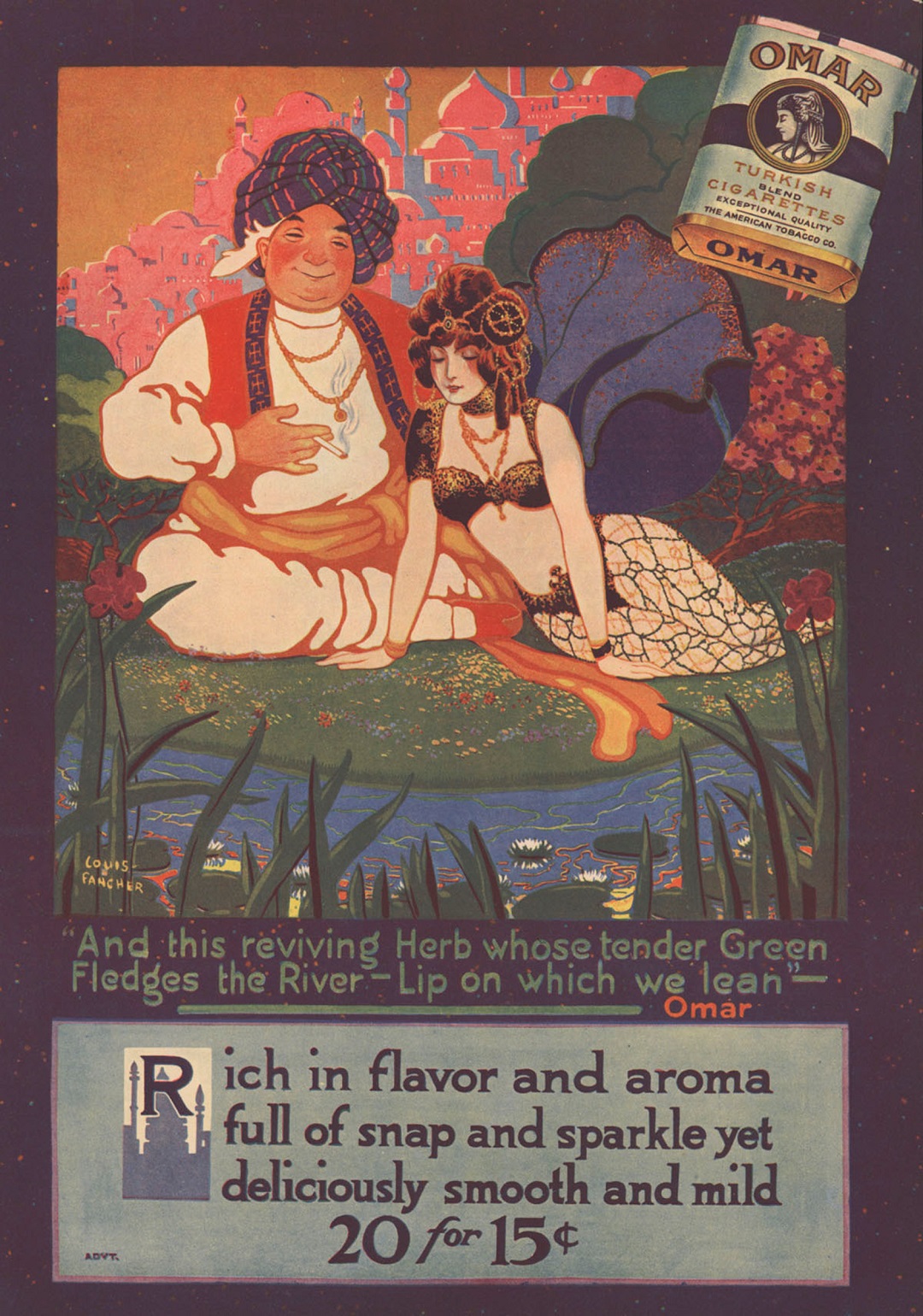

Advertisement for Omar Turkish Cigarettes by American Tobacco Company

Printed Advertisement

1910

Collection: Stanford Research into the Impact of Tobacco Advertising

The Rubaiyat became a global phenomenon towards the end of the nineteenth century. In 1892, the Omar Khayyam Club was founded in his and FitzGerald’s honour, and continues to function today. Even consumer items—tooth powder, perfume and tobacco products—shared the Persian poet’s name due to his immense popularity. The concluding phrase from the book, ‘tamam shud’ (meaning, ‘it is ended’) is also associated with an unsolved Australian mystery dating back to 1948. |

|

Indian Artists Imagining the Rubaiyat Like elsewhere in the world, the Rubaiyat was a popular publication in twentieth century India, and among the many versions available to us, a Hindi translation was penned by Harivansh Rai Bachchan. Due to its fame, illustrations were commissioned to complement new publications. The three illustrators—Abanindranath Tagore, M. V. Dhurandhar, and M. K. Sett—selected for this comparison showcase different ways these interactions occurred. |

|

|

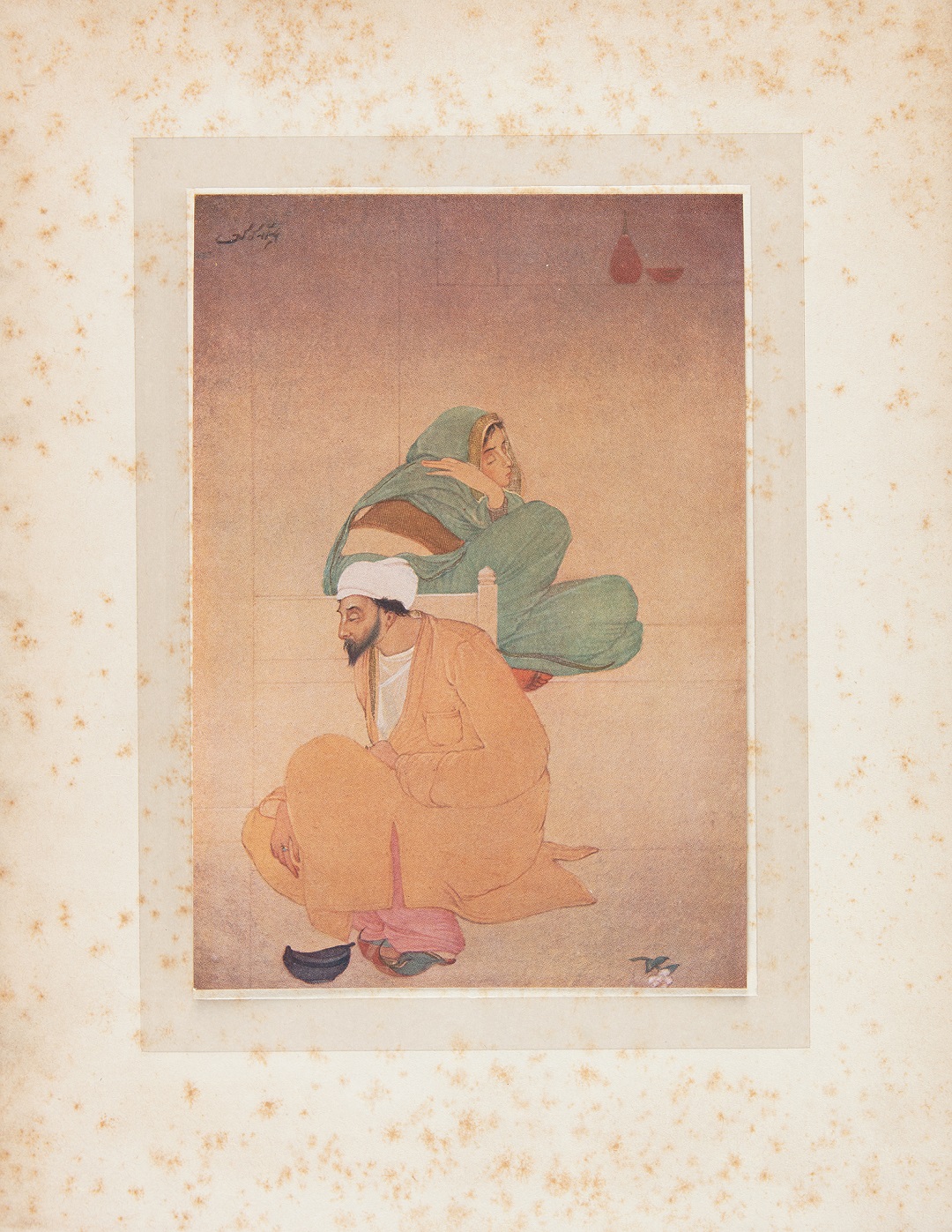

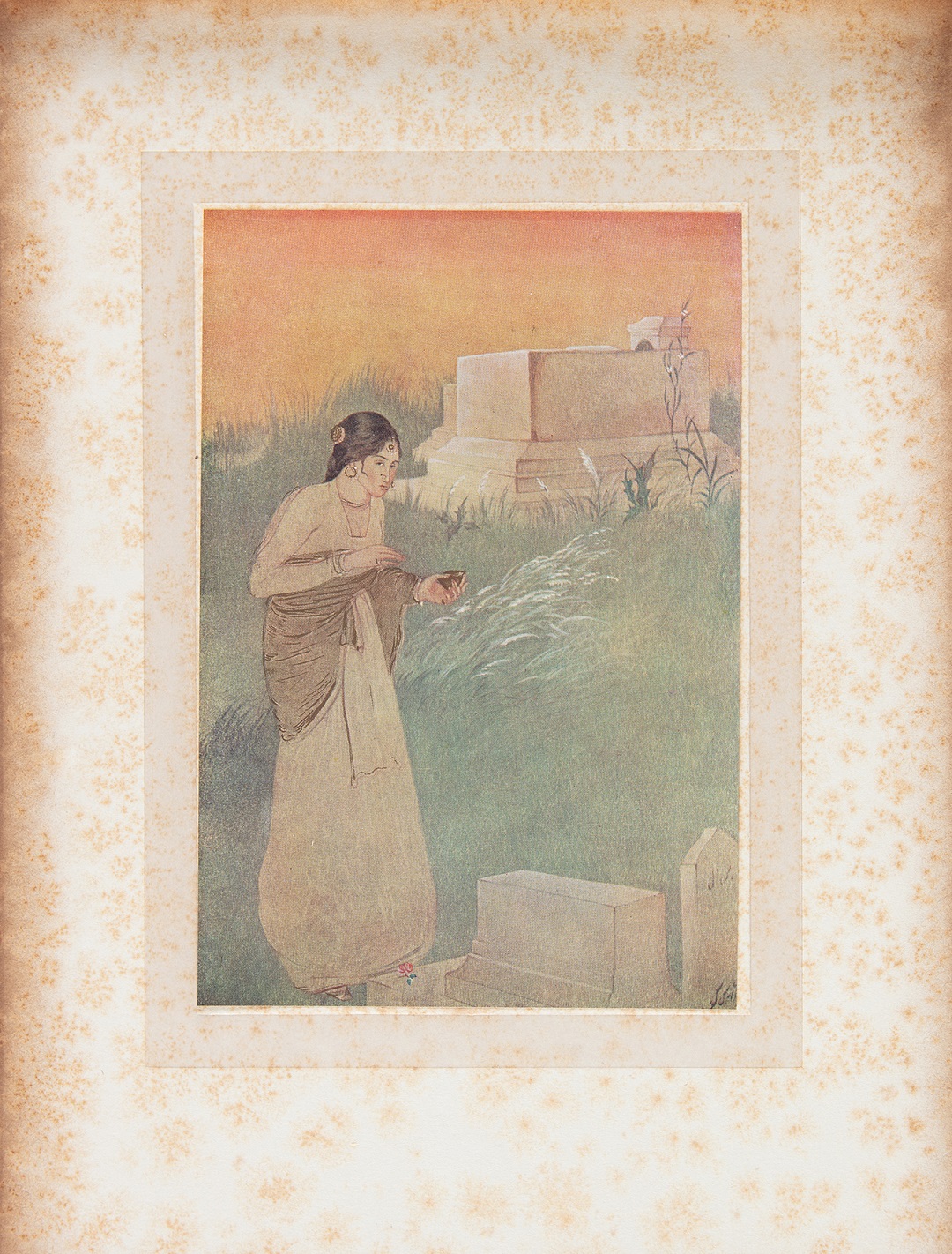

Abanindranath TagoreAbanindranath Tagore (1871-1951) is one of India’s nine National Art Treasure artists. An artist and teacher associated with Calcutta’s Government College of Art and Craft and Santiniketan’s Visva-Bharati University, he was the founder of the anti-colonial art movement is now identified as the Bengal School. |

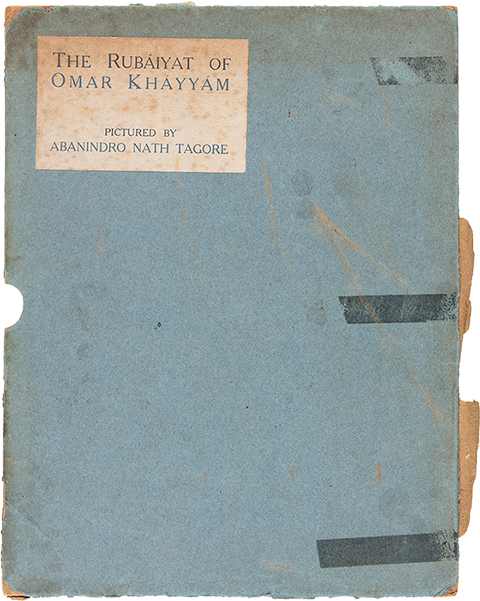

Abanindranath Tagore

Rubaiyat of Omar Khayyam

Abanindranath Tagore

Rubaiyat of Omar Khayyam

Abanindranath Tagore

Rubaiyat of Omar Khayyam

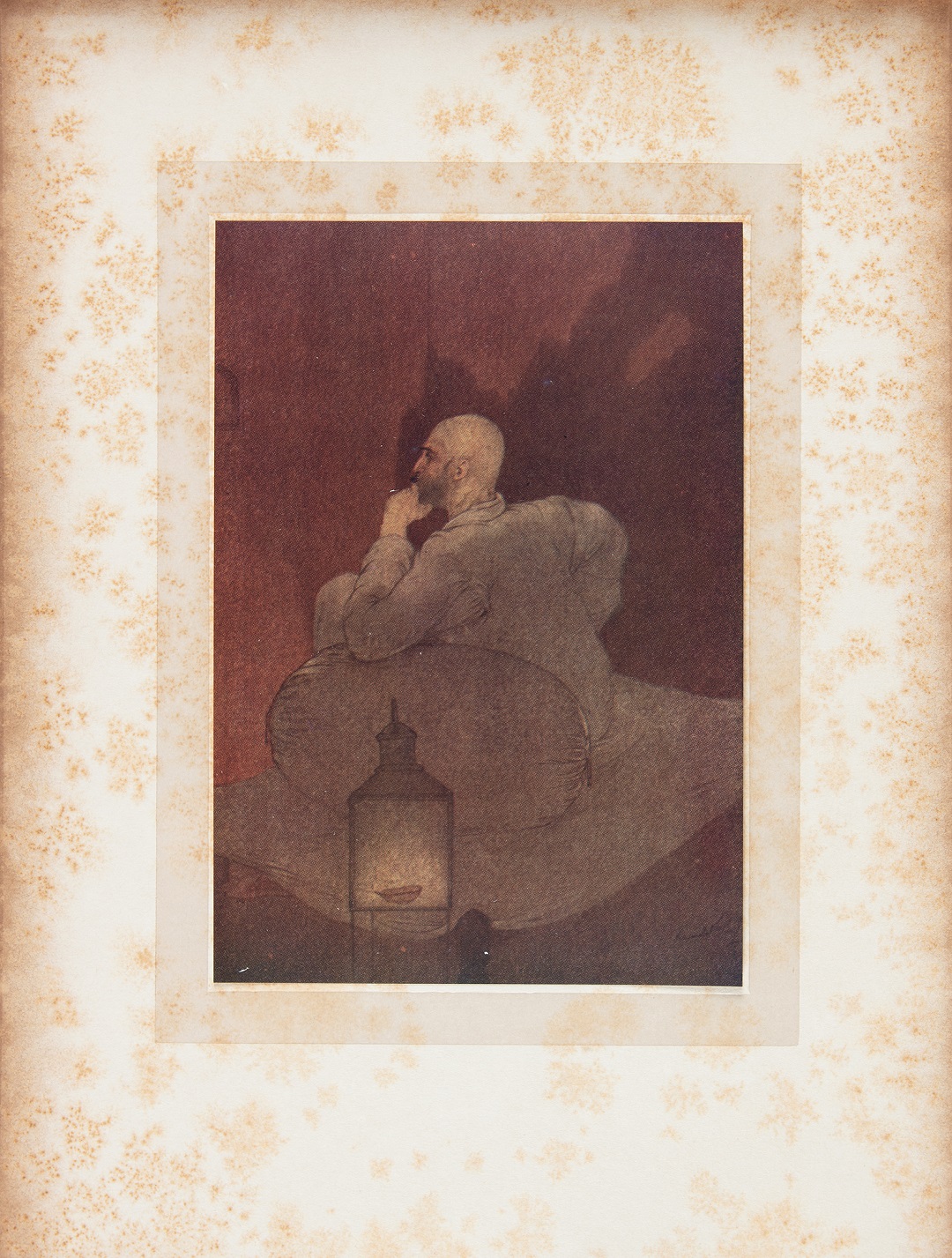

In 1910, a year after the famous Edward Dulac plates were published by Hodder & Stoughton, Eyre & Spottiswoode brought out the Rubaiyat with twelve illustrations by Abanindranath Tagore, curiously with his name spelt ‘Abanindro Nath’ on the cover. The illustrated plates were printed on glossy paper and mounted on embossed cardstock. These were ‘tipped-in’ pages, printed separately from the text of the book. To protect the metallic gold highlights on the images, glassine sheets were added—which also carry the corresponding rubai.

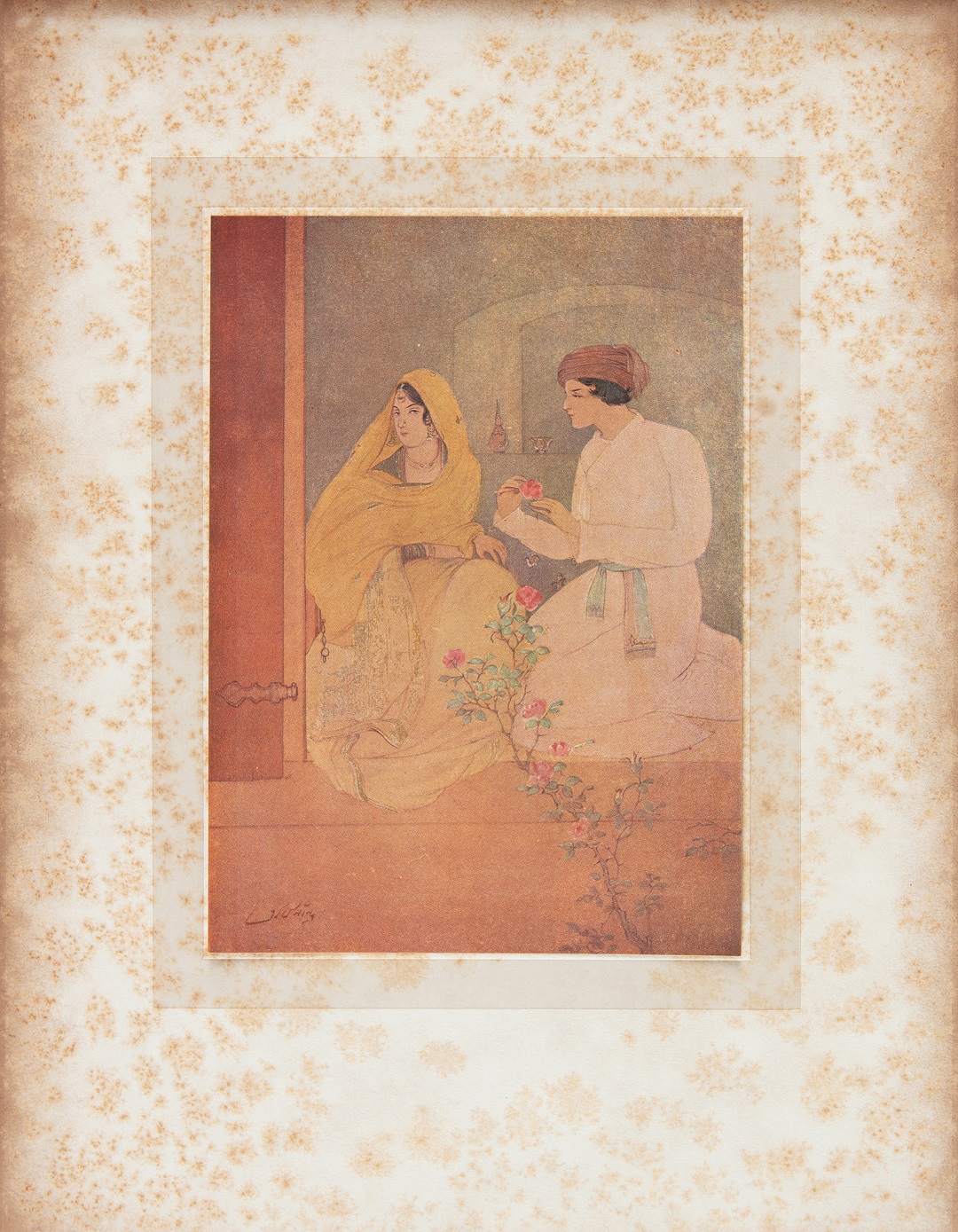

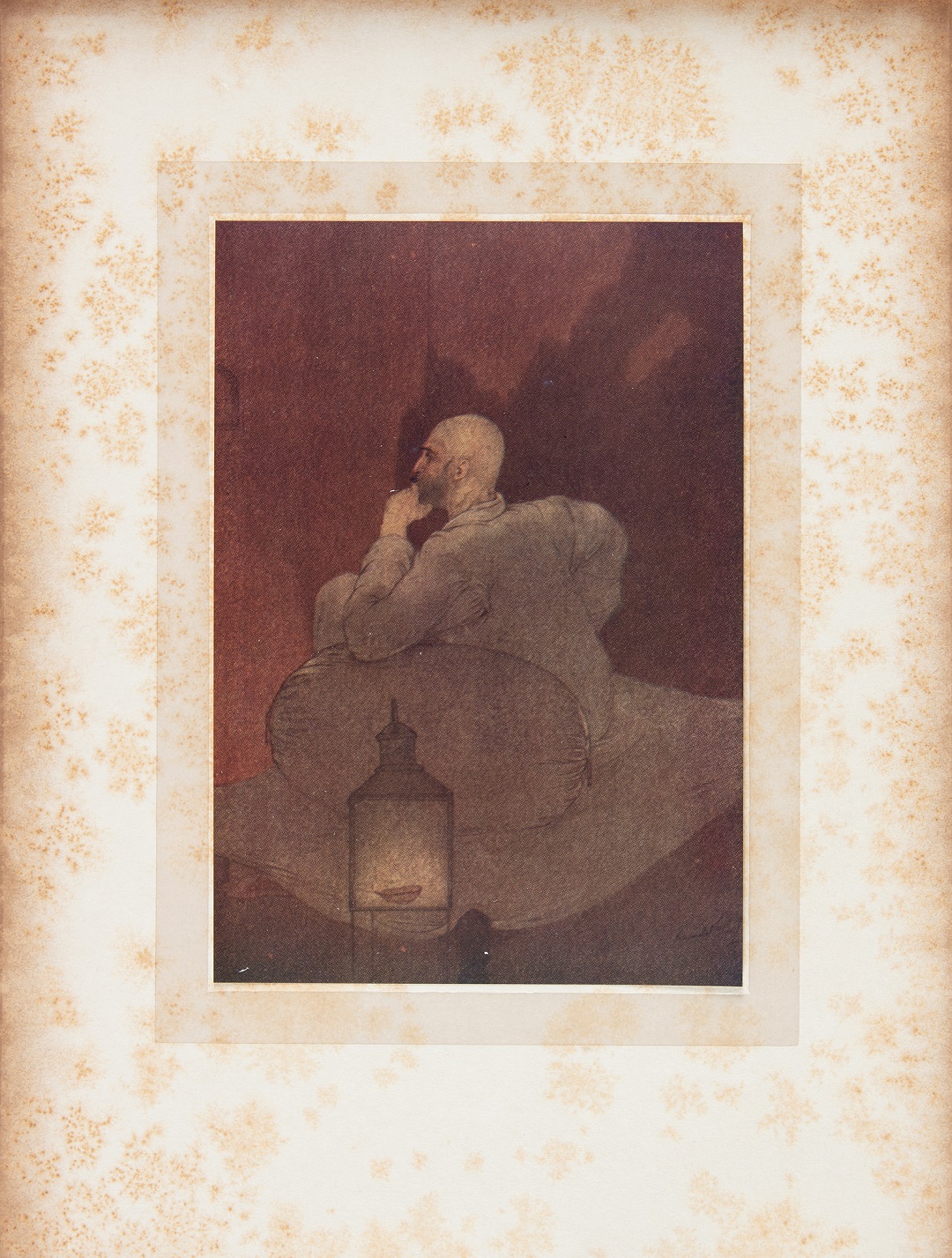

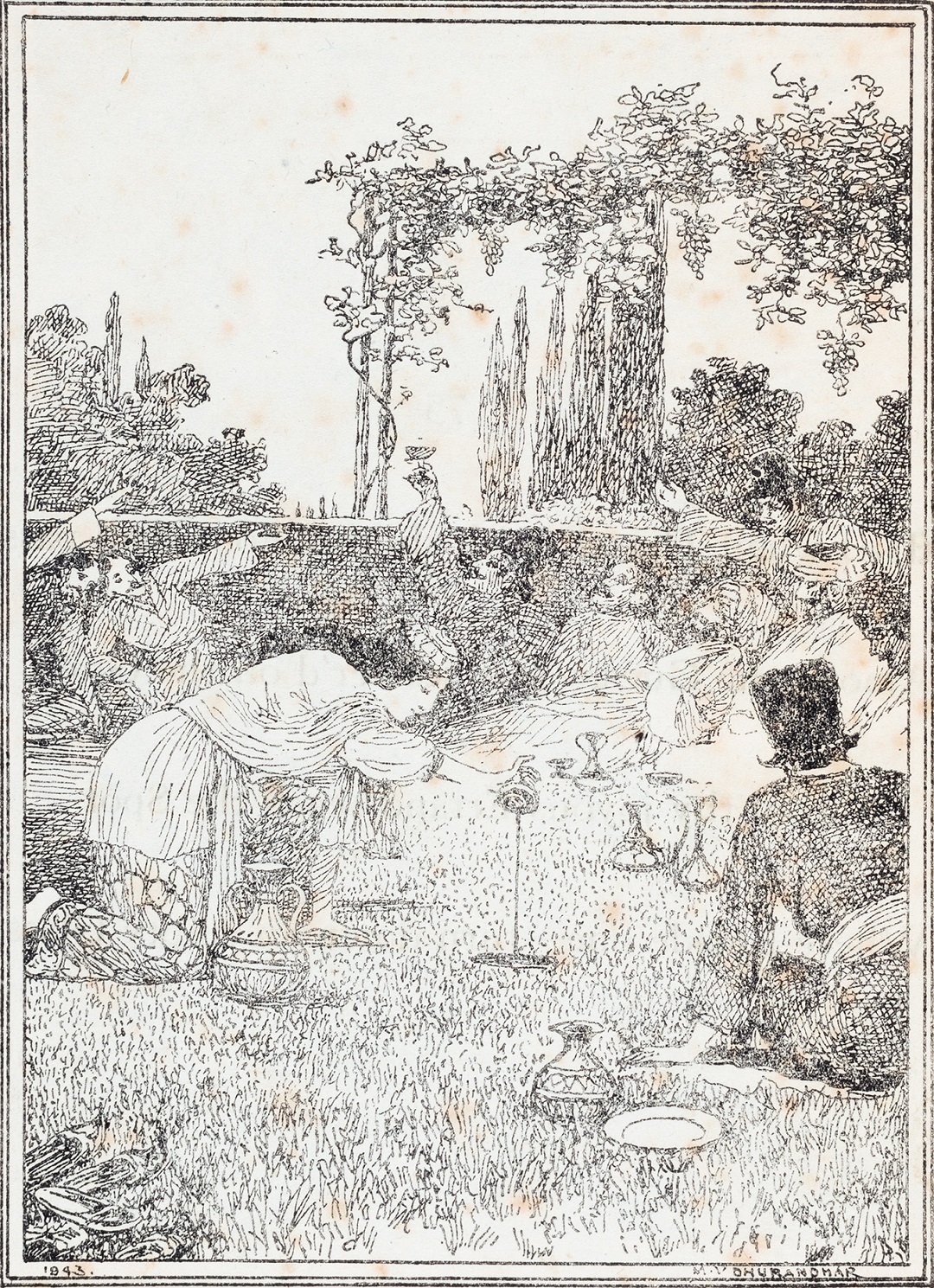

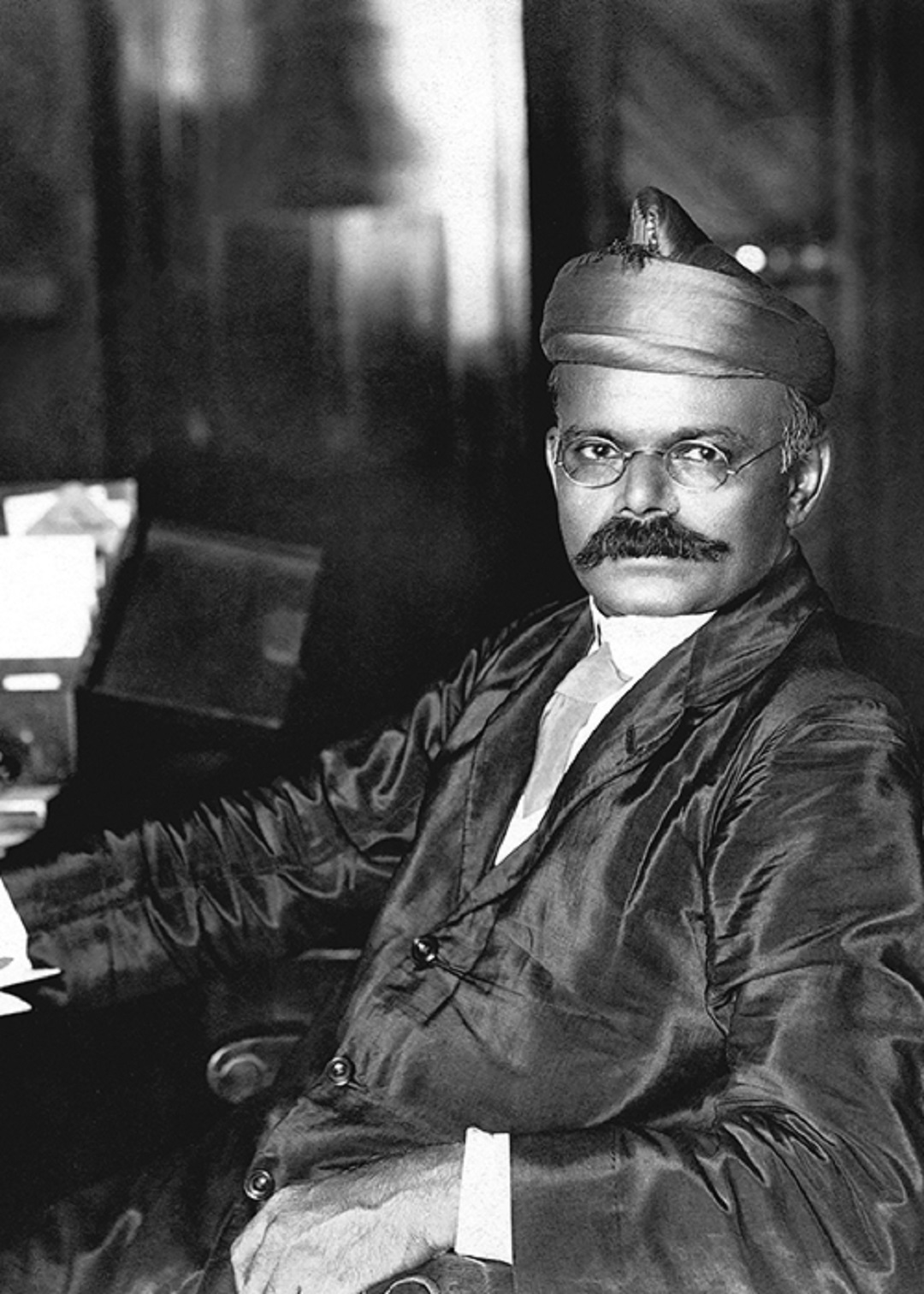

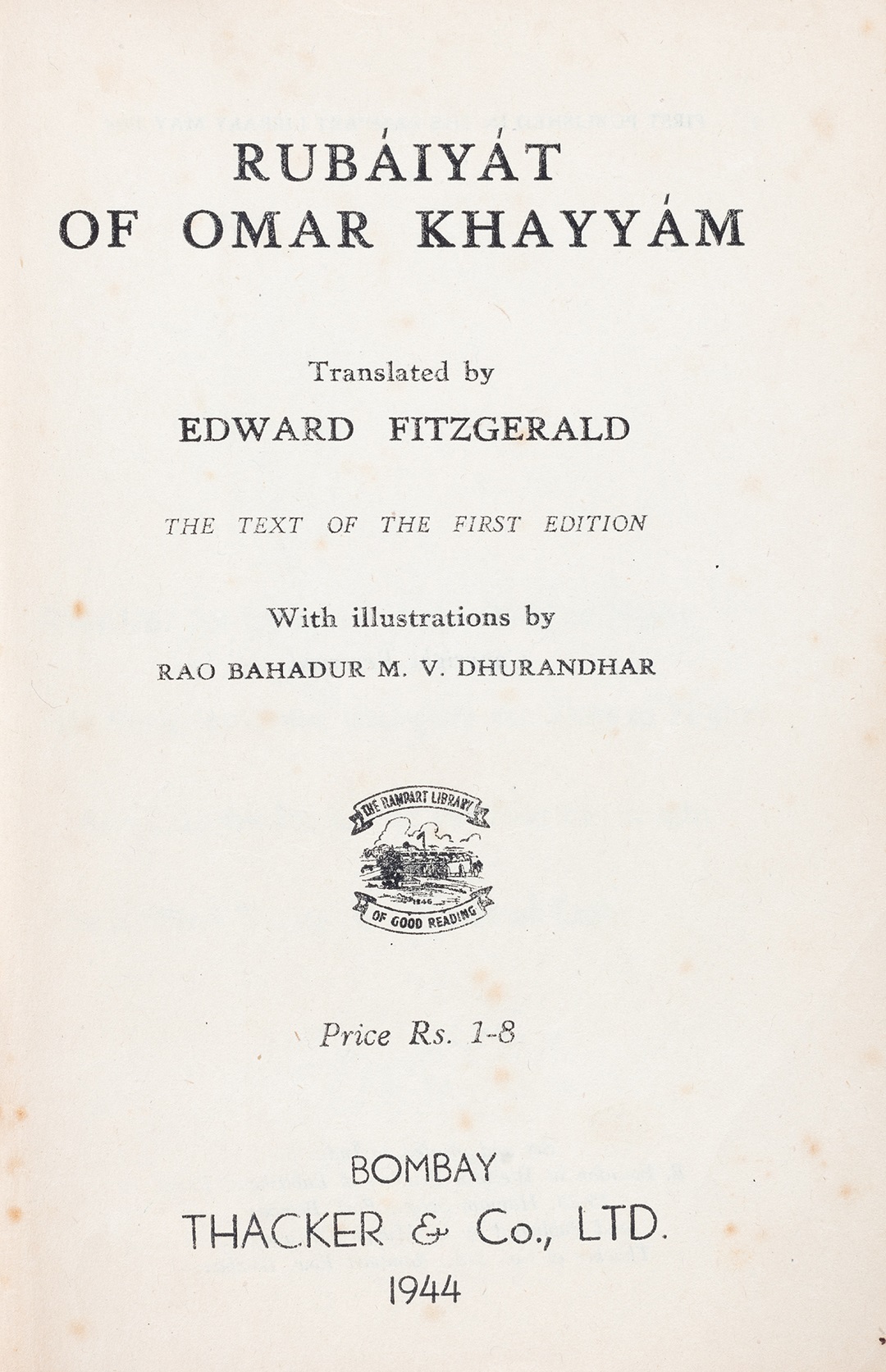

M. V. DhurandharPossibly the most popular academic Indian artist after Raja Ravi Varma, Kolhapur-born Rai Bahadur M. V. Dhurandhar (1867-1944) was associated with Bombay’s Sir J. J. School of Art. Dhurandhar joined the institution after graduating as an art teacher and gradually ascended different administrative ranks. At the end of a long and illustrious teaching career, he became the school’s first Indian Director in 1930. |

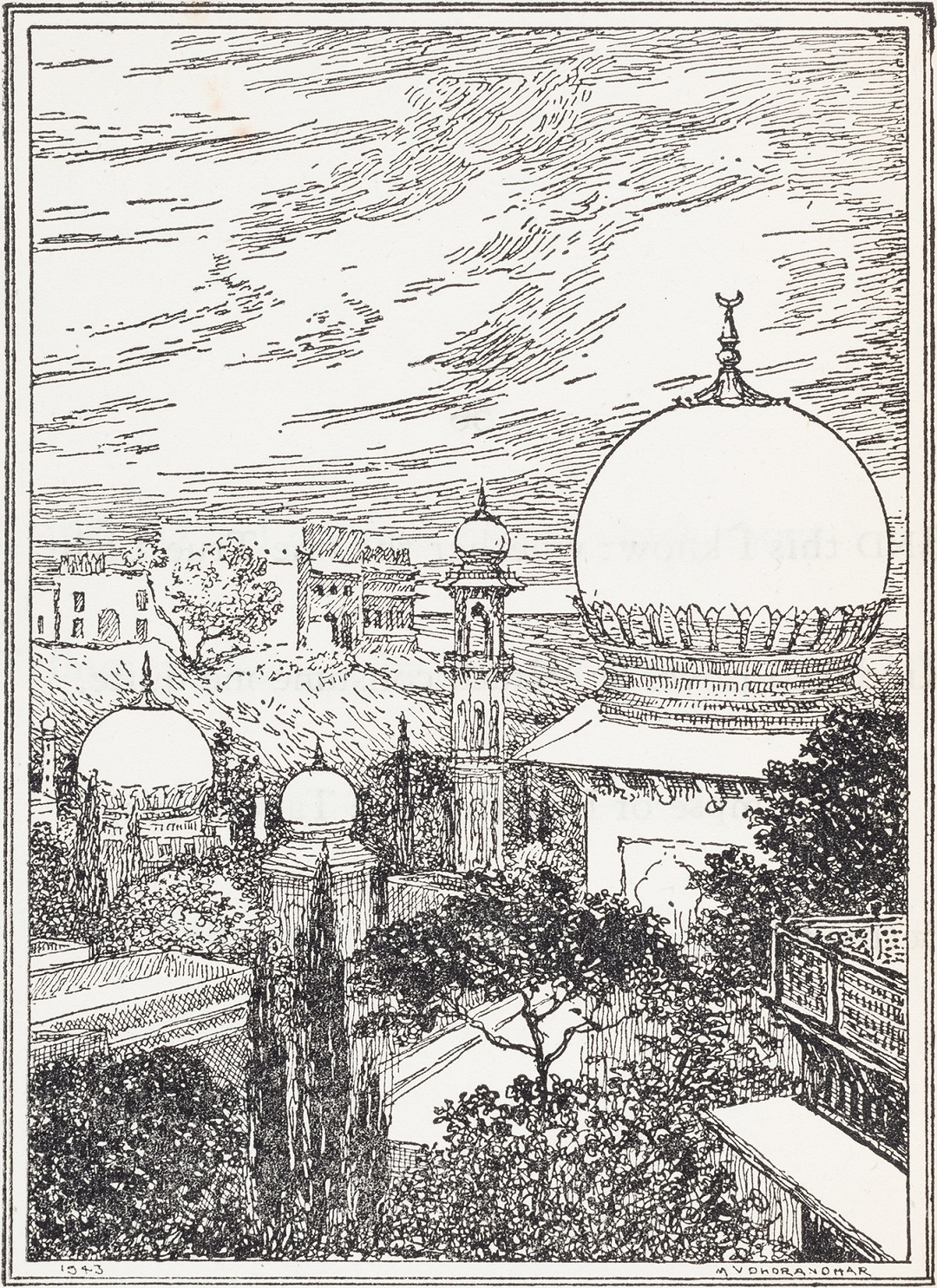

M. V. Dhurandhar

Rubaiyat of Omar Khayyam

1944

Print on paper, paperback

M. V. Dhurandhar

Rubaiyat of Omar Khayyam

1944

Print on paper, paperback

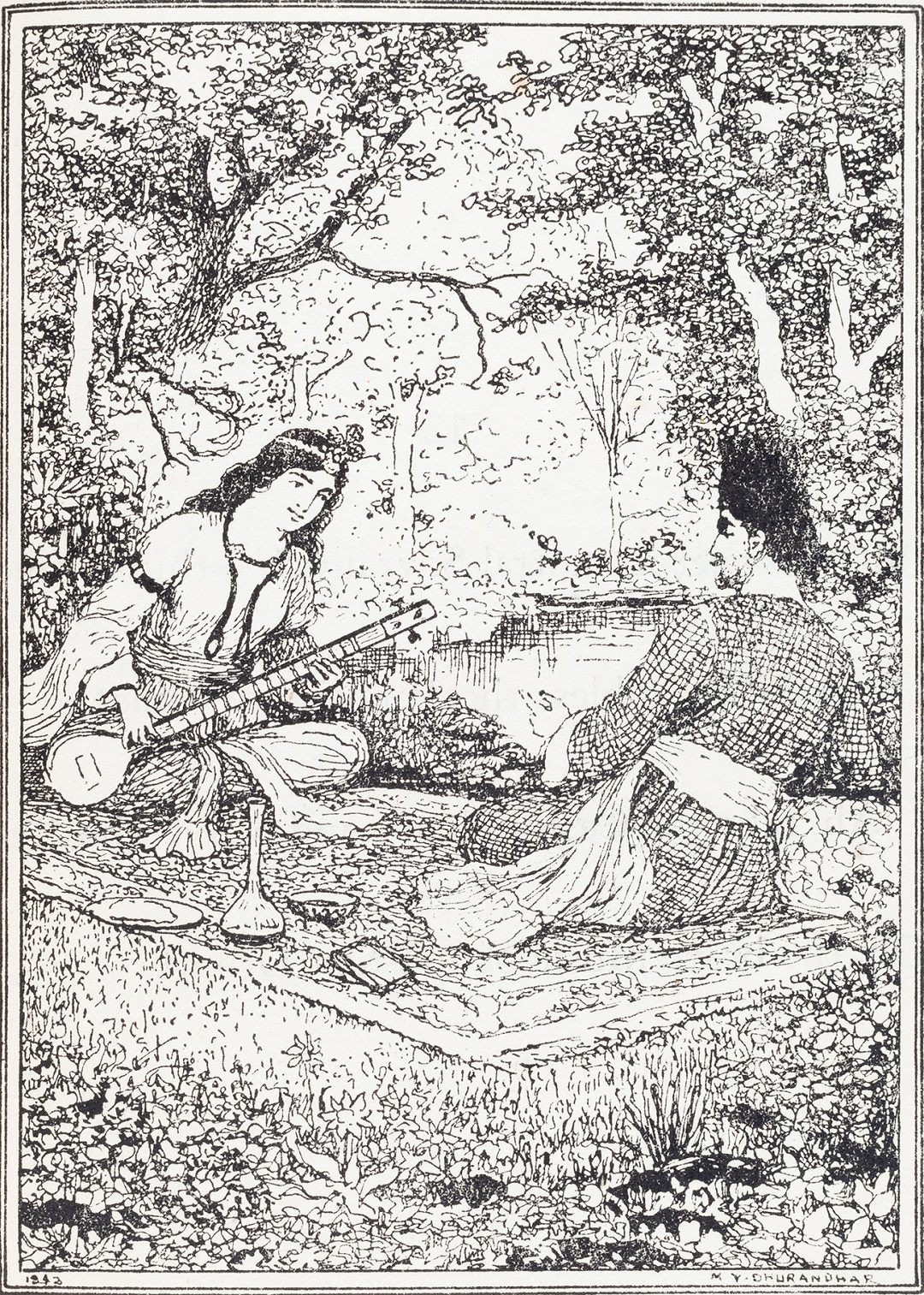

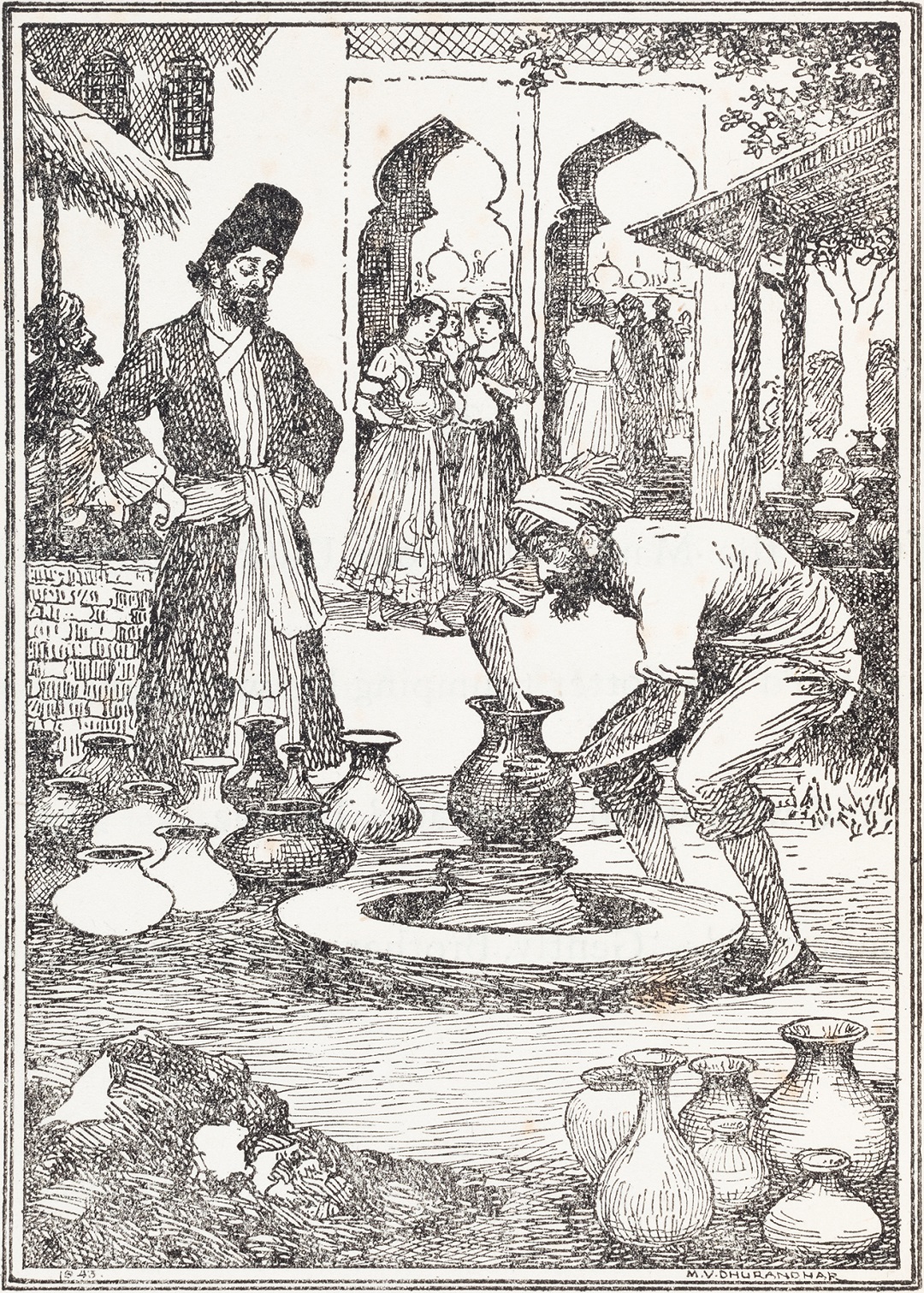

M. V. Dhurandhar

Rubaiyat of Omar Khayyam

1944

Print on paper, paperback

M. V. Dhurandhar’s single-tone images were published by Bombay Thacker & Co. in 1944—incidentally, the year of his death. Priced ‘Rs. 1-8’ (one rupee and eight annas), it contains eighteen illustrations in black ink. Each engraved image is accompanied by an excerpt from the rubai that inspired it. |

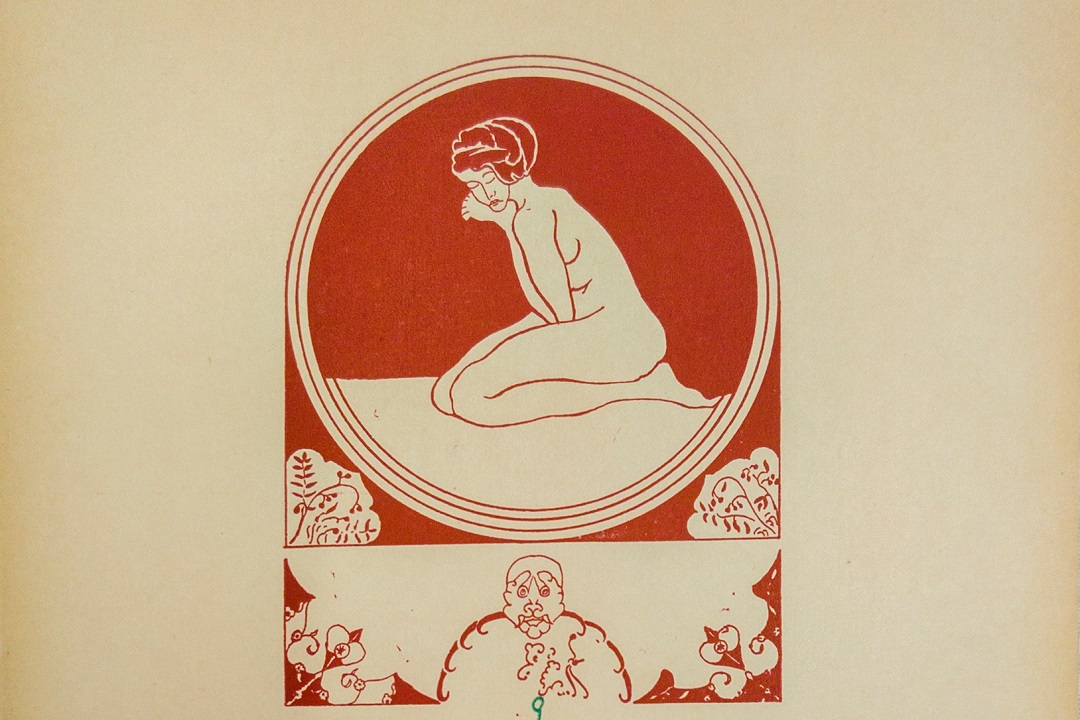

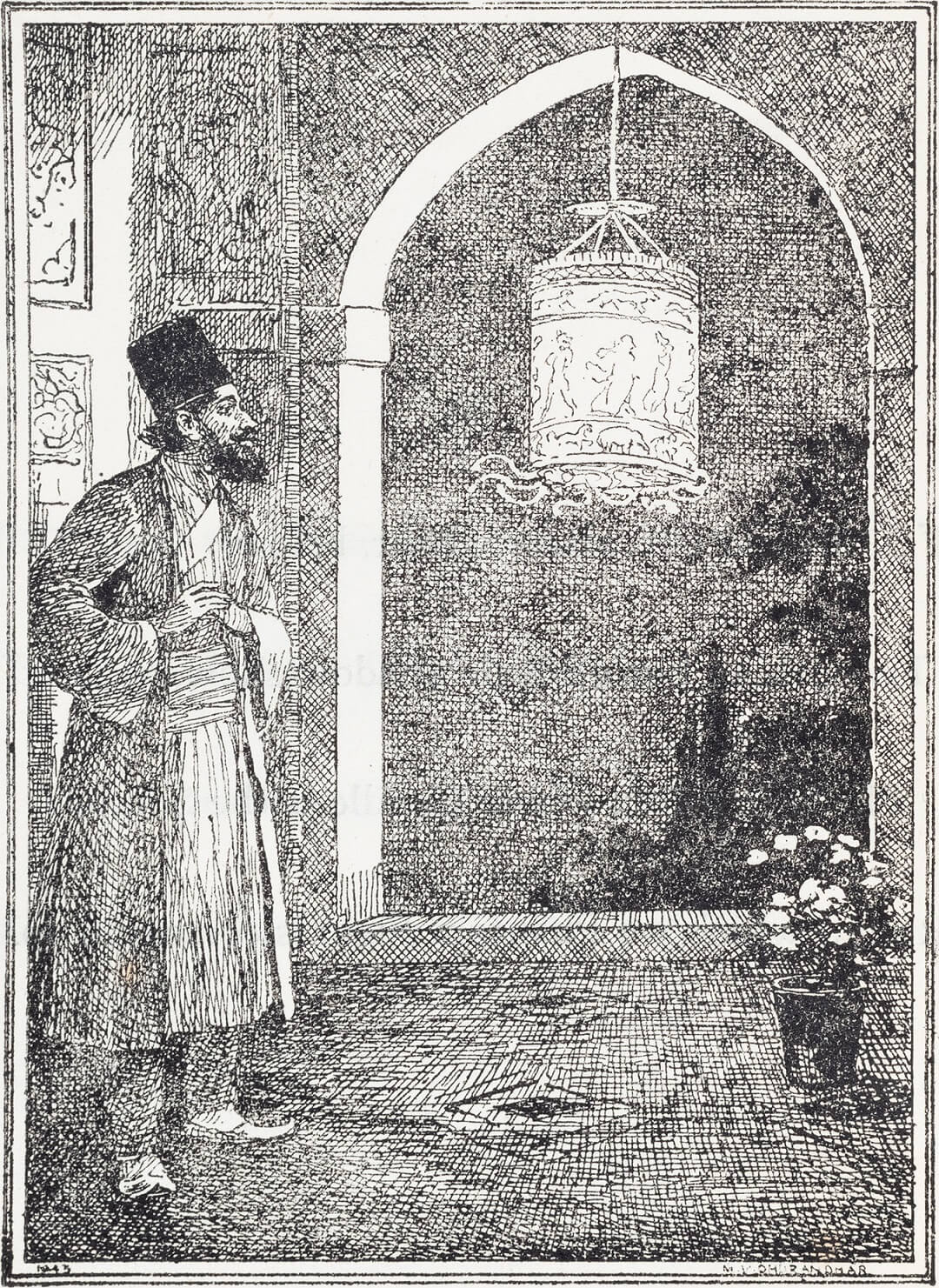

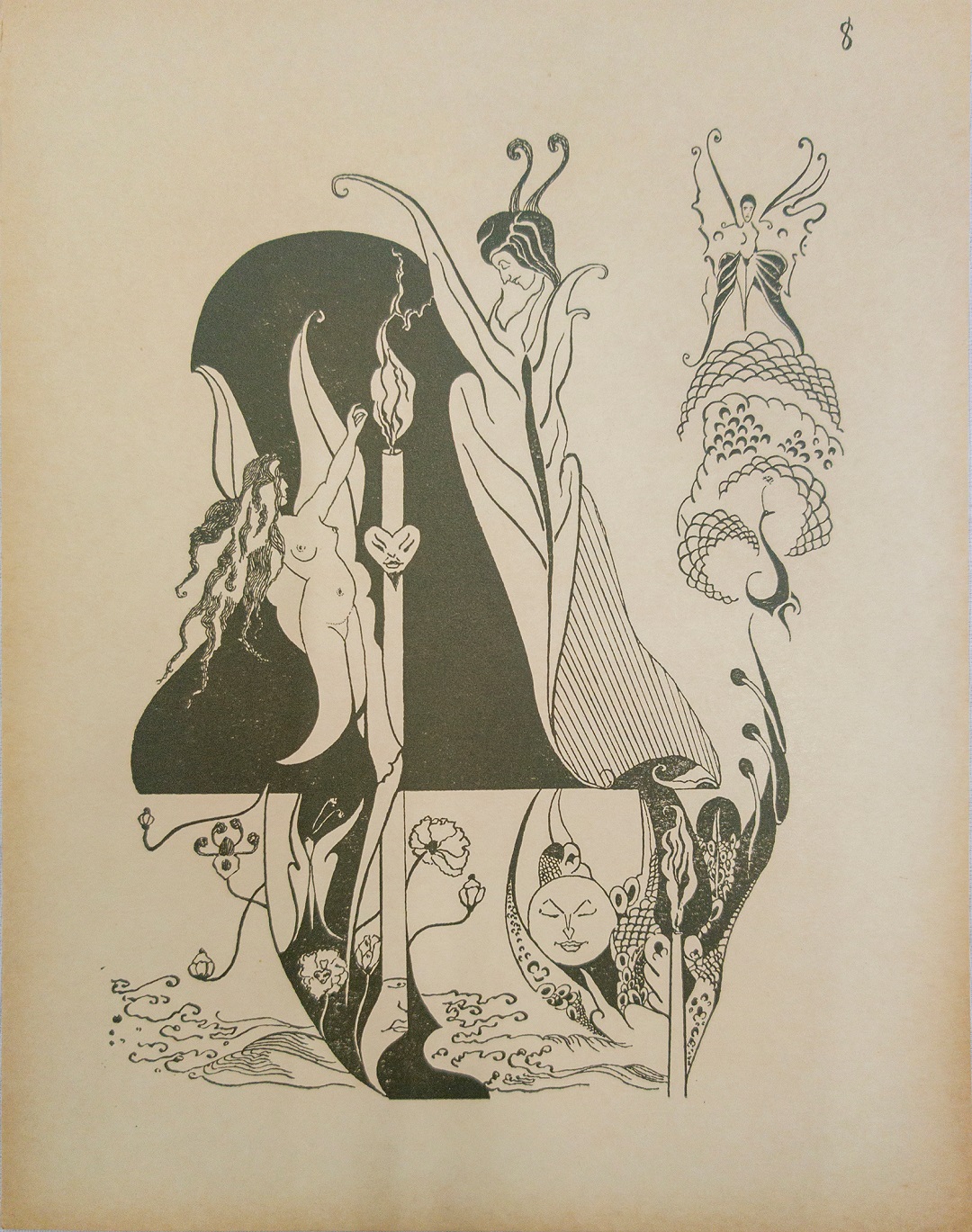

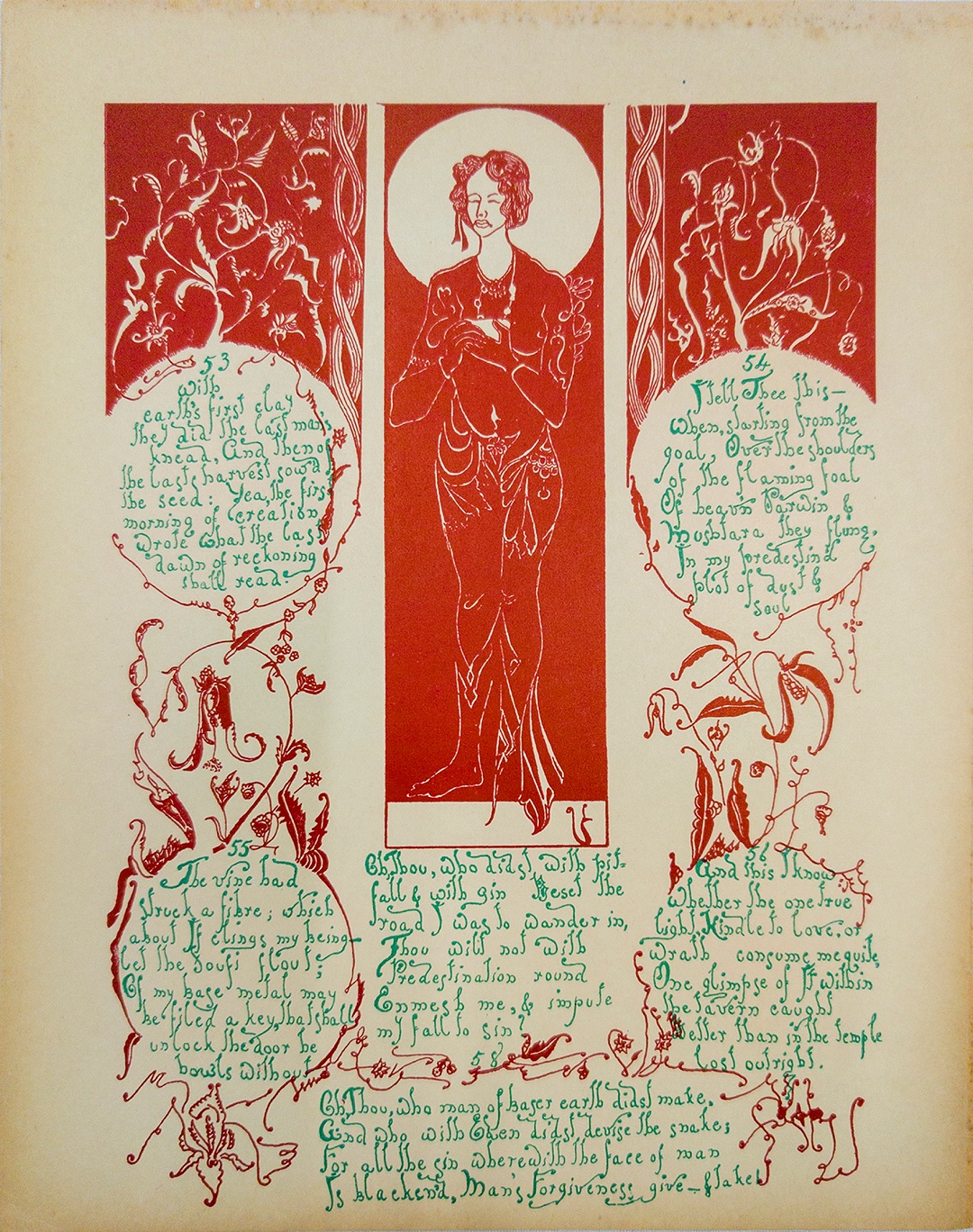

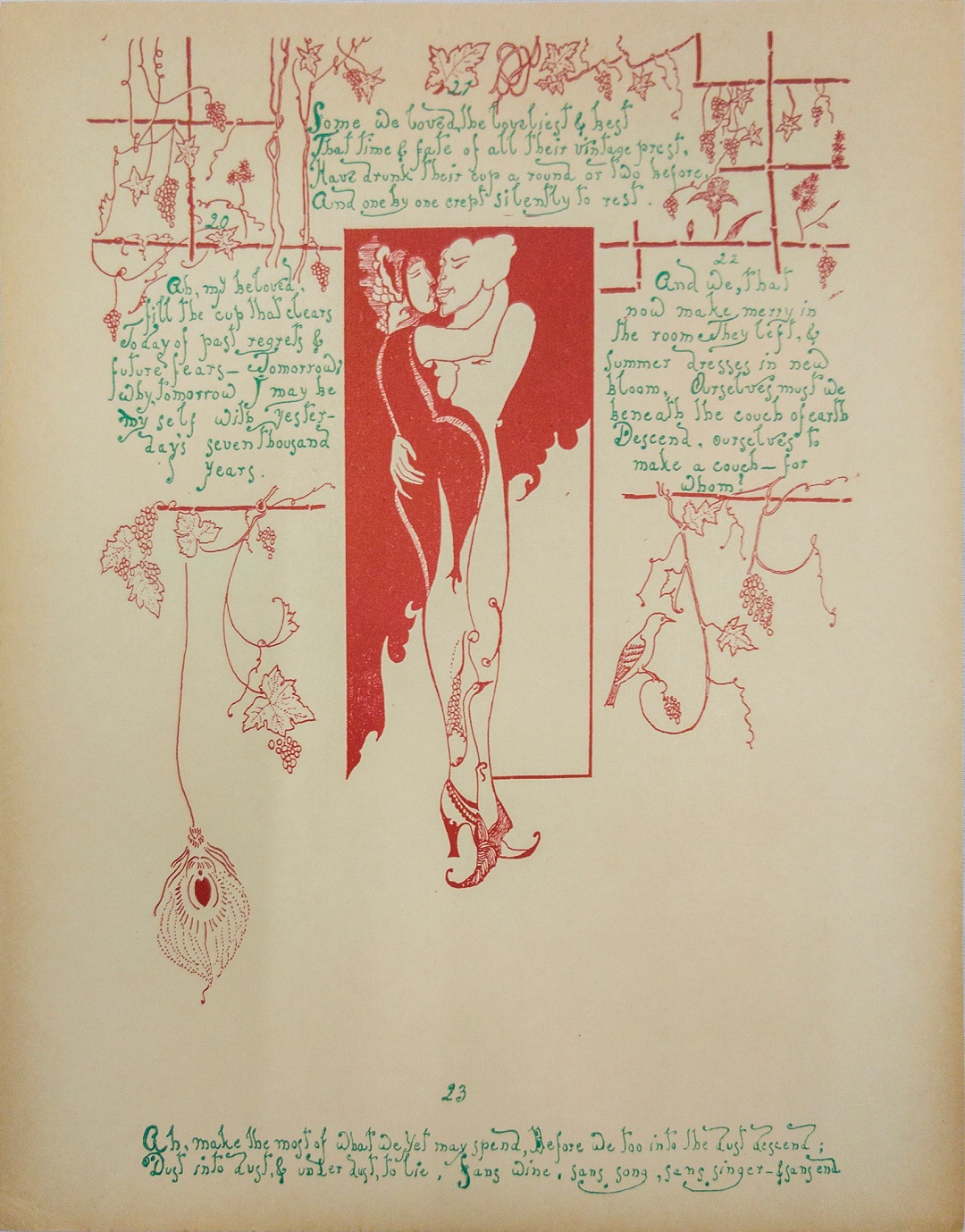

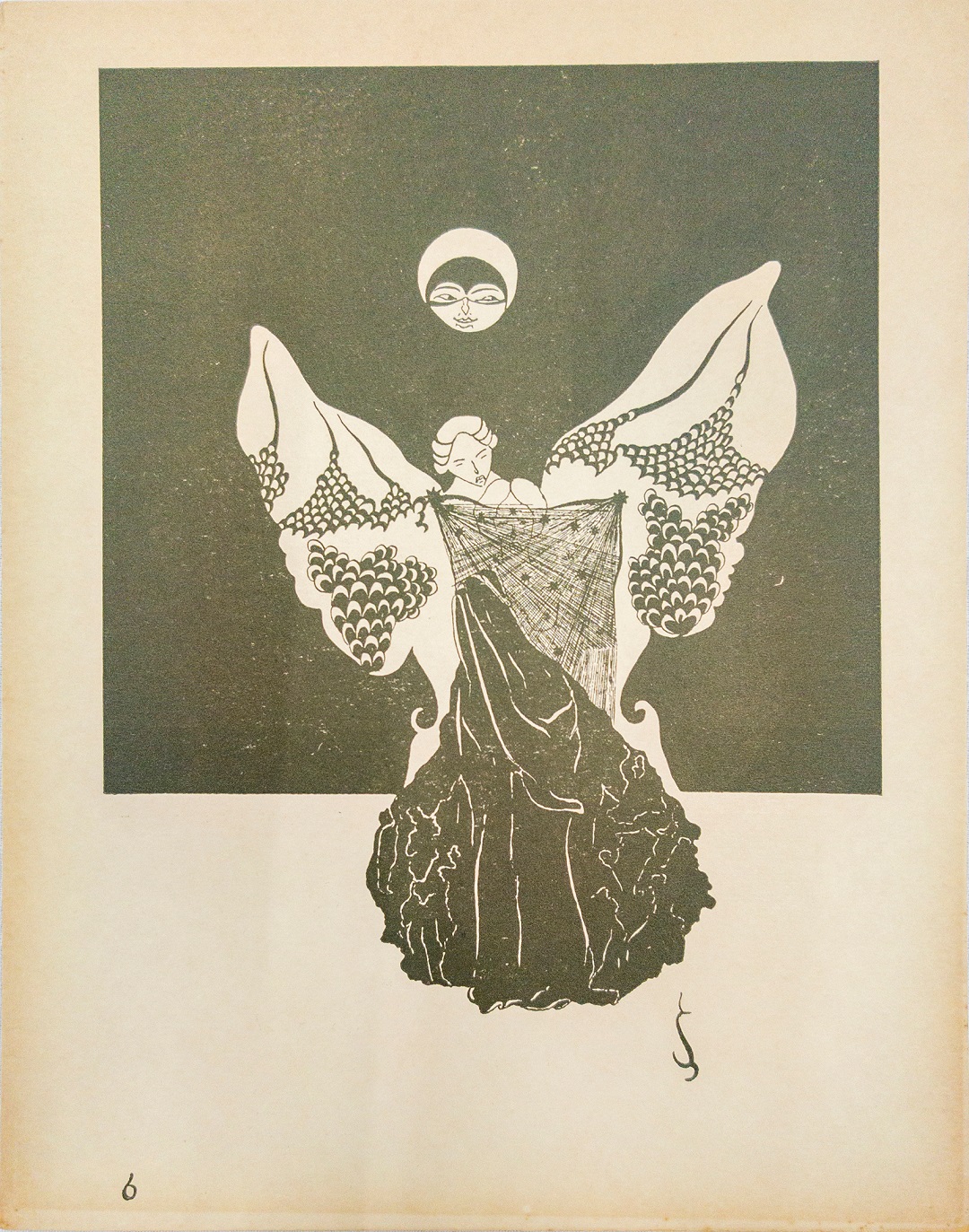

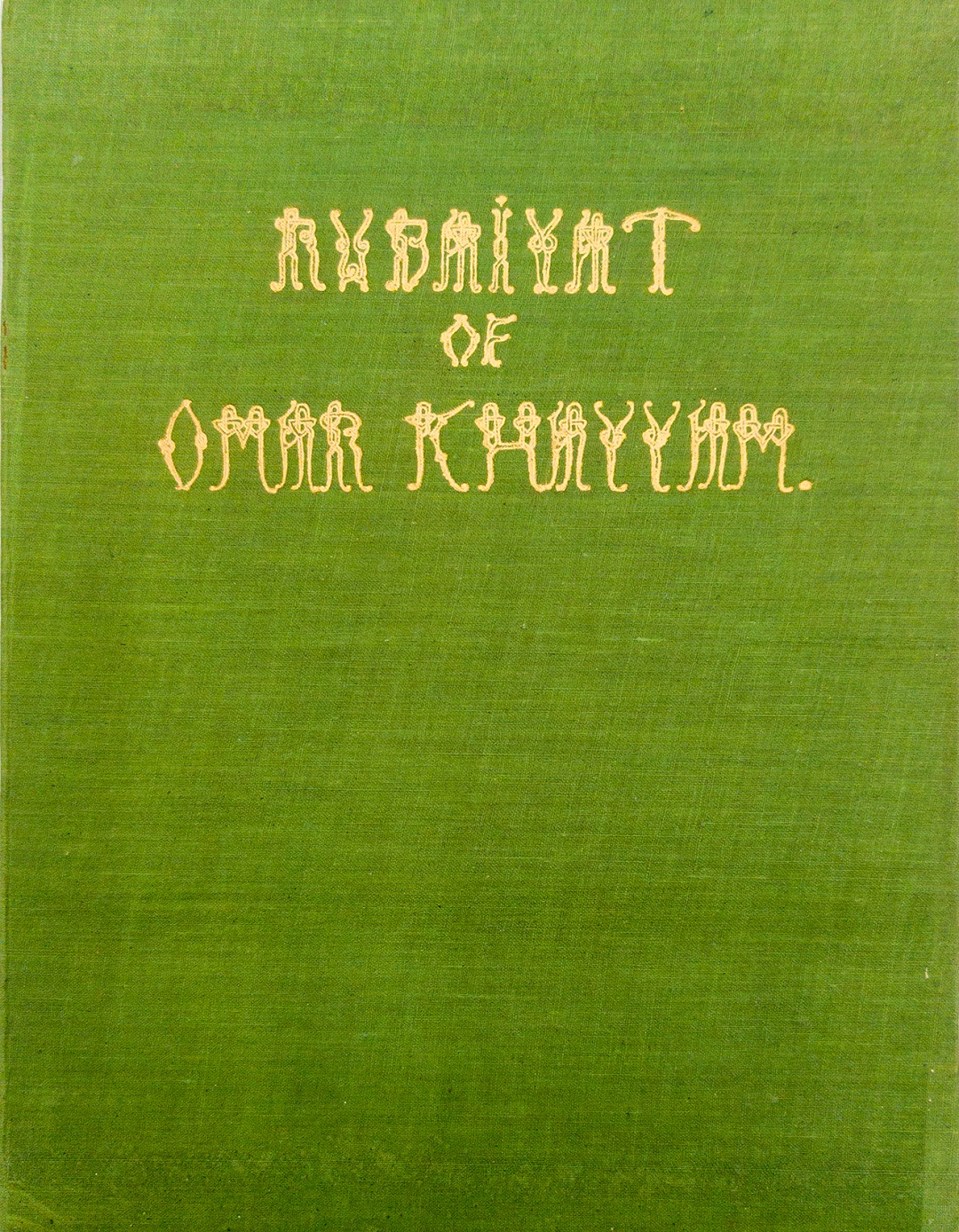

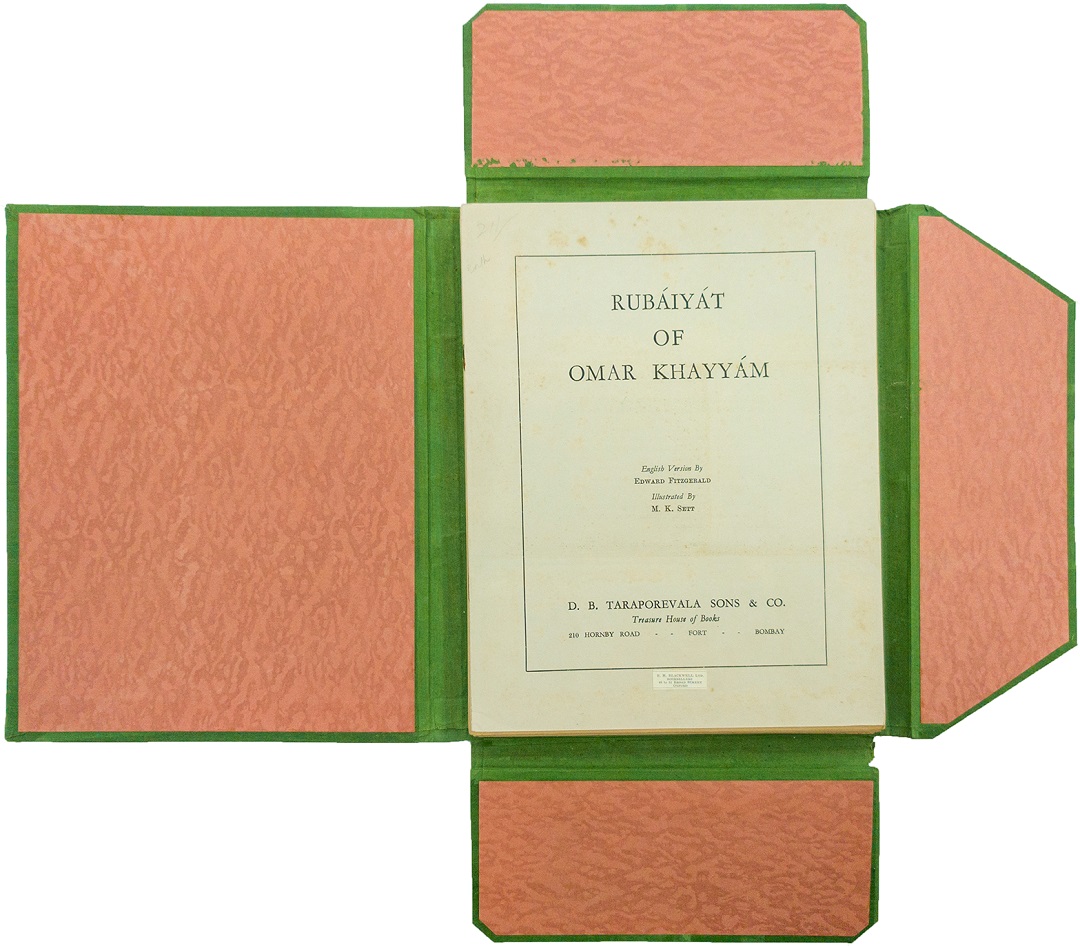

M. K. Sett

Rubaiyat of Omar Khayyam

c. 20th century

Print on paper, four flap hardcover

M. K. Sett

Rubaiyat of Omar Khayyam

c. 20th century

Print on paper, four flap hardcover

M. K. Sett

Rubaiyat of Omar Khayyam

c. 20th century

Print on paper, four flap hardcover

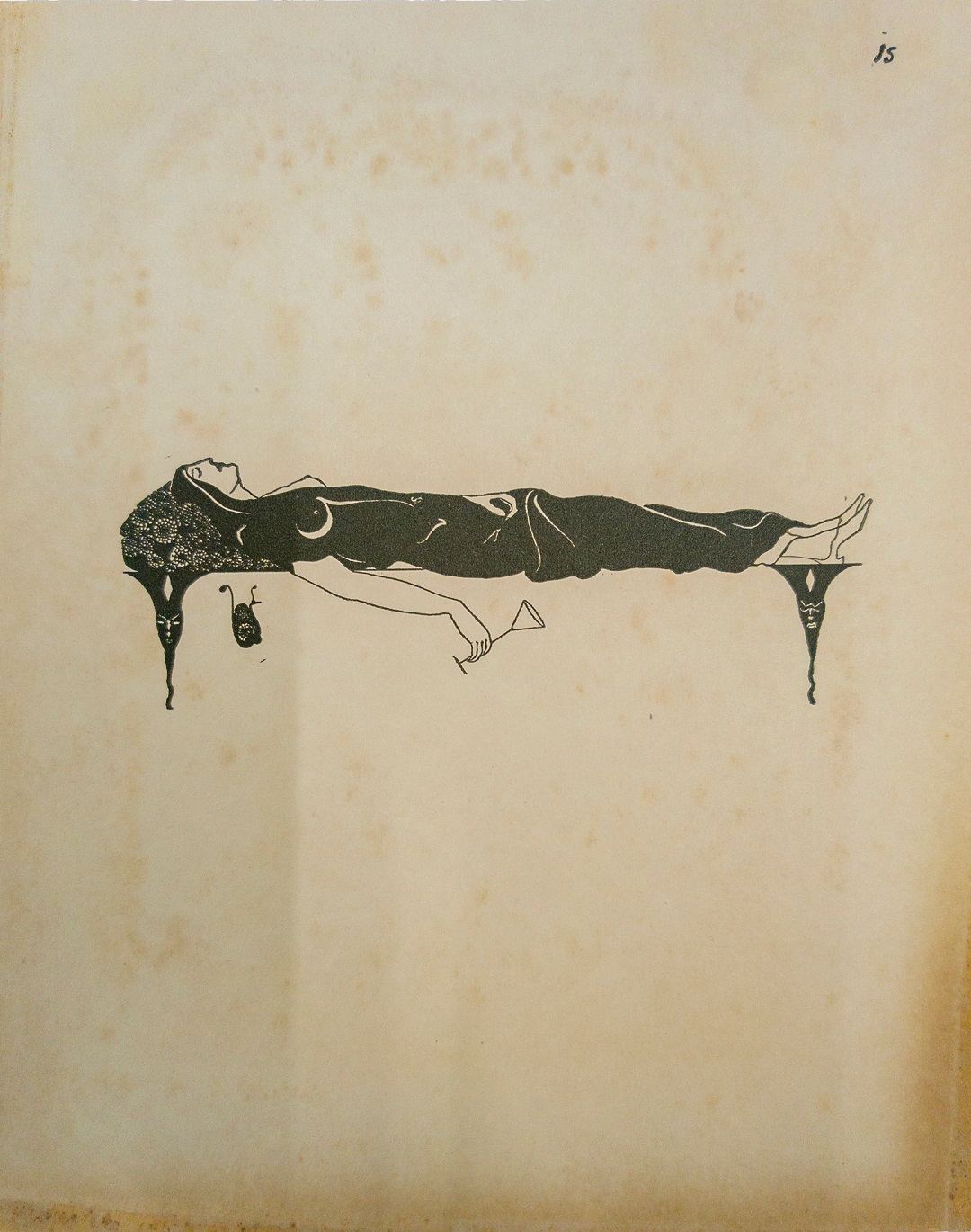

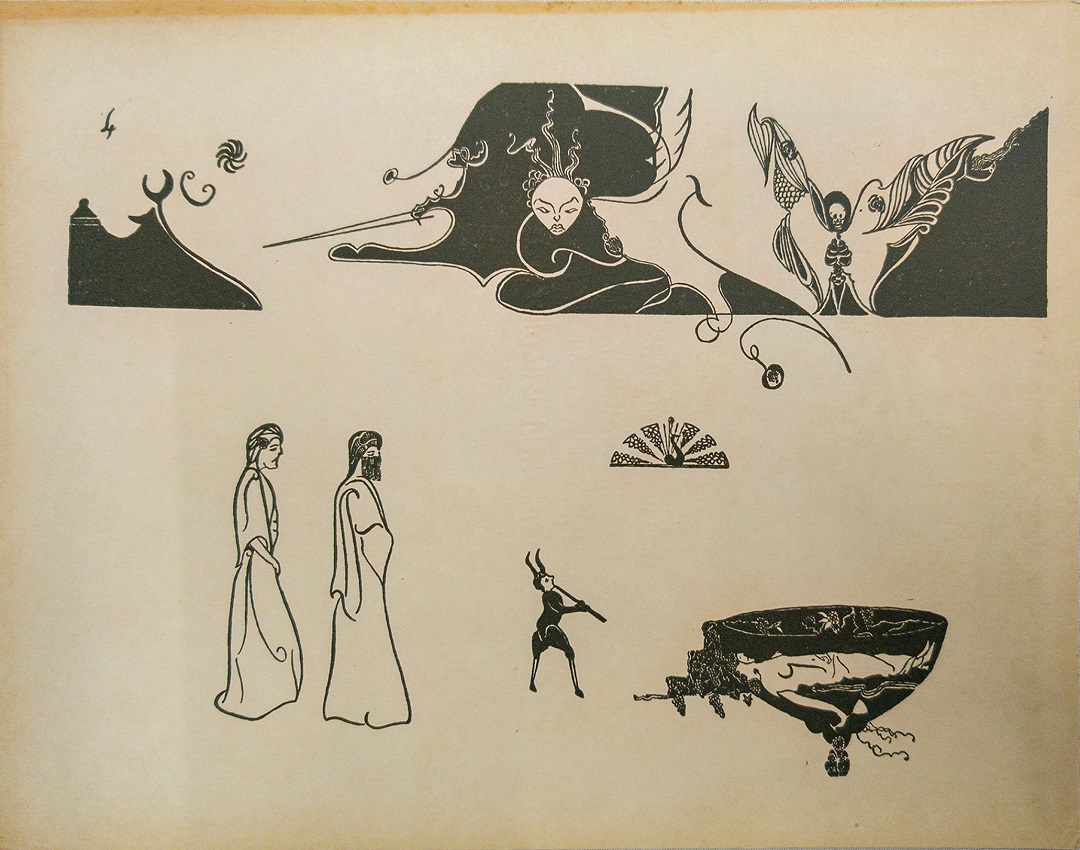

M. K. SettVery little is known of Mera Ben Kavas Sett. The first page of his Rubaiyat introduces him as an artist of great repute in Europe and as an interior decorator, but evidence is few and far in between. Originally, M. K. Sett had privately published a Rubaiyat in 1914 through Galloway & Porter at Cambridge in a limited edition of 250 copies. Sometime following World War II, a folio edition was printed by Bombay’s D. B. Taraporevala. This edition begins with a ten-page booklet containing Sett’s introduction as well as the 75 quatrains. 31 unbound cards follow the text. The first 16 cards present the same quatrains, but engraved from Sett’s own handwriting, which are printed in green with red illumination. The remaining 15 cards contain full-page monochrome illustrations, with appropriate quatrains on their verso. The visual style of these illustrations is reminiscent of Art Nouveau and Art Deco. |

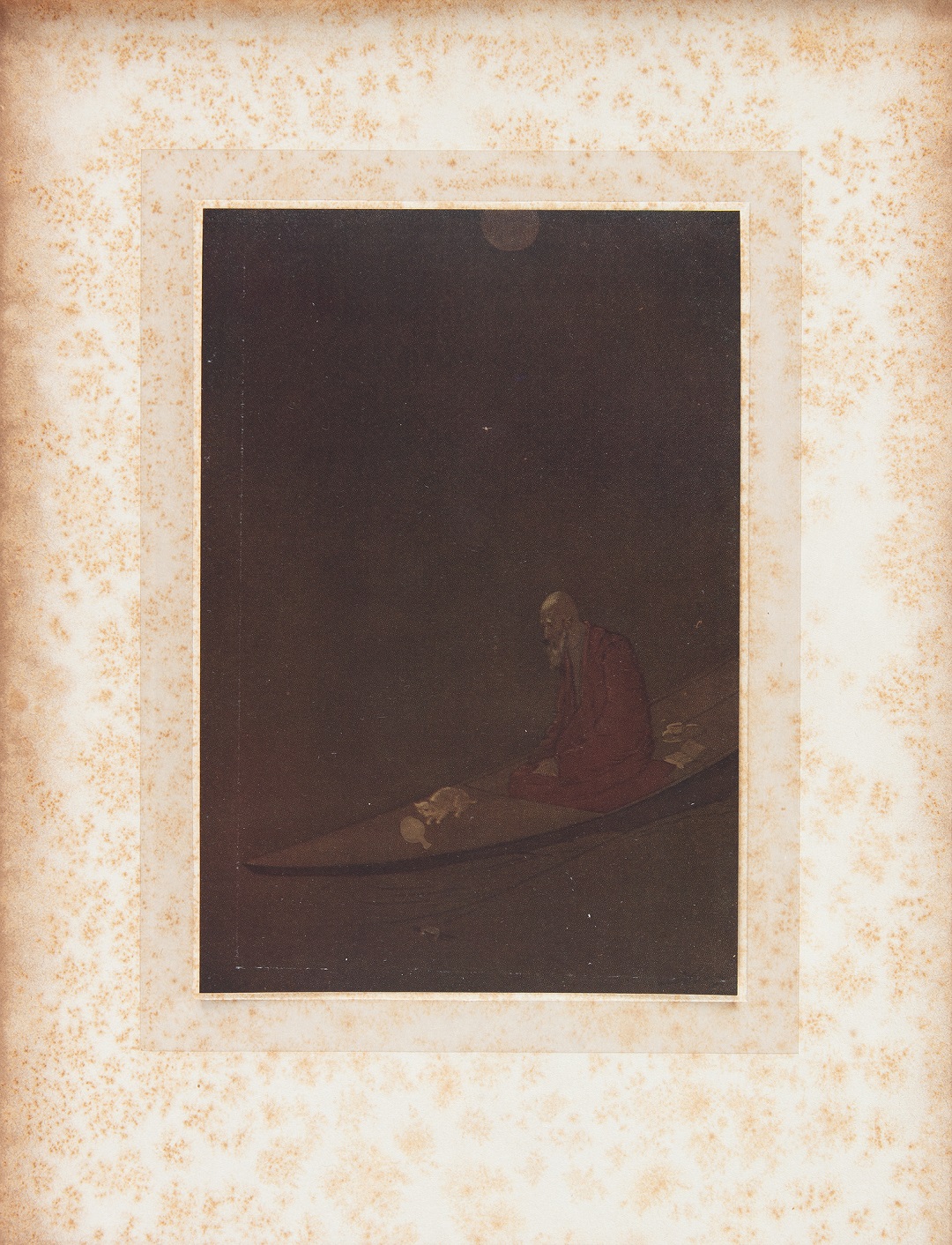

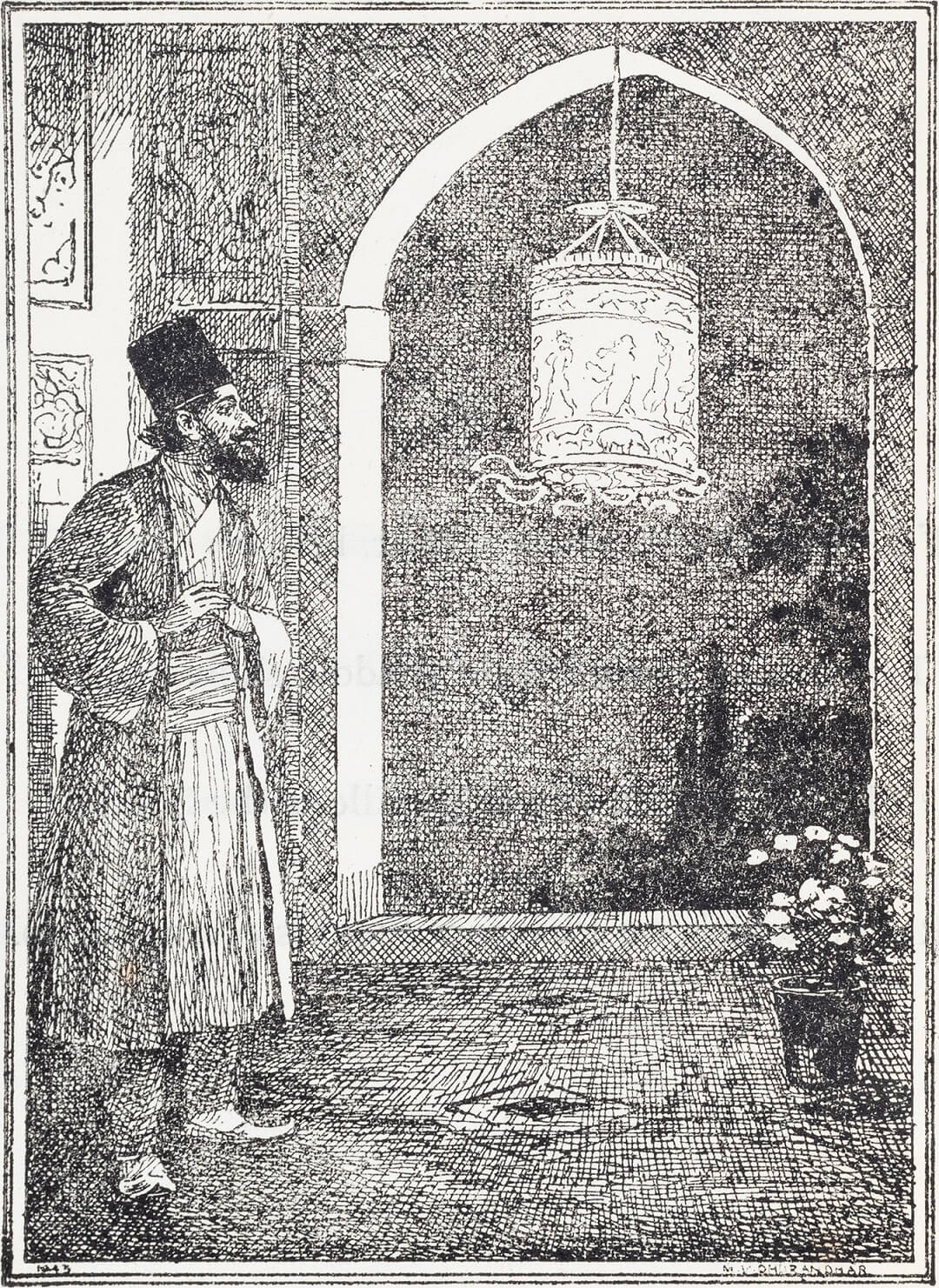

Quatrain 46

Abanindranath Tagore

Rubaiyat of Omar Khayyam

M. V. Dhurandhar

Rubaiyat of Omar Khayyam

M. K. Sett

Rubaiyat of Omar Khayyam

Quatrain 75

Abanindranath Tagore

Rubaiyat of Omar Khayyam

M. V. Dhurandhar

Rubaiyat of Omar Khayyam

M. K. Sett

Rubaiyat of Omar Khayyam

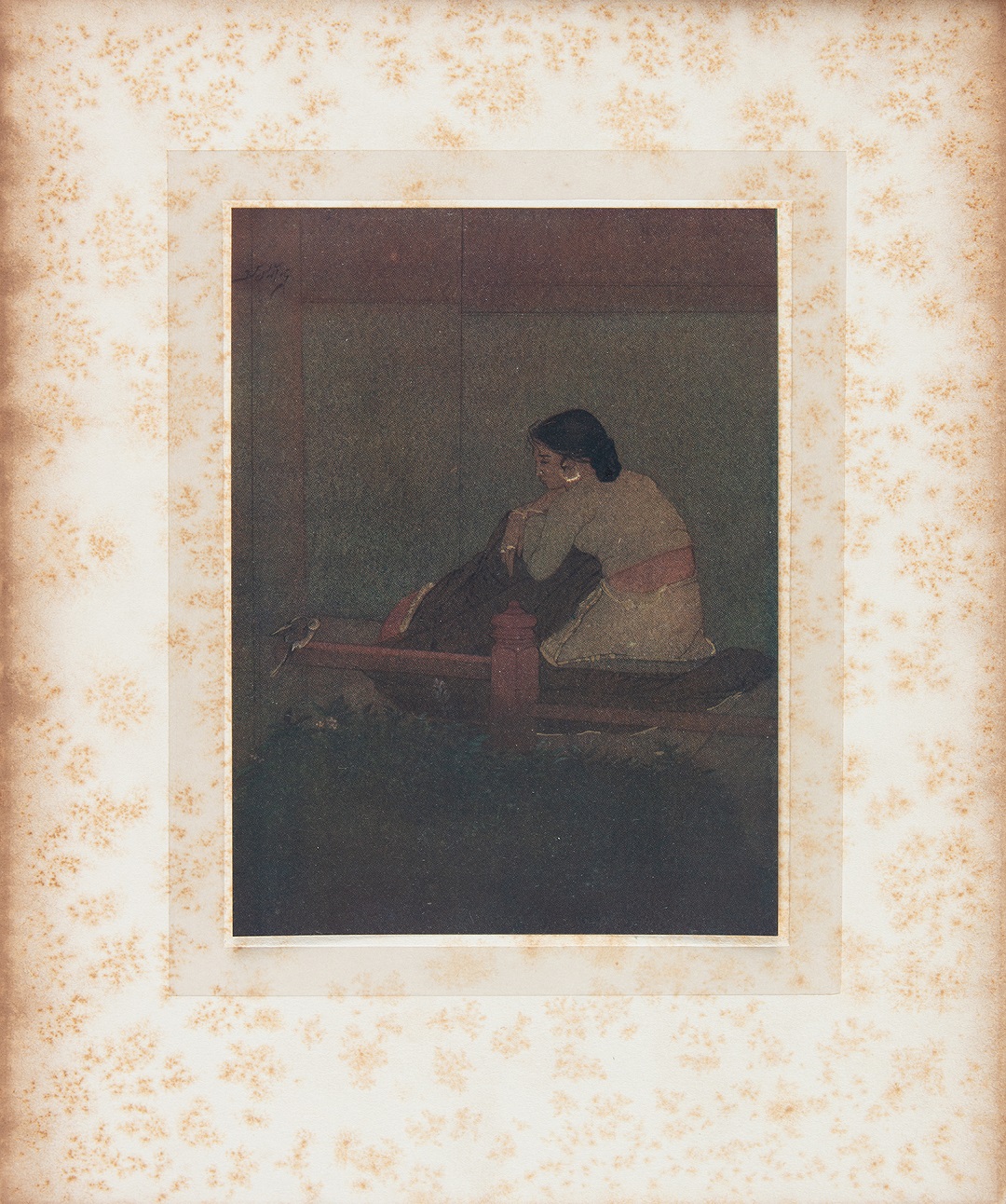

Abanindranath Tagore

Rubaiyat of Omar Khayyam

1910

Print on paper, hardcover four flap folder cover with a linen lining on the spine and glassine dust wrappers

Tagore’s Illustrations of the RubaiTagore was able to evoke the philosophical meaning of the verses. His full-colour plates show solitary figures lost in thought at dusk or night. When couples are present, they do not speak among themselves. The wash technique that he used caused colours to diffuse within the finished painting, a style that complemented the ethereal nature of the rubai. |

M. V. Dhurandhar

Rubaiyat of Omar Khayyam

1944

Print on paper, paperback

Dhurandhar’s Illustrations of the RubaiIn Dhurandhar’s drawings, the narrative of the verses is objectively represented, even though Omar Khayyam’s rubai were greatly metaphorical. Tagore and Dhurandhar take different approaches in illustrating the 46th rubai: while the shadow in Tagore’s illustration is cast by the poet sitting beside the light, in Dhurandhar the poet is presented watching a hanging lantern. His image for the 75th rubai presents a woman pouring wine from a cup, but for Khayyam ‘wine’ referred to the Spirit and the winecup the vessel for spiritual guidance. |

|

Sett’s Illustrations of the Rubai Antiquarians have compared Sett’s images to English illustrator Aubrey Beardsley. The imagery is both fantastical and abstract, with figures presented in minimally detailed backdrops. Figures are shown in the nude, wearing sunglasses or even traditional clothing such as the Parsi gara saree. In Sett’s drawings, humans share frames with hybrid mythical creatures such as nymphs and satyrs. The illustrations bear similarity with contemporary graphic novels, as drawings and text are interspersed within rectangular borders. Of the three images of the 75th rubai, Sett’s illustration makes the most profound allusion to death, because it shows a woman lying on a bed, with a wine-glass loosely placed on her hand. |

|

M.K. Sett Rubaiyat of Omar Khayyam Print on paper, hardcover four flap cover c.20th century |

Abanindranath Tagore

Rubaiyat of Omar Khayyam

1910

Print on paper, hardcover four flap folder cover with a linen lining on the spine and glassine dust wrappers

Abanindranath Tagore

Rubaiyat of Omar Khayyam

1910

Print on paper, hardcover four flap folder cover with a linen lining on the spine and glassine dust wrappers

M. V. Dhurandhar

Rubaiyat of Omar Khayyam

1944

Print on paper, paperback

M. V. Dhurandhar

Rubaiyat of Omar Khayyam

1944

Print on paper, paperback

M. K. Sett

Rubaiyat of Omar Khayyam

Print on paper, four flap hardcover

M. K. Sett

Rubaiyat of Omar Khayyam

Print on paper, four flap hardcover

The edition with Tagore’s drawing was published as a collector’s folio edition, and therefore utilised full-colour plates, gold foil and a combination of different papers. The images (measuring 7.5 x 5.2 in. each) were printed on glossy paper and mounted on thick cardstock (measuring 12.5 x 9.5 in.). Sett had privately published his first edition. The reprint was made into a folio, which used dichromatic red and green colours, followed by monochrome black ink illustrations. The pages are relatively the same size as the Tagore edition, and measure 11.0 x 8.7 in. each. Unlike the Tagore and Sett versions, Dhurandhar’s paperback copy was cheaper at the time of publication and therefore meant to have a wider distribution. At 7.2 x 5.0 in. (closed size), it was also much smaller in size than the others. Given the differences in the materials and printing technology used, what kind of audience do you think each publication catered to? |

|

From a post-colonial perspective, the FitzGerald's Rubaiyat offers multiple readings. The English poems can be studied as an example of cultural appropriation, or the stereotypical ‘othering’ of the non-Western world. The verses refer to a cup-bearer who was a young man in the Persian rubai, but changed to a young woman by FitzGerald, so a critical reading in gender studies is also applicable. When seeing the three illustrators at work, different conversations come to the forefront. Tagore constructed his technique out of Mughal miniature and Japanese painting, deliberately moving away from European conventions, echoing the sentiments of the Swadeshi movement. In Dhurandhar, we see the colonial Indian artist’s mastery over academic realism—elevating himself, and then finding success in the standard of excellence established by the colonial rule. Sett’s work is emblematic of the Art Deco movement that was taking over twentieth century Bombay, and was witnessed especially in architecture, interior design, and popularised by European artists such as Stefan Norblin. |

|

|

Looking Back at the Rubaiyat NowIn a letter addressed to Cowell, FitzGerald had stated, ‘It is better to be orientally obscure than Europeanly clear.’ Through him, we can see a larger problem that plagued Western viewership of non-Western culture: a gaze that romanticised non-Western nations as having antiquated perceptions of science and logical thinking, but celebrated their supposedly ‘mystical’ belief-systems. Since the time of the text’s first publication, have changes occurred in the way we perceive different cultures? |

However, FitzGerald’s Rubaiyat is undoubtedly charming. The verses act as timeless adages that invoke in the reader the spirit of carpe diem. In specific instances, quatrains show the ability to transcend cultures and Orientalist politics. An example is verse 37, from the first edition: Ah, fill the cup: what boots it to repeat |

further reading

More about Abanindranath Tagore in '150 Years of Abanindranath Tagore'.

Bob Forest, Appendix 17: Mera K. Sett & Rupert Brooke, The Rubaiyat of Omar Khayyam Archive. Read More

Manan Kapoor, 'Why Edward FitzGerald's Rubáiyát of Omar Khayyam is one of the most controversial translations ever', Scroll, 22 June 2019. Read More

Dick Sullivan, 'Edward FitzGerald's The Rubaiyat of Omar Khayyam', The Victorian Web, 17 January 2014. Read More

Edward FitzGerald, Edward Henry Whinfield, and J. B. Nicolas, The Sufistic Quartrains of Omar Khayyam (New York & London: M. Walter Dunne, 1903). Read More

Bob Forest, 'Kuza-Nama,' Verse by Verse Notes on The Rubaiyat (1859 edition), The Rubaiyat of Omar Khayyam Archive. Read More

'Tanam Shud case', Wikipedia. Read More

Credits

Written by Shatadeep Maitra

Archival material curated by Sanjana S.