The School and the City: The J. J. School of Art in BombayThe Editorial Team July 01, 2024 The Sir Jamsetjee Jejeebhoy School of Art, commonly known as the J. J. School of Art, is one of the oldest and most well-known art institutions in India. Established in 1857 through a donation by the Parsi businessman Jamsetjee Jejeebhoy, the school was initially set up at the Elphinstone College premises and offered elementary drawing and design classes, moving eventually to the present building in 1878. How did the school participate in the construction of the city that surrounded it? Some of its most prominent landmarks, especially those going back to the nineteenth century, were created under its influence, making the growth of the city and the school mutual constitutive. Let’s take a brief look at this evolving history of the school and its significant contributions to the cityscape. |

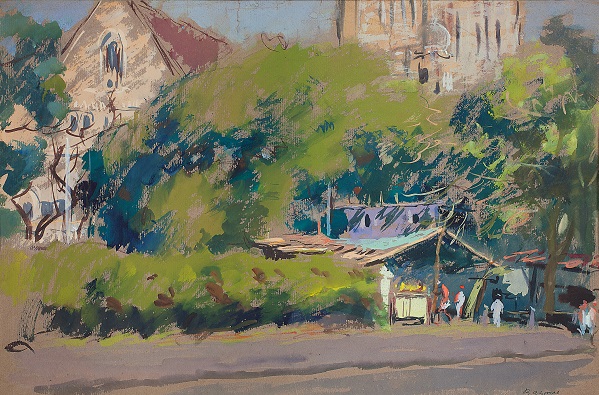

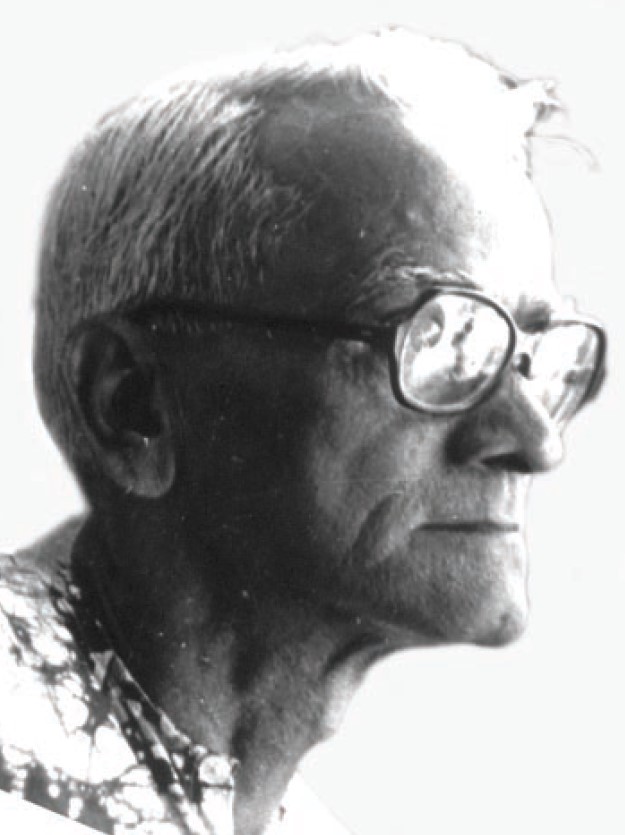

Baburao Sadwelkar

Tea House Across J.J.

1951, Watercolour on paper, 14.3 X 20.8 in.

Collection: DAG

|

Sir Jejeebhoy was inspired by the Great Exhibition of London in 1851, and his trips to various countries like China where he admired the variety of crafted objects. Besides a generous endowment, he wrote a letter to the Governor Lord Falkland on 9 May, 1853, proposing the ‘establishment of a school for the improvement of arts and manufacture… (which would enable the) employment of the people and the general improvement of the habits of the industry of the middle and lower classes of our native population.’ |

|

|

George Chinnery

Sir Jamsetjee Jeejebhoy and his Chinese secretary

Image courtesy: Wikimedia Commons

In 1865, the school appointed British painter James Payton and two other teachers, Joseph Crowe and Geroge Wilkins Terry, who ‘offered training in European art and aesthetics.’ Crowe, a scholar of the Renaissance, ‘taught orthographic projection, geometry and figure drawing to students’ with an emphasis on ‘training students to copy from works of classical artists so that they could acquire technical skills to render drawings from life later.’ These skills of draughtsmanship would also enable the graduates to secure jobs with the colonial administration as surveyors and documenters of territory and landscape around the country. |

|

Baburao Sadwelkar on the early years of J. J.: ‘In the J. J. School of Art training in drawing, painting and design was launched along the system followed by art schools in England. Drawing of Greek and Roman antiques in light and shade was introduced and human models were engaged for the study of portraiture. Lessons of rendering tonal values in monochrome and in colour were accepted and mastered by the students. The skill and perception of these artists is evident in their work. The theory of linear and aerial perspective was altogether new to the students. Before long the students began to feel that their traditional way of painting lacked any theoretical or scientific base. The British, along with running art schools, also undertook several archival projects. One of them was of copying the Ajanta frescoes and the work was assigned to the J. J. School of Art.’ |

|

|

John Lockwood Kipling

John Griffiths

1865

Image courtesy: Wikimedia Commons

John Griffiths and students from the Bombay School of Art

Copy of painting inside the caves of Ajanta (Cave 2)

1881-83, Oil Painting

Image courtesy: Wikimedia Commons

In 1865, the school brought on John Lockwood Kipling and John Griffiths from the South Kensington School of Art in London, marking a shift towards ‘a focus on decorative and industrial arts.’ Under their leadership, ‘architectural design came to be offered and the school became involved in urban planning’. As Sadwelkar noted, copying the frescoes of Ajanta was a major undertaking under the auspices of Griffiths, which would eventually percolate into the styles of Indian modern artists. Sadwelkar writes, ‘Griffiths observed that one of “the most curious and interesting of my experiences was the initiation of Hindu, Farsi and Goanese students in the mysteries of an art still congenial to the oriental temperament and hand—I am persuaded that no European, no matter how skillful, could have so completely caught the spirit of the originals.” However, none of the artists of that period were drawn to the aesthetics of Ajanta, but aspired to master the Western technique of illusionistic realism.’ Thus, the construction of the Ajanta copies as a source for rejuvenating modern Indian art was a slow process, initially resisted by the students themselves, until it became a norm for formulating a classical basis for Indian modern art. |

|

From 1900 onwards, architecture became an important discipline in the school’s roster. The students were involved in decorating landmark buildings in Mumbai, including the Victoria Terminus Station (now Chhatrapati Shivaji Terminus), Crawford Market (now Mahatma Jyotiba Phule Mandai), and Rajabai Towers. Even today, a flyover outside the School is colloquially known as ‘the JJ flyover’. |

|

|

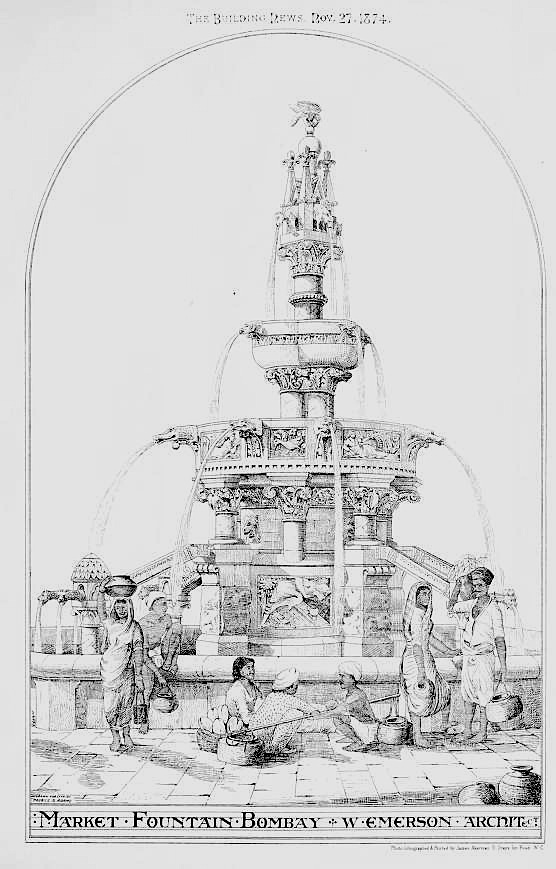

William Emerson

The Crawford Market Fountain

Image courtesy: Victorianweb and Wikimedia Commons

Detail of Crawford Market frieze

Photographer: Ramachandran Venkatesh, courtesy: Victorianweb

Although William Emerson was the chief architect for the Crawford Market (the old name is still commonly used), built in 1869 and donated to the city by Cowasji Jehangir, students from the J. J. School, led especially by Principal John Lockwood Kipling, were instrumental in creating the decorative features of the market that expresses a blend of classical, western sculpture and Indian subjects. Designs and copies of the features and the structure were exhibited back in London too, highlighting the exchanges between colonial styles and indigenous works that were being produced at the time. Writing in the 1980s, Jan Morris suggested that these ‘friezes’ represented ‘ideal market-people and their clients, women with plump babies, well-built porters with luscious loads ... presenting a paradigm of what a market ought to look like, in the dreams alike of the imperial British and the arts and crafts movement...’ |

Baburao Sadwelkar

Hornby Road Leading to Crawford Market Adorned with Vermilion Trams

1951, Watercolour on paper, 15.0 X 22.0 in.

Collection: DAG

Carwford Market (detail)

Photographer: Ramachandran Venkatesh, courtesy: Victorianweb

She further observed that, ‘Fruits, fish, meats, poultry and various craftwork were all sold in it, and it looks today, in its functions as in its substance, almost exactly as it did when it was built. Inside it is unexpectedly fine. A central hall with two wings, Moorishly arched, it is lined with wooden stalls, often set on several tiers, so that market-people are to be seen high above their produce, bawling offers or reaching down for cash. The floor is clad in flagstones from Caithness, there are ecclesiastical windows at each end, and the whole structure is fitted out, wherever you look, with whimsical iron lamp-brackets in the shape of winged dragons—perched upon by pigeons, and fouled by their immemorial droppings, but still graceful and surprising.’ |

|

In 1890, the school ‘was taken under the auspices of the Education Department of the Government of Bombay’ and ‘regular examinations were introduced, following the example of South Kensington.’ By 1891, the school had five distinct departments: ‘Drawing and Painting, Sculpture and Modelling, Architecture, Applied Arts and Arts and Crafts.’ These workshops were founded under the governorship of Lord Reay, who served as the Governor of Bombay from 1885 to 1890, and were therefore named The Lord Reay Art Workshops. They were housed in the Sir George Clarke Studies and Laboratories building, which was constructed specifically for this purpose. During the early 1890s, the Lord Reay Art Workshops were very active, with the sound of craftsmen's mallets ringing through the workshops and the spaces glowing with their work. |

|

|

Victoria Terminus (C. S. T.)

Photographer: Ramachandran Venkatesh, courtesy: Victorianweb

Victoria Terminus (C. S. T.)

Photographer: Ramachandran Venkatesh, courtesy: Victorianweb

The Victoria Terminus (now known as Chhatrapati Shivaji Maharaj Terminus or CSMT) in Bombay (Mumbai) is an iconic railway station known for its Victorian Gothic architecture. It was designed in the High Victorian Gothic style by British architect Frederick William Stevens. Students and craftsmen from the J. J School of Art were involved in creating the ornamental and decorative elements of the Victoria Terminus. This included intricate carvings, sculptures, and other artistic embellishments that adorn the building's facade and interior. This style was characterised by its pointed arches, intricate carvings, spires, and stained-glass windows, possibly designed by students trained at the stained-glass workshops at the School, reflecting a blend of Victorian and Indian architectural influences. The construction of the Victoria Terminus began in 1878 and was completed in 1887. It took almost a decade to build this grand structure, which stands as a symbol of Mumbai's Victorian-era architectural prowess. The building is constructed primarily of a combination of stone, including coarse-grained Kurla basalt for the walls and fine Porbandar sandstone for decorative elements. These materials were locally sourced and contributed to the building's durability and aesthetic appeal. |

Victoria Terminus in 1870 with the statue in the canopy below the clock

Image courtesy: Wikimedia Commons

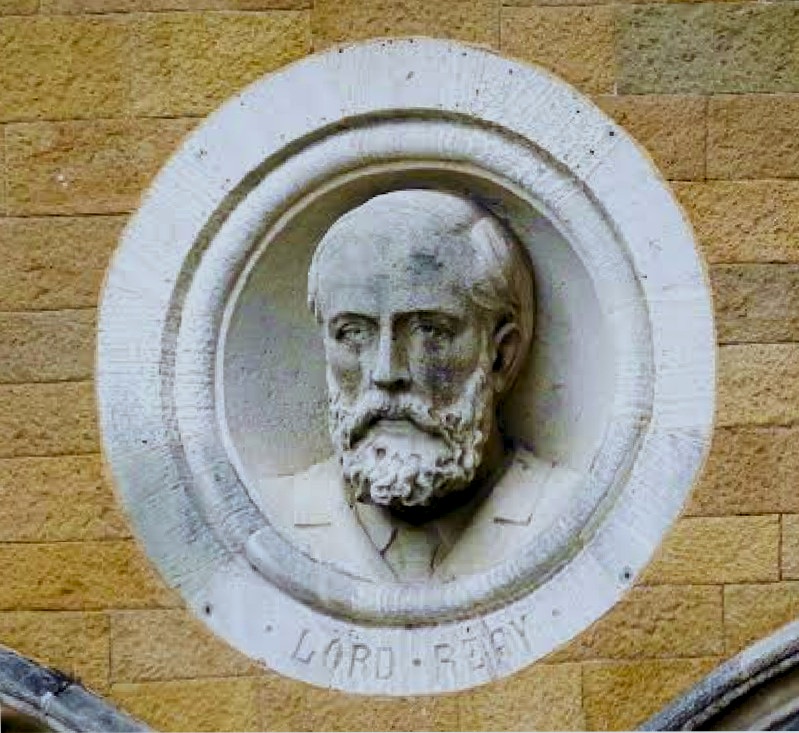

Medallion depicting Lord Reay, designed by Thomas Earp, at the Victoria Terminus (C. S. T.)

Image courtesy: Victorianweb

One of the most striking features is its high central dome, which rises above the main entrance. The dome is adorned with intricate carvings and topped with a crowning figure of a woman holding a torch, symbolizing progress. The station is flanked by turrets and towers, each intricately detailed with carvings and sculptures that depict various motifs including animals, flowers, and Indian architectural elements. The interior features stunning stained-glass windows that depict scenes from Indian mythology and British history, adding a colorful and majestic aura to the station. Beyond its architectural splendor, the Victoria Terminus was designed to be highly functional, accommodating the burgeoning railway traffic in Bombay. It served as a major hub connecting different parts of India through its extensive railway network. Those responsible for the bringing in of the railways, either Directors of the Great Indian Peninsula Railway or other prominent people of that age, such as Sir Jamsetjee Jeejeebhoy, Lord Reay, Jagannath Shankarshet and others, are honoured on the walls with busts in a series of medallions. |

|

Through an evolving set of pedagogical changes, a process through which innovative teachers worked with gifted students, a thorough grounding in craft and knowledge of art, the school became a hub of technical arts education soon, and eventually, a great center for fine arts practitioners in India. Since the late 1930s and 40s, through the effort of figures like Shankar Palshikar and others, the school would produce some of the most significant artists and architects of modern India, who would reshape the landscape of art for a postcolonial nation. The school’s glittering set of alumni includes M.V. Dhurandhar, M.F. Husain, Akbar Padamsee, F.N. Souza, Tyeb Mehta, S.H. Raza, Homai Vyarawalla, Bhanu Athaiya, B.V. Doshi, K.K. Hebbar, K.H. Ara, Uday Shankar, Prabhakar Barwe, Atul Dodiya and Tushar Joag. In 1952, the Department of Architecture became a part of the University of Mumbai, and the Sir JJ School of Architecture was established. In 1961, the Applied Arts department branched out and was recognised as an independent institute under the University of Mumbai. In 1981, the entire school became affiliated with the University of Mumbai. |

|

|

M. V. Dhurandhar

Indira Devi

Oleograph on paper, 27.5 x 19.7 in.

Collection: DAG

Shankar Palsikar

Image courtesy: Wikimedia Commons

K. K. Hebbar

Fishing

1991, Oil on Masonite board, 21.7 x 27.2 in.

Collection: DAG

Kipling bungalow in the campus of the Sir J. J. School of Art, Mumbai

Image courtesy: Wikimedia Commons

Today, the Sir JJ School of Art offers undergraduate and graduate degrees in Painting, Sculpture, Metal Work, Ceramics, Textile Design, and Interior Decoration, along with diploma courses in Art Education and Teaching. The school's heritage building, constructed in 1878 in neo-Gothic style, is recognised by the Government of Maharashtra as a protected structure. A historian and teacher at J.J., Manisha Patil, writes, ‘Sir. J.J. School of Art has several distinguishing features a sprawling tree lined campus in the heart of Mumbai, a Grade II heritage building with well lit spacious studios, superlative skills, perhaps some of the best in the country, and a strategic location with close proximity to museums and public/private galleries. The Dean’s charming old bungalow on the campus, where the renowned writer Rudyard Kipling, whose father Lockwood Kipling was a respected teacher at J.J., spent his childhood, has also attracted a fair amount of public attention.’ |