The Printed Picture: Four Centuries of Indian Print-Making

The Printed Picture: Four Centuries of Indian Print-Making

The Printed Picture: Four Centuries of Indian Print-Making

|

The Printed Picture: Four Centuries of Indian Print-Making Jawahar Kala Kendra Jaipur, 8 Aug – 6 Oct 2017 An exhibition by DAG Annoda Prasad Bagchi Untitled (Vijaya) Handtinted chromolithograph |

|

As printing technologies improved around the turn of the 18th century, a large number of cheaply reproduced printed pictures—illustrated books, almanacs and mythological images—became available to the common people. This became an important vehicle of social change because people could own, produce and disseminate images of all kinds—from their beloved deities and favourite fictional characters to political cartoons critiquing colonial authorities. Printmaking was equally treasured by artists for its aesthetic potential, as techniques like lithography, etching, metal engraving, viscosity, gave practitioners infinite opportunities for creative exploration. This landmark exhibition gives us a comprehensive overview of the history of the printed picture in India. |

|

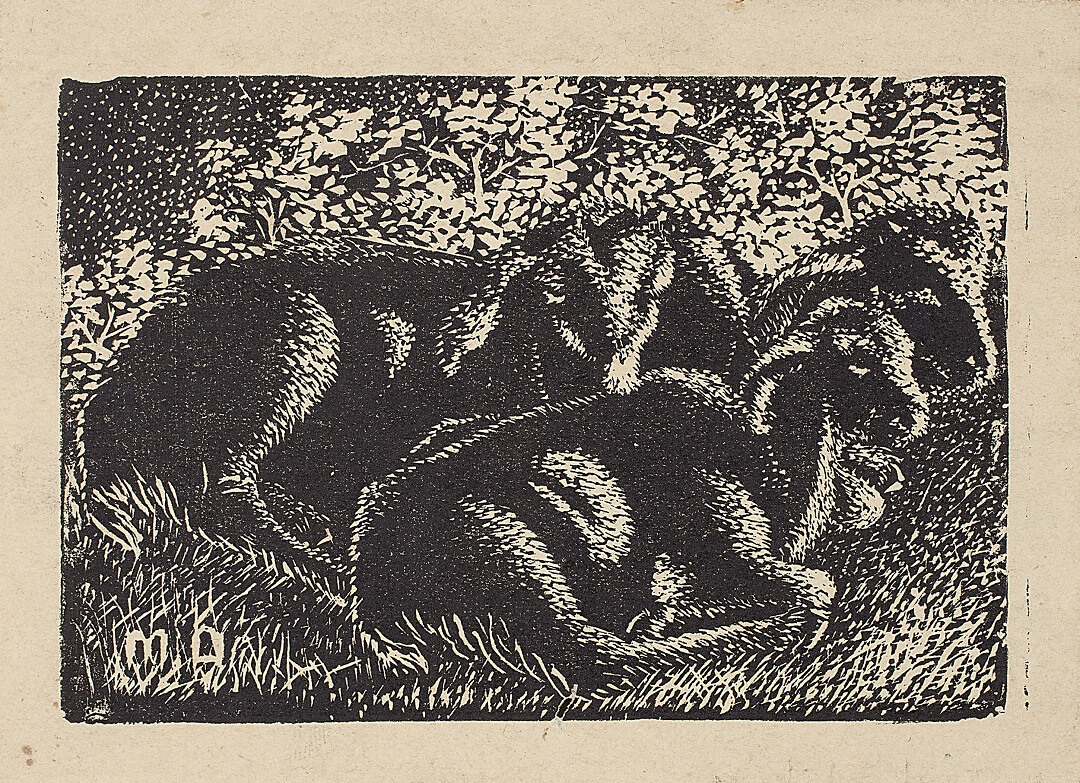

Sanat Kar Fleeting Faces Wood intaglio |

|

FROM THE DISTANT SHORES: EUROPEAN PRINTMAKERS From 1769 onward travelling European artists began arriving on the shores of India and introduced new technologies like lithography to produce prints of the landscapes they painted. These images became some of the earliest documentation of the colonies and printmaking techniques made it possible for them to circulate far and wide. As the demand for landscapes began to wane in markets abroad, landscape painters from England and Europe flooded the colonies to take advantage of the fledgling but lucrative market in printed pictures. |

|

Robert Grindlay, T. Kearney, C.F Hunt Aurangabad - From the Ruins of Aurangzeb’s Palace Handtinted etching and aquatint |

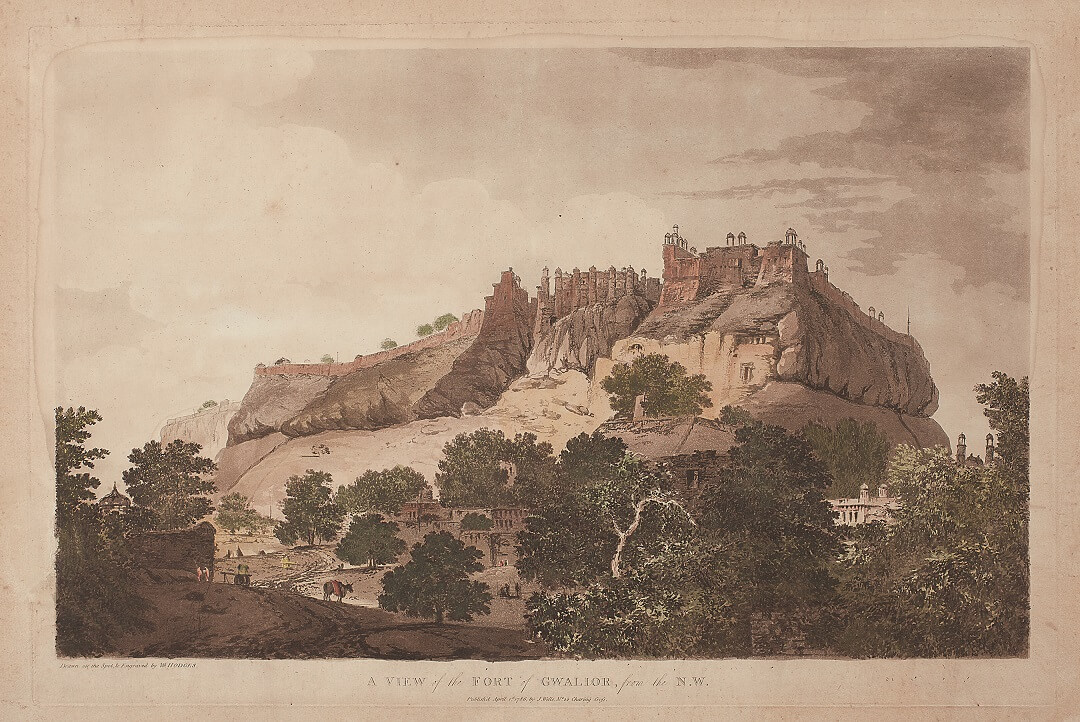

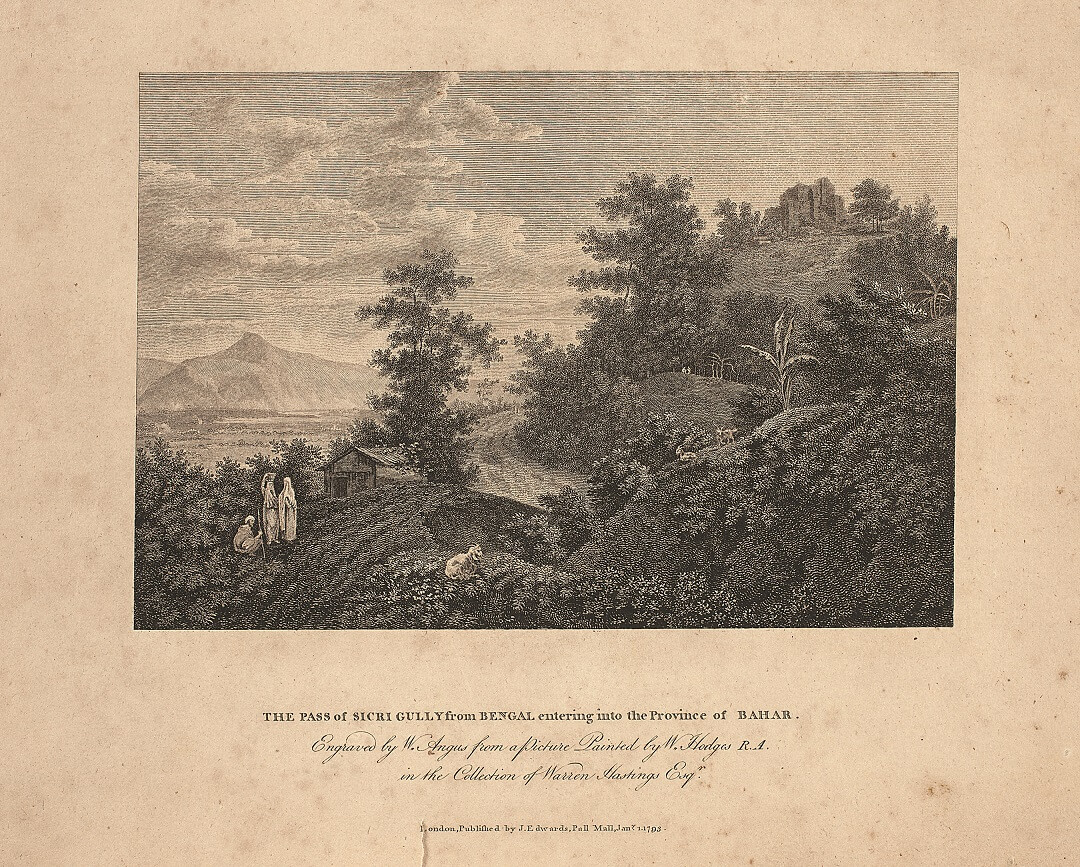

William Hodges

A View of the Fort of Gwalior, from N.W.

Handtinted etching and aquatint

William Hodges and W. Angus

The Pass of Sicri Gully from Bengal Entering into the Province of Bahar

Metal engraving

The first notable landscape artist to arrive in India was William Hodges in 1780. For the next three years he travelled the length and breadth of the country and produced a large number of sketches which he printed using techniques like metal engraving and etching. Between 1785-88 he published a series of forty-eight aquatints titled Select Views in India. Hodges’ landscapes, unlike the uncle and nephew duo Thomas and William Daniell, were less realistic in nature, carrying an air of shock and unrest created by the stark contrast of light and shade. |

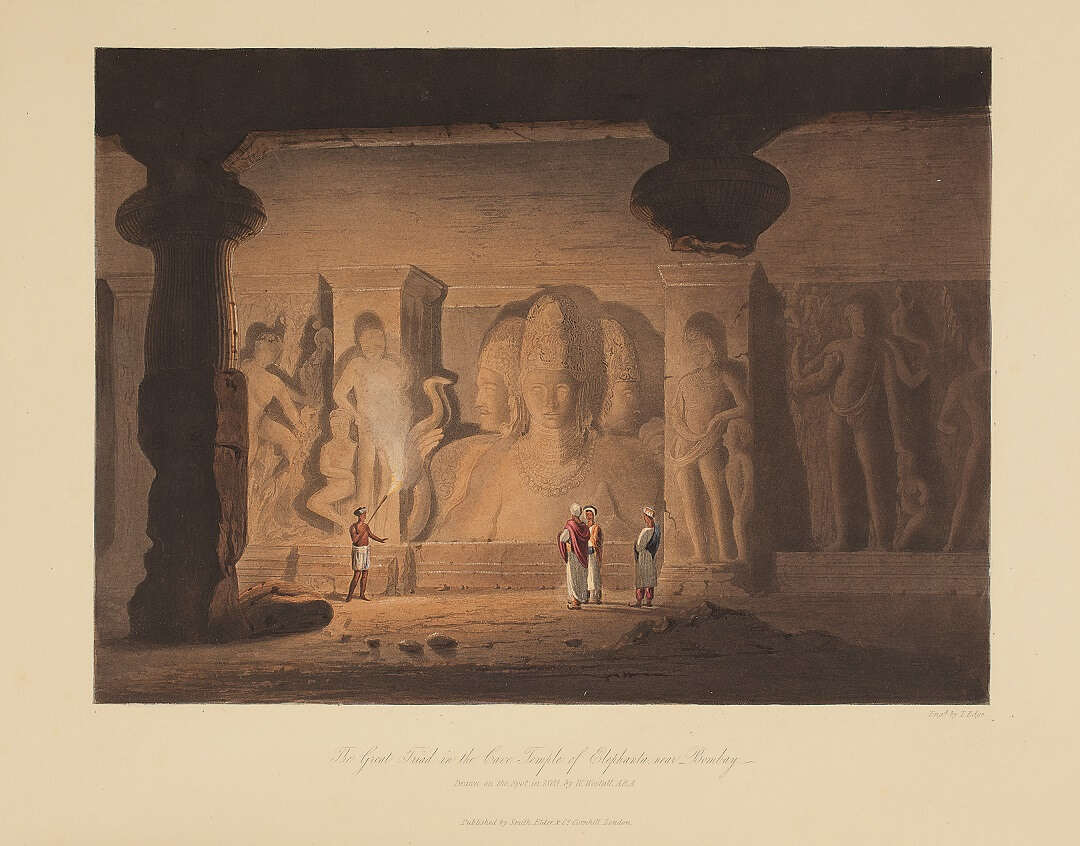

W. Westall and T. Edge

The Great Triad in the Cave Temple of Elephanta near Bombay

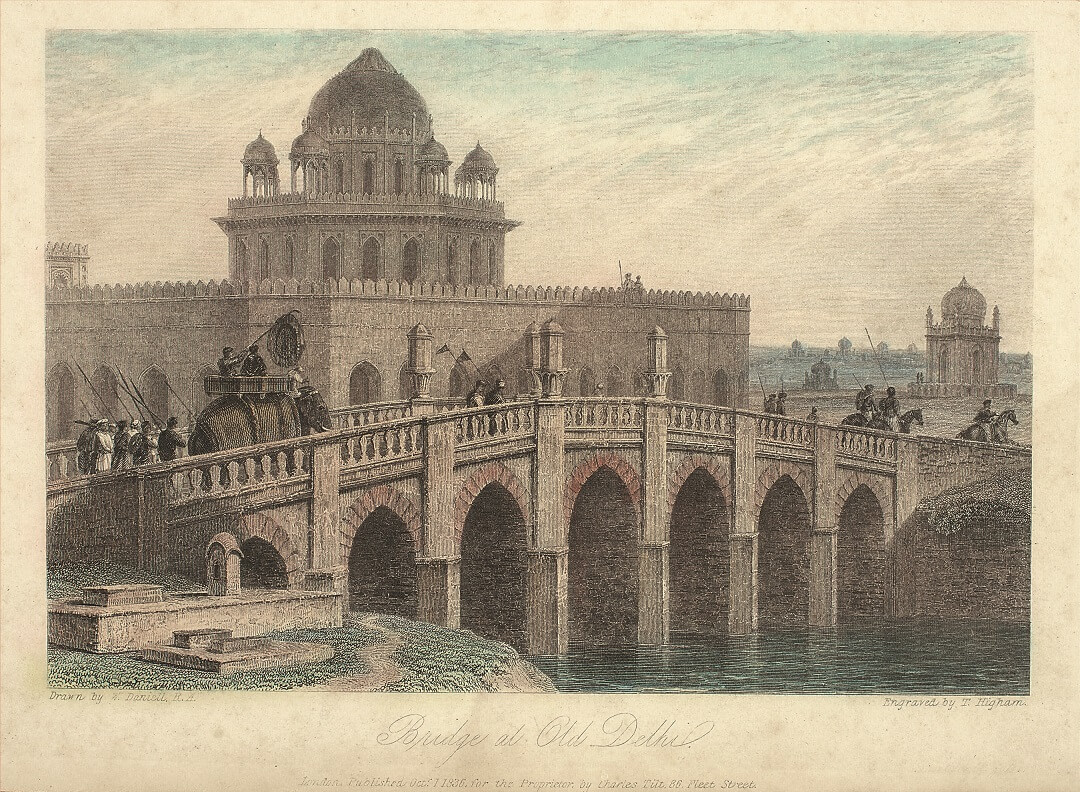

William Daniell and T. Higham

Bridge at Old Delhi

Hodges was followed by a number of artists such as James Baillie Fraser, Charles D’Oyly and the like. Among them Thomas and William Daniell’s Twelve Views of Calcutta is a significant contribution in documenting different aspects of life in the colonial city. Most of these artists used their paintings as studies for subsequent engravings, aquatints, lithographs and etchings. This resulted in the circulation of a large number of prints by the end of the 18th century. These images of landscapes and ruined monuments defined the colonial perception of India for a long time to come.

|

THE INDIGENOUS STORY: INDIAN PRINTMAKERS AND POPULAR PRINTS Indigenous printmaking developed along a different trajectory. Among the first artisans to adapt to printmaking were metalworkers like iron, gold and coppersmiths. By the mid 19th century, wood and metal engravers around north Calcutta’s Chitpur area in Calcutta had grown into a prominent community of printmakers with a steady market. They also attracted indigenous picturemakers or patuas from local pilgrimage sites like the Kalighat temple, who, in order to compete with the new pace of picture production, brought their watercolours to get them cheaply reproduced. |

|

Calcutta Art Studio Samosto Dev Devi Murti Chromolithograph |

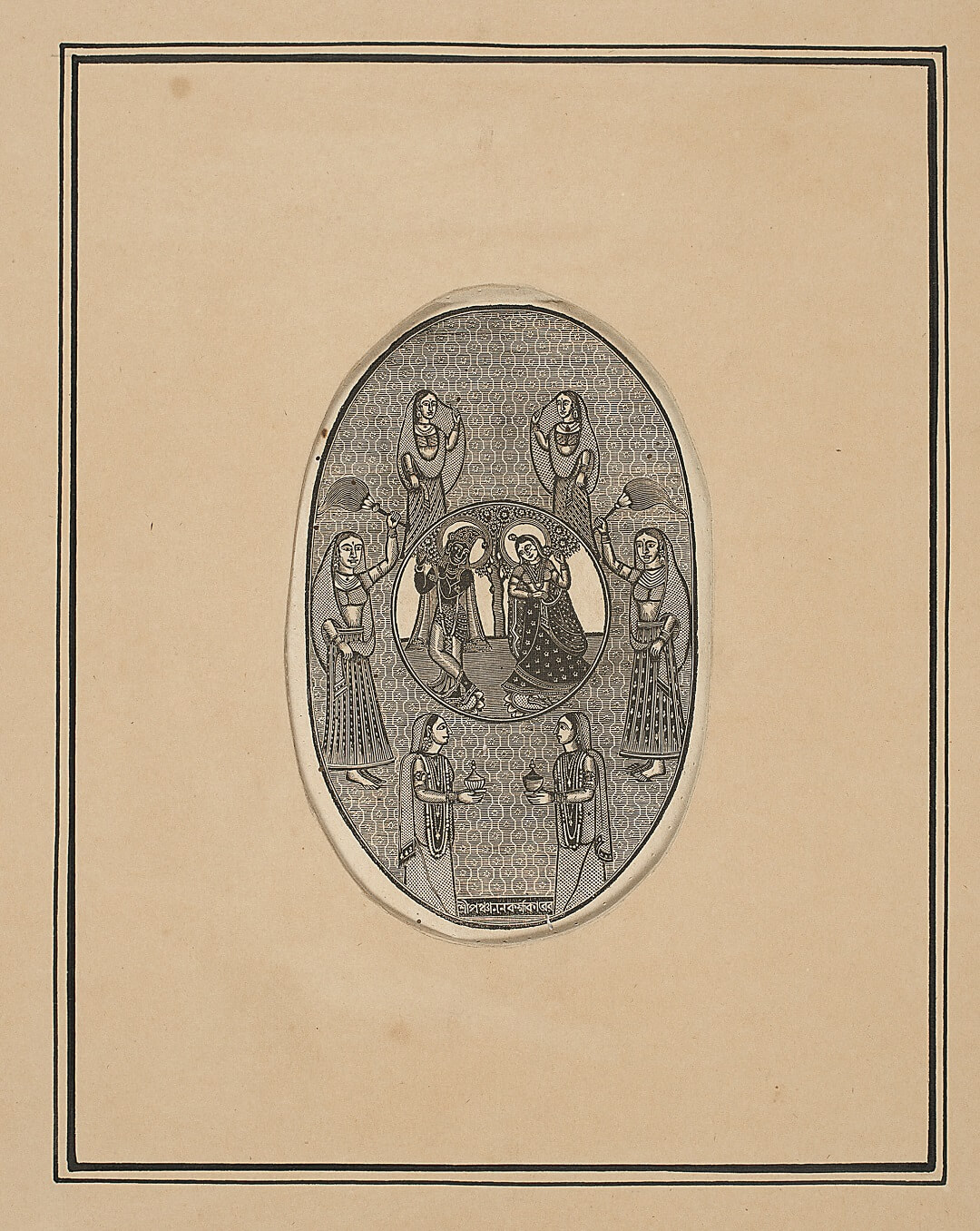

Panchanan Karmakar

Untitled (Radha and Krishna)

Wood engraving

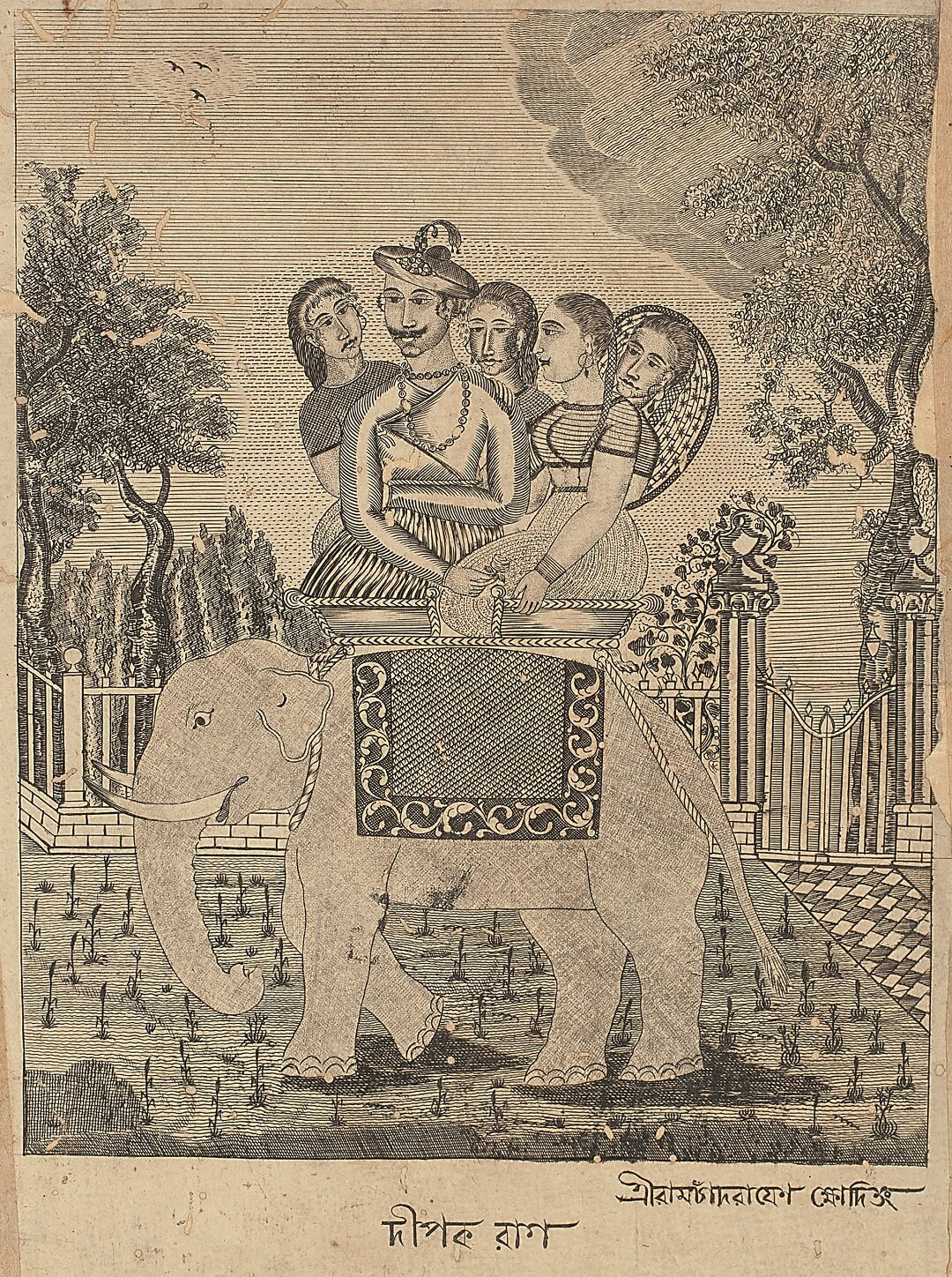

Ramchaund Roy

Deepak Raag

Metal engraving

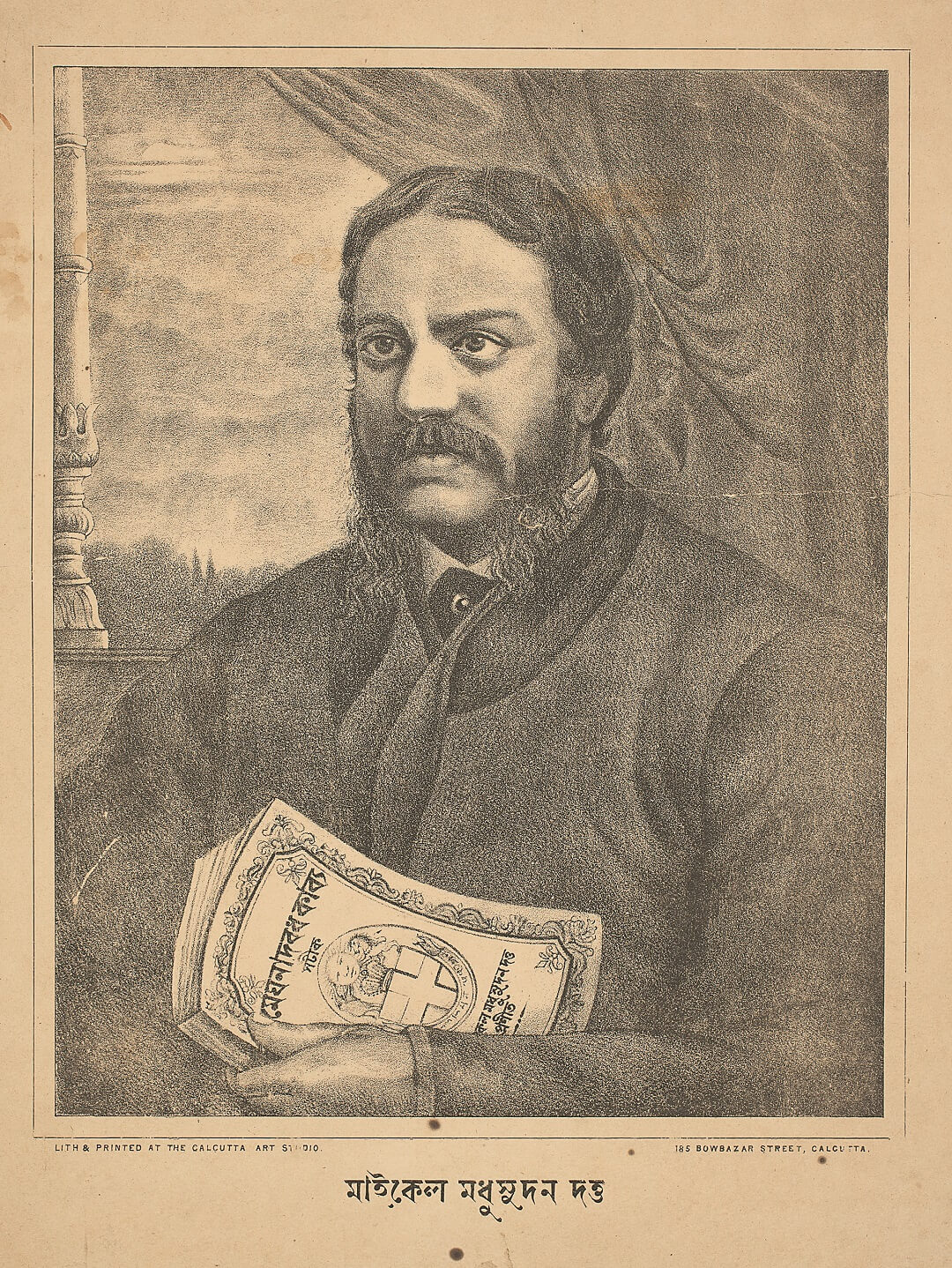

Calcutta Art Studio

Michael Madhusudan Dutt

Lithograph

The first attempts at indigenous printmaking began with book illustrations. In 1816 Ramchaund Ray’s name appears below the metal engraved illustrations in Bharatchandra Ray’s Oonoodah Mangal. Ramchaund Roy was trained in the miniature tradition and developed a very distinct style of engraving and began illustrating a considerable number of books as the demand increased. In this image from Radhamohan Sen’s Sangit Taranga we observe two ragas—Deepak and Bhairavi visualised through a deft use of the aquatint. Annoda Prasad Bagchi, a student of the newly founded School of Industrial Art and trained in a wide array of printmaking techniques, made his living by illustrating posters, books and journals. Quitting his day job, he founded the Calcutta Art Studio in 1876, which soon became one of the most popular printmaking studios of the city. |

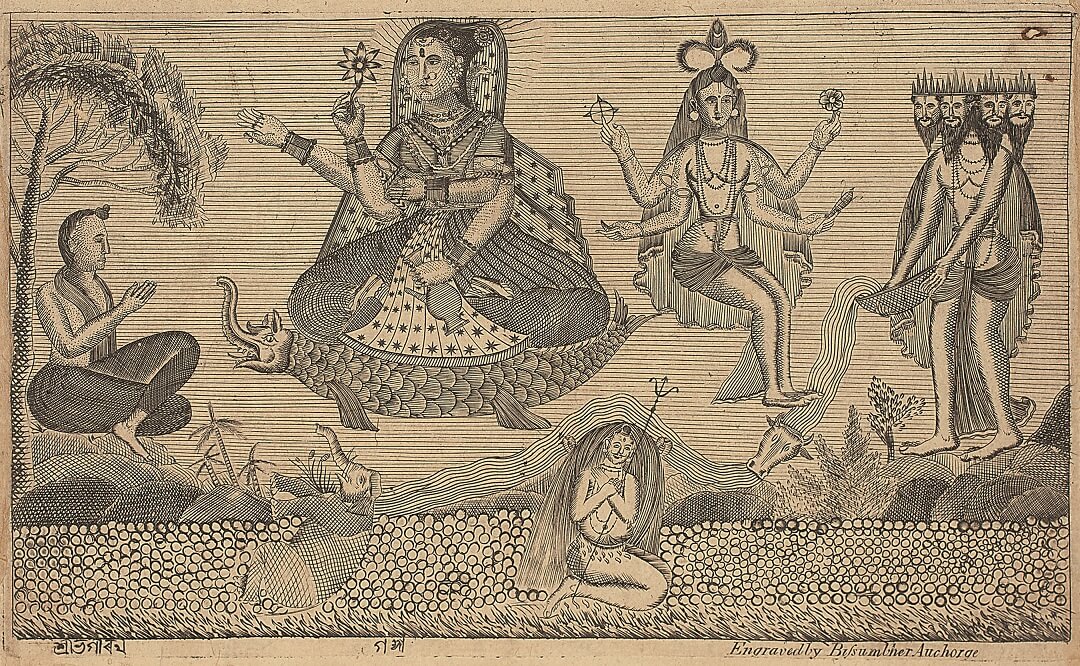

Bisumbher Auchorge (Vishwambhara Acharya)

Shri Bhagirath and Ganga

Ramchaund Roy

Bag Tayyab/Bhairav Raga

Chore Bagan Art Studio

Sri Sri Hara Parbati

In this series of images, we see the transition from two-dimensional illustrations to early attempts at endowing mythological scenes with volume and perspective. Bat-tala printers struggled to create depth. By the end of the 19th century, art school trained painters familiar with European conventions of drawing and colouring flooded the market for cheap printmaking, displacing the metal and wood engravers from Bat-ala. They brought in the three-dimensional tactile naturalism of oil paintings, in cheaply printed oleographs, and chromolithographs.

Kansaripara Art Studio

Manada Sundari

Oleograph

Chore Bagan Art Studio

Sushila Sundari - Modesty

Oleograph

Techniques of producing coloured prints led to further demand for printed pictures. According to a popular anecdote, the Calcutta Art Studio in Bowbazaar acquired a lithography press where prints could be directly taken in colour in the 1870s. But the colours turned out to be exaggerated and garish as the printers did not know how to balance them. This led to the emergence of a distinct popular iconography, setting the language of popular prints produced in the new studios which came up rapidly around the area. In these two oleographs of Kumada Sundari and Manada Sundari, derived from the popular tradition of courtesan paintings of Kalighat, the artist uses loud colours on female bodies to titillate the audience. |

Raja Ravi Varma

Draupadi - Sudeshna

Raja Ravi Varma

Shakuntala Patralekhan

Raja Ravi Varma

Shakuntala Janam/ Birth of Shakuntala

Artists like Raja Ravi Varma were trained in the European academic style of painting. He tapped into the popular demand for printed pictures of gods and goddesses and sought to reform the garishly coloured prints emerging from contemporary studios by developing a more refined, naturalistic iconography of religious and mythological scenes. Ravi Verma’s contribution was so enduring that figurations he created for myths and epics continue to inform our popular imagination of gods and goddesses today.

|

INSTITUTIONAL CHALLENGES: PRINTMAKING IN THE ART SCHOOLS Art colleges sprang up in the major cities in colonial India around the mid 19th century. Their curriculum was designed to produce skilled technicians and craftspersons, who could help the industrial arts grow, and students were trained with this purpose in mind. Printmaking remained confined within this limited educational vision until a section of Western educated elite Indians began joining the art schools. Some of them also hailed from intellectual communities that were already involved in the nationalist movement and had begun to build a new language of anti-colonial resistance. |

|

Radha Charan Bagchi Before the Rains, Lalgola Ghat Etching and aquatint |

Hiranmoy Roychaudhuri

Untitled

V. S. Adhurkar

Untitled

Hiranmoy Roychaudhuri

Untitled

Printmakers like Hiranmoy Rowchury and the V. S. Adhurkar produced visually stunning lithographs even though their craft remained largely confined within the conventions of academic art.

|

NEW EXPERIMENTS: SHANTINIKETAN AND MODERNIST PRINTMAKING Aesthetic modernism took a distinctly anti-colonial shape in Bengal under the influence of the three Tagore brothers—Abanindranath, Gaganendranath and Samarendranath—as they sought to create a language of artistic expression outside the European conventions taught in the art schools. The three brothers transformed the South verandah of the Jorasanko residence in north Calcutta into an artists’ salon called the Bichitra Studio. The community of artists which flocked to this studio, experimented, among other things with various printmaking techniques to explore possibilities outside those made available by the formal art institutions. |

|

Mukul Dey Drawing the Net, Karatoa River, Pabna, East Bengal Drypoint |

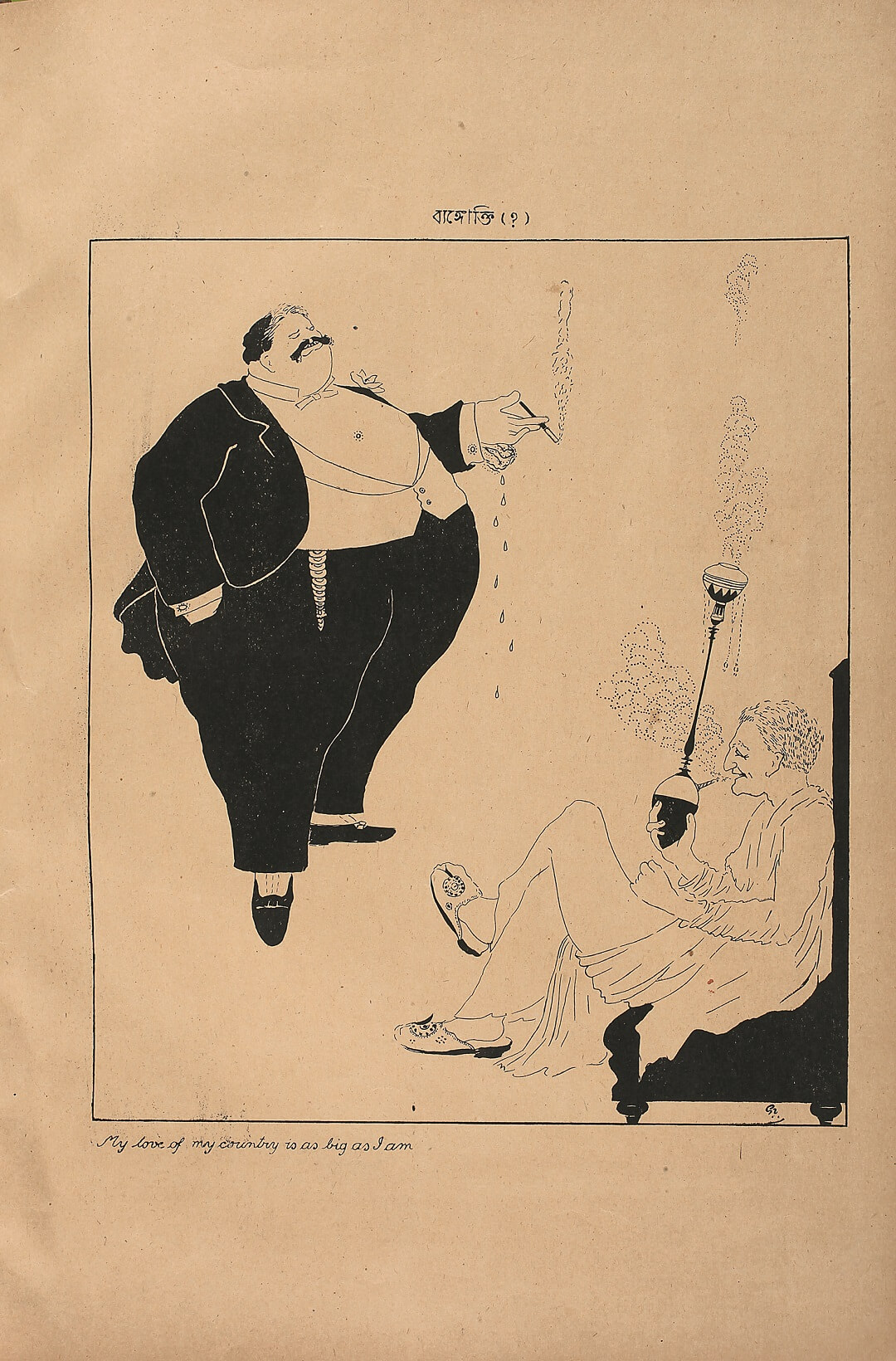

Gaganendranath Tagore

My Love for My Country is as Big as I Am

Chromolithograph

Adbhuth Lok (1917)

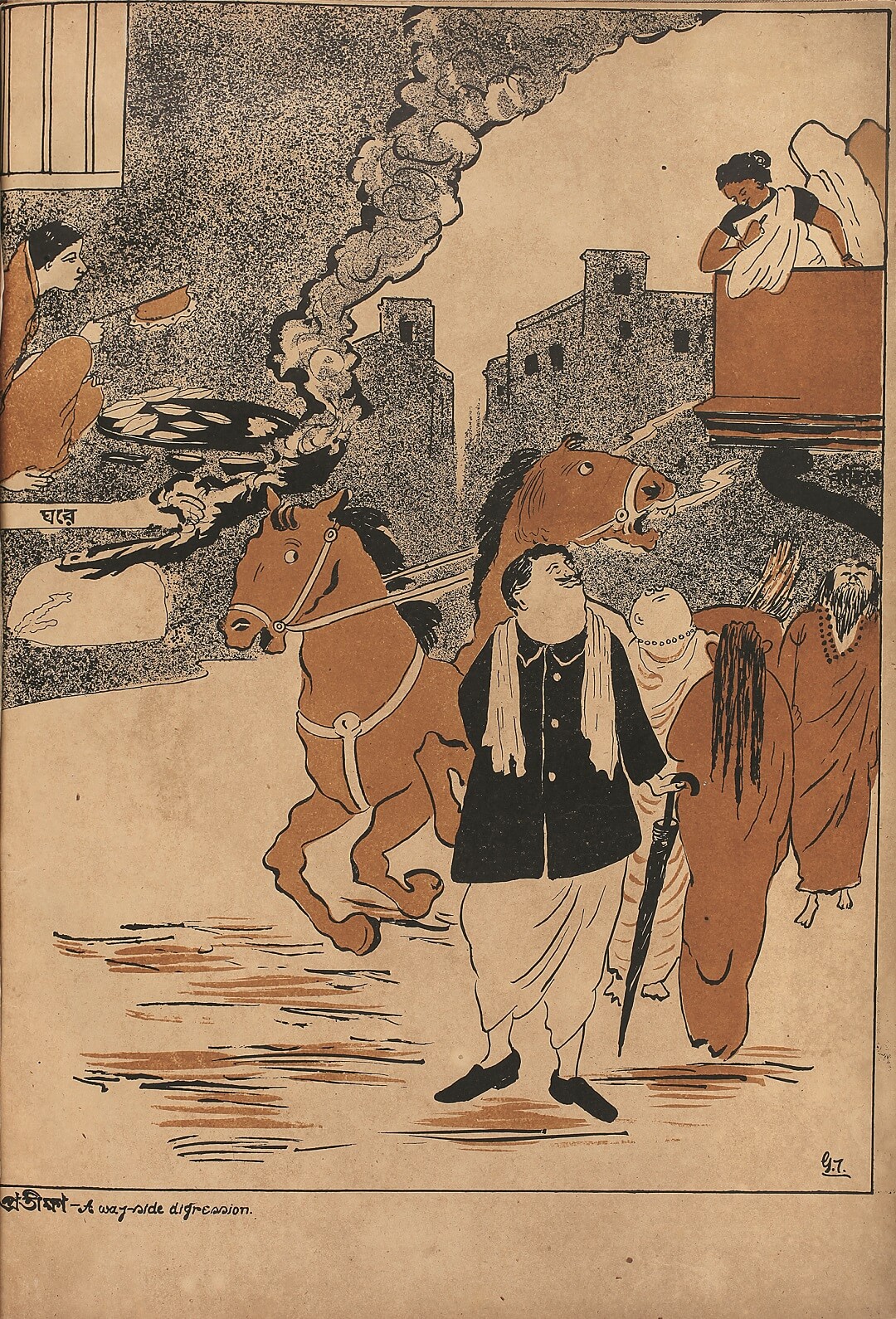

Gaganendranath Tagore

A Wayside Digression

Chromolithograph

Adbhuth Lok (1917)

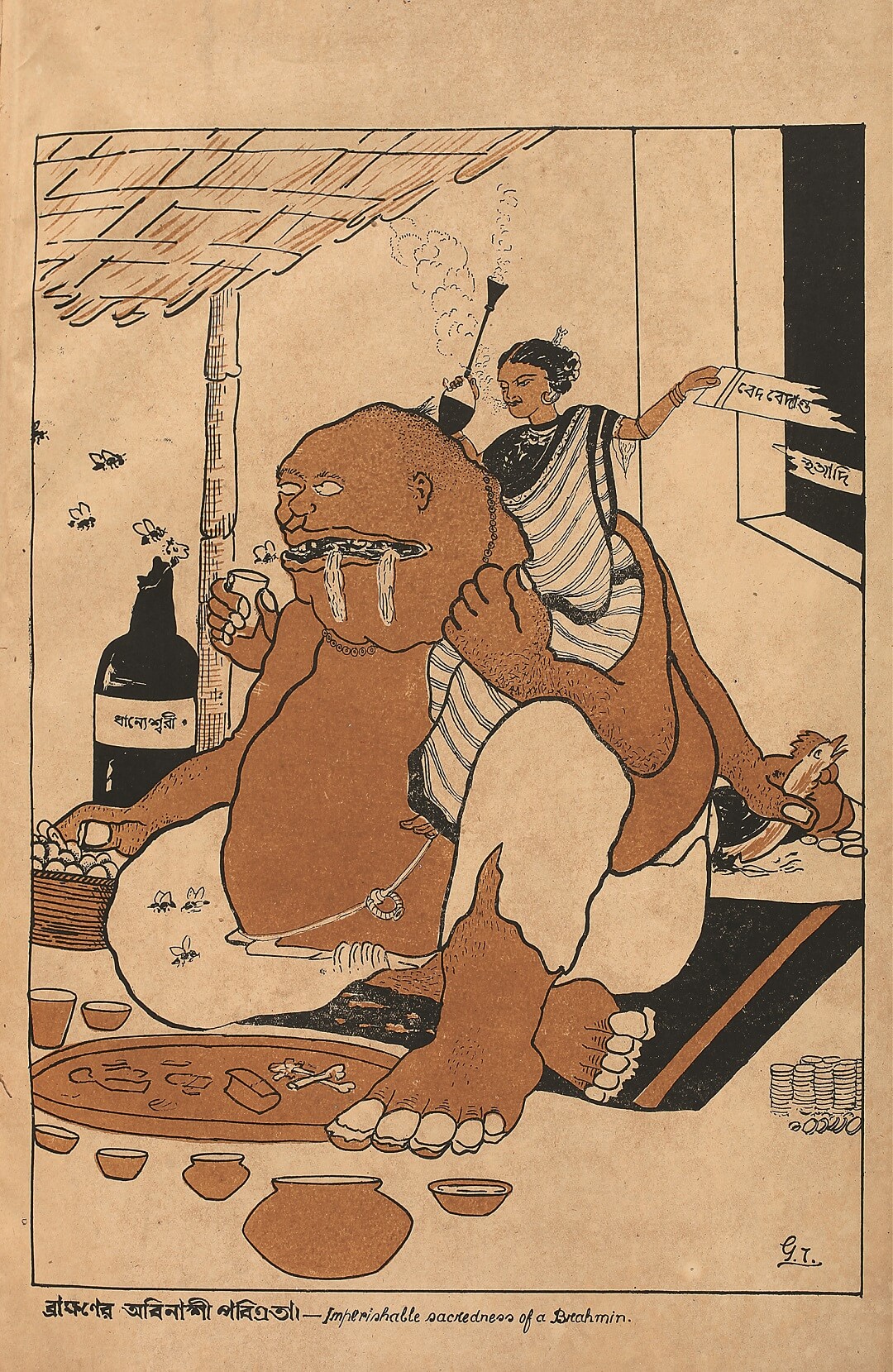

Gaganendranath Tagore

Imperishable Sacredness of a Brahmin

Chromolithograph

Adbhuth Lok (1917)

Gaganendranath Tagore is considered one of the first practitioners in India who used printmaking as a practice in its own right instead of merely using it as a medium of reproduction. In 1915, he purchased a lithographic handpress, later known as the Bichitra Press, where he began to print incisive political cartoons to lampoon the colonial authorities and orthodox Hindu society alike. Between 1915 and 1921 Gaganendranath published three lithographic cartoon albums—Adbhuth Lok (1915), Birup Bajra (1917) and Naba Hollud (1921), a first of its kind endeavour in the country. |

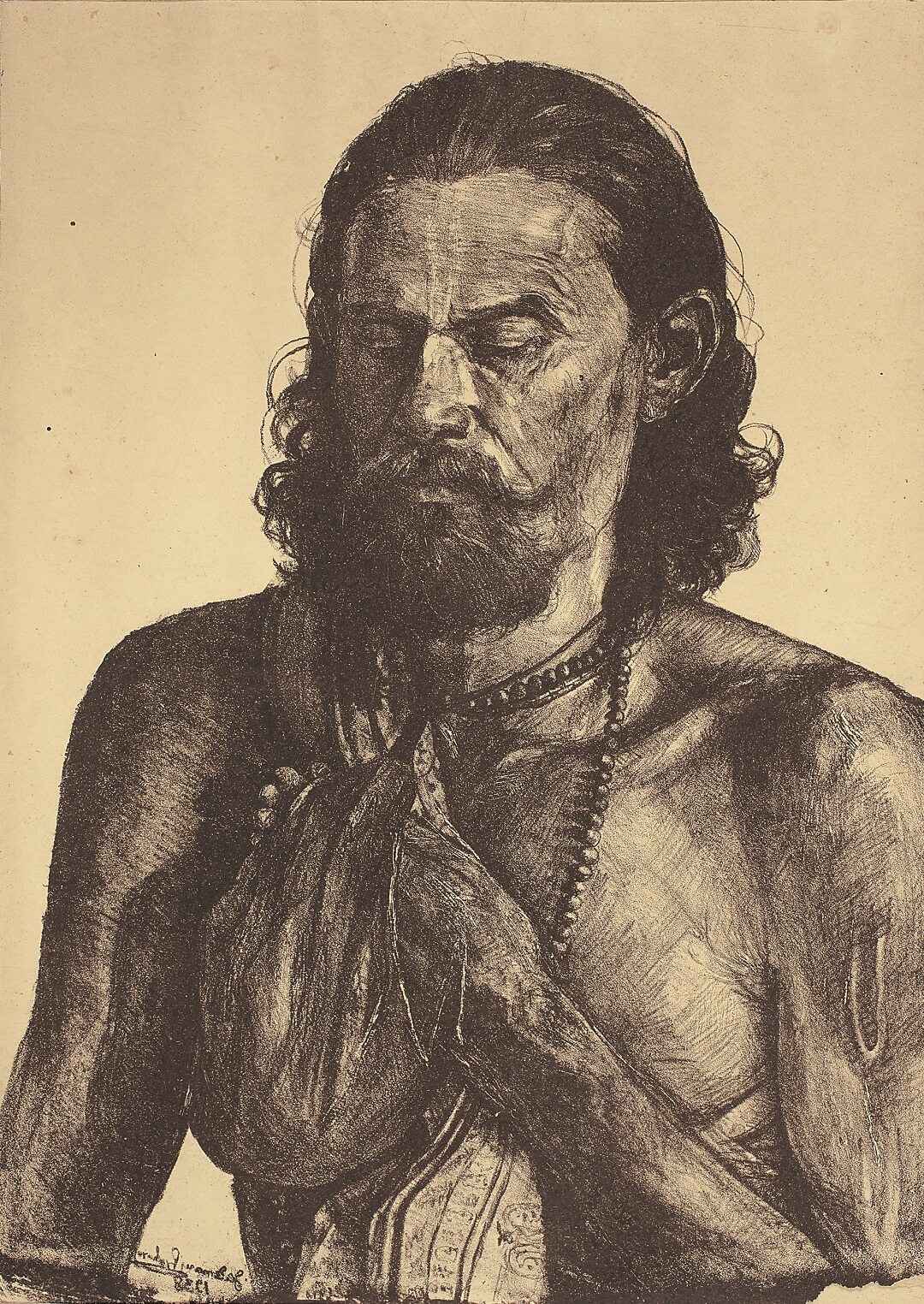

Mukul Dey

Dancing Apsara

Mukul Dey

Col. Pirwan

Mukul Dey

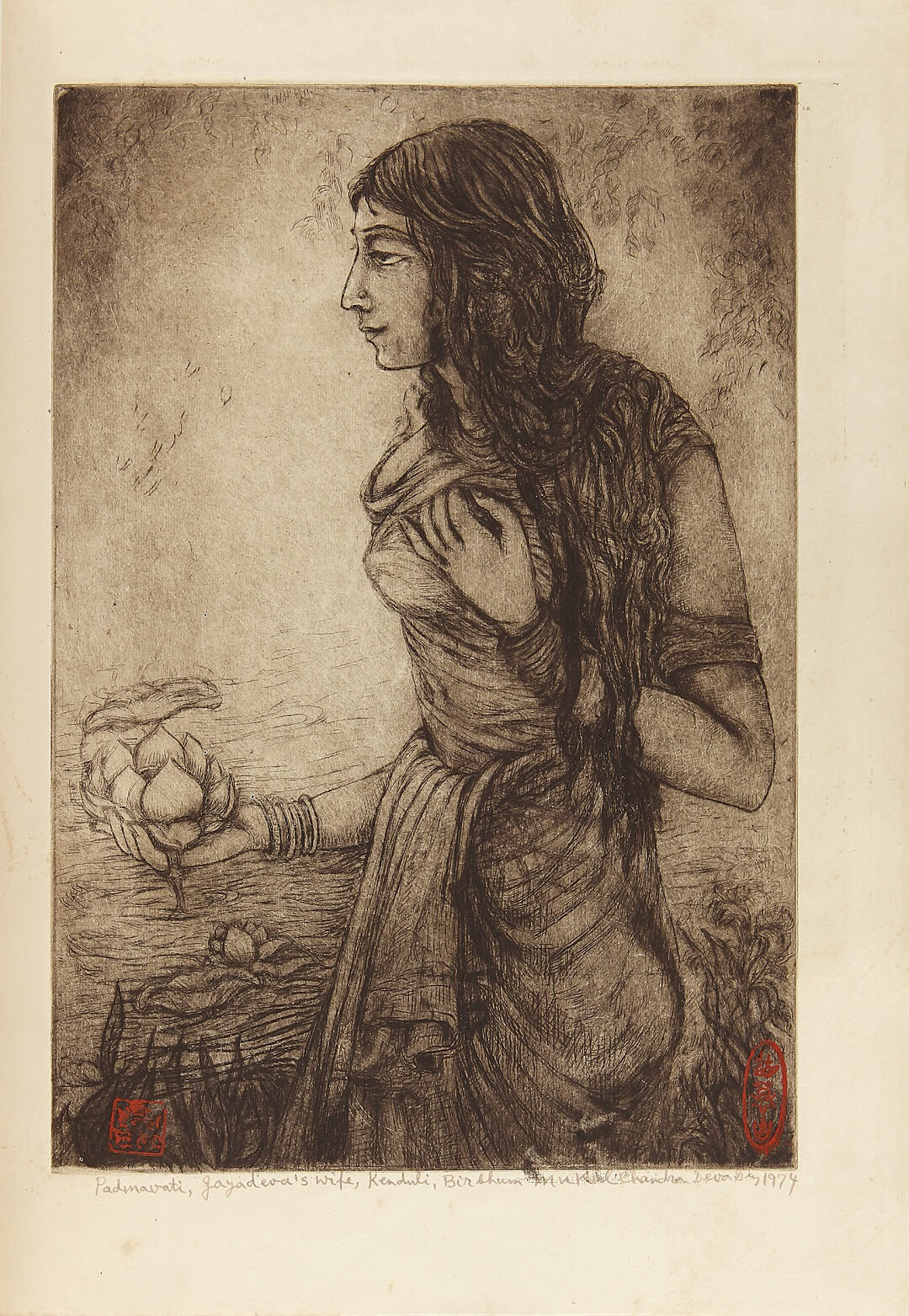

Padmavati, Jayadeva’s Wife, Kendall Birbhum

Mukul Dey returned from the USA in 1916, going on to play a pioneering role in creative printmaking in India. He had a keen sense of light and shade and created similar effects in his drypoint etchings, drawing on the aesthetic of the Bengal School.

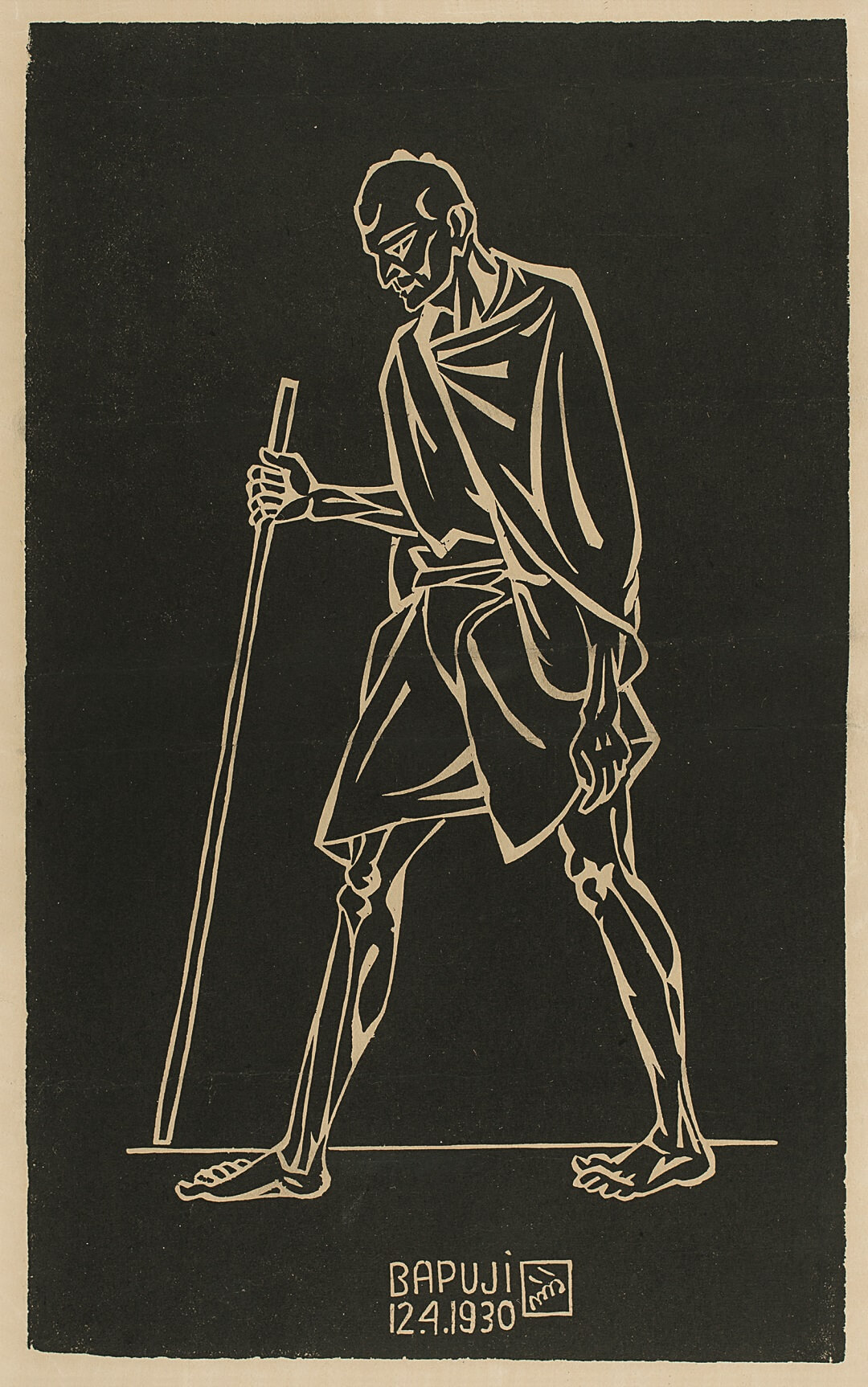

Nandalal Bose

Bapuji

Linocut

Nandalal Bose

Untitled

Linocut on rice paper

Nandalal Bose

Untitled

Drypoint and etching

In the early 1920s, Nandalal Bose became the principal of Kala Bhavana and introduced graphic art to the curriculum. In 1924, his visit to China and Japan exposed him to monochrome and multicolour woodcut prints and he returned with a rich collection of Chinese rubbings. He was striving to develop a language of printmaking which would not be dictated by the demands of aesthetic realism. While his subjects remain realistic, their formal structure consciously veers away from perspectival depth, drawing generously from the hitherto unexplored vocabulary in Indian printmaking such as Calcutta woodcuts, bold clear divisions of Japanese woodcuts and others. |

Benode Behari Mukherjee

Untitled

Benode Behari Mukherjee

Untitled

|

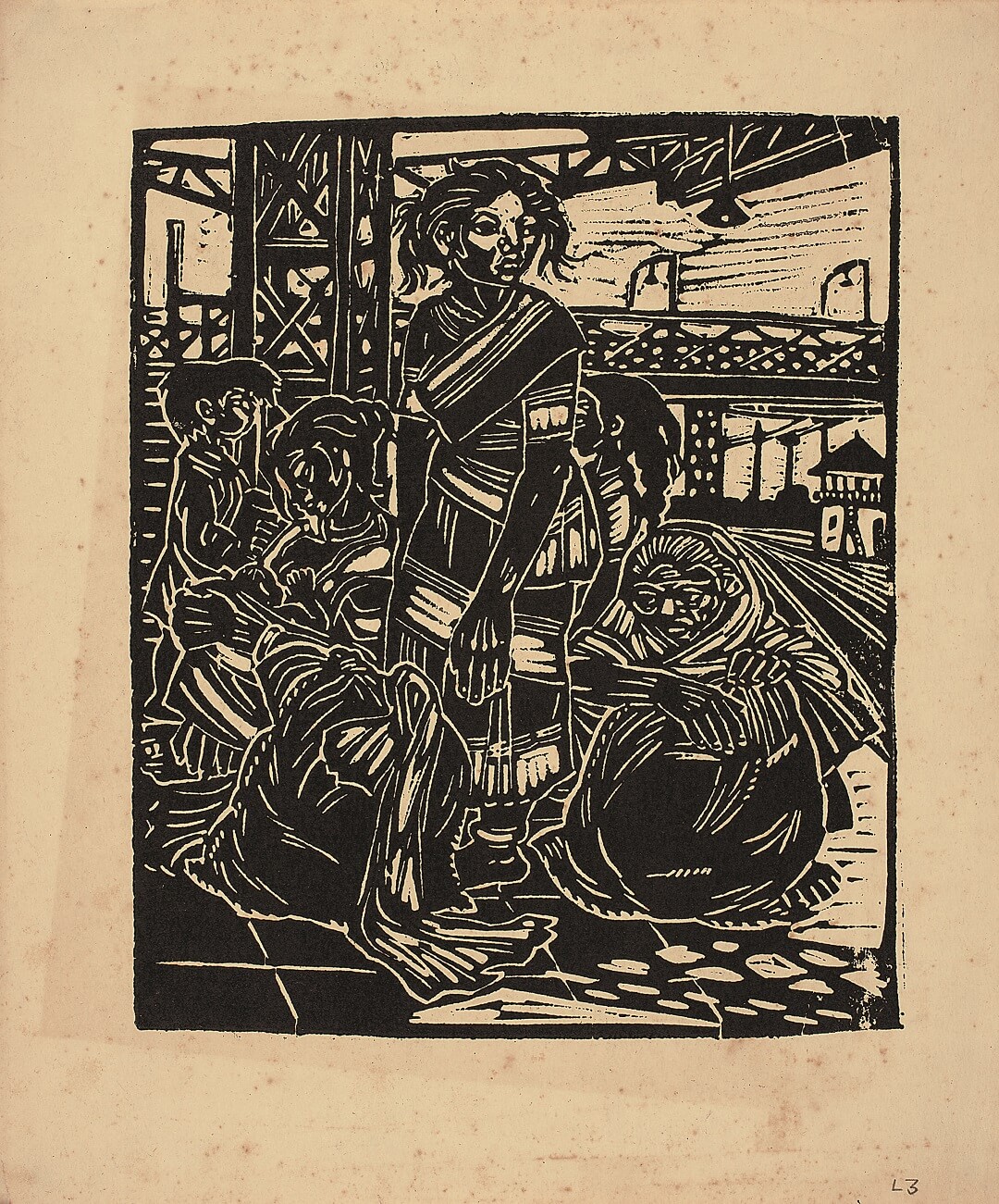

UNIQUE VOICES: DIVERGENT LEGACIES OF INDIAN PRINTMAKERS In the next few sections we will explore the enduring legacy of printmakers from diverse traditions. From Haren Das’s academism to Chittaprosad and Somnath Hore’s attempt to use printmaking as a medium of social and political activism, the technology has come a long way from simply being a method of reproduction to emerging into an art form of its own. |

|

Somnath Hore Untitled Pulp print |

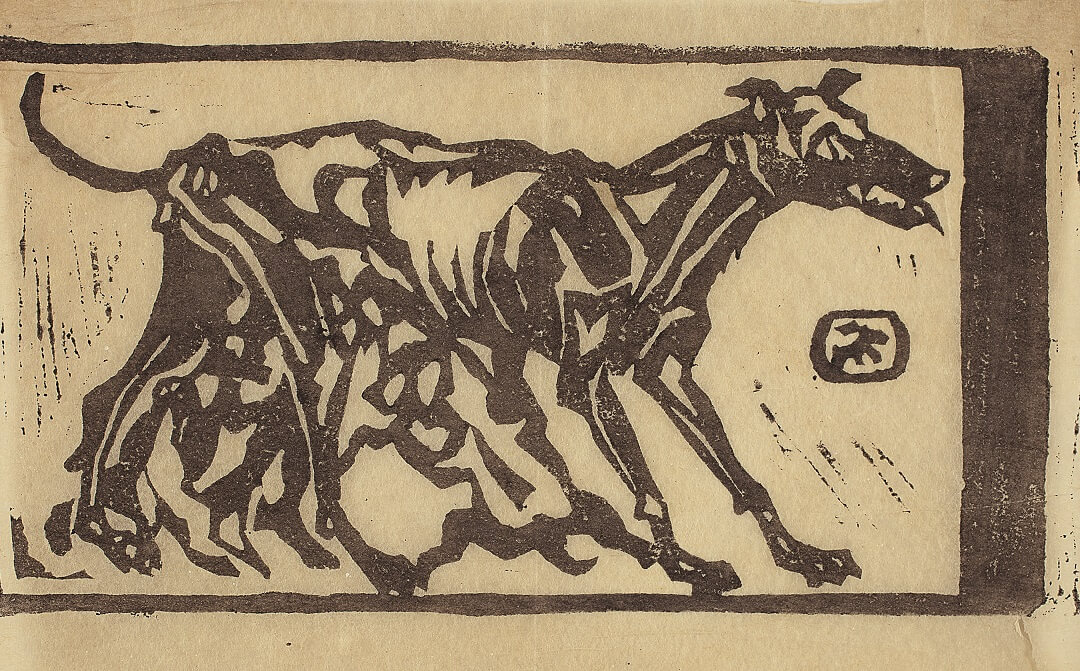

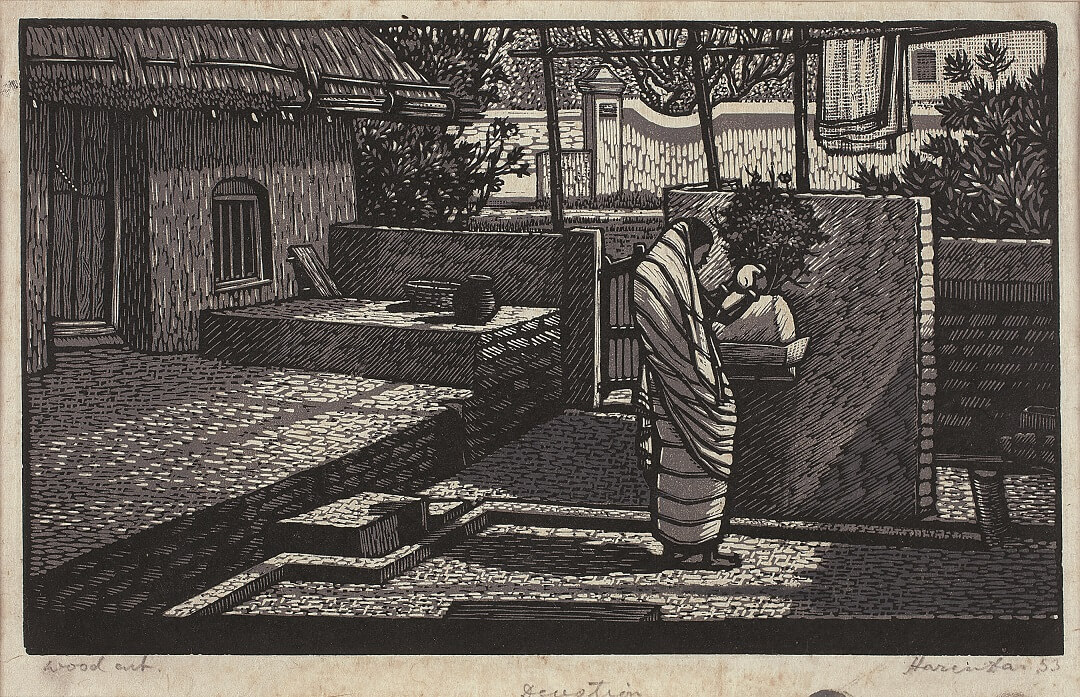

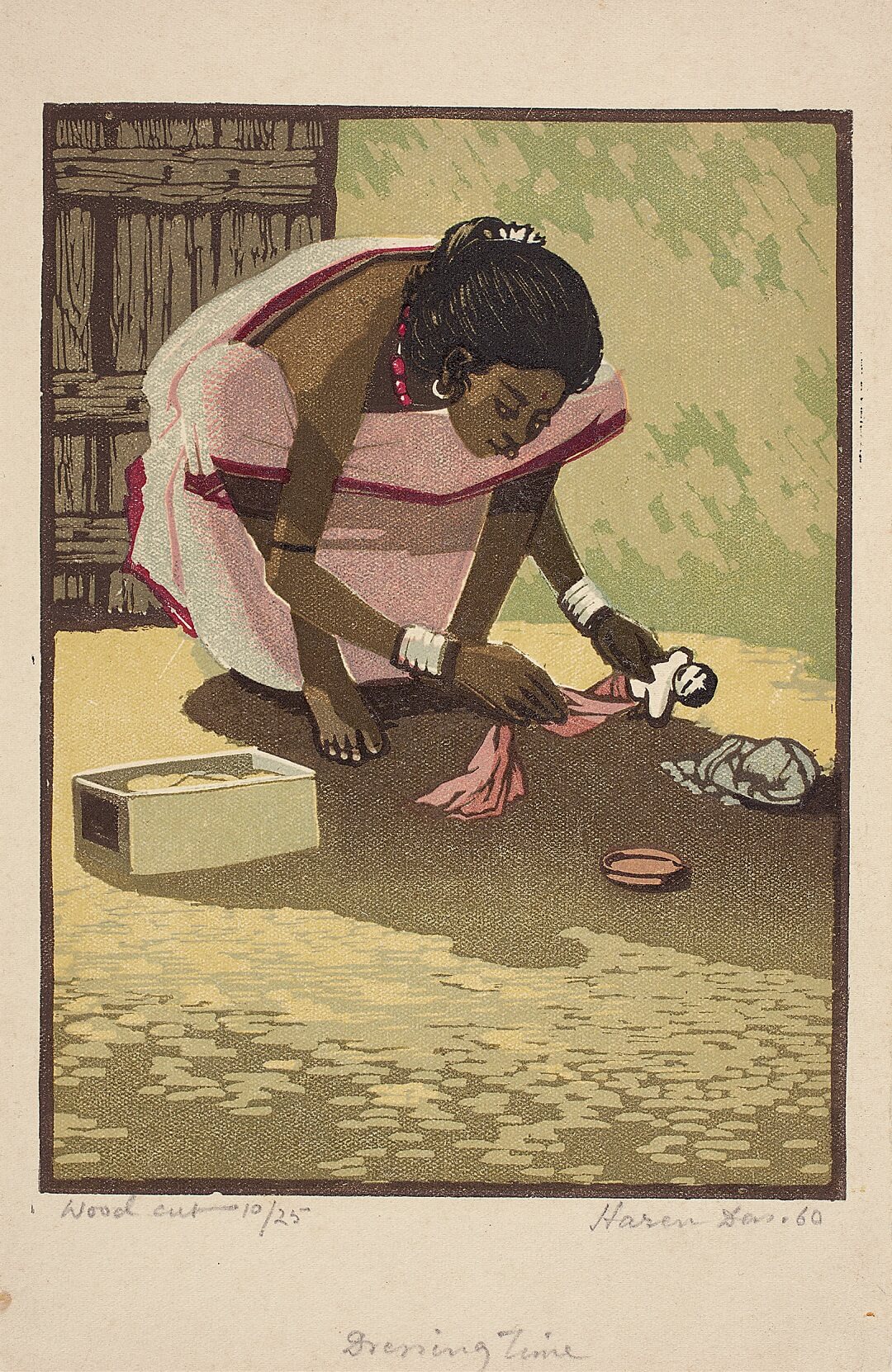

Haren Das

Devotion

Woodcut

Haren Das

Wandering Minstrels

Lithograph

Haren Das

Dressing Time

Woodcut

Haren Das's work exemplifies the dilemma that Indian printmakers were faced with: whether to continue with their Western naturalistic art training and produce images with popular acceptability, or to experiment with composition and technique, as printmakers in Santiniketan were doing. Das appears to have opted for the former. With some of his contemporaries, like Shaffiuddin Ahmed, who pioneered the graphic art movement in Bangladesh, he remained true to his training, evoking nostalgia for a style that his contemporaries were outgrowing, creating exquisitely detailed scenes from everyday life. |

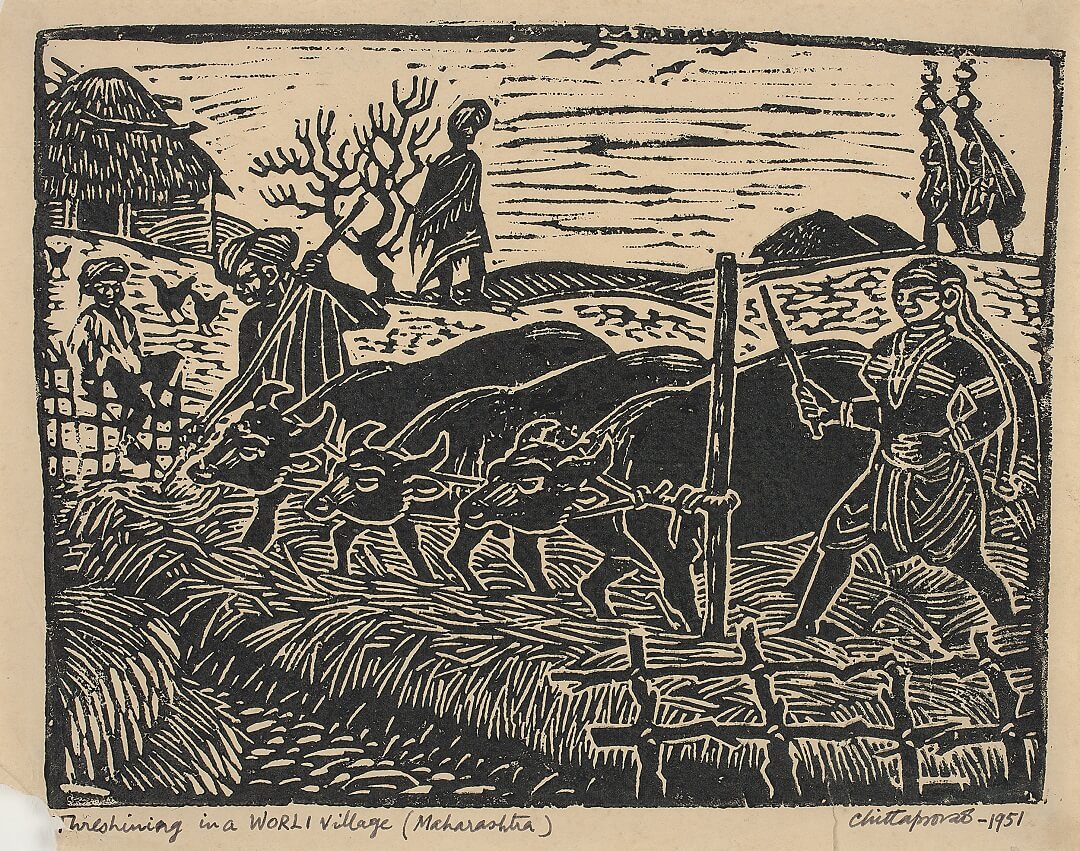

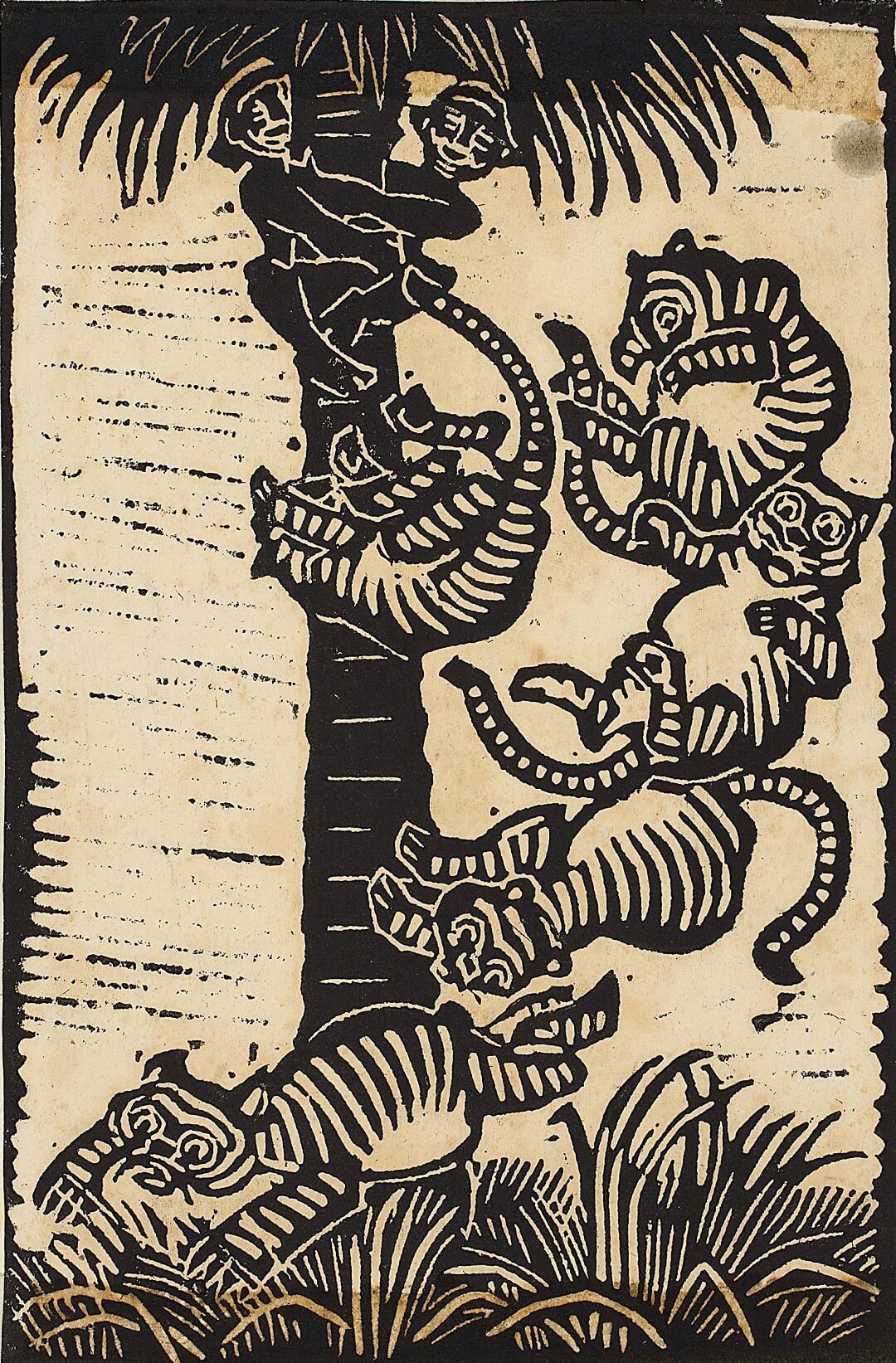

Chittaprosad

Threshing in Worli village (Maharashtra)

Chittaprosad

Scene from a Fairy Tale

Chittaprosad

Untitled

|

Somnath Hore looked at the ceaselessly suffering human body, living through the traumatic violence of communalism, poverty, hunger and dispossession, and tried to embody it through the very process of printmaking—the act of incising the plate re-enacting the violence and pain. Like Chittoprosad, he used printmaking techniques as a tool of social and political critique. |

|

Somnath Hore Flood Lithograph on paper Somnath Hore Untitled Etching and engraving |

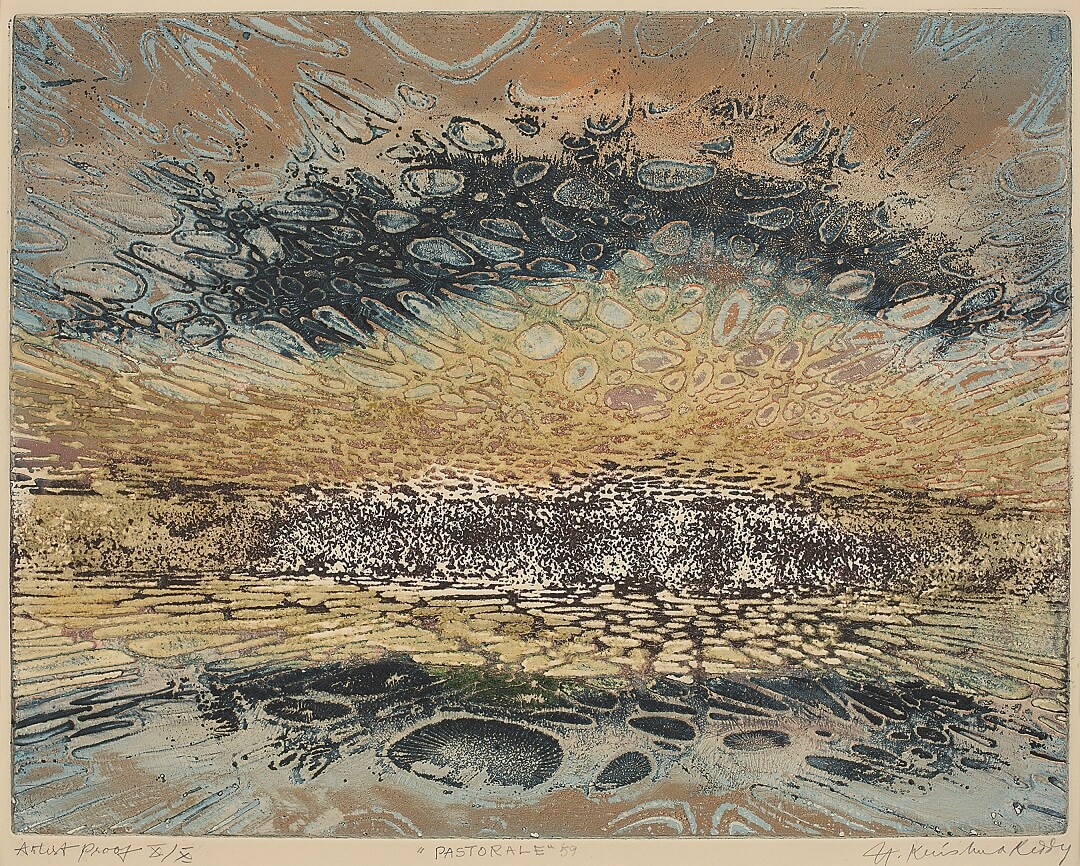

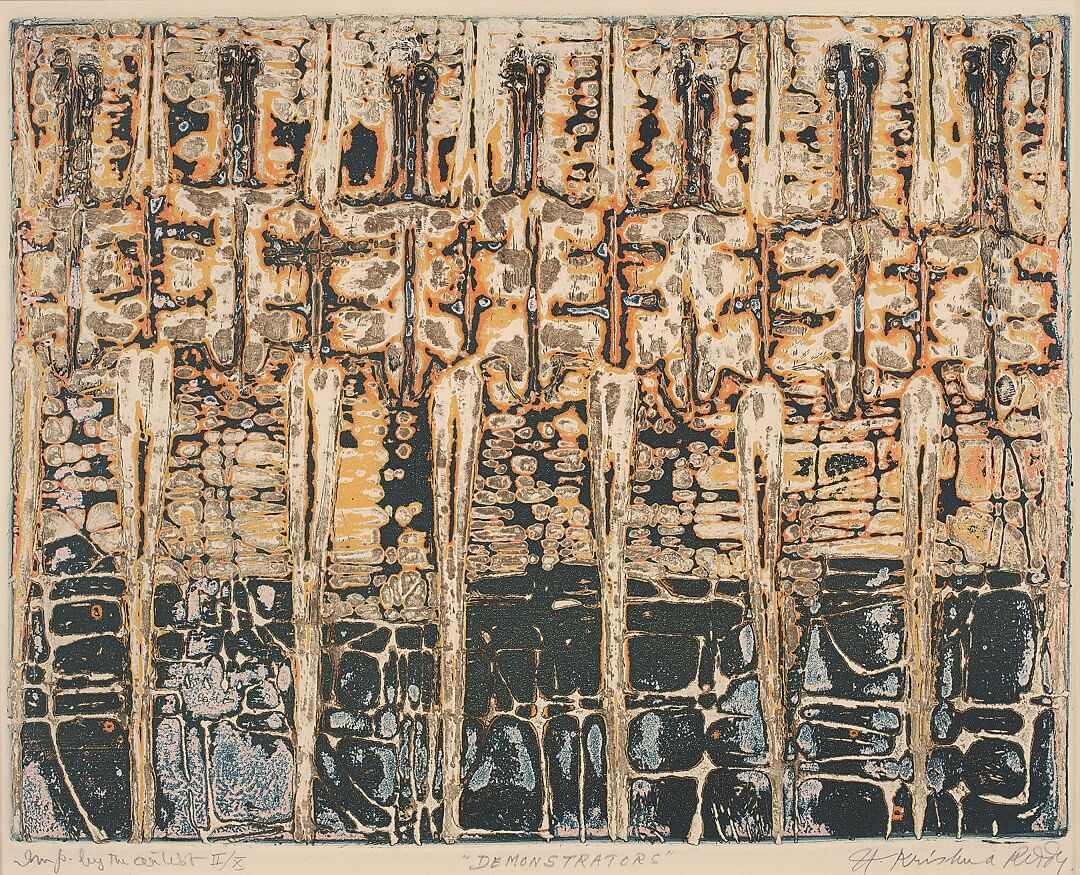

A. Krishna Reddy

Pastorale

Viscosity

A. Krishna Reddy

Le Clown Célèbre

Colour etching

A. Krishna Reddy

Le Clown Celebre

Colour etching

Krishna Reddy used the technique of viscosity to craft a language of spiritual abstraction. Most printmakers of the modernist generation encountered Reddy and viscosity as a technique either at Atelier 17 in Paris or in the several workshops that he conducted across India in the 1980s. |

|

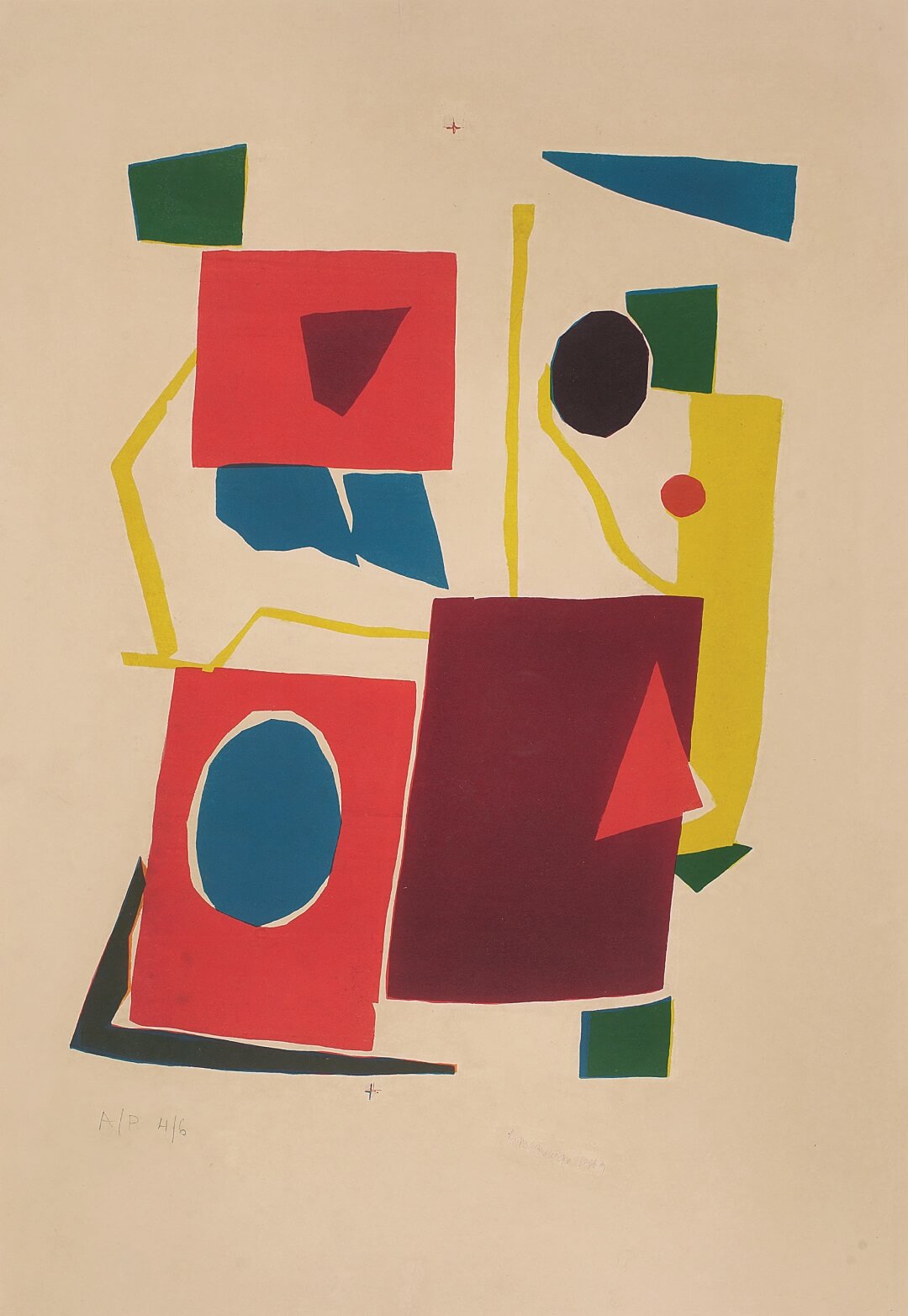

COMMUNITY EFFORTS: PRINTMAKING IN THE 20TH CENTURY From the 1950s onwards printmaking largely developed as a community activity in institutions or artists’ initiatives in various regions of the country like Bombay, Baroda, Calcutta, Santiniketan among others. Gradually public funded and privately sponsored studios emerged to support the growth and sustenance of printmaking in the country. This section offers a sense of the diversity of printmaking practices in the late 20th century. |

|

P. Gouri Shankar Landscape III Viscosity P. Gouri Shankar At Rest Viscosity |

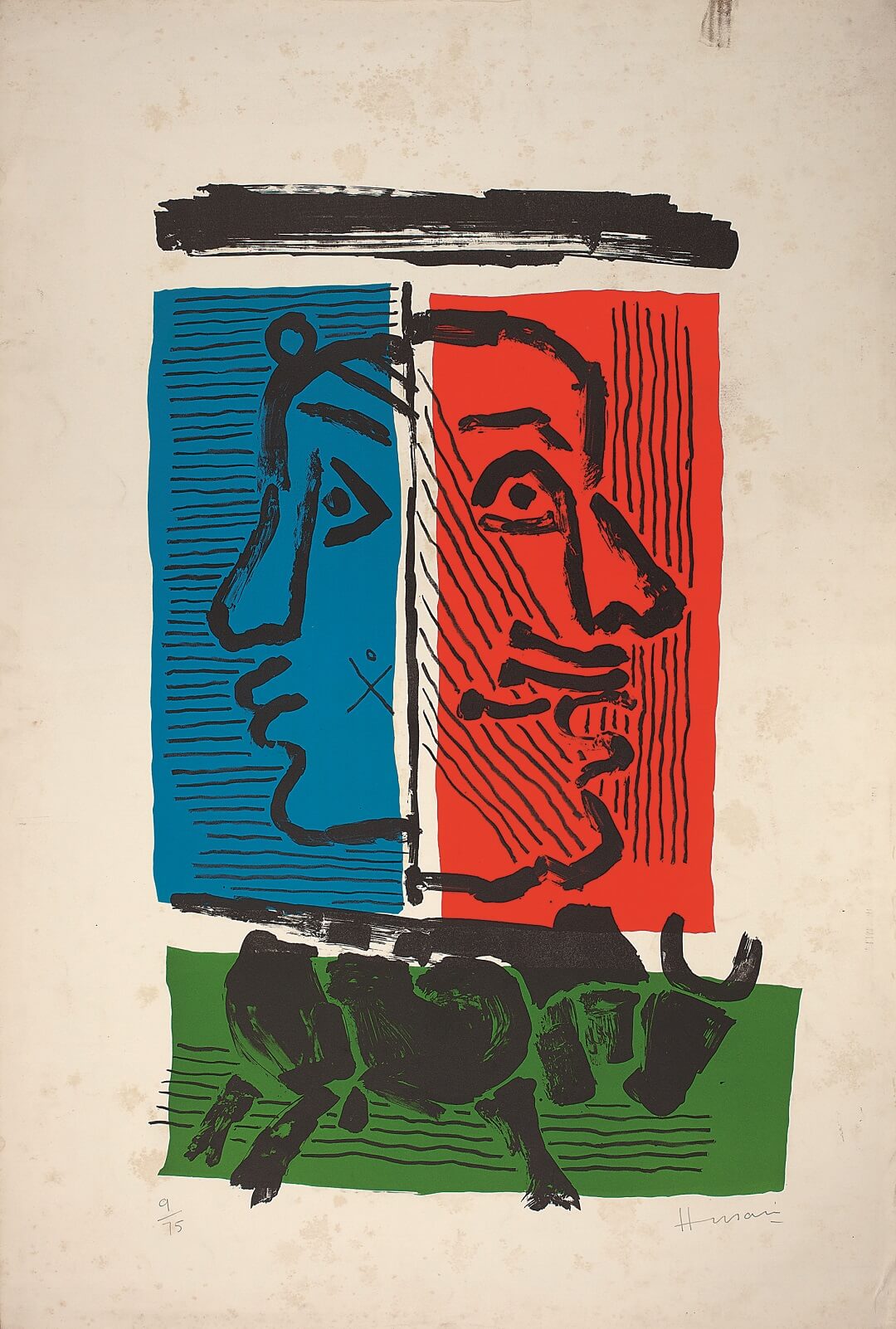

M. F. Hussain

Zoroastrianism

Lithograph

M. F. Hussain

Untitled

Lithograph

Ram Kumar

Two Sisters

Lithograph

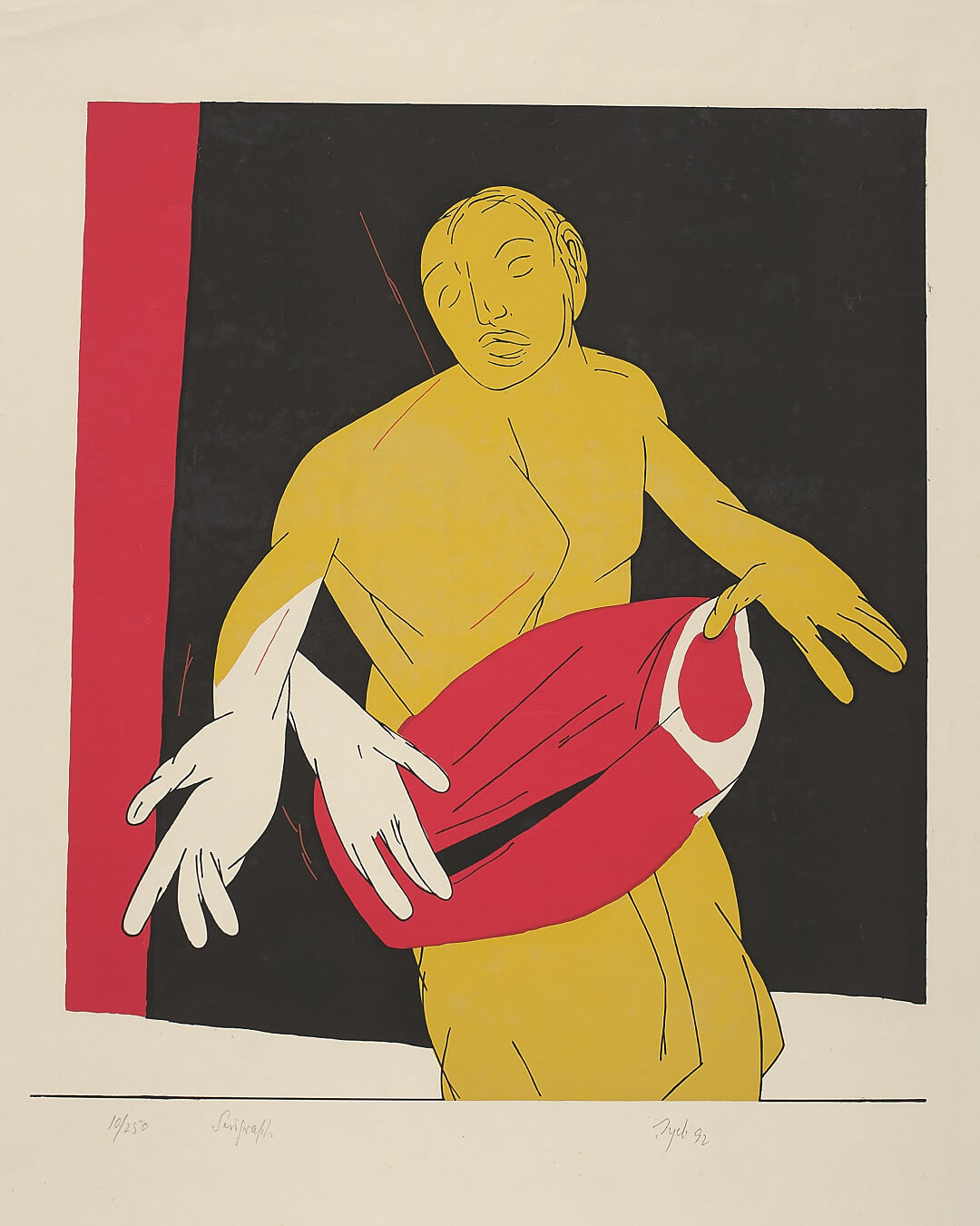

Tyeb Mehta

Untitled

Serigraph

In 1957, the Shilalekh group, including M. F. Husain, Ram Kumar, Tyeb Mehta and V. S. Gaitonde, was established in Bombay. Emulating the highly successful example of Raja Ravi Varma, they began to make lithographs at Mohammedi Fine Arts in Bombay, attempting to sell original works to art lovers at affordable prices. |

Jyoti Bhatt

Images Getting Lost in Oblivion

Vijay Bagdodi

An Unseen Enemy

Jayant Parikh

Untitled

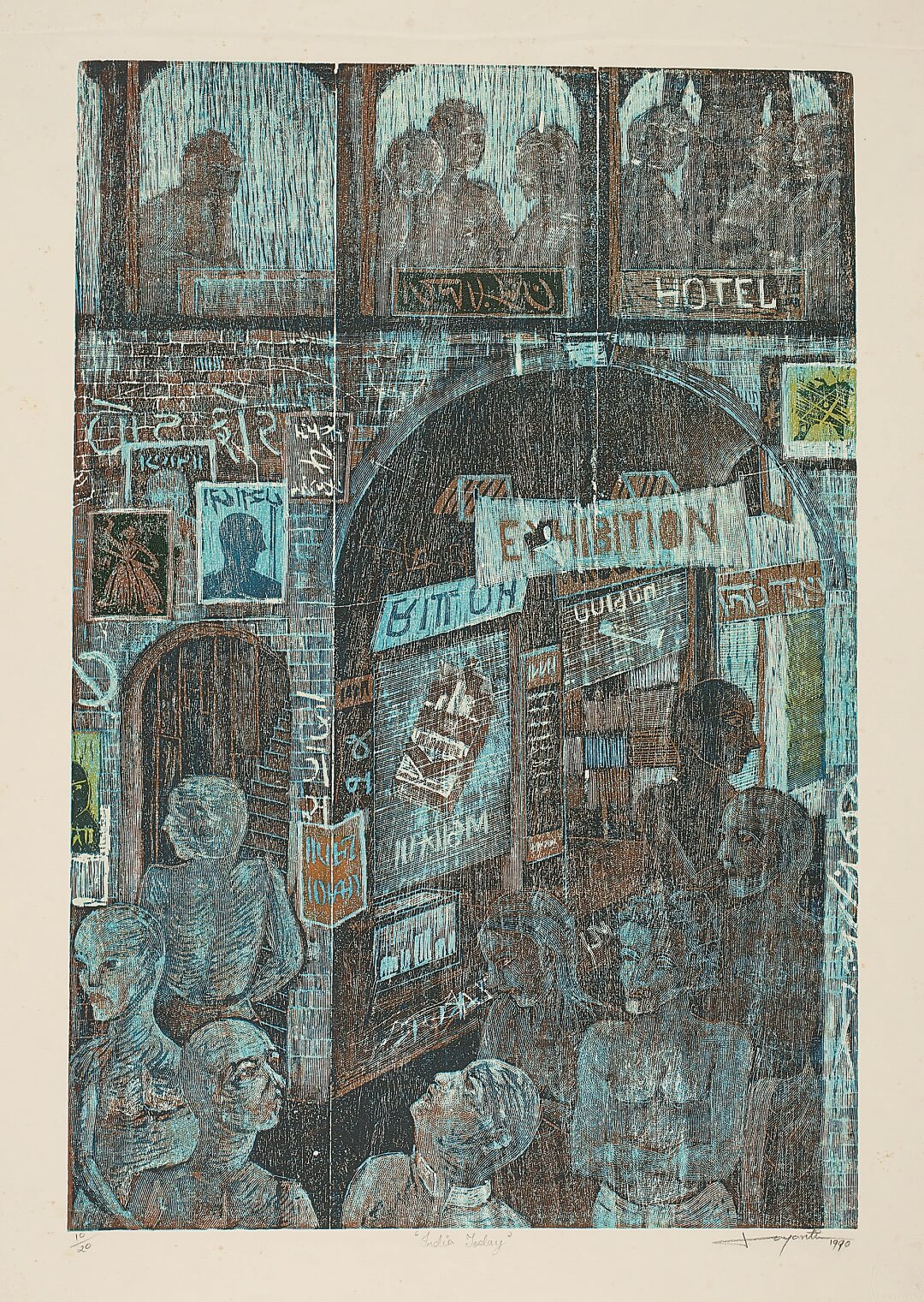

Jayanti Rabadia

India Today

The printmaking section at the Faculty of Fine Arts at Maharaja Sayajirao University, Baroda, was set up in 1950 by N. B. Joglekar. Under his initiative, and later that of Jyoti Bhatt, there was a significant growth of printmaking in the city in the 1960s and early '70s. Jyoti Bhatt, Vinod Ray Patel, V. S. Patel, P. D. Dhumal, Rini Dhumal, Jayanti Rabadia, Vijay Bagodi, Naina Dalal, and Jayant Parikh have remained active contributors to the graphic arts in Baroda.

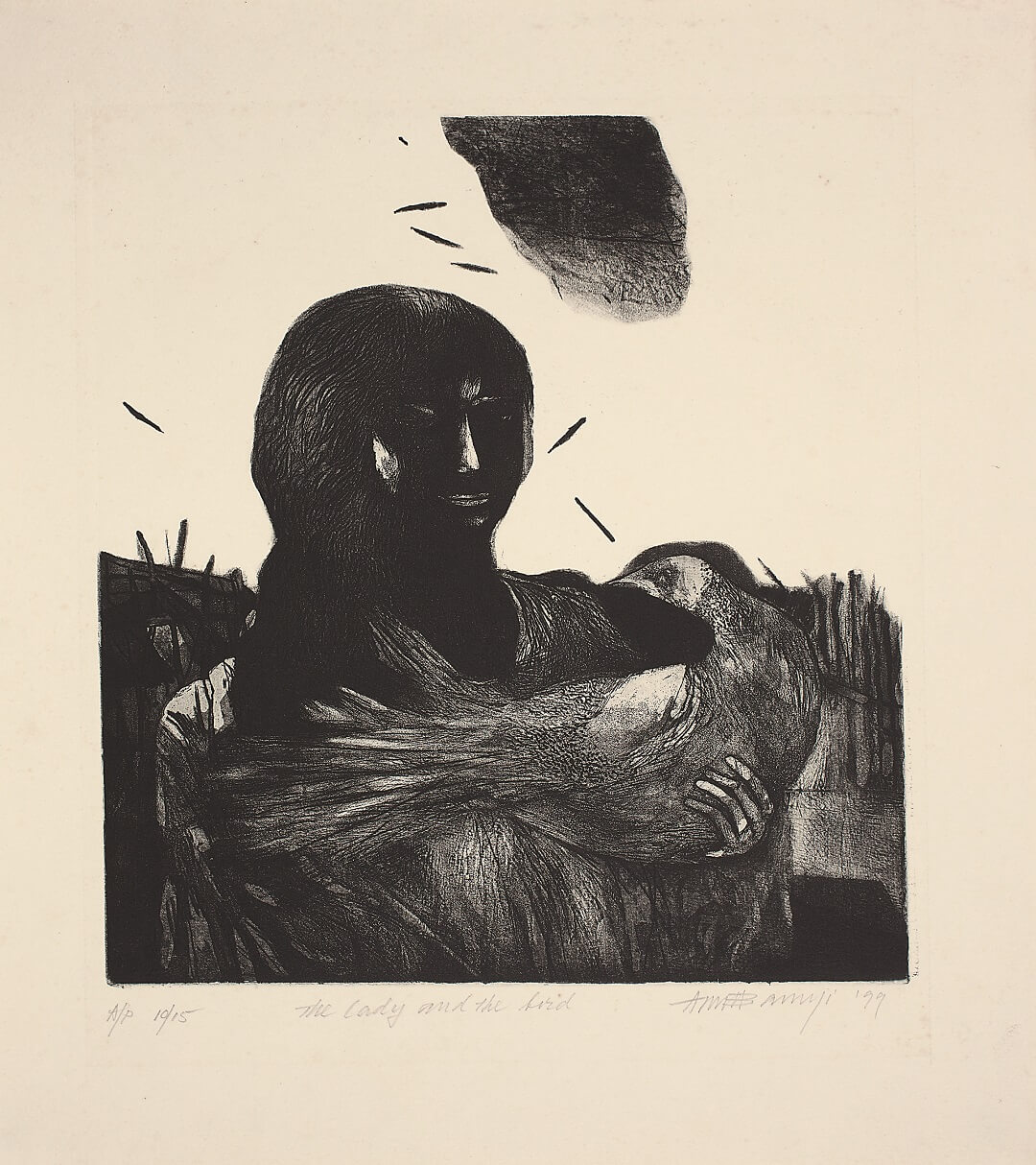

Amitabha Bannerji

The Lady and the Bird

Etching and aquatint

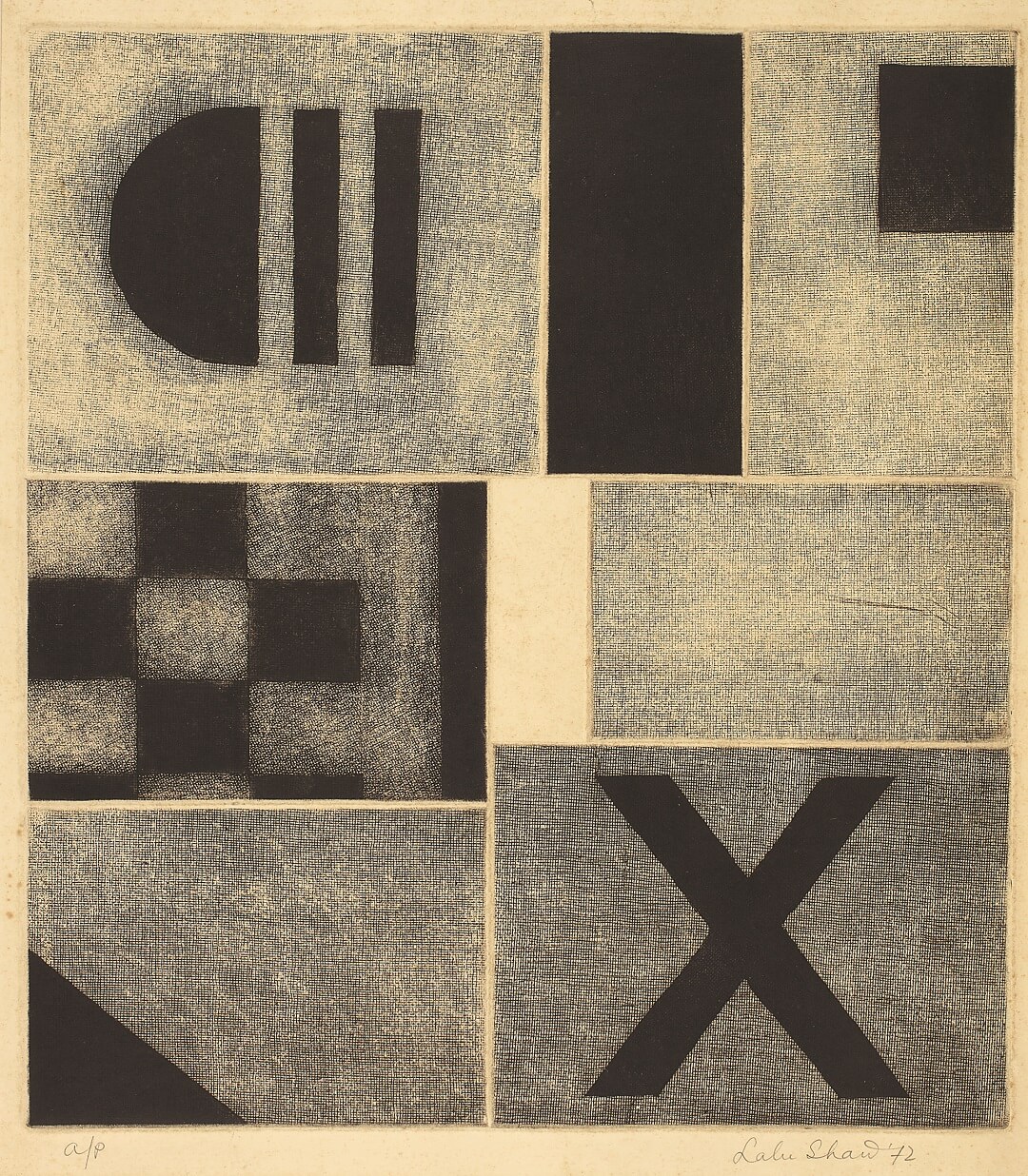

L. P. Shaw

Untitled

Etching and aquatint

Suhas Roy

Untitled

Viscosity

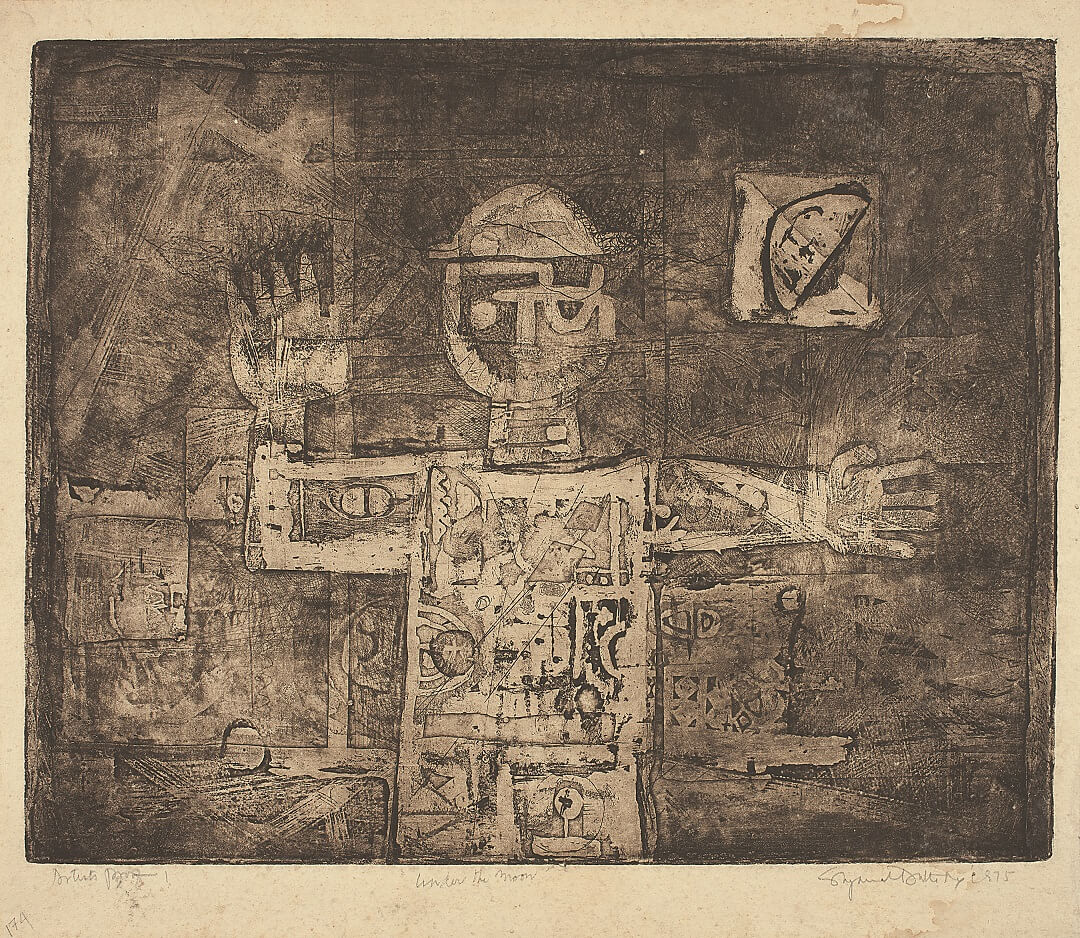

Shyamal Dutta Ray

Under the Moon

Etching and aquatint

In 1960, the Society of Contemporary Artists was established in Calcutta by Sanat Kar, Lalu Prasad Shaw, Shyamal Dutta Ray and later, Amitabha Banerji. Arun Bose, resident in New York, was their mentor and friend. The Society did much to promote the cause of printmaking in India, consistently organising print exhibitions and workshops at different venues across the country from 1960 onwards. Some of these workshops represent significant landmarks in the history of modern printmaking in India. |

Krishan Ahuja

Underwater III

Jagdish Dey

Messenger

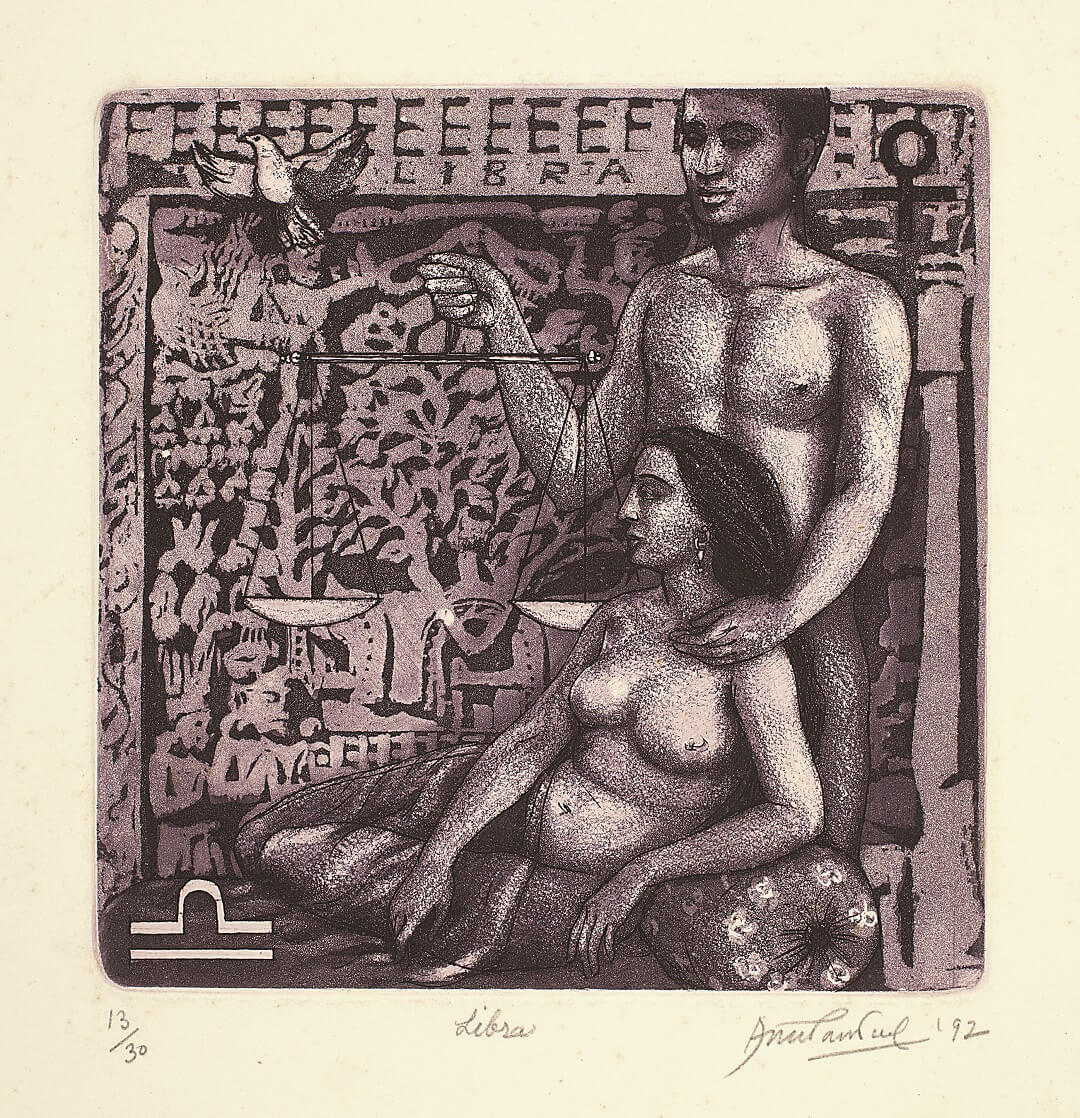

Anupam Sud

Libra (Zodiac Series)

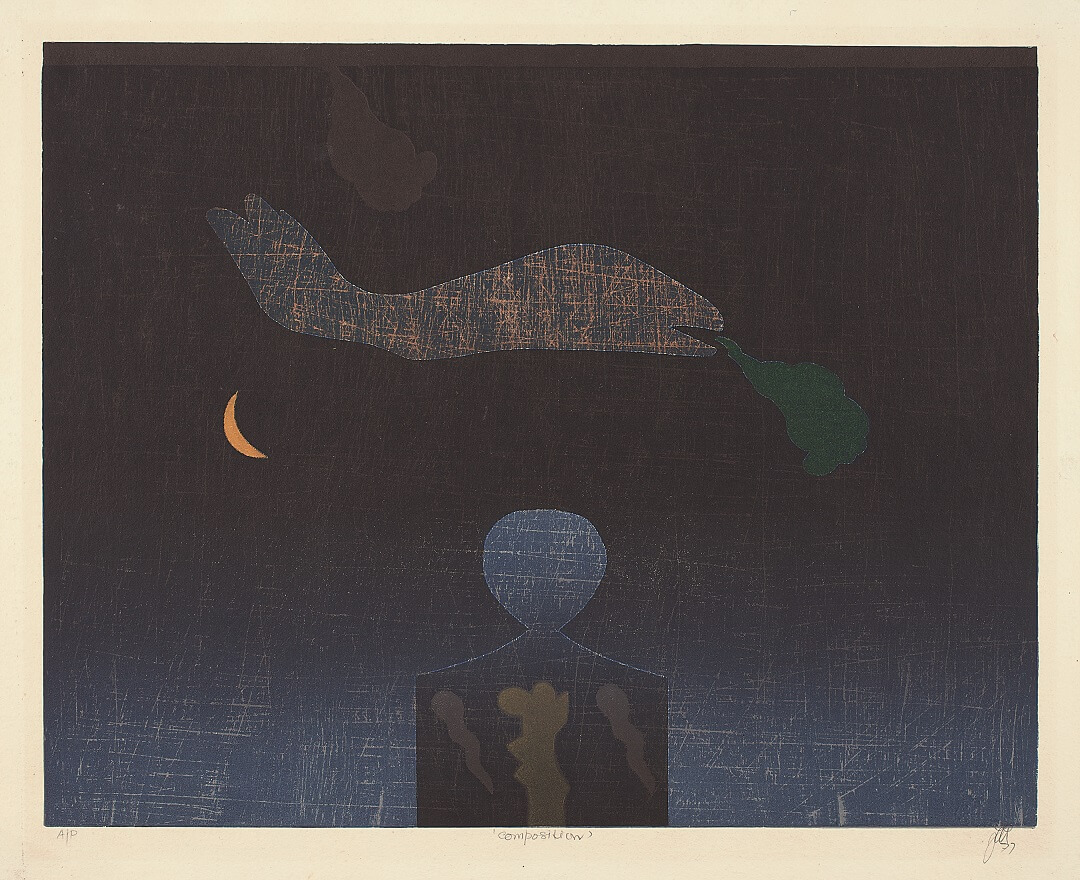

Jai Zharotia

Composition

Jagmohan Chopra proved to be a very significant influence on printmaking in north India, particularly in Chandigarh and Delhi. Highly regarded as a pioneering printmaker, along with his students Anupam Sud, Jagdish Dey, Prashant Vichitra, Paramjit Singh, Krishen Ahuja, Lakshmi Dutta and others, Chopra established Group 8 in 1968. Describing themselves as ‘an association of working artists devoted to printmaking’, the group established a makeshift studio at Shankar Market in New Delhi and organised national-level print exhibitions.

Devraj Dakoji

Untitled

Lithograph

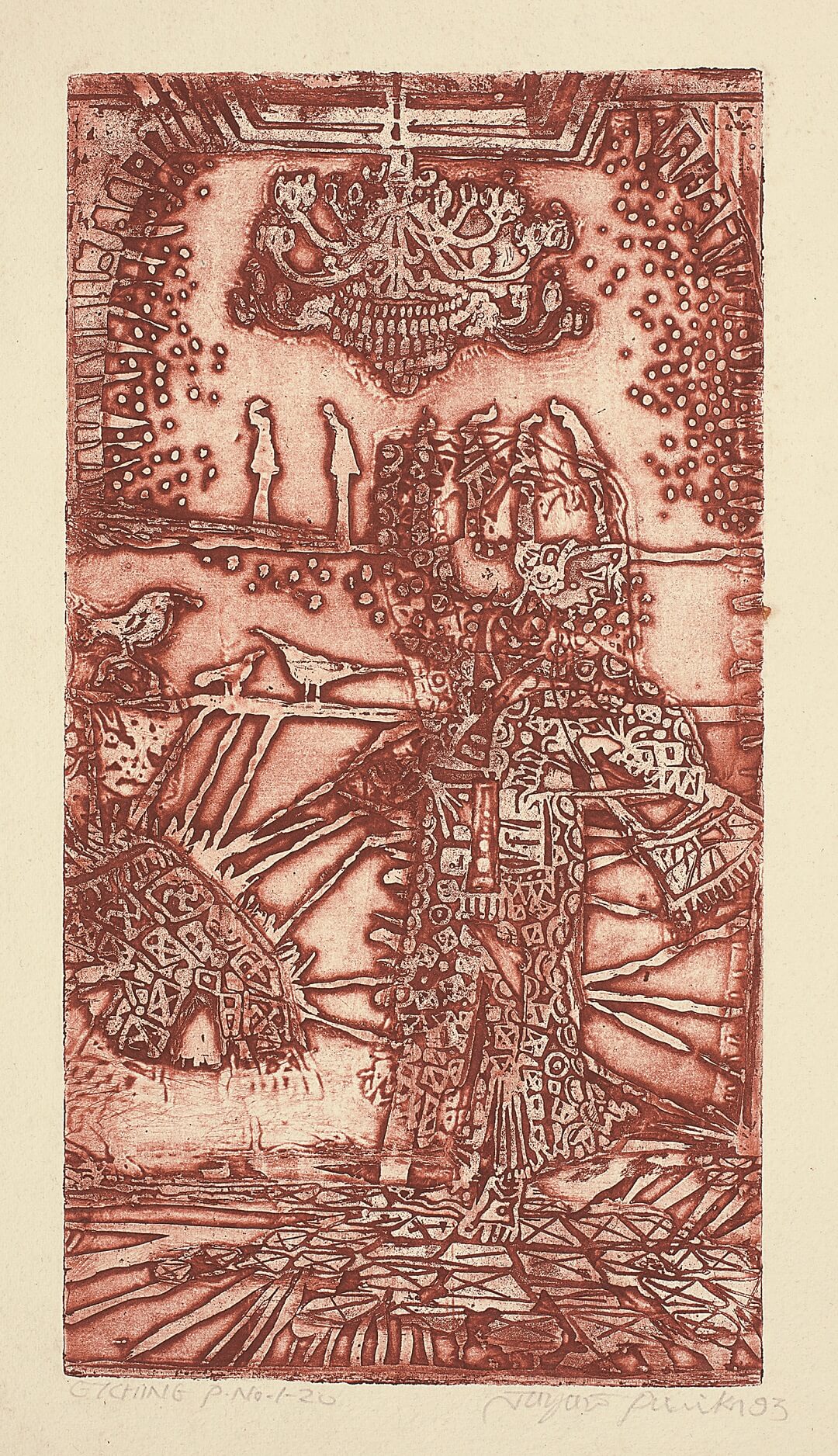

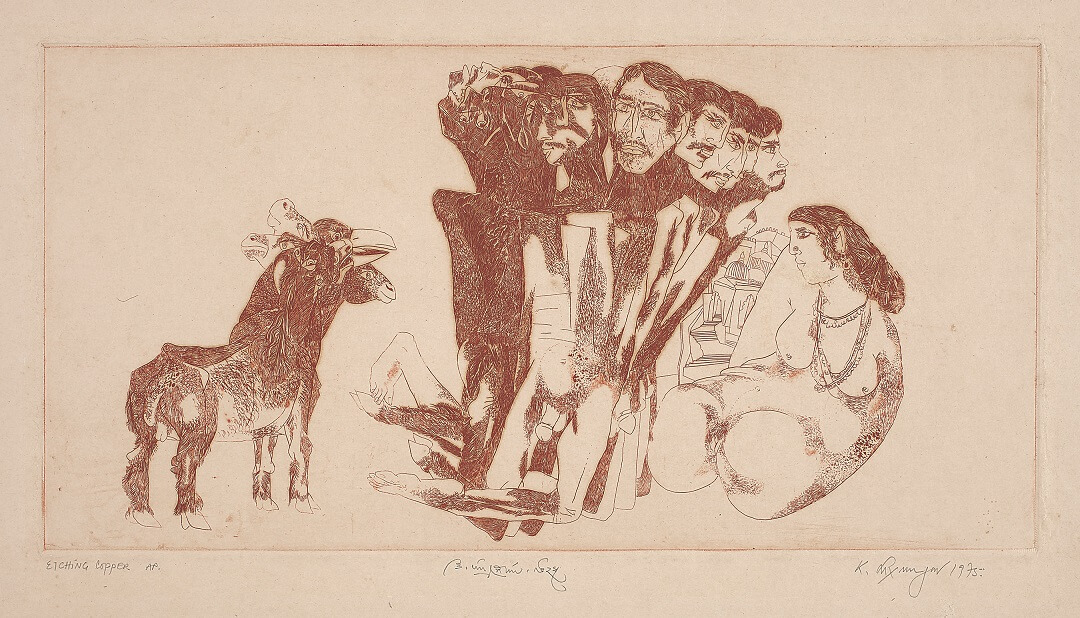

K. Laxma Goud

Untitled

Etching

D. L. N. Reddy

Untitled

Etching and aquatint

By 1970, P. Gauri Shanker, Devraj Dakoji, K. Laxma Goud and D. L. N. Reddy were practising printmaking in Hyderabad. The latter three had together set up a press in a garage in Hyderabad. Devraj consequently moved to New Delhi where, for many years, he headed the printmaking department at Garhi Studios. |

R. B. Bhaskaran

Echo of Freedom

R. B. Bhaskaran

Untitled

R. B. Palaniappan

Alien Planet X 3

Printmaking was introduced to the curriculum of the Government School of Arts and Crafts, Madras, in the 1960s. In the following decades, A. P. Paneer Selvam, R. B. Bhaskaran, and Dakshinamoorthy would become some of the most active and well-recognised printmakers in the city.

|

Older printmaking techniques—displaced by new technologies for the purposes of reproduction—continue to thrive in artists’ studios. The different processes of printmaking involve considerable physical labour and this material experience relentlessly pushes the artist-printmaker to reflect on the relationship between art and labour. As digital images saturate our lives and we live through a new technological revolution, this is the most opportune time to re-examine the life of the printed picture and the momentous technological and cultural revolution that this entailed. |

|

Ramendranath Chakravarty Untitled (Hempstead Heath) Etching and aquatint |

EXHIBITION VIEW'The exhaustive, informative and beautifully-mounted exhibition, The Printed Picture: Four Centuries of Indian Printmaking (September 9-19), curated by Paula Sengupta and held at the Harrington Street Arts Centre in collaboration with the Delhi Art Gallery, was truly representative of the diverse and innovative manner in which artists down the ages have expressed themselves through this medium.' 'Making History Come Alive,' The Telegraph, 28 September 2013 |

Presented by