The Present in the Modern: Remembering Gieve Patel

The Present in the Modern: Remembering Gieve Patel

The Present in the Modern: Remembering Gieve Patel

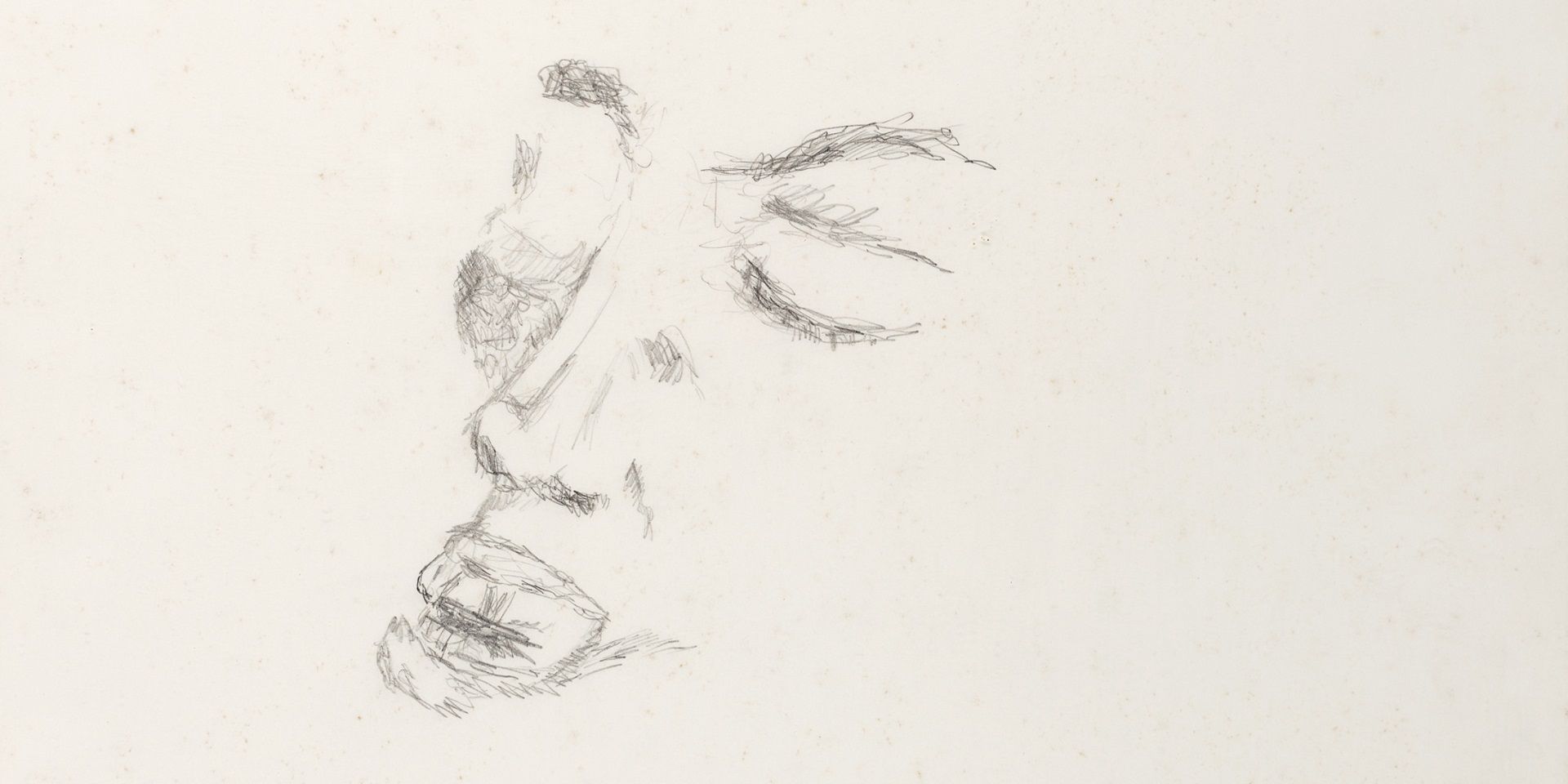

Gieve Patel, Actor, 2005, Graphite on paper, 43.7 X 38.1 cm. Collection: DAG

Gieve Patel (1940—2023) was a multifaceted Indian artist known for his contributions to the fields of art, poetry, and medicine. Born on September 18, 1940, in Mumbai, Patel's artistic journey was characterized by a unique blend of creativity and intellectual rigour.

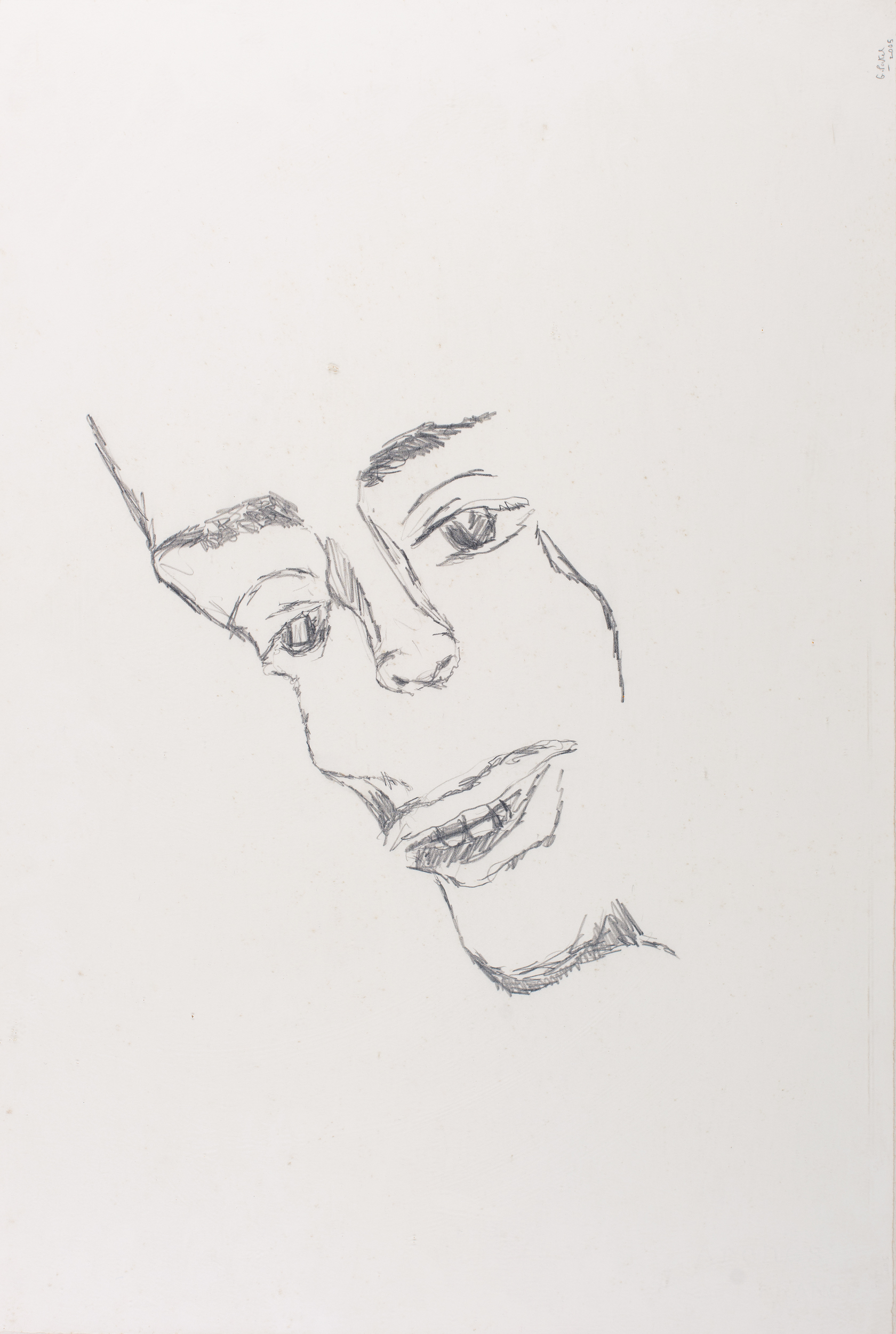

Patel was recognized for his paintings as well as sculptural work. His artistic style reflected a deep engagement with both figurative and abstract elements. His early works often featured realistic depictions of urban landscapes and human figures. Over time, his style evolved to incorporate more abstract and symbolic elements, showcasing a distinctive blend of form and content. He experimented with various mediums, including oil on canvas, watercolours, and sculpture. His paintings are characterized by bold strokes, vibrant colors, and a keen attention to detail. In his sculptures, Patel often explored the interplay of form and space, creating works that engaged the viewer on a sensory level. He also made several drawings and sketches throughout his career, to which he brought his medical training to bear—focusing on anatomical details and adding flights of fancy to frameworks of the normative human body. He studied medicine at Grant Medical College in Mumbai and worked as a medical practitioner. This unique combination of medical expertise and artistic talent has shaped Patel's perspective on the human body and its relationship to the broader human experience.

|

Gieve Patel, Actor, 2005, Graphite on paper, 55.9 X 38.1 cm. Collection: DAG |

As a writer, Patel frequently wrote about the state of Indian painting, confronting its problems honestly and critically, while also sharing his insights on the work of fellow artists. In the essay ‘To Pick up a Brush’ (2017), for instance, Patel writes about some of the challenges and discussions that have shaped contemporary painting in India, especially in a fast-evolving, and transforming, urban context. He writes, ‘Post-Independence India had no role for the urban, contemporary artist, the man who would fabricate and comment upon the present, and who would not necessarily continue with folk and classical forms. The world would certainly have been chill for him, with the unexpressed, ubiquitous question: ‘What is your work for? Who is it for?’ It has taken the artist two or three decades to reply simply: ‘It is for you. And me’. And specific third-world tragedies gave a special edge to the chill. In universal deprivation, may one allow oneself the luxury ‘to pick up a brush’?’ He was borrowing the titular phrase from a concern raised earlier by the artist Tyeb Mehta, who said, ‘To pick up a brush, to make a stroke on the canvas – I consider these acts of courage, in this country’.

|

Gieve Patel, Untitled, 1980, 45.7 X 37.3 cm. Collection: DAG |

Patel himself remained, over the course of his career, a consummate observer of the vagaries of urban living—from its challenges and problems to its delights and the scope it offered for creative intervention. In the essay, he also emphasises the significance of conversations among Indian painters, which have led to the birth and growth of contemporary painting in India. He describes the atmosphere of guarded fraternity in which these discussions take place, often publicly, and the uneasy, warring connection that binds painters from different centers across the country.

|

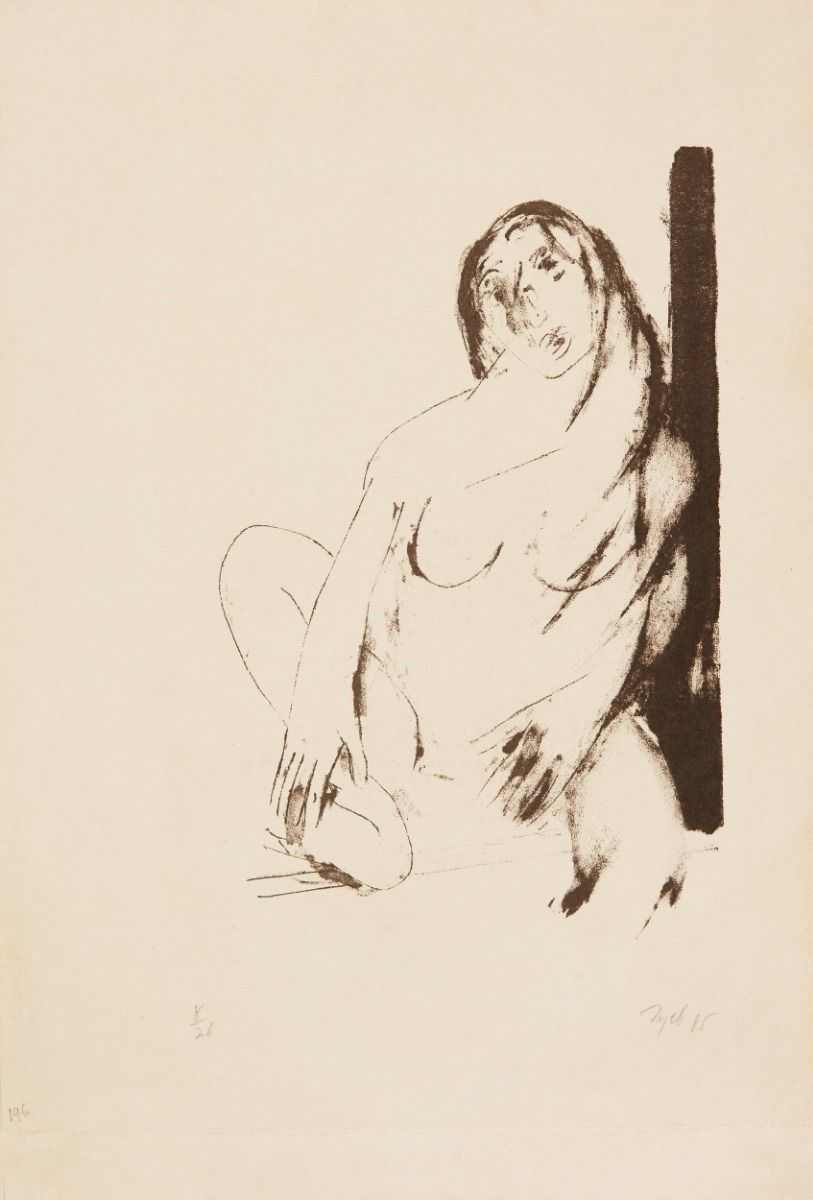

Tyeb Mehta, Untitled, 1985, Lithograph on paper, 33.5 x 21.6 cm. Collection: DAG |

He also noted the role of commercial galleries and public institutions that could aid the development of modern Indian painting: ‘The (modern art) scene is staged in a mere handful of commercial galleries that have worked valiantly against odds. But then there is also the Jehangir Art Gallery in Bombay, an utterly unique institution, a gallery rented out by the week where exhibitions of novices alternate with those of well-known painters, and both are impartially attended by crowds of a size only important museums attract in most countries. Calcutta too has comparable public galleries, frequented by large numbers of intelligent, enquiring people who most often are not buyers.’ He wished, therefore, for galleries and museums to open up access for the curious and center the relationship between art and the public over that of the artistic commodity and its consumer.

|

Akbar Padamsee, Untitled , 1965, Oil on canvas, 91.4 X 91.4 cm. Collection: DAG |

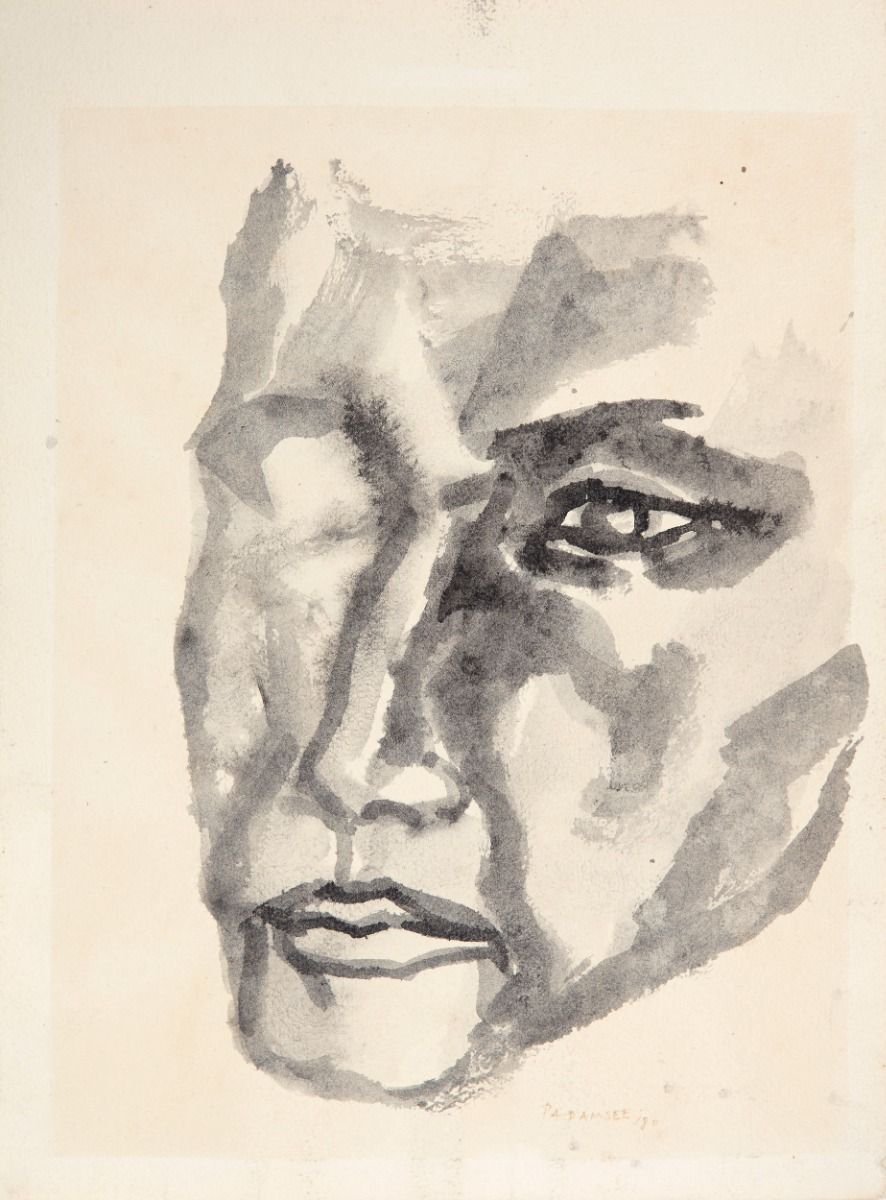

In the essay, Patel cites statements from artists like Tyeb Mehta and Sudhir Patwardhan, reflecting their internal questioning and the persistent theme of the human figure in Indian painting. He also discusses the influence of Western art, particularly the impact of Paul Klee on Indian artists, and the emphasis on means of working over subject matter by artists like Akbar Padamsee, Tyeb Mehta, and S. H. Raza. Furthermore, Patel addressed the responses of Western critics to Indian painting, highlighting the political motivations behind some Western perspectives. He also reflects on the impact of economic factors on Indian artists, expressing concerns about the potential loss of independence if the art market exerts greater influence in the future.

|

Akbar Padamsee, Untitled, 1980, Watercolour on handmade paper, 33.0 x 25.4 cm. Collection: DAG |

Elsewhere, in texts like ‘Contemporary Indian Painting’ (1989), he described his artistic process as a reflection of the underlying violence in society, of ‘human beings against animals, adults against children, men against women, the strong against the weak’. He expresses a sense of accountability to the place from where he operates, acknowledging the prevalence of violence not only in his own country but also in other nations. He draws a parallel between the need for nonviolence and the representation of victims in his artwork, emphasizing the importance of acknowledging and giving voice to those who have suffered. He also wrote about the transformative power of art, describing the pleasure in turning pain and wretchedness into a form of phantasmic play. He suggests that this transformation can provide a sense of control over these forces and alleviate fear, both for himself as the creator and potentially for the viewer. It is due to his close engagement with such problems that Gieve Patel will be remembered as one of the most sensitive practitioners of Indian modern art in the gallery of greats that forged the post-independent scenario.