People of Bengal: Coloured etchings by F. Baltazard Solvyns

People of Bengal: Coloured etchings by F. Baltazard Solvyns

People of Bengal: Coloured etchings by F. Baltazard Solvyns

|

People of Bengal: Coloured etchings by F. Baltazard Solvyns THE ALIPORE MUSEUM Kolkata, 25 April - 5 July 2025 DR. BHAU DAJI LAD MUMBAI CITY MUSEUM Mumbai, 27 April - 29 June 2024 Exhibition by DAG F. B. Solvyns Tcharok Poudjah (Carak Puja) Colour etching tinted with watercolour on paper |

|

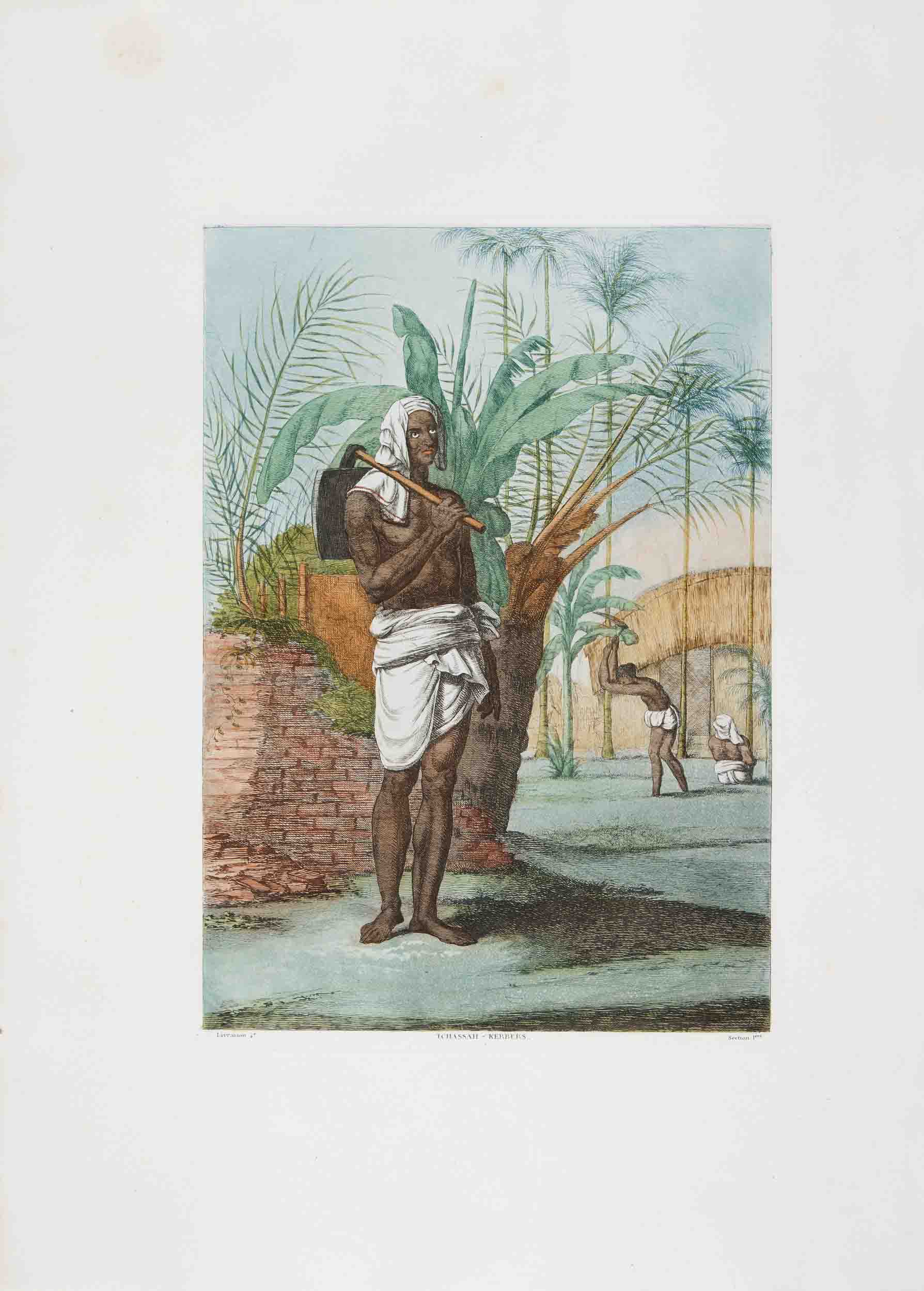

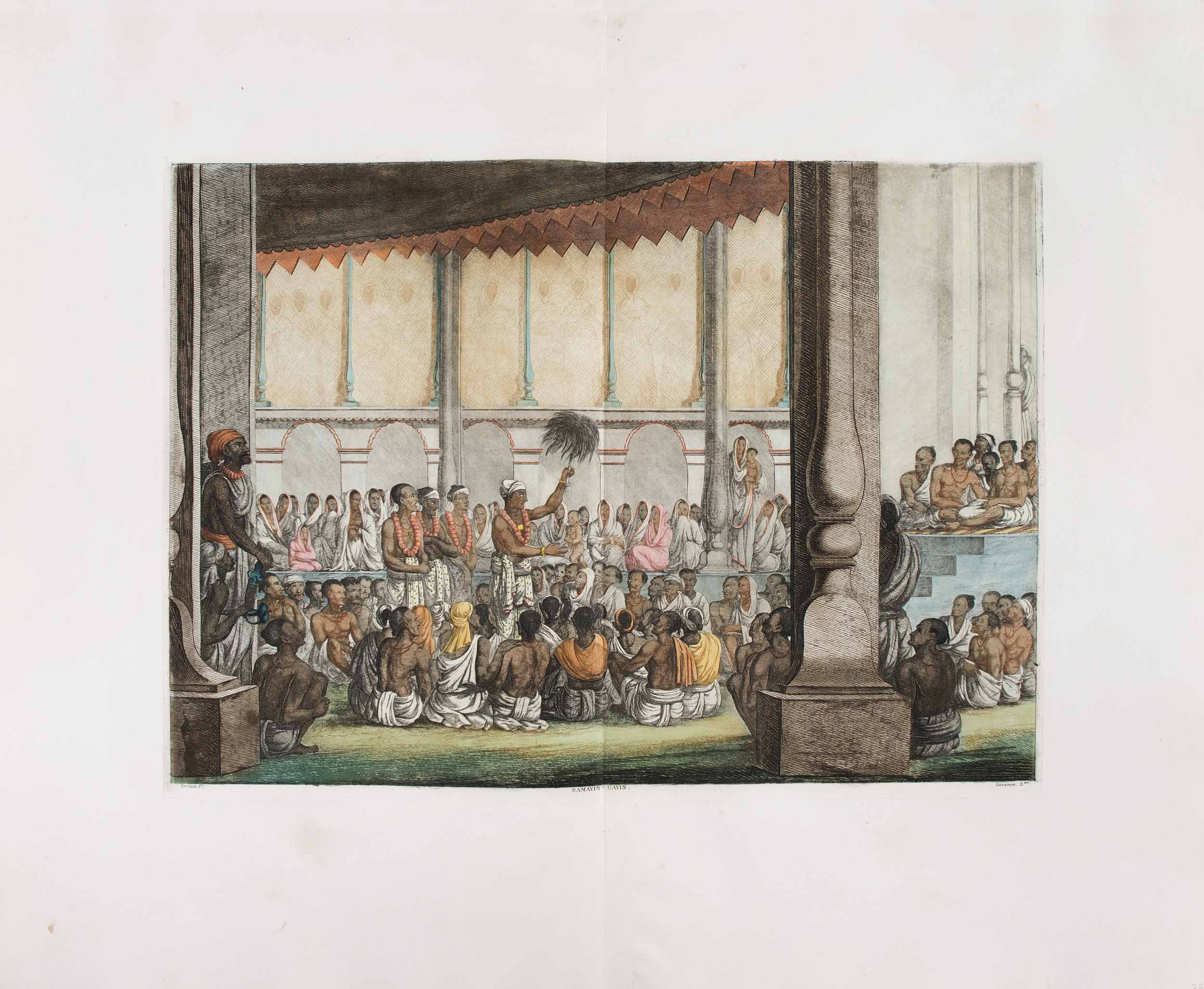

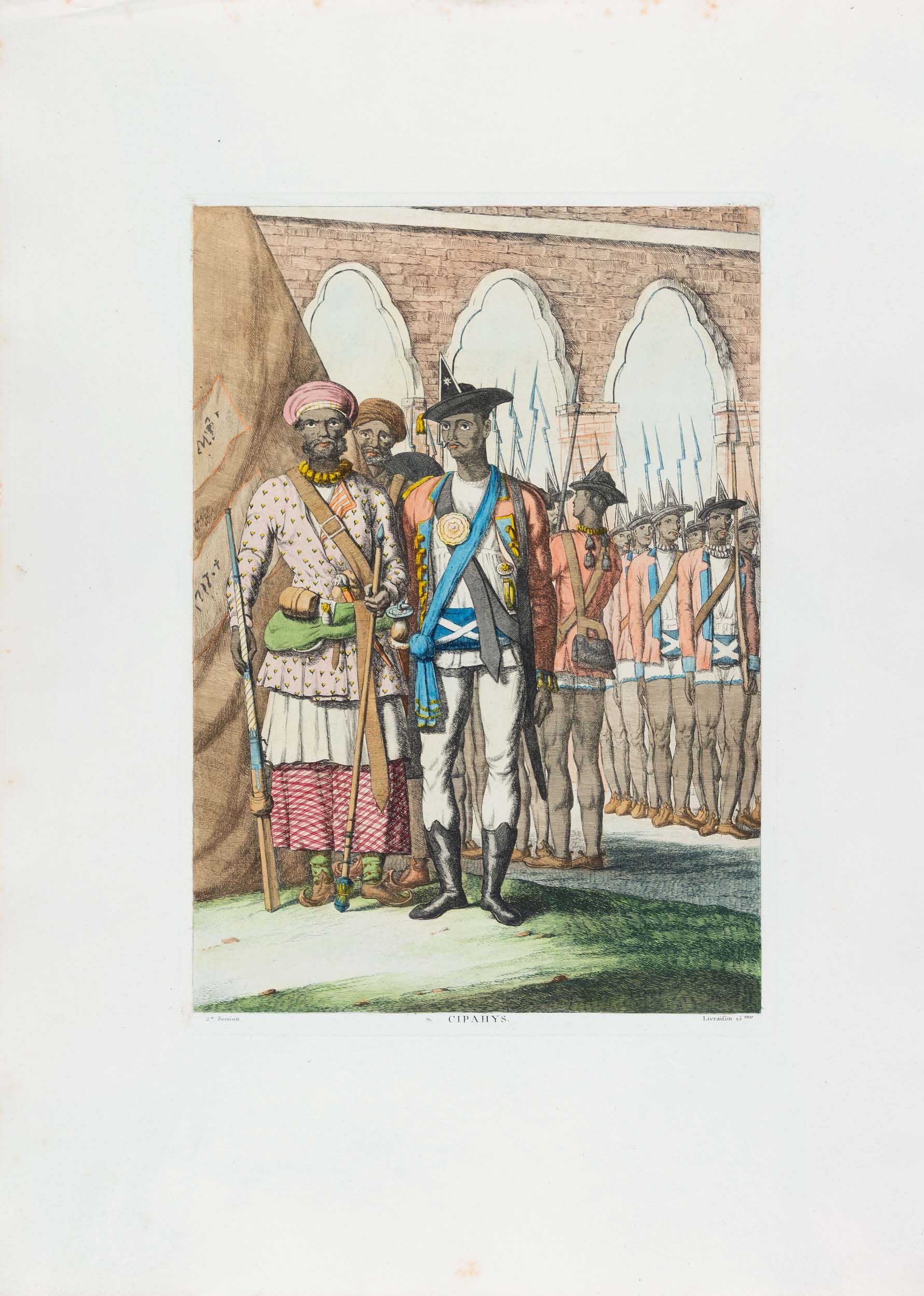

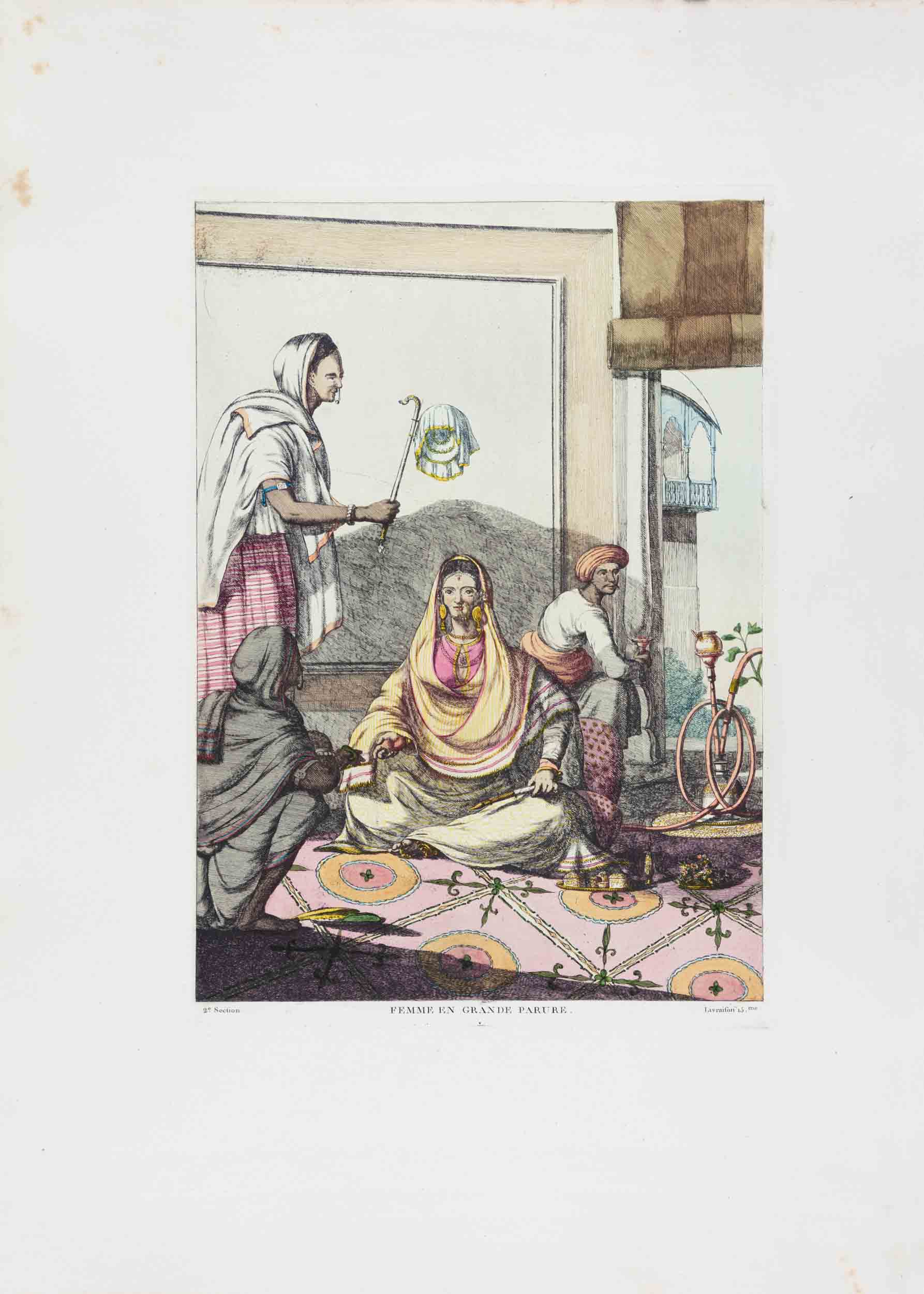

Four huge volumes, titled ‘Les Hindoûs’ (in English, ‘The Hindus’) contain a series of etchings made by François Baltazard Solvyns, presenting an encyclopaedic vision of the people and customs of eastern India at the end of the eighteenth century. The artist arrived in Calcutta in 1791 and lived there for over a decade. His great work focuses the people in Bengal and from neighbouring regions. Born and trained in Antwerp, Solvyns came to India in the hope of making his fortune. Working in Calcutta without permission from the board of the East India Company, he stayed on the margins of European society and engaged with all aspects of Indian life that teemed around him. While picking up odd jobs, he embarked on an ambitious project to produce a comprehensive survey of ‘the manners, customs, and dresses, of the Hindus’. The first edition, with 250 hand-coloured etchings, was published in Calcutta between 1796 and 1799. It was not commercially successful and Solvyns returned to Europe. Undaunted by his setback, in 1808-12 he published in Paris a second, enlarged edition, with bilingual descriptive text in French and English, and some additional plates, making a total of 288. The works exhibited here are taken from a complete set of the Paris version. |

|

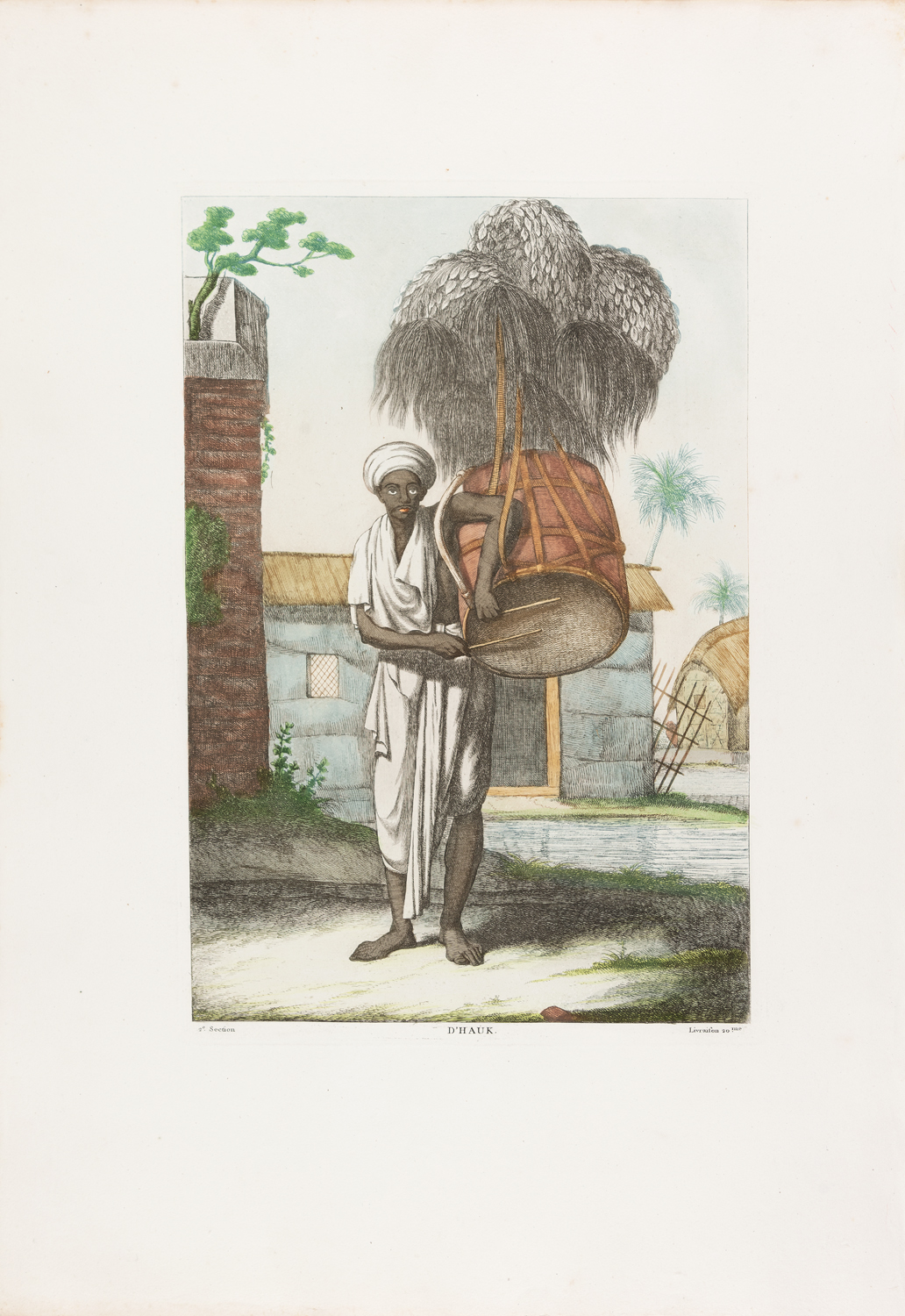

Baltazard Solvyns D'hauk (dhak) Colour etching tinted with watercolour on paper |

Baltazard Solvyns

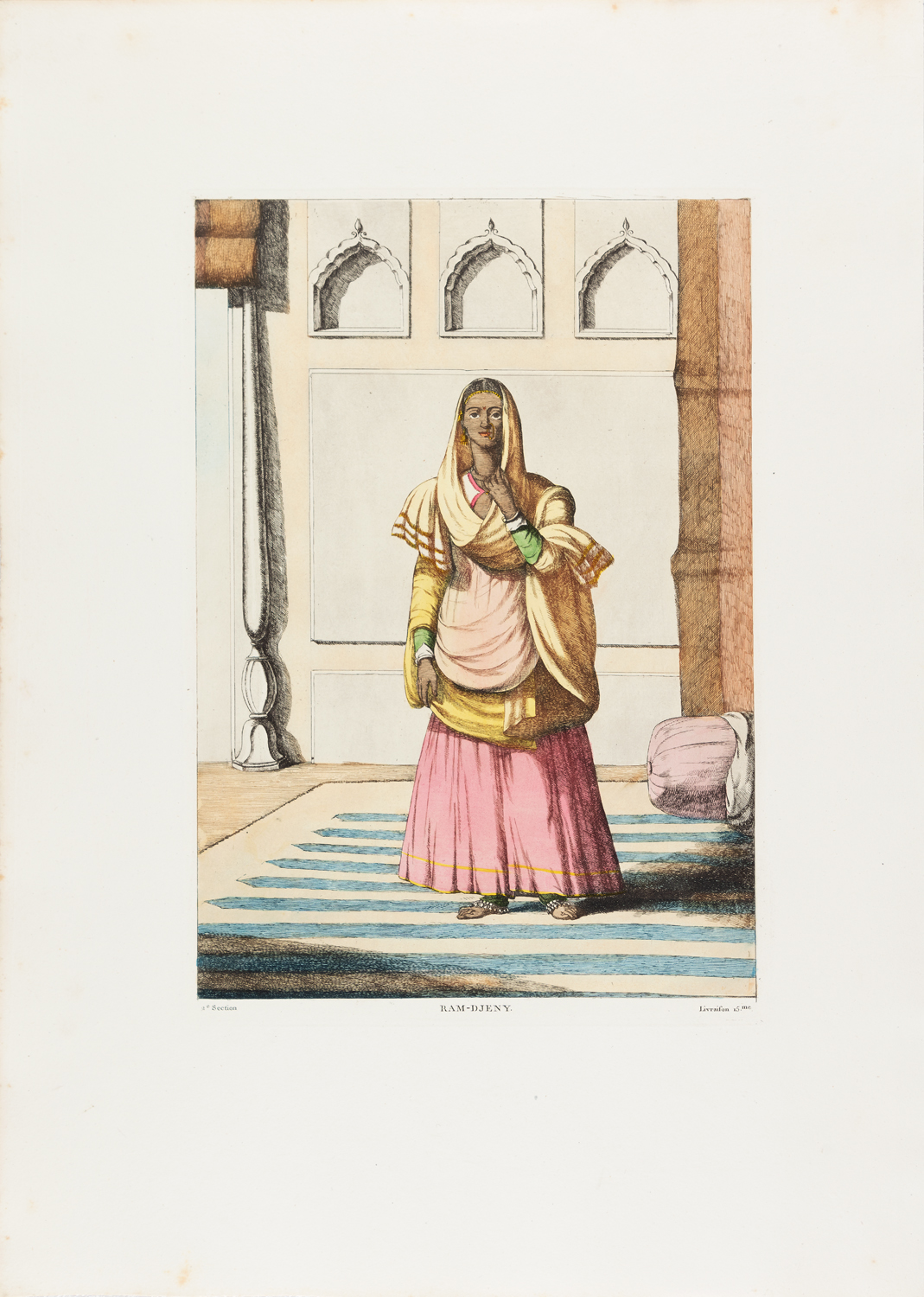

Ram-djeny (ramjanani)

Baltazard Solvyns

Porteurs de l'Ooriahs caste (Oriya bearers)

Baltazard Solvyns

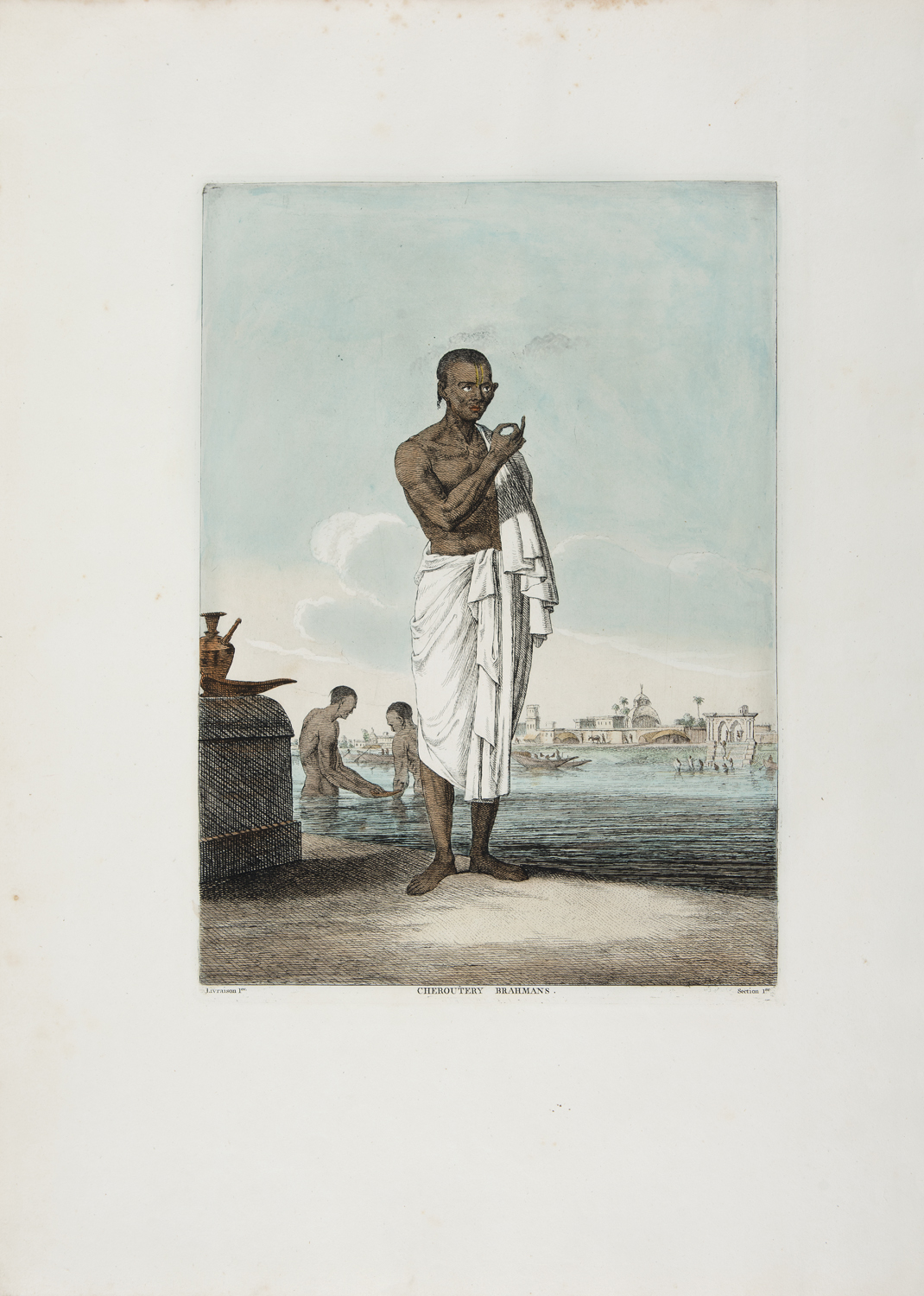

Cheroutery Brahmans (Srotriya brahmin)

|

Audiences at the time did not respond warmly even to this improved edition. They were accustomed to the picturesque landscapes of Thomas and William Daniell, a vision of Indian scenery and magnificent buildings that was easy to appreciate. By comparison, Solvyns focuses on ordinary people and his images are often sombre in mood. Modern audiences may see his work differently. It is an outsider’s view, for sure, and his interpretation is often problematic. But it is an extraordinarily detailed and intimate portrait of a people at a given moment in history. He includes representatives of every profession and every level of Indian society; he depicts festivals and sacred rites; and he shows us aspects of material culture, such as river boats and musical instruments that were then in common use. Every person and object is seen very closely, with an informed and inquisitive eye, and is shown, sometimes with wit, sometimes with a melancholy grandeur. Other artists who copied and plagiarised his images, made them simpler and more attractive, and they sold better than he did. Solvyns appeals to us today precisely because he was a challenging artist, who did not seek to delight us, but to confront us, to engage us in a discussion about the world he shared here for a while. Some of the titles given by Solvyns on the prints are puzzling as he tried to render Bengali words phonetically into French. In our captions we have used modern spellings, but we have also included those engraved on the plates, to help you identify them. |

|

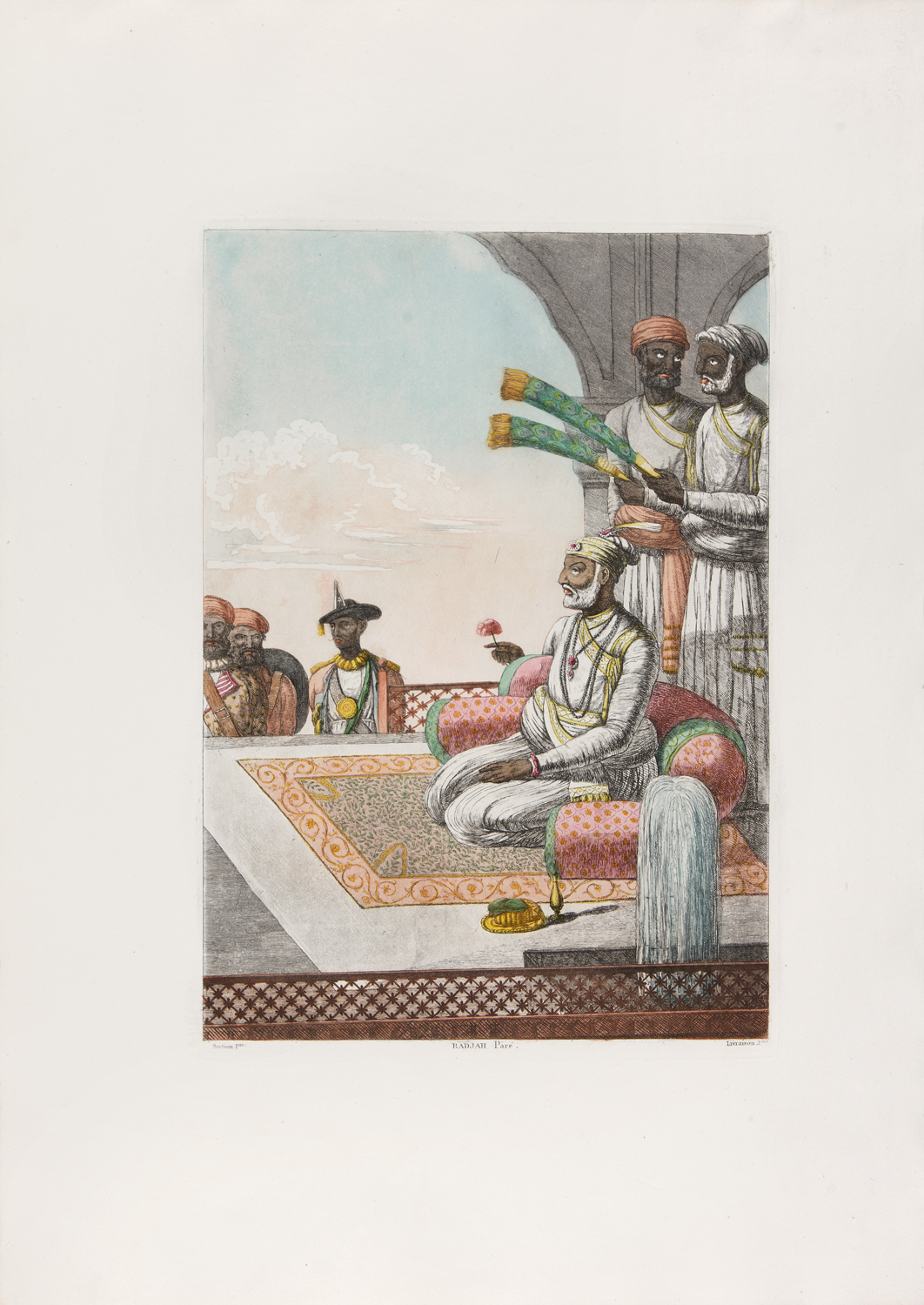

Baltazard Solvyns Radjah Paré (raja adorned) Colour etching tinted with watercolour on paper |

Baltazard Solvyns

D'hauk (Dhak)

Baltazard Solvyns

Radjah Paré (raja adorned)

Baltazard Solvyns

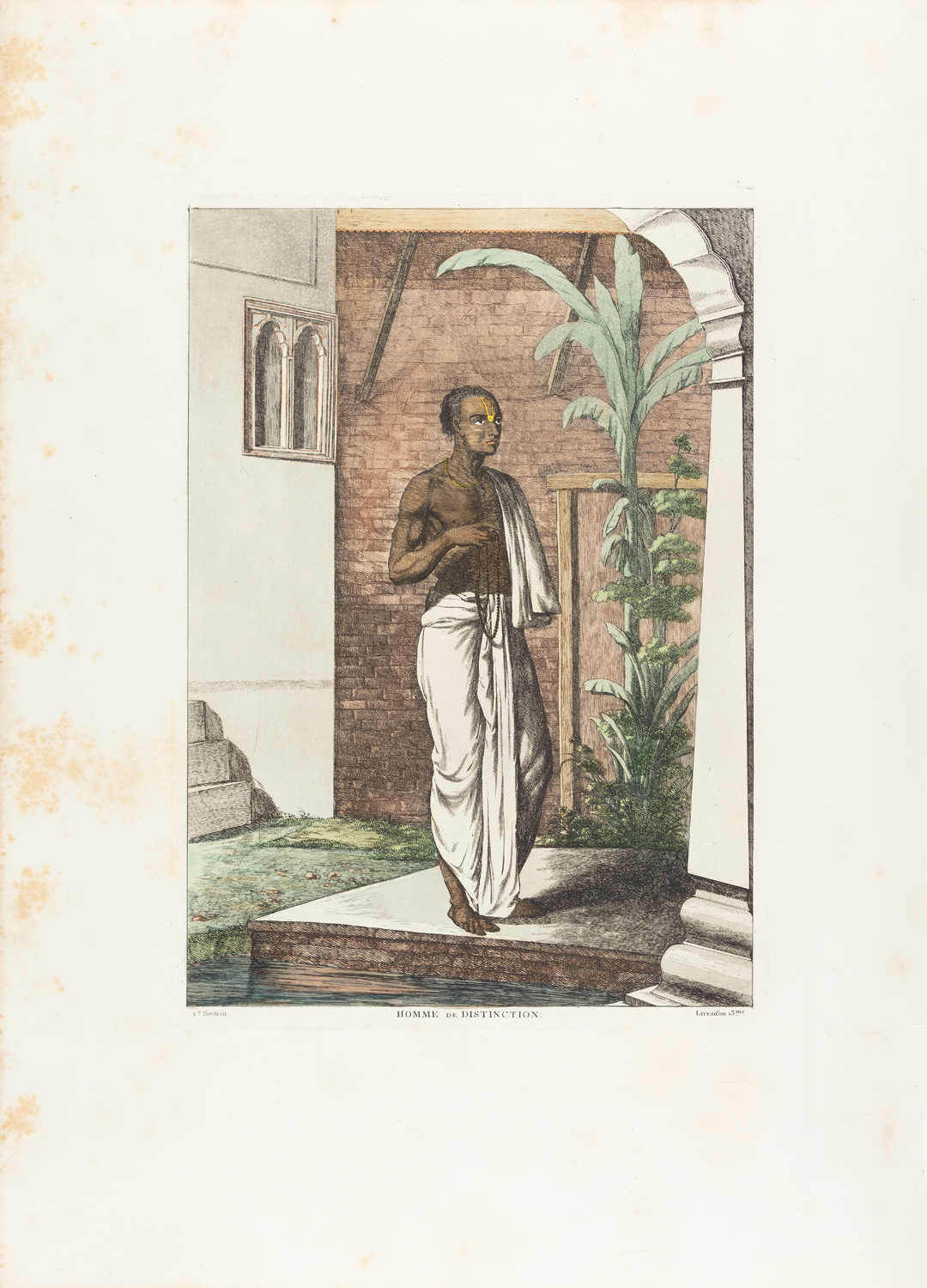

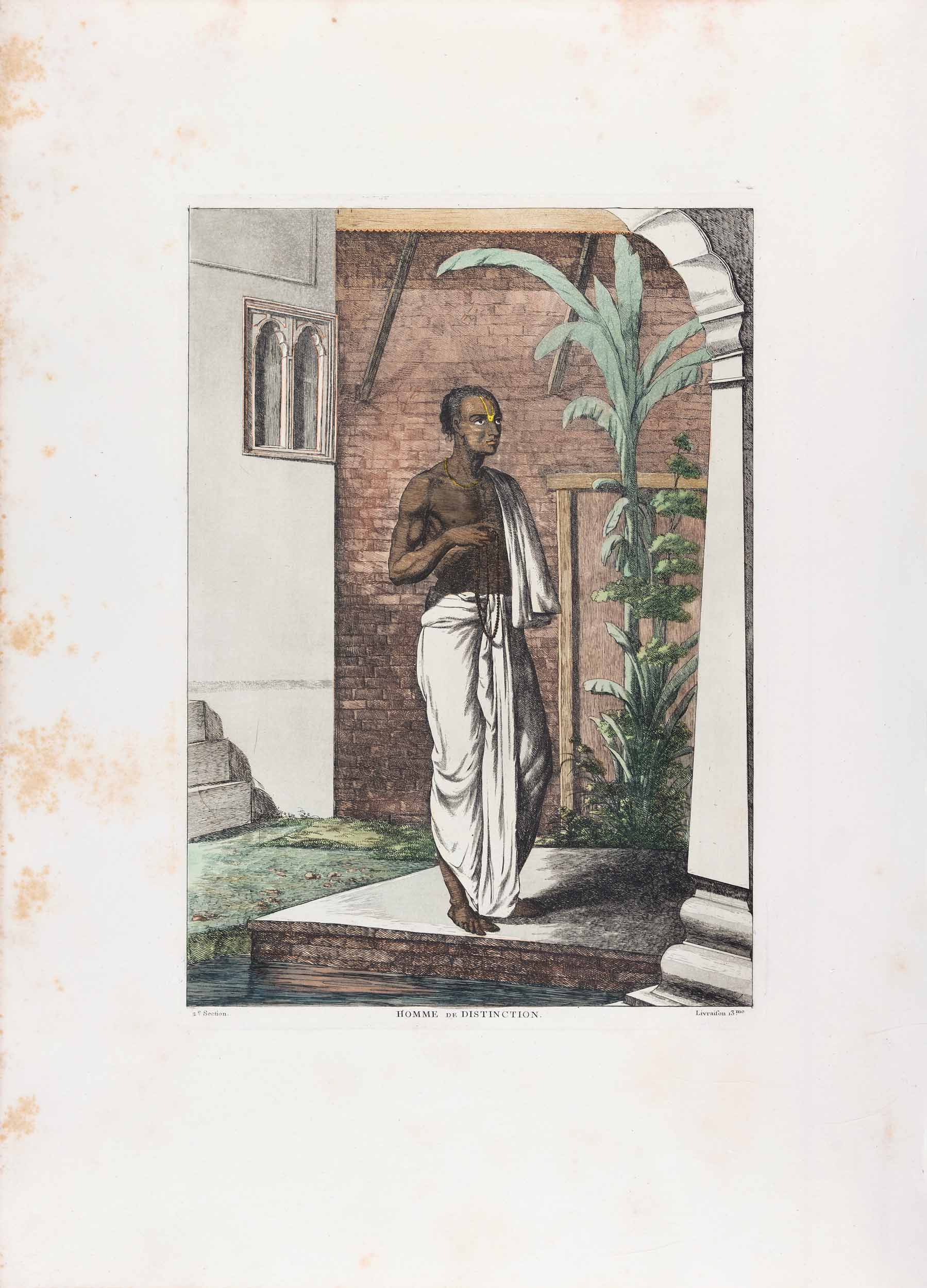

Homme de Destinction (man of distinction)

|

CASTES AND PROFESSIONS Given his notion that Hinduism is founded on the laws of Manu, we cannot be surprised that he opens his parade of Hindus with brahmins: he shows no fewer than five different kinds who he believes to be the best known types among the priestly caste, and who also appear to represent different regions, as they include Kanauji, Oriya and Brajbasi brahmins. Some of his captions, printed on the plates, can be puzzling, as Solvyns tries to transliterate for a French reading audience a name that he has heard spoken in Bengal. |

|

Baltazard Solvyns Colour etching tinted with watercolour on paper |

Baltazard Solvyns

Homme de Destinction (man of distinction)

Baltazard Solvyns

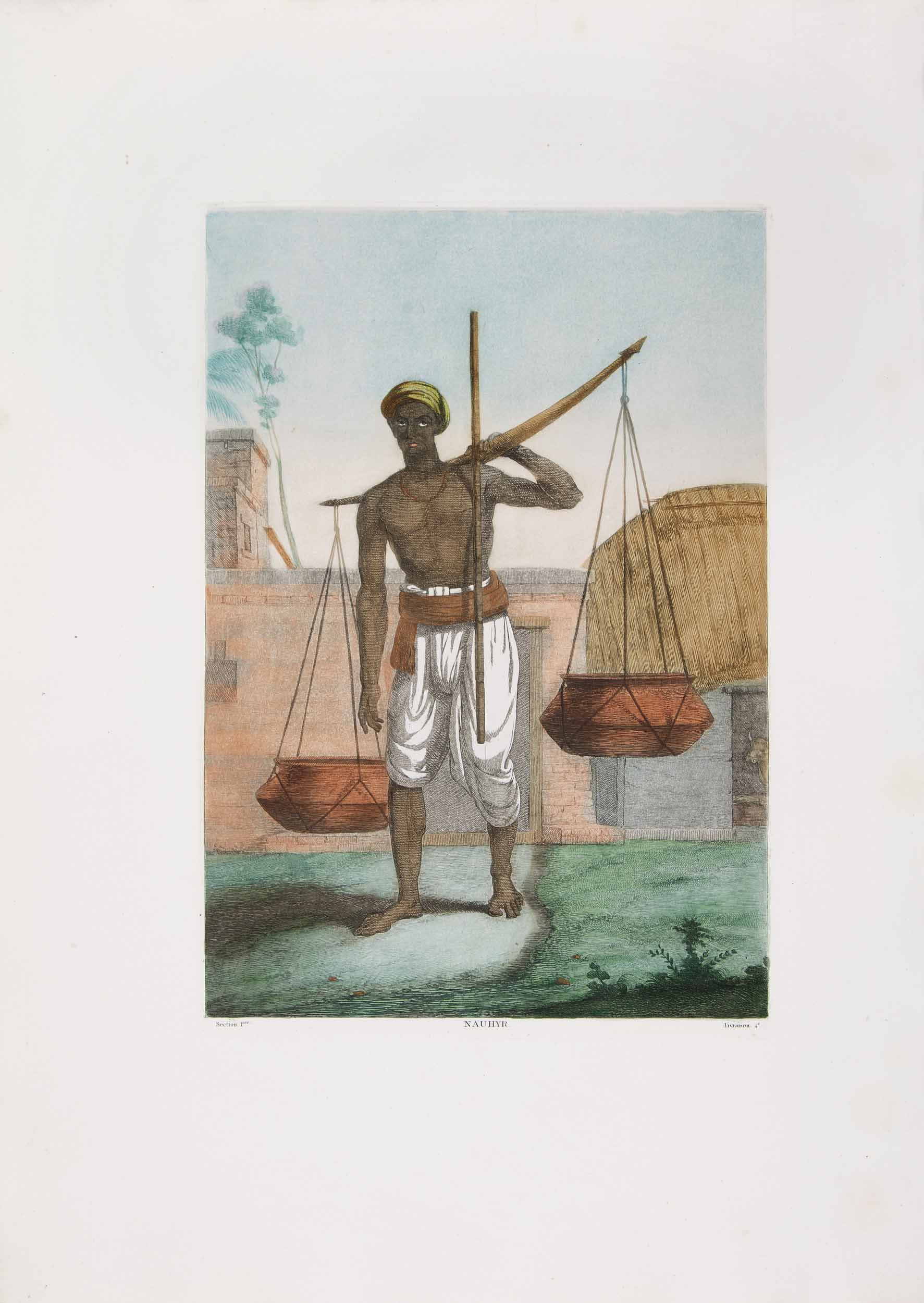

Nauhyr (ahir)

Baltazard Solvyns

Tchassa-kerbers (casa kaibarta)

|

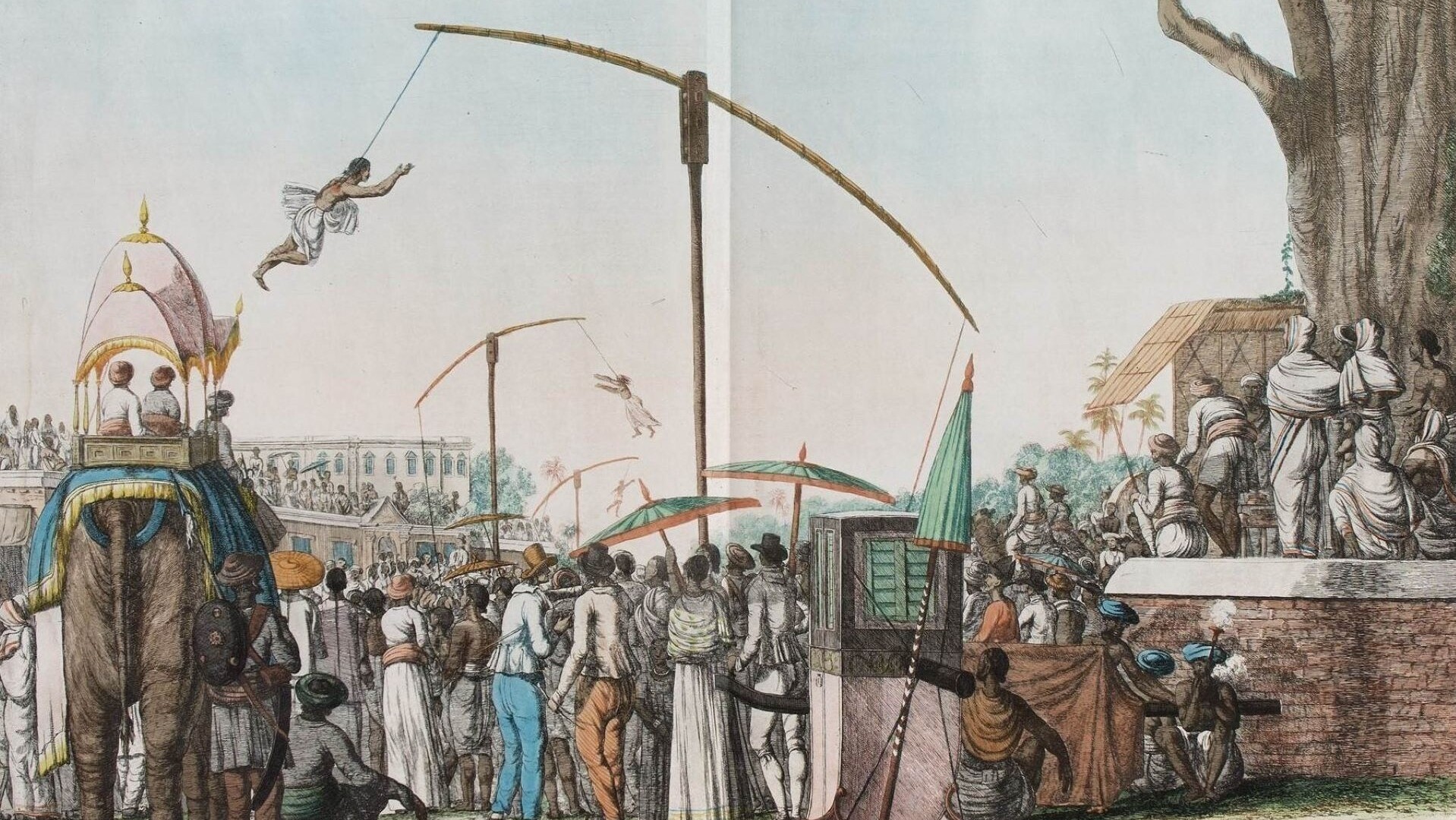

FESTIVALS AND CEREMONIES Europeans were enthralled by any elements of violence contained in Hindu rituals, especially when it was self-inflicted. Solvyns declares himself ‘astonished to behold their cruel expiations, their painful penances’ which seem so inconsistent with their otherwise ‘mild and humane manners’, and he can only conclude that the more ‘barbarous and sanguinary customs’ date from a very early period in their history. |

|

Baltazard Solvyns Raous Jatrah (ras yatra) Colour etching tinted with watercolour on paper |

Baltazard Solvyns

Routh Jatra (rath yatra)

Baltazard Solvyns

Mohabharat or Chobha (Mahabharat Sabha)

Baltazard Solvyns

Routh Jatra (rath yatra)

|

COSTUMES AND DRESS He now at last introduces some women. His comments on her dress at once reveal some of the assumptions that pervade his work: ‘The richness of this lady’s dress is striking, but the ornaments with which it is overloaded show that it is not an original costume of the Hindoo country, whose simplicity has in the course of this work been so often and so justly the subject of my praise. In reality the dress here represented is not worn by the Hindoos who conform strictly to the laws of Menu. It is that of public women, in the line of kept mistresses or concubines.’ So, as we have seen before, Solvyns’s imagined Hindu world is one of ‘original … simplicity’, governed by Manusmriti, from which any deviation indicates a degree of corruption. |

|

Baltazard Solvyns Natche (nautch) Colour etching tinted with watercolour on paper |

Baltazard Solvyns

Cipahys (sipahis)

Baltazard Solvyns

Balok (balak)

Baltazard Solvyns

Femme on grande parure (woman in full dress)

|

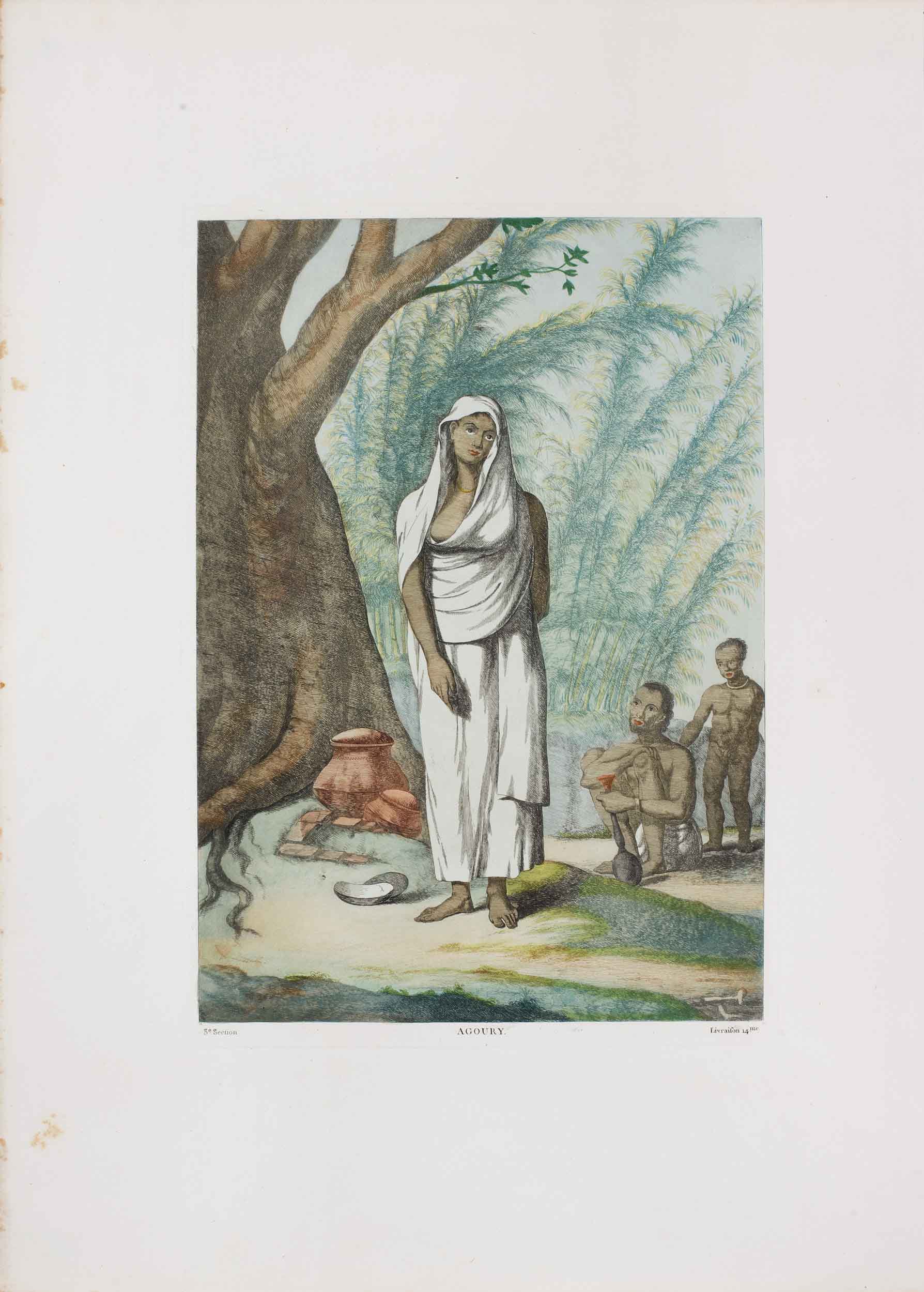

RENOUNCERS Solvyns records being assured by learned pandits that there were none at all, but he claimed to have met several and found it ‘extraordinary that the existence of these women should be so little known.’ He was perhaps a bit confused: he describes the aghori as a widow who has chosen ostracism rather than any of the other options available to her; and while he states correctly that she drank only from a skull, he portrays her as melancholic rather than shocking. |

|

Baltazard Solvyns Oudoubahus (udbahus) Colour etching tinted with watercolour on paper |

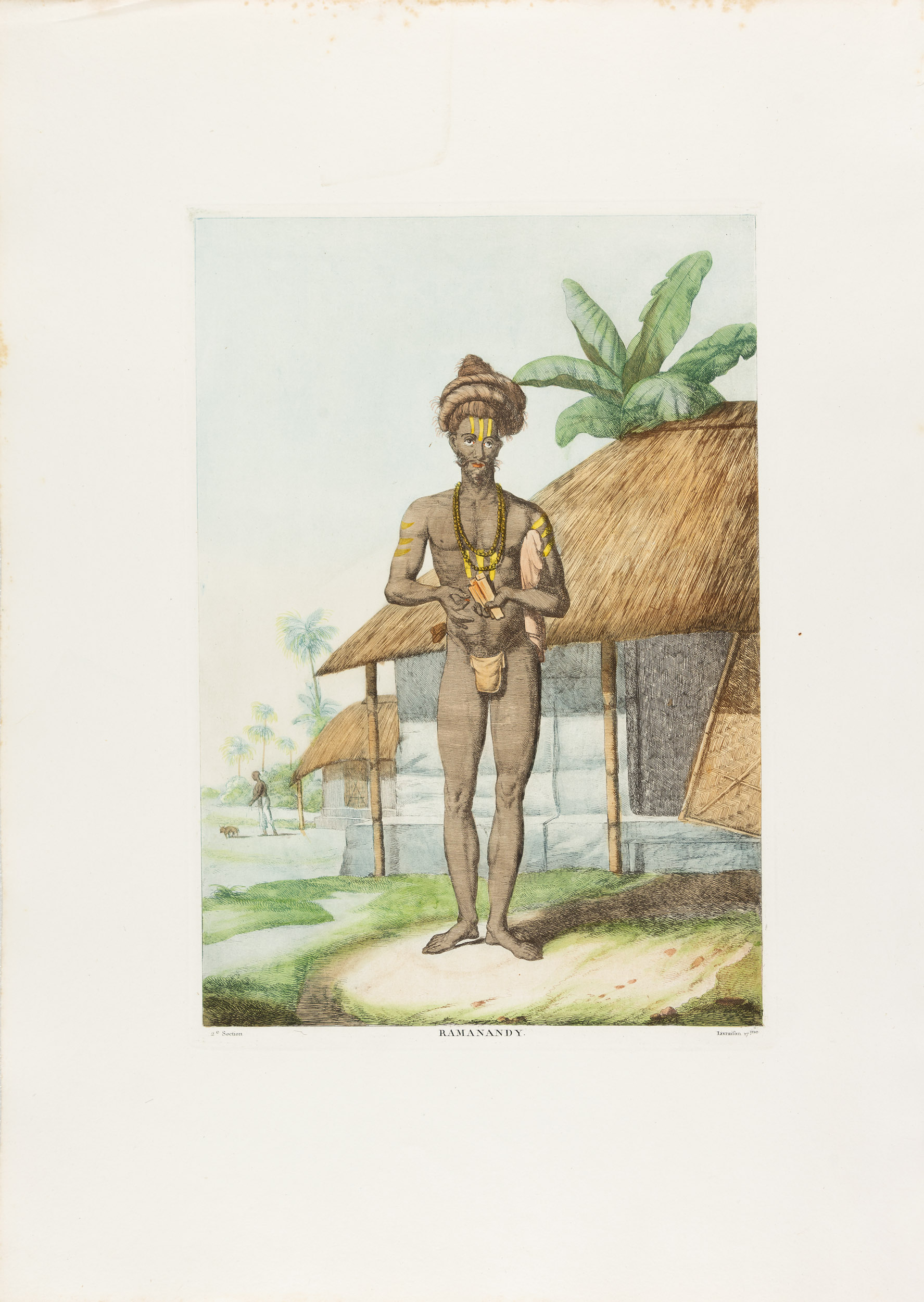

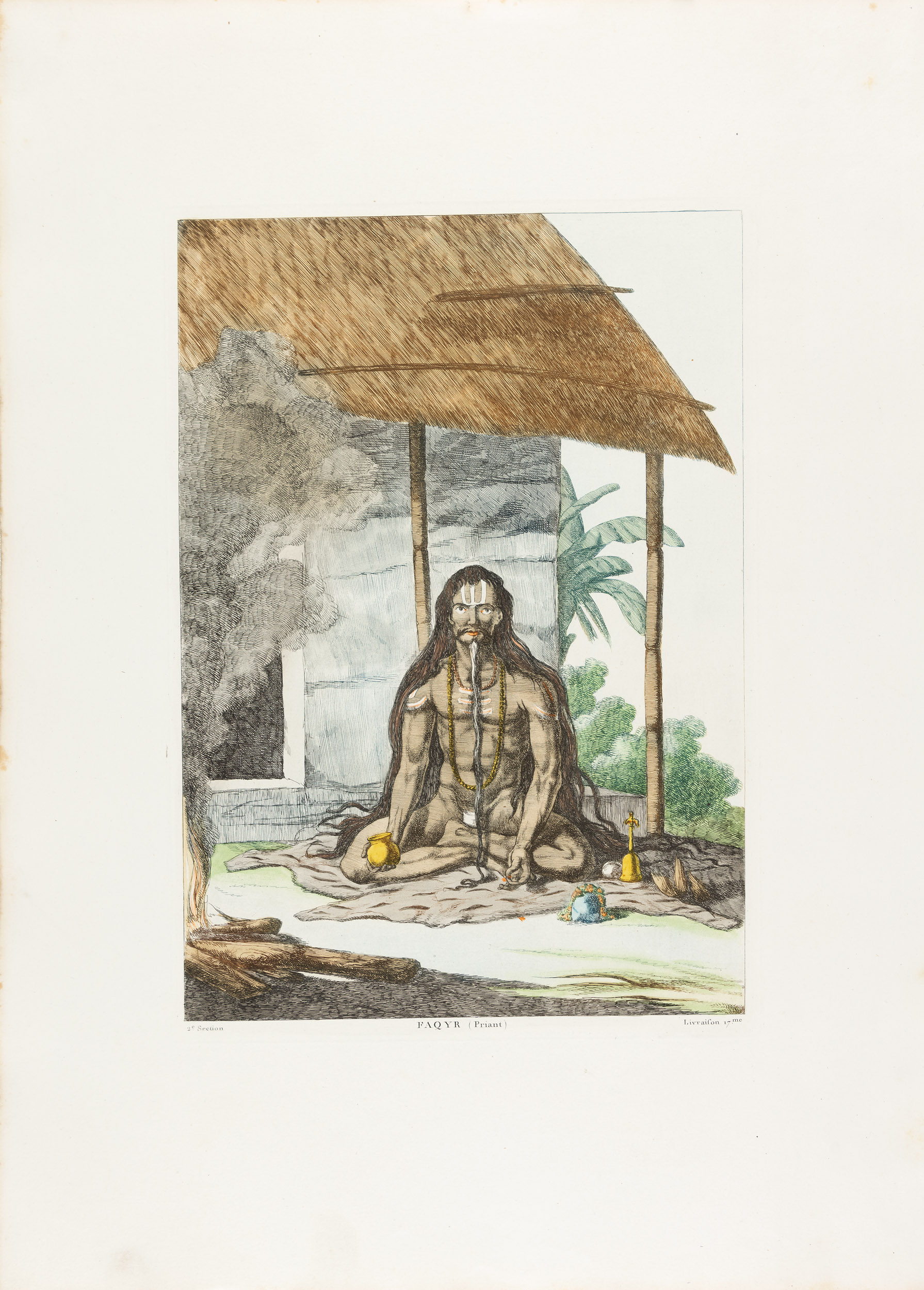

Baltazard Solvyns

Agoury (aghori)

Baltazard Solvyns

Ramanandy (ramanandi)

Baltazard Solvyns

Faqyr (priant) [fakir at prayer]

Baltazard Solvyns

Thobla (tabla)

Colour etching tinted with watercolour on paper

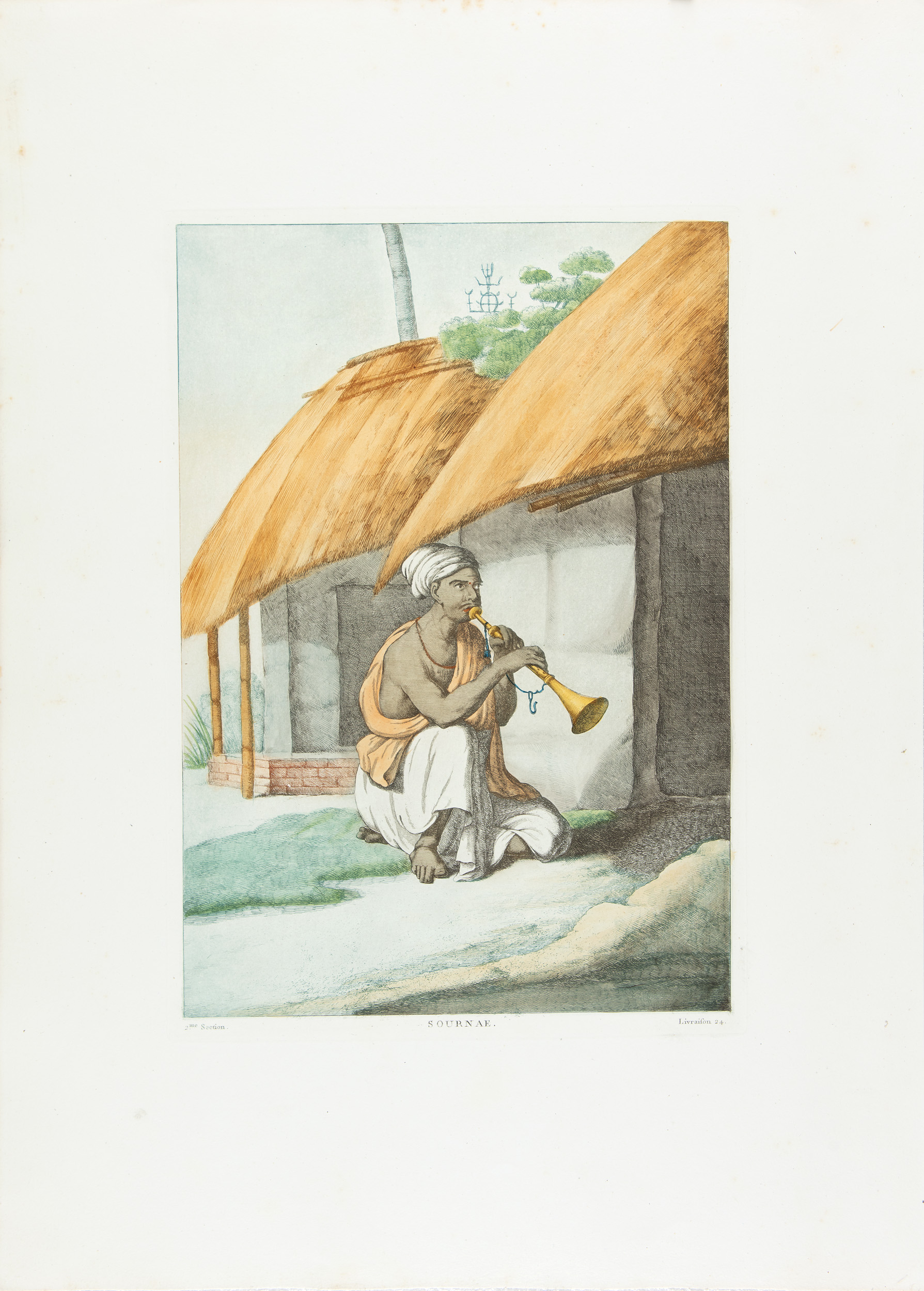

Baltazard Solvyns

Sournae (surnai, double reed oboe)

Colour etching tinted with watercolour on paper

|

|

'Barring a couple of etchings that showcase Europeans, Muslim couple and royals, the rest firmly focus on various aspects of the Hindu community in Bengal — castes and professions, festivals and ceremonies, costume and dress, renouncers, material culture, household servants and the natural world. They are realistic depictions of people and their daily lives. From a Mahabharat sabha to a rath yatra, a view of Kalighat temple, a khela dinghy — a pleasure boat used by Indians, musical instruments like jal tarang, Ramasinga (serpent horn), a bazaar scene, a sati procession, ascetics, nautch performance and representations of various castes and professions, there is so much to relish, understand and contemplate.' 'Baltazard Solvyns cast his artistic gaze on the ordinary people of Bengal', The Hindu, 11 August, 2023 'At first glance, it is an outsider’s view of Indians, or specifically Bengalis, and Indian audiences are now known to be a little wary of such representations. But curator Giles Tillotson argues that Solvyns was “revolutionary for his time”.' 'Through the eyes of a painter: Baltzard Solvyns, the artist who presented ordinary Indians to European audiences', The Indian Express, 17 August, 2021 |

Presented by