The Master and his student: A. Ramachandran on Ramkinkar BaijThe Editorial Team April 01, 2024 Even as we champion the modernist movement for its ability to disrupt the ways in which tradition hardens into convention, and reinvigorate the manner in which art relates to the social imagination of a people, community and nation, it is worth accounting for the ways in which student and teacher relationships have guided these modes of disruption. Indian modernism can be mapped as a series of exchanges between masters and their pupils, aided by the flowering of academic institutions of art outside the model of colonial pedagogy championed at Calcutta or Bombay. In Santiniketan, for instance, the artist A. Ramachandran lived for about seven years (from the late 1950s to the early 1960s) and learned several lessons from Ramkinkar Baij, the master sculptor and painter who taught at the Kala Bhavana. How does he remember this encounter and what influence did it have on Ramachandran’s own imagination? |

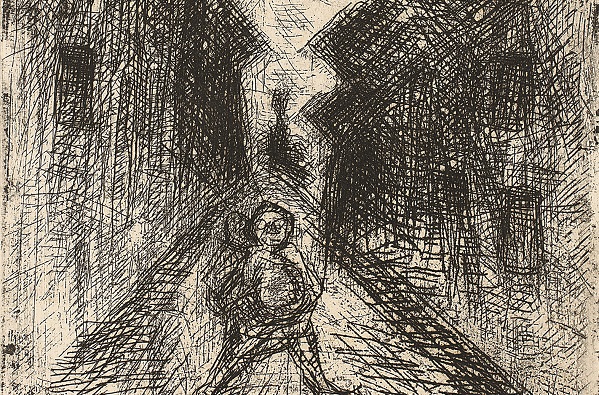

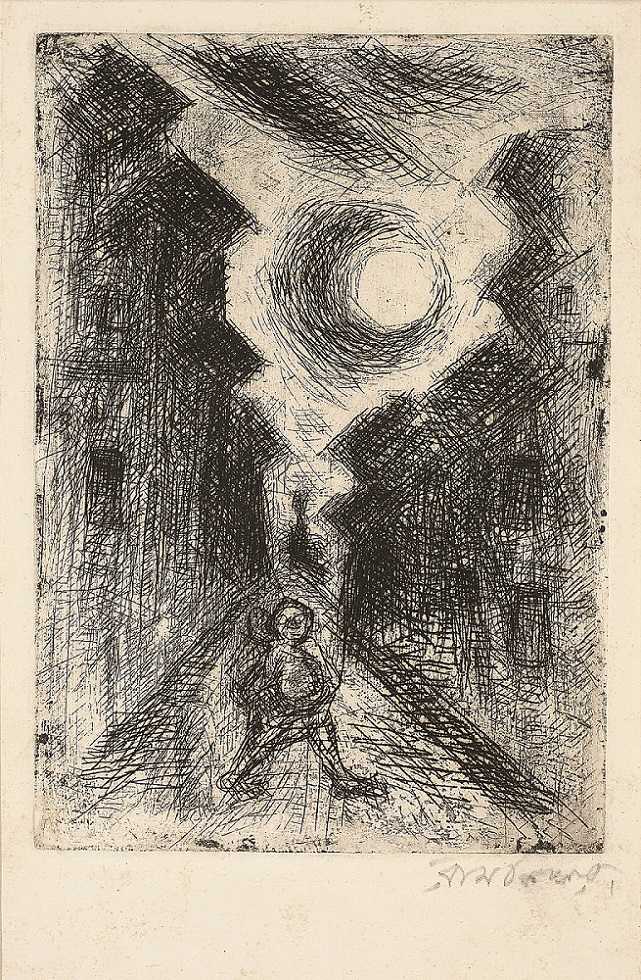

Ramkinkar Baij

Untitled

Etching on paper, 7.2 x 5.2 in.

Collection: DAG

|

Ramachandran, who was a graduate in Malayalam literature and a prolific writer of note as well, reminisces about this relationship in his book Ramkinkar: The Man and the Artist. It presents a poignant relationship between the two while giving us an insider’s look into the world of Santiniketan as perceived by two great modernists from across two generations. |

|

|

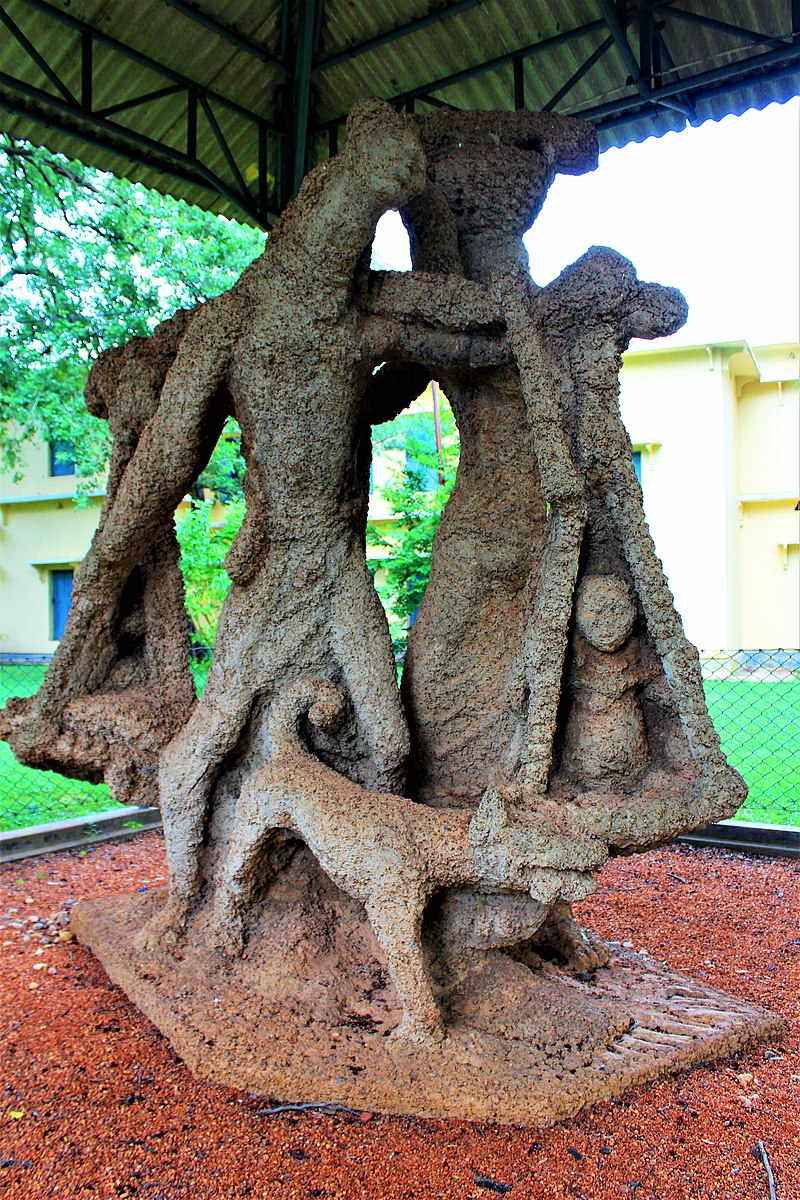

Ramkinkar Baij

Santhal Family

Image Courtesy: Wikimedia Commons

The Upside Down ArtistNot having known much about the great artist before reaching Santiniketan, Ramachandran had only seen a reproduction of Ramkinkar’s iconic sculpture Santal Family in an album of photographs. ‘A shiver ran through my body as if I was struck by a lightning when I looked at it,’ he writes. This piqued his curiosity and after joining Kala Bhavan in 1957 he would look for occasions to attract Ramkinkar’s attention, aspiring to become his pupil. This took a while, since the master had become a somewhat isolated figure—although still respected widely in Santiniketan—and most of his famous works had already been made. Eventually, as he met Ramachandran, he proceeded to symbolically turn the artist upside down, initiating a fresh departure that was as revelatory as comic. |

Ramkinkar Baij

Image Courtesy: Wikimedia Commons

‘Looking back, I realise how difficult Kinkarda was, as a teacher. Teaching every student was not his habit since he knew that his methodology was not easy to follow. For one whole year he avoided teaching me even though he liked me because of my ability to act and sing. He started listening to my singing long before he cared to teach me. For the function to introduce freshers, he created an event of illusion with me. He made me wear a shirt in place of a pant and a pair of pants in place of a shirt holding shoes in my hands. He made paper cutouts of palms and stuck them on my feet. Then he covered a football with a wig and tied it on my waist. With such a simple innovative way, he created the illusion of my walking on my hands upside down.’ |

|

|

Ramkinkar Baij

Collection: DAG

The ProcessRamachandran’s text provides many instances of Ramkinkar at work. The younger artist observes the master at work surreptitiously to begin with, discovering the strange world of a personal atelier that resembled a natural hunting ground. ‘Kinkarda was a self-taught sculptor. He learnt by the trial and error method trying to solve his problems with whatever materials available. Clay was his elementary medium and he used cement and pebble mixture as stated earlier, for his outdoor monumental sculptures. Kinkarda used to take classes in the morning and in the afternoon he would start his own work and remain totally engrossed in his creativity till late at night. |

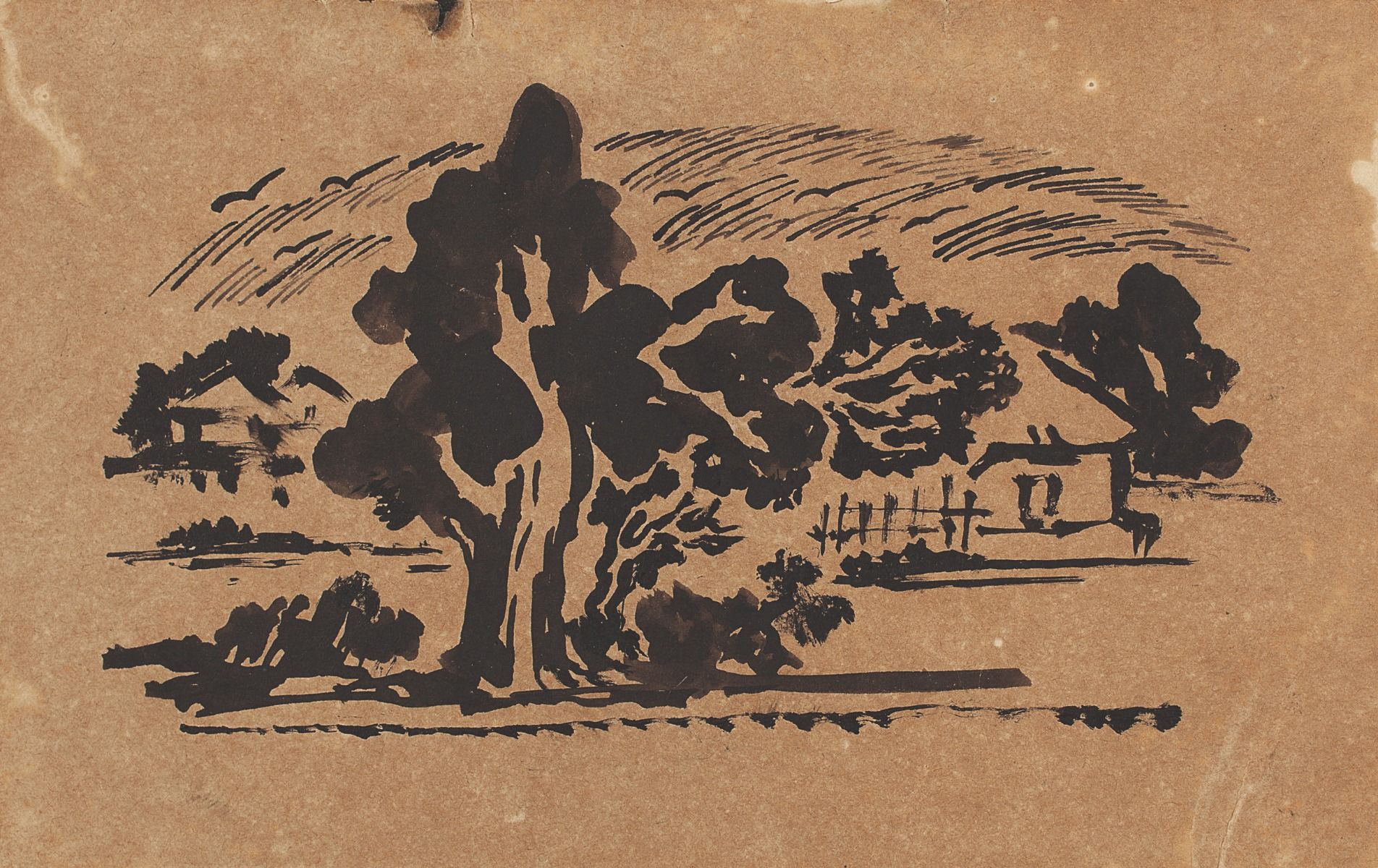

Ramkinkar Baij

Untitled

1943, Water colour and ink on paper, 6.7 x 9.5 in.

Collection: DAG

‘Occasionally, I used to peep through the window and, almost like a thief, observe him working. Kinkarda working on a sculpture was quite spectacular. First, he would throw large chunks of clay on a sturdy armature. Next he would start attacking the mass of clay like a wild animal, attacking its prey. Merciless slashes with a long modeling knife would gradually carve out the intended form. He would go around and look at the shape from every angle, like the animal assessing its prey before the next round of attacks. He would go on adding clay and slashing away the redundant till he got the correct form. For finishing, he would use both his hands with their claw-like nails, literally clawing the sculpture into its final form. From time to time he would fill his mouth with water to spray on the sculpture, an unconventional way of keeping it wet.’ |

|

|

Ramkinkar Baij

The Poet (Head of Rabindranath Tagore)

1938, Cement, 22.0 X 11.2 X 11.0 in.

Collection: DAG

Ramkinkar Baij

Mill Call

Image courtesy: Wikimedia Commons

The Master’s EyeRamkinkar’s modernism was inflected by his blending of a traditional crafts practice with a personal instinct that critiqued the typical subject matter of artisanal ‘craftwork’ (from myths and legends towards individuals and socially marginalised communities), while remaining true to the textures and potential of cheap, widely available materials. Ramachandran emphasised the qualities for which his talent was noticed by master pedagogues like Nandalal Bose. |

Ramkinkar Baij

Untitled

Watercolour and ink on paper, 7.5 X 9.5 in.

Collection: DAG

‘Kinkarda was initiated into modeling by the village idol makers at a very young age. Because of his extraordinary gift in painting and modeling, he soon became an asset for them. Kinkarda himself had narrated to me how this service was always sought to paint the eye of Durga, an act reserved for the master craftsman. No wonder when Master Mashai (Nandalal Bose) first saw his works, he commented that Kinkarda was already a ‘tempered bamboo’, a Bengali expression for matured proficiency.’ |

|

|

Ramkinkar Baij

Collection: DAG

Ramkinkar Baij

Untitled

1961, 10.5 x 14.5 in.

Collection: DAG

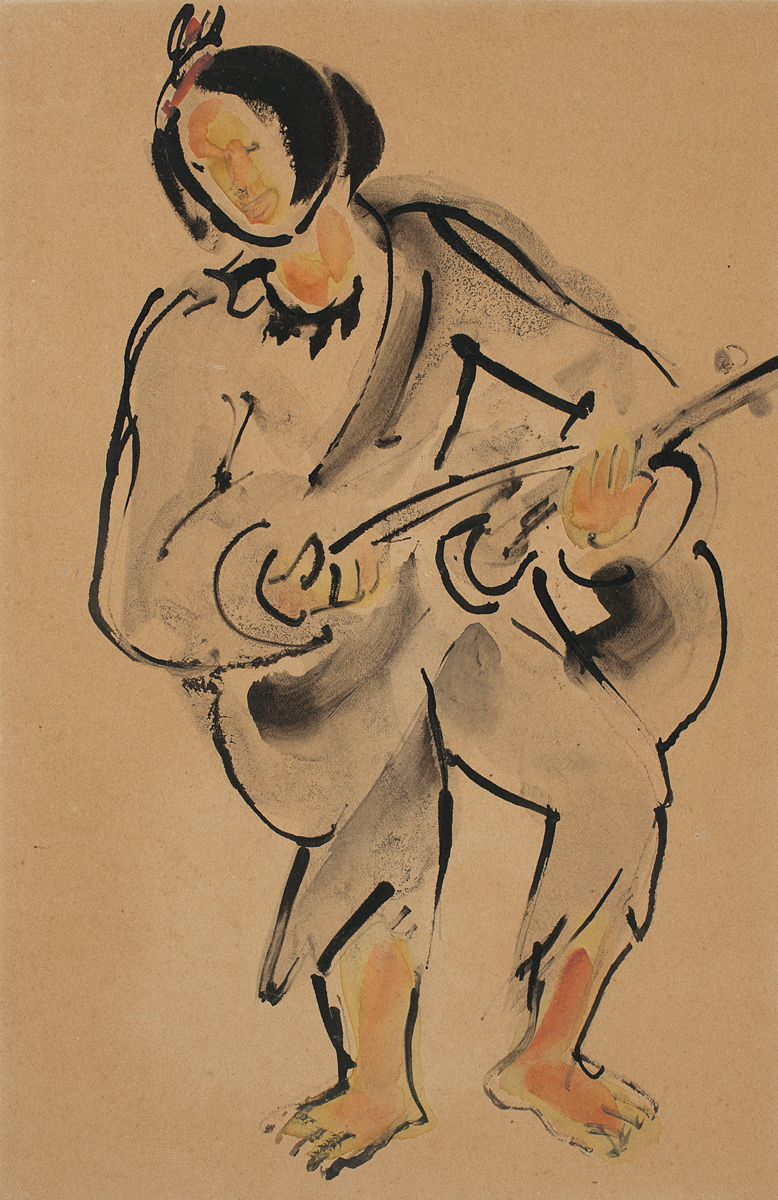

On SketchingRamachandran focuses on the relationship between Ramkinkar’s practice of sketching and sculpting, including making detailed preparatory drawings for his sculptural projects. As a sculptor Ramkinkar brought his own sensibility to the art of the sketch as well, even as he drew from a Santiniketan tradition of observational sketching developed by artists like Nandalal and Benode Behari Mukherjee. ‘Nandalal (Bose) started the tradition of sketching from life and nature through contour lines based on oriental practice (sic) of China and Japan. Kinkarda added the sculptural dimension to it. For animal studies, students first learnt to draw contour lines of the animals on the clay wall and build skeletal system (sic) on both sides. Strips of muscles were then added to the skeletal system which was covered by a thin layer of clay like the skin and finally the negative space of the wall (sic) removed. This exercise was done on the basis of scientific drawings of the skeletal and muscular systems. In the process, Kinkarda pointed out the differences and characteristics of each animal. The same process was used to explore human forms… This laborious exercise was to acquaint the students with the basic structure of each form. |

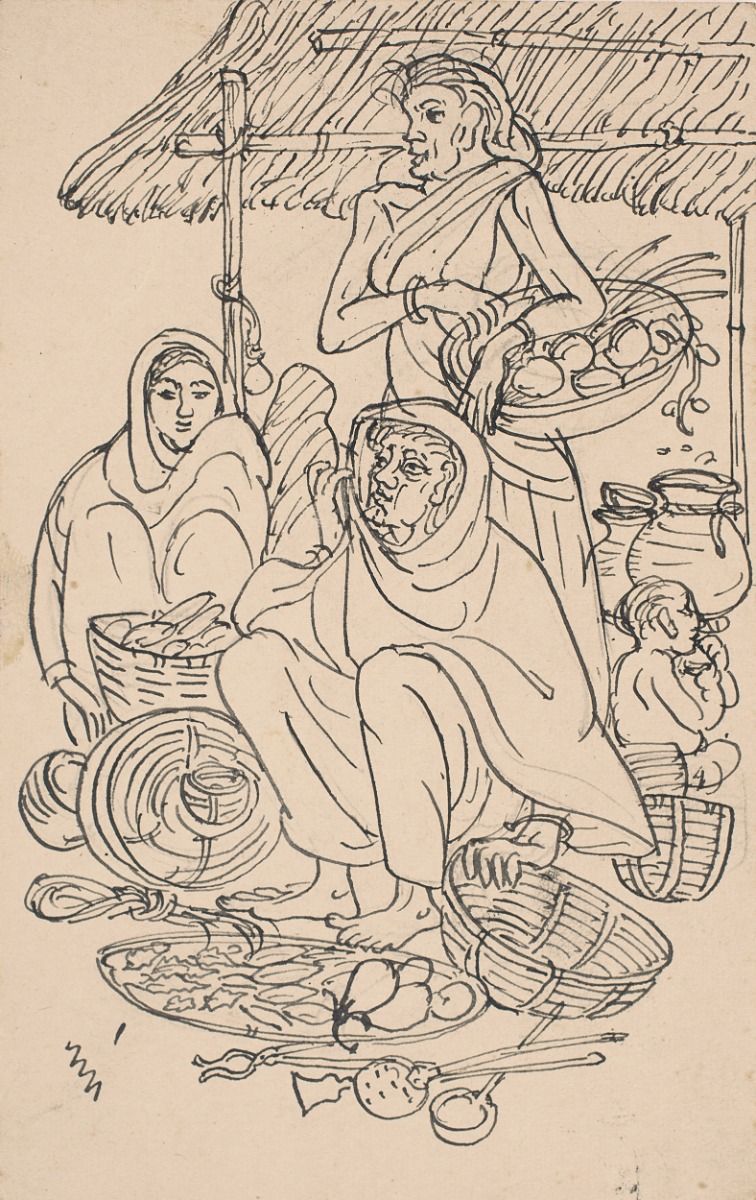

Benode Behari Mukherjee

Untitled

Ink on paper, 3.5 x 5.2 in.

Collection: DAG

Ramkinkar Baij

Untitled

Etching on paper, 7.2 x 5.2 in.

Collection: DAG

Kinkarda believed that only by understanding it, the artist could express conveniently on two or three dimensions and even take liberties with its usage… (Nandalal) knew that only through rigorous training of sketching, the artist could comprehend the basic principles of nature and develop his personality without settling down to a pre-determined ‘trademark’ style. Both Kinkarda and Benodeda (Benode Behari Mukherjee) followed the same logic. Whereas Benodeda chose the extreme simplicity of a fluid brushwork, Kinkarda being a sculptor added a bas-relief dimension. Thus he not only emphasized the contour lines, he defined the three dimensional possibilities of the image.’ |

|

The Minstrel ‘No one else has described the personality of Ramkinkar as precisely as K. G. Subramanyan, who called him ‘Khepa Baul’. This Bengali word refers to the mystic cult of Baul singers and their unconventional, detached way of life, wandering from village to village singing songs of love and god. Their negation of social norms and complete devotion to their art make them outsiders, hence society regards them as ‘Khepa’ or crazy. Kinkarda also led an unconventional life completely devoting himself to his art by producing a large body of robust works of great significance.’ |

|

|

Ramkinkar Baij

Untitled (Musician)

Watercolour and ink on paper, 11.2 x 7.5 in.

Collection: DAG

A. Ramachandran

Collection: DAG

The Inner EyeRamachandran acknowledged the foundational role played by Ramkinkar’s aesthetic vision and practice in his own life and art. He moves away from the orbit of Santiniketan, and only makes a couple of visits to see Ramkinkar in his last days. However, his lasting influence is visible in the artist’s own work, as traces of an impulse, but sometimes even more directly. ‘Within a span of seven years, Kinkarda left a deep impact on my life as a teacher, as well as an artist. Half a century has passed since then. In the twilight of my life, I realise that he had opened my inner eye and let me venture into the vast world of art and creativity to explore all the possibilities of my inner self, and to find my own path, and discover the promise of never-ending innovations. In that solitary search, I found that he had become an inseparable part of me all through my creative life. So closely fused has been his sensibility with mine that when I made my first monumental, totemic sculpture, years after I left Santiniketan, I juxtaposed the portrait of his head with mine.’ |