The Goddess Kali in Bengal modern artAnkan Kazi March 01, 2024 The evolving narrative of the goddess Kali’s depictions in Bengal modern art also highlights the intricate passageways through which folk and tribal artforms and practices infused the imaginary of the postcolonial modern in Bengal and India at large. While interfaces with a bustling urban culture—albeit one that was ‘compromised’ by its association with the colonial regime—provoked shifts in popular depictions of the goddess, especially in Kalighat pats, modernists trained consciously in the rules of academic art were gesturing beyond those confines by turning to the potent imageries and symbols associated with goddess Kali. Some of the greatest names associated with art in Bengal have made pictures of goddess Kali—from Prahlad Karmakar to Nirode Mazumdar and Rabin Mondal, with lesser-known masters adding their own personal visions to this heritage. In this story we will explore a few of these works. |

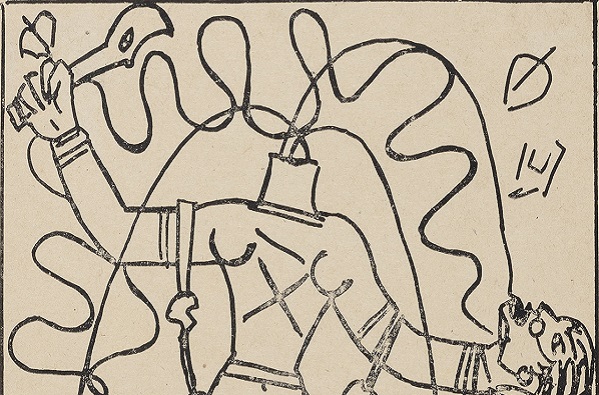

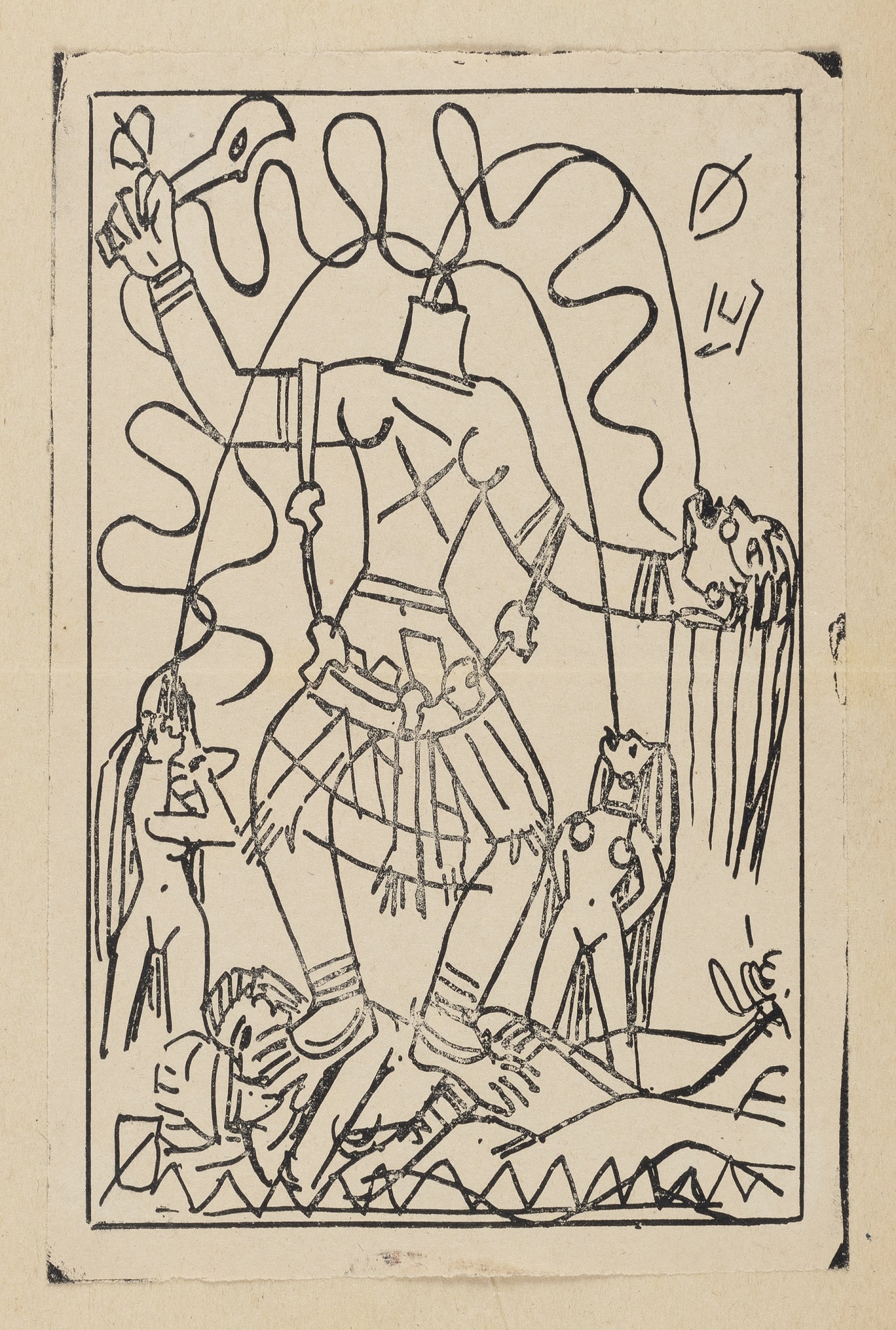

Nirode Mazumdar

Untitled (Chinnamasta) (detail)

Offset print on paper, 7.2 × 5.7 in.

Collection: DAG

|

Indian folk and indigenous art has influenced the depictions of Goddess Kali in several significant ways, imbuing her imagery with unique symbols, motifs, and interpretations that reflect the cultural and spiritual ethos of different communities. It is rich in symbolism, often drawing from nature, animals, and ancestral beliefs. In depictions of Kali by tribal artists, one may find the incorporation of symbols and motifs that hold particular significance within the indigenous culture it emerges from. For example, elements such as trees, animals, geometric patterns, and ritualistic objects may be integrated into the portrayal of Kali, enriching her imagery with layers of meaning derived from folk cosmology and mythology. These impulses would be absorbed by urban modernists seeking a way out of the impasse of a benighted, hegemonic national culture and empty gestures toward an international style. |

|

K. C. Pyne Kali 2000, Oil on canvas, 24.0 × 30.0 in. Collection: DAG |

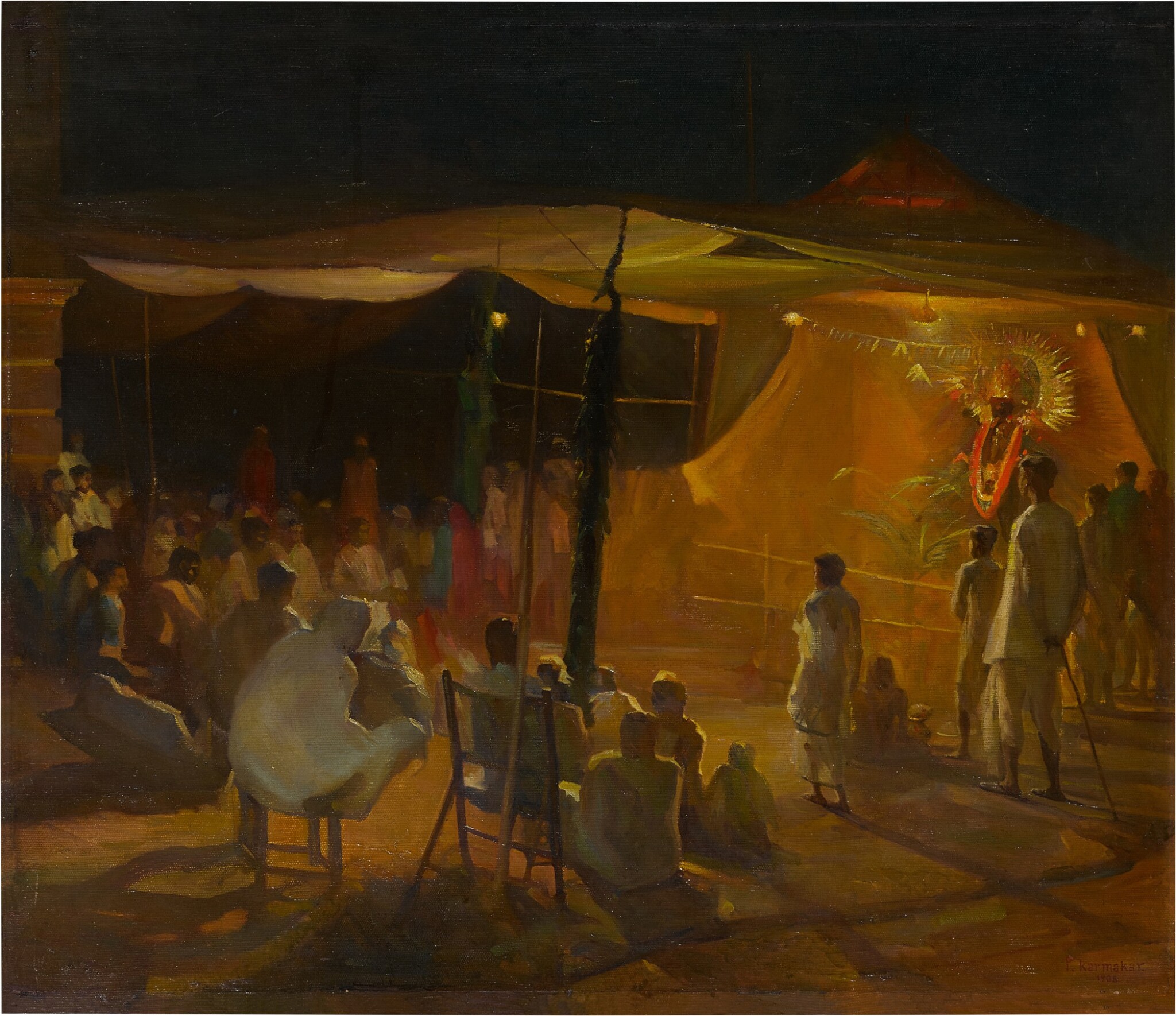

Prahlad Chandra Karmakar

Village Kali Puja

1938, Oil on canvas, 25.5 × 29.4 in.

Collection:DAG

Prahlad Karmakar was a renowned artist from Calcutta (now Kolkata) who lived from 1900 to 1946. He was known for his classical training and mastery in painting realistic scenes. He was one of the first artists to establish a studio with a nude study facility in Calcutta, a pioneering initiative at that time. He also served as a Senior Professor in the Department of Commercial Art at the Government College of Art and Craft in Calcutta. In his masterful depiction of an ongoing Kali Pujo, he arguably sets the tone for shifting the emphasis from imitative portraits and landscapes to visualising the social imaginaries of local traditions. Although the Dakshin Kali image has been painted faithfully, the largest section of the work focuses on the devotees of Kali—a dark and largely anti-social, if not anti-national, bunch in the colonial imaginary of his time. Followers of the goddess and its passionate devotees were often considered to belong to criminal gangs or tribes, and the atmosphere around rural Kali celebrations tended to attract the opprobrium of not just the colonial government but also urban bhadralok society. By introducing such elements of subversion into his academic art, Karmakar lays the ground for many future modernists who employed Kali to carry sinister messages of discord and danger that lay beneath the paved stones of polite society. |

|

Tribal art frequently employs simplified forms and bold, expressive lines to convey spiritual concepts and narratives. When depicting Kali, tribal artists may emphasize her essential attributes and divine essence through stylized representations that capture the primal energy and fierce grace associated with the goddess. These simplified forms often convey a sense of dynamism and vitality, inviting viewers to engage with the transcendent power embodied by Kali. This also provided a route towards assimilating trained academic practice with global movements in art that were increasingly turning to 'primitivist' or folk cultures to rejuvenate the iconographies and style of modern art by turning to simpler lines and forms that could carry complex local significations. |

|

|

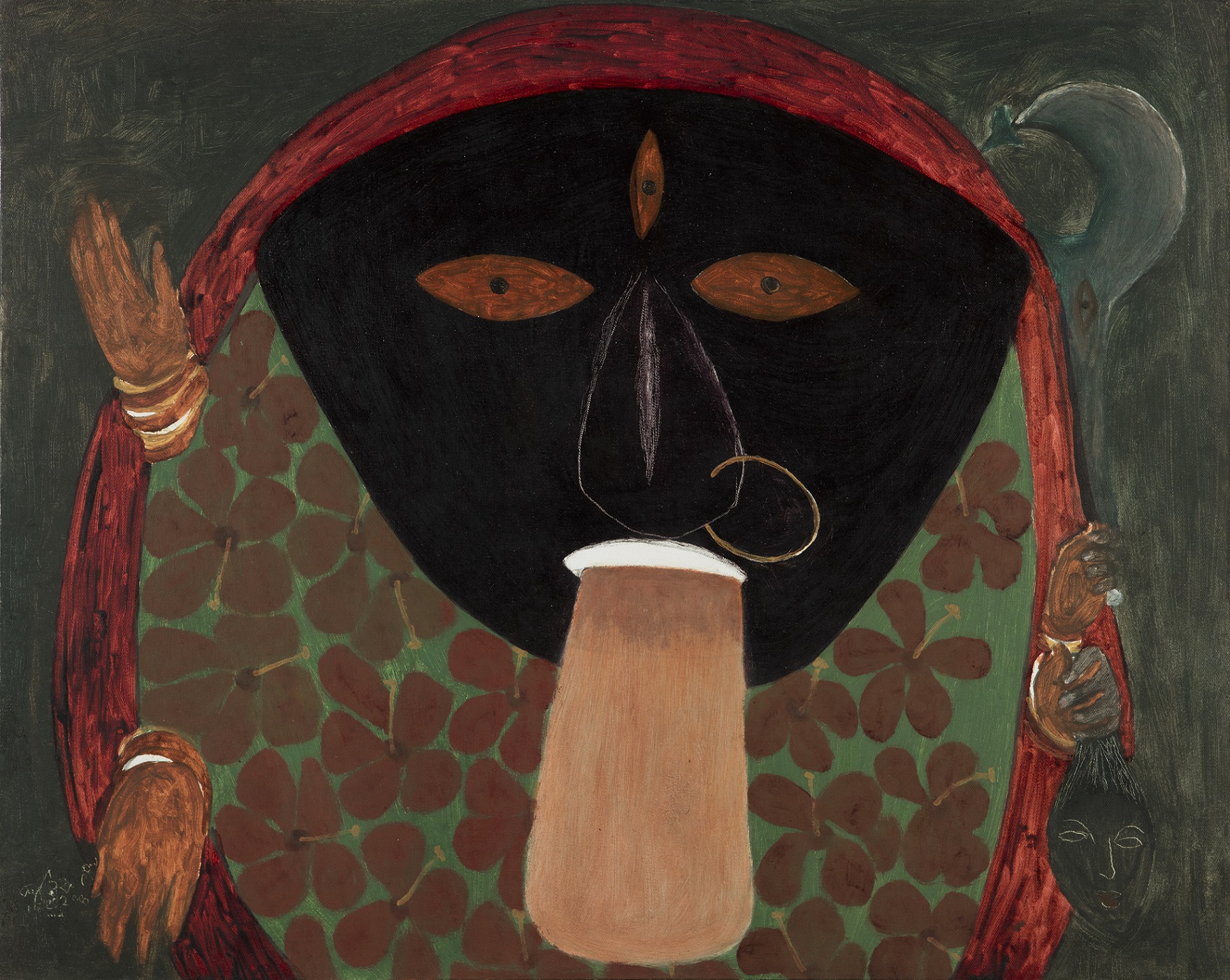

K. C. Pyne

Kali

2000, Oil on canvas, 24.0 × 30.0 in.

Collection: DAG

K. C. Pyne was a prominent Indian artist celebrated for his distinctive and emotive depictions of Hindu mythology, particularly his mesmerizing portrayals of the goddess Kali. Born in 1939 in Kolkata, Pyne emerged as a leading figure in the post-Independence Indian art scene. His conscious ‘primitive’ approach reveals the tensions between urban modern art and the strategies of folk art as well. Hibiscus flowers are believed to have purifying properties, both physically and spiritually. Therefore, offering hibiscus flowers in worship is believed to cleanse the devotee's mind and soul, preparing them for deeper spiritual experiences and connection with the divine. Fashioned as a simple chaalchitra that occupies the background like a halo, the salvific presence of a field of hibiscus flowers appears to purify the tainted colonial and urban culture of the city, within which the pure form of Kali manifests like a dark oasis of ambivalent grace. Moving away from Karmakar’s social emphasis, Pyne’s work critiques the sophisticated realism of academic art and personalises the goddess, much like an emotional shakta poet would do. |

Biswanath Mukerji

Goddess Kali

Gouache on recycled paper, 7.0 × 5.0 in.

Collection: DAG

Biswanath Mukerji

Untitled

1976, 5.0 × 7.0 in.

Collection: DAG

Biswanath Mukerji (1921 – 1987) was born in Varanasi, and spent most of his life in locations outside Bengal, such as Hyderabad and New Delhi. He was also a prominent member of art organisations in cities like Lucknow and Meerut, and initiated the annual children’s art exhibition in New Delhi. He also established an international gallery of children’s art at a public garden in Hyderabad. The influence of primitivism and children’s art, especially of the kind that communicates the force of a passionate vision over faithful imitation of objective reality, influenced his remarkable depictions of goddess Kali as well. Somewhat similar in temperament to Rabin Mondal and Pyne’s depictions, Mukerji’s bold works challenged the discourse of sophistication in modern art, securing it to a context of personal devotion. |

|

Depictions of Kali are deeply rooted in the cultural context of the communities that create them. Modernists like Karmakar attempted to show this communal aspect of Kali through their representation of the social groupings around such devotionalism. For others, the matrix of social and personal investments was translated through modernist methods like cubism which introduced fragmentation of perspective to highlight the multiple dimensions through which the goddess’ image operated. |

|

Biswanath Mukerji Untitled 1976, 5.0 × 7.0 in. Collection: DAG |

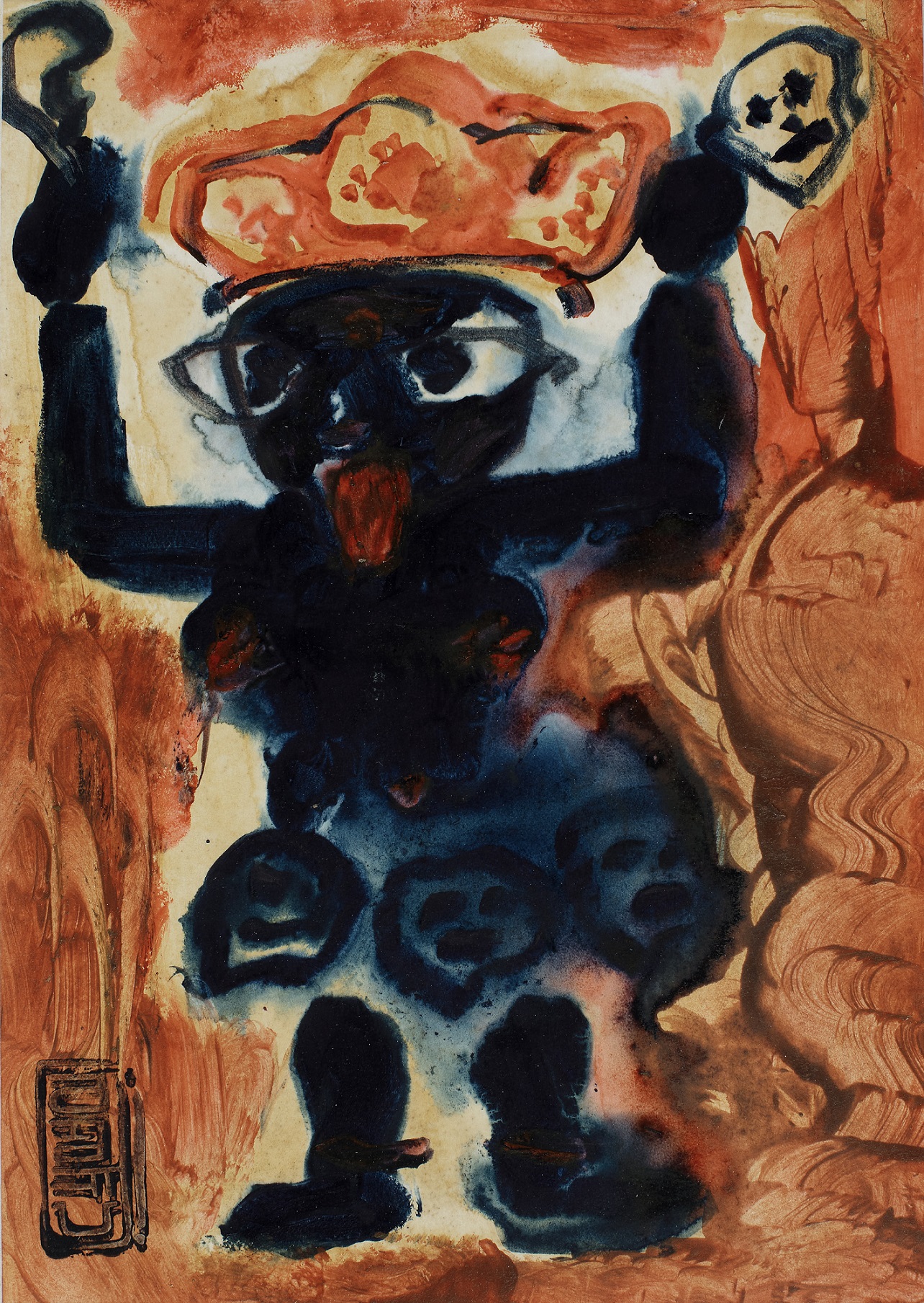

NIrode Mazumdar

Shodasi Kala

1970s, Oil on canvas, 39.2 × 31.5 in.

Collection: DAG

Nirode Mazumdar

Untitled (Chinnamasta)

Offset print on paper, 7.2 × 5.7 in.

Collection: DAG

Nirode Mazumdar, a prominent Indian artist born in 1902 in Bengal, is renowned for his profound exploration of spirituality and mythology through his art. His Kali paintings stand out as some of the most striking and emotive representations of the Hindu goddess, capturing the essence of her divine power and symbolism. Mazumdar's interpretations of Kali are characterized by their emotional depth and intense imagery. His use of colour and form further enhances the emotive power of his Kali paintings. Deep shades of black and blue dominate the canvas, evoking the primordial darkness from which Kali emerges. Yet, amidst the darkness, there are glimpses of radiant light, symbolizing the transformative potential inherent in Kali's destructive energy. In a book of shakta songs by Rampasad Sen, illustrated by Mazumdar, the artist highlights the more gaunt, skeletal aspects of the goddess’ terrible visage. His successful employment of cubist methods, learned from his long practice and residence in France, suggests an organic infusion of elements from Kali and Shiva’s mythic narratives of frenzied destruction onto an artistic method that critiques the place of realism in Indian modern art, whose heritage is so deeply soaked in devotional imagery. |

|

In some cultures, the depiction of Kali often extends beyond the realm of visual art to encompass ritualistic practices, ceremonial dances, and storytelling traditions. Through participatory forms of expression, such as communal rituals and performative arts, communities invoke the presence of Kali and invoke her blessings for protection, fertility, and spiritual renewal. These embodied forms of devotion reinforce the interconnectedness between the human and divine realms, fostering a sense of intimacy and reverence toward the goddess. |

|

Nirode Mazumdar Untitled (Chinnamasta) Offset print on paper, 7.2 × 5.7 in. Collection: DAG |

Rabin Mondal

Untitled (Tribal motif)

1994, Acrylic with oil finish on cardboard, 15.5 × 14.5 in.

Collection: DAG

Born in 1929, Rabin Mondal was a prominent Indian painter from Howrah, West Bengal. His artistic journey was deeply influenced by tragic events in his formative years, including the Bengal famine of 1943 and India's struggle for independence. Mondal's work is characterized by its expressionist style, reflecting the tormented humanity he witnessed in Calcutta. His paintings often depicted tragic figures, with some of his notable series focusing on ‘kings’ and ‘queens,’ as well as deities like Goddess Kali, showing his preoccupation with the nature of power and its effect on those that wield it. His art showcased a blend of cubist influences and expressionist elements, portraying themes of paranoia, fear, and suffering. During the nationalist period, Kali symbolized rebellion against imperial forces, resonating with various marginalized groups in Indian society. However, Mondal's interpretation of Kali goes beyond the conventional iconography, delving into the psyche of the goddess and the human experience. Through his bold use of colours, dynamic compositions, and emotive brushstrokes, Mondal infuses his paintings with a sense of dynamism and vitality, capturing the essence of Kali as both destroyer and creator, the embodiment of time and transcendence. It also seeks to dissolve the boundaries between perceptible forms and personal, hallucinatory visions, executed through his bold brushstrokes, almost suggesting an apparition invoked by mass hysteria. |

|

Even as the rich iconography of the goddess Kali became a means for artists to highlight various aspects of temporal and spiritual struggle, these experiments further expanded the vocabulary of modern art in India. It laid to rest the insistent question of whether religion had any place in modern art by highlighting the ways in which this repository could be refitted or reimagined in various ways. What are some of your favourite depictions of Kali in modern art? |

|

|