The Fifth Circle: Echoing the History of Mandi House

The Fifth Circle: Echoing the History of Mandi House

The Fifth Circle: Echoing the History of Mandi House

collection stories

The Fifth Circle: Echoing the History of Mandi HouseShreya Roy A roundabout—broad, elaborate, conscious and awake—spreads outward in seven rays of roads from its centre. Along these avenues stand institutions of art, forming a forum where culture continues, where it endures. This is the Mandi House circle, the capital’s epicentre of cultural life. In a vast country like India, where no single custom, ritual, or thought can ever capture the entirety of its cultural history, the institutions around Mandi House create a space that democratises art, sustaining traditions even as they evolve. |

Ramendranath Chakravorty

Untitled (Chitrangada series) (detail)

Coloured Linocut on paper, 8.7 x 8.7 in.

Collection: DAG

|

|

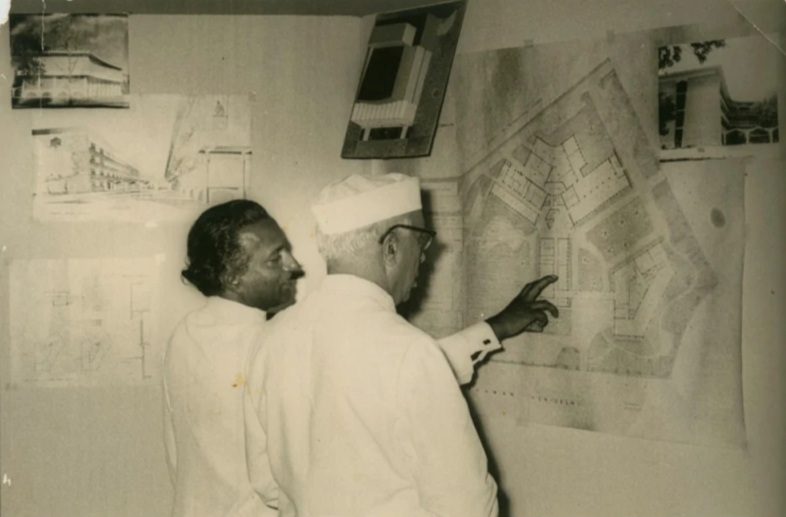

Jawaharlal Nehru and the architect Habib Rahman, discussing plans for the Mandi House

Image courtesy: Ram Rahman

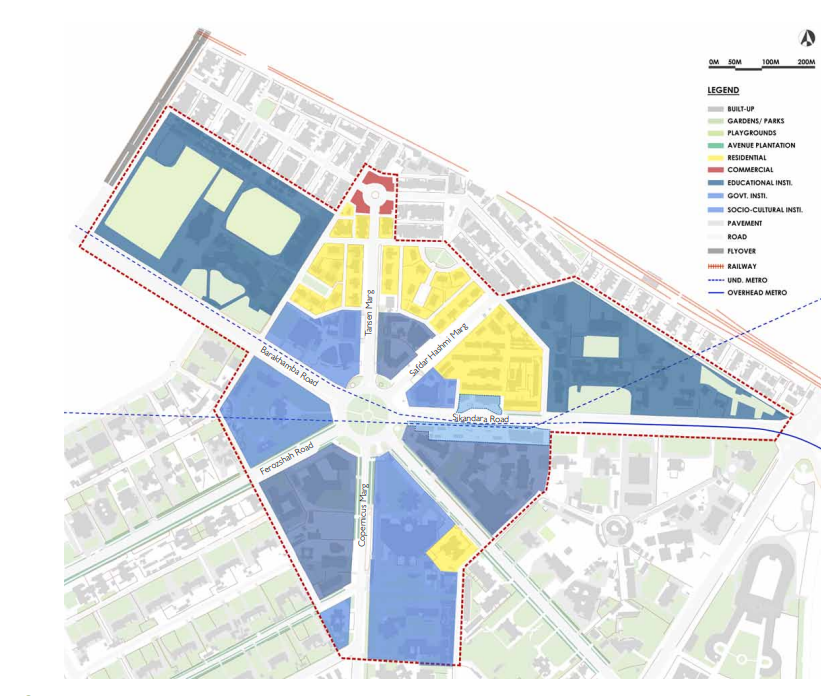

Map of the Mandi House circle

Image courtesy: Delhi Urban Art Commission

At Mandi House, culture took institutional form as part of Jawaharlal Nehru’s nation-building vision after 1947. Former royal estates were repurposed into government offices, while new buildings rose under Nehru’s direction. Portions of land were also allotted to private owners, who established their own institutions within the circle. Today, the area is defined by landmarks such as the National School of Drama, the Akademis of Lalit Kala, Sahitya, and Sangeet Natak, Doordarshan Bhawan, the Little Theatre Group (LTG), the Shri Ram Centre, and Triveni Kala Sangam—together shaping the cultural heart of the capital. |

|

But what was there before these institution-buildings came up? |

|

|

Bijay Sen (1846-1902), Raja of Mandi

Album of cartes de visite portraits of Indian rulers and notables

Bourne and Shepherd, c. 1870s

Image courtesy: Wikimedia Commons

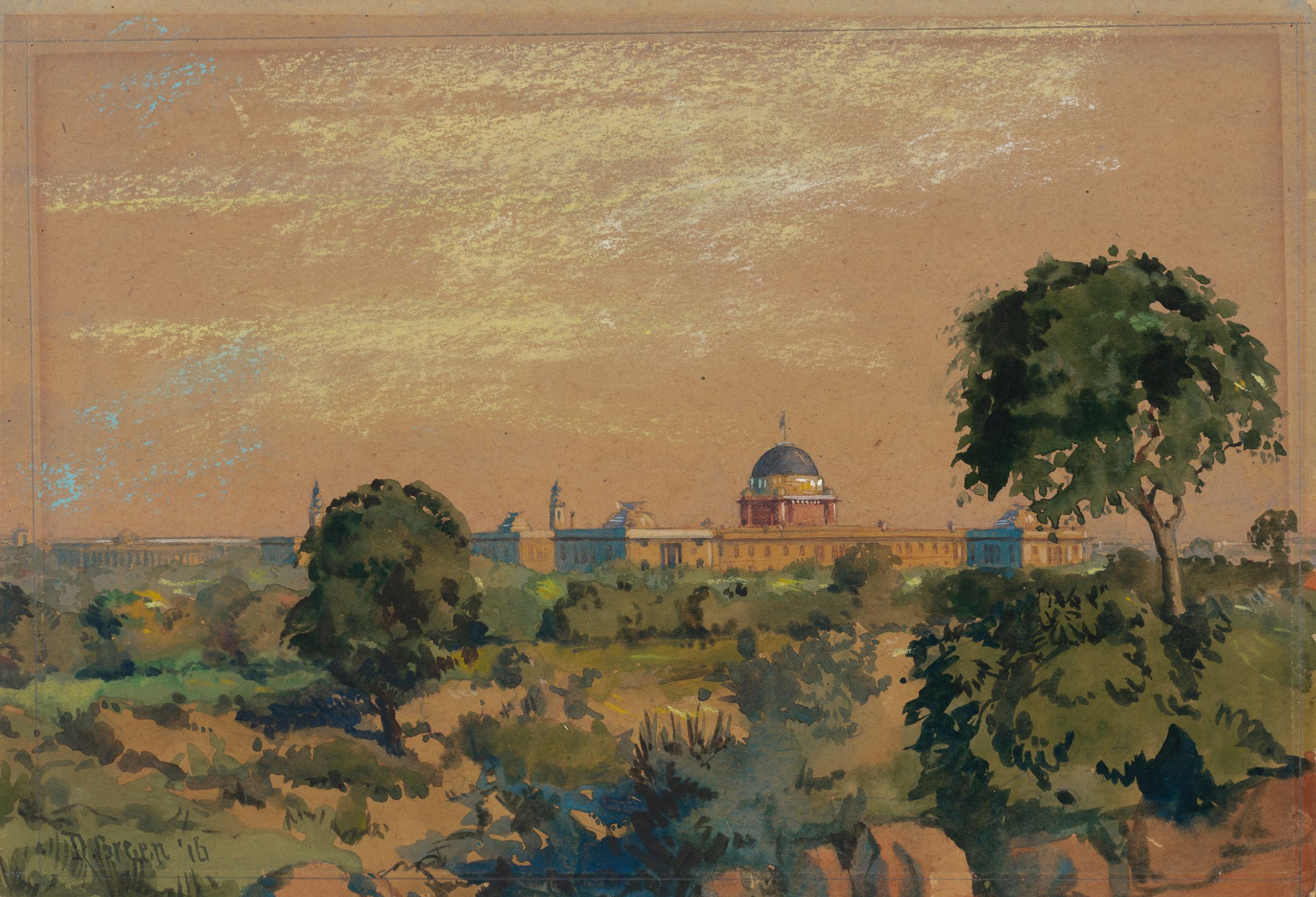

David Gould Green

View of Viceroy's House (now Rashtrapati Bhavan)

1916, Watercolour and pastel on cardboard

Collection: DAG

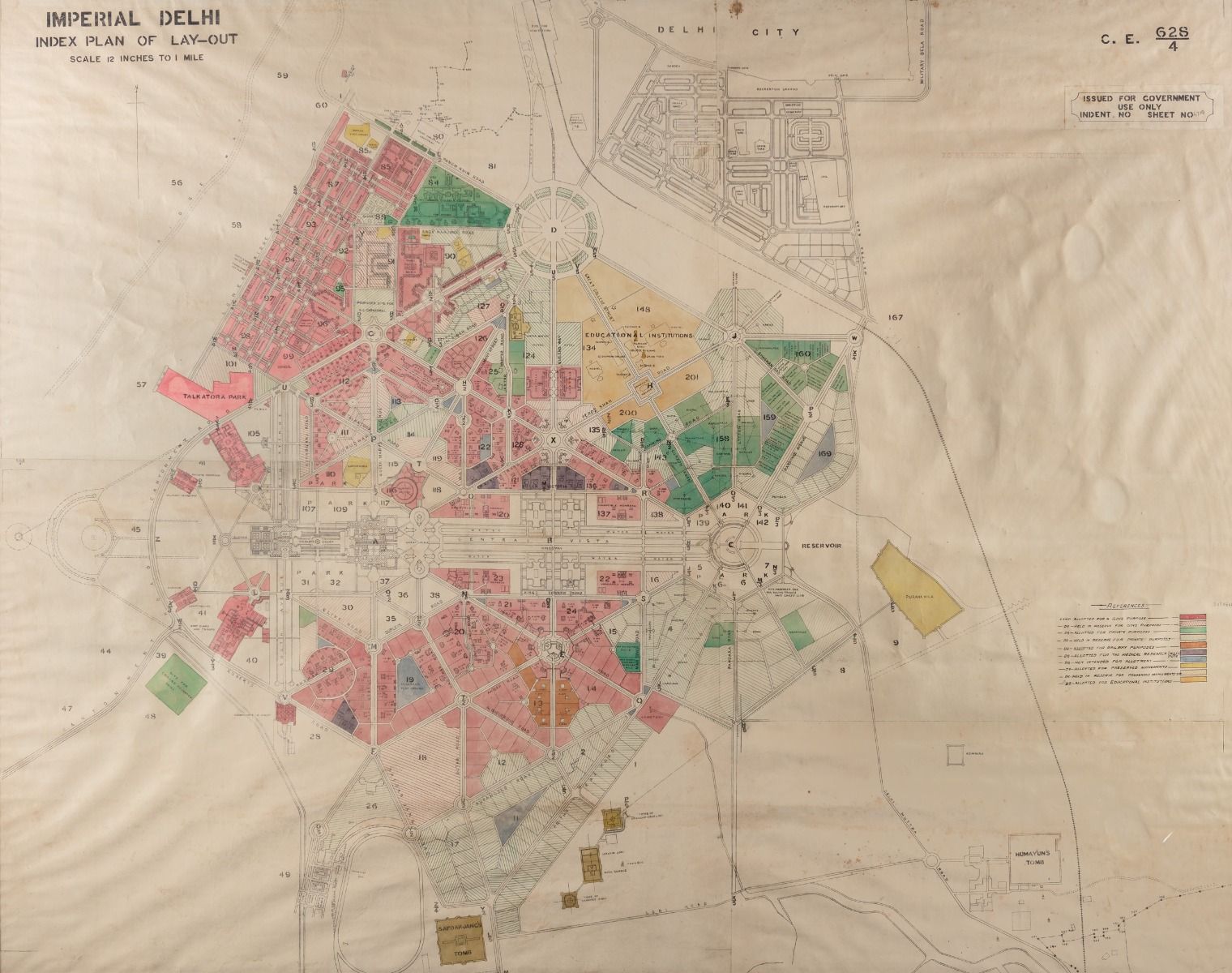

When the British decided in 1911 to shift their capital from Calcutta to Delhi, it led to the creation of a new imperial city—New Delhi. Two eminent architects, Edwin Lutyens and Herbert Baker, were entrusted with its design, which drew heavily on the neoclassical traditions of the European Renaissance, while attempting to accommodate Indian elements within them. Their vision aimed to project the majesty and authority of the British Empire at its zenith. Before 1947, however, Mandi House remained one of the more neglected parts of the city. On one side of the circle stood the palaces of the so-called ‘Chhota Nawabs’, while the other side was dotted with tombs—burial sites of the common people, many of which likely dated back to the Lodi dynasty. The palace of the King of Mandi state once stood here, on land that the Doordarshan Bhawan now occupies. It was this palace—the grandest among those of the area, alongside Nepal Bhawan, Bhawalpur House, and Nabha House—that gave the locality its name, Mandi House. |

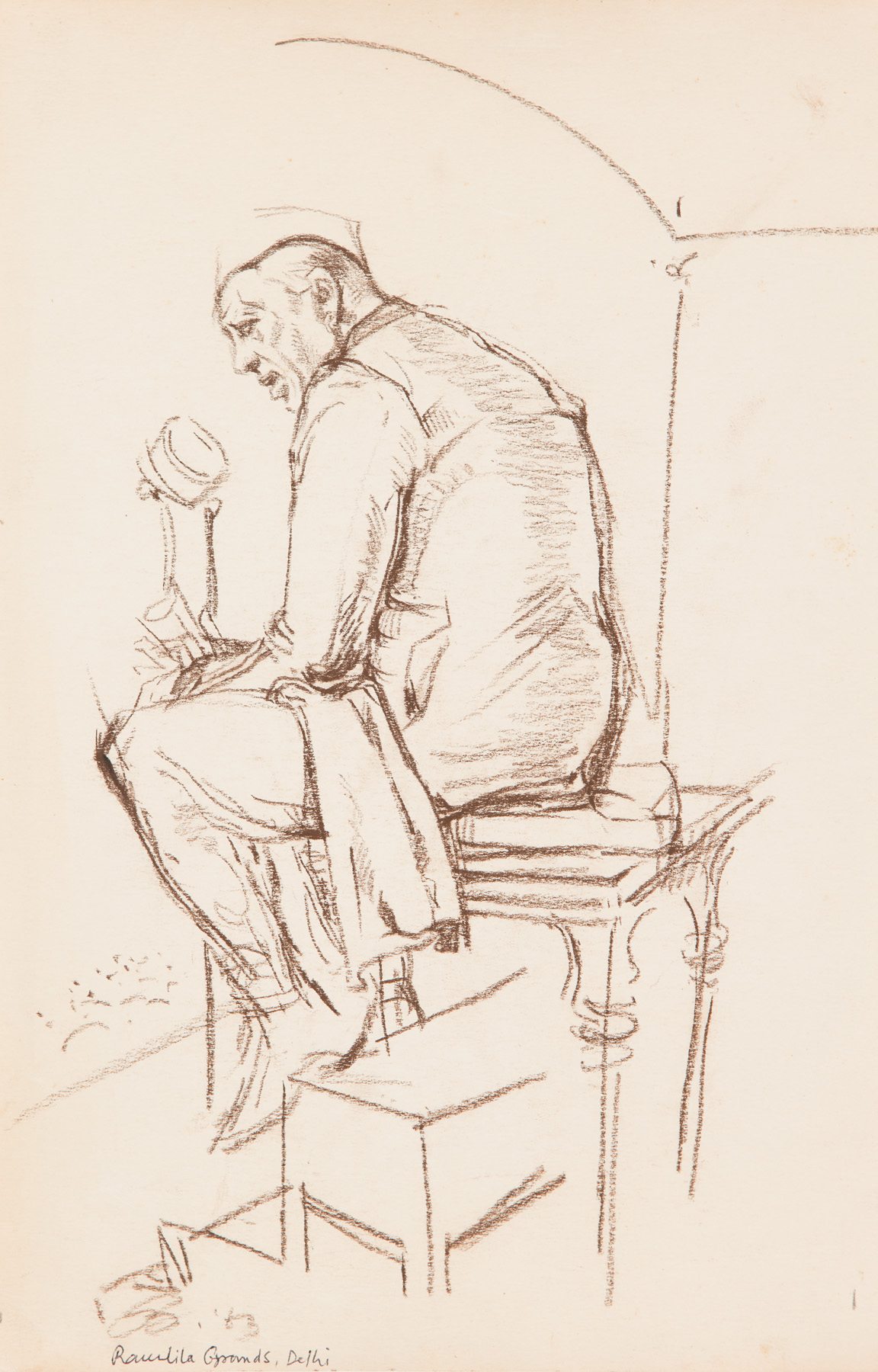

Biren De

Ramlila Grounds, Delhi

1963, Dry pastel on paper, 13.2 x 8.5 in.

Collection: DAG

At the time, the circle’s northern edge, hemmed in by a railway station and a sewage canal, was a quiet, unremarkable quarter of Lutyens’ Delhi. Yet, with Jawaharlal Nehru’s vision after independence, the area was transformed. By housing the nation’s leading cultural institutions here, Mandi House evolved into a vibrant hub where people could gather, create, and pursue art, fundamentally reshaping its social fabric. |

|

In the fervent years after independence, Jawaharlal Nehru and his cultural policymakers envisioned institutions that would both preserve India’s rich artistic traditions and shape a modern national identity through art, theatre, literature, and music. At the heart of this vision was the establishment of three national academies: Sangeet Natak Akademi for the performing arts, Lalit Kala Akademi for the visual arts, and Sahitya Akademi for literature. Founded between 1953 and 1954, these institutions were tasked with institutionalizing support for artists, writers, and performers; organizing awards, exhibitions, and publications; and serving as the nation’s representative bodies for both contemporary and traditional arts. |

|

|

Rabindra Bhawan, Delhi

Image courtesy: Wikimedia Commons

To house these three Akademis together, Nehru initiated a project: a dedicated building that would serve as the cultural nexus—a visible, symbolic embodiment of postcolonial India’s commitment to the arts. The idea was to mark the birth centenary of Rabindranath Tagore, making Rabindra Bhavan not just functional but symbolic. The architect assigned was Habib Rahman, then a senior architect with the Central Public Works Department (C. P. W. D.). Nehru personally engaged in the project, influencing design decisions. When Rahman’s initial proposal resembled a sterile office block with excessive louvres, Nehru rejected it. He challenged Rahman to produce something that would reflect Indian tradition, climate, and the aesthetic aspirations of the nation. |

Unidentified Artist

Imperial Delhi Index Plan of Layout

Ink on paper, hand tinted, early 20th century, 52.3 x 66.0 in.

Collection: DAG

The administrative block is Y shaped, with three wings at roughly 120° to each other, each wing housing one Akademi. Sahitya, Sangeet Natak and Lalit Kala occupy different wings. Its materials and motifs draw inspiration from Indian traditions—such as jalis (latticed screens), chajjas (projecting eaves), and Delhi quartzite stone—as well as from historical architecture, particularly Tughlaq-era forms, all reinterpreted to meet modern needs. Continuous reinforced concrete sun shades extend over the windows on cantilevered brackets, shielding interiors from the stark summer sun while allowing circulation of air. The exhibition or gallery block, by contrast, takes a pentagonal shape, its form following the curves of adjoining roads and traffic islands. In the decades after independence, as Rabindra Bhavan rose at Mandi House, it was soon joined by other cultural institutions, each similarly conceived in the spirit of nurturing the arts within a newly sovereign India. |

|

The Shri Ram Centre for Performing Arts (SRC) was established in 1958 by the Indian National Theatre Trust, a private initiative supported by industrialist Lala Charat Ram. The Centre’s building came up in the early 1960s, located prominently on Safdar Hashmi Marg. It was designed in a modernist style and houses a repertory company, performance spaces, and training facilities—serving as a key platform for contemporary Hindi theatre. |

|

|

Triveni Kala Sangam, Delhi

Image courtesy: Wikimedia Commons

Safdar Hashmi Marg, Delhi

Image courtesy: Wikimedia Commons

Around the same time, Triveni Kala Sangam moved into its permanent campus on Tansen Marg, built with land granted by the government. Shridharani began Triveni in a single room in Connaught Place with just two students. But her vision was expansive, she imagined a centre where painting, sculpture, music, dance, and drama would come together like the confluence of three rivers (hence the name Triveni). Her model was both pedagogical and democratic: art for all, beyond elite circles. Recognising her effort, the Government of India allotted her a plot of land in the Mandi House area in the early 1950s, as part of its cultural decentralisation drive. This was a time when the government, under the guidance of Nehru and Maulana Abul Kalam Azad, was encouraging the development of independent cultural institutions. Designed by Joseph Allen Stein, the building embraced a restrained modernist aesthetic, incorporating natural materials and open courtyards. |

Sudhir Khastgir

Untitled

1957, Watercolour, ink and pastel on rice paper, 28.0 x 19.0 in.

Collection: DAG

Minimalist modernist lines were softened by the use of natural materials such as Dholpur stone and exposed brick. Open courtyards, shaded walkways, and breezy verandahs evoked echoes of Indian temple architecture while also resonating with Bauhaus principles. At its heart lay a sculpture court, surrounded by studios, classrooms, and an auditorium—later joined by the Triveni Art Gallery, which soon became a crucial launching ground for contemporary Indian artists. Stein’s architecture rejected ornamentation and hierarchy, instead fostering openness and exchange. The design encouraged fluid movement and interaction across disciplines, drawing teachers, students, and visitors into dialogue. Informal yet vital, the amphitheatre, the Triveni Chamber Theatre, and the café emerged as cherished spaces for conversation, collaboration, and community. |

G. R. Iranna

Untitled

1995, Oil on canvas, 48.0 x 60.0 in.

Collection: DAG

The site where the National School of Drama (NSD) now stands was once the Delhi residence of the Nawab of Bahawalpur. After 1947, the estate—like many other princely properties in the area—was taken over by the Government of India. For a brief period, Bahawalpur House housed the United States Information Service, and students frequently visited its American Library to read and access resources. Soon, Mandi House also evolved into a prominent site of political expression. It became a favored gathering point for protests, a space that students, in particular, began to claim as their own. The tradition of demonstrations here began in 1969, when crowds assembled around Bahawalpur House to protest against the Vietnam War. It was on this very occasion that renowned theatre artist M. K. Raina directed his first street play, performed along Sikandra Road in front of the building. The National School of Drama (NSD) was established in 1959 by the Sangeet Natak Akademi as a national theatre training institute, following a 1954 proposal supported by Nehru. Around the same time, the Asian Theatre Institute (ATI), founded with UNESCO support, was merged into NSD, which began as the National School of Drama and Asian Theatre Institute in Nizamuddin West. That same year, after touring many homes and experimental theatre spaces, NSD moved to its permanent home in Bahawalpur House. The mansion was repurposed into a vibrant cultural hub under the visionary leadership of Ebrahim Alkazi, who laid the foundation for NSD’s artistic legacy. |

|

Doordarshan Bhawan was designed in the 1970s by renowned Indian architect Raj Rewal. The building reflects a distinctive blend of modernist and brutalist architecture, characterised by exposed concrete structures and a monumental scale that aligns with India's post-independence architectural vision. The premises symbolise the paradigm shift of Indian broadcasting from state-run radio to nationwide television. Architecturally, the building represents a deliberate transition from colonial styles to a more indigenous and functional form of modernism, using local materials like sandstone and adapting to India’s climate and cultural context. |

|

|

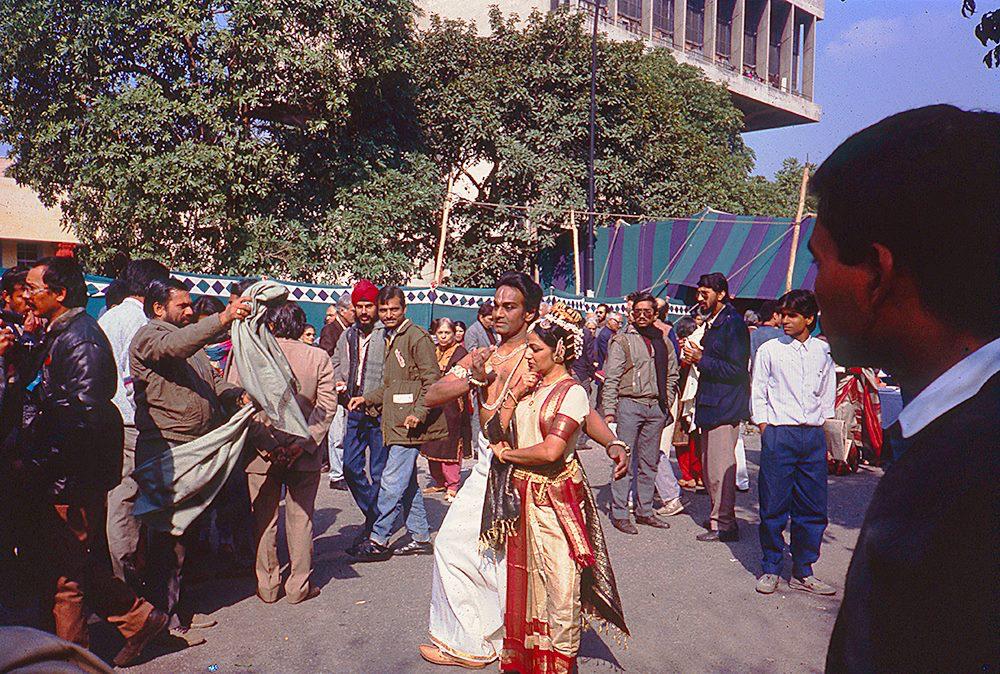

Raja and Radha Reddy

Sahmat Artists Against Communalism, Safdar Hashmi Marg, Mandi House

Image courtesy: SAHMAT

Mandi House’s role extends beyond formal stages to the streets and public spaces surrounding it. These open areas have historically been vital rehearsal grounds and performance spaces for street theatre groups known for their socially engaged work. Among the most prominent was Jana Natya Manch (JANAM), founded by the activist and playwright Safdar Hashmi. Janam used street theatre as a powerful tool to raise awareness on labor rights, communal harmony, and government accountability. Their performances, often staged in and around Mandi House, attracted public attention and mobilised audiences beyond traditional theatre-goers. Most importantly, Mandi House quintessentially was the rehearsal space for JANAM. |

|

Today, the Mandi House circle has become a VIP zone where cars don’t stop at traffic signals, changing the nature of human interaction and diminishing the area’s vibrant spirit. Many who grew up here—as students, artists, and engaged citizens—long to restore the old charm: a place for endless conversations, where students could afford to spend hours brainstorming over chai and snacks. They envision a community hub enriched with bookstores and a more inclusive atmosphere that nurtures art alongside craft. As the unnamed fifth pillar of democracy, culture stands as both an extension and living practice of the fifth Veda, Natyashastra. This circle, dedicated to preserving art and cultural traditions, truly embodies the fifth circle of Delhi. |

|

|