The Enigma of Arrival: F. N. Souza in London

The Enigma of Arrival: F. N. Souza in London

The Enigma of Arrival: F. N. Souza in London

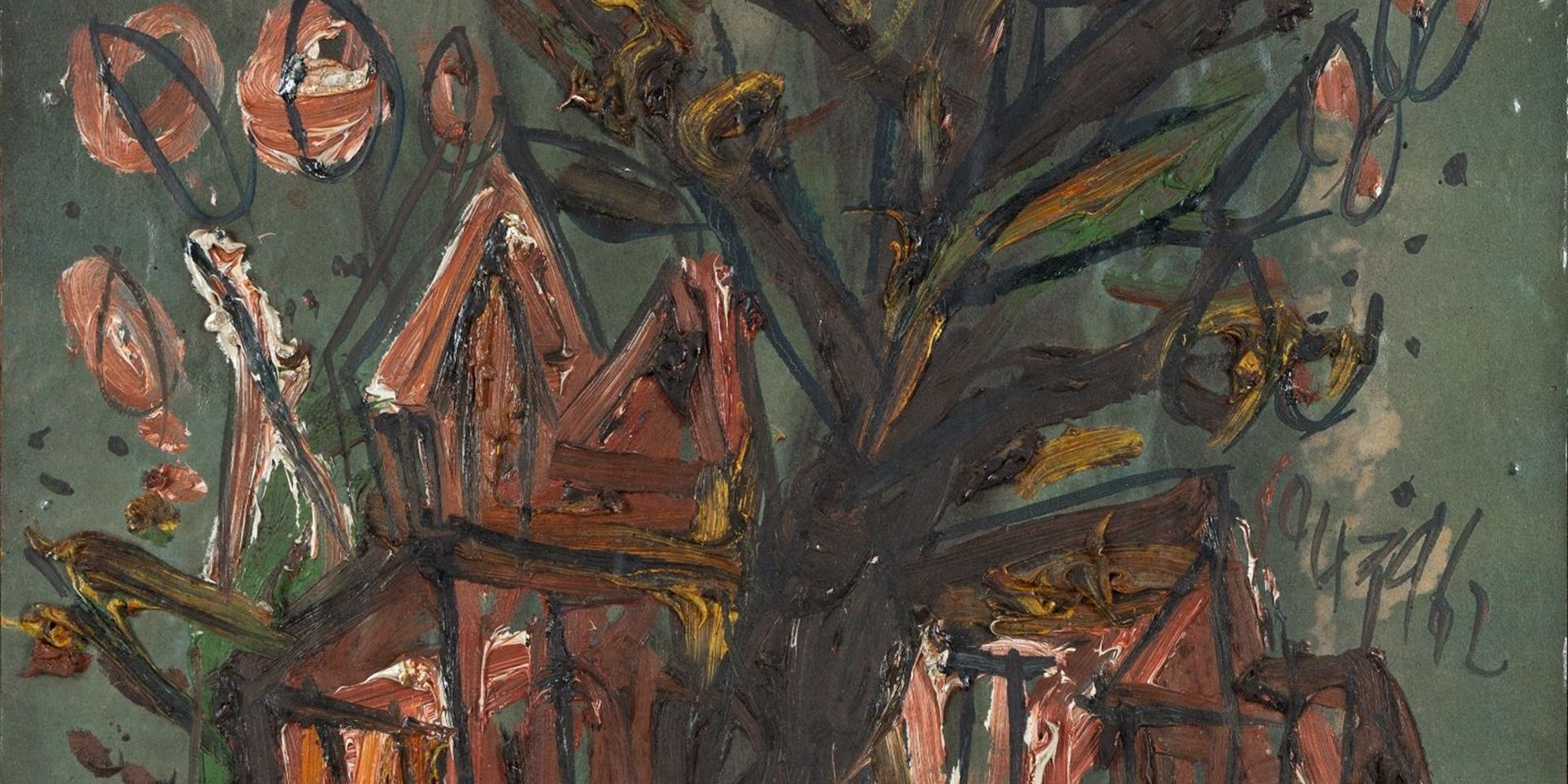

F. N. Souza, Red House and Tree (detail), 1962, Oil on magazine paper pasted on board, 10.2 X 13.7 in. Collection: DAG

‘How could people like these, without words to put to their emotions and passions, manage? They could, at best, only suffer dumbly. Their pains and humiliations would work themselves out in their characters alone: like evil spirits possessing a body, so that the body itself might appear innocent of what it did.’

V. S. Naipaul, The Enigma of Arrival: A Novel in Five Sections

The twentieth century witnessed an unprecedented convergence between writing and painting, driven by shared impulses toward innovation, abstraction, and social critique. As artists and writers navigated new realities shaped by war, colonial violence, identity crises and cultural revolutions, they found in each other’s work both inspiration and reflection. Abstraction became important in both writing and painting. Artists and writers began to stretch language and change how we describe everyday experiences. This conversation continues to shape modern practices, showing that the lines between visual art and literature are flexible. In the context of the development of Indian modern art, especially, artists who wrote influential works still make up the cornerstone of aesthetic discourse in South Asia. Abanindranath Tagore’s philosophical and categorical formulations in his lectures on art and Indian aesthetics became standard texts; and Benode Behari Mukherjee’s personalised essays established a more poetic pact between the related acts of writing and painting, rooted in sensation.

|

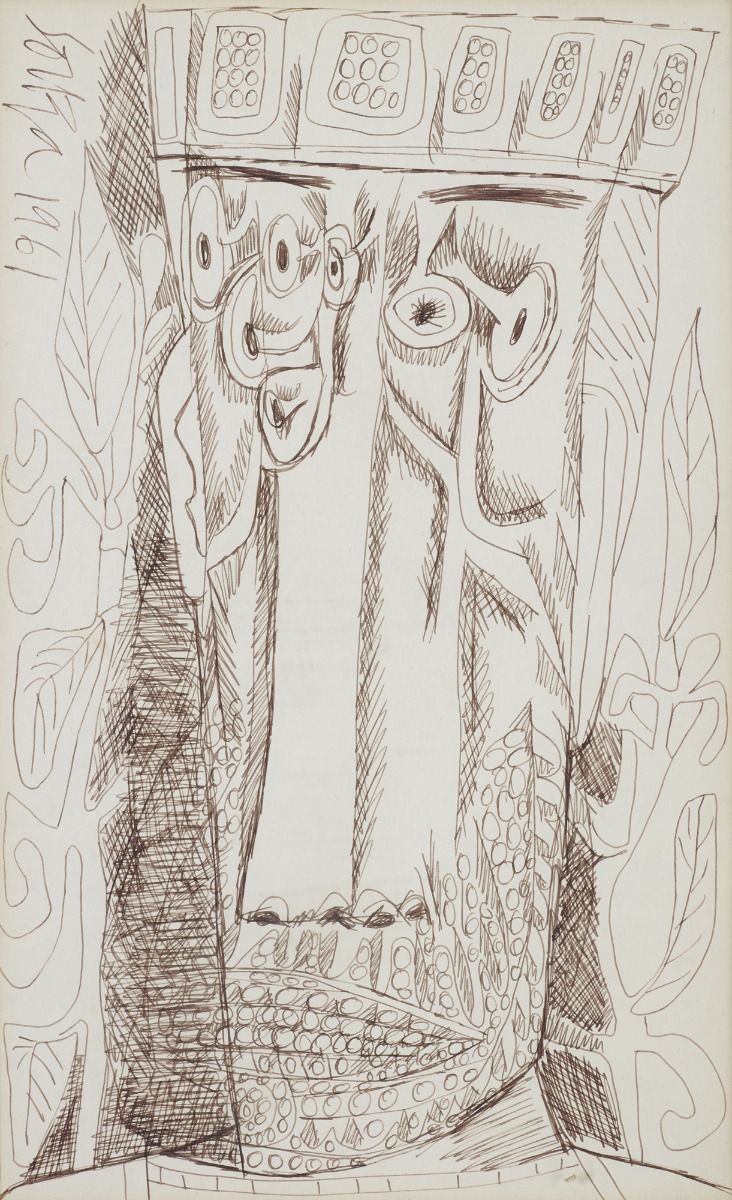

F. N. SOUZA, UNTITLED (EMPEROR), 1961, Pen and ink on paper, 12.7 x 8.0 in. / 32.3 x 20.3 cm. Collection: DAG |

For an artist like F. N. Souza, writing and painting were allied acts, although he saw himself as a ‘failure’ in the former craft and an unabashed ‘victor’ in the latter. Travelling to London as a penniless artist from India, belonging to a mixed heritage of Portuguese-Goan descent, his writings illuminate a dense, often turbid, psychological hinterland, made up of stories, experiences and historical narratives, that constituted a supplement to his stark, often provocative, work in drawing and painting. A lot of his success in London is owed to the publication of his memoir-piece ‘Nirvana of a Maggot’ in the magazine Encounter, which was edited by the poet and leading English intellectual of the time, Stephen Spender.

|

Stephen Spender. Image Courtesy: Wikimedia Commons |

The Encounter magazine, founded in 1953 alongside journalist Irving Kristol, emerged as a significant intellectual and cultural journal during the mid-twentieth century. Published monthly in the United Kingdom, it aimed to foster a dialogue between Anglo-American literary and political thought, showcasing a diverse array of contributors from both sides of the Iron Curtain. The magazine quickly became a platform for prominent writers, poets, and critics, reflecting Spender's commitment to literary excellence and cultural discourse. Elsewhere, in a book titled The Struggle of the Modern, where he discussed the London art world as well, Spender articulated a critique of modernity focusing on the role of the individual self, stating, ‘Great poetry is always written by somebody straining to go beyond what he can do.’ This assertion encapsulated his belief that true artistic expression emerges from the struggle against limitations—both personal and societal. Spender's poetry often reflected his own struggles with identity and belonging, particularly as a gay man in a society that was not always accepting. These challenges would be reflected in Souza’s attempts to articulate his own struggle as well.

|

F. N. Souza, Untitled. Collection: DAG |

However, it should be noted that Encounter's legacy was marred by the revelation of its covert funding by the C. I. A. through the Congress for Cultural Freedom. This connection came to light in 1967, leading to significant controversy and the resignation of both Spender (and later, Frank Kermode) as editors. Spender maintained that he was unaware of the C. I. A.'s involvement until the revelations surfaced, which cast a shadow over the magazine's editorial independence, and which should also encourage us to read Souza’s text against the larger global-political framework of Cold War politics. Although many sources claim that Souza was active during the Quit India Movement of 1942—which allegedly led to his expulsion from Bombay’s J. J. School of Art—he does not write about these experiences in the autobiographical pieces collected in Words & Lines, which includes Nirvana of a Maggot. He does mention his involvement with the Communist Party though, and his growing frustration at their attempts to control or dictate how or what he should paint. It would lead to his departure from the Party. Less than a decade later, Nirvana of a Maggot would appear in Encounter. While his involvement with the Communist Party could be read as part of a larger global community of resistance against modern consumerism, his specific involvement in Indian political activities get somewhat erased in these texts, perhaps influenced by a consideration of the reader-demographic of the magazine.

Despite the controversies, Encounter played a crucial role in shaping post-war literary culture. It served as a meeting point for various intellectual currents and facilitated discussions on pressing social issues, gathering a range of dissonant, critical voices under a complex (perhaps even compromised) conception of global, progressive politics. Spender played a crucial role in introducing Souza to the art world in London, which significantly impacted his career. After Spender connected him with art dealer Victor Musgrave, Souza achieved notable success with a sold-out exhibition at Gallery One in 1955. This collaboration marked a turning point in Souza's life, allowing him to gain recognition and establish himself as a prominent figure in contemporary art. Ten years later, he would write a letter to Robert Melville, reproduced below from the DAG archives, where it is clear that Souza thought of himself as a ‘great painter’, whose challenge was to find a ‘big enough art dealer to manage him.’

|

F. N. Souza, Text, 8.0 X 5.2 in. Collection: DAG |

The Anxiety of Influence

In the text A fragment of Autobiography—one of the earliest published by the artist—Souza reflects on the early years of his life in Goa. Beginning with an account of his grandparents, who lived in Assolna, Salsette and were ‘chronic drunkards’, he writes that his father chose to abjure alcohol altogether and moved, eventually, to Saligao, Bardez, where he met Souza’s mother and married her. Although the account affects light-heartedness, it is shot through with traumatic early life incidents, such as the death of his father and elder sister, and his own near-fatal small-pox affliction. Thereafter, his mother was forced to move to Bombay (now Mumbai) to seek jobs—eventually finding a career as a tailor. Souza writes that he ‘took lessons from her in tailoring, as a safety measure should I prove unfit for other professions, being a duffer at school.’

These reflections also tell us about Souza’s earliest orientations in an art education. Even though he enjoyed the spectacle of Catholic service and the appearance of the whitewashed churches across Goa, he felt little attraction for the implied faith that activated these external forms. The colonial establishment, complicated by Goa’s historically contingent encounter with Portuguese rule (which would nominally be in place until the early 1960s), prefabricated certain ideas about Indian art. He writes, ‘I was… brought up to believe that Hindu sculpture and Mogul paintings were graven images of the heathen.’ He writes about leaving for London in 1949 and asserts his independence which was hard-fought for. ‘Today’, he writes, ‘I am one of the very few painters who lives entirely on his art without resorting to teaching or commercial portraits.’ This is similar to claims made by other Indian writers who tried to make it in the erstwhile colonial metropolis, such as V. S. Naipaul, whose books would proclaim that he followed ‘no other profession’ other than writing. Souza refuses to claim that he ever ‘experiment(s)’ and ‘can confidently say that (he was) not influenced by anyone’.

|

F. N. Souza, Untitled, 1971, Lithograph on handmade paper, 11.5 X 16.5 in. Collection: DAG |

Writing more directly about art—he recounts his early efforts at drawing, of which he is proud, noting that he would offer to correct the dirty graffiti drawn on his school’s bathroom walls. Then he writes about his struggle to free himself from the dictates of art, so that his work could only express his own feelings. Through a process of negation, writing that he does not wish to paint for an elite coterie or a proletariat, and that he is not interested in reproducing patterns either, he writes that ‘It is the serpent in the grass that is really fascinating. Glistening, jewelled, writhing in the green grass. Poisoned fangs and cold-blooded. Slimy as squeezed paint.’ Through such sexually loaded, psychological turns, Souza confirms that ‘I do not unwrap myself when I paint. I unwrap myself when I write.’

‘to emit sounds with gummed backs like postage stamps’

In his text Nirvana of a Maggot, Souza deepens this relationship between a writing that offers transparent psychological access and painting that is an agglomeration of forms and heroic depiction of a flawed but endlessly alluring modern. He writes about his stay in an ‘almost deserted village in Goa… in an old half dilapidated house.’

F. N. Souza, Red House and Tree, 1962, Oil on magazine paper pasted on board, 10.2 X 13.7 in. Collection: DAG

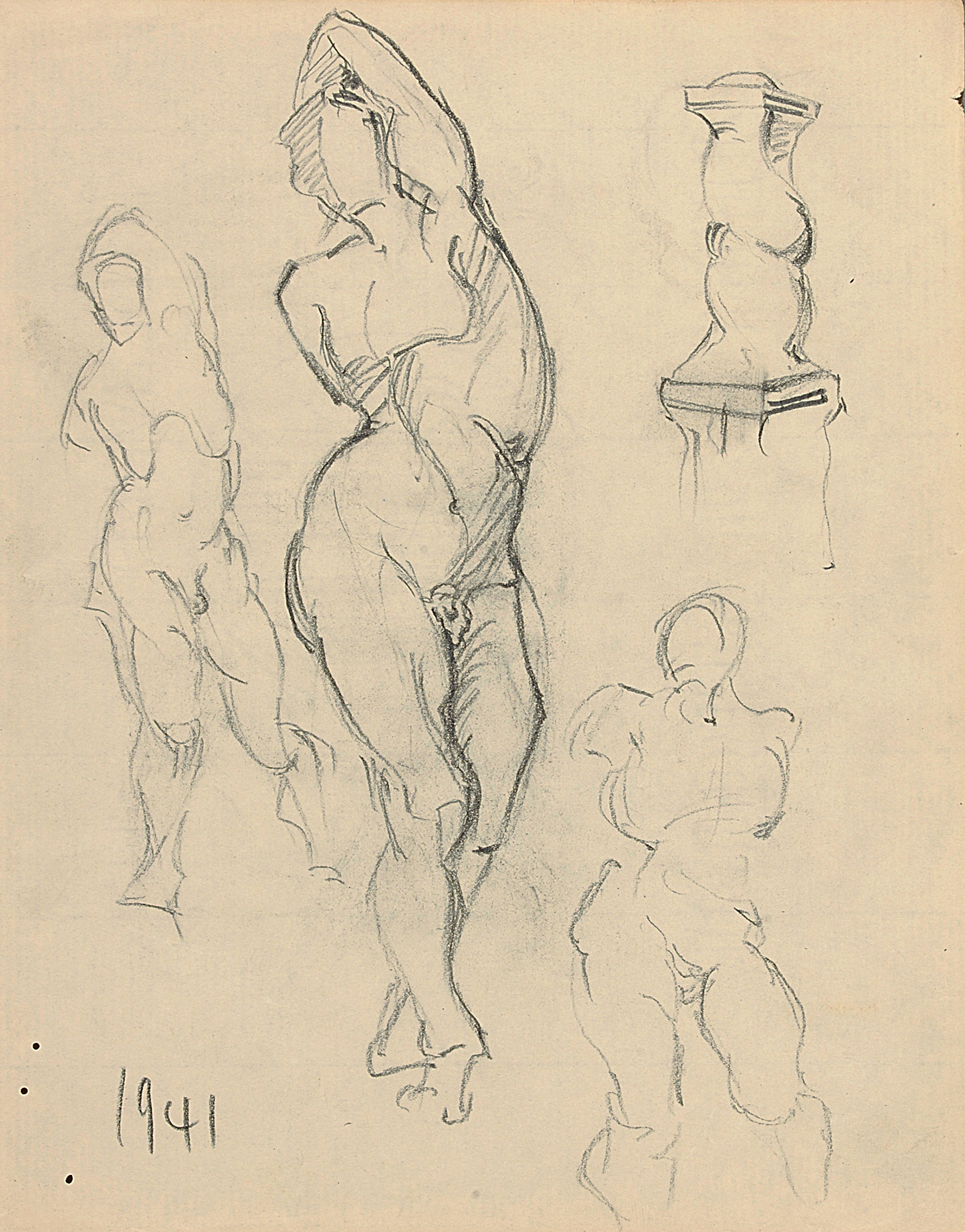

He describes his daily routine in this idyll, and the physical effort that was required to clear a space for his painting efforts—reflecting, once again, a psychological need to construct his own space in modern art. He also says that ‘I used to write a lot too. But whenever I write, I get a feeling of incompetence. Not so when I paint, for then I feel I am the master of the situation. Words, however, to me are very elusive little things and they fail me… What I’d like to do first of all is to merely articulate freely and easily.’ The effort to articulate his practice, with which is tied up his historical being in the world of postcolonial London, illuminates a process of study as well. Articulation refers to the point where two or more bones meet, forming a joint. And if one takes a closer look at the mass of correspondence Souza generated, or the notes he made for himself, studying the joints of the human body—one can find more direct traces of the shadowy line that separates his art from his writing. What follows this admission of failure to write, is a stream-of-consciousness that links the act of writing to painting through a deliberate break in the grammar of both arts. In the light of his previous autobiographical fragment, for instance, where he described his acts of creation as ‘slimy as squeezed paint’, compare his writerly/ speechmaking intentions when he writes: ‘I’d want my language to ooze out of my mouth naturally, pure like a bubbling spring, a fountain spurting out…’ Souza writes that such ‘a language may have no orthography’, connecting his inability to express himself through writing to a loss of ‘power to make a sound’ or craft a recognisable form. The struggle to construct an independent voice bleed across the acts of writing and painting for Souza, an inadequacy in the one providing a source of supremacy in the other.

|

F. N. Souza, Text, 8.0 X 6.0 in. Collection: DAG |

|

F. N. Souza, Untitled, 1943, Graphite on paper, 8.0 X 6.2 in. Collection: DAG |

When Words & Lines was republished in the mid-1990s, Souza joked about his early efforts in writing as half-forgotten relics of his larger creative practice, although he notes proudly that it was admired by others at the time. He emphasised his inspiration in nature, which bounds across the collected texts, in descriptions of the Goan landscape—which has been a regular subject in much of his work, including its dark, dilapidated houses, its churches and its almost-misbegotten people, whom he painted in satirical series such as ‘Six Gentlemen of Our Times’. How much he transfers his own psychological wounds onto the surface of these works is open to question; but the subterranean link that he sought to build between a sexually charged sense of self and navigating the new, professional world of post-war London is revealed by his fragments of writing.