|

DAG Recommends The Comic Art of PropagandaThe Editorial Team June 01, 2023 Due to their narrative capacities, comic books have been regularly adapted to highlight national achievements of freedom, resistance to imperialism and cultural distinction. These are stories that people tell themselves about their own cultural creation or their own greatness over others. The word ‘propaganda’ can be easily used to describe most of these, but it doesn’t tell us much about the affective registers and specific social imaginaries that are in play with each of these works. As forms of strategic essentialism, propaganda can serve the desires of a corrupt political regime as much as it can drive benevolent projects of nation-building and strengthening community bonds, along with promoting broader cultural agendas of decolonization. Let’s take a look at some illustrated works from the twentieth century (and one from the eighteenth century) that attempt to re-orient our normative views of the historical trajectories of the time, especially addressing the theme of decolonization. |

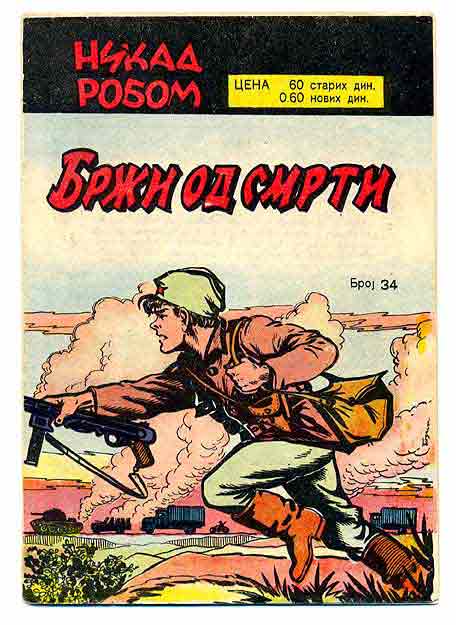

Detail from a cover image for Mirko i Slavko.

Image courtesy: Nikad Robom

|

‘…’Tis a Common Observation here that our Cause is the Cause of all Mankind; and that we are fighting for their Liberty in defending our own. ’Tis a glorious Task assign’d us by Providence; which has I trust given us Spirit and Virtue equal to it, and will at last crown it with Success.’ -Benjamin Franklin |

|

Benjamin Wilson, Benjamin Franklin, 1759. Collection: White House. Image courtesy: Wikimedia Commons |

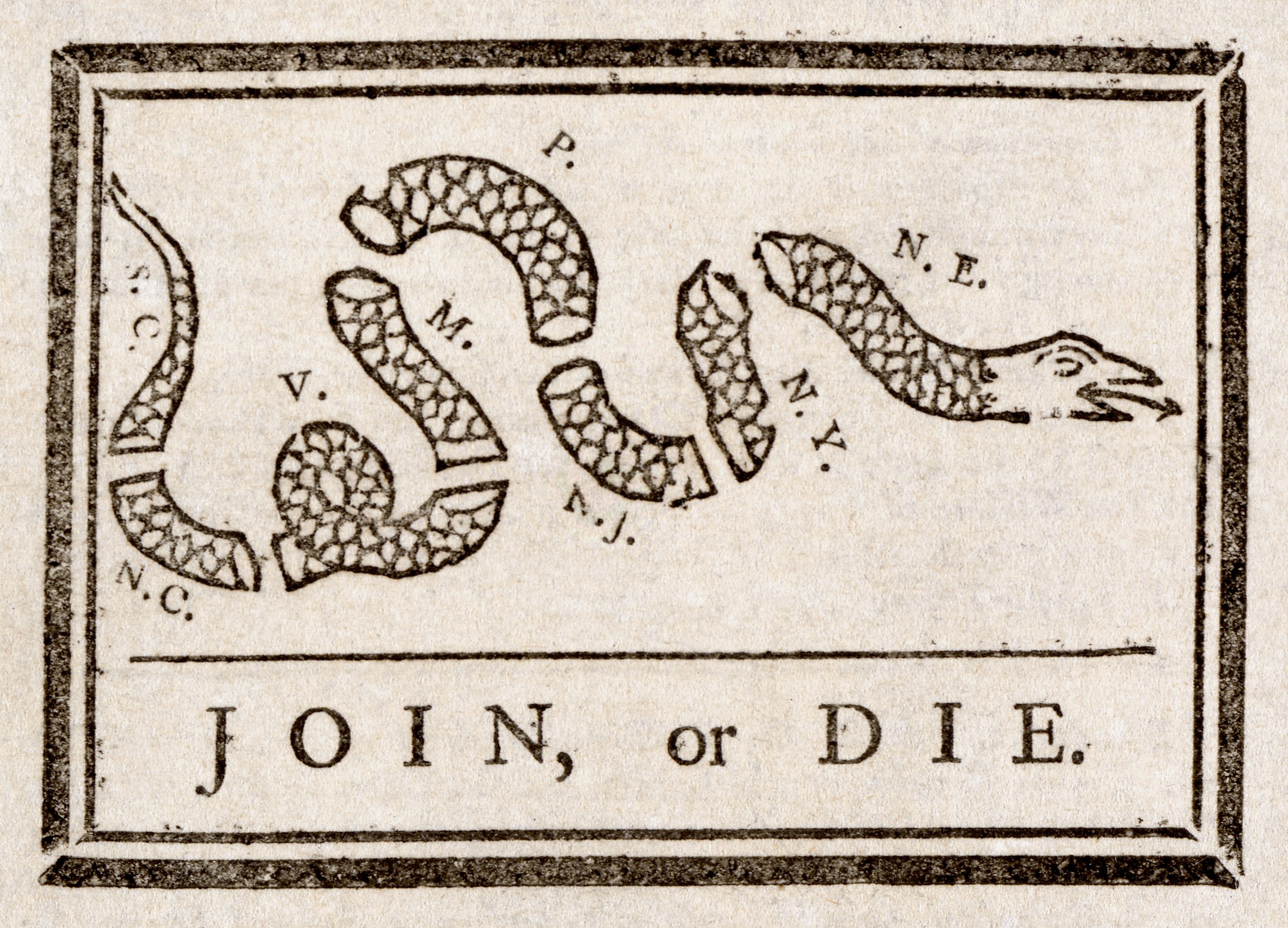

Benjamin Franklin, Join, or Die, 1754.

Image courtesy: Wikimedia Commons

'Join, or Die'In 1754, Benjamin Franklin (1706—1790), a leading author, printer, political theorist, inventor, humorist and statesman from the United States of America, created the iconic ‘Join, or Die’ woodcut, which is considered an early masterpiece of political messaging. The woodcut was designed to unite the American colonies against the French and their Native allies at the start of the French and Indian War, which was a part of the Seven Years’ War that Britain and its allies waged against France and its allies across the colonial world (including in the Indian subcontinent). The snake cut into eight pieces symbolized the British colonies, with each section labelled with the initials of a colony or group of colonies. The snake may have represented regeneration or renewal, since snakes shed their skins, or may have drawn upon a legend of the time, which suggested that a snake that was cut into pieces could come back to life if its parts were assembled before sunset. The cartoon first appeared in The Pennsylvania Gazette and then in other colonial newspapers, and its message hit home. In later years, especially during the colonies’ freedom struggle against the British, the ‘Join or Die’ cartoon resurfaced as a symbol of American unity against their colonial oppressors. |

|

‘Violence is a cleansing force. It frees the native from his inferiority complex and from his despair and inaction; it makes him fearless and restores his self-respect… Violence is man re-creating himself.’ -Frantz Fanon, The Wretched of the Earth ‘(T)he stereotype is the basic building block of all cartoon art’ -Art Spiegelman |

|

Detail from the cover image of a Lance Spearman comic. Image courtesy: African Film and Alchetron |

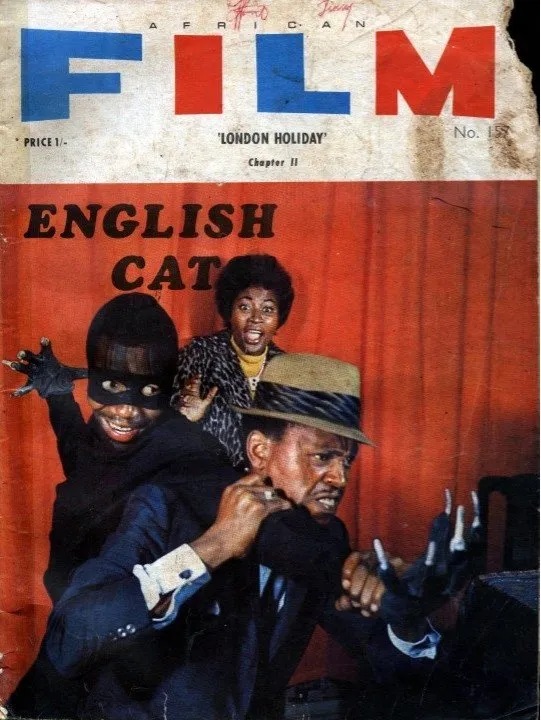

Cover art for an issue of the Lance Spearman comic.

Image courtesy: African Film and Alchteron

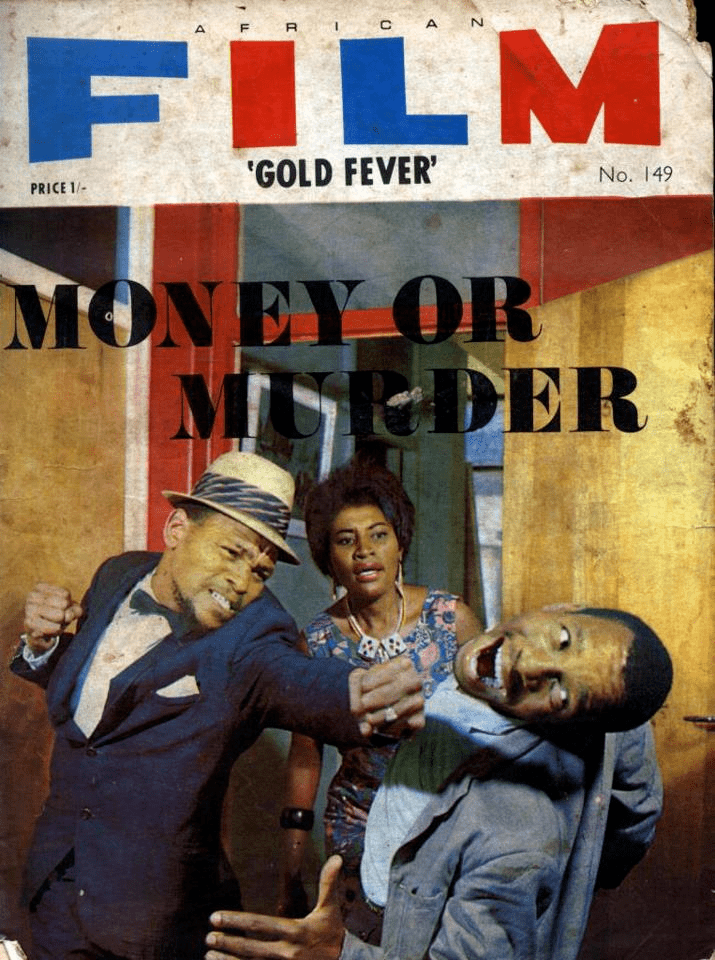

Cover art for an issue of the Lance Spearman comic.

Image courtesy: African Film and Alchteron

Lance SpearmanLance Spearman, also known as ‘The Spear’, is a fictional character created by Drum Publications in 1968. The character was featured in a weekly photo comic called African Film in East and West Africa and Spear Magazine in South Africa. The character was portrayed by Jore Mkwanazi. Lance Spearman is a crime buster who shattered racist stereotypes of the uncivilized, uneducated, and inferior African man. The character had a readership of approximately 20,000 in South Africa, 45,000 in East Africa, and 100,000 in West Africa. Spearman's loyal allies are his agile assistant ‘Sonia’, a twelve-year-old sidekick known as ‘Lemmy’, and a police officer called ‘Captain Victor’. Photo comics are a form of sequential storytelling that uses photographs instead of illustrations for the images, along with the usual conventions of narrative text and word balloons containing dialogue. They are sometimes referred to as photo-novels or, photo-romances. The photographs may be of real people in staged scenes or posed dolls and other toys on sets. The Lance Spearman comics ran until 1972. According to a scholar, ‘In spite of being a medium that is able to convey thrills and pleasures, the photo novel has almost ceased to exist in Africa today.’ |

|

Let the dog bark; the moon shall beam on. -Mohammed Reza Pahlavi, from Gholam Reza Afkhami's The Life and Times of the Shah ‘I had learned that you should always shout louder than your aggressor.’ ― Marjane Satrapi, Persepolis: The Story of a Childhood |

|

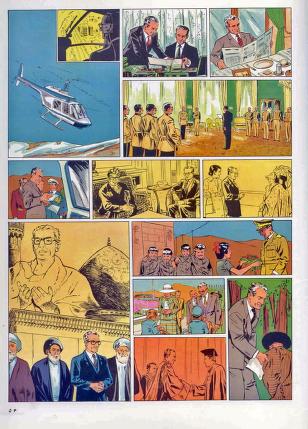

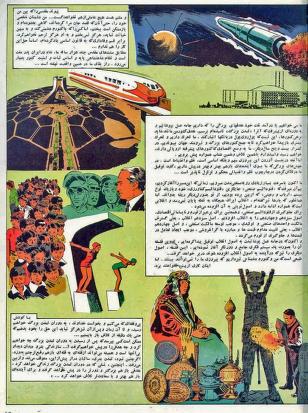

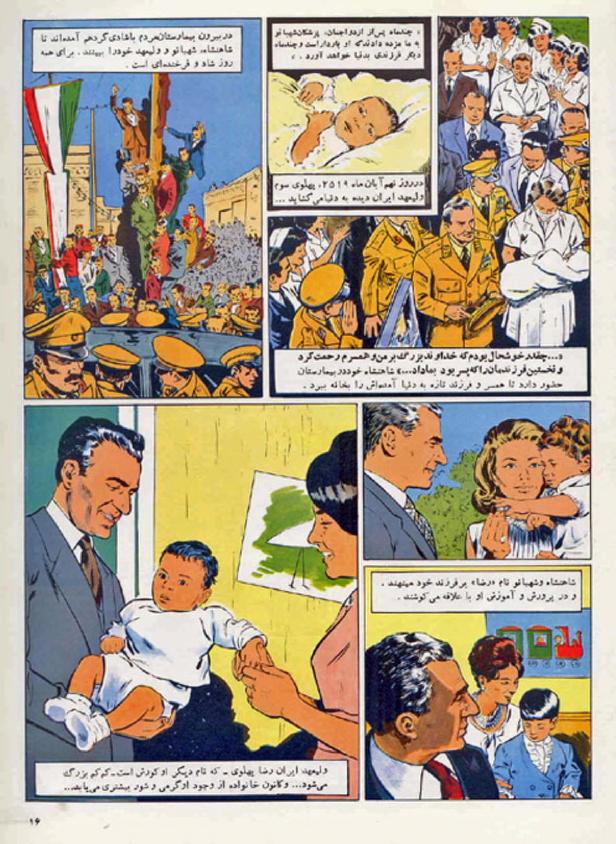

Dino Attanasio, Regained Glory, 1976 Image courtesy: archive.org |

Dino Attanasio, Regained Glory, 1976

Image courtesy: archive.org

Dino Attanasio, Regained Glory, 1976

Image courtesy: archive.org

Dino Attanasio, Regained Glory, 1976

Image courtesy: archive.org

Regained GloryRegained Glory is a comic book illustrated by Dino Attanasio and published in 1974 or 1976, according to some accounts. The comic book is about Mohammad Reza Pahlavi (1919—1980), the last Shah of the Imperial State of Iran, and it praises him and his efforts to ‘modernize’ the country, thereby presenting lavish views of his big infrastructural projects and military strength. The book had a print of 1 million copies at the time, when Iran's population was around 33 million. It is written in Persian. Regained Glory, which appears to have been a commissioned project, reflects the pro-Shah sentiment that existed in Iran at the time, but the project may have been undertaken against the background of his increasingly embattled state during the last years of his rule. He was eventually overthrown by the Iranian Revolution of 1978-79. The novelist and artist-in-exile Marjane Satrapi’s family descended from the Qajar kings who had been deposed by the Shah, making them natural adversaries for the dictator. In her graphic novel, Persepolis, therefore, she presents a very different picture of life in Iran under the Shah, even though she remains ambivalent about the fruits of the revolution that deposed him. |

|

‘None of our republics would be anything if we weren't all together; but we have to create our own history - history of United Yugoslavia, also in the future.’ -Josip Broz Tito Everyone knows that we (comic artists) are ‘gangsters, trampling on the sacred name of art,’ that our works are ‘little pictures for morons,’ that our muse is ‘a mad radioactive mutant.’ —Khikhus, from Jose Alaniz’ Komiks: Comic Art in Russia |

|

Mirko i Slavko Image courtesy: YouTube screengrab |

Desimir Žižović Buin, from Mirko i Slavko.

Image courtesy: Wikimedia Commons

Desimir Žižović Buin, cover art for Mirko i Slavko .

Image courtesy: Wikimedia Commons

Mirko and SlavkoMirko i Slavko was a Yugoslav comic book series about two Partisan couriers, running from 1958 to 1979. The comic was created by Desimir Žižović Buin and was aimed at the youth as propaganda for resistance during the Second World War. The comic was reputedly modelled after Žižović's son, and the names Mirko and Slavko were chosen because they were common in all parts of erstwhile Yugoslavia. In the late 1950s, ‘Dečje novine’, Yugoslavia’s largest comic publishing house based in Gornji Milanovac, started publishing a series of historical comics entitled ‘Nikad robom’ (Never a Slave), which featured heroic stories from the history of the South Slavic people. Mirko i Slavko was a part of that series, eventually upstaging all the other comics from the Nikad robom series. The editors decided to print Mirko i Slavko in 120,000 copies, but soon found out that the demand for it was even larger. The comic celebrated the publication of the 500th issue in 1975, but by this time, the comic's popularity had mostly declined. The comic was initially written by Žižović himself and later by various writers. By 1992, the Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia had dissolved into a variety of smaller, successor states. |

|

Comics have been used to reduce individual characters into representations of cultural ideas, allowing characters to become powerful representations of nationalism or the search for societal stability. Due to their glossing of subtlety or complexity in socio-cultural relations they have been consistent in creating clearly identifiable mass-produced images for communities, giving collective desires visible shape and strong narratives. In India, Amar Chitra Katha can be said to have played a similar role of reviving interest and confidence in Indian mythological and folk narratives when the market was largely unrepresentative of Indian or indeed any non-western comic products. With this early attempt to forge cultural confidence, however, came other problems as described by Par Christophe Dony: ‘…the series has often been criticized for presenting a very conservative, simplified, and pro-masculine version of India’s cultural heritage… many stories emanating from the Amar Chitra Katha comics have employed narrative and visual strategies that are at odds with some of the tropes traditionally embraced and/or promoted by postcolonial studies and scholars, namely hybridity, multiculturalism, and resistance. Thus, the Amar Chitra Katha series has to some extent distanced itself from some of the social, historical, and cultural remnants of the colonial regime and it has carved a niche for indigenous comics in India. However, it has simultaneously produced a very conservative historiography and supported a nationalist agenda that was arguably influenced by the former colonial rule.’ It became the task of more conscious comic book artists to break through this bind of revival and recovery—in a process that is still ongoing with artists across the decolonial world. |

|

Detail from a poster for Raj comics. Illustrated by Pratap Mullick Image courtesy: Wikimedia Commons |