The City in Design: City as a Museum, Kolkata, 2023 Part IIUpasana Das January 01, 2024 Bengal has a rich tradition of integrating art and aesthetics into everyday life – be it the alpona art on our doorsteps or the brightly-painted soras that we see around us during lokkhi pujo. Languid eyes, once painted by Jamini Roy, once embedded into the popular culture of the city, peep at us from restaurant menus and pujo pandals. Continuing on our journey to discover Bengal's design histories, in the second part of this photo-essay, we recount the other programmes undertaken for ‘The City as a Museum’, Kolkata, 2023. |

|

|

Keyabat MeyeThe queer-feminist theatre troupe 'Samuho' performed the twentieth century morality play ‘Keyabat Meye’ (Wow Woman!) which parodied the figure of the new woman – who was educated and had the freedom to move freely in society. A large section of Bengali society saw these initiatives for women’s education, and the ways in which they could exert their free will, as going against their culture – so the satirical plays were devised to express their displeasure. In the rendition by Samuho, Jnanadnandini Debi devised the Brahmika style of draping a sari, Nati Binodini rued her theatrical history as written by men and Indira Debi and Pramatha Choudhuri exchanged letters across seas. The performers used the entire space of North Kolkata’s Barrister Babu’s house, as it is now known, to present various sections of the play, creating spaces of intimacy and engagement. |

|

‘Due to her natural ability, she (Jnanadanandini) was even requested for help when plays were staged at home…Jnanadanandini also began the practice of wearing petticoats, chemises, blouses and jackets with sarees. We have to remember that other Brahmikas had been pondering on an appropriate dress for going out-of-doors.’ |

|

|

Yellow, Blue and Art on the MoveOn the seventh day of the festival, we gathered at the Esplanade Bus depot in central Kolkata to observe something that we see every day, but do not look closely at – bus art. The artist Sumantra Mukherjee introduced us to the concept of vehicular art, which takes the form of artistic interventions on government stipulated yellow and blue coloured buses that ply the city. city. We were also joined by the bus artist Bazlur Rahaman, who explained the concepts behind various motifs on the bus and the different ways in which drivers personalise their vehicles, almost as if it were their own room. He demonstrated this by painting the word ‘Pilot’, which is typically written under the driver’s window, and transforming each letter into miniature figures of umbrellas, hand fans and cricket balls. |

|

‘The new colour guidelines that enforce visual homogeneity discourage artistic flourishes and improvisation... This recent drive... is a wish to erase ‘difference’, those many signs of our backwardness and unmodernity.’ |

|

|

In Search of SandeshStanding before the Rajbati building on Chitpur road, one can see the entire process of transformation of the sandesh, from milk to sweetmeat. As cans of milk were wheeled away on bicycles, the sharp hammering of the mould-maker’s chisel brought us to workshops filled with fish, rose, chandrapuli and modak-shaped woodcuts which would ultimately shape the sweet. From chaana-making stores, we arrived at the famed sweet shops of Makhan Lal Das and Nalin Chandra where they mixed the chhana (cottage cheese) with syrup and pressed the mixture against the solid wood, now tinted black with age, as the jolbhora design emerged on soft chhana. |

|

‘What makes Bengali sweets different from those of the rest of the country is that chhana is used as the main ingredient in them, while most of the rest of India relies on khoya, a milk solid prepared by boiling full-cream milk till it condenses to a thick paste, which is then cooled down to a hard mass. Bengali sweets are more perishable because chhana is soft and full of moisture; the sugar in them actually plays the role of a preservative.’ |

|

|

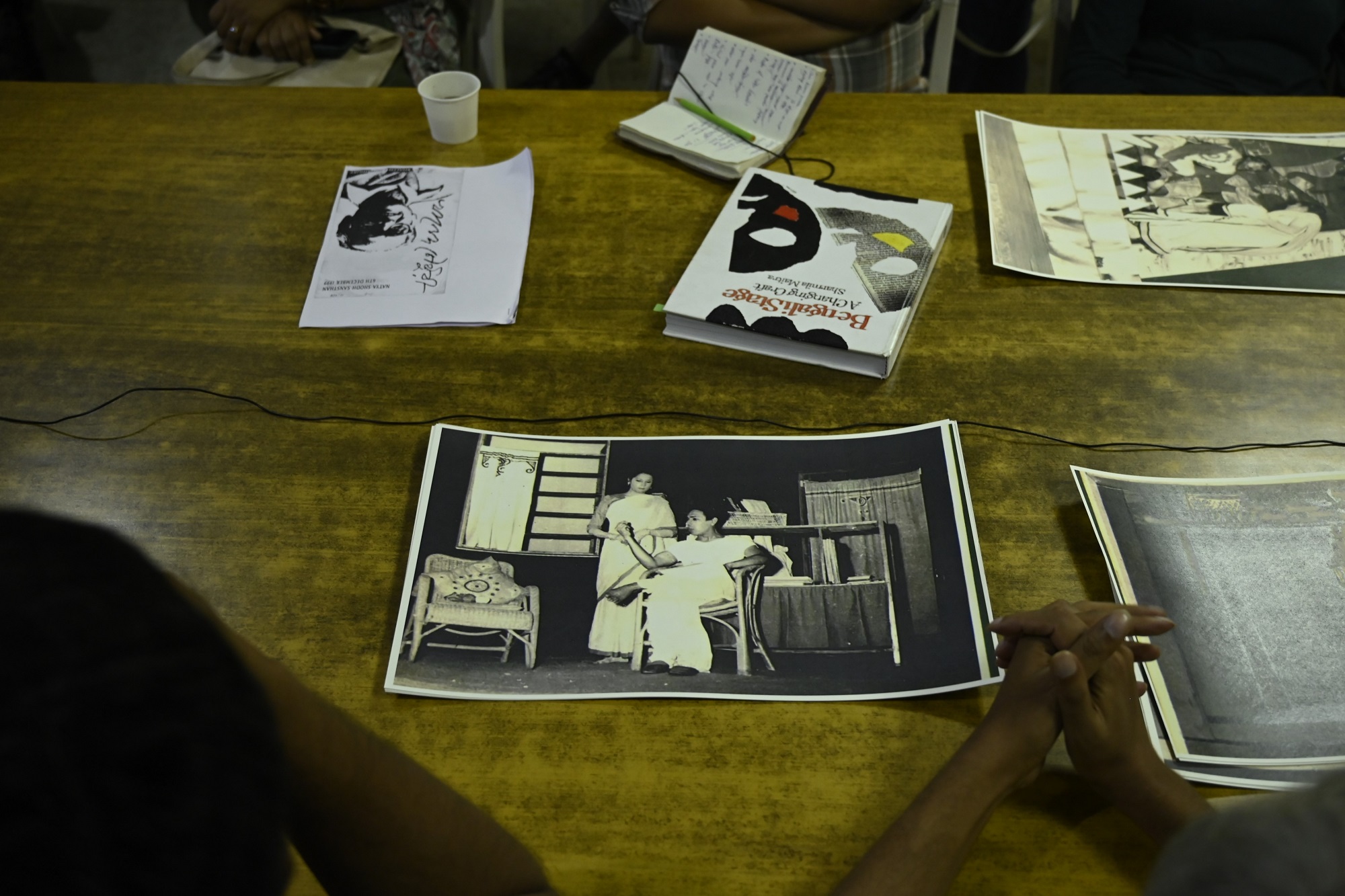

Mise-en-StageModern artists in Bengal like Jamini Roy have been instrumental in designing sets for theatre and performance. At the theatre archive at Natyashodh Sansthan, Trina Nileena Banerjee spoke about how set design is often an ignored aspect of theatre criticism, even though it adds another framework of interpretation for the play and traced the works of significant set designers in Bengal theatre—who drew from the work of Bengal modernists like Chittaprosad. |

|

‘Bishorjon’ (Sacrifice) had a very interesting set – the production was directed later by Sumon Mukhopadhyay. The play is about Kali and sacrifice – devotion to the goddess and a rejection of the blood sacrifice involved. The whole play is dominated by the specter of the goddess – when the curtains open, one sees these two feet and an inclined platform which reaches downstage to the audience. Most of the characters as they are speaking, are balancing themselves on this impossible-to-stand ground. Characters who are unsure of themselves are scrambling to steady themselves on this ground – climbing up and down the platform like animals, which is what the idea is – humans become animal-like when they celebrate violence.’ |

|

|

Sora BrittantoOn the penultimate day of the festival, we travelled to Taherpur to learn about the practices and genealogies of sora-making with artists Ratan Paul and Gopal Paul. The artist-writer Dipankar Parui, who has been researching the sora for many years, explained how styles of storytelling through particular motifs have carried on through generations of sora makers and how they have changed depending on the socio-political circumstances surrounding them, like the partition of 1947. The artists then demonstrated how they painted various kinds of soras, and the division of labour in finishing different segments like jewellery or fine lines. The participants painted their own versions of the sora, taking inspiration from the traditional line-drawing in soras, pairing it with themes from their own lives. |

|

‘Composition-wise, soras have been divided into two or three portions, which are then filled with gods or people. Taherpur soras have two divisions – sometimes three. Their soras are tinted brighter, and delight us with their intricate designs. Taherpur’s sora designs have an element of patachitra in them.’ |

|

|

Gab-Sur-KinnarThe third edition of ‘The City as a Museum’ came to an end with a tabla concert at the historic building of Jorasanko Thakurbari. Curated by the sitarist Subhranil Sarkar, tabla artists Rohen Bose and Asif Khan spoke about the history and nuances of their own gharanas, namely the Benares and the Farrukhabad gharanas respectively – focusing on tabla-making, patronage, courtly practices and instrument design as an evolving practice. This was accompanied by a short film where Shyamal Das demonstrated the different stages of tabla making in his workshop in Kolkata. The concert came to an end with Bose and Khan coming together in a ‘sangat’ with Alla Rakha Kalawant on the sarangi. |

|

|