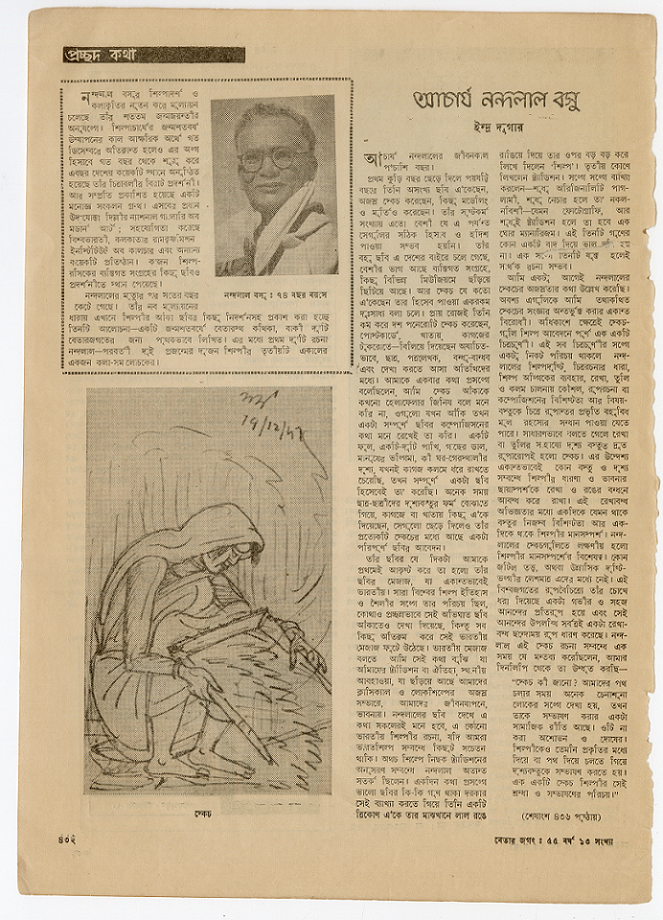

The Art of Letters: Nandalal Bose & Indra Dugar's Friendship

The Art of Letters: Nandalal Bose & Indra Dugar's Friendship

The Art of Letters: Nandalal Bose & Indra Dugar's Friendship

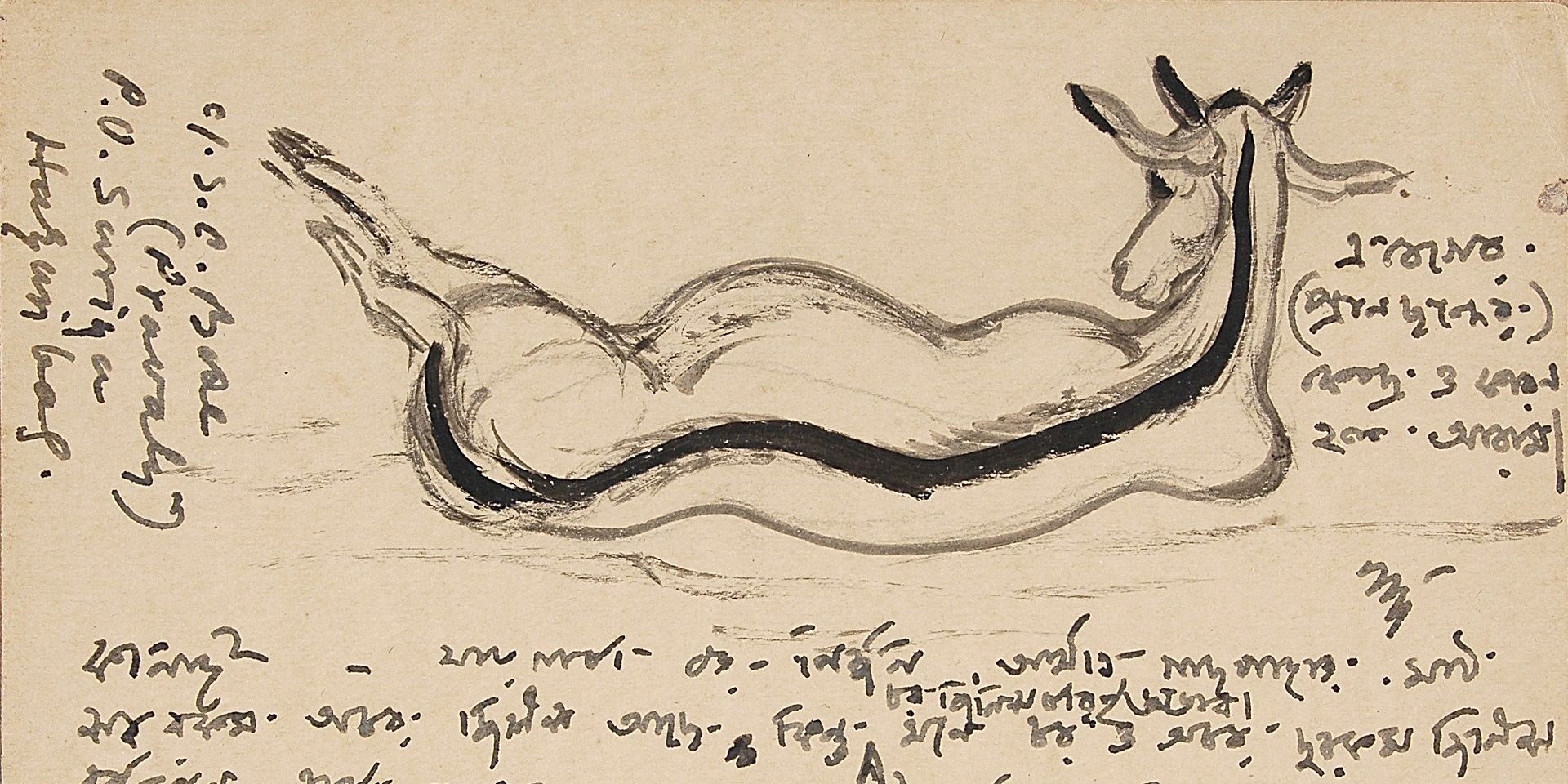

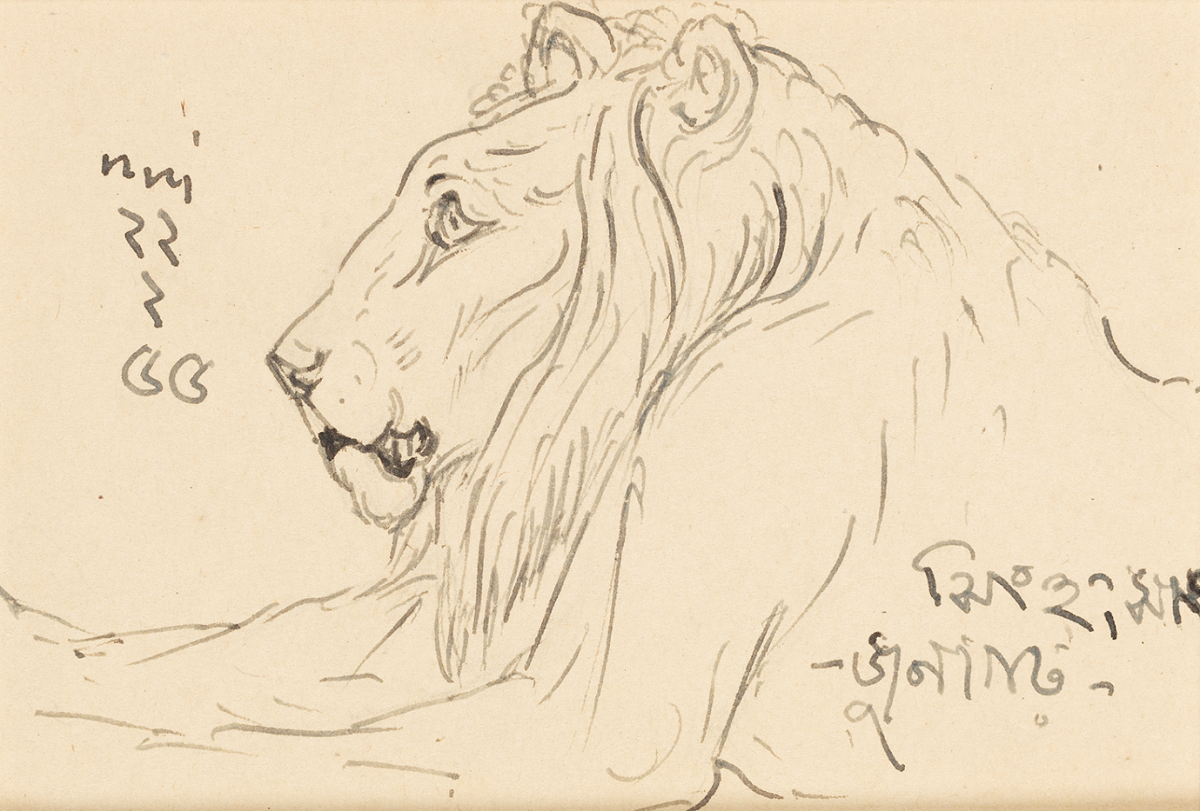

Nandalal Bose, Untitled (detail), 1954, Ink on card. Collection: DAG

Exchanging letters has long been essential for fostering growth within the artistic community, enabling members to share ideas, emotions, express bonds, exchange techniques, and provide critique across generations. For artists like Nandalal Bose this form of communication was not only a means of staying connected but also a vital element in one's artistic development. In this article we will take a closer look at the ‘Mastermoshai’s’ (the Master's) friendship with Indra Dugar, through the medium of letters and postcards.

|

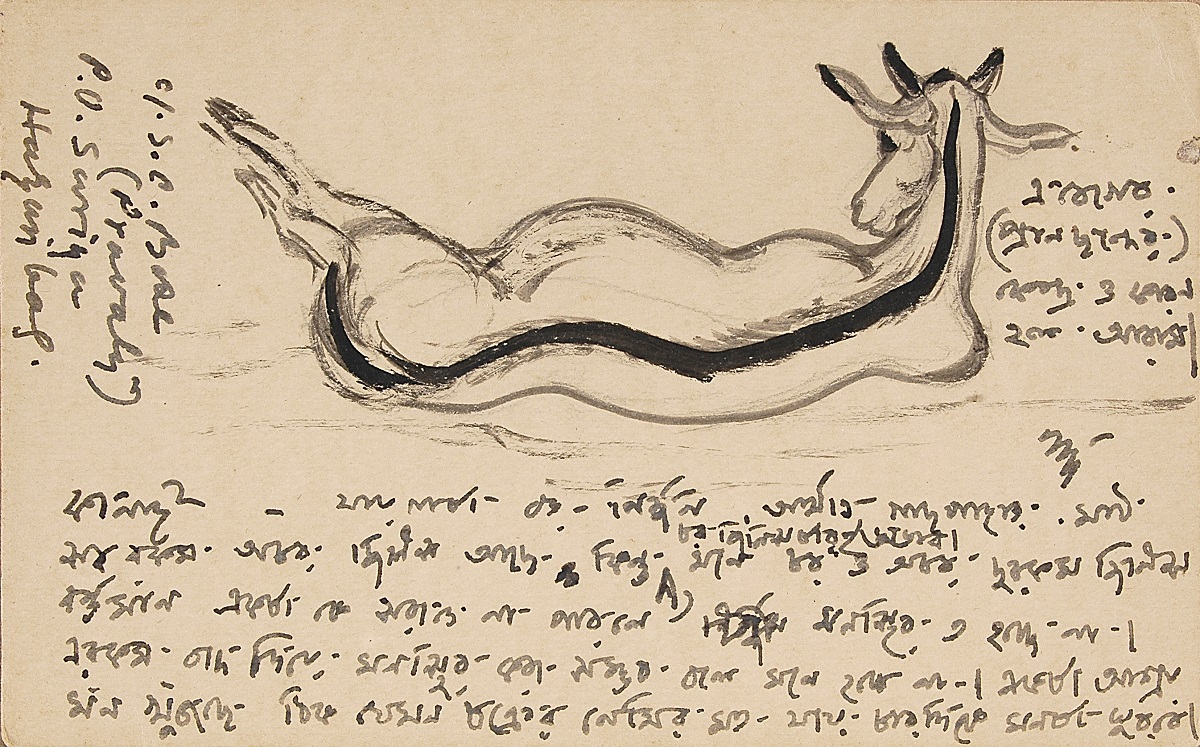

Nandalal Bose, Sketching in the Night / Tourer Kotha, 1953, Ink on postcard, 2.7 x 3.2 in. Collection: DAG |

Since early 1916, Bose's arrival in Santiniketan marked the beginning of his consistent engagement in correspondence, which he continued throughout his life to further his creative goals. His notable mentors, Abanindranath Tagore and Rabindranath Tagore, exchanged many letters with him, significantly shaping the evolution of his artistic practice.

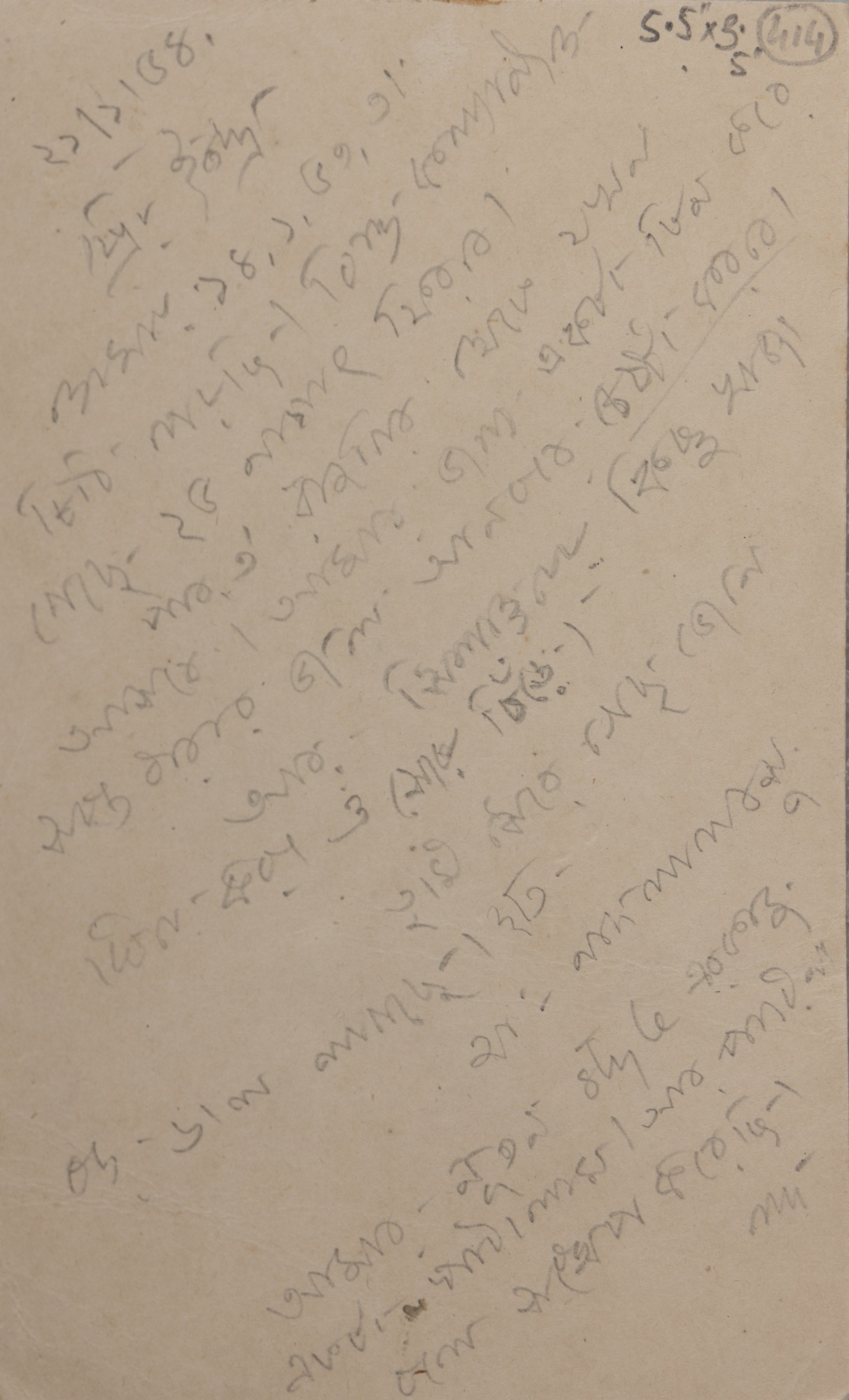

Nandalal Bose, Untitled, 1954, Ink on card. Collection: DAG

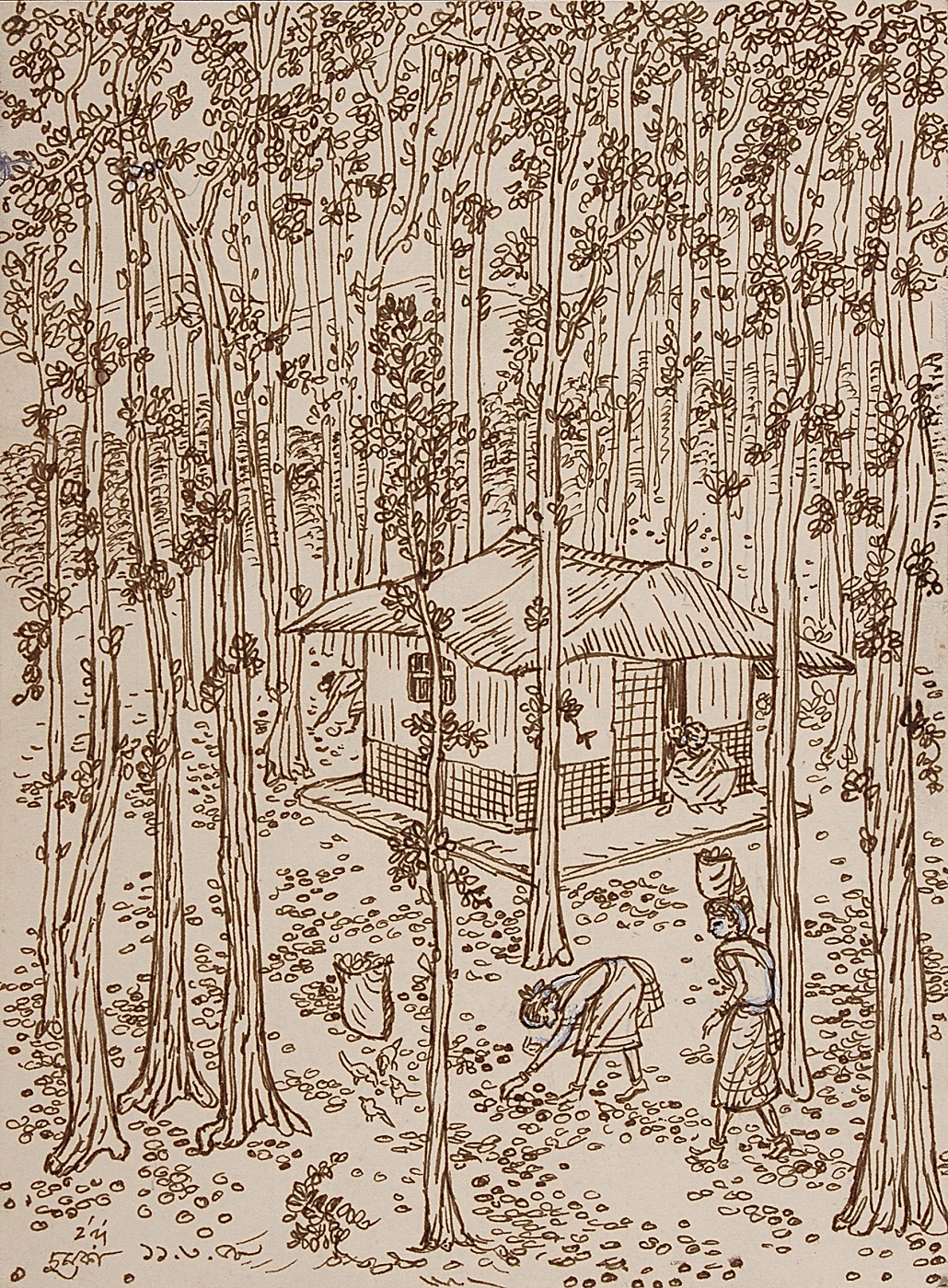

This practice can be seen not just as a legacy he carried but as a profound spiritual pursuit—an endeavour to understand, explore, and document the passage of time and the essence of life itself. As the artist A. Ramachandran, a former student at Santiniketan, would write, ‘He made quick graphic impressions, often simplifying them to a just a few lines... he sought to understand the inherent structure of what he is seeing. At times he recorded objects in a more analytical way, while at others he transformed them into visual code of pattern. The more he sketched as a day to day exercise, the more clear and purposeful his idea of art and teaching became.’

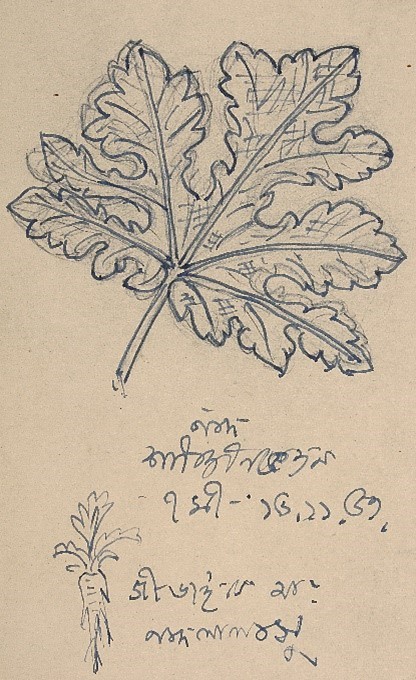

Nandalal always carried the tools of his trade with him, in order to capture his surroundings or visualise a thought. A bottle of Chinese ink along with brushes, pens, postcards, and scrap paper were permanently placed in his satchel. The number of postcards he produced during his lifetime present a visual diary of his travels and sensory experiences. He always carried a stack of small cards with him, on which he would both draw and write. He would draw or paint his immediate surroundings and the everyday world around him, but often, would sketch out potential ideas for various paintings and murals that he was working on. ‘His self-devised practice of constant sketching of different subjects in various styles and media was his way of finding the divine unity, which he called life rhythm, that pervade the multiplicity of all things in nature through a joyful act of leela (creative play),’ as Supratik Bose writes.

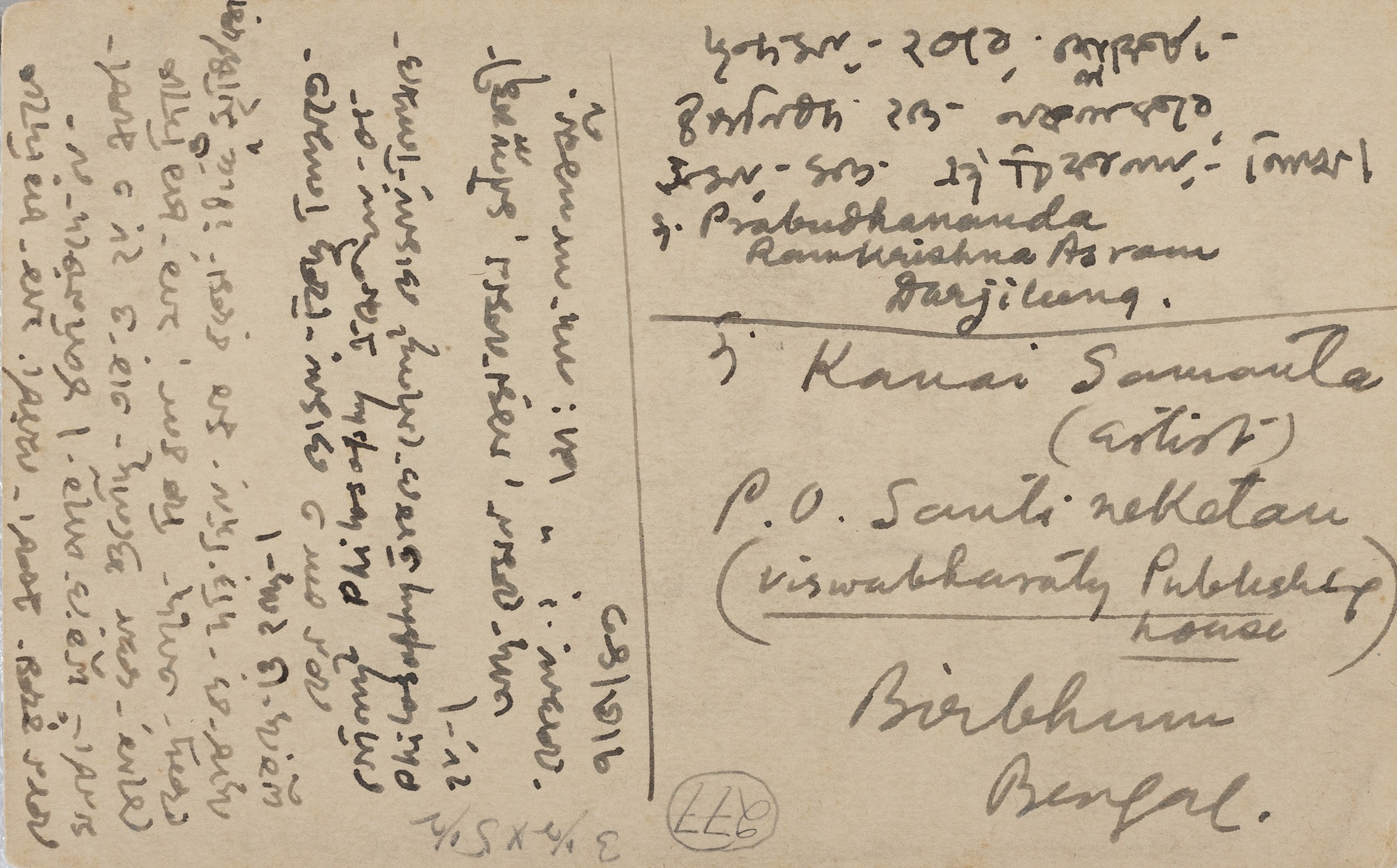

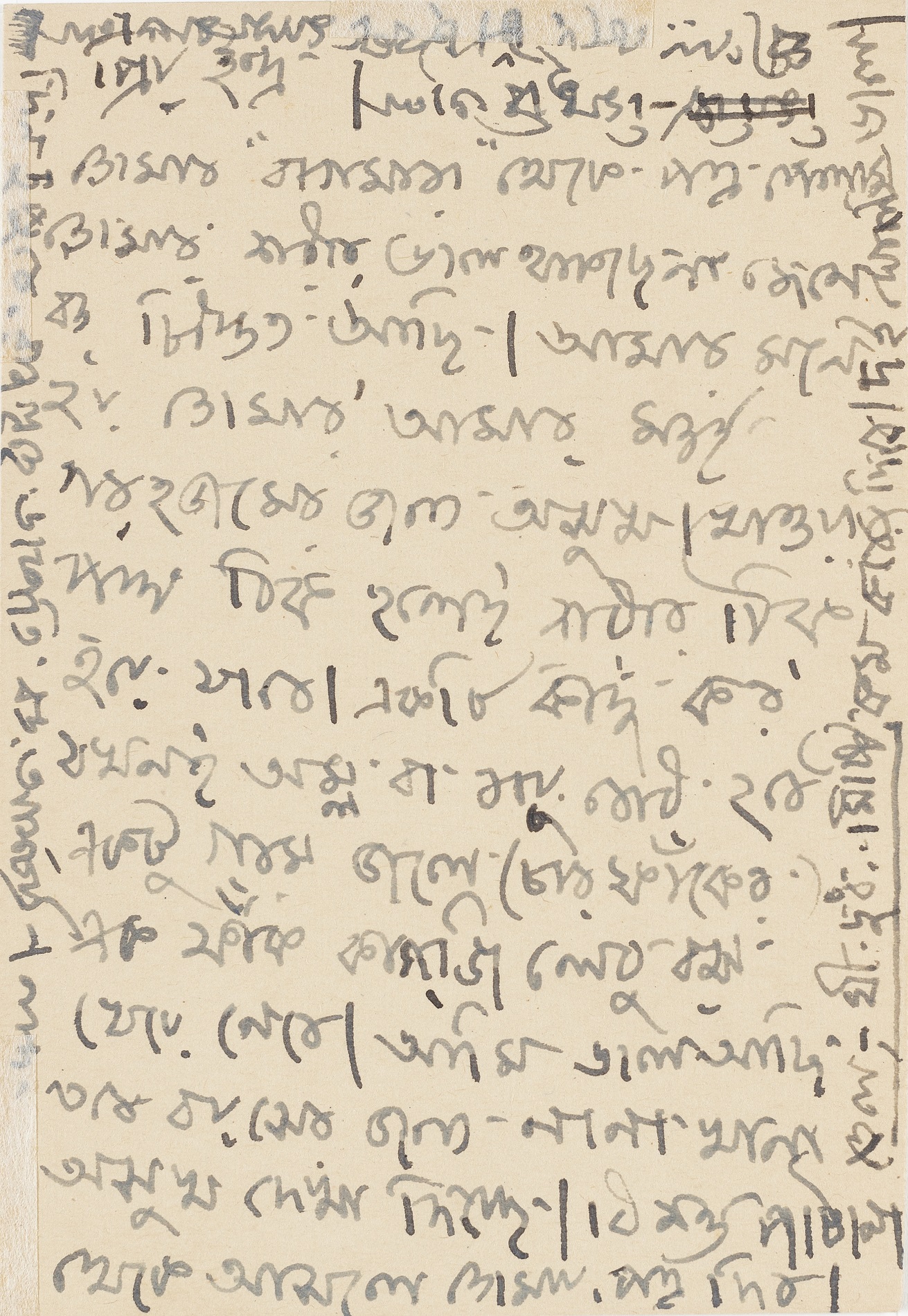

Nandalal Bose, Ink inscription on card, 1954, 3.5 x 5.5 in. Collection: DAG

In his letters, Bose would often use simple to complex metaphors and frequently resort to humour (using visual puns, for instance) in his approach to drawing and writing. For instance, his postcard to a certain ‘Muljibhai’ was accompanied by the drawing of a radish, which is called ‘Mulo’ in Bengali (and ‘bhai’ means brother). At other times he recorded poetic descriptions of landscapes that touched him, employing unusual metaphors and images.

|

Nandalal Bose, Untitled, 1953, Ink on card, 5.5 X 3.2 in. Collection: DAG |

Introducing Indra Dugar

Born in 1918 in Jiaganj in Murshidabad, West Bengal, Indra Dugar’s family belonged to the Jain community that had migrated from Rajasthan. The artistic ambience from his childhood and the role of his father Hirachand Dugar (who was a graduate of the first batch of students graduating from the newly formed Kala Bhavana, Santiniketan) influenced him to take up art professionally.

He would later write, ‘My father, Hira Chand, was the melodious music. I am just a very faint distant echo [...] He is a key that would, as it were, open the small lock of my humble treasure chest.’

Though he was self-trained, his first mentor was Nandalal Bose who was also his father’s guru (teacher and mentor). Bose's influence and mentorship deeply influenced Dugar’s artistic practice which enriched him spiritually too. Bose was also glad to find such a masterful exponent of art in Indra, and he said, ’It has given me great pleasure to discover in the son of an artist father quite good promise of another artist. From what I have been able to judge of Sriman Indra's works, I consider he has in him real artistic talents.’

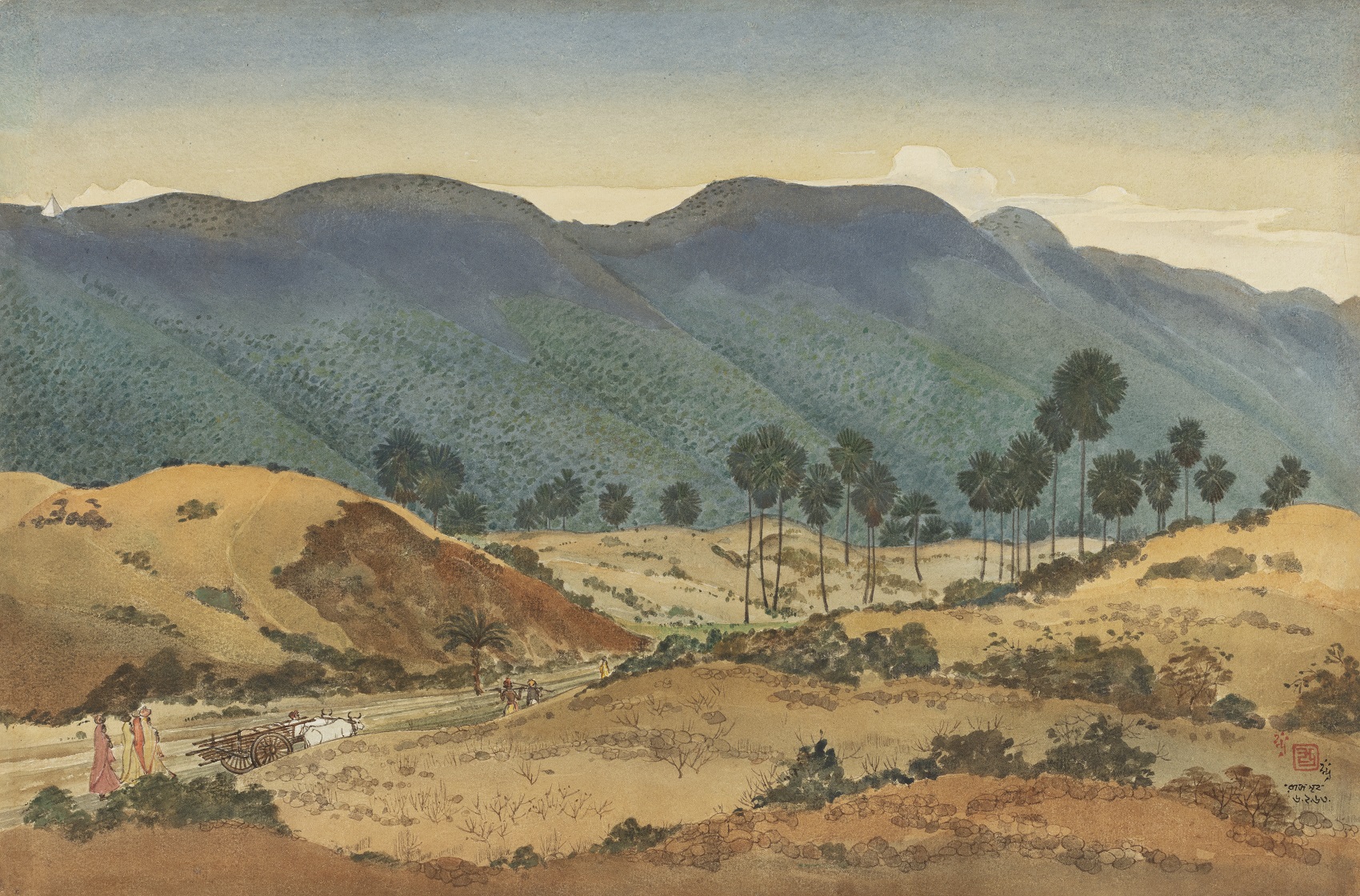

Hirachand Dugar, The Village Bijbehara from Table Land, Kashmir, 1922, Watercolour on paper, 7.0 X 10.2 in. Collection: DAG

Practice of sketching and its relationship with travel

Nandalal Bose once wrote to Indra Dugar in one of his letters: ‘Do you know what a sketch is? In our daily life, we encounter people, and addressing them is a part of our social culture. If we do not, it is regarded as ill-mannered. Similarly, for an artist, exploring things through nature and existence and addressing those visuals of daily life is a sketch.’

|

Acharya Nandalal Bose by Indra Dugar (Betar Jogot, p.432 1955, Edition 13), Print on paper. Collection: DAG Archives |

Drawing holds a pivotal place in Nandalal Bose’s artistic practice, particularly his emphasis on line drawing. The rhythmic flow of Bose's lines not only signifies movement but also embodies balance—a concept of equilibrium and order that transcends mere representation. This quality serves as a medium for philosophical inquiry and spiritual reflection, suggesting a contemplation on the delicate interplay of life's forces, where opposing elements harmoniously coexist. Bose's exploration of the 'rhythm' of life is inspired by Rabindranath Tagore, who, in a letter to Bose, expressed:

‘O beauty, Open your door

Bring the dream of heaven in the eye of the earth

Let the formless express itself in the limit of form

Showing the dance of souls in the lines of drawing.’

This conceptual approach to drawing and sketching influenced Indra Dugar in his art practice. Both Dugar and Bose extensively documented and sketched their surroundings in their daily lives. Dugar painted en plein air during his travels across the country and visits to his hometown of Jiganj. Similarly, Bose also sketched and painted during his travels throughout India. Occasionally, they visited the same locations at various times and captured similar landscapes; one notable instance was their trip to Rajgir in Bihar.

Nandalal Bose, Untitled (Rajgir), 1948, Ink on card, 3.7 X 5.7 in. Collection: DAG

Indra Dugar, Mountain Clouds (Rajgir), 1953, Ink on paper, 10.2 x 14.5 in. Collection: DAG

Their travels served not only to hone their aesthetic skills but also to document the passage of time and changes in their surroundings. Both artists infused their works with a pan-Asian essence, drawing inspiration from the Swadeshi movement and utilising materials sourced from India and Asia as their primary mediums of expression. Emphasising the concept of 'Rhythm,' as discussed earlier, their artworks exhibit a freedom of brushstrokes yet maintain a balanced harmony, clearly influenced by Japanese and Chinese calligraphy.

The theme of nationalism is prominently displayed in Bose and Dugar's artworks. Bose played a significant role in fostering nationalist sentiments in Dugar. During one conversation, when Dugar expressed interest in exploring European art and culture, Bose questioned him about his travels within India, emphasising the importance of understanding one's homeland and heritage before venturing abroad. While Dugar drew inspiration from Bose's ideologies, he creatively incorporated and adapted these ideas into his own artistic practice, thus establishing his own identity. His use of watercolour wash painting, especially in landscapes, exhibits a distinct and delicate quality that diverges notably from the techniques favoured by the Bengal School artists of his time. This approach lends his landscapes a unique and picturesque aesthetic.

Indra Dugar, Through Green Hills of Rajgir, 1963, Watercolour wash on Whatman paper, 11.0 x 16.5 in. Collection: DAG

Both Nandalal and Dugar explored the art of line drawing in their works, experimenting with various techniques to capture a linear and sensitive quality that emphasises the concept of rhythm and human existence. In South Asia, where higher temperatures and abundant sunlight prevail year-round compared to other regions, the contour lines of objects appear sharper and more pronounced to the human eye under bright sunlight, while their volume becomes more apparent in lower intensity light.

Indra Dugar, Dusty Dawn (Rajgir), 1966, Watercolour on paper, 14.7 x 22.5 in. Collection: DAG

This scientific distinction in light perception significantly influences art. Traditional paintings from India and Asia often prioritise line drawing, leveraging the clarity and defined edges visible in bright sunlight as essential elements of artistic representation in these cultural contexts. Their mastery of lines not only distinguishes their individual artistic approaches but also offers profound insights into their perspectives on human nature and perception.

|

Indra Dugar, Untitled, 1958, Ink on paper, 6.0 x 4.5 in. Collection: DAG |

Elements of Communication

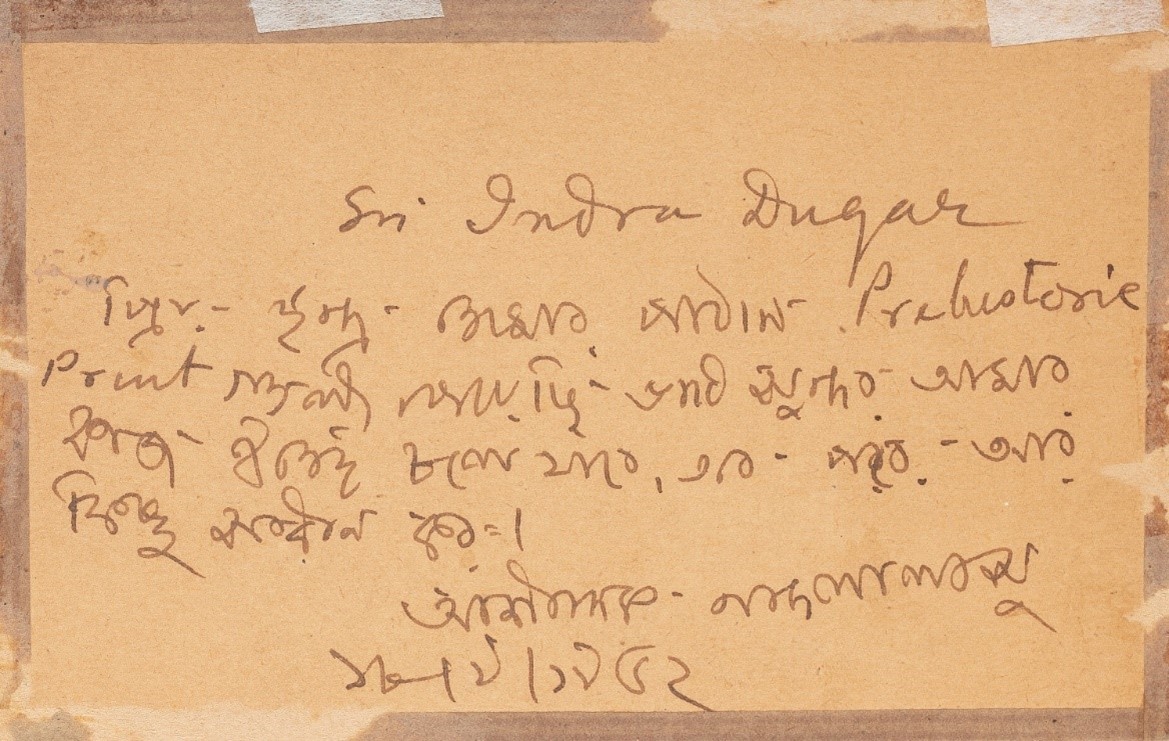

The exchange of letters between Bose and Indra Dugar illustrates a supportive mentorship that fostered growth in their respective artistic practices. Their correspondence provides insight into how their mutual assistance and encouragement played a pivotal role in shaping their development as artists, with one often sending back samples of creative artwork to the other for study and inspiration.

In one of the letters dated 18 September 1952, Bose writes, ‘Dear Indra, I have received your Prehistoric prints (...) they are beautiful. As of now these prints will work for me but do search more in the future.’

Nandalal Bose, Ink on paper, 1952, 3.5 x 5.2 in. Collection: DAG

Nandalal Bose, Untitled, 1952, Ink and watercolour on tinted paper, 3.5 x 5.2 in. Collection: DAG

Besides Bose's mentorship of Indra, their correspondence reflects a sense of mutual support that convey a deep sense of care and affection for each other. In one such letter, Bose writes to Dugar, acknowledging receipt of Dugar's letter from Bagmara (close to Jiaganj, in present-day Bangladesh), in which the latter had expressed concern about Bose's health, particularly issues related to indigestion. Dugar recommended drinking lukewarm water with lime juice as a remedy. Bose also mentions his own health challenges stemming from age-related complications. In turn, Bose recommended to Indra Dugar that he should reduce his consumption of oils, ghee, and sweets, and instead opt for fresh butter, rock candy (mishri), and curd as healthier alternatives.

Nandalal Bose, Untitled (recto), Ink on card, 1955, 3.0 x 4.5 in. Collection: DAG

|

Nandalal Bose, Ink inscription on paper (verso), 1955, 3.0 x 4.5 in. Collection: DAG |

In another letter from 1953, Bose shares his new mode of art practice with Indra Dugar, writing,

’Dear Indra,

I have received your letter on 14.01.53, Bishu is in Kalyani and will return on 25th approx. If possible, please bring tin cased 'Sapta-dhara' (seven stream's) water for me. Also, bring some tin cans of sweets and flattened rice. I am very glad to hear that you have recovered. Aa: Nandalal Bose, here am sending you one of my new style works. Cannot do much these days so making it short and minimal.’

As the last line suggests, Bose was unwell at the time. Despite his illness at the age of seventy-two, he demonstrated remarkable dedication and passion for his art, exploring a new mode of expression akin to Zen artists. He worked with spontaneity, transforming existing shapes with subtle adjustments into significant forms.

|

Nandalal Bose, Maa Chele Kole Dariye Ache (Mother standing with her child) (recto), 1954, Collage and ink on card, 5.5 x 3.5 in. Collection: DAG |

|

Nandalal Bose, Graphite inscription on paper (verso), 1955, 5.5 x 3.5 in. Collection: DAG |

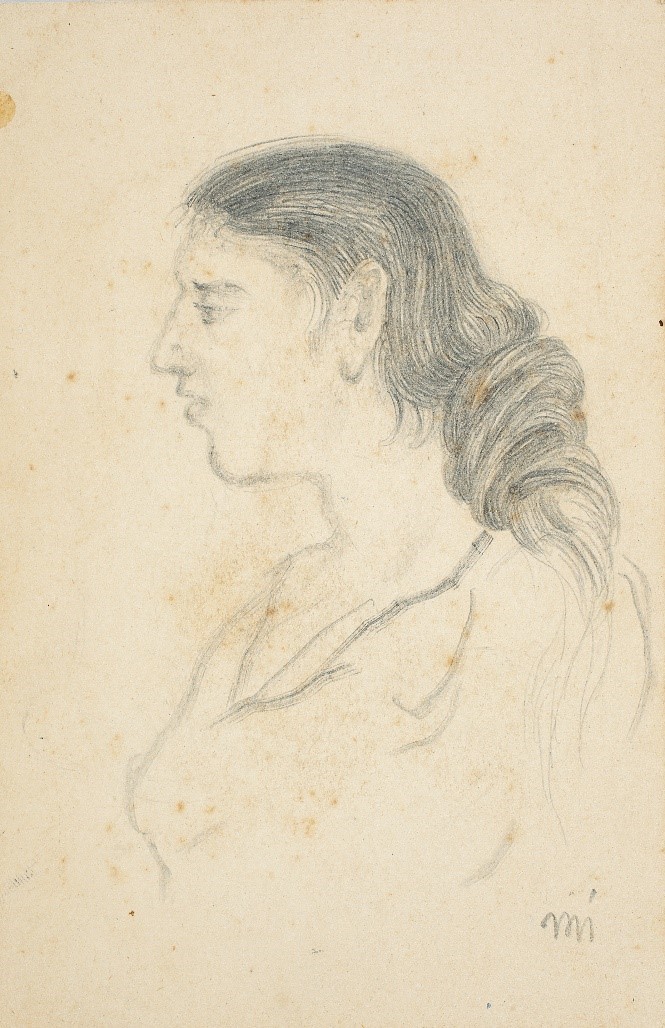

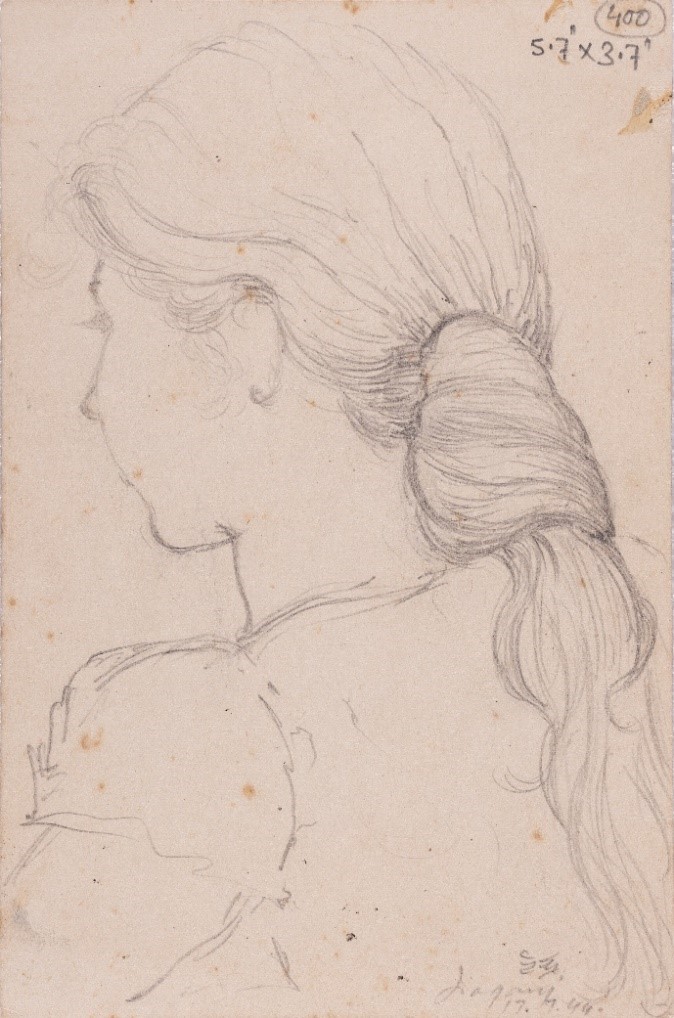

Their collaborative practice of drawing and painting over correspondence occasionally led them to share a mutual fondness for particular places and figures which they would both attempt to draw in tandem. In a postcard dated April 17 1944, from Jiaganj, they depicted a woman’s head on both sides of a postcard. Bose rendered the head in ink on the front (recto) with his signature, while Dugar used graphite on the back (verso), signing, dating, and inscribing the drawing.

|

Nandalal Bose (recto), Untitled, 1944, Ink on card, 6.0 x 3.7 in. Collection: DAG |

|

Indra Dugar (verso), Untitled, 1944, Graphite on card, 6.0 x 3.7 in. Collection: DAG |

The bond between Nandalal Bose and Indra Dugar transcended the conventional teacher-student dynamic, blossoming into a deep and enduring friendship. Their correspondence, rich in artistic dialogue and personal sharing, not only nourished their creative spirits but also supported their emotional well-being. This unique synergy stimulated innovation in their art, blending mentorship with genuine camaraderie. Their letters went beyond mere exchange of ideas; they served as vital threads that intertwined their lives and artistic journeys, fostering mutual growth and discovery.

Reflecting on their remarkable relationship, it makes us wonder: In today's world of instant yet often superficial communication (which includes the sharing of images), how can we retain that element of chance, playfulness and discovery?