|

Argot Term of the Month: The StereoscopeThe Editorial Team October 01, 2023 How did the stereoscope, and the three dimensional images it produced, promote tourism and techniques of image reception? From becoming a popular aid for creating tourist-friendly images of exotic locales to being used to enhance the spectacle of landmark imperial events like the Delhi Durbar, the stereoscope, still in use, has come a long way. In this article we will try to highlight some of the important aspects of this term as part of our recurring series, Argot, where we seek to demystify some of the major ideas from the world of art. |

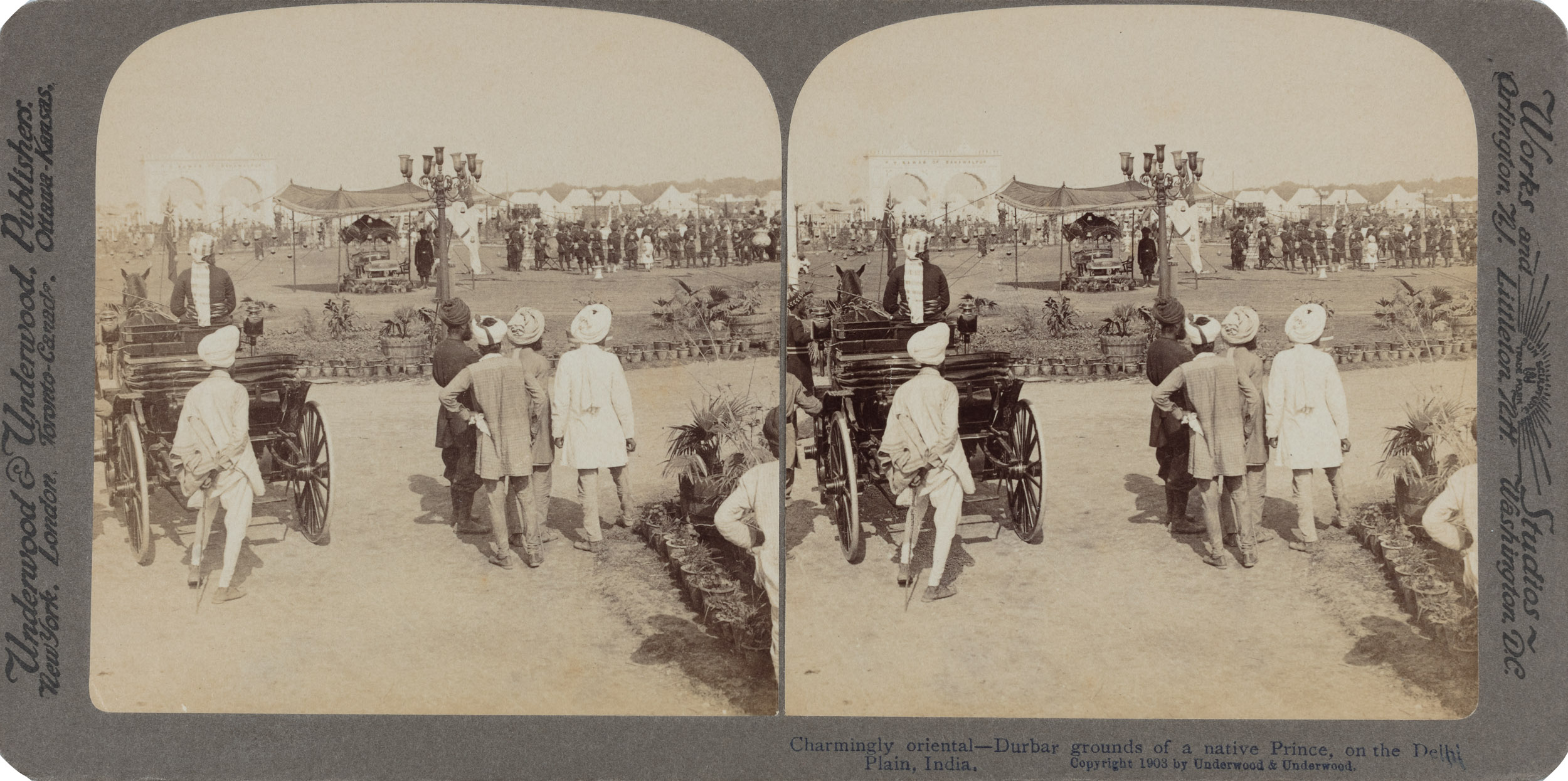

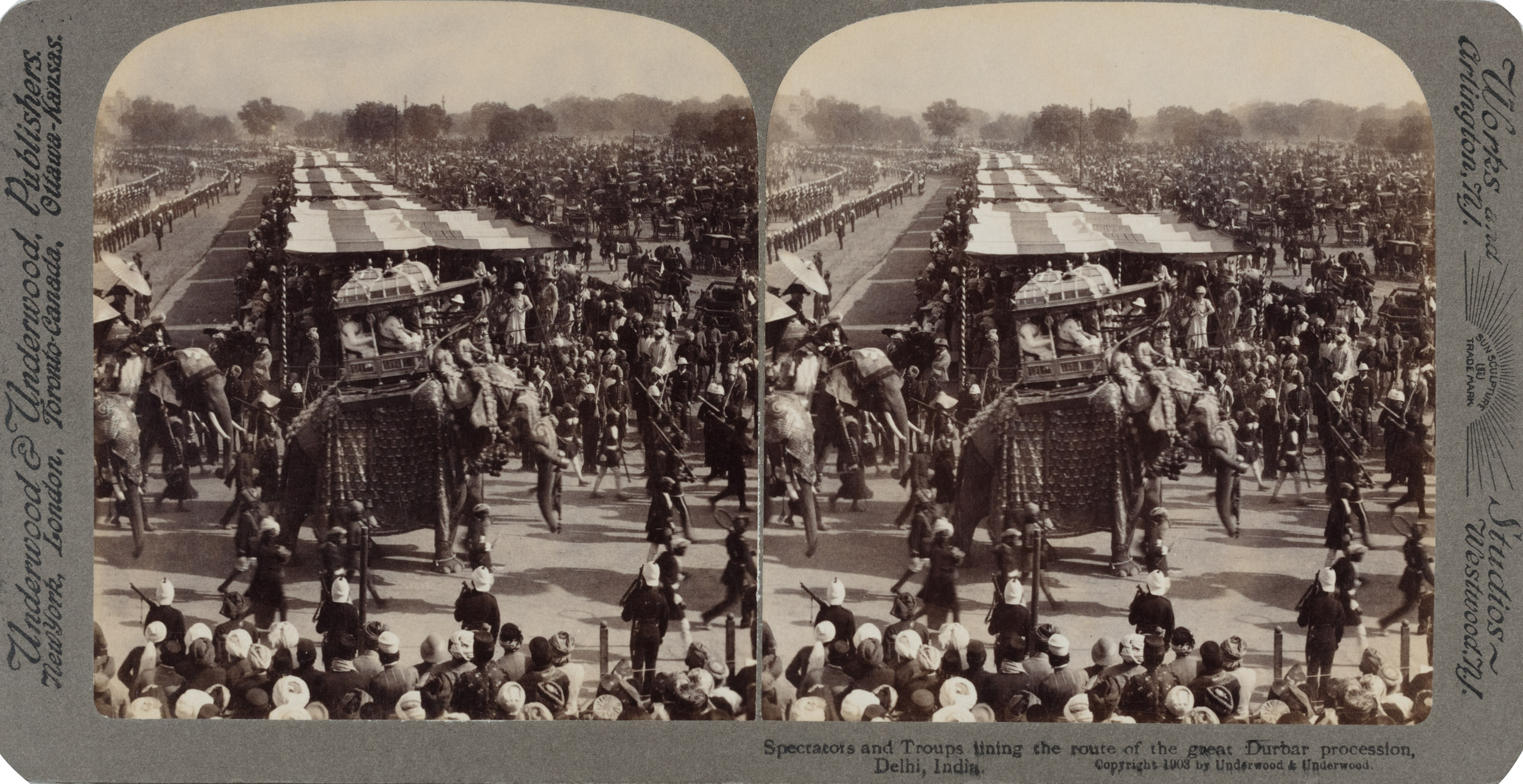

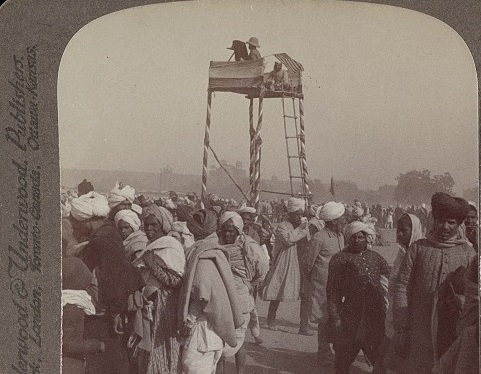

Underwood and Underwood (publisher)

Detail from The Delhi Durbar Through the Stereoscope

Silver albumen prints mounted on stereoscopic card, letterpress caption, 8.6 x 17.7 cm., 1903

Collection: DAG

|

An instrument for enhancing the illusion of depth in paired photographic images, stereoscopes were being presented as early as 1838 by Charles Wheatstone, serving as a visual aid to a scientific paper. Soon, however, developments in photography took Wheatstone's innovation in new directions. |

|

|

A stereoscope is an instrument, somewhat like a binocular, in which two photographs of the same scene or object, taken from slightly different angles, are simultaneously presented, one to each eye. It works by presenting each eye with a lens that makes the image seen through it appear larger and more distant (giving the image a deep surface) and it also appears to shift in its horizontal position, so that for a person with normal binocular depth perception, the edges of the two images seemingly fuse into one ‘stereo window’. Stereoscopic viewing is achieved by the brain ‘computing’ the spatial information from the difference between the two pictures on the retina and creating a joint overall image, which provides extra information about the distance to an object. This process is called stereoscopic vision. |

|

|

James Ricalton photographing the Delhi Durbar

Image courtesy: Wikimedia Commons

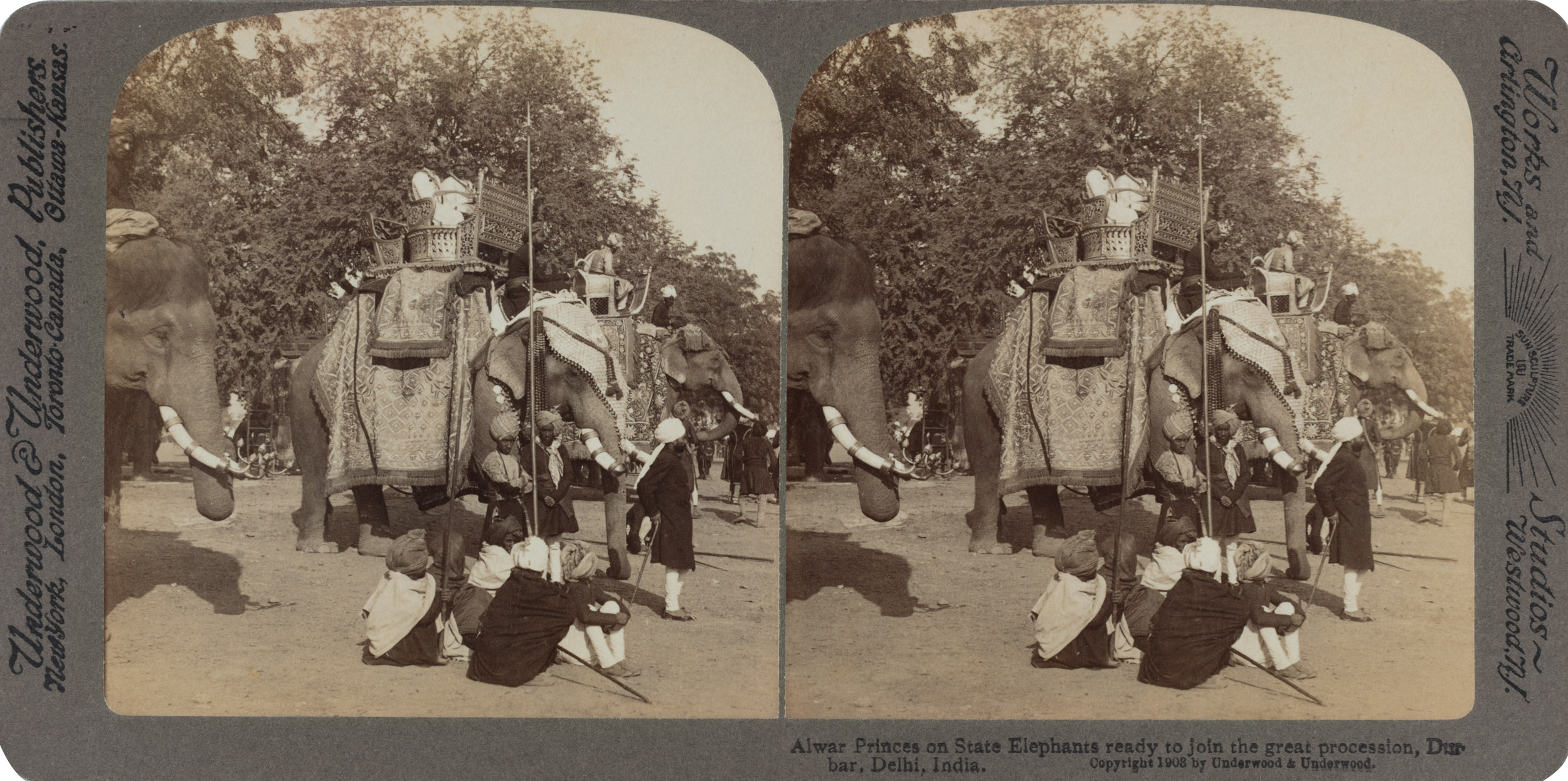

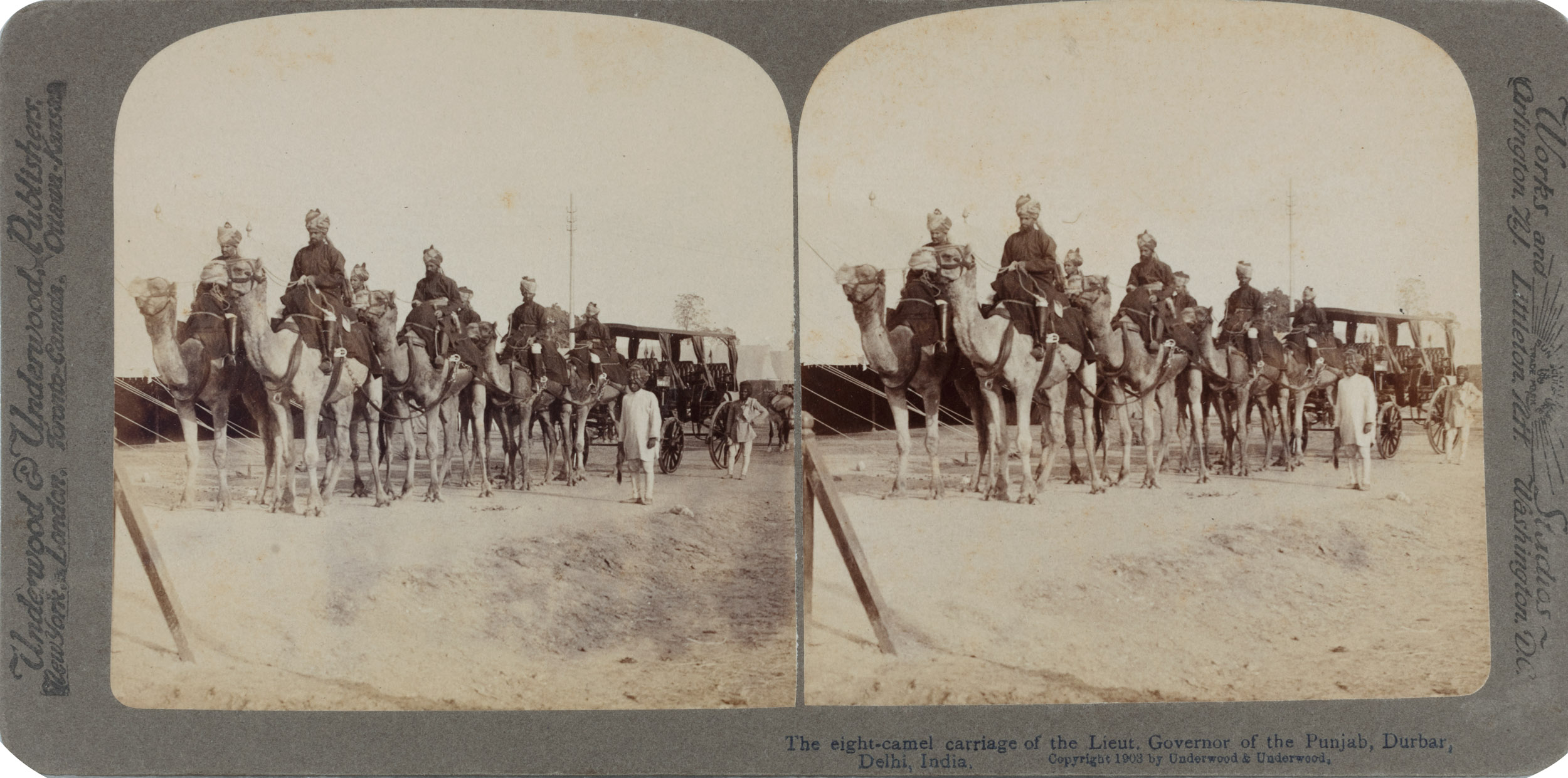

Underwood and Underwood was a company that specialized in stereoscopic photography and was founded in 1881 by two brothers, Elmer and Bert Underwood. The company was one of the largest publishers of stereographs in the world and produced millions of stereoscopic images. James Ricalton (1844—1929) was an American photographer and lecturer who traveled extensively, documenting his journeys with stereoscopic photography. He worked with Underwood and Underwood to publish his images and helped to popularize the use of stereoscopes by creating stereographic images of different cultures and countries, such as India and China. One of the most popular albums they worked on covered one of the Delhi Durbars, titled The Delhi Durbar Through Stereoscope, published in 1903. |

|

Just as two nearly identical images met to create an illusion of harmony and depth, Ricalton hoped two cultures would be reconciled through the images he produced. ‘We shall learn how much England has done to improve the condition of this oriental world of many races, tribes, languages and religions. We shall be the western descendants meeting the eastern descendants of a common, but remote ancestry—the Aryans.’ -James Ricalton, India Through the Stereoscope |

|

|

What were the advantages of seeing India through the stereoscope? Ricalton enumerated several ones in his writings, emphasizing especially the comfort and aesthetic experience offered by the images abstracted from the reality of the place. An early intimation of the armchair tourist, in other words, for whom the ethnographic knowledge produced by the images, paired with heir picturesque aesthetic, made it more valuable than an experiential awareness of the place itself. ‘Few are able, personally, to visit that teeming world empire (in India): but it is now becoming well-known, that, next to real travel and personal observation, the stereographic itinerary affords a most realistic, permanent, and pleasurable alternative. It is not exaggeration to state that I am frequently meeting those who have acquired a fuller and more accurate knowledge of places and things in foreign countries by means of stereographs accompanied by special maps and guide books, than I myself possess after visiting the places and seeing those things on repeated occasions.’ (Ricalton, India Through the Stereoscope) |

|

‘Many wonderful things in India, when seen in reality, are often in a debilitating temperature, and under liabilities to pestilential maladies, while, when seen through the stereoscope, the expense is a trifle; there is no exposure to pestilence; you are among the comforts of home; it is wonderland you reach directly from the fireside. Besides, there is often a witchery and a charm in stereoscopic scenes not found in the real presence of places and things.’ - James Ricalton, India Through the Stereoscope |

|

|

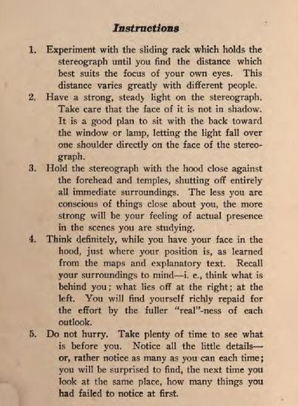

Ricalton’s book was also filled with several kinds of instructional passages. On how to use the stereoscope, how to position oneself, and what the best positions are in India for making stereographic images. He detailed one hundred places where such images could be made, stretching across the Empire from one’s first landing in Bombay to the west, towards Darjeeling and many other places besides. This resulted in the creation of a product like the stereoscope, that also came fitted with readymade itineraries, views and viewing practices. The viewing practice itself sought to be immersive, aiming to become as natural a surrogate for the real place as possible. Ricalton always emphasized the supplementary nature of the stereoscope, that must be used alongside maps and texts; one of his instructions suggests, ‘Think definitely, while you have your face in the hood, just where your position is, as learned from the maps and explanatory text. Recall your surroundings to mind — i. e., think what is behind you; what lies off at the right; at the left. You will find yourself richly repaid for the effort by the fuller "real"-ness of each outlook.’ |