|

Argot Term of the Month: The Artists’ VillageAnkan Kazi June 01, 2024 Artists' villages and communities have a rich history around the world, serving as hubs for artistic collaboration, experimentation, and cultural exchange. In India, several notable artists' villages have emerged, each with its own unique story and contribution to the country's artistic landscape. The history of artists’ communes provokes us to ask broad questions about the genealogy of art education in India, the locations that have contributed to it and the role exchanges between artists have played in the development of modern art in India. |

K. C. S. Paniker

The Foot Bridge (detail)

Watercolour on paper pasted on paper, 1950, 15.5 x 16.7 in.

Collection: DAG

|

Artists’ villages have a long and storied influence on the development of modern art movements, schools and practices all over the world. However, keeping our lens on Indian artists’ communities, some strains may be detected in western artists’ villages that fed into common agendas that were taken up by Indian artists too. Proximity to nature was a crucial point for undertaking this exercise. Even during the high noon of academic studio practices in Europe, artists continued to seek the outdoors for inspiration—as exhorted by Romantic poets and philosophers of the time. |

|

|

Théodore Rousseau

Becquigny, Somme

c. 1857

Image Courtesy: Wikimedia Commons

Jean-François Millet

The Sower

1865

Image Courtesy: Wikimedia Commons

In the mid-nineteenth century, Barbizon, a quaint village nestled in the Fontainebleau Forest near Paris became a haven for artists seeking inspiration from the surrounding natural beauty and a departure from the bustling urban landscapes of Paris. The Barbizon School emerged as a reaction against the academic conventions of the time, which favored historical or mythological subjects over scenes from everyday life. Instead, artists like Jean-François Millet, Théodore Rousseau, and Charles-François Daubigny found solace in the simplicity of rural life, depicting peasant farmers, pastoral scenes, and the tranquil beauty of nature. Artists would often work en plein air, setting up their easels outdoors to observe firsthand the interplay of light and shadow across the landscape. This dedication to direct observation and a keen appreciation for the nuances of nature laid the groundwork for the Impressionist movement that would follow. |

Nandalal Bose

Collection: DAG

This would be an important consideration for the various Indian artists’ communes too. And it makes us ask if places like the Kala Bhavana, Santiniketan’s art school, lodged equally within an institutional complex and the bucolic Bengali countryside, could be considered along the same lines too. While the question of Santiniketan is more complicated—perhaps only originating as a communal space—we can turn to look at some of the purposes for setting up artists’ villages in India. |

|

Villages like Raghurajpur in Odisha have been instrumental in preserving ancient art forms like Pattachitra paintings, palm leaf engraving, folk painting, and mask making. On the other hand, artists' villages like Pochampally in Telangana have showcased regional art forms like Ikkat weaving, providing visitors with a glimpse of the intricate processes and designs unique to the region. Villages such as Cholamandal in Chennai have been hubs for artistic experimentation and collaboration—and, in its original vision, also meant to promote and preserve regional arts and craft traditions. Cholamandal, India's largest self-supporting artist village, has been a space where artists can immerse themselves in art, learn about the history of various art forms, and engage in sculpting and other artistic endeavors. Artists' villages attract not only local artists but also visitors and tourists interested in learning about different art forms. Tourists often stay for extended periods to immerse themselves in the artistic way of life of these villages, gaining insights into the cultural and artistic traditions of the region. |

|

|

|

Which were some of the more significant artists’ communes or villages in India? |

|

|

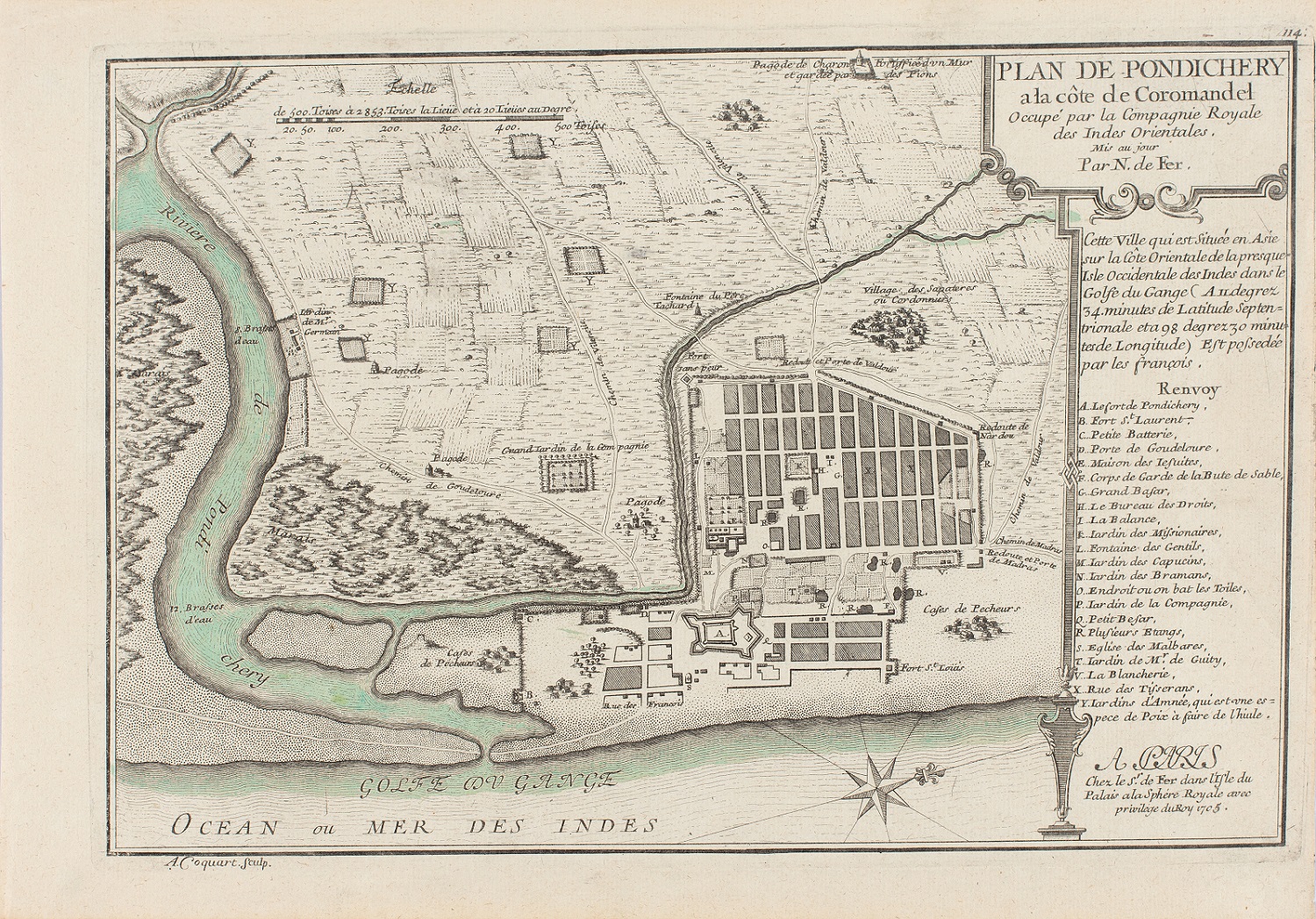

K. C. S. Paniker

The Foot Bridge

Watercolour on paper pasted on paper, 1950, 15.5 x 16.7 in.

Collection: DAG

S. G. Vasudev

Vriksha

Oil on canvas board, 1984, 16.2 x 12.2 in.

Collection: DAG

One of the most significant examples is the Cholamandal Artists' Village, established in 1966 near Chennai, Tamil Nadu. Founded by artist and pedagogue K. C. S. Paniker, Cholamandal was envisioned as a ‘refuge in which artists could live and work communally while sustaining themselves through their artistic practice.’ The village was named after the Chola dynasty, known for their patronage of the arts, and it emerged from the Madras Art Movement of the 1960s, which sought to establish a regional artistic sensibility specific to South India. Cholamandal was founded with proceeds from craftwork exhibitions conducted by the Artists’ Handicrafts Association. Lodged on the scenic Coromandel coast, which had a long entanglement with colonialism and was persistently mapped over the colonial period, it provided a communal living and working space for artists who wanted to break away from traditional forms and explore modern and contemporary art—and also commit towards making a career out of art. It was beneficial for women artists especially, because it allowed them to purchase plots of land and build studios for their continued work, a source of material support that was not always available. |

P. Gopinath

Untitled

Acrylic and ink on paper, 1998, 10.0 x 9.0 in.

Collection: DAG

Cholamandal Arts Village

Image courtesy: Wikimedia Commons

Collection: DAG

The village became a hub for experimentation and innovation, fostering a vibrant artistic community. As a scholar has written, ‘The Cholamandal Artists’ Village reinforced (Paniker’s) ideology of the Indian in spirit by a conscious link with past heritage, as well as a mark of continuity with tradition.’ The impact of Cholamandal Artists' Village on Indian art has been profound. It provided a supportive environment for artists to collaborate, exchange ideas, and experiment with new techniques and styles. Many renowned Indian artists emerged from this community, contributing significantly to the development of modern and contemporary art in India, ranging from early masters like V. Viswanadhan, S. G. Vasudev and M. Reddeppa Naidu to S. Nandagopal, J. Sultan Ali and P. Gopinath. Paniker’s method of allocating land (he owned a small parcel of it, most of the rest being owned by the Artists’ Association) and advocating partial ownership for artists until they committed to a communal and cooperative agenda occasionally tipped over into tussles over land and property, allowing him to dictate who could and could not live there for extended periods of time. Overall, however, it proved successful, and is still surviving, with its Art Gallery that regularly displays work. |

|

Additionally, the village played a crucial role in promoting Indian art internationally, showcasing the diversity and creativity of Indian artists on the global stage. Besides painting and sculpting, like in Kasauli (see below), Cholamandal also became a space that encouraged interdisciplinarity and the exploration of related artforms like dance, drama, music and poetry. According to the dancer Aditi De: ‘An outdoor theatre-in-the-round saw the colony widen its horizons to embrace other arts under the ozone-tossed stellar skies. The performing space named Bharathi, after the Tamil poet, has hosted a galaxy of visitors—Balasaraswathi and Yamini Krishnamurthy doing Bharathanatyam. A. K. Ramanujam reading his poetry and Girish Karnad his plays.’ |

|

|

S. G. Vasudev

Humanscape

Oil on canvas, 1992, 48.0 x 48.0 in.

Collection: DAG

S. Nandagopal

Bird

Silver plated copper and brass supported by iron armature, 29.7 x 23.5 x 9.5 in.

Collection: DAG

At Cholamandal, Paniker also found space to articulate something even more radical than simply a site for an artists’ commune, saying that he envisioned the village to be an alternative to the colonial-era art schools. As a Principal of the art school at Chennai, this was another turn of the screw in Paniker’s project of reforming the art education agenda for a new, postcolonial nation like India that was a composite of diverse cultures from various regions that could be given a chance to express their autonomous developments. He is quoted as saying, ‘Art institutions in general have failed to fit the artist to life. Cholamandal will begin taking in fresh art students from the year 1971. The student will choose his own master and will work under his supervision for a period of two years… During this period he will apply himself to two congenial crafts in addition to his main subject of study, namely painting or sculpture.’ Although his vision failed to materialise in this regard, it is worth pointing out that in these plans to create an alternative to the colonial model of art education there was always the danger of submitting it to the normative educational principles of centrally-dictated board of grants like the University Grants Commission, which currently oversees the educational syllabi of Santiniketan’s Visva Bharati University. |

|

Another important artists' village is the Kasauli Art Centre, located in the northern Indian state of Himachal Pradesh. Kasauli has a long history as a hub for artists, writers, and intellectuals, attracting figures such as Rudyard Kipling and Rabindranath Tagore in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. The town's picturesque setting and cool climate made it a popular retreat for creative minds seeking inspiration and respite from the heat of the plains. |

|

|

K. G. Subramanyan

Untitled

Ink and watercolour on paper, 1954, 13.2 x 11.0 in.

Collection: DAG

Amrita Sher-Gil

Untitled

Watercolour and graphite on paper, 3.7 x 5.0 in.

Collection: DAG

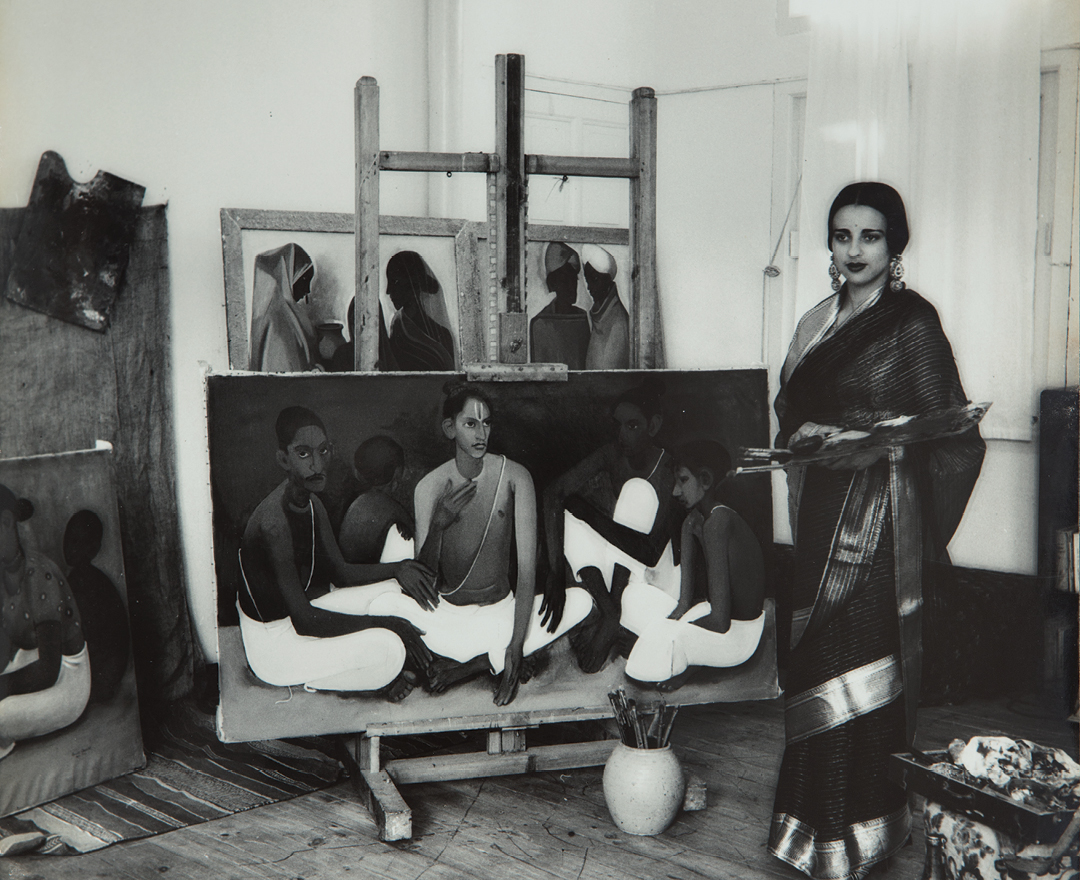

Amrita Sher-Gil at work

The Kasauli Art Centre, established by artist and writer Vivan Sundaram in 1976 at his ancestral property, Ivy Lodge, in Kasauli, Himachal Pradesh, played a pivotal role in the world of Indian art from 1976 to 1991. Belinder Dhanoa's Kasauli Art Centre 1976-1991 outlines the significance of this art center during its 15 years of operation. Besides Sundaram, artists and writers formally associated with Kasauli included B. N. Goswamy, Geeta Kapur, Romi Khosla, Gulammohammed Sheikh and K. G. Subramanyan. Due to the presence of influential art critics and historians like Kapur and Goswamy, the Art Centre was inevitably inclined towards critical interventions into the minoritarian agendas of modern art, especially with respect to gender and nationalism. Ivy Lodge, a historic building in Kasauli and erstwhile residence of the artist Amrita Sher-Gil, served as the venue for the Kasauli Art Centre, providing a space for artists to gather, collaborate, and engage in various art-related activities. The center hosted numerous exhibitions, workshops, and discussions, attracting artists, writers, and intellectuals from across India and abroad. Locating it in a house associated with an iconic modern artist like Sher-Gil (who was Sundaram’s aunt) points to another agenda for such artists’ villages—to put personally significant locations and retreats on the map of Indian art history, in an attempt to construct a secular geography of exchange and commitments that were not bound by institutional goals and agendas. |

K. G. Subramanyan

Untitled

Gouache on handmade paper, 2008, 18.2 x 15.2 in.

Collection: DAG

Vivan Sundaram

Passage

Oil on canvas, 1981, 36.2 x 69.2 in.

Collection: DAG

Kasauli Hills

Image courtesy: Wikimedia Commons

The center served as a hub for contemporary art practices, providing a platform for artists to experiment with new mediums and ideas. Shows were held, like an exhibition titled Seven Young Sculptors in 1985, curated by Sundaram and featuring works by Pushpamala N., Alex Matthew and others. Theatre workshops were also conducted and plays were staged, like the Hindi adaptation of Rabindranath Tagore’s novel Ghare Baire (The Home and the World), by Anuradha Kapur and Rustom Bharucha. Incidentally, the play was translated into Hindi (Ghar aur Bahaar) by the novelist Geetanjali Shree. The Kasauli Art Centre also played a significant role in preserving and promoting traditional art forms. It organized workshops and demonstrations to showcase the skills of local artisans and ensure the continuity of these practices. In October 2023, an exhibition of documents and works produced at the Art Centre was held at the Museum of Fine Arts, Panjab University, Chandigarh, that was produced by the team at Sher-Gil Sundaram Arts Foundation in collaboration with the Department of Art History & Visual Arts, Panjab University. Through its various initiatives and events, the Kasauli Art Centre contributed to the development of Indian art by providing a space for artists to connect, learn, and grow. The center's impact on the art scene in India during its 15 years of operation is a testament to the importance of such spaces in nurturing artistic talent and fostering cultural exchange. |

|

Andretta is a unique artists' village located in the Kangra Valley of Himachal Pradesh, India. It was established in the 1920s by Norah Richards, an Irish writer and dramatist who settled in Andretta, where she began promoting and encouraging various art forms. She invited artists like the painter and sculptor B.C. Sanyal, and over time it became a hub of cultural and theatrical activities. |

|

|

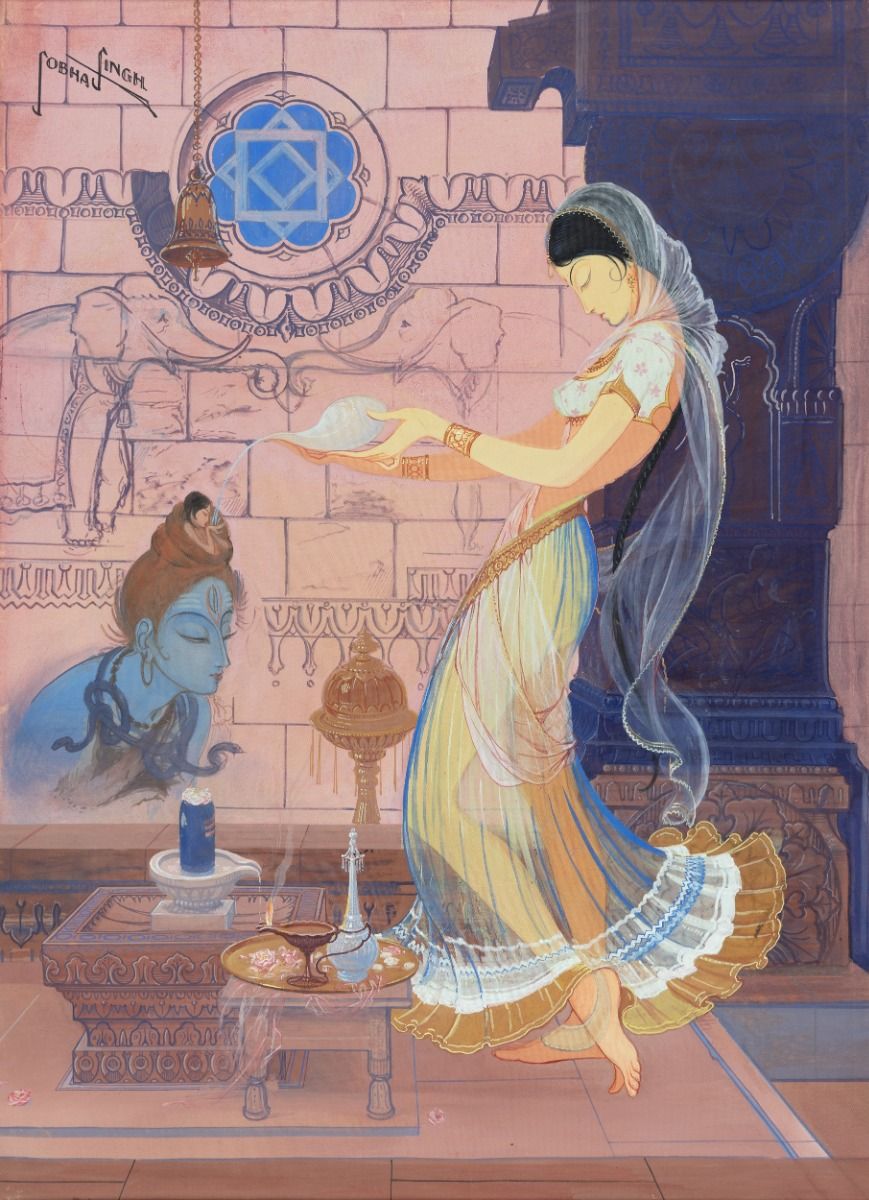

Sobha Singh

Shiva's Devotee

Gouache on fabric pasted on mount board,

Collection: DAG

Gogi Saroj Pal

Young Monks

Oil on canvas, 1982, 24.0 x 24.0 in.

Collection: DAG

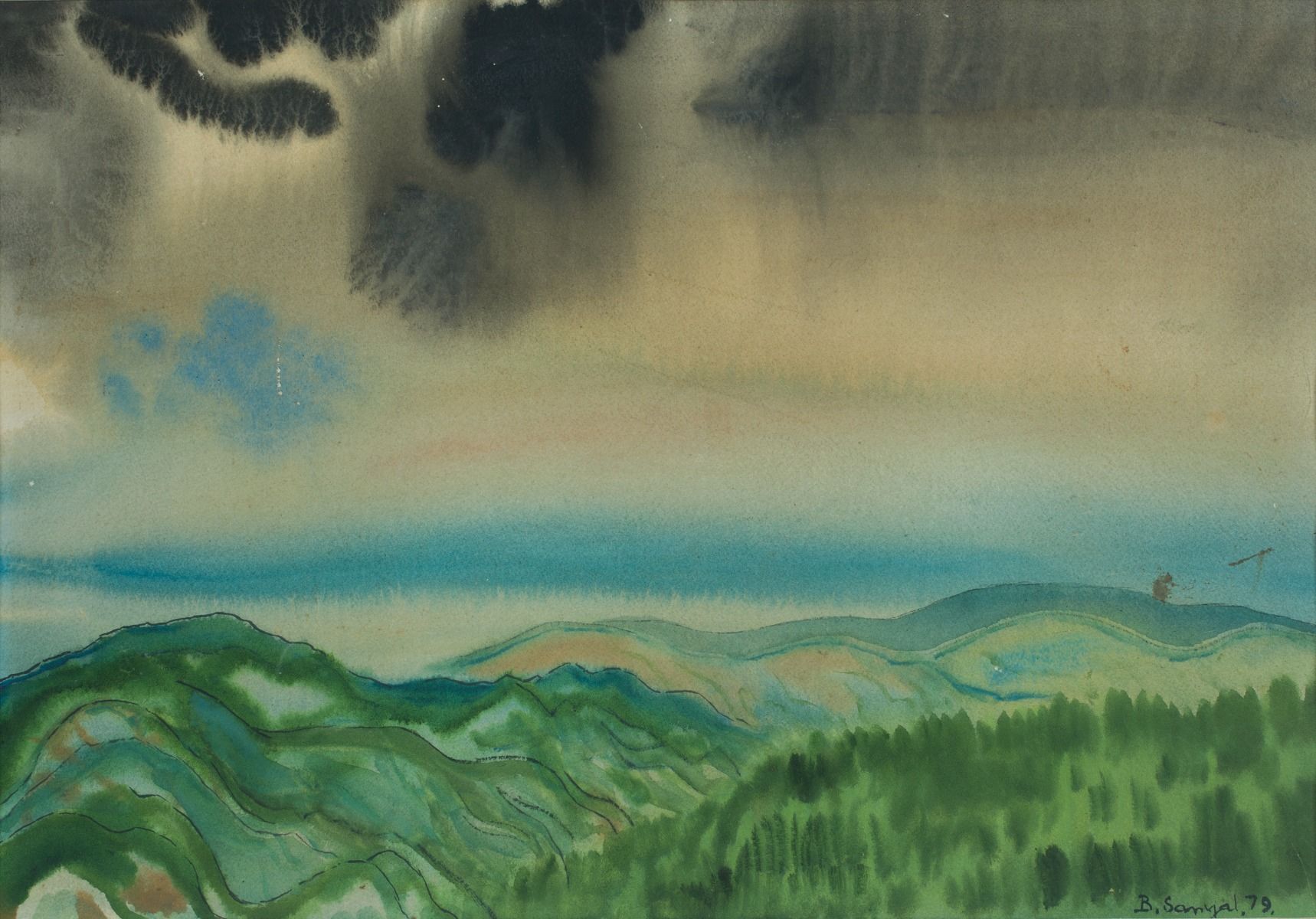

B. C. Sanyal

Untitled

Watercolour wash and charcoal on handmade paper, 1979, 15.2 x 19.0 in.

Collection: DAG

Richards built a mud house called ‘Chameli Niwas’ and started teaching drama to students from Punjab and other parts of the country. She organized an annual week-long festival where students and villagers would enact her plays focused on social reform. Renowned artists like Prithviraj Kapoor and Balraj Sahni were regular guests at these festivals. The village complex includes several centers worth exploring, such as Norah's Centre of Arts, Andretta Pottery & Craft Society, Norah's Mud House, and Sir Sobha Singh Art Gallery. Other famous artists who made Andretta their home include painter and sculptor Sobha Singh, known for his mythological works, and artist Sardar Gurcharan Singh, whose son Mini runs the Andretta Pottery and Craft Society today. Later, artists like Gogi Saroj Pal would also visit and learn from Andretta. The village continues to attract artists, dancers, writers, and other creative individuals from around the world and has since become a tourist attraction for its scenic beauty as well. |