|

Argot Term of the Month: Figure DrawingShreeja Sen August 01, 2023 The advent of abstraction is a defining moment in art history as we devise divisions between representational, figurative, and abstract art, with the need arising from this pivotal formal shift in the modern world. The term ‘figurative’ has come to represent an antithesis of sorts to the term abstract. One is representational of reality, the latter a derived (abstracted) representation or even non-representational (colour-field paintings for example). ‘Figurative art’, therefore is any artwork that retains distinct references to the forms of the real world—the human figure but also animal or inanimate figures. |

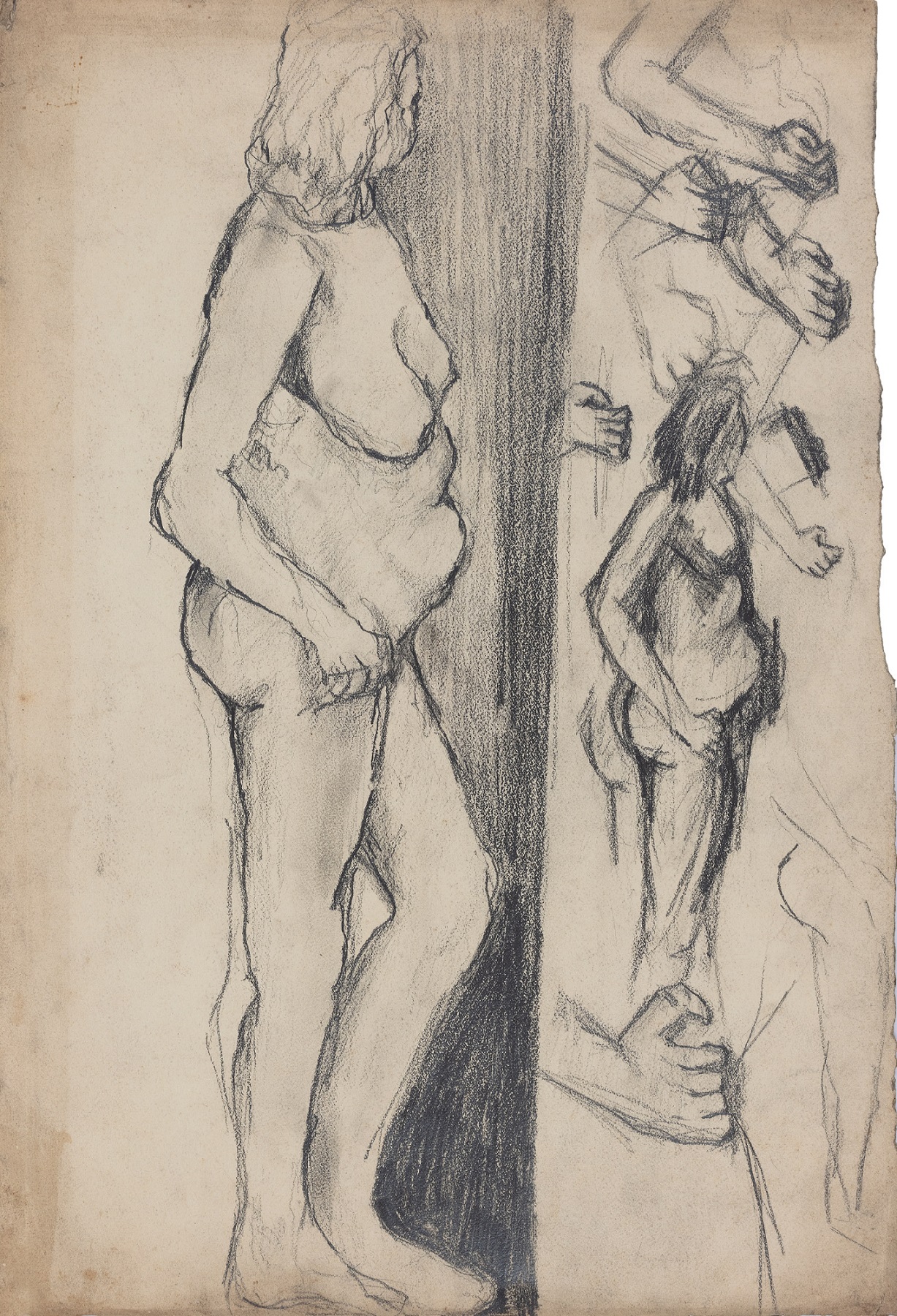

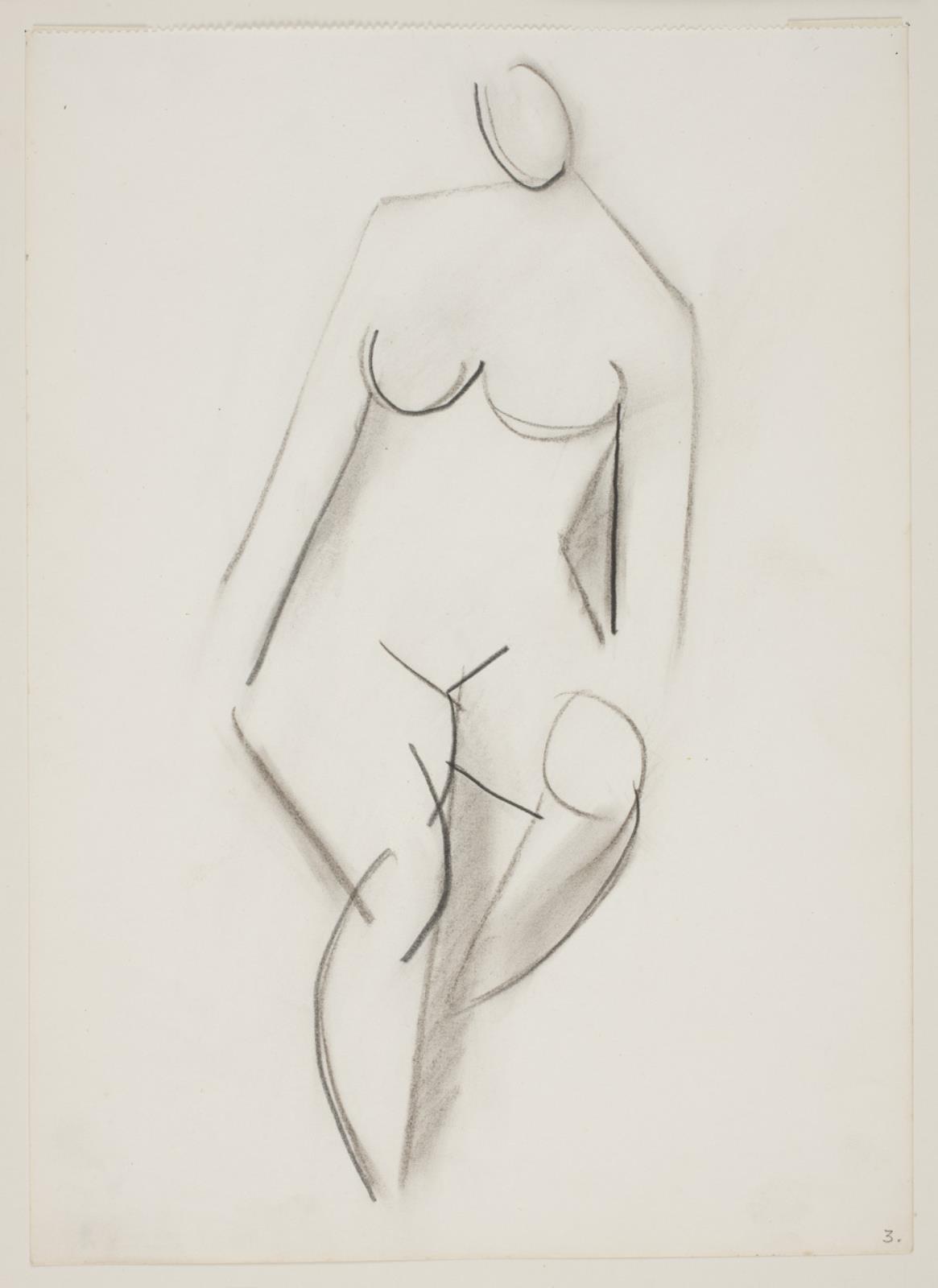

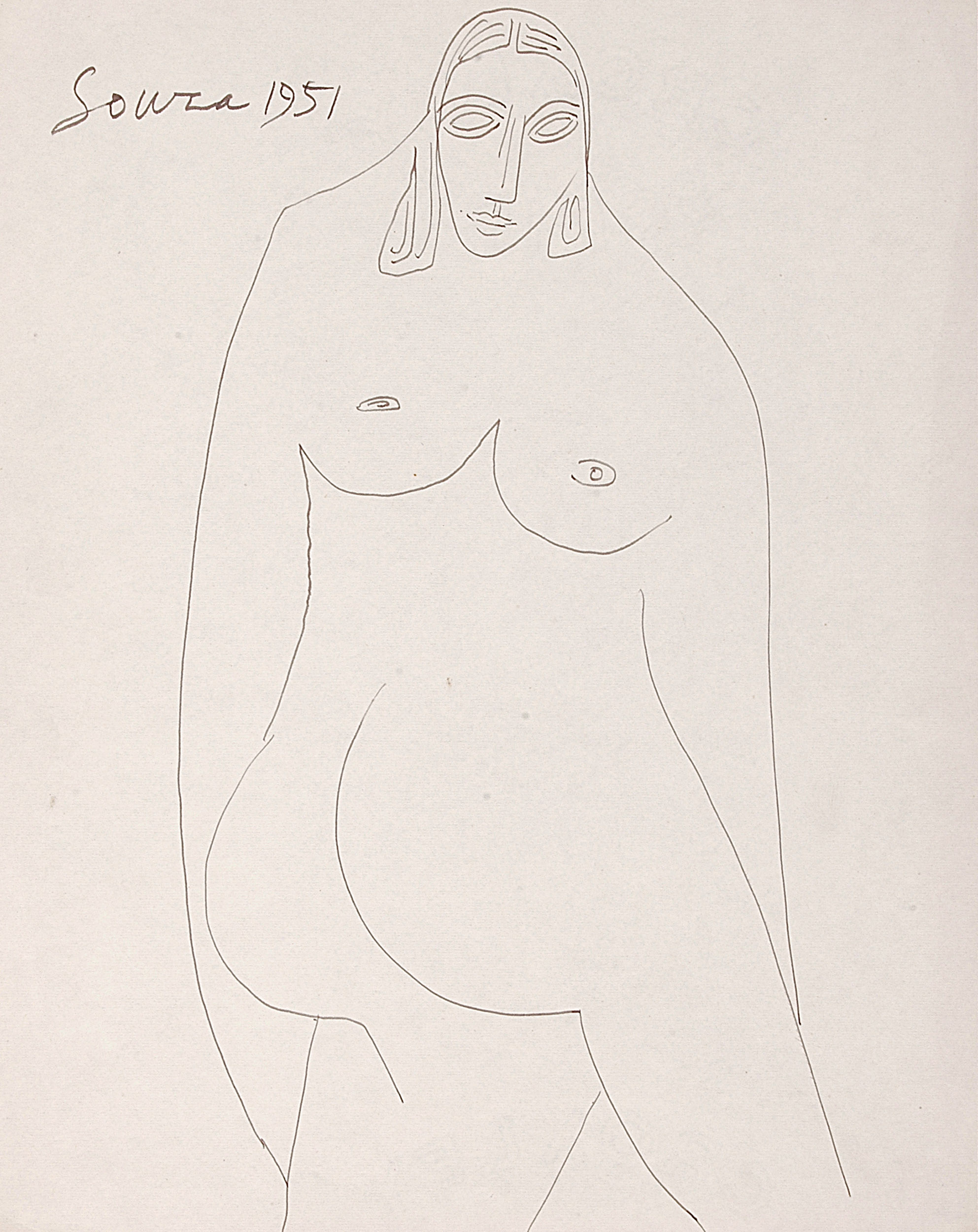

F. N. Souza

Untitled

Collection: DAG

|

‘Figure drawing’, on the other hand, is a term and a practice whose roots are much more ancient, and linguistic usage much more literal and anthropocentric. Figure drawing refers to the human body depicted via any drawing media such as Conté crayons (sticks of wax, oil, and pigment), charcoal, pencils, ink etc. How did this history—taking shape in the western tradition, which was taught through colonial art schools—impact the world of Indian art? We try to highlight some of the important aspects of this term in our recurring series, Argot, where we seek to demystify some of the major ideas from the world of art. |

|

|

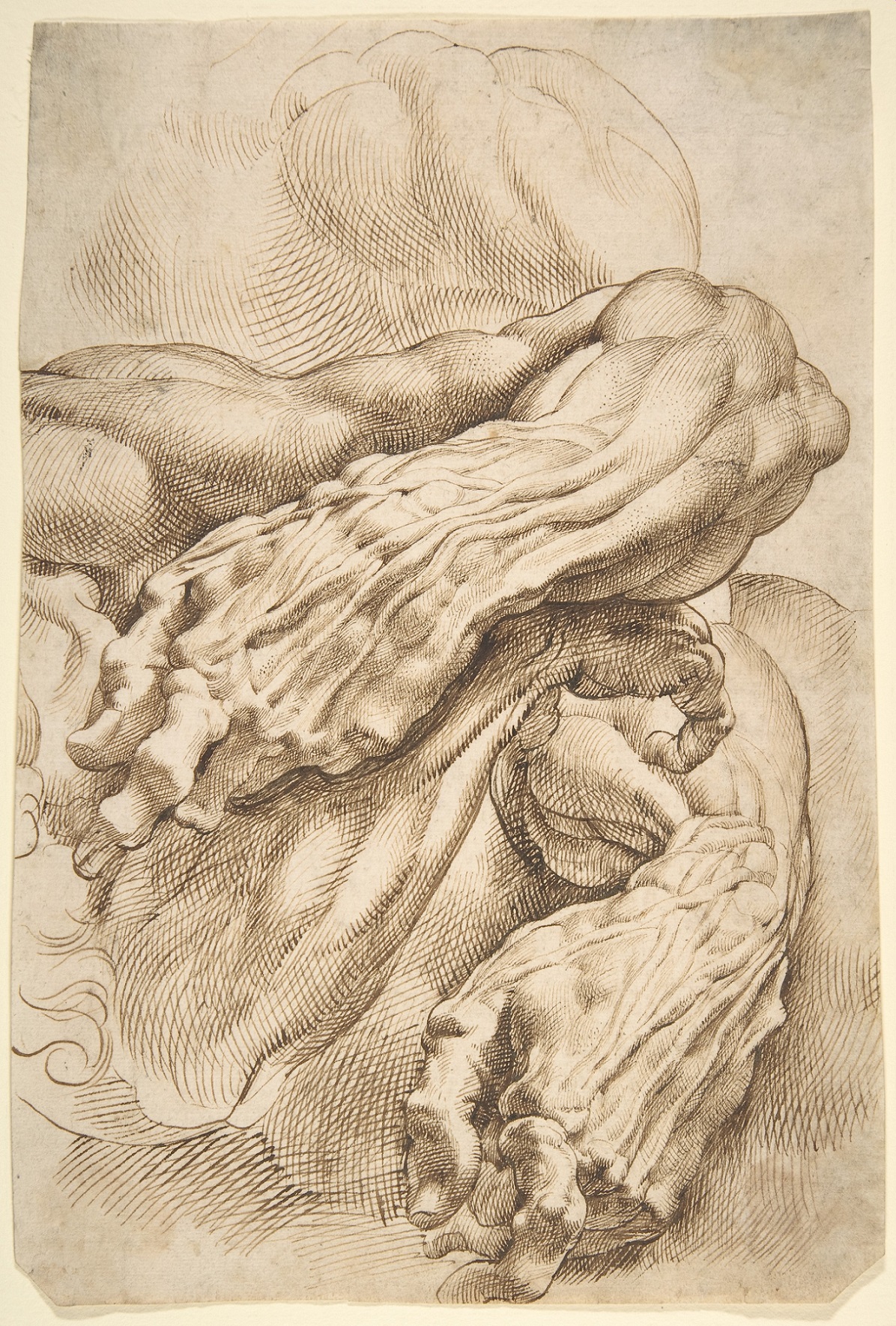

Peter Paul Rubens

Anatomical Studies: a left forearm in two positions and a right forearm

Pen and brown ink, (27.8 x 18.6 cm., ca. 1600–1605

Image courtesy: The Metropolitan Museum of Art (Public Domain)

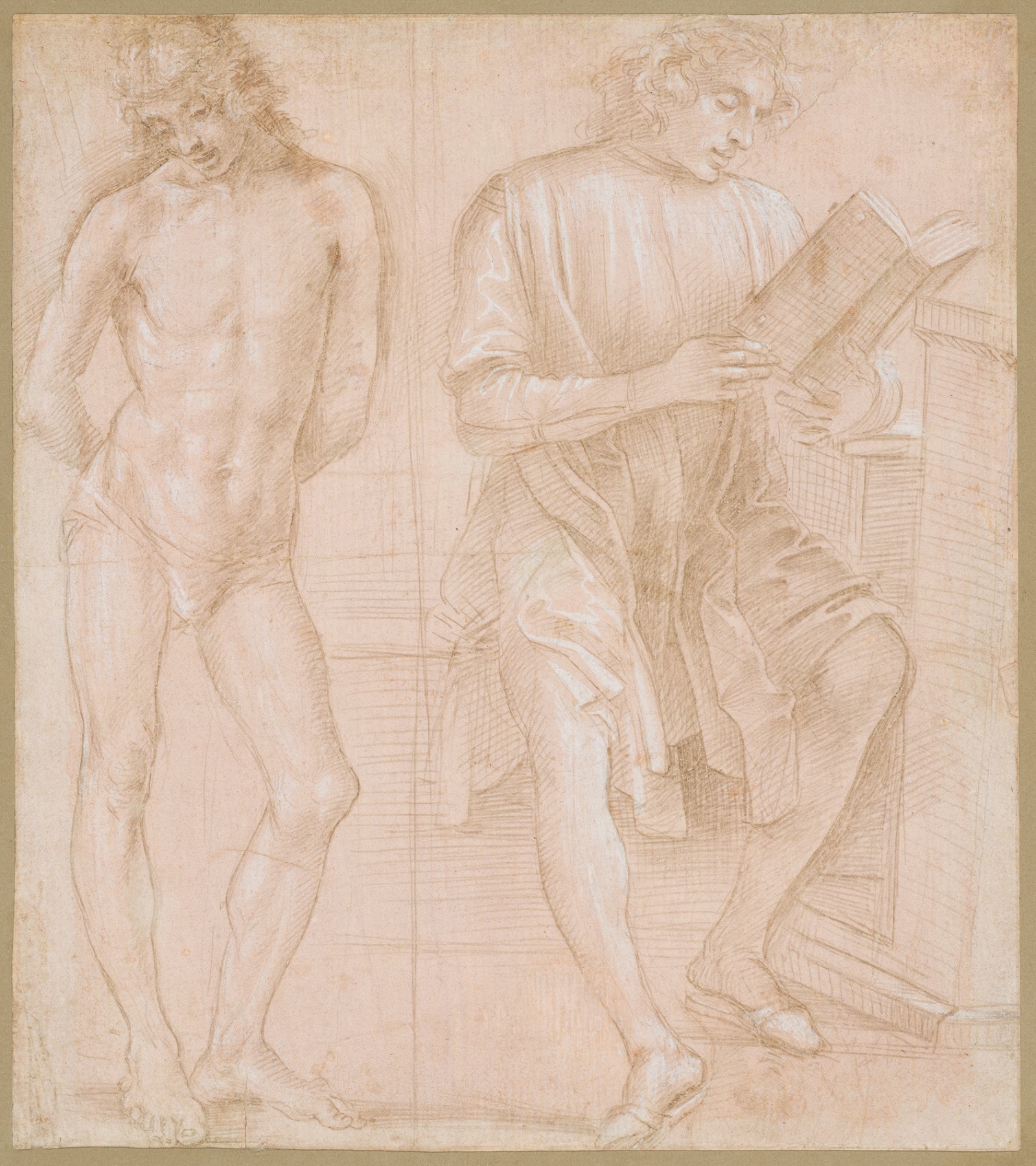

Filippino Lippi

Standing Youth with Hands Behind His Back, and a Seated Youth Reading

Metalpoint, highlighted with white gouache, on pink prepared paper, 24.5 x 21.6 cm.

Image courtesy: The Metropolitan Museum of Art (Public Domain)

Michelangelo Buonarroti

Studies for the Libyan Sibyl and a small Sketch for a Seated Figure

Red chalk, with small accents of white chalk on the left shoulder of the figure in the main study, (28.9 × 21.4 cm.

Image courtesy: The Metropolitan Museum of Art (Public Domain)

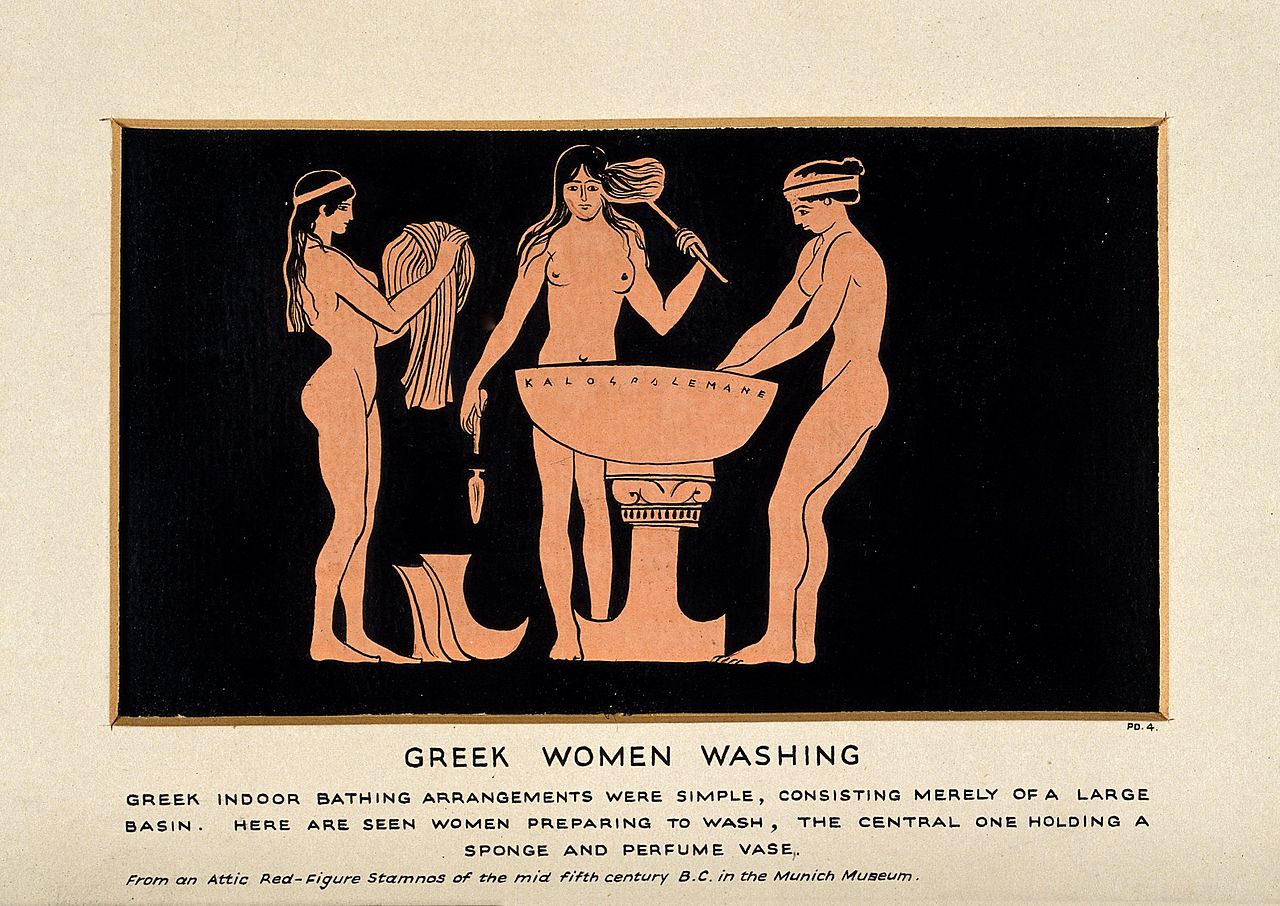

Kenneth Clark goes as far as to suggest that it was the Greeks in the fifth century B. C. who invented the art form of the nude, as a contribution to the concept of ‘ideal beauty’. He refers to popular Greek painter Zeuxis’ documented practice of drawing a composite of features from several maidens of Kroton to arrive at his notion of ideal form. |

|

This faithfulness to the notion of ideal beauty has been interpreted as a celebration of naturalism and finds its way into the Renaissance where artists were often some of the best anatomists. In an era that privileged life-like sculptural portrayal of the human figure, drawings and especially life drawings became a crucial element. Also called cartoons, preparatory sketches for sculptures would define the level of detail and countouring in figural sculptures. Leonardo Da Vinci and Michaelangelo were both artist-anatomists having dissected human bodies to augment their understanding of the human body, and, unlike artists of antiquity, focused on the male form as the ideal. |

|

|

|

The significance of figure drawing, especially model drawing, becomes apparent as it becomes a fundamental and foundational aspect of artistic training. Interestingly, although held as a formative essential for artists, female students were denied access to live models and had to practice figure drawings based on casts, until the late 19th century. Linda Lochlin’s 1971 essay, ‘Why Have There Been No Great Women Artists’, cites this lack in female education as the reason for most women being restricted to portraitures, still lifes and landscapes in an era where the general consensus privileged history paintings as the highest form of art. |

|

|

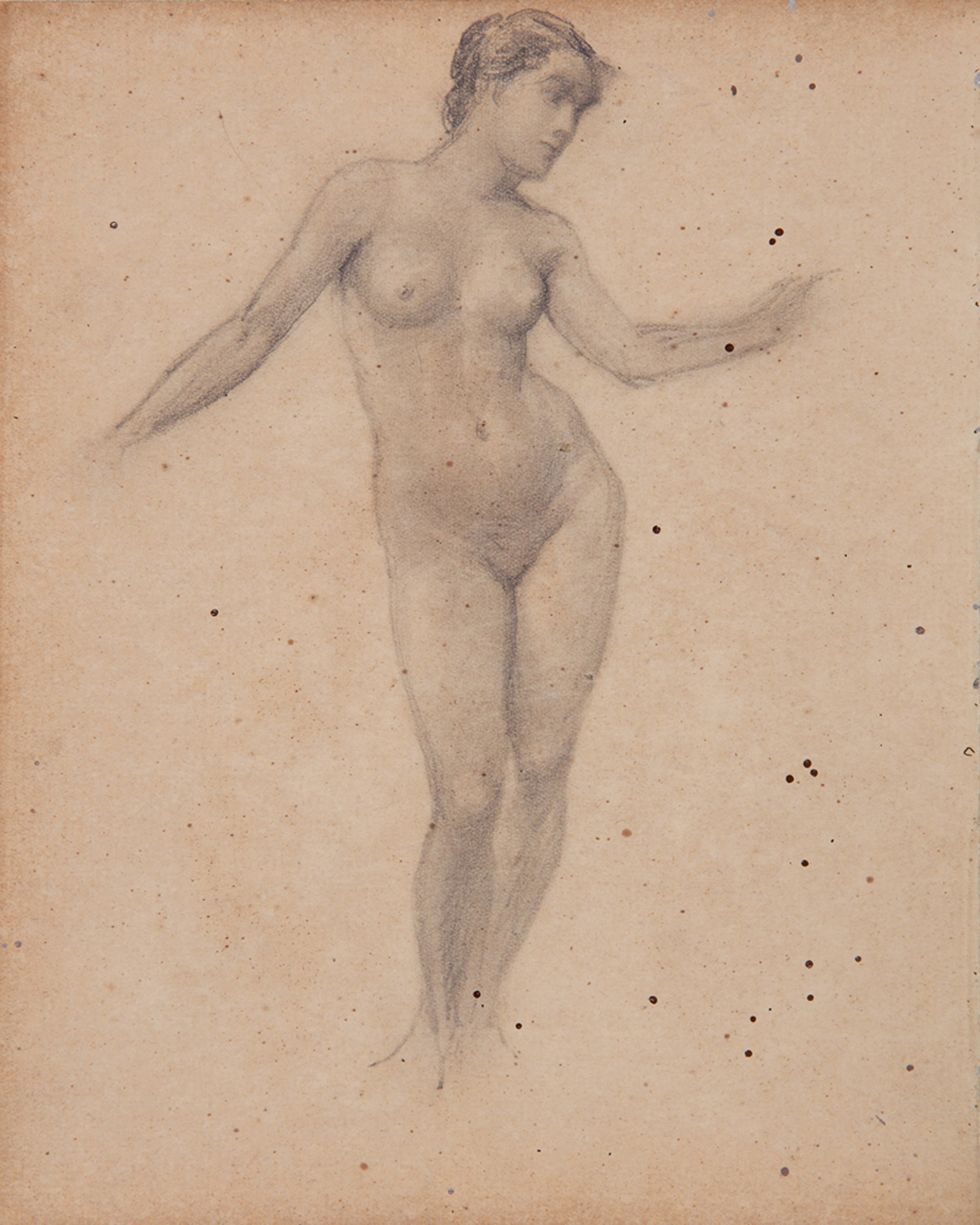

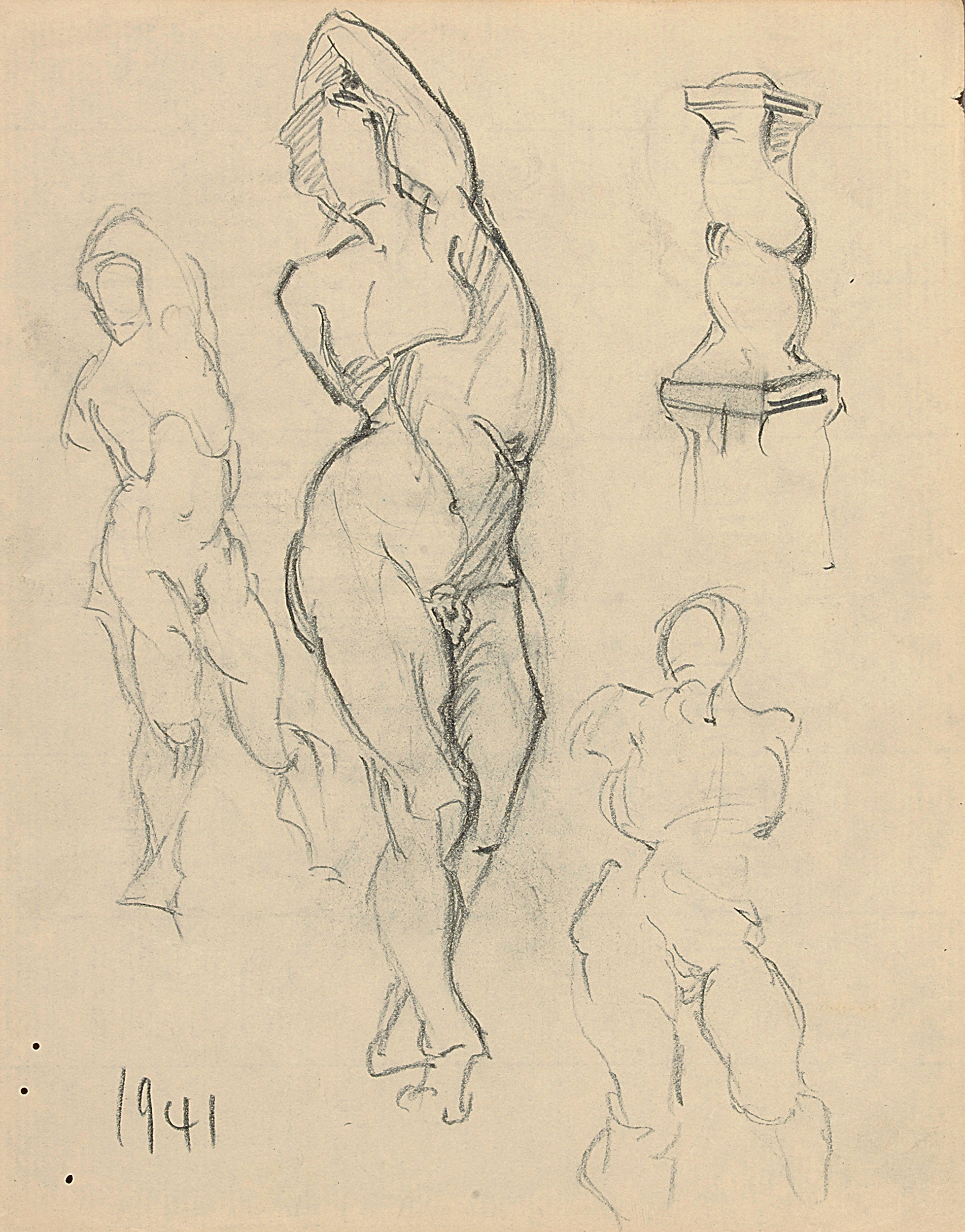

M. V. Dhurandhar

Untitled

Collection: DAG

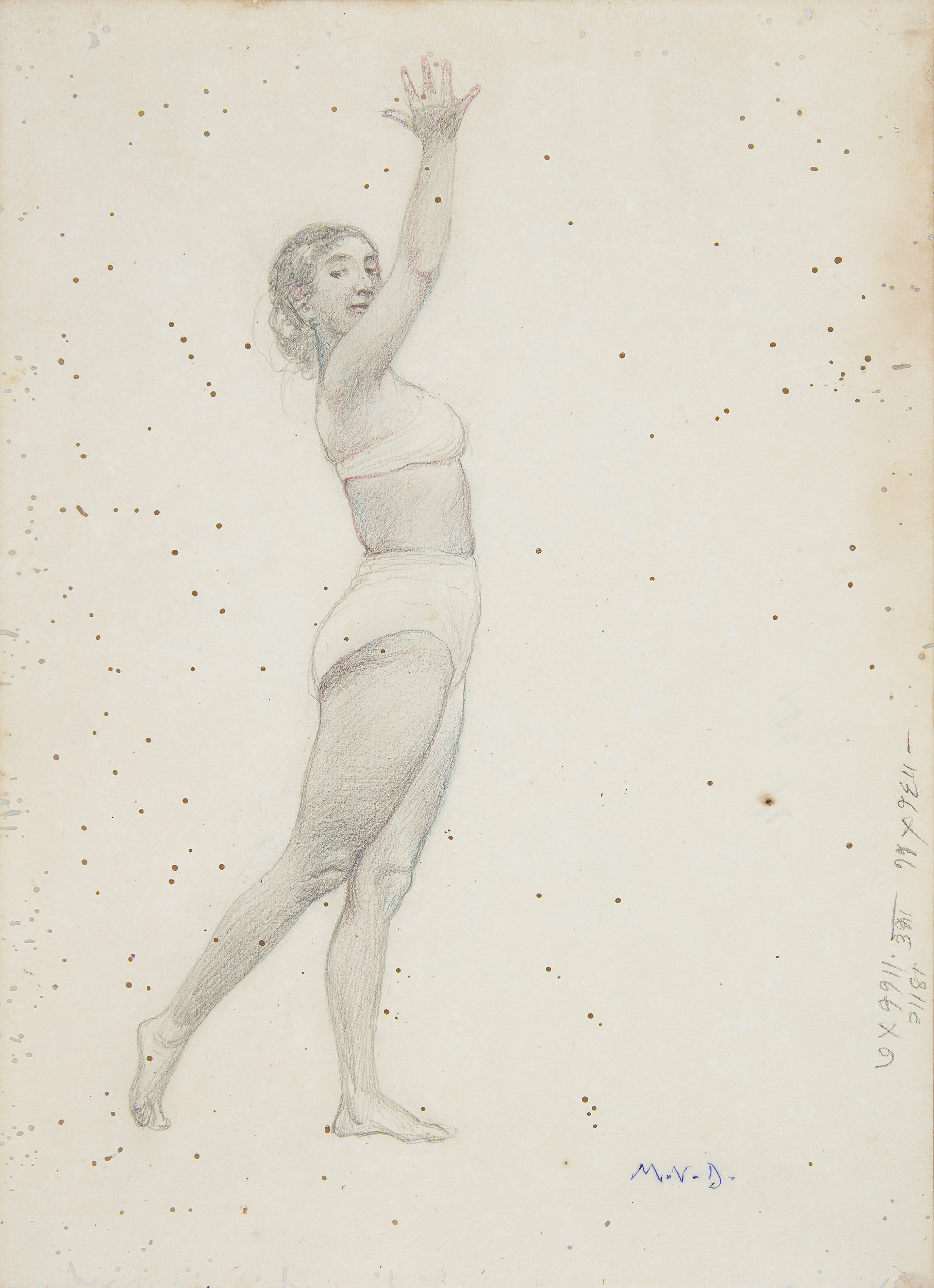

M. V. Dhurandhar

Untitled

Collection: DAG

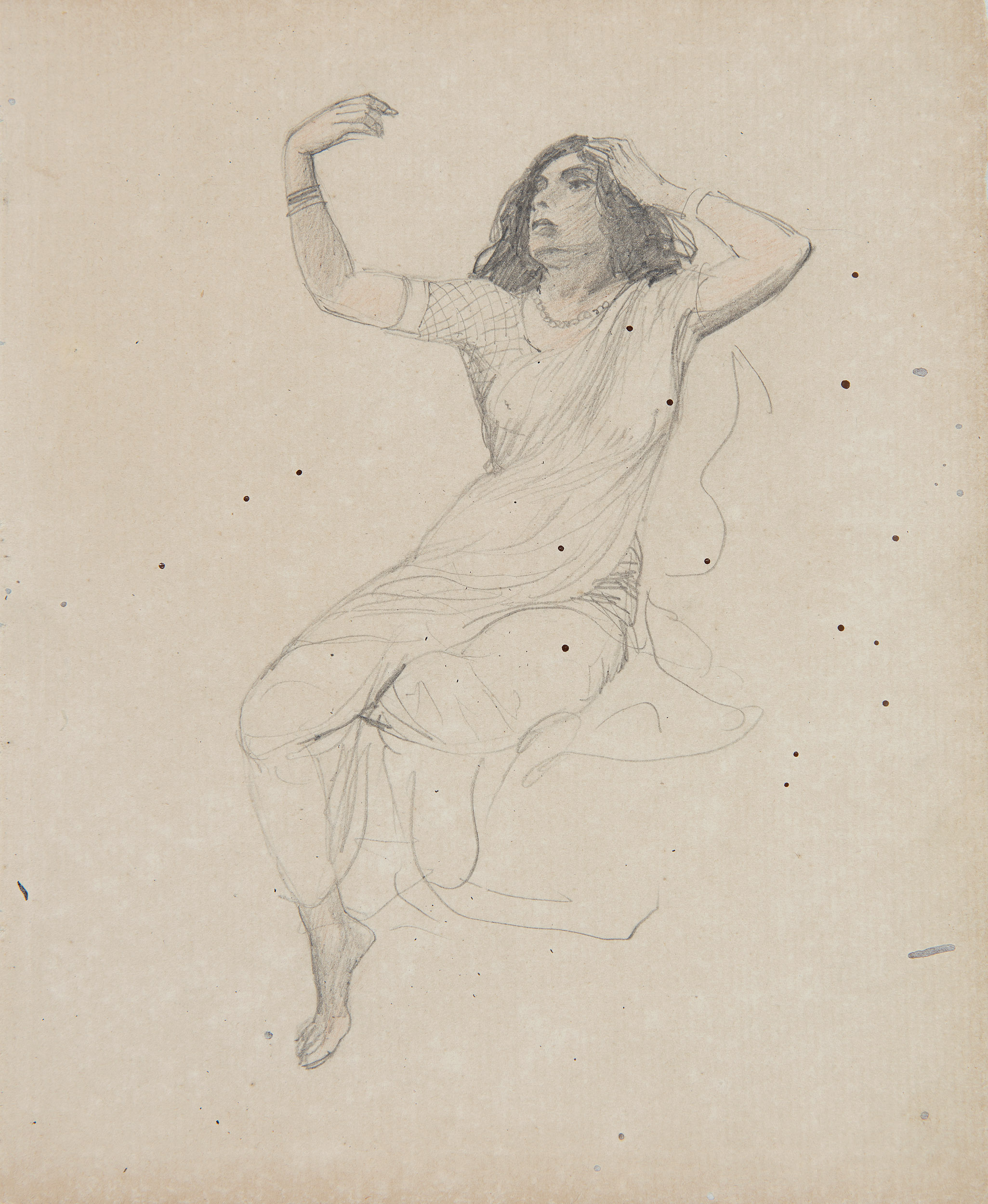

M. V. Dhurandhar

Untitled

Collection: DAG

Sir Thomas Lawrence

A Life Drawing

Black chalk, red chalk, and white chalk on medium, slightly textured, cream wove paper, 34.3 × 24.1 cm. ca. 1789

Image courtesy: Yale Center for British Art (Public Domain)

In India, the institutional practice of figure drawing follows established tradition as recorded in the history of the J. J. School of Art in Bombay (now Mumbai). M. V. Dhurandhar, one of the school’s most prominent alumni as well as faculty, excelled at what was at once a romantic and realist depiction of the human figure. Figure drawing classes would usually involve students surrounding a posing model as they sketched, each having a unique perspective due to their position and view—a practice that has been common throughout institutions for centuries. Dhurandhar’s model sketches, mostly of women (as was the norm in figure drawing after the Renaissance), reflect the artist’s ability to capture a sense of grace in the body. |

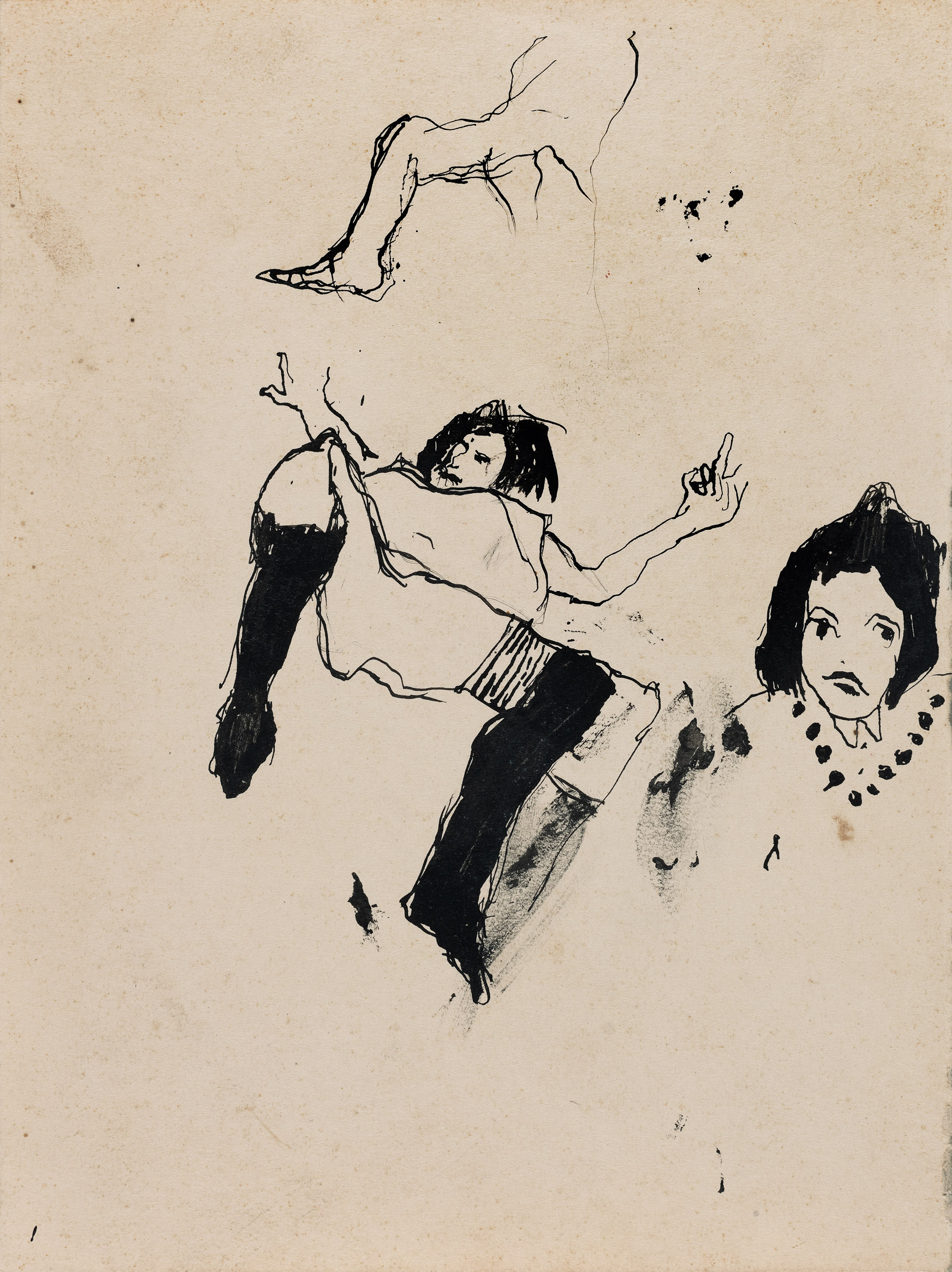

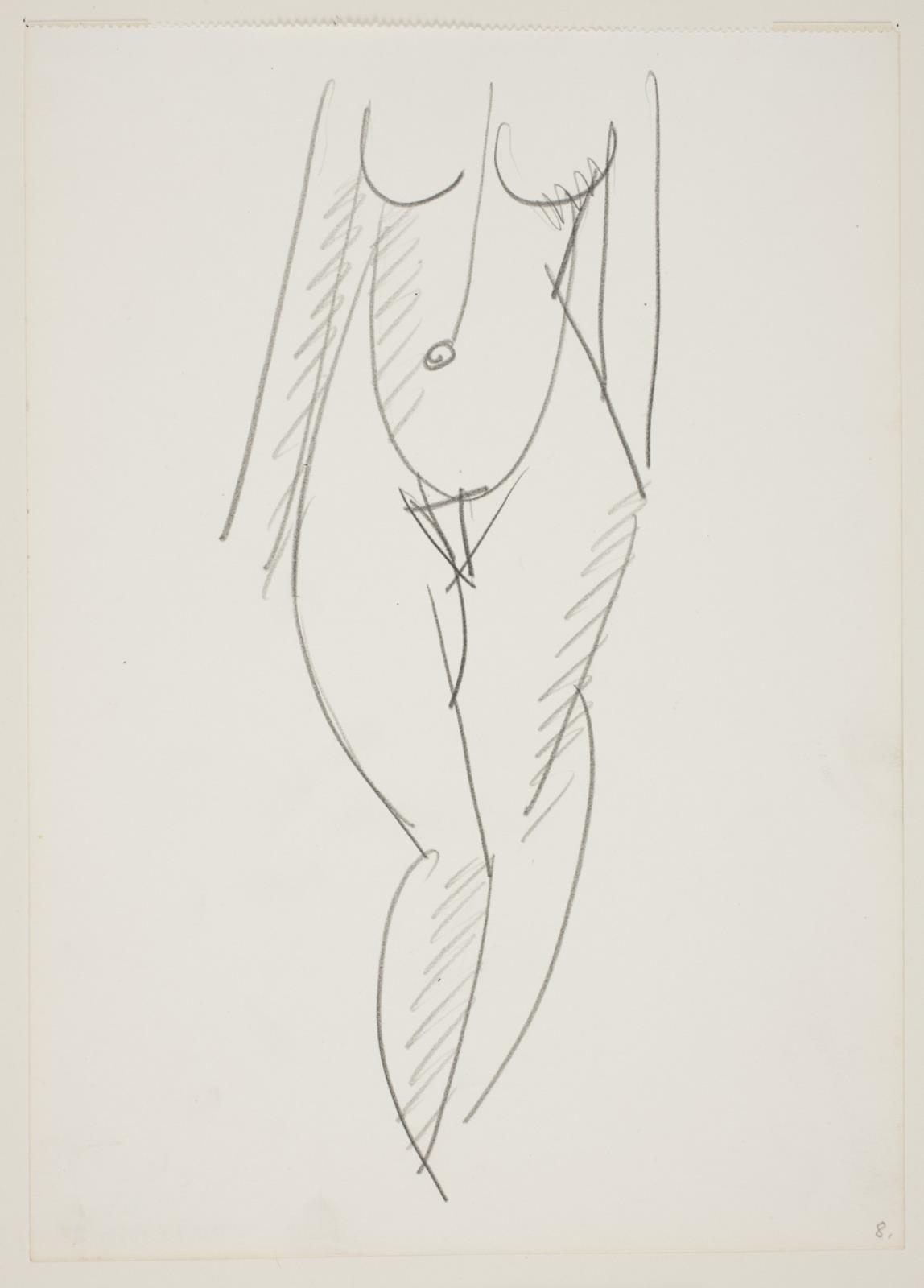

Altaf

Untitled

Ink on paper, 9.5 x 7.2 in.

Collection: DAG

Altaf

Untitled

Collection: DAG

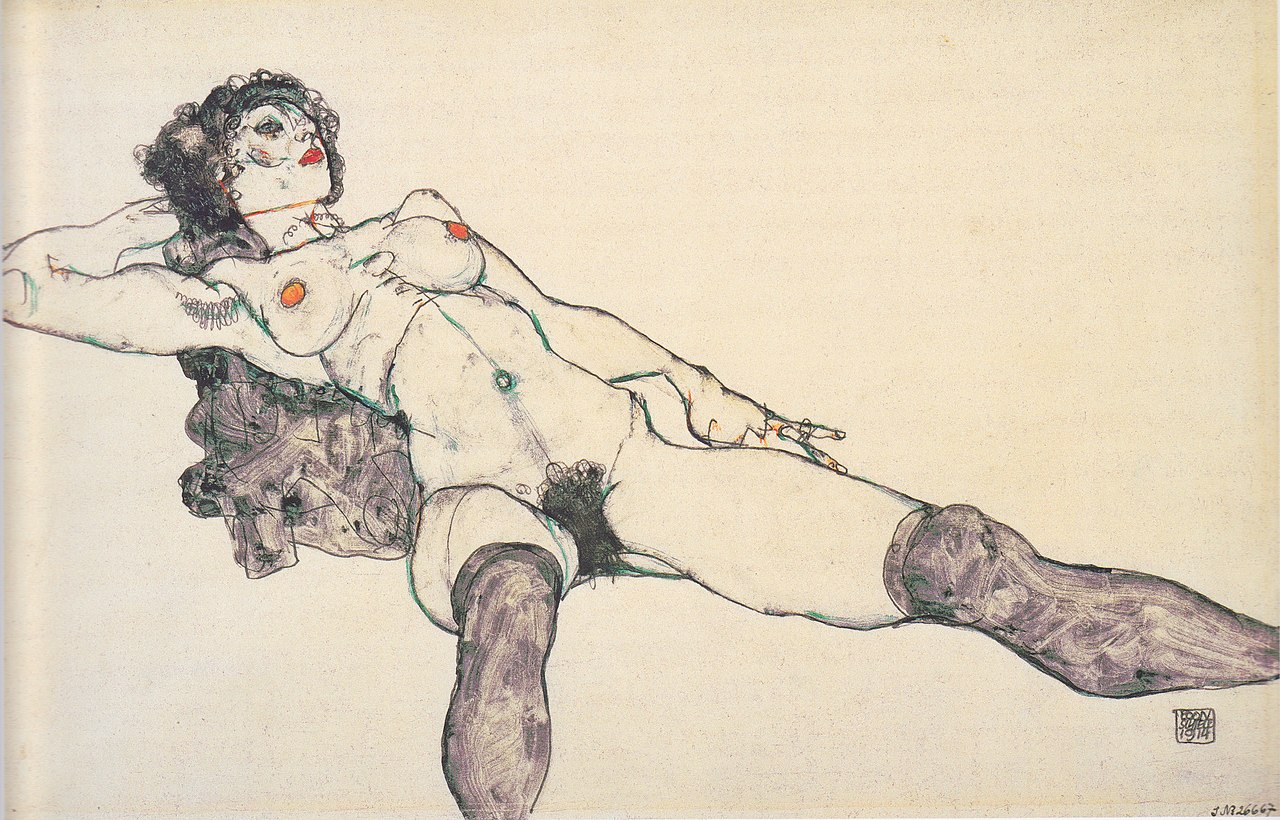

Egon Schiele

Liegender weiblicher Akt mit gespreizten Beinen (Lying female nude with spread legs)

1914

Image courtesy: Wikimedia Commons

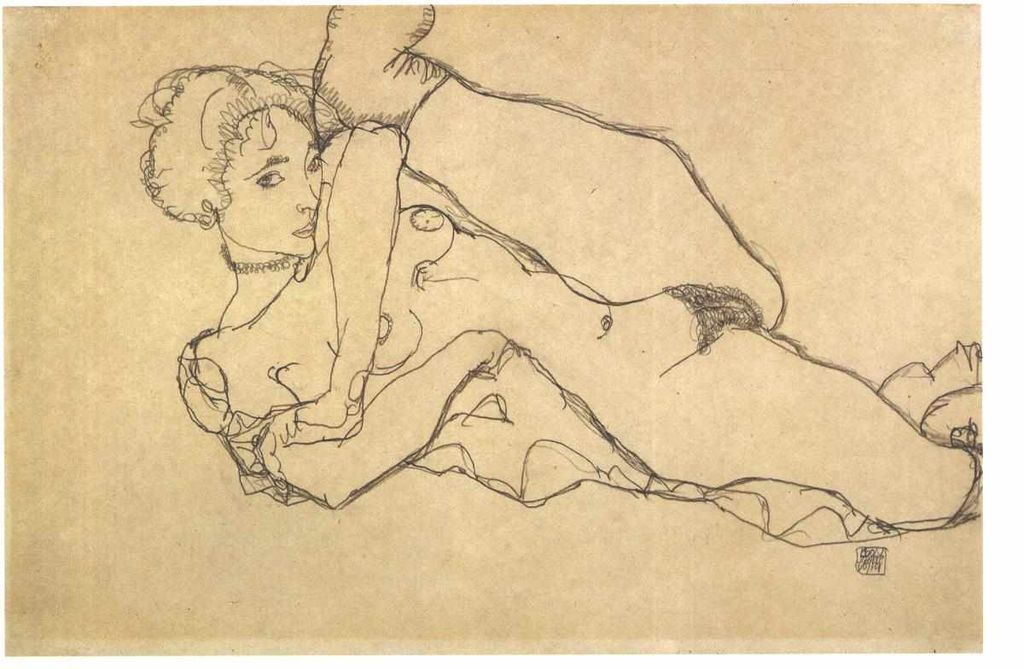

Egon Schiele

Lying female nude with raised left leg

1914

Image courtesy: Wikimedia Commons

Figure drawing, especially life drawing, endures well into and beyond modernity as both fundamental to art pedagogies and practices with variations in mode and approach. Nineteenth and early twentieth century artists such as the expressionist Egon Schiele, move on from faithful realism to figure drawings that privilege intensity and raw sexuality abandoning the quest for the ideal. His nudes are celebrated even today for their unfettered expression of sexuality. In India, half a century later, Altaf’s croquis (quick sketch of a live model) and raw figure drawings are stylistic inheritors of Dhurandhar’s realism and Schiele’s expressionistic nudes respectively—evidence that figure drawing is a methodological space of experimentation for artists transcending styles, trends, and schools. Altaf and Schiele’s experimentation with posture often adds a layer of psychological complexity despite the somewhat straightforward recognizability of the human form. |

|

‘First we visited the Marlborough Art Gallery, which exhibited the works of an Austrian painter – Egon Schiele. This painter lived during the years of the First World War, and I call him ‘young’ for he died young. Committed suicide. It is long since I have showed an over enthusiasm for an exhibition, but Schiele surely aroused my emotions. This young painter had an unbelievably intimate relationship with form and colour. True, his work shows an influence of both Modigliani and Soutine – to a lesser extent, both who are limited to their own style; but Schiele experiments tirelessly. What really enthralled me were his drawings – very subtle yet so strong and imposing.' -Altaf, The Journals 1963-1973 |

|

|

Pablo Picasso

The Frugal Repast

etching (zinc), 46.3 x 37.7 cm. 1904

Image courtesy: Wikimedia Commons

Vilhelm Lundstrøm

Stående nøgen kvinde set forfra

1945-48

Image courtesy: Public Domain

Vilhelm Lundstrøm

Stående nøgen kvinde set forfra

1943 – 1946

Image courtesy: Public Domain

F. N. Souza

Untitled

Collection: DAG

F. N. Souza

Untitled

Collection: DAG

Kenneth Clark writes, ‘Picasso has often exempted [nude drawings] from that savage metamorphosis which he has inflicted on the visible world and has produced a series of nudes that might have walked unaltered off the back of a greek mirror.’ Picasso’s ouvre indeed boasts of figure drawings of the more classical nature but also has cubist renditions of the human body stylistically similar to his cubist contemporary Vilhelm Lundstrøm. In India, F. N. Souza’s figure drawings from the 40s embody a sense of academicism with its soft contours and shadows capturing a kinaesthetic essence, but in the 50s moves onto a sense of abstraction with the focus on lines and angularity. |

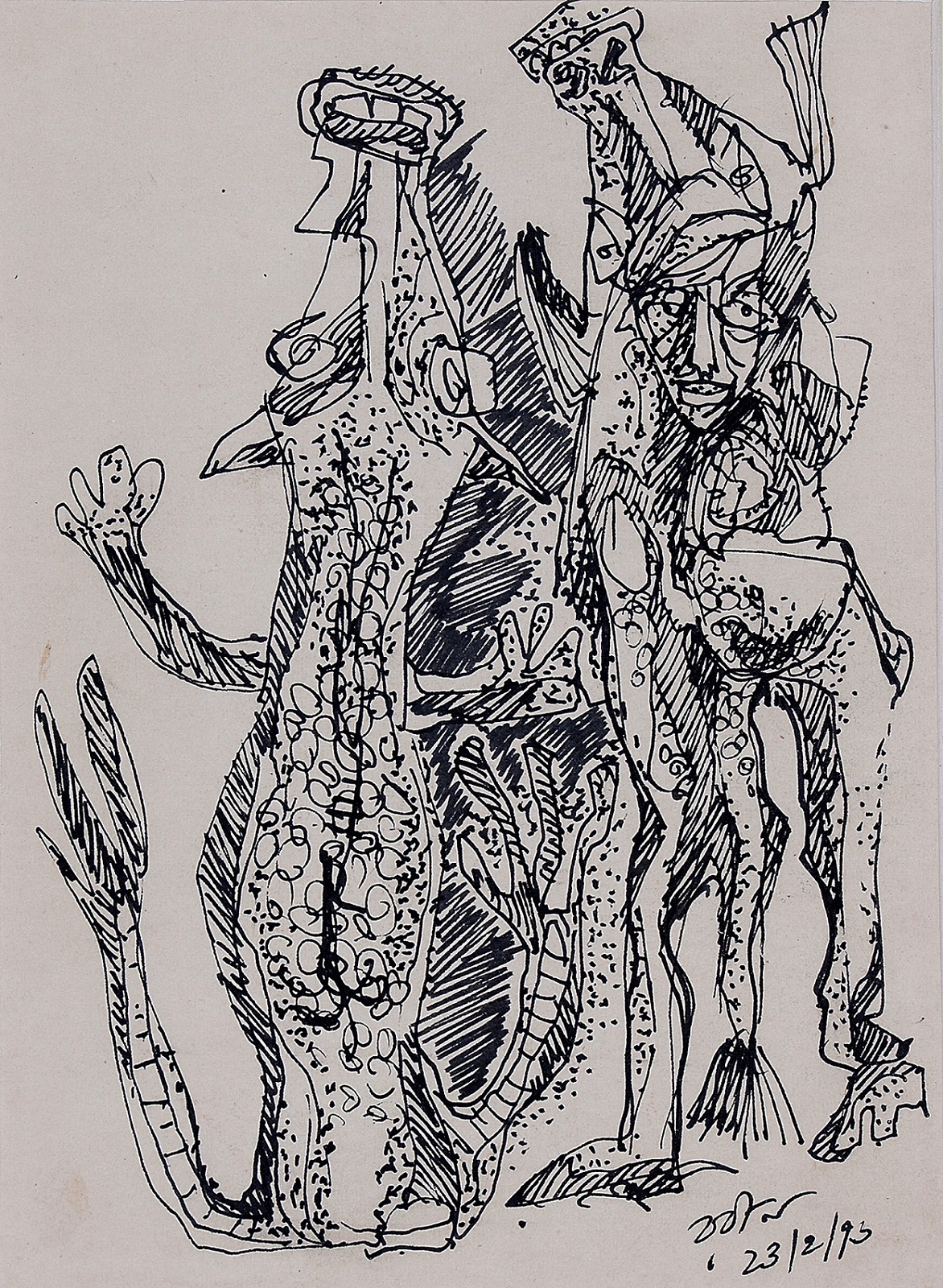

Rabin Mondal

Taking Over

1976

Collection: DAG

Moving beyond figure drawings that attempted to find ideal beauty or faithfully reproduce the human body, artists have abstracted the human body therefore disrupting our seemingly neat categories of figurative, abstract and representational art. Schiele, Altaf, Lundstrøm and Souza have all experimented with figure drawing in varying levels of abstraction. Intentional distortion of the human body to create visual metaphors for identity, society and the human condition, constitutes figurative abstraction. The question is, would figurative abstraction then be a subset of figure drawing? Rabin Mondal’s Taking Over has features resembling human ones—faces, hands, arms—all distorted and combined to create two figures. Formally, he employs techniques such as hatching (parallel strokes to create depth) and stippling (dotted shading), which are commonly used in more faithfully representational figure drawings. |

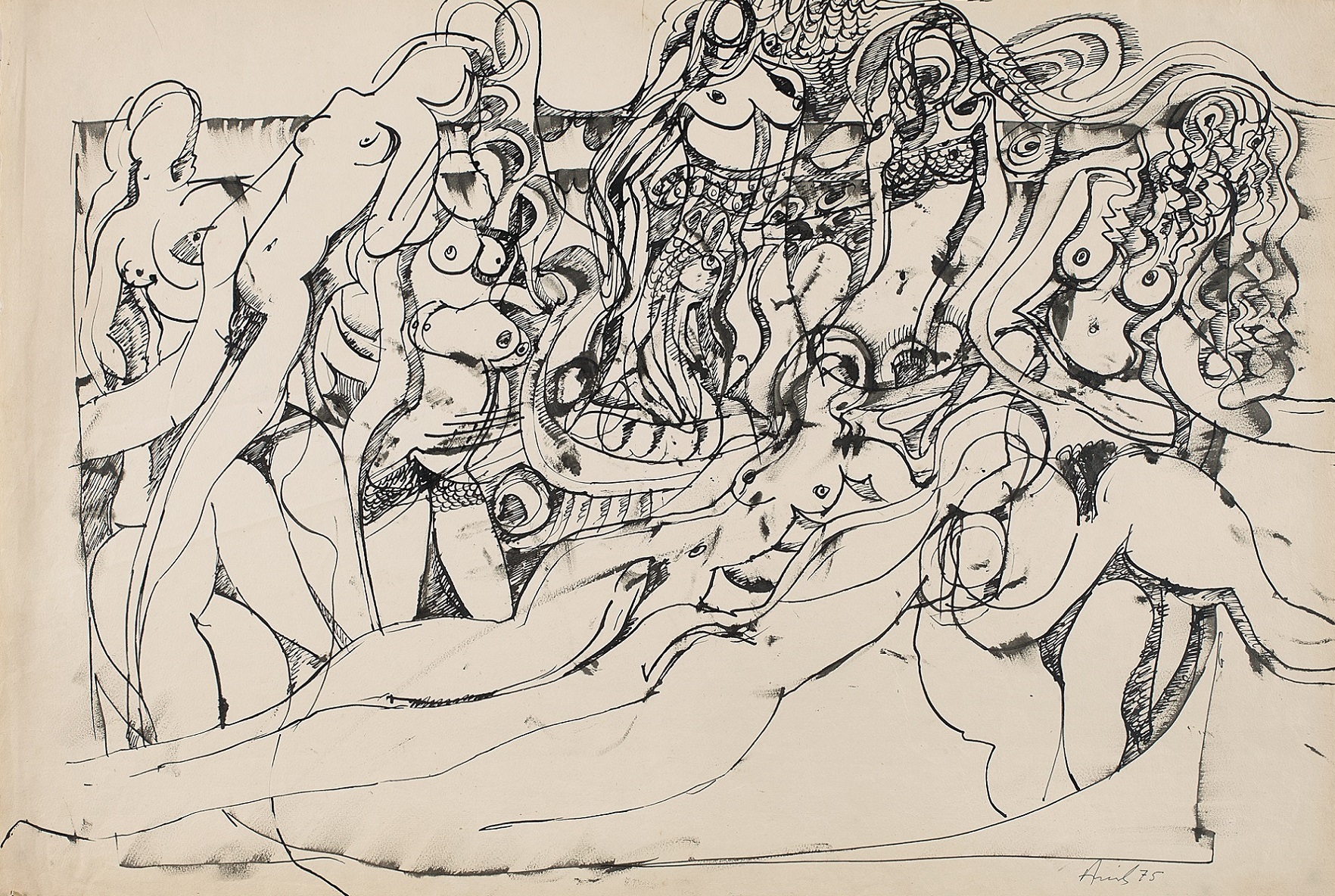

Avinash Chandra

Untitled

1975

Collection: DAG

In an untitled work from 1975, Avinash Chandra’s humanistic figures with breasts, torsos, hips, and legs resembling the female body create a landscape or humanscape that almost appear as a forest. Chandra had a unique approach to figure drawing where instead of sketching models from a distance he preferred the perspective of the model standing beside him as he sketched. He deploys his experiments with the methodology of figure drawing in these abstract humanscapes creating a formal medley that recurs in his visual language—illustrating the enduring presence of figure drawing in Indian modern art. |

|

Further reading:

|

|

|