|

Argot Term of the Month: EncausticShatadeep Maitra September 01, 2023 ‘Encaustic’ has the rare distinction of being a five-hundred-year-old old term from the sixteenth century that is still used quite popularly today. Who were the major practitioners of this complex process? We try to highlight some of the important aspects of this term in our recurring series, Argot, where we seek to demystify some of the major ideas from the world of art. |

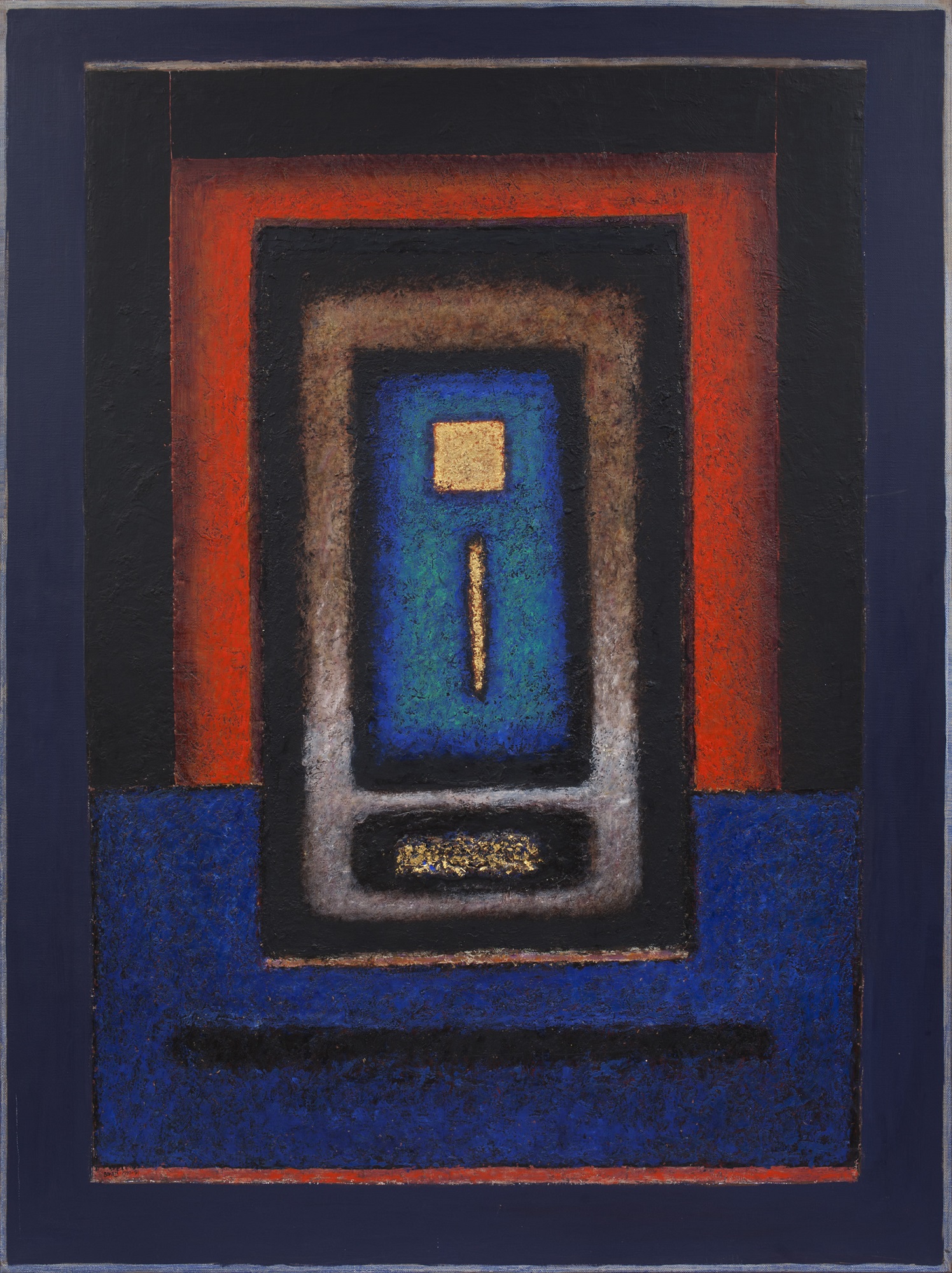

Eric Bowen

Font before the Altar (detail)

Oil and encaustic on canvas, 63.0 x 47.5 in., 1990-91

Collection: DAG

|

Paul Klee Image courtesy: Wikimedia Commons |

Mummy portrait of a young woman, 3rd century CE.

Louvre, Paris. Collection of Egyptian Antiquities of the Louvre; Department of Greek, Etruscan, and Roman Antiquities of the Louvre

Image source: Public Domain

It is derived from an even older Greek phrase, enkaustikos (conjoined from en and kaiein), which means ‘to burn in’. Ancient Greeks used heated beeswax to caulk or waterproof ship hulls. Parallel to shipbuilding, beeswax, or in instances clay, mixed with pigments, varnish, or resin, was used in artmaking processes—even though it was a much slower and laborious process when compared to tempera art as sustained heat was an essential component. Unlike tempera art, a relief surface could be built up by layering pigmented wax to create the impact of depth on an otherwise flat (two-dimensional) plane. The British Museum also houses encaustic mummy portraits from the first or second century CE. |

|

Jasper Johns Flag Image courtesy: Wikimedia Commons |

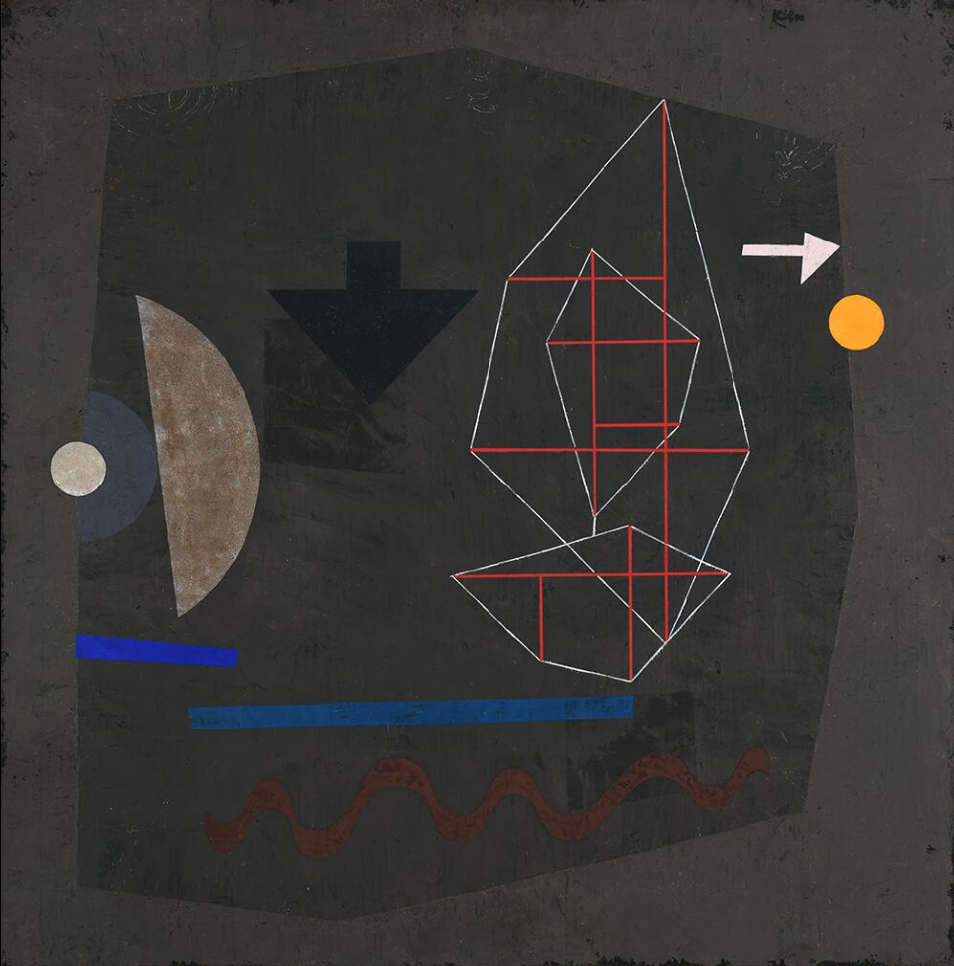

Paul Klee

Possibilities at Sea

1932

Image source: Wikimedia Commons

Jasper Johns

Flag

1954-55

Image source: Wikimedia Commons

The process of encaustic artmaking was revived in the twentieth century across the world. While looking Westward, notable artists who used this medium include Pablo Picasso (1881-1973), Diego Riviera (1886-1957), Paul Klee (1879-1940), and Jasper Johns (b. 1930). In the Indian subcontinent, none may surpass Shanti Dave (b. 1931) in the use of encaustic, who sustained it in his practice since the 1960s, and through the 1990s, with his last artwork in the medium being dated from the early 2000s. He started off by using paraffin wax before eventually finding a vendor in old Delhi who stored beeswax. |

|

‘After thinking through all the possibilities, I chose this encaustic medium. So that I could present its impact and impressions in an even more intense way. And for the texture that I wanted to bring out, I scratched or applied it with my hands and completed it.’ —Shanti Dave |

|

Shanti Dave Painting III 31.5 x 69.0 in., 1974 Collection: Priya Khanna, New Delhi |

Lateral view of Shanti Dave’s Painting III showing a detail of encaustic, from the exhibition, Shanti Dave: Neither Earth nor Sky at DAG, New Delhi

In 2017, the artist, when speaking to DAG, described his dedication to this medium: ‘Encaustic is not for everyone. For me, however, it gave immense satisfaction. I felt comfortable [and] at ease working in this medium. I could achieve so much more in art through perfecting this process.’ The difficulty of this art process comes across in another story Shanti Dave shared with DAG, which was published in the second volume of Iconic Masterpieces of Indian Modern Art. Once he had attempted teaching the encaustic process to his contemporary G. R. Santosh (one of the foremost artists of the neo-tantra movement), but Santosh accidentally ended up burning Dave’s entire kitchen by incorrectly mixing turpentine oil into heated beeswax. |

|

Shanti Dave Untitled Oil and encaustic on canvas, 67.0 x 118.2 in., 1974 Collection: DAG |

Shanti Dave

Untitled

Oil and encaustic on canvas, 50.0 x 50.0 in., 1968

Collection: DAG

Shanti Dave

Untitled

Oil and encaustic on plywood, 23.7 x 23.7 in., 1959

Collection: DAG

Dave’s use of encaustic grew in complexity with each decade. His earliest artworks comprise of broad swatches of pigmented wax that are shallower in comparison to the later, progressively intricate forms. From the 1970s onward, they start to resemble different aspects of life and civilisation: seemingly mobile organic and sinewy forms that stretch and contort across the canvas surface; inorganic shapes and structures mimicking topographical views of urban spaces; in addition to shapes that resemble anthropomorphic forms and vaguely familiar hand-written scripts. In such works, the elevation of encaustic increases as well, allowing for a comparison to relief sculpture. Perhaps this was an influence of Dave’s education in mural art. According to the art historian Jesal Thacker, ‘While exploring encaustic and the script you see a progression (in Dave’s work). From syllables they become symphonies, they become sound structures, they become script planks and architectural pillars—like an entire civilization in that one space. He is burning, he’s carving, he’s collaging; (he’s) sculpting it, and not necessarily just painting it.’ |

|

Sohan Qadri Collection: DAG |

Bimal Dasgupta

Untitled

Oil and encaustic on canvas, 34.0 x 34.0 in., 1964

Collection: DAG

Sohan Qadri

: Invocation-12

Oil and encaustic on canvas, 12.0 x 12.0 in., 1977

Collection: DAG

Eric Bowen

Font before the Altar

Oil and encaustic on canvas, 63.0 x 47.5 in., 1990-91

Collection: DAG

Among other Indian artists who utilised encaustic during the early post-Independence decades, we see works by Sohan Qadri (1932-2011) and Bimal Dasgupta (1917-1995). While the encaustic-laden works by Dasgupta may be compared to his non-encaustic counterparts, those by Qadri are visually divergent from the later ink works on paper the artist popularly made in Copenhagen. |