Term of the Month: CubismMarch 01, 2024 Cubism, an avant-garde art movement pioneered by Pablo Picasso and Georges Braque in the early twentieth century, revolutionised traditional notions of representation in visual arts. Characterised by fragmented forms, geometric shapes, and the simultaneous depiction of multiple viewpoints, Cubism sought to capture the essence of objects rather than their literal appearance. Over the long course of the twentieth century, however, artists and historians have attempted to complicate the story of cubism—in terms of its ‘origins’, as well as its impact—by attending to forces outside Europe as well. How did cubism come to influence South Asian art? Read our term of the month to learn about the style. |

Prosanto Roy

Untitled (Deepavali) (detail)

1954, Watercolour on paper, 10.2 x 8.5 in.

Collection: DAG

|

By deconstructing and reassembling subjects into abstracted forms, Cubist artists challenged conventional perspective and explored new ways of interpreting space, time, light and reality. Through its innovative approach to composition and representation, Cubism paved the way for modern art movements and significantly influenced the trajectory of twentieth-century artistic expression, leaving an enduring legacy in art history. |

|

|

Jyoti Bhatt

Untitled

1957, Tempera on handmade paper, 15.0 x 21.7 in.

Collection: DAG

Even as its impact continues to reverberate across the course of modern art, questions are still being asked about the wide range of non-European artistic traditions that had influenced artists like Picasso and his contemporaries. From the consciously ‘primitive’ traditions of Africa and the South Sea and Pacific Islands, to the sophisticated world of Japanese prints, as European artists sought to escape the conventions of academic realism, they found sources of inspiration in other non-illusionistic traditions of picture-making. In its turn, the critical success of cubism would go on to inspire many artists from outside Europe. For many imitators, the practice was confined to reproducing the European methods locally; but for many critical practitioners it provided a vocabulary to access complex areas of their own artistic heritage that had come to be ignored for various reasons. Cubism, in this sense, became a wider, more capacious, process for cultural exchange, rather than a mere artistic innovation. |

|

‘While thinking of Cubism I was reminded of something. When the potter turns his wheel the centre appears to be simultaneously whirling and yet remaining still.’ (Nandalal Bose in a letter written to Asit K. Haldar, 1922) |

|

Asit Kumar Haldar The Man 1940, Watercolour and ink on paper, 8.7 x 5.7 in. Collection: DAG |

Gaganendranath Tagore

Untitled

Water colour and ink on paper

Collection: DAG

Some critics, like Stella Kramrisch, held Indian cubism to be a contradiction in terms, although her response to Gaganendranath’s cubist works (produced in the early 1920s) was largely positive, especially in its efforts to assimilate traditional approaches to this method, demonstrating that non-illusionist art had evolved complex procedures outside Europe as well. Soumik N. Majumdar writes, ‘she (Kramrisch) pointed out the expressive nature of Gaganendranath's Cubism wherein 'the turbulent, hovering or pacified forces of inner experiences' were projected in terms of planes, facets and cubistic forms. Kramrisch argued that despite the influence of such a 'foreign' form Gaganendranath had internalized the peculiar cultural experience of India by turning the interpenetrating order of vertical and horizontal units into an expressive 'three-dimensional context or emotional pattern'. Tagore’s experiments were also informed by contemporary scientific experiments with light, space and questions on the divide between animate and inanimate forms, a debate with underlying colonial tensions. These turns were partly informed by his association with and admiration for the work of the pioneering Indian scientist Jagadish Chandra Bose, who started the Bose Institute. The institute today holds a significant work by Tagore depicting Bose’s experiments with light. |

|

What were some of the differences between European and South Asian experiments with cubism? As Soumik N. Majumdar writes, ‘Elucidating the essential differences with the European Cubists, Stella Kramrisch brought to attention Gaganendranath's strength as a narrator through his own brand of Cubism and also his ability to soften Cubism's formal severity and often ruthless geometry with 'a seductive profile, shadow or outline of human form'. |

|

|

George Keyt

Untitled (Two Women Amid Plants)

1947, Oil on board, 48.0 x 65.0 in.

Collection: DAG

George Keyt (1901-1993) was a renowned Sri Lankan painter known for his unique artistic vision that integrated traditional Sri Lankan aesthetics with modern techniques. His dominant style was influenced by Cubism, along with inspirations from ancient Buddhist art and sculpture. Keyt's work began to reflect the influence of cubism through the fragmentation of figures and objects in his compositions. He experimented with reshaping forms, breaking them down into simpler geometric components, and rearranging them in his paintings. He often flattened the picture plane and depicted multiple viewpoints simultaneously, similar to the Cubist approach, creating dynamic and multi-dimensional compositions. While Cubism is not primarily known for its colour palette, Keyt incorporated aspects of Cubist techniques into his use of colour and texture. He also adapted these techniques to explore themes and subjects drawn from elements of Sri Lankan culture, mythology, and folklore, creating a unique fusion of styles and themes. |

|

Many Indian artists were influenced by the technique, besides Gaganendranath, and it continued to inform their work into the decades beyond the 1940s. |

|

|

Paritosh Sen

Untitled (Portrait Cubist de Femme a la Cruche)

1952, Oil on canvas, 25.5 x 19.7 in.

Collection: DAG

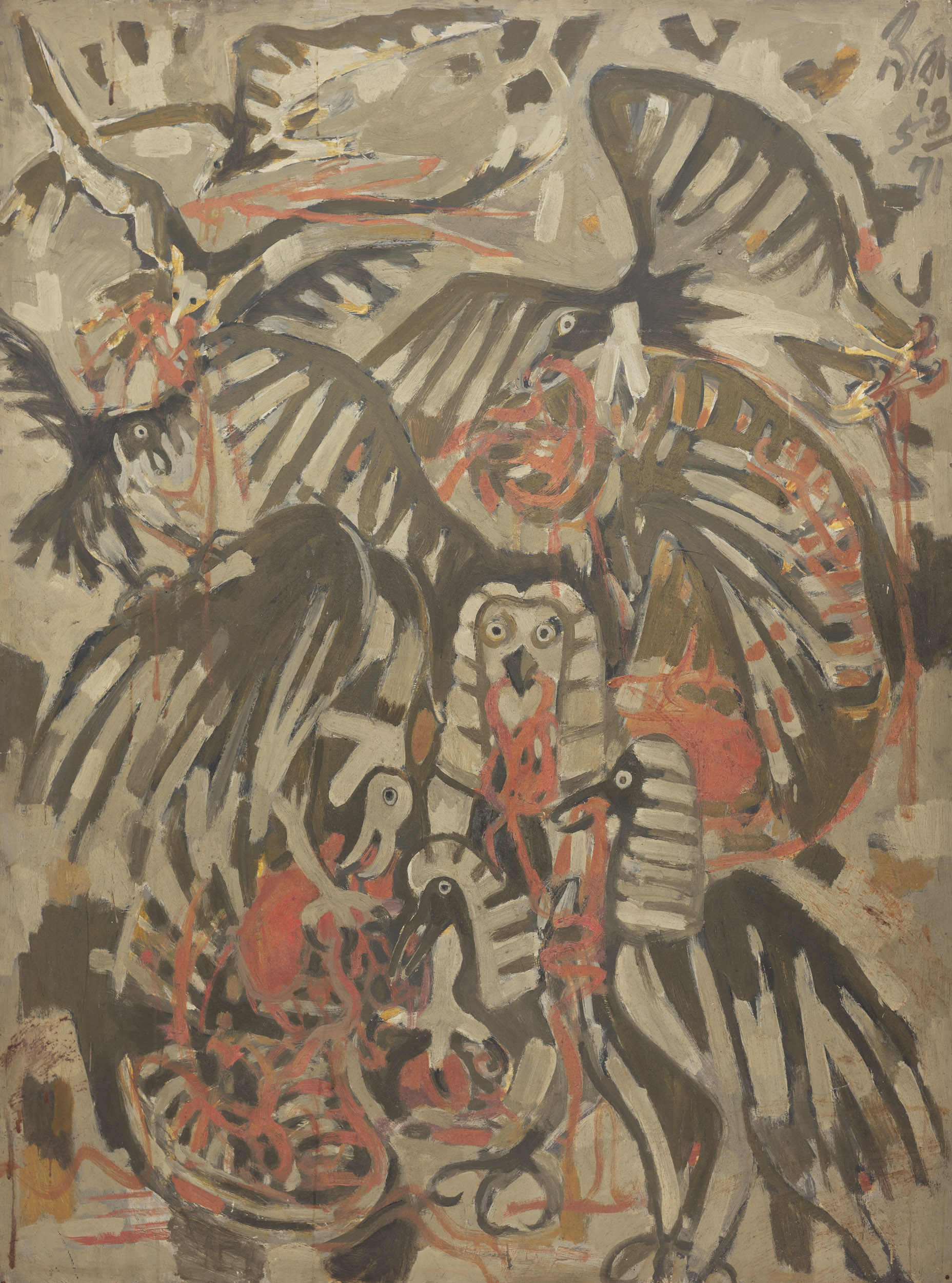

Nirode Mazumdar

Feast

1971, Oil on hardboard 48.0 X 35.7 in.

Collection: DAG

Nirode Mazumdar

Chandamari / Taking the King Snake Karakat

Oil on canvas, 24.0 X 29.5 in.

Collection: DAG

Artists like Nirode Mazumdar and Paritosh Sen actively sought to integrate cubist methods into their work, at least during certain phases of their career. They had also travelled to study art in Paris, where Sen had met Picasso. Paritosh Sen incorporated cubist elements into his artwork by utilizing two-dimensional, structured planes while maintaining an illusion of volume and voluptuousness. Sen's unique style combined international Modernist idioms with specifically Indian subject matter, resulting in a distinctive blend of styles – not unlike Keyt’s. Nirode Mazumdar's art displayed a blend of geometric forms, opulent use of symbols, and a complex internal organization, often based on geometrical foundations. While in Paris, he had befriended many artists, including Georges Braque. His compositions often feature flattened perspectives, fragmented forms, and a dynamic interplay of geometric shapes. These elements echo the spirit of cubism, albeit interpreted through Mazumdar's unique artistic lens. Moreover, cubism's influence on Mazumdar can be discerned in his experimentation with form and space, as well as his exploration of the inner psyche and metaphysical themes—especially in works featuring the goddess Kali, whose destructive frenzy found uncanny resonance with cubism’s impulse towards dissolution and motion. |

|

Meanwhile, many Bombay artists also reflected the influence of cubism on their work. The Progressives, especially M. F. Husain and S. K. Bakre, made many works that can be described as cubist in their essence, with their experiments with geometric forms and the ongoing effort to integrate indigenous methods into this international signature. |

|

|

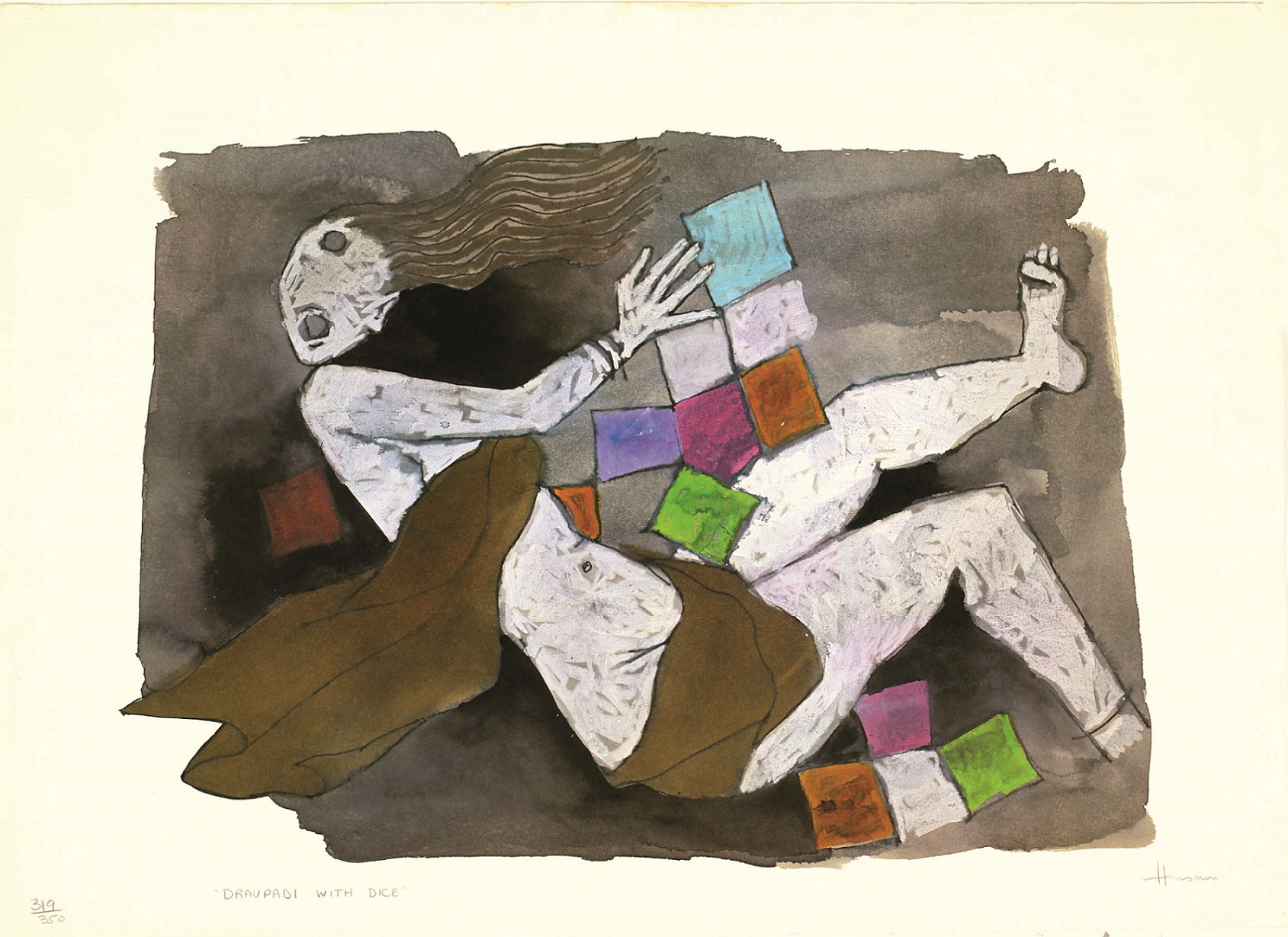

M. F. Husain

Draupadi with Dice

Mechanical reproduction on paper, 13.5 X 19.2 in.

Collection: DAG

M. F. Husain

Theorem II

1970, Oil on canvas, 47.5 X 47.5 in.

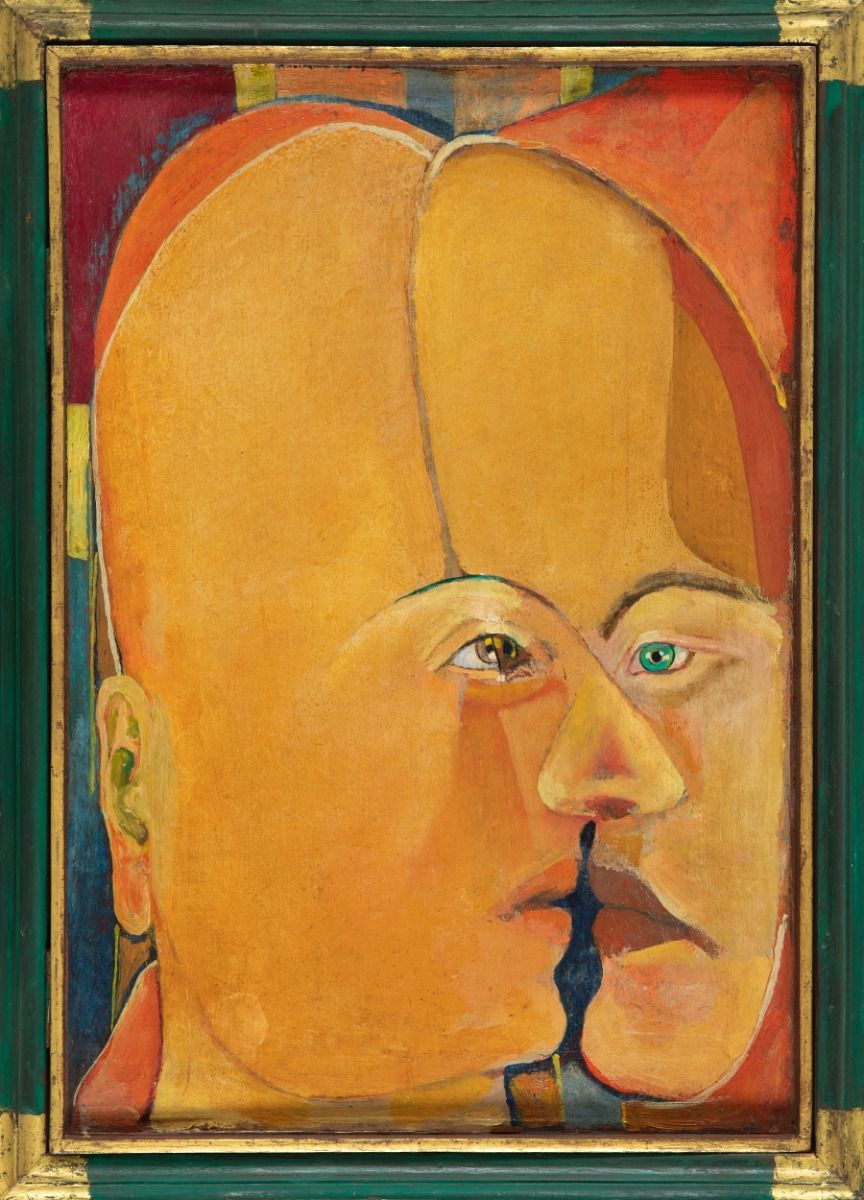

S. K. Bakre

Two Prophets in One

1998, Oil on plywood, 18.5 x 13.2 in.

Collection: DAG

Husain's early works demonstrate an unmistakable impact of cubism, evident in his compositional structure and manipulation of space. Furthermore, Husain's dynamic use of color and bold brushstrokes echoed the characteristics of cubism, contributing to his reputation as the ‘Picasso of India’. These influences were sometimes directly referenced by the artist’s use of geometric forms, like the dice he uses in his painting of Draupadi, or the use of the triangle in his work titled Theorem II. For S. K. Bakre, cubism provided a new visual language that he incorporated into his artistic repertoire. Bakre's work, particularly in his later years, showed elements of geometric abstraction and fractured forms reminiscent of cubist principles. He experimented with structure and form, infusing his compositions with a sense of dynamism and depth. In works like Two Prophets in One he merged two profiles to play around with the traditional tools of portraiture, fractured by perspective. |

|

These are some of the most well-known South Asian painters who used cubism as an influence on their evolving style. There were, of course, many more artists who used it, including Prosanto Roy. Although we saw how some critics tried to map the differences between European and Indian or South Asian styles of cubism, we have seen that it was not always easy to distinguish between the two processes, except in the near-ubiquitous use of indigenous forms or subject-matter. In Husain’s work, for instance, it would be difficult to argue that he always resisted the harder, geometric abstractions of European cubist art in favour of Tagore’s softer diffusions of form. Cubism wasn’t invented to bolster narratives, but the more brilliant South Asian artists found ways to infiltrate the form on their own terms—and they had their own stories to tell. |

|

|