Term of the Month: Calendar ArtAnkan Kazi January 01, 2024 The adoption of a standardized calendar in India was a significant aspect of the nationalist movement in the twentieth century. Before independence, India had a multitude of regional calendars based on various lunar and solar systems. The lack of a unified calendar system created confusion in administrative matters, public holidays, and cultural events. Indian nationalists recognized the need for a single, standardized calendar to promote national unity and cultural identity. One of the ways in which the idea of a unified calendar was disseminated to the masses was through the medium of ‘calendar art’. For our term of the month, we will explore the storied trajectory of calendar art in India. |

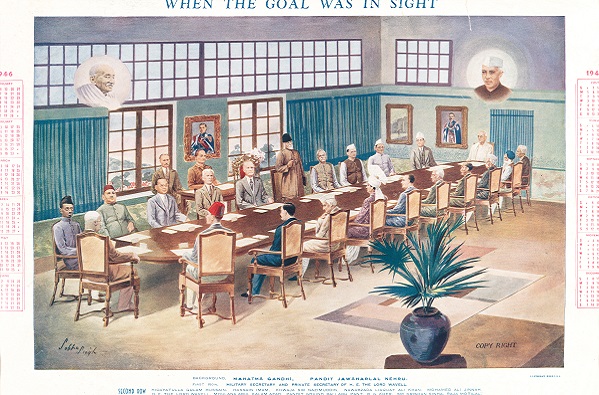

Sobha Singh

When the Goal was in Sight

1945, Offset print on paper, 33.0 x 47.5 cm.

Collection: DAG

|

In 1952, the Calendar Reform Committee was established to study the various calendar systems and recommend a suitable one for adoption. Meghnad Saha, a distinguished Indian Astrophysicist, served as the chair of the Committee under the auspices of the Council of Scientific and Industrial Research. The committee comprised other notable members, including A. C. Banerjee, K. L. Daftari, R. V. Vaidya, and N. C. Lahiri. It was through Saha's initiative that the committee was established. The primary objective assigned to the committee was the development of a precise calendar, rooted in scientific study, that could be uniformly adopted across India. To accomplish this, the committee undertook an extensive examination of thirty diverse calendars prevalent in various regions of the country. The complexity of the task was further compounded by the intricate connections of these calendars with religious practices and local sentiments. |

|

|

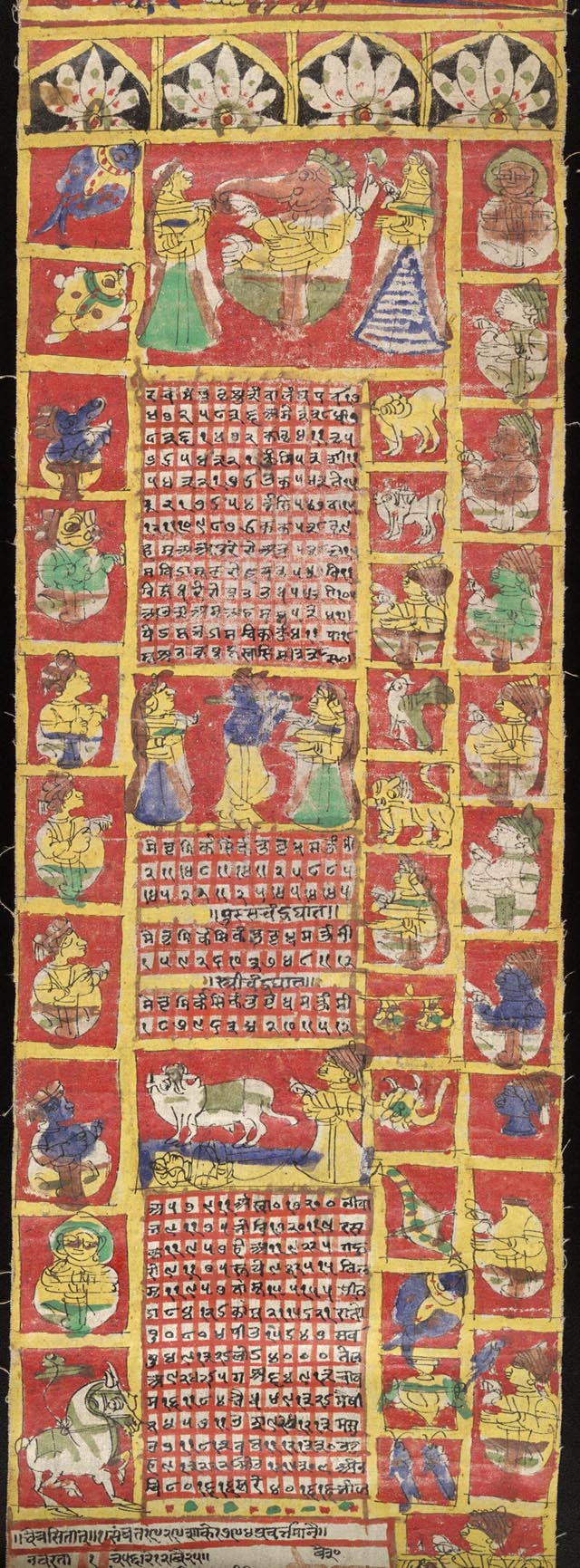

Fabric Hindu calendar/almanac corresponding to the western years 1871-1872, from Rajasthan

Image courtesy: Wikimedia Commons

National calendar prototype

Image courtesy: Wikimedia Commons

In 1957, the Saka calendar was officially designated as India's national, civil calendar. Grounded in the Saka era, commencing from 78 C.E., this choice was made due to its historical significance and cultural resonance with India. The Saka calendar had already been in use in certain regions of the country, particularly in historical inscriptions and manuscripts. Nevertheless, the adoption of the Saka calendar was not without its challenges. Intense debates and discussions transpired among scholars, politicians, and religious leaders regarding the selection of a calendar system. While some advocated for embracing the Vikram Samvat, another traditional Indian calendar, others lent their support to the Saka calendar. |

|

Although the term is contested by many publishers and printers of popular art, Calendar art in India has a rich and diverse history, evolving over the centuries to become a vibrant form of popular visual culture. The roots of calendar art can be traced back to traditional Indian miniature paintings and religious iconography. Over time, it has adapted to changing socio-cultural contexts and embraced modern influences. |

|

|

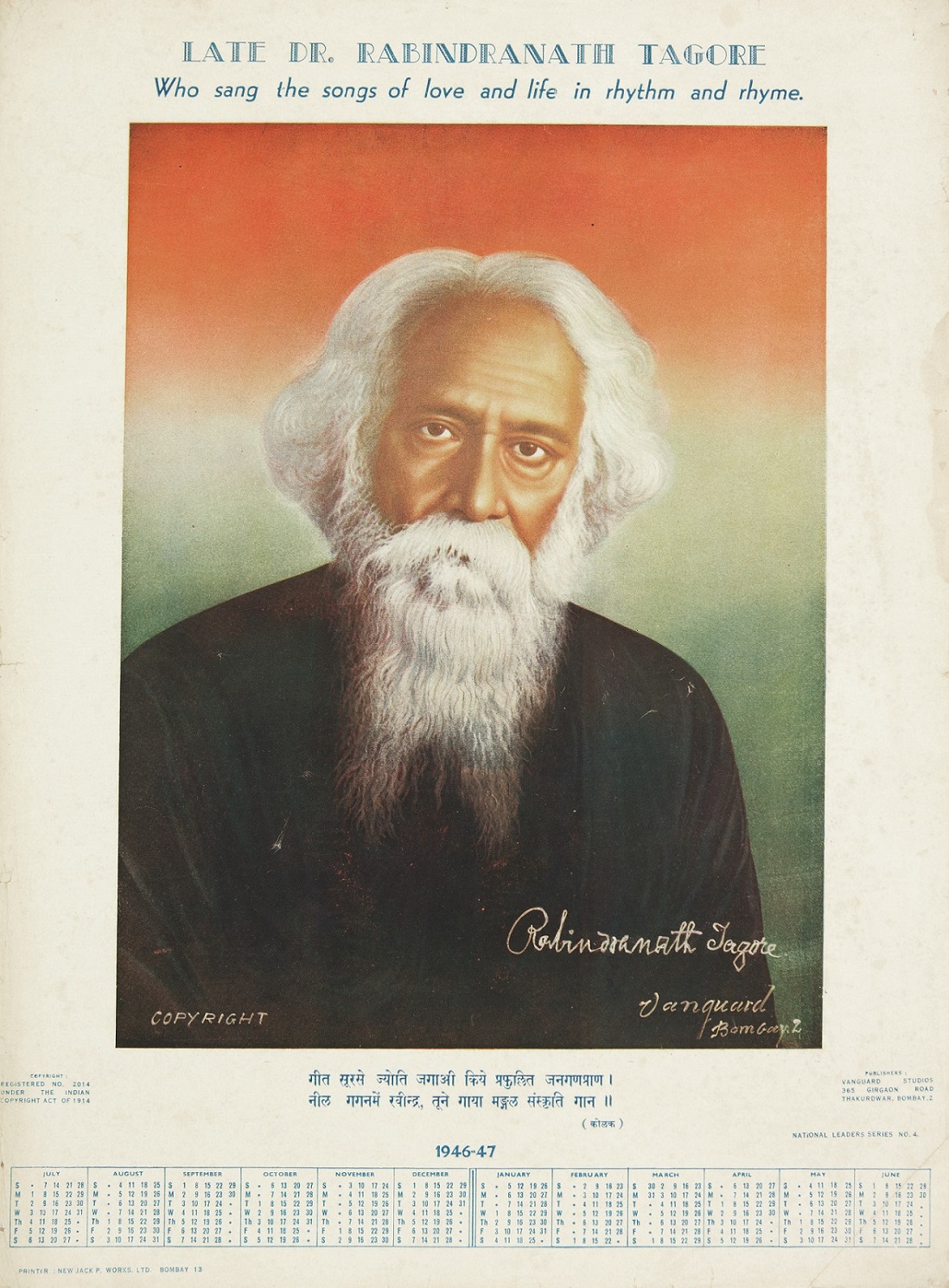

Anonymous

Untitled

45.0 X 36.1 cm.

Collection: DAG

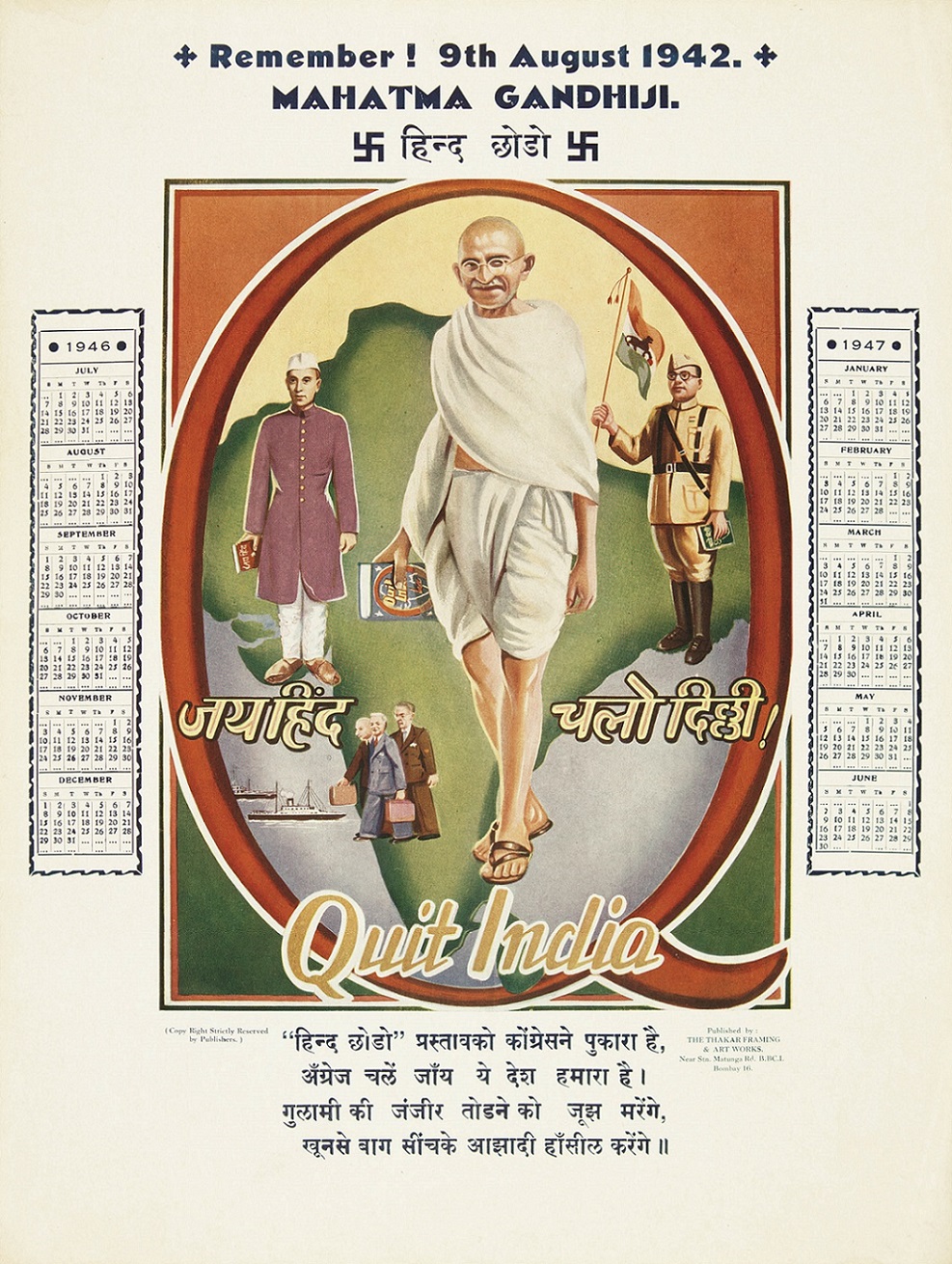

Anonymous

Untitled

66.0 X 38.1 cm.

Collection: DAG

The earliest forms of calendar art in India can be found in the religious scrolls and manuscripts that depicted mythological stories and religious events. These intricate paintings often adorned temples and palaces, serving both aesthetic and educational purposes. With the advent of print technology in the nineteenth century, the art form underwent a significant transformation. The late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries saw the emergence of calendar art as a mass-produced visual medium. European printing techniques were amalgamated with Indian artistic sensibilities, resulting in a unique style that catered to the tastes of a diverse and largely unlettered population. The calendar art industry flourished, producing images that ranged from depictions of deities to scenes from Indian epics and everyday life. |

|

One of the notable aspects of calendar art in India is its ability to bridge the gap between the rural and urban populations. It became a medium through which people from different backgrounds could connect with their common cultural and religious heritage, without limiting themselves to linguistic zones. Calendar art also played a crucial role in shaping popular perceptions of divinity and spirituality. The art form often portrayed gods and goddesses in a humanized form, making them more relatable to the common man. This aspect has been explored by scholar R. Siva Kumar, who notes, ‘Calendar art played a crucial role in democratizing access to religious imagery by presenting deities in a more accessible, humanized manner, thus fostering a sense of intimacy between the divine and the devotee.’ |

|

|

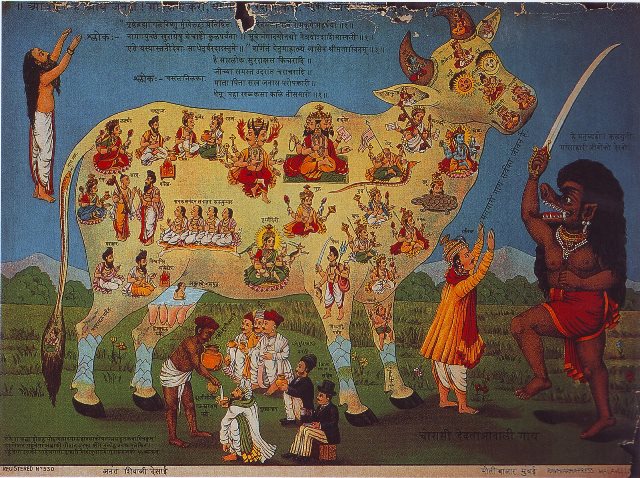

Image courtesy: Wikimedia Commons

Moreover, calendar art also constructed sacred symbols for popular devotion, such as the cow. Baisali Mohanty writes, ‘Aside from characters from Mahabharata and Ramayana, calendar art portrayed the cow as an immensely potent and sacred sign of Hinduism. The figure did not just function as a visual substitution but constituted a “gigantic simulacra” where the image of the cow had greater exchange value for its elevated representation than a prototype of God or nation would have. It was again calendar art that propelled the cow as a national symbol and informed the formal organisation as well the ideological basis of the cow protection movement in the late 19th century. B. C. Sharma was one of the first artists to produce a calendar image of the cow. His Milching a Cow, made in the 1880s, visually appropriated the ideology of the cow protection movement. It showed all the Hindu gods encompassed in a cow, while a woman milked the animal in the presence of small figures that can be identified as Hindus from their attire.’ |

|

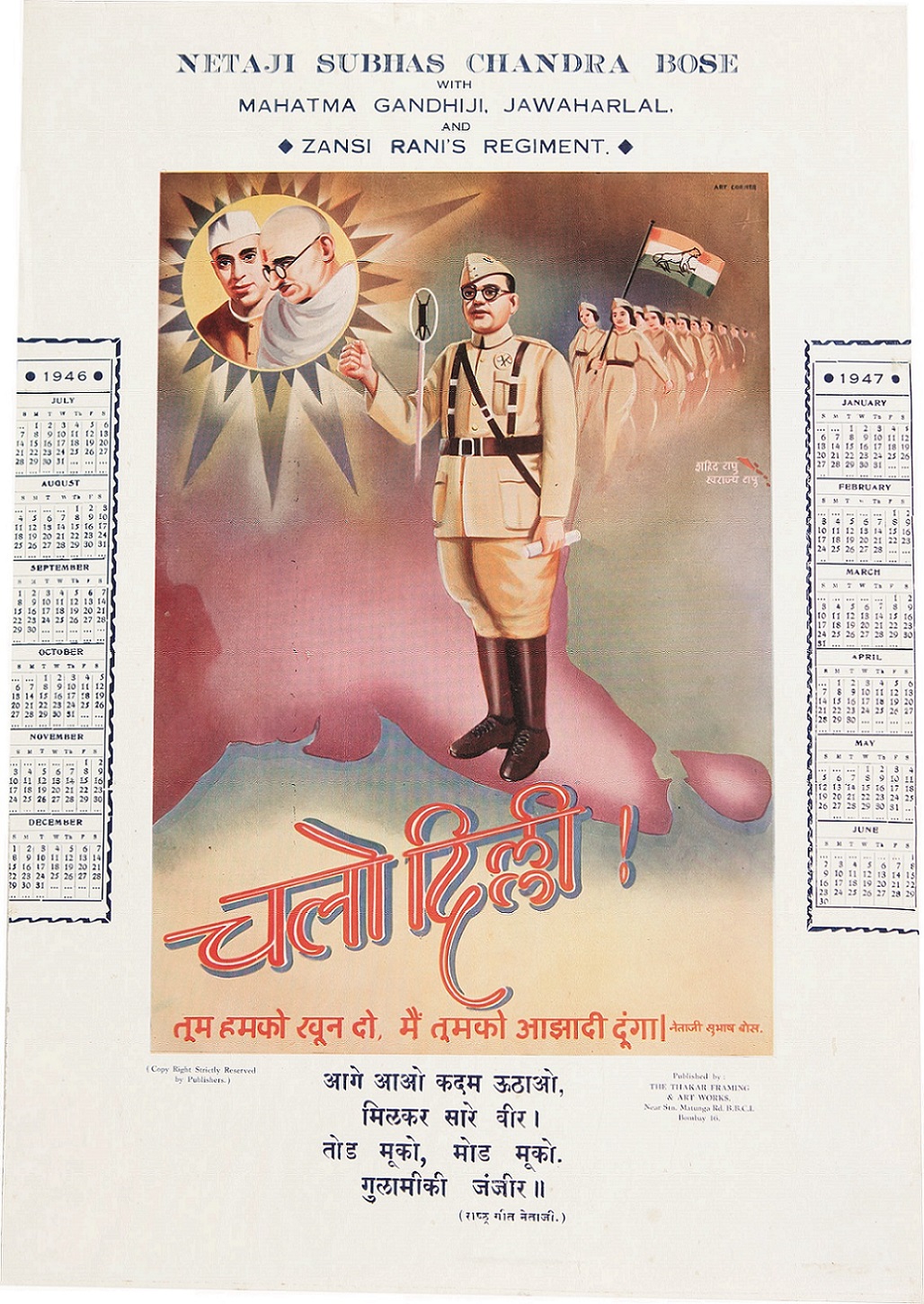

The mid-twentieth century witnessed a shift in the themes of calendar art, with an increased emphasis on social issues, nationalistic fervour, and secular subjects. The iconic images of Mahatma Gandhi and other freedom fighters started to make appearances, reflecting the changing political landscape of the time. This transition is aptly captured by art critic Geeta Kapur, who observes, ‘Calendar art became a visual record of the nation's journey, mirroring the socio-political and cultural changes.’ Images of famous literary celebrities like Rabindranath Tagore were also in circulation. |

|

|

Anonymous

Netaji Subhas Chandra Bose with Mahatma Gandhiji. Jawaharlal

Serigraph and offset print on paper, 47.0 X 34.8 cm.

Collection: DAG

Anonymous

Untitled

Serigraph and offset print on paper, 48.3 X 35.6 cm.

Collection: DAG

Since the 1990s, scholars in the academy have increasingly turned their attention to the aesthetic, political and economic aspects of popular art, including calendar art. Kajri Jain wrote a book titled Gods in the Bazaar: The Economies of Indian Calendar Art, which examines the power that calendar art holds in Indian mass culture. Jain argues that the meanings of calendar art derive as much from the social and economic contexts of its production and circulation as from its aesthetic content. Jain draws on interviews with artists, printers, publishers, and consumers, as well as analyses of the prints themselves, to trace the economies of art, commerce, religion, and desire within which calendar images and ideas about them are formulated. |

Anonymous

Untitled

Serigraph and offset print on paper, 45.0 X 34.8 cm.

Collection: DAG

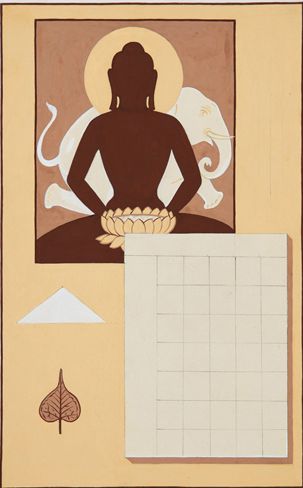

Muni Singh

Calendar design

25.9 X 16.5 cm.

Collection: DAG

Sobha Singh

When the Goal was in Sight

1945, Offset print on paper, 33.0 x 47.5 cm.

Collection: DAG

In contemporary times, calendar art in India continues to evolve, embracing a fusion of traditional and modern influences. Many Indian modernists, who worked on several commercial assignments throughout their lives, designed calendars and popular posters. Muni Singh (1936—1996), who sought to integrate miniature techniques in his art, designed several such calendars throughout his life. Although we know names of a few calendar and popular artists, such as Sobha Singh who made When the Goal was in Sight, most of these artists are unidentified, with some works possibly having been made by multiple artists. Artist signatures on calendar art is rare. Examples of iconic calendar art images include those of Hindu deities like Saraswati, Lakshmi, and Ganesha, depicted in vibrant colours and intricate details. Scenes from the Ramayana and Mahabharata, showcasing the heroic exploits of Rama and Krishna, are also common. Additionally, images depicting rural life, festivals, and scenes from Indian mythology remain prevalent, reflecting the enduring appeal and adaptability of calendar art in India. |

|

The history of calendar art in India is a fascinating journey that spans centuries, encompassing a variety of themes and styles. From its origins in traditional religious paintings to its role as a mass-produced visual medium, calendar art has become an integral part of India's cultural landscape, connecting people across diverse communities and preserving the country's rich artistic heritage. While you collect your new year calendars and map out the year ahead, do take a look at what the artwork in your calendar is trying to tell you about the times we live in! |

|

|