Art in the Class: A Behind the Scenes look at the T. F. I. and DAG collaboration

Art in the Class: A Behind the Scenes look at the T. F. I. and DAG collaboration

Art in the Class: A Behind the Scenes look at the T. F. I. and DAG collaboration

Art in the Class:

A Behind the Scenes look at the T. F. I. and DAG collaboration

Nandalal Bose, Soyna Randhche (detail), 1956, Ink on paper, 5.5 x 3.5 in. Collection: DAG

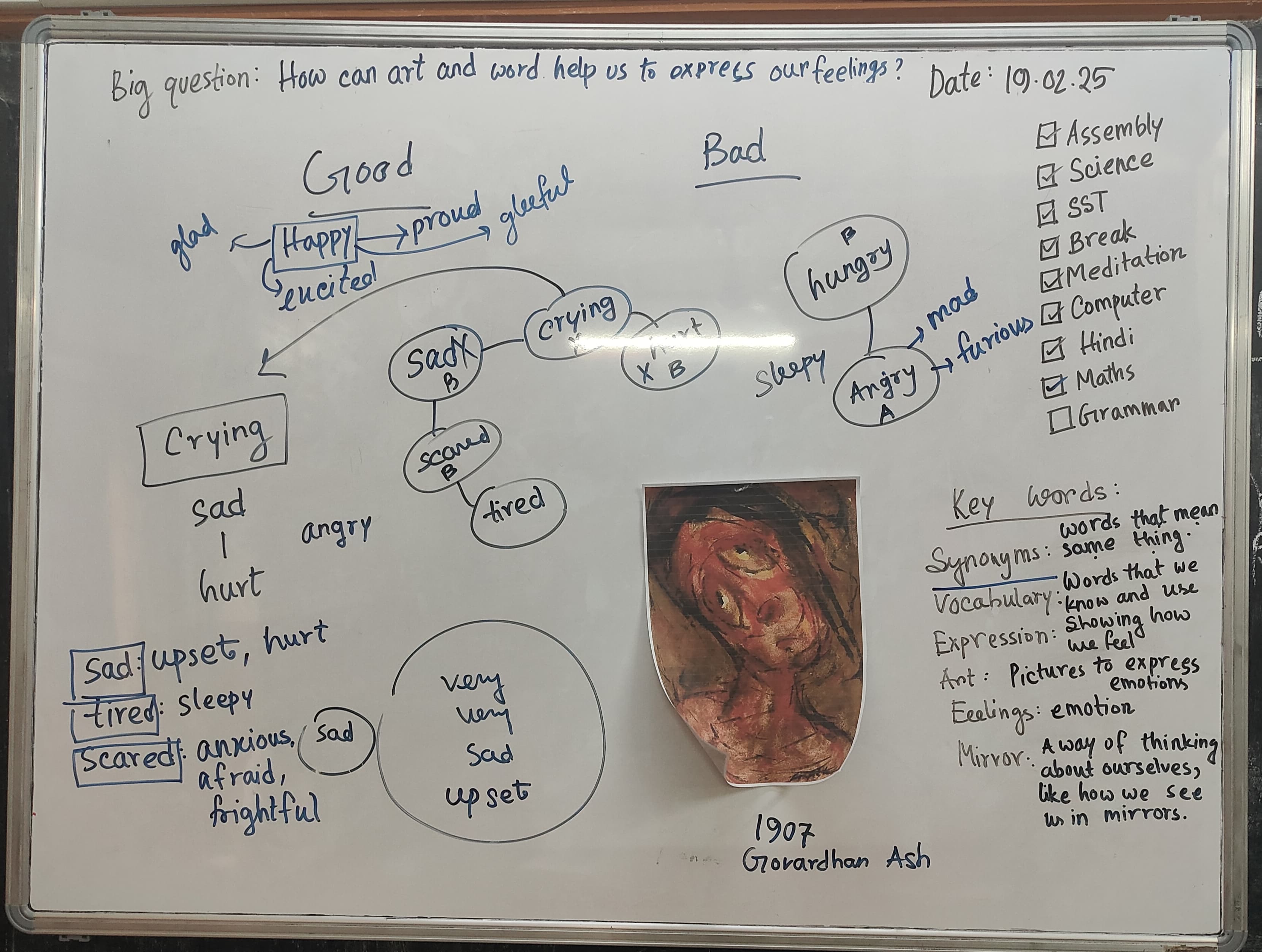

When Nipanjali was sticking Gobardhan Ash’s untitled watercolour on the board of the grade three classroom, a few students came in. ‘They immediately started calling the artwork scary and witchlike!' she recalled later, ‘Once they were provided with prompts to decode the artwork, they related it with pain, injury and smiling with sad eyes.’

|

Gobardhan Ash, Untitled, Watercolour on paper, 13.5 x 9.0 in. 1991. Collection: DAG |

Nipanjali is part of Teach For India’s Arts Track Fellowship with six other fellows, trying to make primary school learning engaging through visualising subjects. ‘Visualising learning is important as students can refer back to the visuals and make connections—unlike with text,’ said Nirajana another of the fellows.

A key component of the DAG Education programme for schools involves bringing artworks into classrooms, allowing students to become familiar with visual art and gain the confidence to interpret an artist's work. In our ‘Why is Art Weird’ workshop we had some of the most curious responses from sixth and seventh graders, looking at a work by Natvar Bhavsar and instantly connecting his colourful swirls to the dried pigments of Holi. Teach For India (T. F. I.) has been dedicated to driving innovation in the education sector with the firm belief that all students must attain an excellent education. Their methods and curriculum focus on providing students from low-income communities with a holistic education which includes fostering critical thinking skills and creative expression. The similarity of the way we imagine school learning, and our priorities of creating student-led classrooms practicing art-integrated methods of learning emerged as a realisation for both us and T. F. I. as we started imagining the possibilities in co-developing a module for primary school students from grade three onwards with the Arts Track fellows in Kolkata.

After a few fruitful conversations, we travelled to various T. F. I.-led classrooms around the city. It was a first for us to develop something for primary students, and as we stepped into the classrooms we realised how enthusiastic every learner across Alipore, Park Circus or Anandapur were to respond to critical questions about how gender mismatch in the classroom might have a larger social impact, for instance; while we went deeper into their English texts. Each step was visualised through illustrations—including Mathematical problems—and repeated for comprehensibility. Most classrooms were not digitally equipped and were very small spaces limiting much movement, but their walls were full of illustrations using unconventional materials, covering a wide range of topics, including mapping students’ emotions. Flipping through their textbooks, we also noticed chapters focused on understanding their own emotions and learning about the history of their city through significant buildings, traditional clothing, and local cuisine.

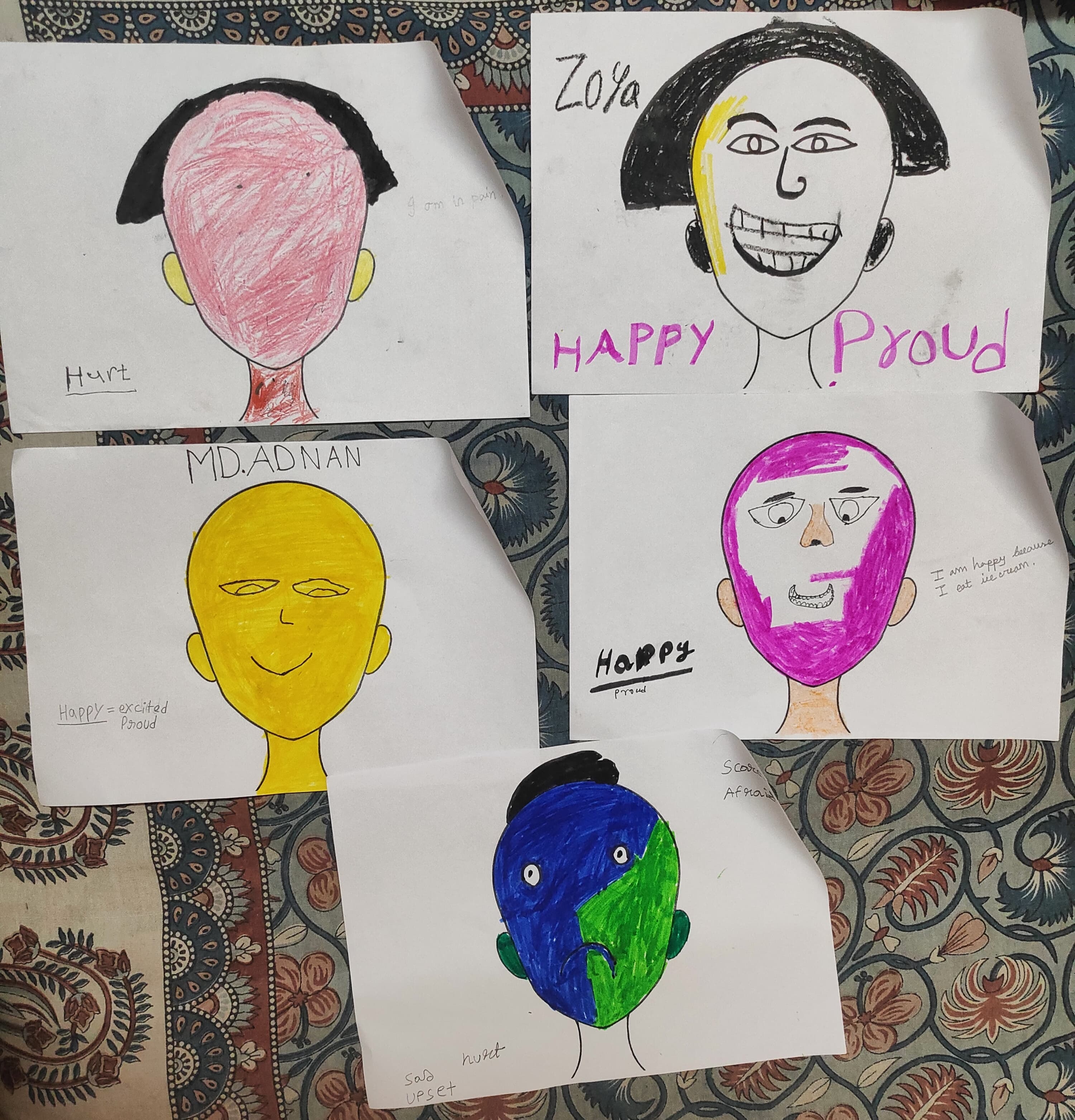

We then turned to the artworks in our museum collection that align with themes in the curriculum, allowing the fellows to teach these topics through art. As many of the fellows shared in our initial meetings, fine art was something they hadn’t had access to and, therefore, hadn’t typically incorporated into their lessons with students. To bridge this gap, we explored pieces from our collection that could be exciting, unfamiliar, and even thought-provoking for the students, sparking genuine responses. One such piece was Gobardhan Ash's watercolour of a figure with a tilted head and a curious expression. We imagined how students might enjoy interpreting her emotions in a context where there were no right or wrong answers, and connected the artwork to the third-grade social science chapter on Emotions. To round out the lesson, we included a Language lesson so students could not only identify and understand emotions but also learn to express their thoughts and feelings coherently. In discussions with the fellows about this module based on Gobardhan Ash's Untitled work, we began to see the emergence of a curriculum that focused on developing both observational skills and expressive abilities, encouraging students to draw inspiration from art while honing their capacity to articulate their ideas.

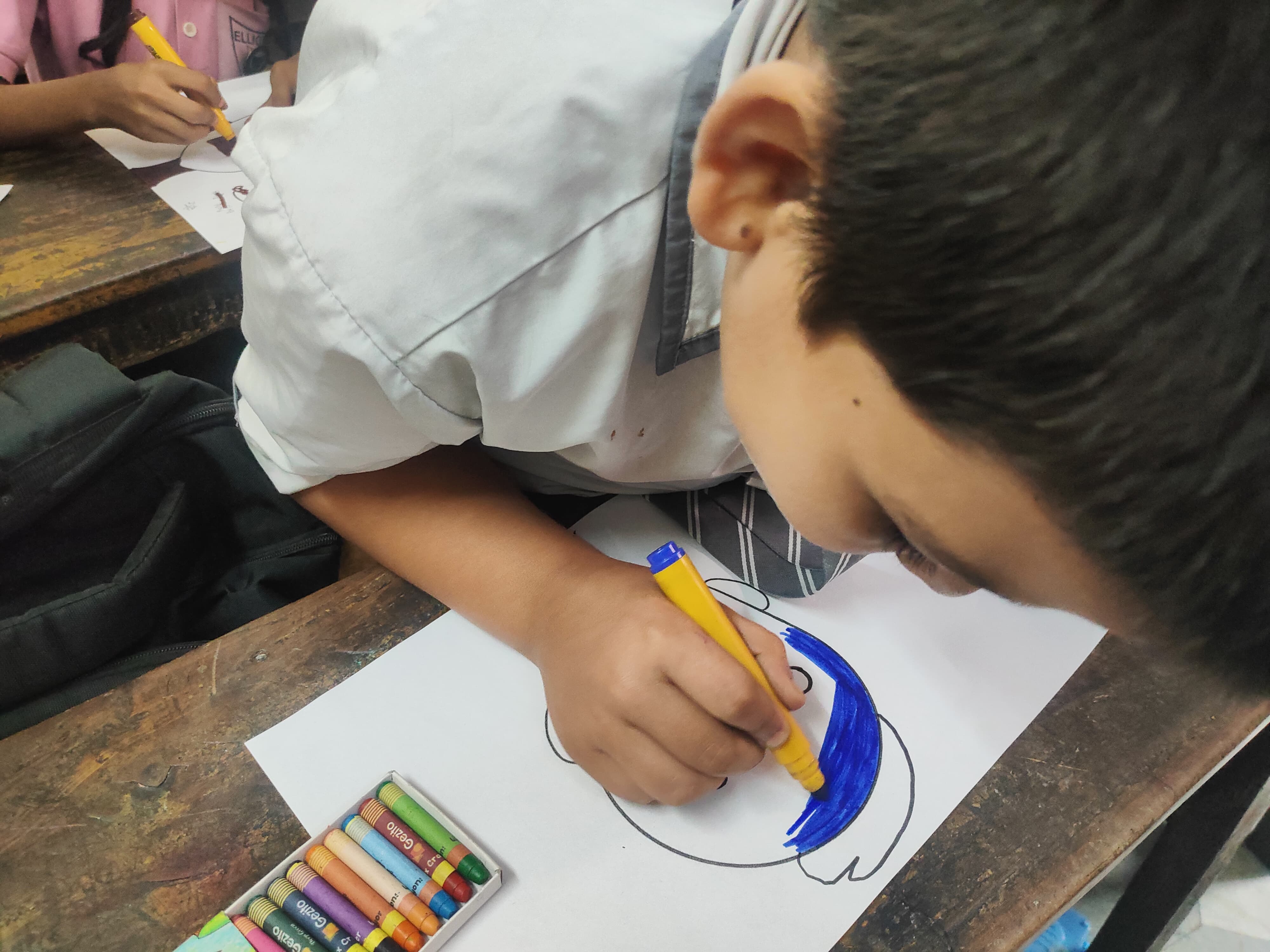

Over the course of several days, we met with the cohort of Arts Track fellows, sitting around a table to workshop activities using various artworks from our collection, exploring different possibilities and outcomes. While working with students at K. M. C. (Kolkata Municipal Corporation) schools, the fellows aimed to push students beyond the confines of their prescribed curriculum. This led us to develop a three-step process. First, students were given time to simply observe the artwork, encouraged to notice its details—especially in a time when image saturation often prevents us from truly focusing on a single visual for an extended period. By paying attention to elements like colours, lines, and the medium used, students began to recognise the image as a work of art created by an artist. This sparked discussions about the artists, most of whom were from Bengal, providing the students with valuable insights into local art practices.

To assess what students already knew and identify what still needed to be learned, the fellows took note of the words students used in response to the artwork during prompted activities. They then asked students to find connections between these words, helping them organise the information systematically. This process allowed students to interpret, synthesise, and apply the knowledge they had gathered. After all the discussions and board work, perhaps the most enjoyable part for both the fellows and the students were the interactive games created by the fellows. Whether it was stepping into the shoes of a bird in a kitchen sketched on a Nandalal Bose postcard or exploring gender through a flipbook, these activities provided a fun and engaging way for students to visually express themselves. The curriculum culminated in this creative exercise, allowing students to tie everything they had learned together.

'The students were intrigued and excited,' said Dishannesha, another fellow who had been trying out the methodology; adding that ‘it was a novel experience for them, so the questions came shooting right after’. Nipanjali echoed this, noting how students often ask insightful questions and retain a great deal when engaging with visuals like these. As we approach the final month of development, we’re excited to move forward with this as a standardised methodology for all T.F.I. Fellows to integrate into their existing curriculum.