|

Travel With Us Spirit of the Mountains: Visiting the Nicholas Roerich MuseumJosheen Oberoi and Ankan Kazi July 01, 2023 The Nicholas Roerich Museum in New York represents one of several such rich repositories on the life of the eponymous artist, spiritualist and writer from Russia. His peripatetic life in the early decades of the twentieth century led him across legendary journeys across the world, especially Central Asia and the diverse Himalayan landscapes of North India. What did his life in New York look like? And what impact did his vision have on American artists and intellectuals? |

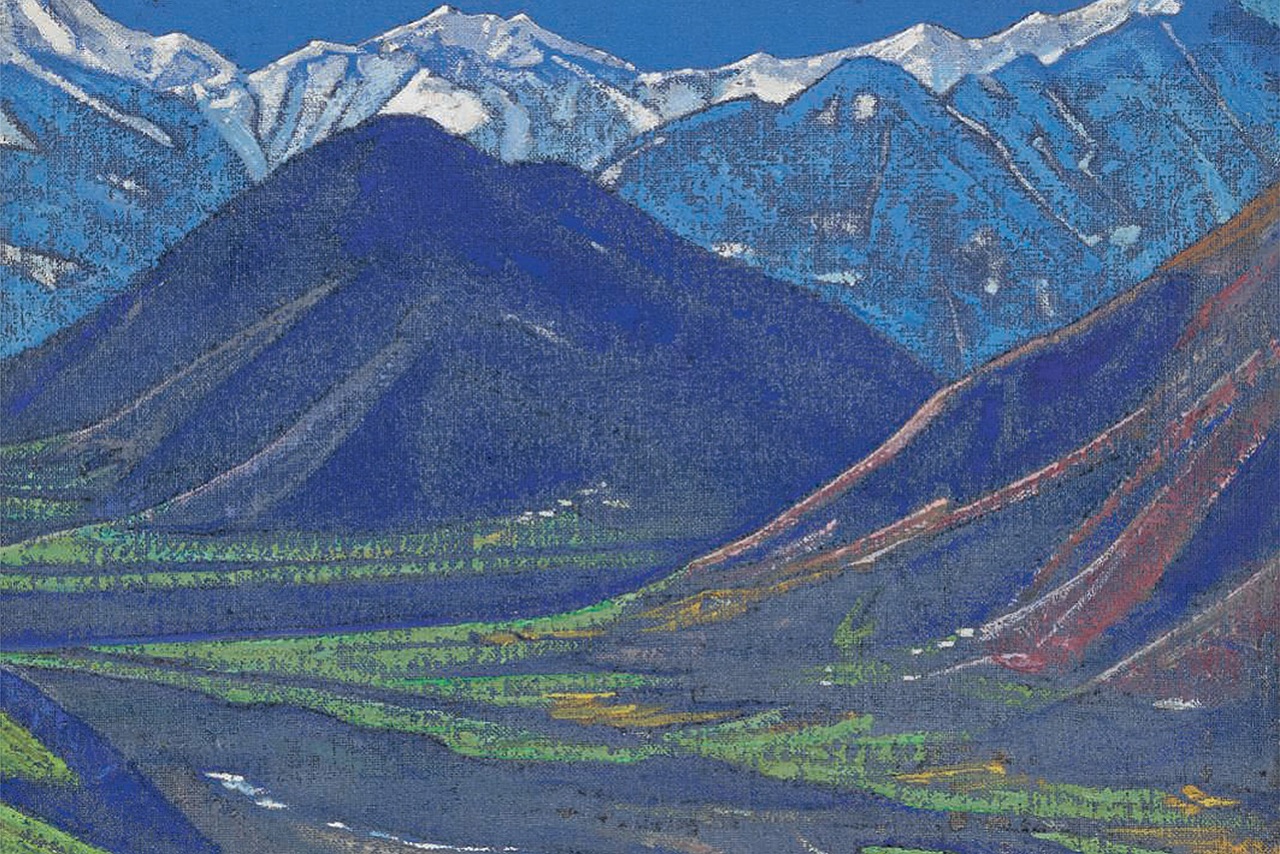

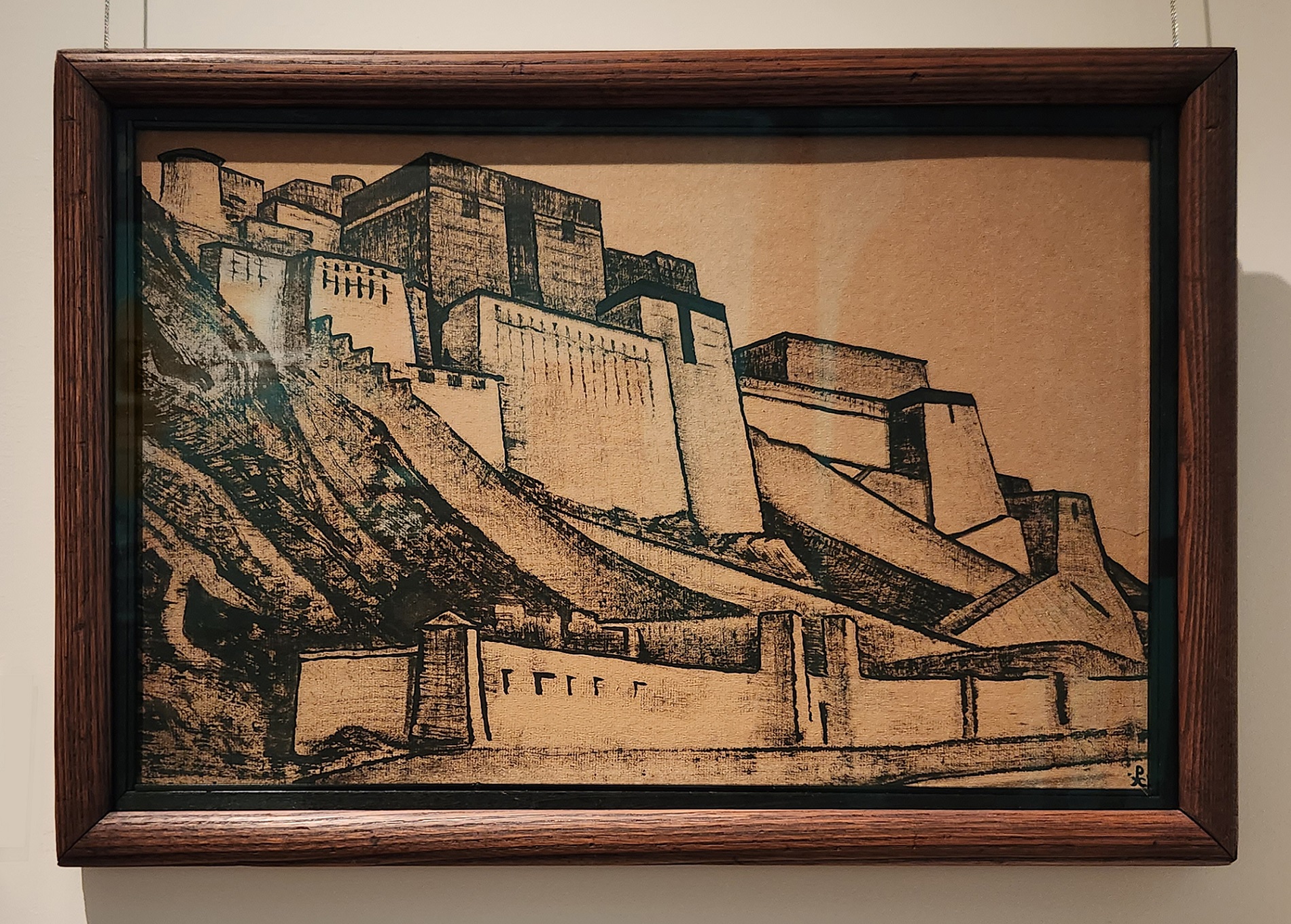

Nicholas Roerich

Untitled

Tempera on canvas laid on board, 12.0 x 15.7 in., 1929

Collection: DAG

|

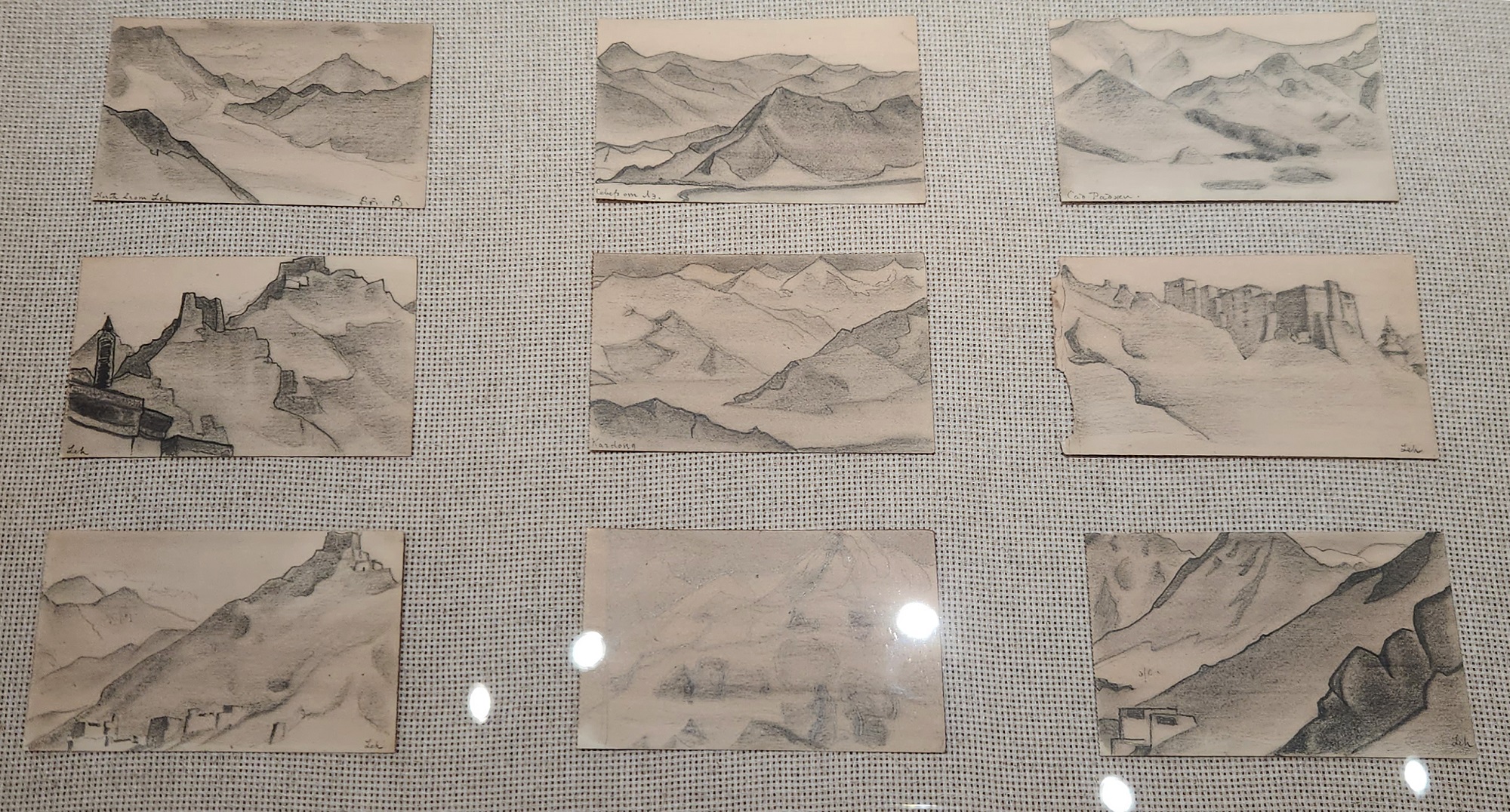

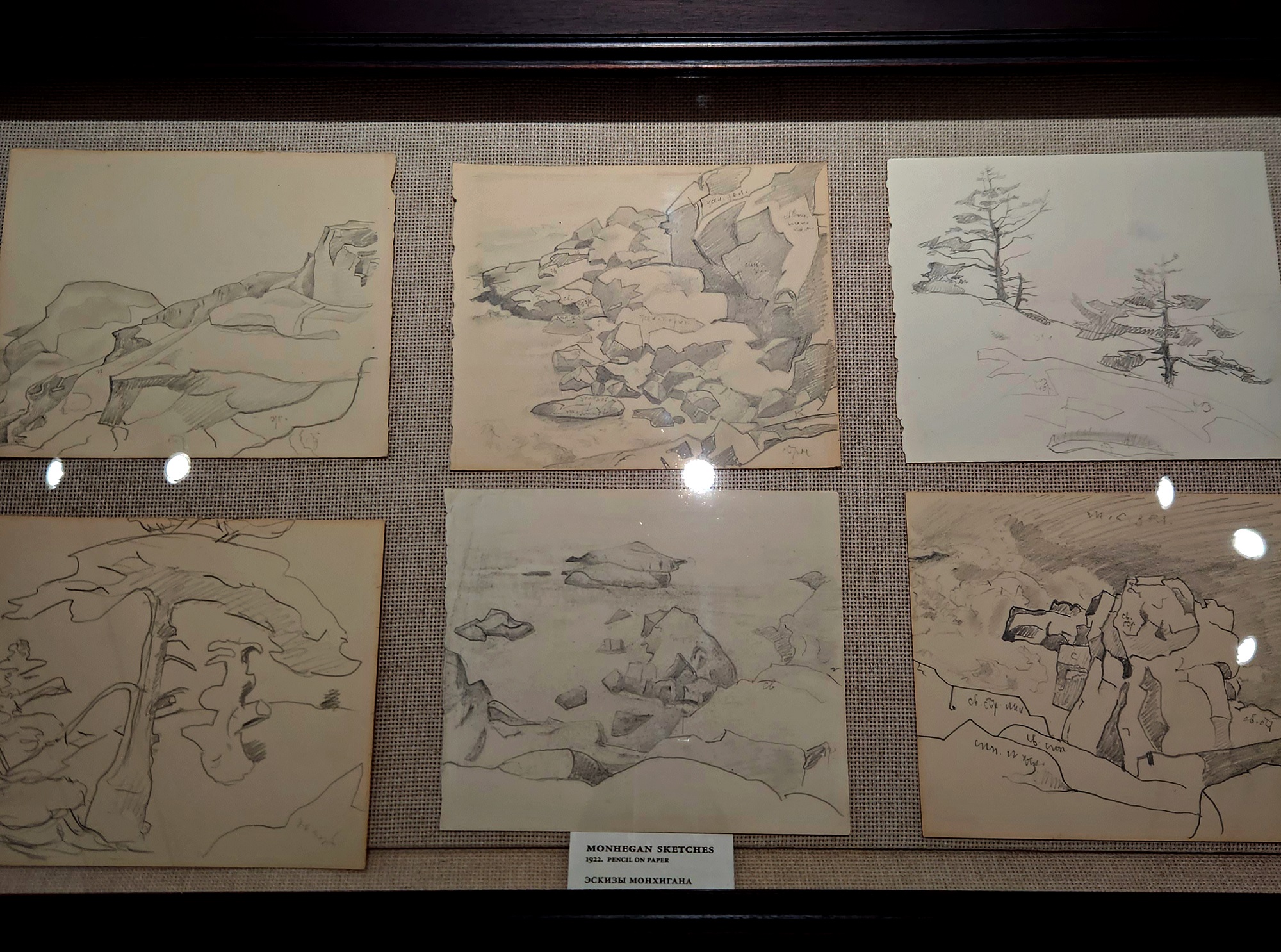

Nicholas Roerich (1874—1947) was a Russian-born artist, philosopher, archaeologist, and author who led a prolific and peripatetic life that was rich with travels, experience and achievement. He created over 6,000 paintings, wrote numerous books, and undertook extensive archaeological expeditions in Russia and Central Asia. Roerich is known first and foremost as an artist, and his paintings explore the mythic origins, natural beauty, and spiritual strivings of humanity and the world, especially those of the Central Asian mountain ranges, including the Himalayas. Nicholas Roerich (1874—1947) was a Russian-born artist, philosopher, archaeologist, and author who led a life that was rich with travels, experience and achievement. He created over six thousand paintings, wrote numerous books, and undertook extensive archaeological expeditions in Russia and Central Asia. Roerich is known first and foremost as an artist, and his paintings explore the mythic origins, natural beauty, and spiritual strivings of humanity and the world, especially those of the Central Asian mountain ranges, including the Himalayas. The Nicholas Roerich Museum in New York City is dedicated to the works of the artist and is located in a brownstone at 319 West 107th Street on Manhattan's Upper West Side. We visited the museum to learn about its collection—read on to find out what we saw there. |

|

|

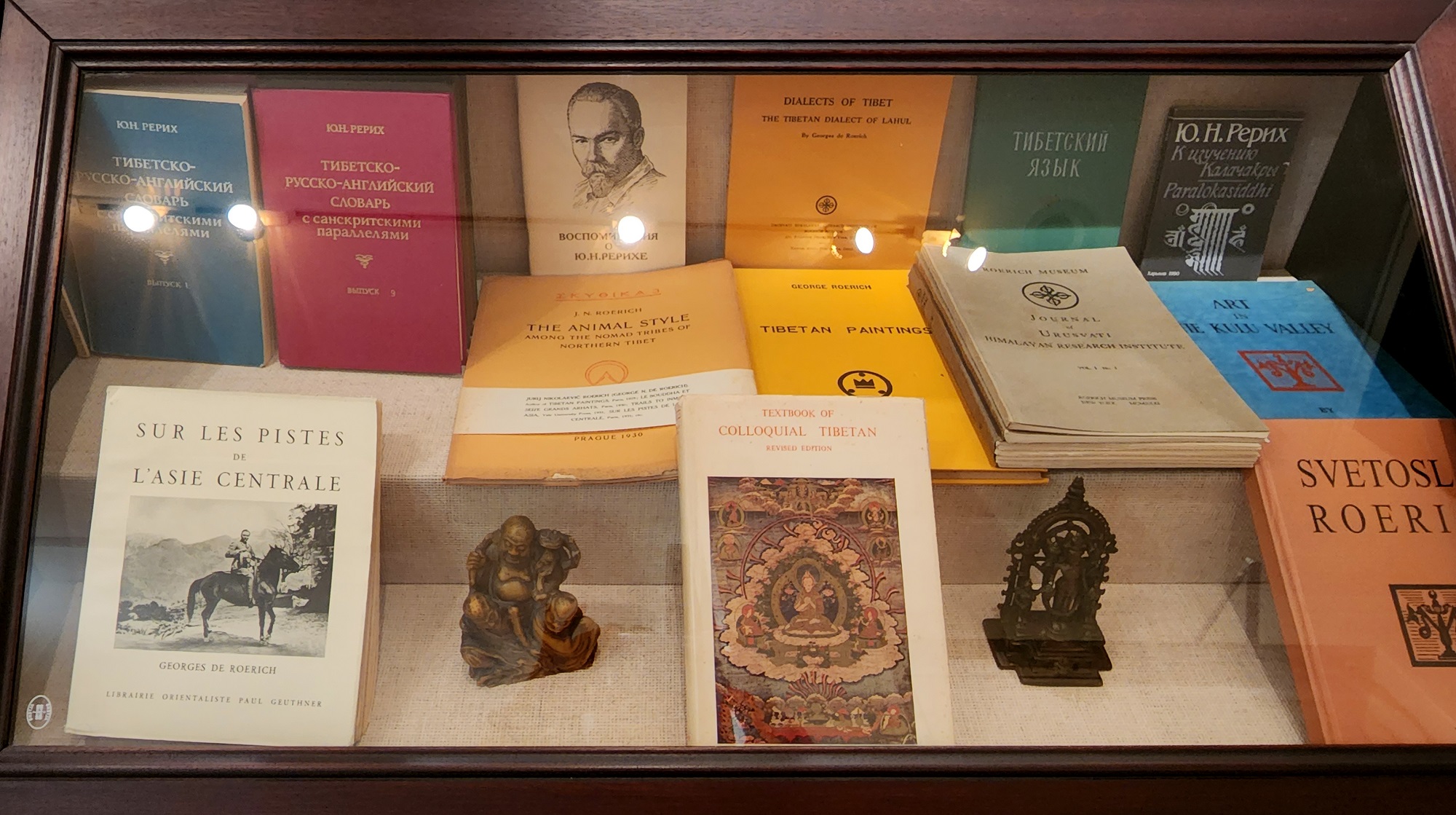

The museum houses approximately two hundred of Roerich's works as well as a collection of archival materials, covering aspects of his artistic practice, science, spirituality, peacemaking, and more. The museum also conducts lectures on art, music, and science, as well as recitals by concert artists and chamber music ensembles. The museum's mission is to make available to the public the full range of Roerich's accomplishments. |

|

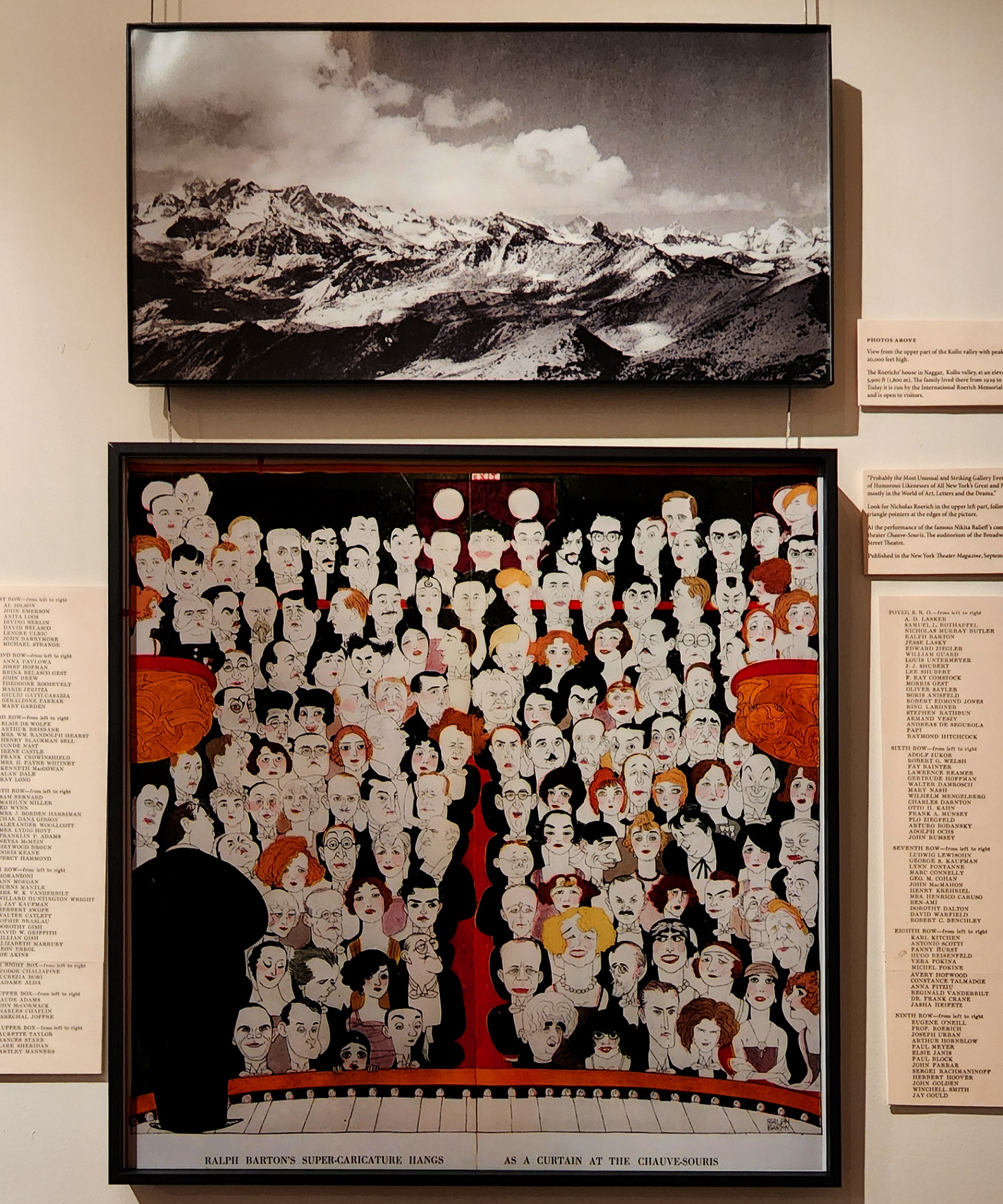

Roerich started out in his youth working with the Russian ballet impresario and founder of Ballets Russes, Sergei Diaghilev. The abstract geometrical shapes he employed to depict mountains was a later development, since he was mostly designing sets for Diaghilev’s operas and painting scenes from Russia’s mythical past at this stage. Following his marriage to Elena (later,’Helena’) Ivanovna Shaposhnikova—the translator of the Theosophical movement’s leader Helena Blavatsky’s book The Secret Doctrine into Russian, he was introduced to the world of Hindu mysticism and the works of writers like Rabindranath Tagore and Aurobindo Ghose. |

|

|

The Altai HimalayaAltai-Himalaya is a travel diary written by Nicholas Roerich during his expedition to India, Tibet, China, Mongolia, and Russia in 1923. The book is a record of his mission, just as his series of paintings Tibetan Paths, Banners of the East, and His Country are records in terms of paint. Roerich wrote the book ‘in the saddle,’ literally and figuratively, as he traveled on horseback through remote and dangerous parts of Asia. The book is a rich and vivid account of his journey, describing the landscapes, people, and cultures he encountered along the way. Roerich's landscapes are manifested in two forms—this travel diary and a set of over five hundred tempera paintings. The book is not just a diary of travel, but a reflection of Roerich's characteristic interests and readings, as well as his artistic and philosophical vision. |

|

In one of his entries for Altai Himalaya, he wrote down a quote by Ghose, indicating to us how he approached the conceptual sublimity posed by mountains and the natural world: ‘Aurobindo Ghose says, “We say to humanity, ‘The time has come when you must take the great step and rise out of a material existence into the higher, deeper and wider life toward which humanity moves. The problems which have troubled mankind can only be solved by conquering the kingdom within; not by harnessing the forces of Nature to the service of comfort and luxury, but by mastering the forces of the intellect and the spirit; by vindicating the freedom of man within as well as without and by conquering, from within, external Nature.”’ |

|

|

The Roerichs left Russia following the Russian Revolution of 1917 and joined the Theosophy Society in London in 1919. According to a scholar, ‘The civil war in Russia had for the Roerichs a millenarian dimension, as would their interest in Tibetan mythology: both believed that the king of Shambhala would eventually return to destroy the wicked and reignite mankind’s creative spirit.’ At the same time he also worked with musical conductors like Sir Thomas Beecham, designing stage sets. Even then, he yearned to go back to the Himalayas, tracing the source of his mystic inspirations. He travelled there eventually with equally capable companions, which included the Indologist Sylvain Levi, starting from Sikkim. Writing about their journey, Ed Douglas writes, ‘Because of the lull in relations between Tibet and British India, news of the Roerichs’ progress on this epic adventure was often patchy; in the summer of 1927 they fell out of contact altogether and remained so for almost a year: they were thought to be dead. In fact, they were merely in prison, detained by the Tibetan authorities despite their passports and passion for Buddhism.’ As soon as they were released in 1928 they headed for India and established the Himalayan Research Institute, ‘or Urusvati, the ‘light of the morning star’, first in Darjeeling and then permanently in the Kullu valley in the far north-west of India.’ |

|

With his stays in colonial India becoming increasingly uncertain, Roerich moved to New York and began a school in Riverside Drive in 1921, called the Master Institute of United Arts, which was financed and directed by Louis Horch. There was a disagreement between the Roerichs and Horch leading to their departure from the building. Roerich had also established a now ominous-sounding Corona Mundi, which tried to preserve cultural treasures imperiled by global conflict and promote artistic exchanges. Even as a New York city resident he spent a lot of his time travelling—especially to India, but also on official missions to places like the Gobi Desert, ‘to look for drought-resistant grasses’. He would die in India, eventually, although his admirers had by then ‘relocated the Nicholas Roerich Museum to a rowhouse at 319 West 107th Street, where Roerich's works are displayed in a museum that few New Yorkers have heard of but that everyone should visit’, according to a journalist’s report in the New York Times. |

|

|

Nicholas Roerich

And we continue fishing

from the series, Sancta

Image courtesy: Wikimedia Commons

Roerich's AmericaRoerich’s residence in and engagement with American life and culture produced a unique encounter where he sought to encourage a revivification of stultifying practices in an age of accelerated industrial capitalism, especially following the First World War. While in Chicago in 1922, he painted a series titled Sancta , drawing from the spiritual teachings of the Reverend Sergius Radonezhsky, for whom he made several pictures. According to a scholar, ‘Roerich painted “Sancta” in order to reveal a spirituality that, while based on one of the greatest icons of Russian culture, was intended to draw attention to those universal spiritual values that, as it seemed to Roerich, had been forgotten by Americans.’ ‘American exhibitions of Roerich’s work were enthusiastically received and caused a sensation’, according to an art historian. ‘Against the backdrop of the Red Scare, which had portrayed Russians as “horrid-looking Bolsheviks with bristling beards,” a completely new and unknown Russia appeared in America with this series. Indeed, no artist had ever managed to convey the entire depth of the Russian soul as effectively as Roerich did in these paintings.’ Serving as soft counter-propaganda to the Russian Revolution, it is also true that Roerich helped rediscover the legacy of American transcendentalists like William Emerson and Henry David Thoreau for a new age of artists and thinkers in America. |

|

‘American exhibitions of Roerich’s work were enthusiastically received and caused a sensation’, according to an art historian. ‘Against the backdrop of the Red Scare, which had portrayed Russians as “horrid-looking Bolsheviks with bristling beards,” a completely new and unknown Russia appeared in America with this series. Indeed, no artist had ever managed to convey the entire depth of the Russian soul as effectively as Roerich did in these paintings.’ Serving as soft counter-propaganda to the Russian Revolution, it is also true that Roerich helped rediscover the legacy of American transcendentalists like William Emerson and Henry David Thoreau for a new age of artists and thinkers in America. Roerich's paintings inspired many American artists, including Georgia O'Keeffe, who was a close friend and collaborator. His ideas about spirituality and mysticism influenced many American writers, such as Jack Kerouac, who was inspired by Altai-Himalaya. His work as an archaeologist and explorer helped to popularize the study of Central Asian culture and history in the United States and his ideas about peace and international cooperation influenced many American activists, including the founders of the United Nations. |

|

Georgia O'Keeffe Lake George Reflection oil on canvas, 58 x 34 in., 1921-22 Image courtesy: Wikimedia Commons |

Roerich himself wrote about the artistic scenario, and its essential link with the nation’s spiritual health, in America in 1923: ‘If I look at America from the red spot of materialistic Wall Street, America naturally is seemingly only materialistic. But my interest has been in the blue and violet rays of your national life. I found them in abundance and they thrilled me. If you consider closely American life, which has nothing in common with the stock exchange or the street, you will be astonished at the revelations. One finds nowhere, for instance, as many creeds and churches next to each other. This is a clear proof of spirituality. When you attend meetings of any denomination you will find crowded halls. The people do not go there for materialistic reasons. They go there for the call of the soul. People are attracted to the teachings of Blavatsky, Vivekananda, Tagore and other great ones. This country gave birth to Emerson and Walt Whitman; they grew up here and found an echo here. These phenomena are naturally hidden from the masses that rush along Broadway and clamor for the mechanical inventions of life. The mechanical side, however, has nothing to do with the spiritual side that thrives in the shadow of elevators and steam shovels… |

|

After identifying American inventors like Thomas Edison as adding to the creative spirit by their sense of industry and innovation, Roerich goes on to write: ‘If you take the poesy of the skyscraper; if you regard the romanticism of the national parks or the profound tragedy and beauty of the Indian pueblos; or again, the somber note of the Spanish relics here, you have so many beautiful things to express that you can understand why the modern American feeling is against repeating the formulas of other countries, but aims to express the original beauties of their own immense land. In this way, to seek original sources, I traveled through America, I visited the beauties of your Middle West plains; through the national parks of New Mexico and Arizona; through Niagara and the Pacific cities. I could perceive what a real future this country has. During the same travels, it is true, I saw many young artists in difficult situations. It is perhaps hard to say this, yet only through Golgothas is achievement tempered. But I could perceive that America had really many souls devoted to art who, living through the hardest experience, do not surrender their living vision. So I feel that, thanks to the artists, America’s creative work is rapidly advancing, and portends to make America a real art center. Not so happy, however, is the state here with art collectors. If I was fortunate in meeting so many prominent artists, I did not have the same fortune meeting collectors. I met throughout the whole country only a few of them. I met several buyers of art, but the real, sincere collectors I met rarely. In several cities I even found that the distinction between buyer and collector was not realized. Similarly, I found a certain attitude, that it was not good taste to have too many art objects in one home. From where comes this unfortunate tale? I do not know, nor am I eager to know, because life itself will erase this foolish prejudice.' |

|

|