Shifting Visions: Teaching Modern Art at the Bombay School

Shifting Visions: Teaching Modern Art at the Bombay School

Shifting Visions: Teaching Modern Art at the Bombay School

|

Shifting Visions: Teaching Modern Art at the Bombay School Sir J. J. School of Art, Architecture and Design Mumbai, 7 March - 20 April 2025 (closed on Sundays and 14 April)

Exhibition by DAG and Sir J.J. School of Art, Architecture and Design M. V. Dhurandhar At Chowpatty Beach Oil on canvas c. 1934 24.0 X 36.0 in. / 61.0 X 91.4 cm. Collection: DAG |

|

|

|

L. N. Taskar Untitled (Maharashtra Temple Scene) Oil on canvas Collection: DAG |

|

EMERGENCE

|

|

Pestonji Bomanji Untitled Oil on Canvas, c. 1900 Registered work (non-exportable)

|

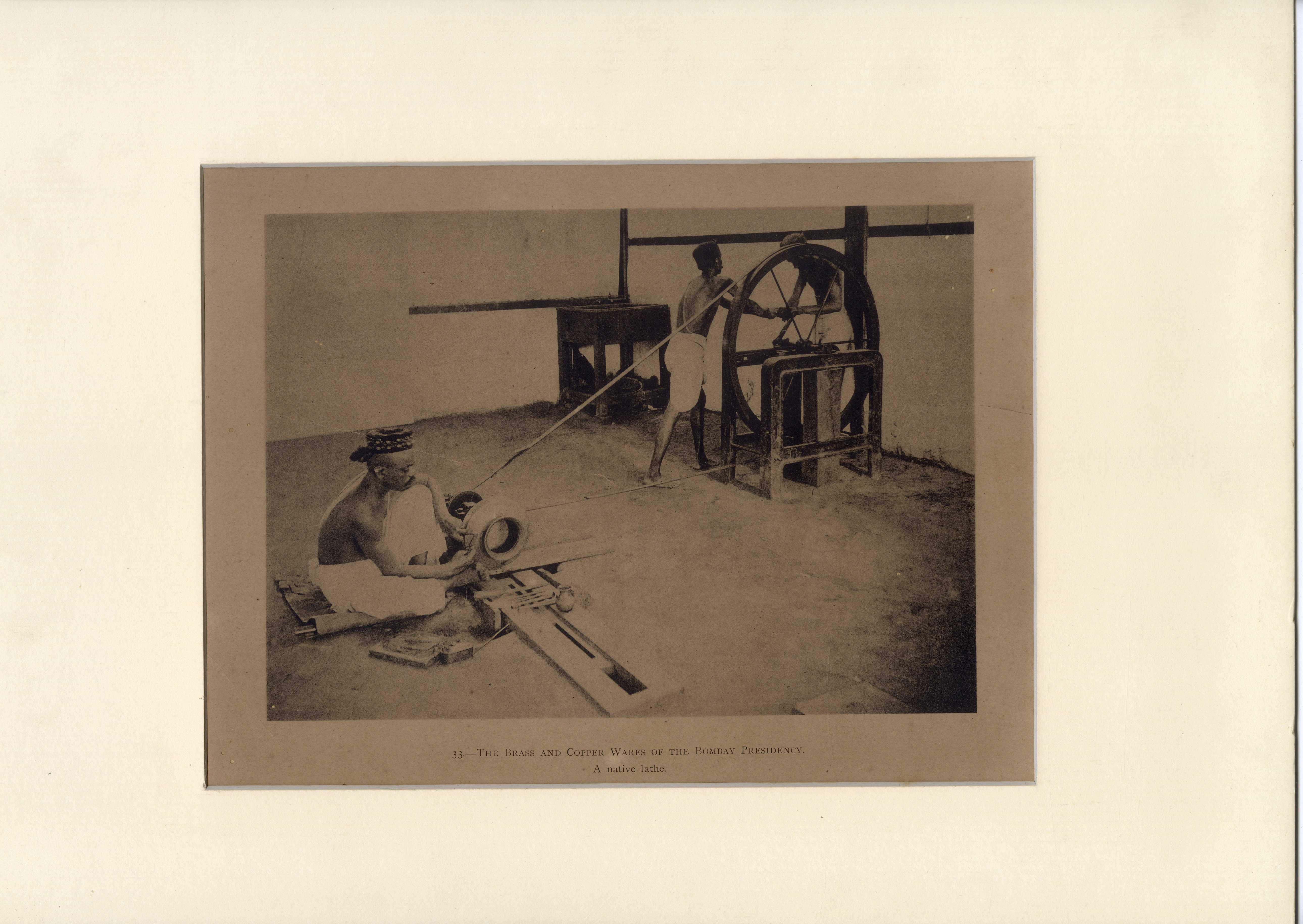

M. V. Dhurandhar

The Brass and Copper Wares of the Bombay Presidency (Lamps)

Lithograph on paper pasted on paper, 1896-97

Collection: DAG

|

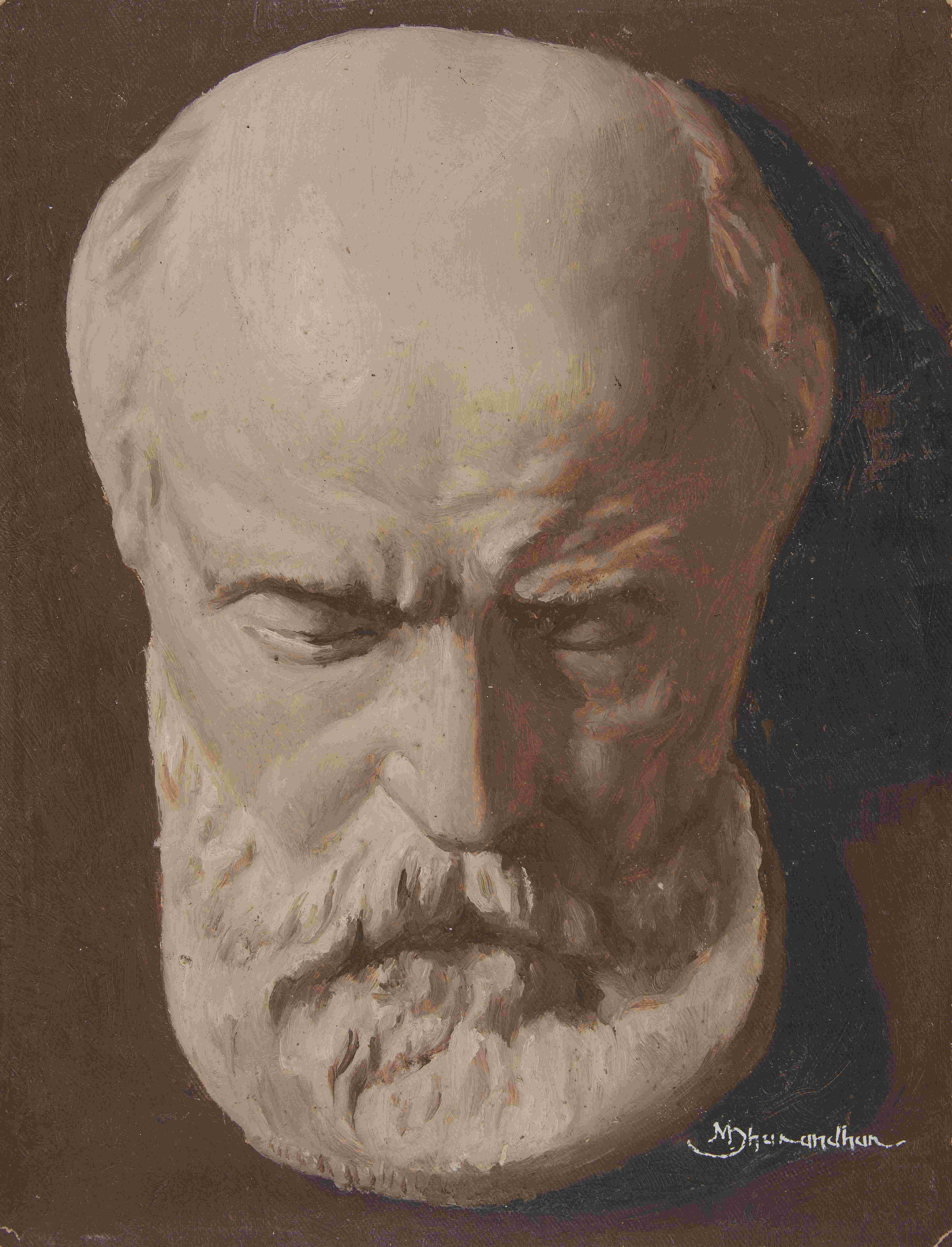

M. V. Dhurandhar

Untitled

Oil on Paper

13.0 X 9.5 in. / 33.0 X 24.1 cm,

Collection: DAG

|

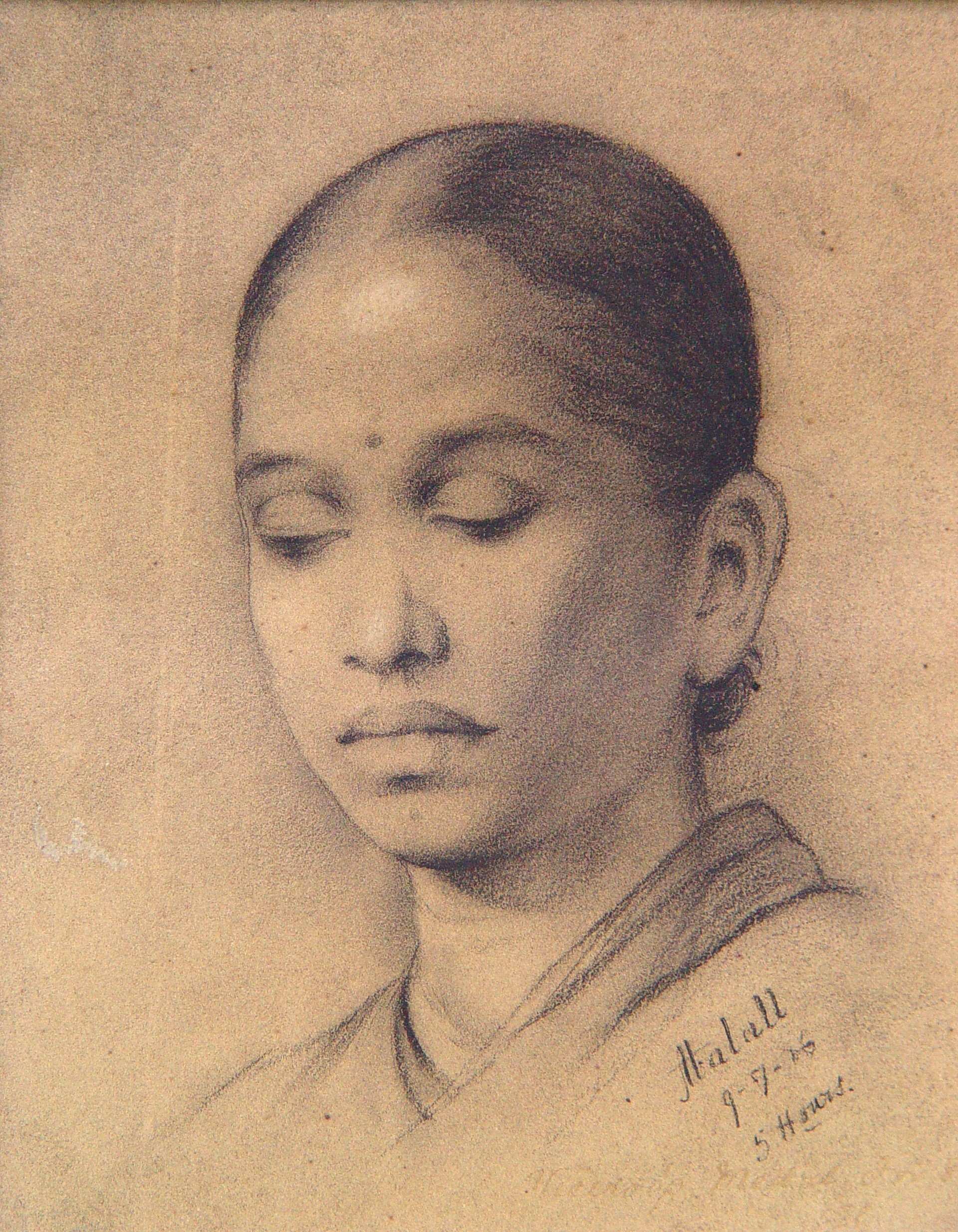

Abalal Rahiman

Untitled

Charcoal dust on paper

17.5 X 14.0 in. / 44.45 X 35.56 cm,

Collection: Sir J. J. School of Art

|

|

CLASSROOM TO COMMISSIONS

|

|

M. K. Parandekar Untitled (Karla Caves) Oil on Canvas Collection: DAG |

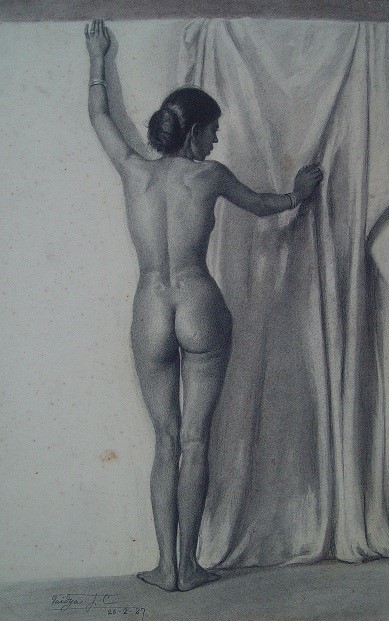

M. V. Athavale

Untitled

Pencil on Paper

27.5 x 19.5 in./69.85 x 49.53 cm

Collection: Sir J. J. School of Art

|

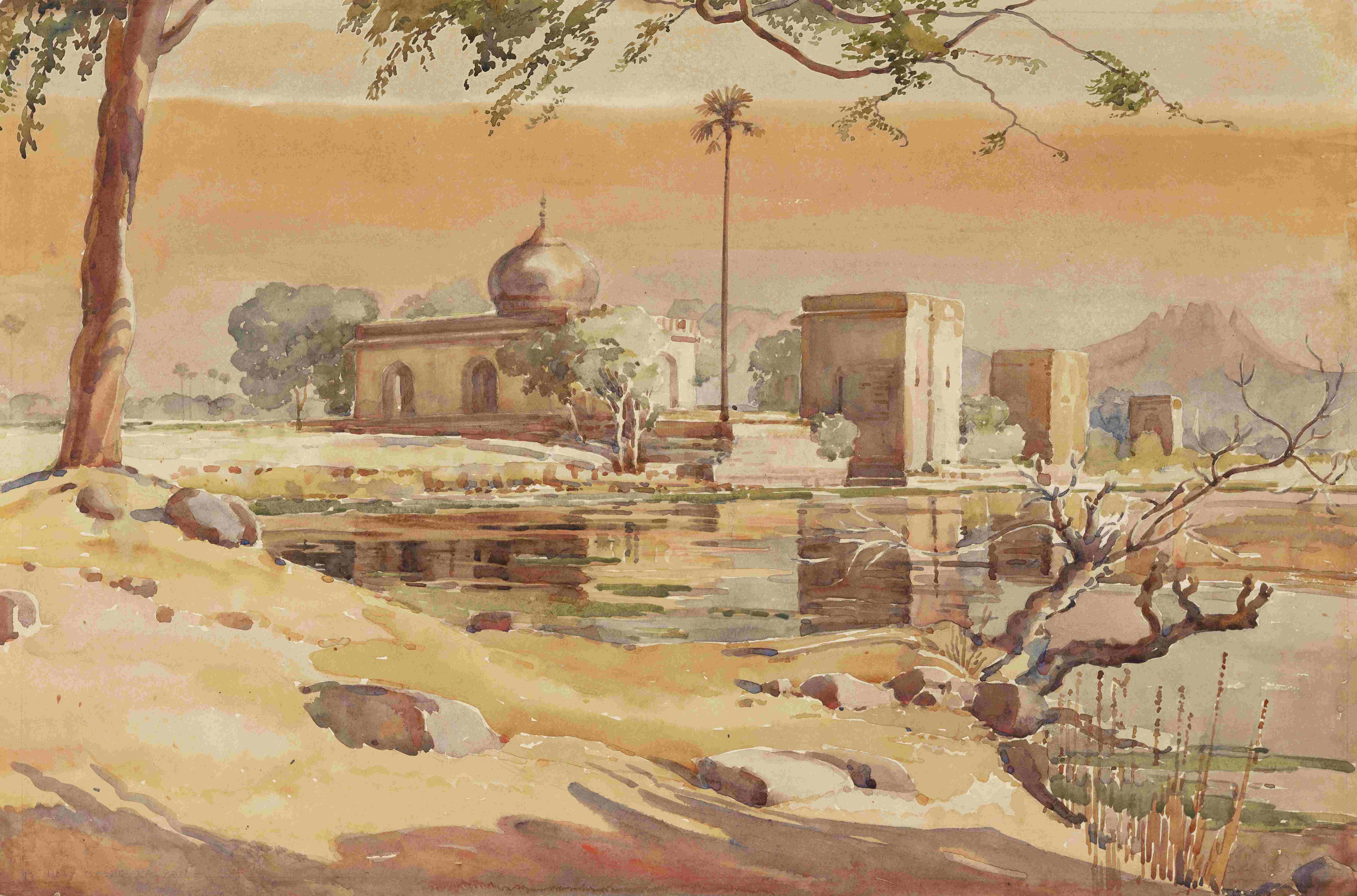

N. R. Sardesai

Jogeshwari Caves

Watercolour on paper, 1940

9.2 X 13.2 in. / 23.4 X 33.5 cm.

Collection: DAG

|

D. G. Karanjgaonkar and R. D. Dhopeshwarkar

Untitled

Watercolour on paper, c. 1926

18.11 X 14.13 in. / 46.02 X 35.91 cm

Collection: Sir J. J. School of Art

|

|

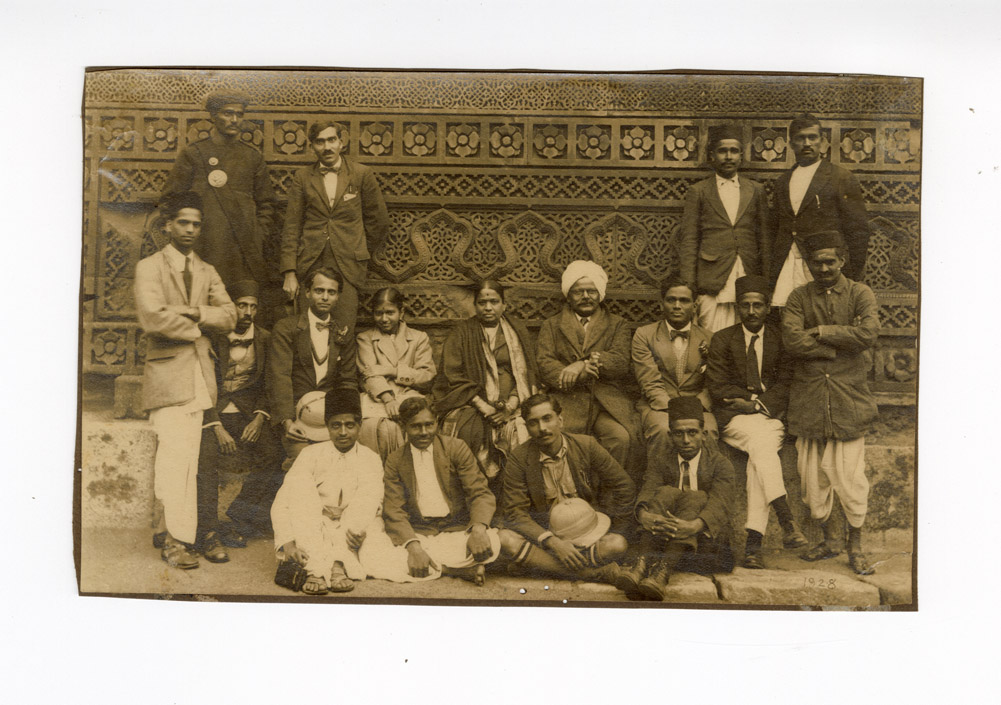

THE SOCIAL LIFE OF THE SCHOOL The history of the J. J. School today is often periodised by the tenure of its various British Principals, or landmark events like the establishment of different departments. A closer look into the world of artists like M.V. Dhurandhar, who took his role as an educator and artist in the public eye seriously, reveals his practice of ‘decades of careful self archiving’, and allows us to see the larger social world within which they lived.

|

|

M. V. Dhurandhar Bal Gandharva Oil on canvas pasted on board, 1941 Collection: DAG |

Unidentified photographer

An institutional Photograph on the occasion of Dhurandhar officiating as the Director of J. J. School

Pestonji Bomanji

Self-Potrait

Unidentified photographer

M. V. Dhurandhar, Ambika Dhurandhar and Gangubai with students of J. J. School of Art during a study tour

|

EXPERIMENTS IN MODERNISM

For the modern to emerge, a historical accounting of past traditions was required. It provided an important stage, when Indian aesthetic traditions were approached—and eventually ‘revived’—through the rigour of an academic, reconstructed eye. Gladstone Solomon, Director of the Sir J. J. School from 1918 onwards, wrote: ‘Revivalism in art is not merely an act of nostalgia; it is a complex interplay of cultural identity and historical consciousness...’ Led by figures such as G. H. Nagarkar and J. M. Ahivasi the final decades of colonial rule saw a gathering of cultural forces that heralded the arrival of an ‘Indian’ style in western India.

|

|

Charles R. Gerrard The Garden of the Director's Residence, the Sir J. J. School of Art, Bombay Oil on Masonite board Collection: DAG |

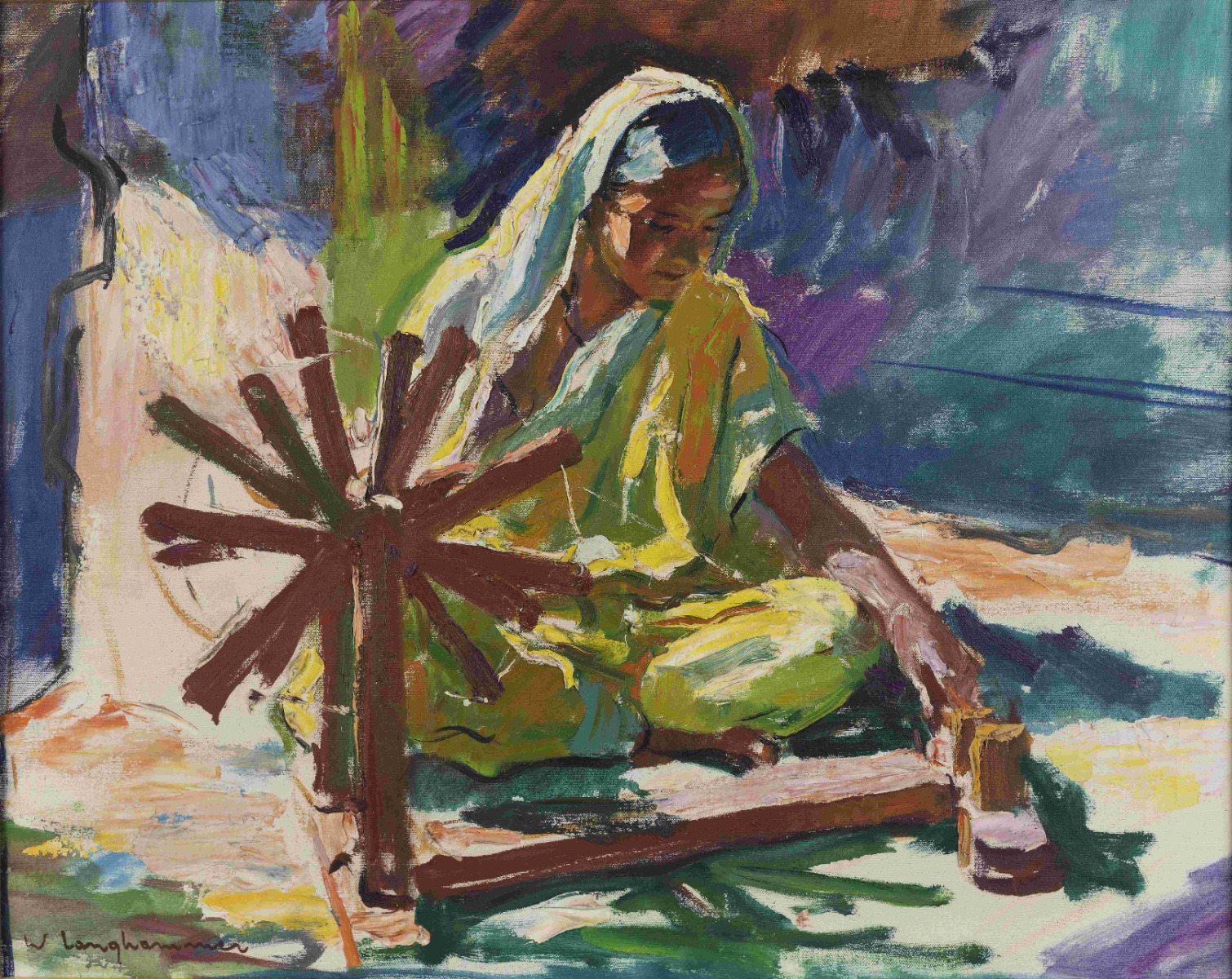

Walter Langhammer

Portrait of a Woman at a Spinning Wheel

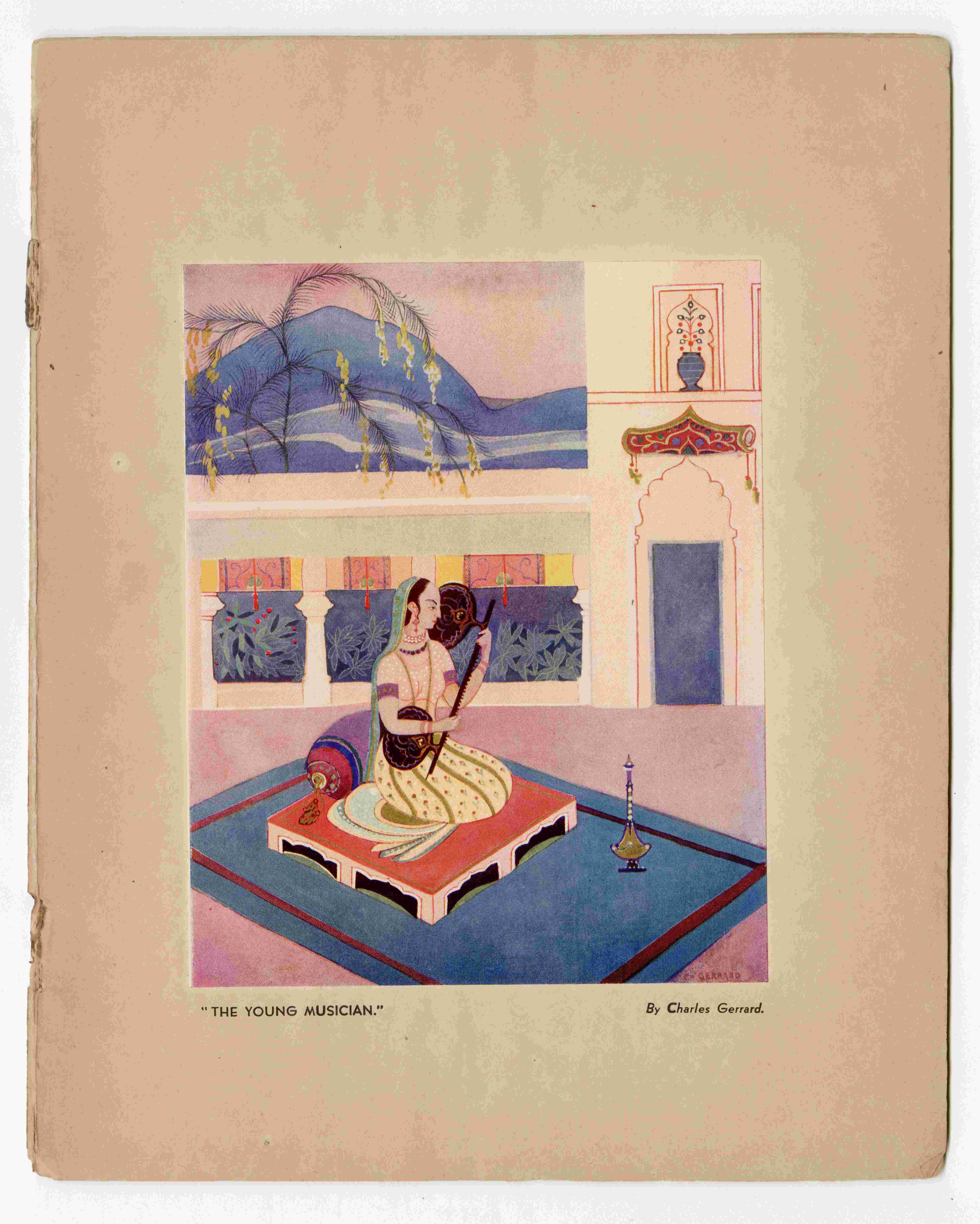

Charles Gerrard

The Young Musician

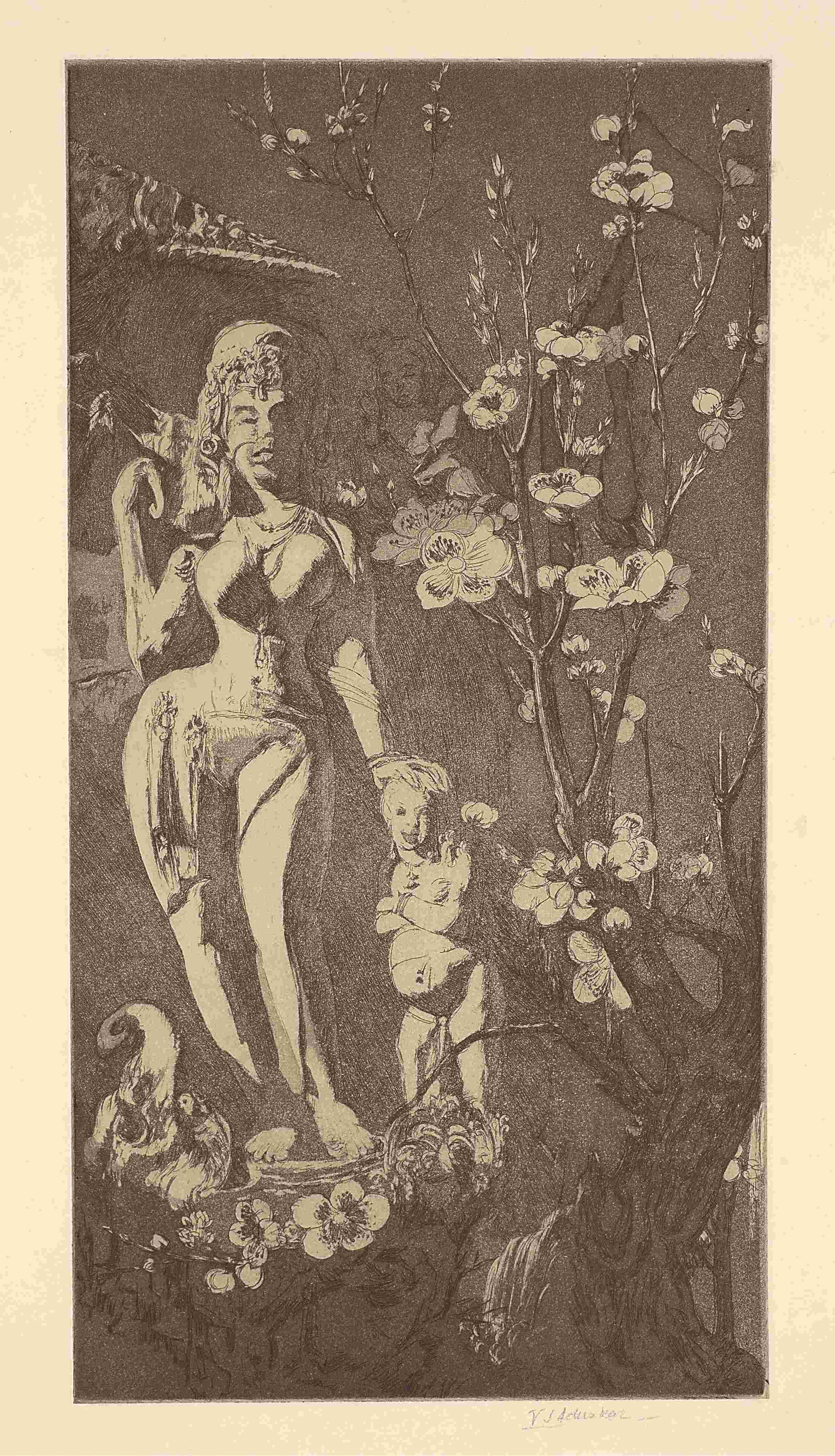

V. S. Adurkar

Untitled

|

Credits:

|

Presented by