Scripting the Camera: Satyajit Ray’s cinema as ‘archive’

Scripting the Camera: Satyajit Ray’s cinema as ‘archive’

Scripting the Camera: Satyajit Ray’s cinema as ‘archive’

collection stories

|

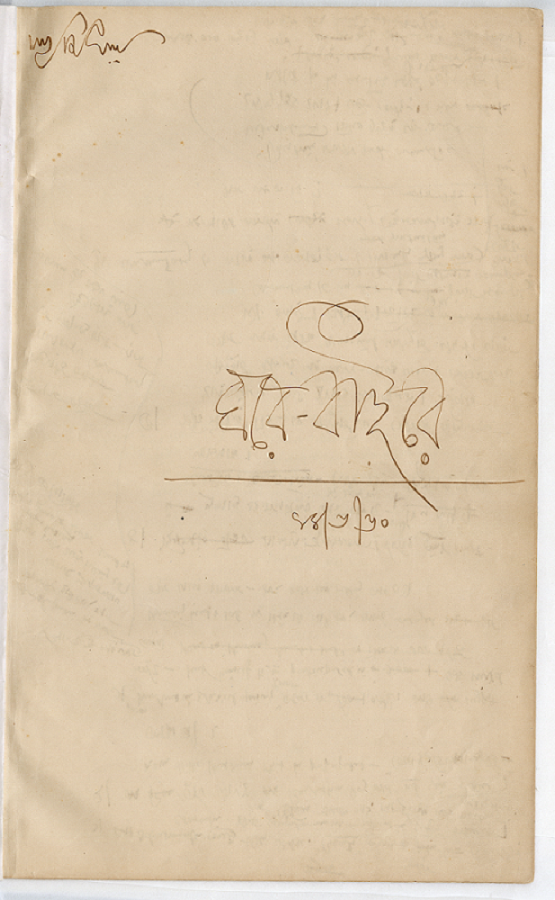

The DAG Archive has over 90,000 photographs taken by Nemai Ghosh, a bulk of which includes still photographs and behind the scenes images of films as well as candid and staged portraits of Satyajit Ray. In conjunction to these materials, DAG Archive has also acquired a set of two notebooks of Ray which contains the hand-written film scripts of Ghare Baire (The Home and The World, 1984) and Samapti (The Conclusion) which is one of the short films from the anthology, Teen Kanya (Three Women, 1961). Interestingly, both these films are adaptations from Rabindranath Tagore’s literary works. ‘The script sees the presentation of every event and character as a problem which it solves by finding a way to make it fresh, unique, free of conventions.’ —Chidananda Dasgupta, The Cinema of Satyajit Ray |

|

Satyajit Ray directs a scene from behind the camera, 1977 Inkjet print on archival paper, 2012 (printed by DAG) |

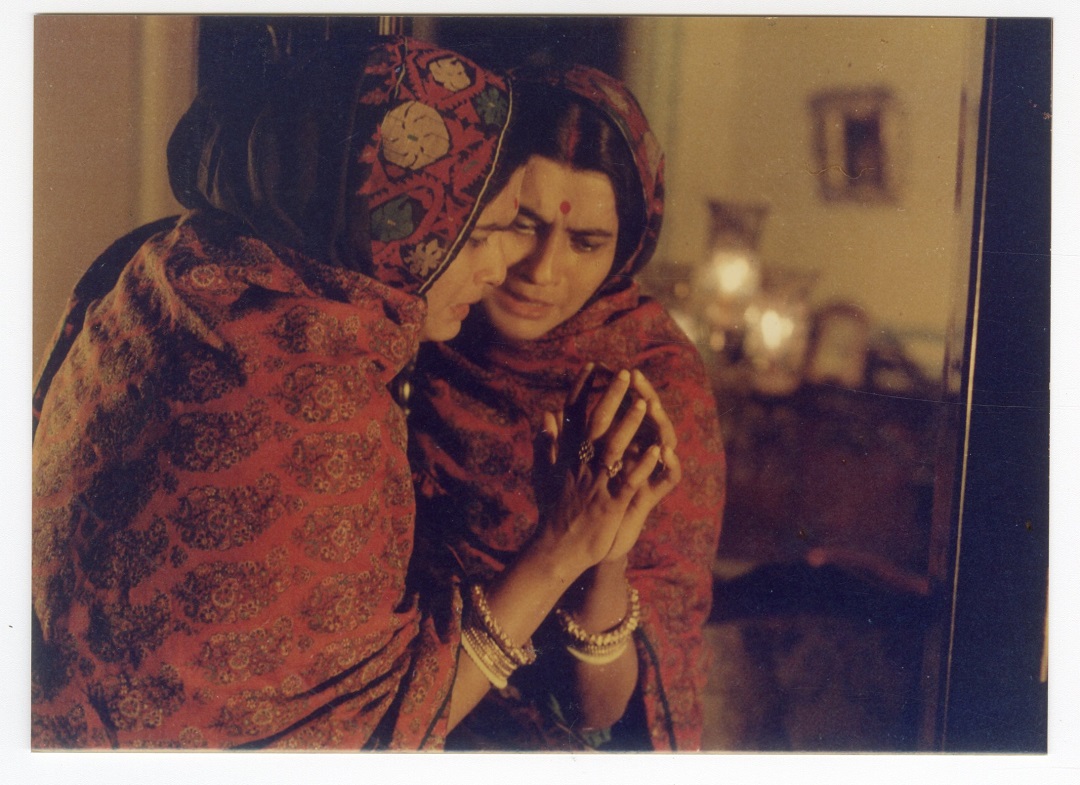

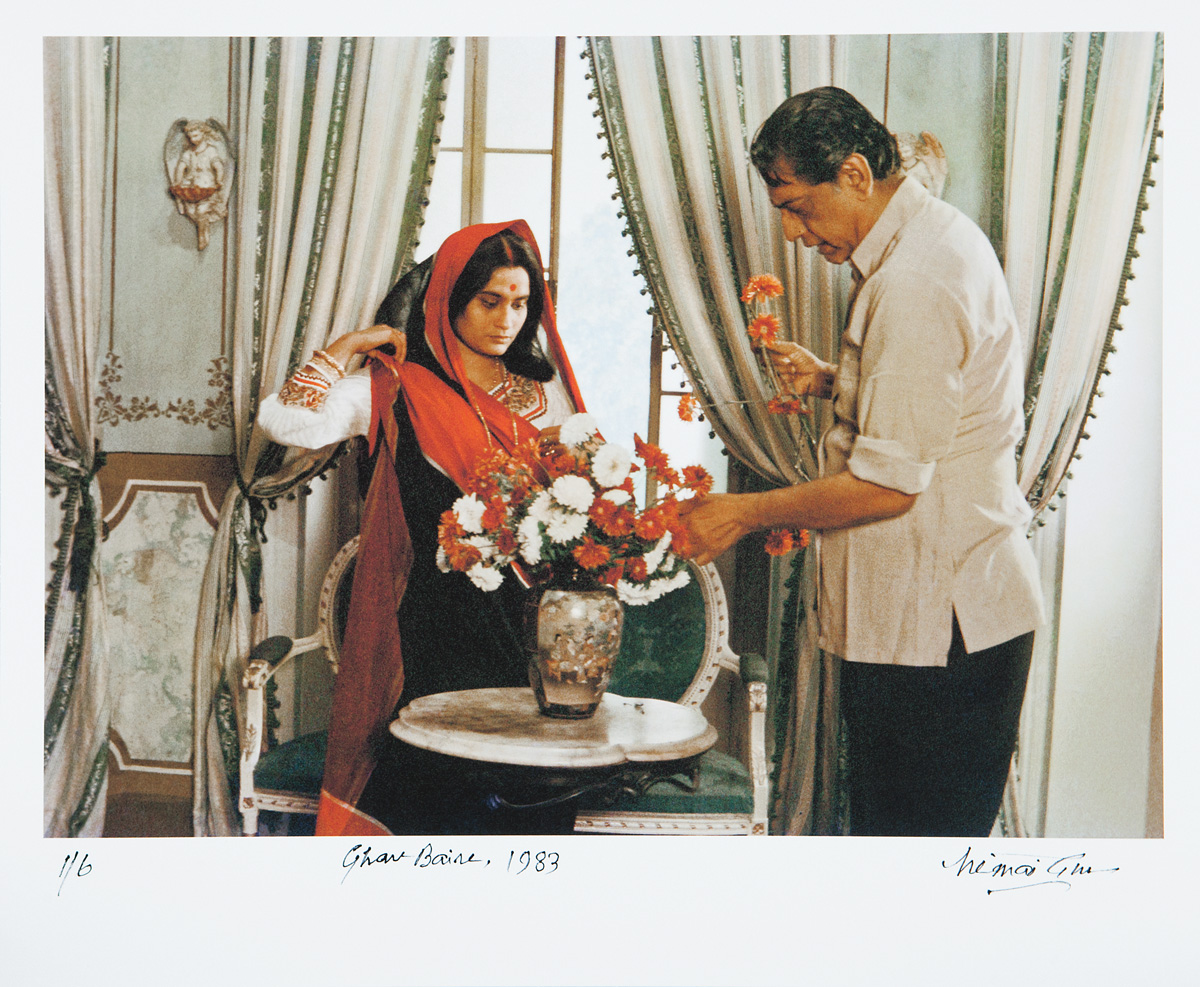

STILL FROM GHARE BAIRE (THE HOME AND THE WORLD)

Inkjet print on archival paper, 2012 (printed by DAG)

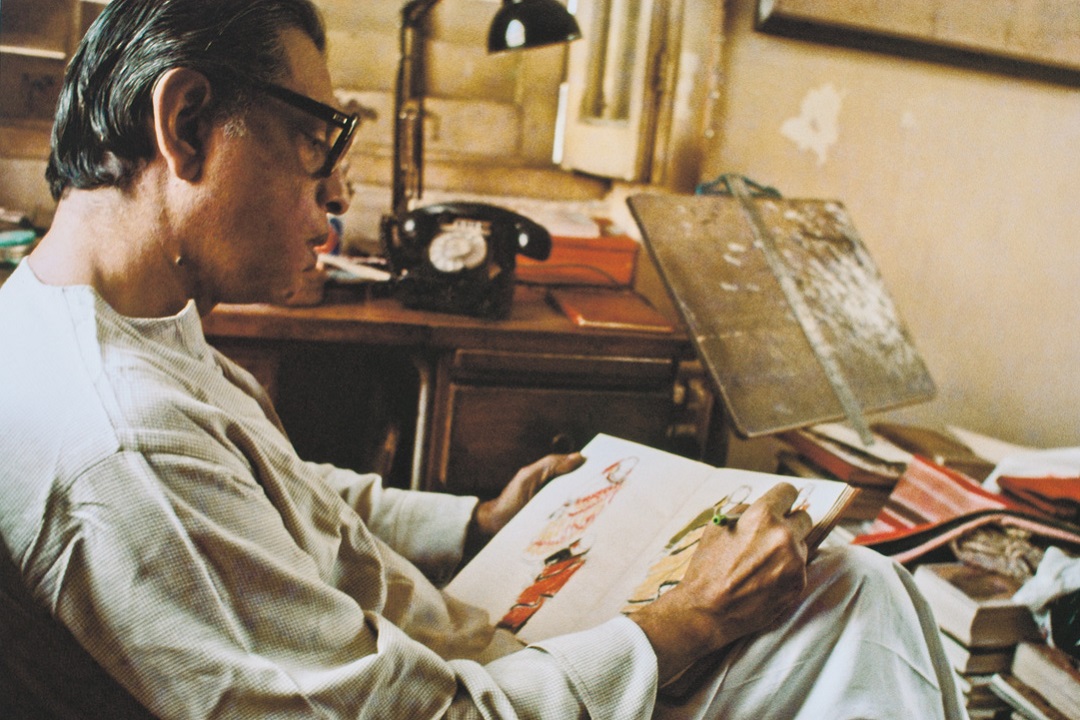

Acts of Reading and Visualising a FilmIn 1960, Satyajit Ray penned down the first draft of the script of Ghare Baire. But the story of this adaptation goes more than a decade back to 1948, when Harisadhan Dasgupta was originally meant to direct the film. Owing to ideological differences and conflicts the film got shelved. It was in 1984 that the film was finally released. But narrating this story does not merely serve as an anecdote; instead, it throws light on the fundamental link between a film script and the filmmaker’s vision. Furthermore, it makes us ask: what is the significance of a film script in an archival collection? |

|

Photograph of a set design sketched by Ray for Ghare Baire Inkjet print on archival paper, 2012 (printed by DAG) |

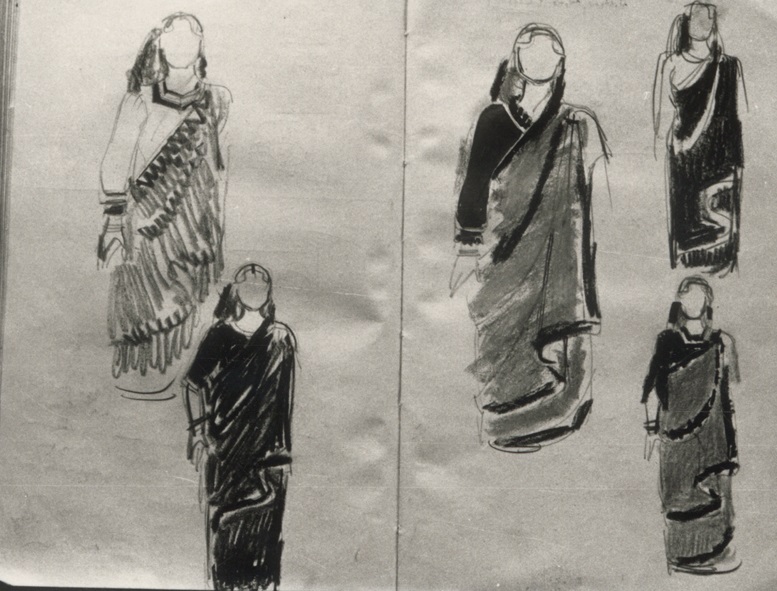

Photograph of Costume Design Sketches for Bimala, Ghare Baire

Inkjet print on archival paper, 2012 (printed by DAG)

Looking at each stage of this process: from its birth in the form of a script, to executing its screenplay and storyboard, to eventually reading the still photographs of production (by Nemai Ghosh), allows for a greater understanding of Ray’s film-making methods. For Ghare Baire, when Ray began writing the script in 1960, he initially thought of casting Soumitra Chatterjee as Nikhilesh and Madhabi Mukherjee as Bimala. But, eventually, the casting changed by the time the film got made. Along with costume design sketches, he also made sketches of set designs during the script-writing stage. This highlights Ray’s involvement in each aspect of the film-making process. |

|

Still from the trilogy, Teen Kanya (from the film, Samapti) Inkjet Print on Archival Paper, 2012 (Printed by DAG) |

Still from the film, Samapti (trilogy, Teen Kanya)

Inkjet print on archival paper, 2012 (printed by DAG)

|

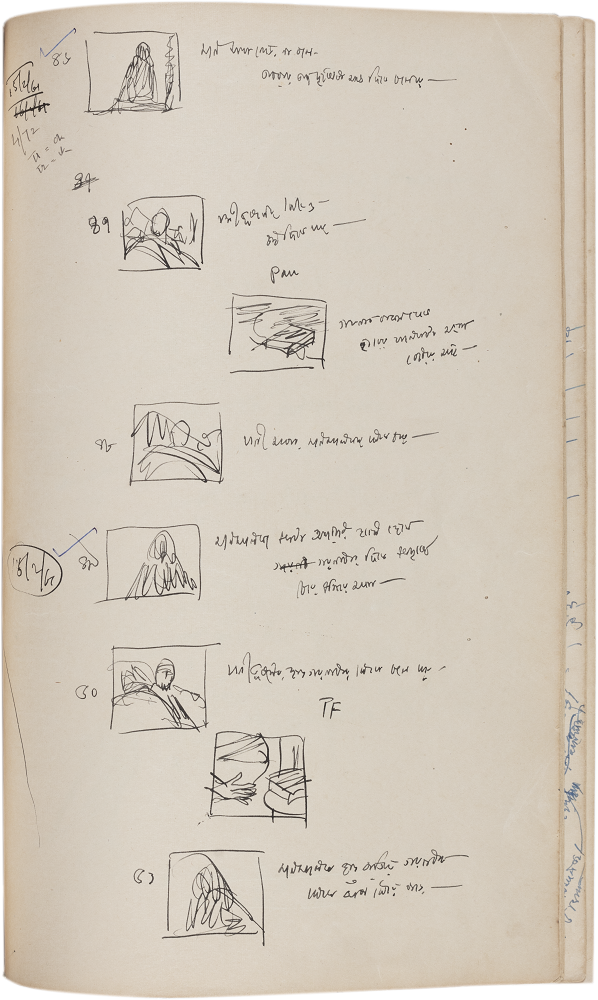

Similarly, the script of the film, Samapti (the concluding part of the three-film anthology, Teen Kanya) is divided into eight sequences in the notebooks. Juxtaposing each sequence with the film scenes, enables the viewer to better contextualise the role of cinematography and editing in Ray’s cinema. |

|

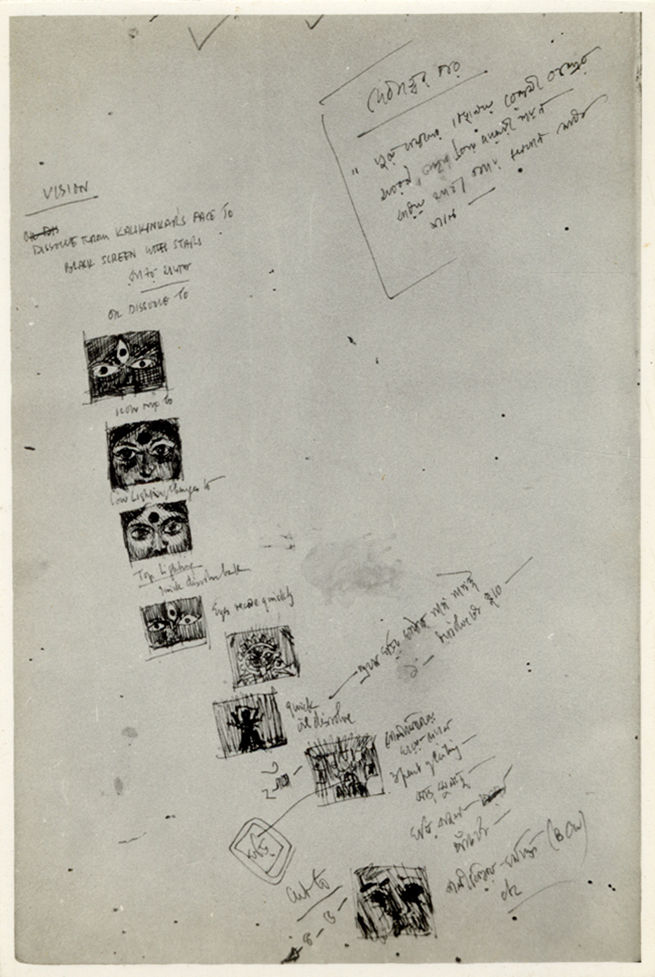

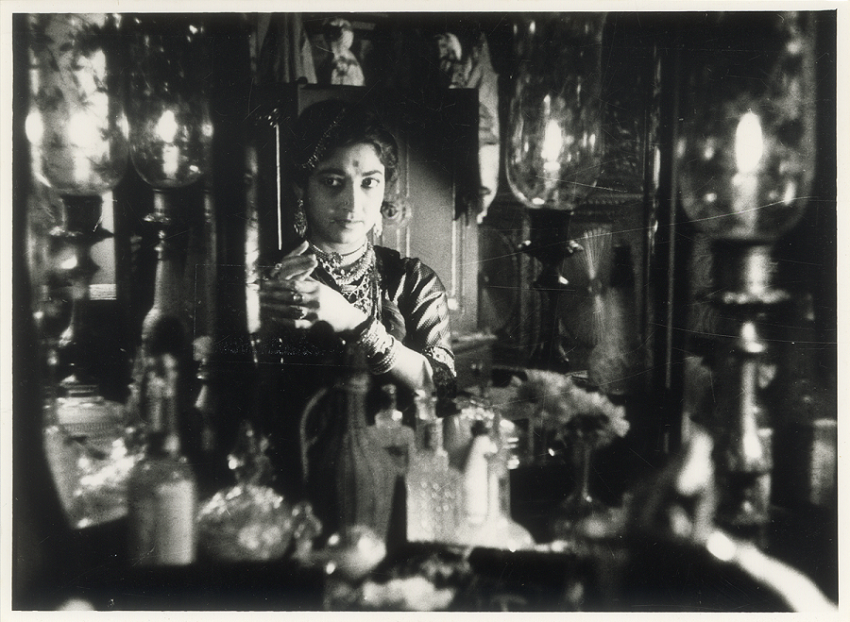

The DAG Archive also contains scanned photographs of sections from his other notebooks, such as the one pertaining to Ray’s classic film, Devi (The Goddess, 1960), which contains sketches of a scene, where Kalikinkar Chaudhuri (played by Chhabi Biswas) has a dream where he is visited by a deity, convincing him that his daughter-in-law is the reincarnation of the Goddess Kali. In the scene, the faces of the Goddess and Dayamoyee are superimposed on each other, becoming one and the same. |

|

Still from Devi (The Goddess)

Inkjet print on archival paper, 2012 (printed by DAG) |

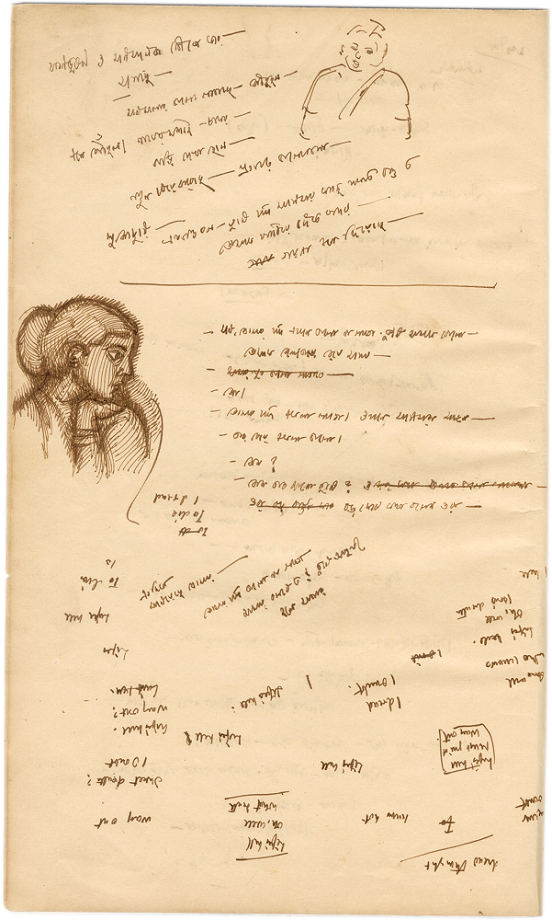

A page from Ray’s notebook, featuring a rough sketch of a woman, along with musings and dialogues and scenes from the film, Monihara (from Teen Kanya)

Ink on paper

A page from Ray’s notebook, featuring sequence break for the film, Monihara (from Teen Kanya)

Ink on paper

Still from the film, Monihara (trilogy, Teen Kanya)

Inkjet print on archival paper, 2012 (printed by DAG)

Ray's Script-writing styleMainstream film script-writing developed in India in the 1930s with the coming of the studio era. The format of a film script generally included the screenplay, dialogues and shot transitions. But Ray did not adhere to the fixed idiom of script-writing and devised a painstaking process that included individual frames sketched-out, with musical notations as well as camera movements and transitions between sequences and shots extensively detailed on the page before the shoot. The act of reading Ray’s film scripts are fascinating owing to its personalised format, that often included scribbles, sketches, doodles, music notations on the margins of the pages, that highlight Ray’s artistic process further. |

|

Satyajit Ray narrating the script to Swatilekha Sengupta on the set of Ghare Baire Inkjet print on archival paper (Printed by DAG, 2012) |

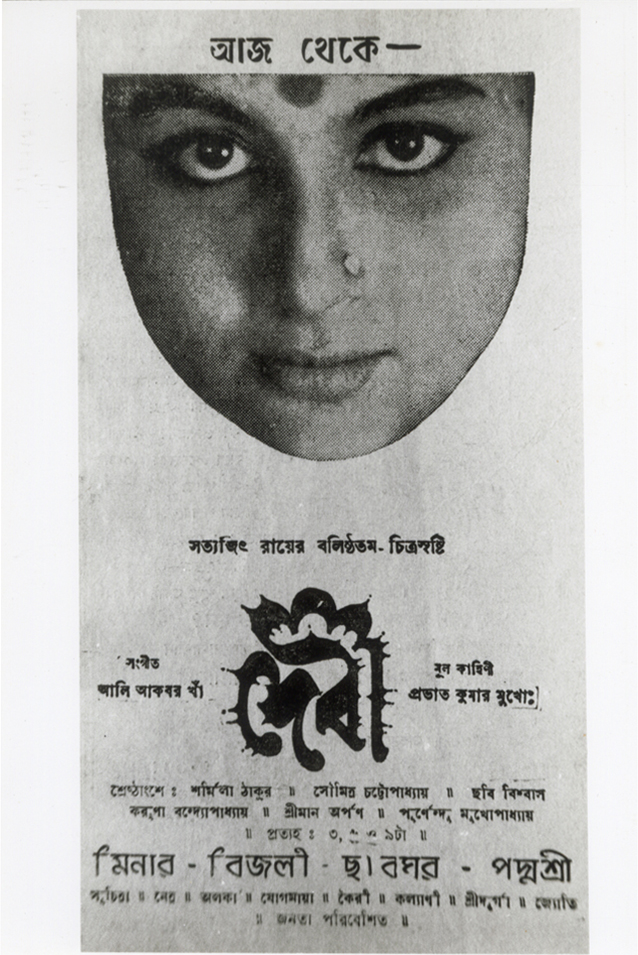

Movie poster of the film, Devi (The Goddess)

Inkjet print on archival paper, 2012 (printed by DAG)

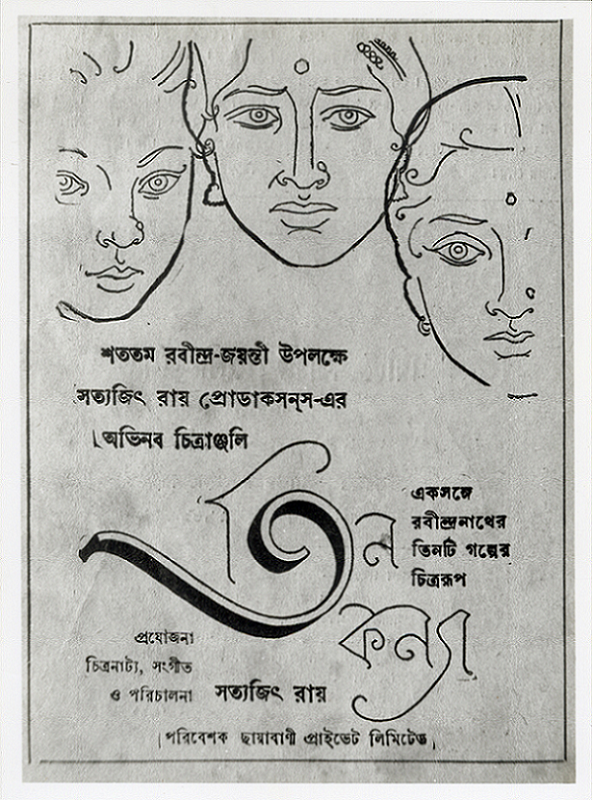

Poster for the film, Teen Kanya (Three Women, 1961)

Nemai Ghosh, digital print on paper, 1961

Scanned photograph of the movie poster. Printed by DAG, 2012

Adaptation as 'cinema'Adapting a literary work into cinema further complicates the question of how we understand film as a visual medium. For instance, though Ghare Baire is considered as one of the earliest conceived film scripts of Ray, it was met with criticism when it was released in 1984. But that does not diminish the historical relevance of the film; instead, it highlights how the ideological interpretation of characters or events in a novel may differ for an author and their readers, as opposed to a film director. Ghare Baire was also made in the last phase of his career, when he began showing signs of steady deterioration in his health. Large sections of the movie was supervised by his son, Sandip Ray, under the directorial ambit of his father. Unlike his earlier adaptations, such as Devi (The Goddess, 1960) and Teen Kanya (Three Women, 1961), amongst others, the all-round mastery that is synonymous with Ray’s oeuvre is absent in his later works, according to some critics as well as his close friend, Chidananda Dasgupta. |

|

The Shift in Ray’s Aesthetics |

|

Still From Devi (The Goddess) Inkjet print on archival paper, 2012 (printed by DAG) |

Satyajit Ray and Swatilekha Sengupta on the sets of Ghare Baire (The Home and the World)

Inkjet print on archival paper, 2012 (printed by DAG)

The cinematic aesthetic of a film finally rests on the nature of the collaboration between the director and the cinematographer. Satyajit Ray and Subrata Mitra were one such remarkable duo, collaborating on some of the greatest films in history, including Pather Panchali, Jalsaghar, Devi, Mahanagar, Charulata, and Nayak, made between the 1950s and the 1960s. However, owing to the rift between Ray and Mitra, due to ‘Ray’s single-minded vision of film-making’ (as written by Robinson), they eventually parted ways. It was then that cinematographer Soumendu Roy began working with Ray on his subsequent films. And from this period onwards a shift can be observed in Ray’s visual imagery as well. With the emergence of colour films in Bengali cinema, the aesthetics changed further. In 1962, Satyajit Ray made his first colour film, Kanchenjungha, which allowed him to capture the scenic beauty of the landscape around Darjeeling in the north of West Bengal. But from 1980s onwards, the texture and colour saturation changed further in Ray’s colour films. These transitions also foreground the technological developments taking place in the regional cinemas of India at the time. |

|

The Cinematic Duo: Nemai Ghosh and Satyajit Ray |

|

Satyajit Ray and cinematographer Soumendu Roy during the shoot of Ashani Sanket (Distant Thunder, 1973) Inkjet print on archival paper, 2012 (printed by DAG) |

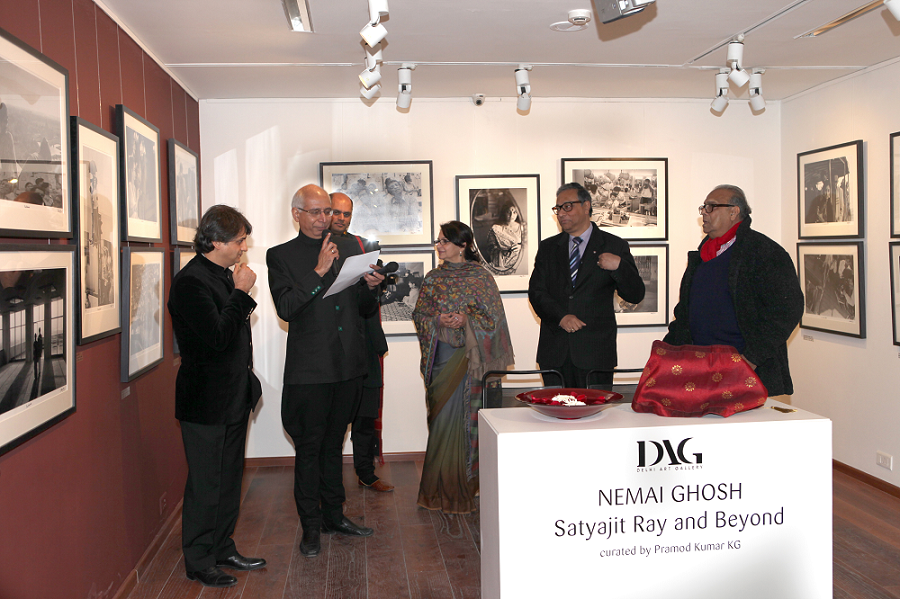

Archival photograph of DAG exhibition, ‘Nemai Ghosh: Satyajit Ray and Beyond’, 2013

Archival photograph of DAG exhibition, ‘Nemai Ghosh: Satyajit Ray and Beyond’, 2013

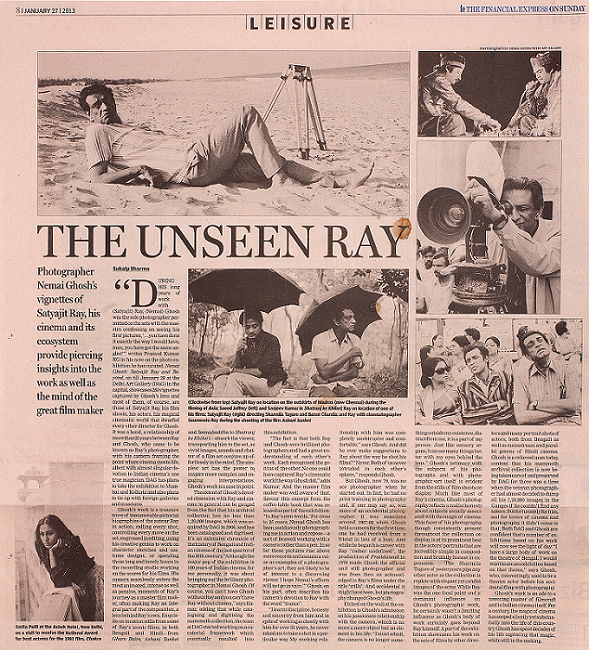

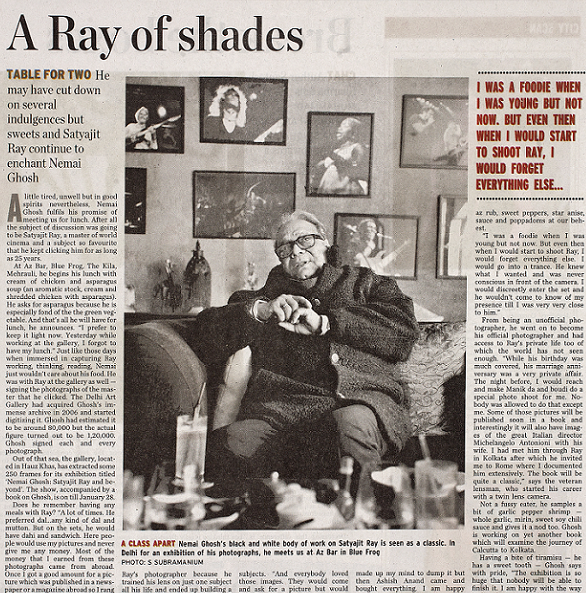

Review, The Financial Express (authored by Sukalp Sharma), 2013

Review, The Hindu (authored by Shailaja Tripathi), 2013

What Nemai Ghosh’s still photography achieves is that it freezes Ray’s moving images in time. It enables the image to become ‘iconic’ and ultimately becomes the mediator between the personal and the public. These photographs become ancillary tools to disseminate the image of Ray that establishes him as a 'persona'. The collaboration between Ghosh and Ray serves as documentation, as testimony, as practice and as archive. It was the personal collection of Nemai Ghosh, which contained the negatives of photographs, that made it possible for DAG to launch an exhibition on the photographic archive in 2013, ‘Nemai Ghosh: Satyajit Ray and Beyond’ curated by Pramod Kumar KG (which was also published as a book). This collection further enriches the field of cinema studies, in terms of expanding the scope of Ray’s film-making process.

|

|

Behind the ‘Persona’ The documentary sensibility of Ghosh’s photography allows us to look at the filmmaker, in moments of vulnerability, good humour, and thoughtfulness, adding texture to the personality of the filmmaker as it bleeds into the making of his film. The archive also has a number of ‘Behind the Scenes’ photographs taken by Nemai Ghosh which ultimately succeed in looking at Ray beyond the ‘aura’ that surrounds him and his authorship. These photographs of his interaction with his actors or his crew members throw new light on many aspects of the production process. They allow us to appreciate the complex social interactions that also underpin his filmmaking, influencing narration, scene development, camera angles, and production work. |

|

Ray behind the camera with crew and assistant director Suhashini Mulay during the shoot of Jana Aranya (The Middleman, 1975) Inkjet print on archival paper, 2012 (printed by DAG) Museum Story credits: written by Brishti Modak |