Translating the Modern: A Walk Around Santiniketan, Part I

Translating the Modern: A Walk Around Santiniketan, Part I

Translating the Modern: A Walk Around Santiniketan, Part I

collection stories

Translating the Modern: A Walk Around Santiniketan, Part IChaiti Nath The City as a Museum, Kolkata 2025’s tribute to the innovations in Bengal Architecture begins with a series of programmes exploring the unique architectural and cultural sites of Santiniketan and some terracotta shrines in its nearby villages. We approach both not as static monuments and sites but as living, evolving experiments. |

Radha Charan Bagchi

Uttarayan Santiniketan (detail)

Watercolour on paper, 10.0 x 15.0 in.

Collection: DAG

|

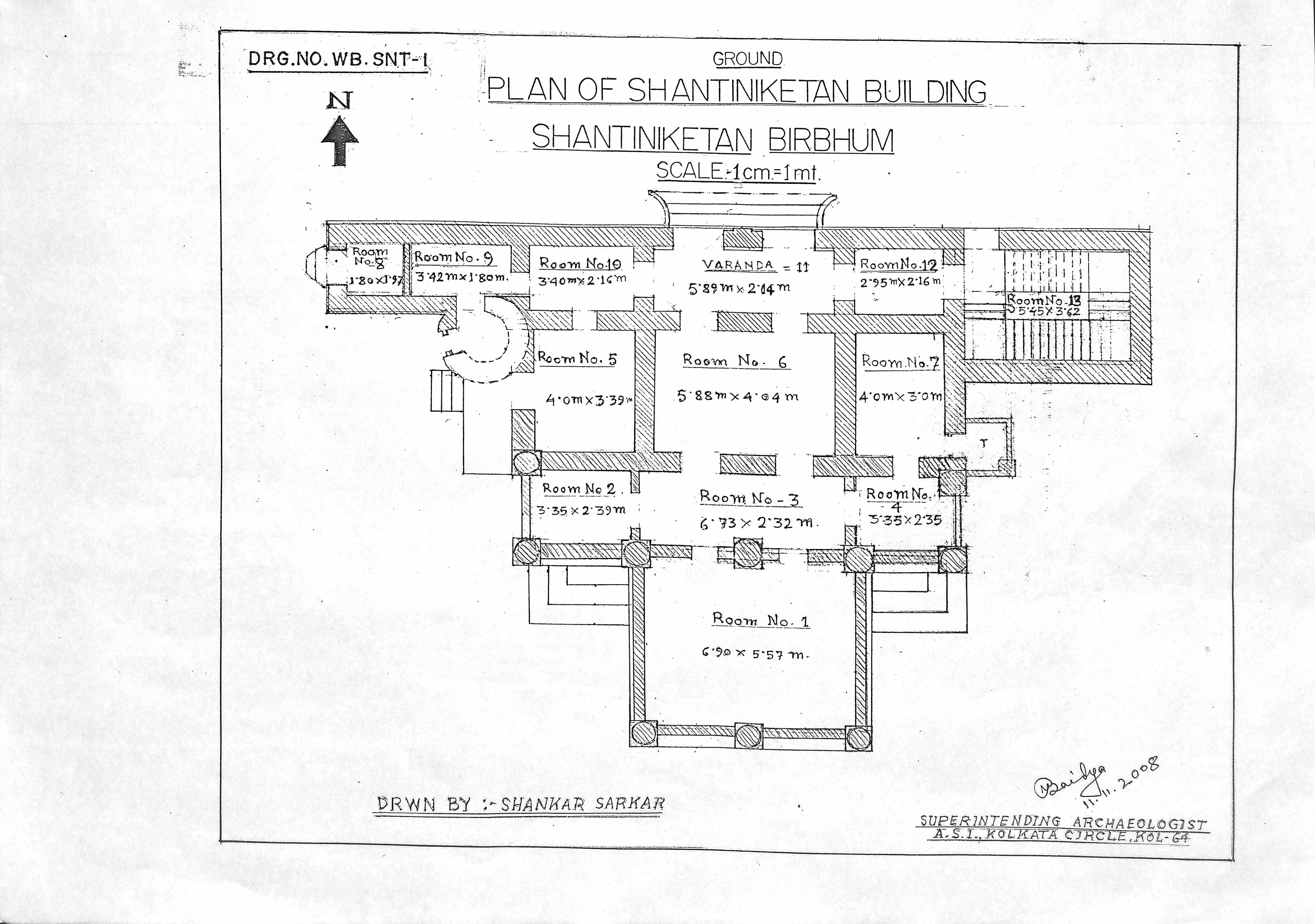

The story of this place begins in 1862, when Maharshi Debendranath Tagore, a leading proponent of the Brahmo Samaj, arrived at a tract of land in Bhubandanga, a remote rural area in the eastern province of Bengal in British ruled India. Drawn to its serenity, he established an ashram around the sacred Chhatimtala (Under the Saptaparni, or Milkwood tree) meditating ground, building Santiniketan Griha in 1873—the oldest building and the namesake of this abode of peace. It was here that a young Rabindranath Tagore, Debendranath’s son, first connected with the land, a connection that would deepen throughout his life. From 1901 onwards, he began to actively shape Santiniketan, driven by a constellation of influences: his aversion to conventional ‘cage-like' classrooms, a pantheistic view of nature as divine, and the vibrant, intercultural atmosphere of the Bichitra Club at his family home in Calcutta. His vision was to accommodate a fully working residential school and studios, multi-format cultural centres including spaces for leisure and informal gatherings, teachers and staff quarters in the form of Pallis (or, residential communities) and ultimately, a truly 'Eastern University'. |

|

|

Plan of Santiniketan Griha

Collection: Rabindra Bhavana Museum

Rathindranath Tagore

Untitled

5.2 x 3.2 in.

Collection: DAG

Santiniketan Griha, 2025

Rabindranath Tagore with members of his family

Image courtesy: Wikimedia Commons

Tagore’s core architectural principle was a radical communion with the environment which appealed to both his Indian and global artist-collaborators. Alongside his son, designer and landscape artist Rathindranath, the poet’s Visva Bharati as a ‘tangible poem’ was given shape by figures like Nandalal Bose and Ramkinkar Baij, while the self-taught architect Surendranath Kar translated his philosophy into built form. They were joined by international contributors like Japanese wood sculptor Kintaro Kasahara, along with lesser-known artists and artisans like Pratima Devi, Gouri Bhanja, Vamana Rao, Narasinghlal, and Vinayak Masoji, among others. |

William Winstanley Pearson

Boys at Examination

From the 1916 publication Shantiniketan: The Bolpur School of Rabindranath Tagore

Image courtesy: Wikimedia Commons

Amalnath Chakladar

Untitled (Saithiya Baul Sampradaya, Birbhum)

1965-86, Watercolour and gouache on paper, 18.7 x 24.7 in.

Collection: DAG

The team’s vision began with conceiving small-scale structures that resonated with the expansive horizons and laterite terrains of Rarh Bengal, integrating diverse architectural forms seamlessly into their natural surroundings. The minimalist approach towards built classrooms was not merely an aesthetic decision but a radical rethinking of the colonial and authoritarian models of education. In rejecting the monolithic and alien vocabulary of imperial design, Tagore articulated a critique of hegemonic Western modernity through the plural aesthetics of Santiniketan. The outcome was a syncretic architectural language—an innovative, modern yet Pan-Asian idiom grounded in the material and visual cultures of the East. |

|

As one walks from Santiniketan Griha toward the Gour Prangan area of Patha Bhavana, a sequence of thoughtfully articulated open-air learning spaces gradually reveals itself through the arched Madhabibitan trellis, or Madhabilata arbours. These include designated class zones organised around a bedi—a raised platform for the teacher, typically shaded by a tree canopy—and a reinterpreted clock tower known as the Ghanta-Talla. Serving as the timekeeper for the entire Ashrama complex, this structure evokes the modest form of a Buddhist Torana and houses a locally cast bell. Further along the path stands Chaiti, a mud-built pavilion derived from vernacular hut architecture that once functioned as both an art display and a community notice board. |

|

|

Nandalal with students inside Dinantika

Collection: Rabindra Bhavana Museum

Music and Fine Arts class together at Kala Bhavana with long windows apt for lighting rooms with low seating.

Collection: Rabindra Bhavana Museum

The quiet profundity of these modest spaces lies in their intentional design and lived purpose. Among the imaginatively conceived sitting arcades, arched wells, and intimate Sukho-poth (pleasure paths) for community residents stands a notable example: Dinantika, an octagonal, two-storied structure designed by Surendranath Kar. Adorned with frescoes by Nandalal Bose and his students, it was conceived as a space for evening gatherings over tea. Within this atmosphere, where conscious creative collaboration shaped the cadence of daily life, the building’s circular seating embodies an architectural expression of shared dialogue and egalitarian exchange. |

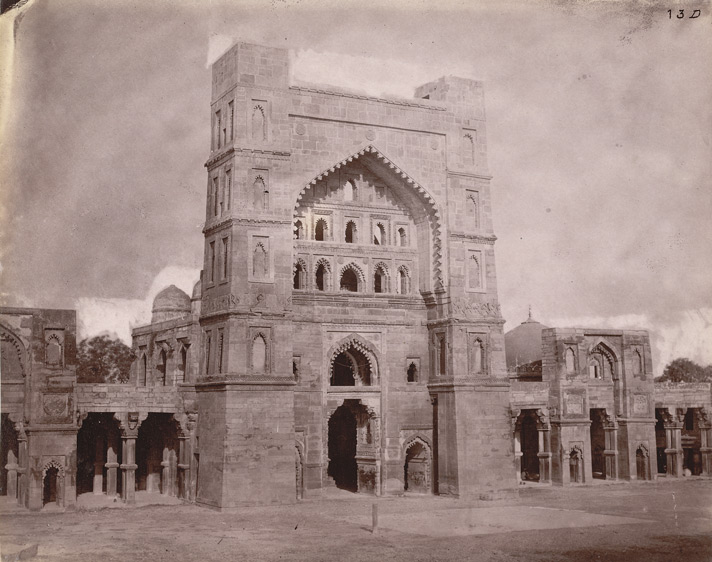

Joseph D. Beglar

Atala Masjid at Jaunpur (Uttar Pradesh, India)

1870s

Image courtesy: Wikimedia Commons

Singha Sadan

Encircled by these smaller structures stands the imposing Singha Sadan (1928), flanked by the Purba and Paschim Toranas and later complemented with gazebos to accommodate an expanding number of students and classes. While its interior served as a sports room, the principal façade and arched gateways reflect the architectural idiom of the Atala Devi Mosque of Jaunpur, Uttar Pradesh. Opposite it, the old library building, with its open, south-facing veranda, is richly adorned with Jaipur-style frescoes depicting scenes of Ashrama life and the surrounding village. These murals, executed by Nandalal Bose and his students, represent some of the earliest examples of painted surfaces within the Santiniketan precincts. |

|

The road extends into a lane, where two seminal institutions stand as guardians of Santiniketan’s mural legacy. The first, Cheena Bhavana, embodies Tagore’s wider pan-Asian vision. Within its interiors lies Nandalal Bose’s monumental fresco, The Temptation of Mara, depicting the Buddha’s moment of enlightenment and created in collaboration with Gouri Bhanja. At the upper level of its ground-floor veranda, Vinayak Masoji’s mural of Chandalika complements this spiritual narrative. Further along stands Hindi Bhavana, home to one of Benode Behari Mukherjee’s celebrated masterpieces, Life of Medieval Saints. Painted when the artist was partially sighted, this fresco buono work is revered for its compositional brilliance and meditative rhythm, tracing the continuum of Bhakti saints in a flowing procession of faith and devotion. |

|

|

'Dehali’, photographed in 2025

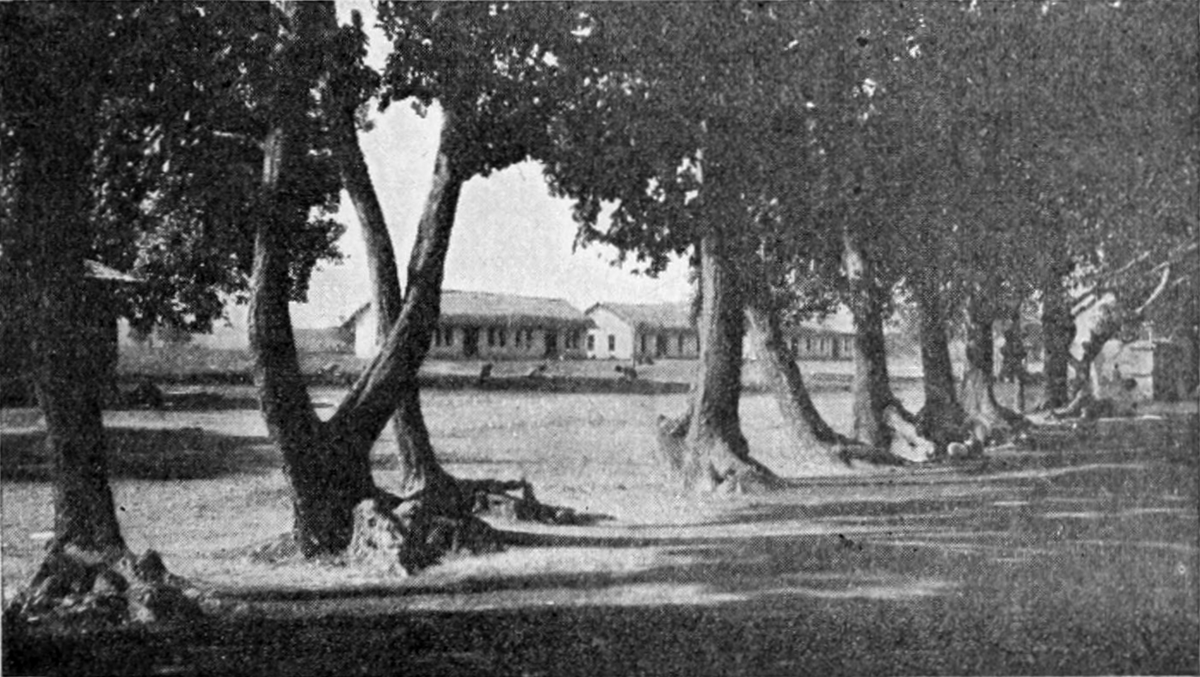

William Winstanley Pearson

The Sal Avenue

From the 1916 publication, Shantiniketan: The Bolpur School of Rabindranath Tagore

Image courtesy: Wikimedia Commons

A lane parallel to the Jahar Bedi runs through Salbithi—Tagore’s favourite avenue of Sal (Shorea robusta) trees—and culminates at two of his historically significant residences within the ashram: the single-story, thatched Dehali (1904) and the first two-story house by Tagore, Natun Bari (1906). Architectural historian Saptarshi Sanyal observes that Tagore’s evocative Bengali names for these spaces embody both his philosophical vision and the intrinsic nature of their design. The term Dehali combines deha (body) and ālɔy (shelter), aptly reflecting the school’s humble, formative years. Natun Bari (New House) served as the poet’s retreat during his most fertile creative phase. It was in the upper room of this dwelling, open to an infinite horizon, that Tagore composed and translated Gitanjali, the work that would bring him the Nobel Prize in Literature in 1913. |

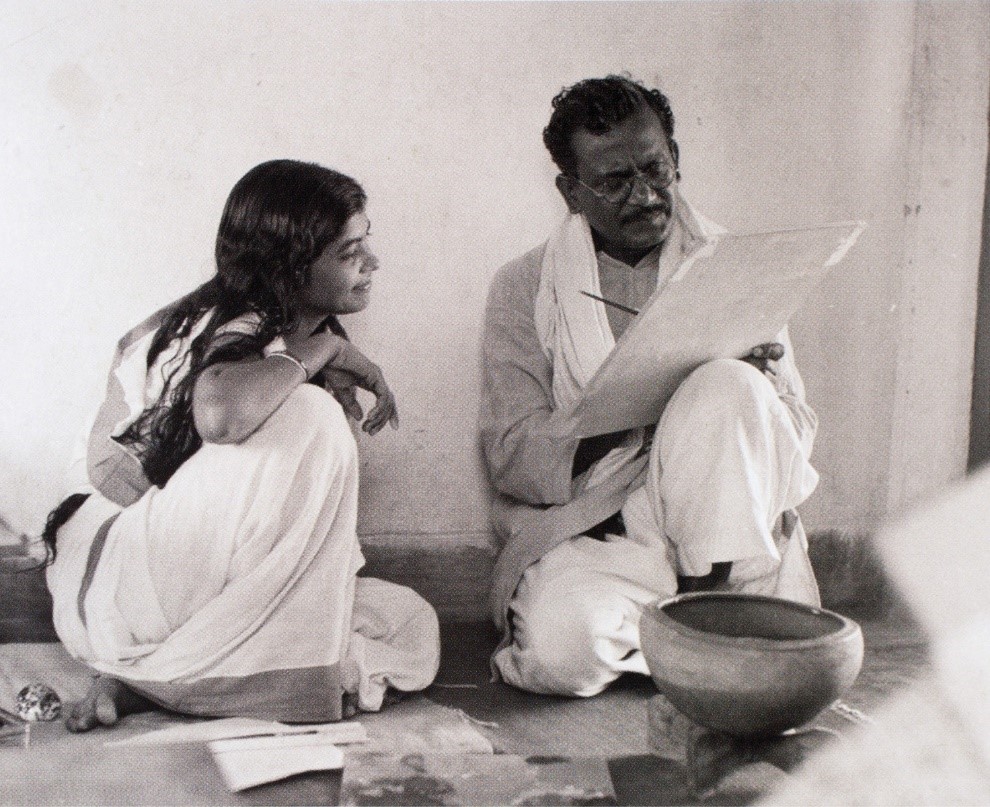

Nandalal Bose with a student at Kala Bhavana

Collection: DAG

The construction of Kalo Bari with Ramkinkar Baij

Collection: Rabindra Bhavana Museum

Interiors of Nandan, now housing the library, museum, archives and administrative offices of Kala Bhavana, photographed in 2025

Photographer: Sarnali Dutta

To the West of Singha Sadan, the road takes one to the precincts of Kala Bhavana and Sangeet Bhavana. Standing as a sentinel at this creative crossroads is the Kalo-Bari – a quintessential example of Santiniketan's material experimentation. Its striking black exterior is coated with a mixture of tar, manganese, and albumen (egg white), and its walls are adorned with Bharhut, Mamallapuram, Harappan, Assyrian and Egyptian folk and archaeology-inspired bas-reliefs created by students under the guidance of Ramkinkar Baij and Prabhas Sen, among others. The campus is a living open-air gallery, dotted with murals from different phases of its history by artists including Somnath Hore, Benode Behari Mukherjee, K.G. Subramanyan, Rudrappa Hanji, and Radha Charan Bagchi, while the great monumental sculptures of Ramkinkar root the entire experience in a powerful, three-dimensional presence. Architecturally, Kala Bhavana evolved by constructing newer spaces and studios, according to the needs of teachers and students. |

|

Writing about Natun Bari, Tagore would say that it was '…a beautiful place, far away from the contamination of town life […] I knew that the mind had its hunger for the ministrations of nature, mother-nature, and so I selected this spot where the sky is unobstructed to the verge of the horizon. There the mind could have its fearless freedom to create its own dreams and the seasons could come with all their colours and movements and beauty into the very heart of the human dwelling.' |

|

|

Natun Bari (New House), Santiniketan

Image courtesy: Wikimedia Commons

Dinakar Kowshik recalls how the architecture of Nandan was designed to harness natural light through a large glass facade, eliminating the need for artificial illumination during the day. The building, which now houses the Kala Bhavana library, archives, galleries, and museum, draws inspiration from South Indian temple architecture. Its spatial rhythm is defined by a progression of verandas that facilitate cross-ventilation and lead into the horizontally aligned halls. More than a static museum, this is a living campus where the legacy of its founders is continually reinterpreted, and artistic practice unfolds each day within the very spaces that once nurtured their creativity. |

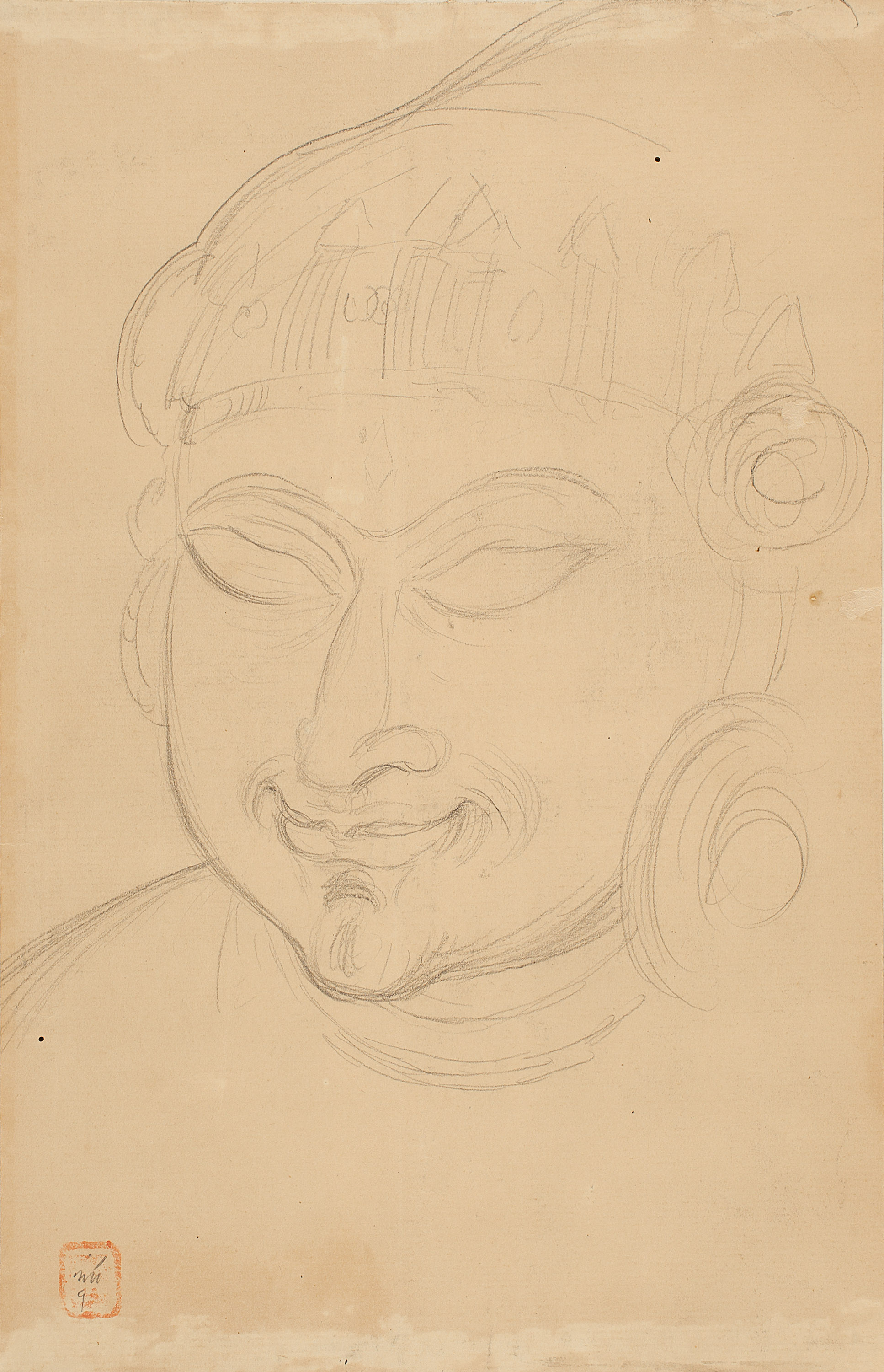

Nandalal Bose

from the Konark Album

Collection: DAG

Konarak Building, Santiniketan

Radha Charan Bagchi

Uttarayan Santiniketan

Watercolour on paper, 10.0 x 15.0 in.

Collection: DAG

Walking back towards Santiniketan Griha, one encounters the Uttarayan complex across the road—a demarcation that did not exist when these buildings were conceived. This cluster of five residences, designed primarily by Surendranath Kar in collaboration with Rathindranath Tagore, Nandalal Bose, and Kintaro Kasahara between 1919 and 1938, housed the poet, his peers, and guests, representing the pinnacle of Santiniketan's architectural eclecticism. The first of these, the single-story Konarka (Slanting ray of sun, 1918), was designed to capture the early sun's slanting rays, has its main living space opens onto a long, east-facing veranda. This projected veranda functioned as the home's primary entrance, a deliberate departure from conventional architectural layouts. |

Udayan Building, Santiniketan

The following residence, Udayan (‘The Dawning,’ 1928) was the most elaborate of the Uttarayan residences, taking nearly a decade to realise. Its architectural vision drew deeply from the austerity of Buddhist vihara colonnades, the intricate jharokha motifs of Gujarati havelis, the refined timber panelling characteristic of Japanese design, and subtle echoes of Angkor Wat’s wooden railings. What makes Udayan exceptional is its deft superimposition of these eclectic influences over several levels, maintaining both spatial coherence and aesthetic equilibrium. The resulting residence embodies a collaborative modernism that asserted an Indian architectural identity, distinct from and resistant to homogenous Western paradigms. |

|

Thus, while the entire Santiniketan enclave stands as a sweeping Gesamtkunstwerk—a total work of art—the Udayan cluster earns this distinction on its own terms. Its design extends beyond the building into an elaborate landscape, integrating arched arbours as living gateways, geometric lakes, a sculptural fountain, stone gardens, and a cave-like studio with exquisite wooden interiors and upholstery, all connected by a network of pleasure paths. This virtuoso synthesis of architecture, art, woodwork, and civil engineering epitomises what scholar Arunendu Banerjee has rightly termed the 'Santiniketan Golden Era of the Total Art Movement'. |

|

|

|

This article charts the route that will be taken for The City as a Museum, Kolkata's Santiniketan chapter on 28 November, 2025. To learn more about the built spaces at Santiniketan, read the second part of the article: click here |

|

|