Revisiting The Delhi Durbar Exhibition of 1903 at Qudsia Bagh

Revisiting The Delhi Durbar Exhibition of 1903 at Qudsia Bagh

Revisiting The Delhi Durbar Exhibition of 1903 at Qudsia Bagh

collection stories

Revisiting The Delhi Durbar Exhibition of 1903 at Qudsia BaghSumona Chakravarty The three Delhi Durbars, of 1877, 1903, and 1911, left an indelible trace on the urban landscape of the city of Delhi—be it the expansion of the railways or the plans for the new capital of the British colonial empire in India, which was being moved there from Calcutta (now, Kolkata) in 1911. However, it was the 1903 edition that had a far-reaching impact on the trajectory of art across the subcontinent—from Calcutta to Lahore. |

Jaali from Sidi Sayed Mosque, Ahmedabad

Image courtesy: Wikimedia Commons

|

As part of the Durbar of 1903 George Watt organised an exhibition of Indian Art at Qudsia Bagh, which is a garden complex in Old Delhi, built in the mid-eighteenth century for Qudsia Begum, the mother of the then Mughal Emperor Ahmed Shah Bahadur. The show's claim to fame, as professed in the exhibition catalogue, was that for the first time, in the history of similar public expositions on Indian art, the objects were not arranged by their region of origin or the manufacturers that produced them, but that they were systematically collected and scientifically organised by medium and technique. This new system of classification allowed for the emergence of a new class of art objects—elevated to the status of the Fine Arts. |

|

|

The Great Exhibition, 1851 (London)

Image courtesy: Wikimedia Commons

The Great Exhibition, London, 1851The regional emphasis of earlier exhibitions, such as the Great Exhibition of 1851 in London—housed within the grand glass pavilion at Hyde Park—was expressed through a series of ‘courts,’ each styled to represent a different region and competing in splendour and display. With performers cast as village artisans, the exhibition sought to construct an image of India that was at once authentic and fantastical. Celebrated by the public as a ‘tastemaking’ enterprise, it countered the relentless march of industrial modernity by staging a revivalist vision centred on rural craft traditions. |

Interior of the Crystal Palace, where the Great Exhibition of 1851 took place

Image courtesy: Wikimedia Commons

South Kensington Museum

Image courtesy: Wikimedia Commons

These objects, somewhat haphazardly gathered from different corners of the subcontinent became the foundational collections of the South Kensington Museum (now the V&A) and the East India Company’s India Museum in Leadenhall Street. In India, many art schools were established in the years following this exhibition, with the professed desire of elevating the minds and skills of craftspeople in the region. These schools feature more prominently in the 1903 Durbar exhibition, where they are front and centre of the Imperial craft revival project. |

|

|

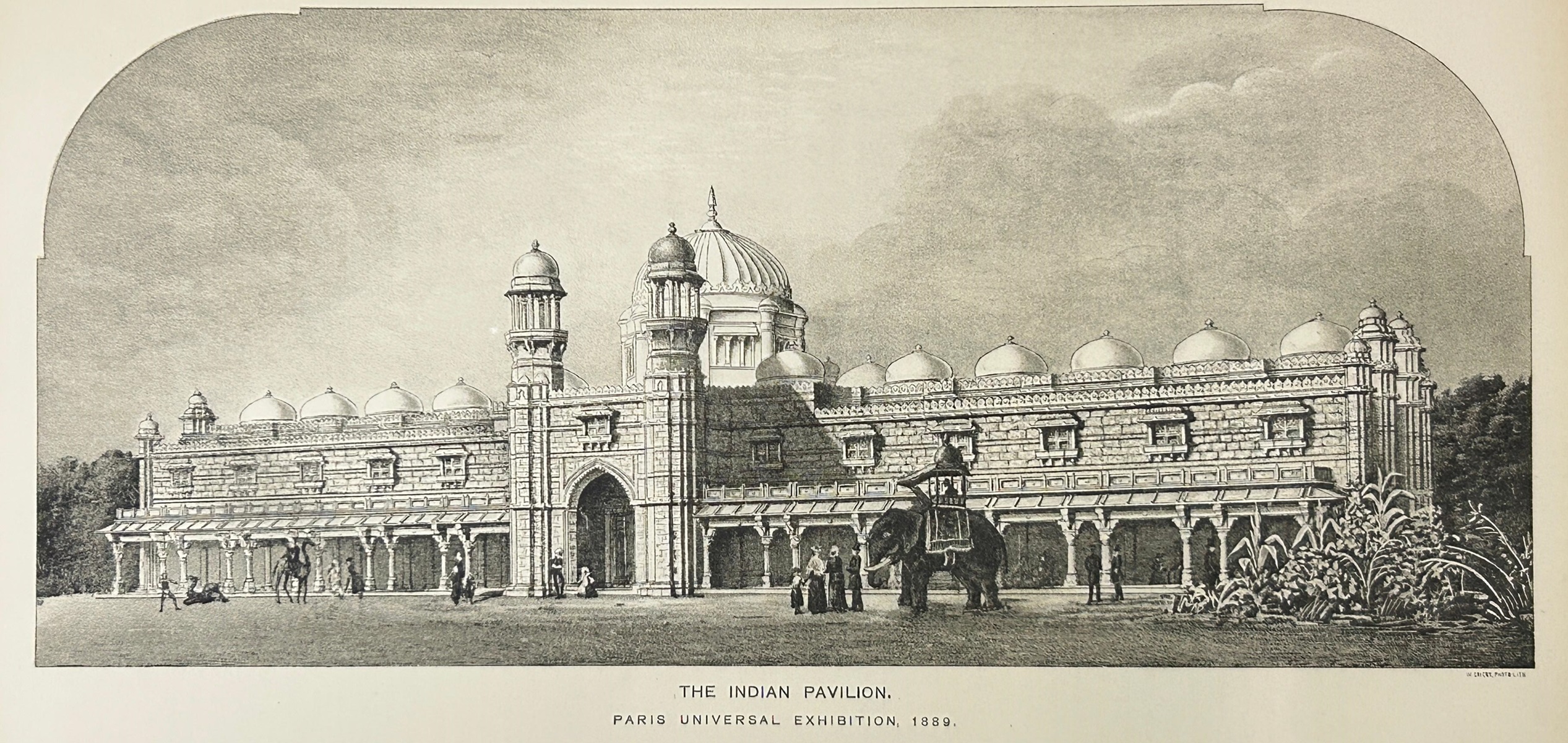

The Indian Pavilion

Paris Universal Exhibition, 1889

The Journal of Indian Art, Vol. III (October, 1889), No. 28

Collection: DAG Archive

Advertising poster for the 1889 World's Fair in Paris

Image courtesy: Wikimedia Commons

Universal Exhibition, Paris,1889In the meantime, the art schools struggled to establish themselves, and grand Imperial plans to save the Indian art traditions were waylaid by financial and political imperatives. In Paris, a world fair was organised in 1889 to mark the hundredth anniversary of the French Revolution. The British Indian Section received no funding from the British Government who had boycotted the event in solidarity with the monarchy. In response, a private committee stepped up to sponsor the pavilion, which ended up primarily showcasing the interests of traders and manufacturers from both Britain and India. Each group maintained separate areas within the pavilion, making commercial gain the principal focus rather than cultural diplomacy or artistic exchange. Notably, Mohandas Gandhi, a young barrister-in-training in London at the time, visited the Paris world fair, encountering first-hand the contestations between industrial manufacturing and traditional crafts, and the charged debates between the colonial centre and the colonies. |

|

|

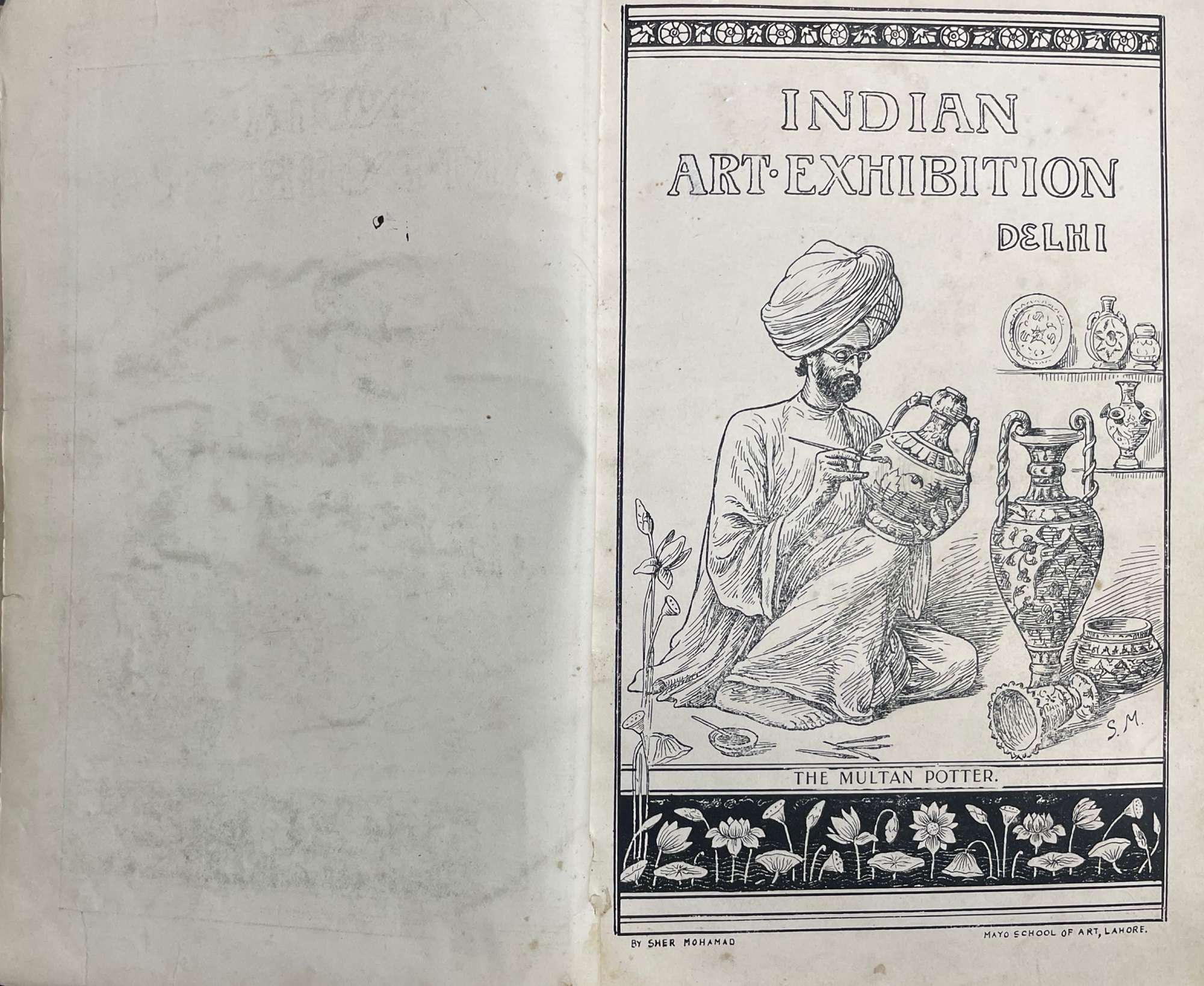

George Watt

Indian Art at Delhi, 1903: Being the Official Catalogue of the Delhi Exhibition, 1902-1903

Superintendent of Government Printing, Calcutta, India

Collection: DAG Archive

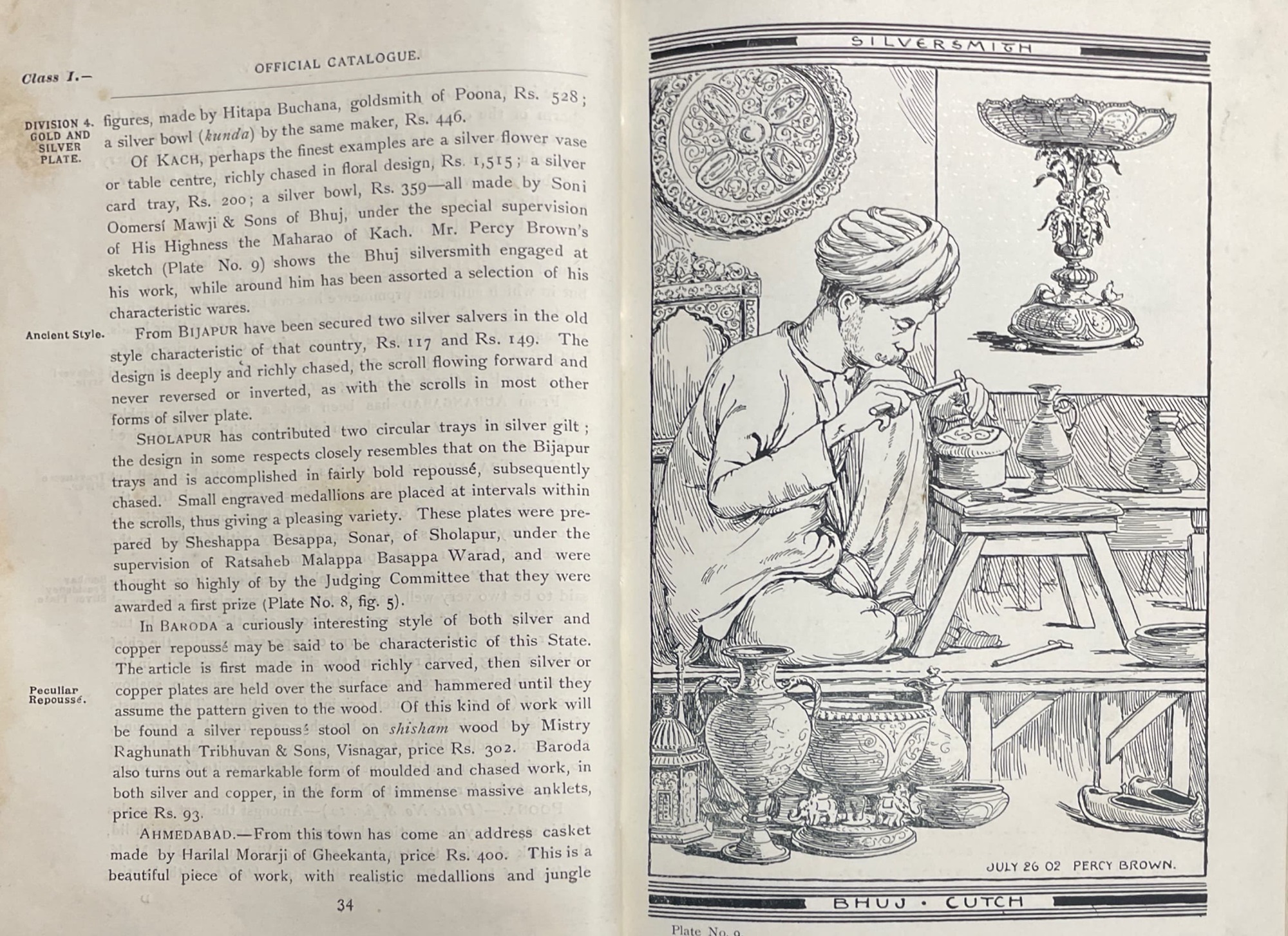

Percy Brown

Silversmith, Bhuj, Cutch

from George Watt's Indian Art at Delhi, 1903: Being the Official Catalogue of the Delhi Exhibition, 1902-1903, Superintendent of Government Printing, Calcutta, India

Collection: DAG Archive

Percy Brown

Enamellers, Pertabgarh, Rajputana

from George Watt's Indian Art at Delhi, 1903: Being the Official Catalogue of the Delhi Exhibition, 1902-1903, Superintendent of Government Printing, Calcutta, India

Collection: DAG Archive

Indian Art Exhibition, Delhi,1903The exhibition was led by the Viceroy, Lord Curzon, and organised by George Watt, a botanist who had previously managed exhibitions in Calcutta (1883) and London (1886). He was supported by Percy Brown, Principal of the Mayo School of Art in Lahore, who helped coordinate a wide network of colonial officials. Museum curators, art school principals, District Officers, and Tahsildars were given the task of collecting traditional artefacts and overseeing the production of new ones. These new items had to avoid what officials saw as the ‘degrading’ effects of modernisation. The rulers of the Princely States also played a key role in supporting the exhibition. Some of the objects were made by artists trained in art schools, often from elite backgrounds, while others were created by traditional craftspersons from hereditary communities. The official catalogue focused on showcasing these craftspersons at work, using illustrations by Percy Brown. This interest in the ‘authentic’ rural artisan was a common theme in exhibitions from the Great Exhibition in London in 1851 to the Delhi Durbar of 1903. . |

George Watt

The Exhibition Buildings

Indian Art at Delhi, 1903: Being the Official Catalogue of the Delhi Exhibition, 1902-1903, Superintendent of Government Printing, Calcutta, India

Collection: DAG Archive

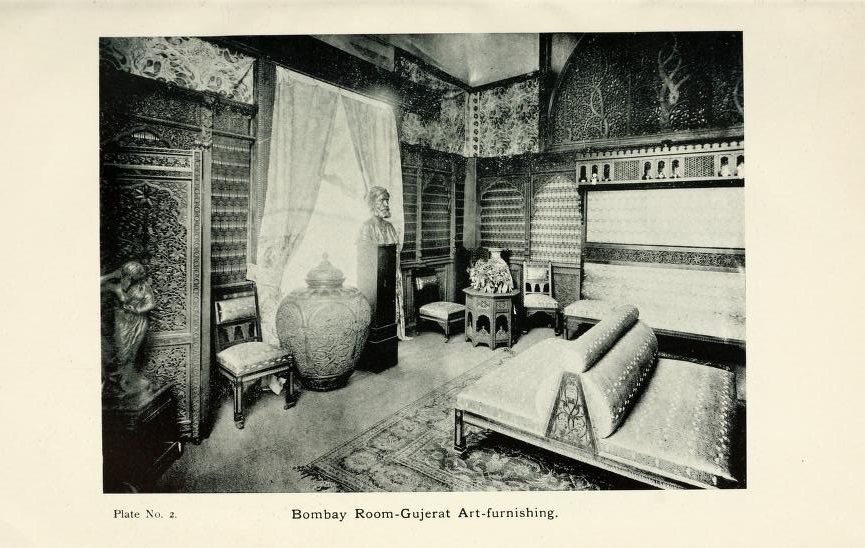

George Watt

Bombay Room-Gujerat Art furnishing

Indian Art at Delhi, 1903: Being the Official Catalogue of the Delhi Exhibition, 1902-1903, Superintendent of Government Printing, Calcutta, India

Collection: DAG Archive

The Order of ThingsThe exhibition’s pavilion was designed in the Indo-Saracenic style—an architectural mode rooted in Mughal traditions and later reimagined by British architects such as Robert Chisholm, who fused diverse regional and religious elements. This hybrid style had already been employed in earlier India pavilions at international exhibitions. The façade of the structure featured tiles crafted by potters from Lahore, Multan, and Jaipur, complemented by frescoes executed by students of the Lahore Art School. Within the pavilion, Watt and Brown developed an elaborate classificatory scheme, organising the interior into carefully delineated sections to correspond with their system of categorisation. The organisers hoped that these categories would become the dominant system for understanding Indian art, updating and expanding the work done by George Birdwood in his widely referenced publication ‘Industrial Arts of India’ (1880), which had so far established the collecting and organising logic for museums and collectors. |

George Watt

Horn, Shell and Featherwork

Indian Art at Delhi, 1903: Being the Official Catalogue of the Delhi Exhibition, 1902-1903, Superintendent of Government Printing, Calcutta, India

Collection: DAG Archive

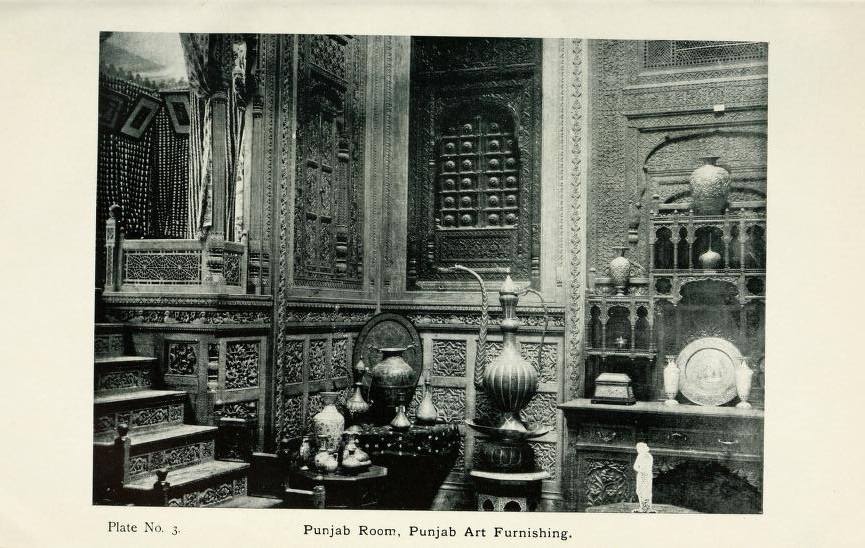

George Watt

Punjab Room, Punjab Art Furnishing

Indian Art at Delhi, 1903: Being the Official Catalogue of the Delhi Exhibition, 1902-1903, Superintendent of Government Printing, Calcutta, India

Collection: DAG Archive

Objects were organised by medium: metal, stone, glass, wood, ivory, lac, textiles, embroidery, carpets; a total of ten categories, with the final category being Fine Arts. The accompanying catalogue detailed each medium, providing fascinating insight into the material culture of the time, while also betraying the forced artifice of many of the objects displayed, which were designed and supervised by the organisers to meet their standards of authenticity and quality. Within each category, hierarchies were imposed, and the objects judged to be of the highest quality were strategically positioned near the Fine Arts section, reinforcing a sense of progression and artistic refinement. |

|

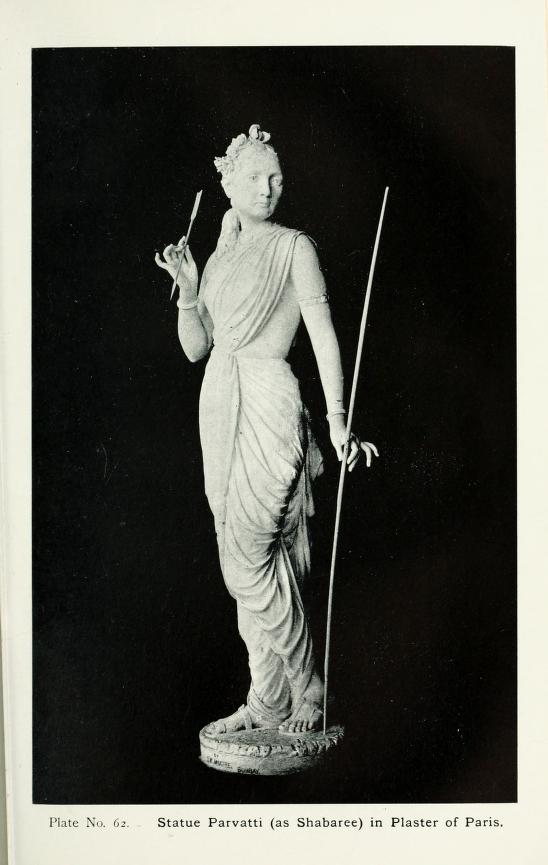

Of the Higher Arts – G. Mhatre The Fine Arts category was given pride of place, in the centrally located great transept, though Watt bemoaned the lack of talent in the field. He asserted that perspective, shadow and atmosphere were skills essential to the ‘higher arts’ that had not yet been cultivated in Indian artists. In fact, in earlier exhibitions such as World's Columbian Exposition in Chicago in 1892, where Raja Ravi Varma, who was at the time one of the foremost painters in the country, submitted 10 paintings, only to be relegated to the ethnography section. In 1903 however, Bombay-based artist G. Mhatre’s now iconic To the Temple sculpture—of a gracefully poised lady carrying a plate of offerings—was awarded a first prize in the sculpture section of the fine arts category, marking a shift in established hierarchies. |

|

|

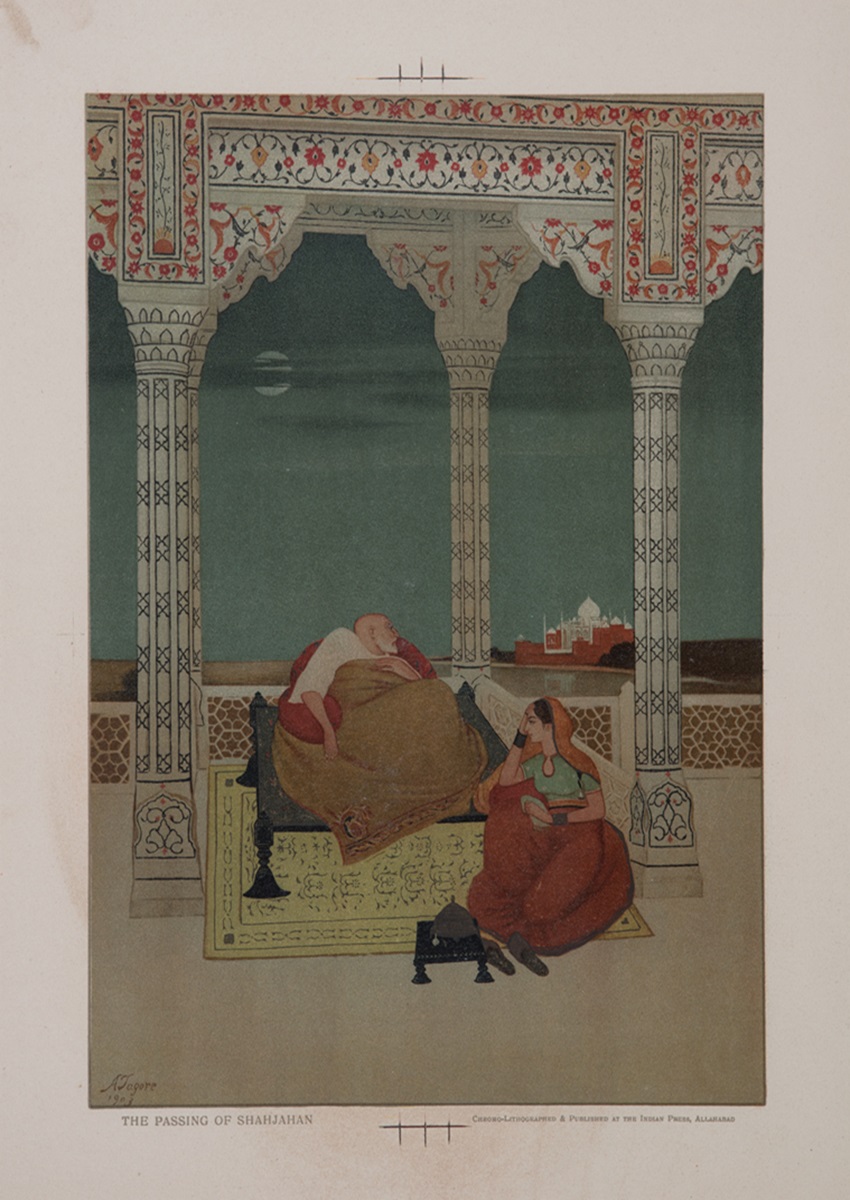

Abanindranath Tagore

The Passing of Shah Jahan

1903, Chromolithograph on paper, 15.0 x 10.0 in.

Collection: DAG

George Watt

Statue Parvatti (as Shabaree) in Plaster of Paris

Indian Art at Delhi, 1903: Being the Official Catalogue of the Delhi Exhibition, 1902-1903, Superintendent of Government Printing, Calcutta, India

Collection: DAG Archive

New Indian Art – Abanindranath TagoreIn the painting section the medal for second place went to the young Abanindranath Tagore, for his painting The last days of Shah Jehan which was classified under the ‘Muhammedan Painting’ section of the Fine Arts Category. He had eschewed his academic, art school training in painting, to turn to the Mughal miniature traditions, Ajanta paintings and Japanese inspired wash style of water colours. This award legitimised this new style, and Tagore went on to train his students at the Calcutta art college in this manner of painting, leading to the emergence of the widely prolific Bengal School of Art. For all the changes that the exhibition heralded, it is worth noting that no award for the first prize was given in the painting category. This was a pointed message from the organising committee on the perceived shortcomings of Fine Arts in India. |

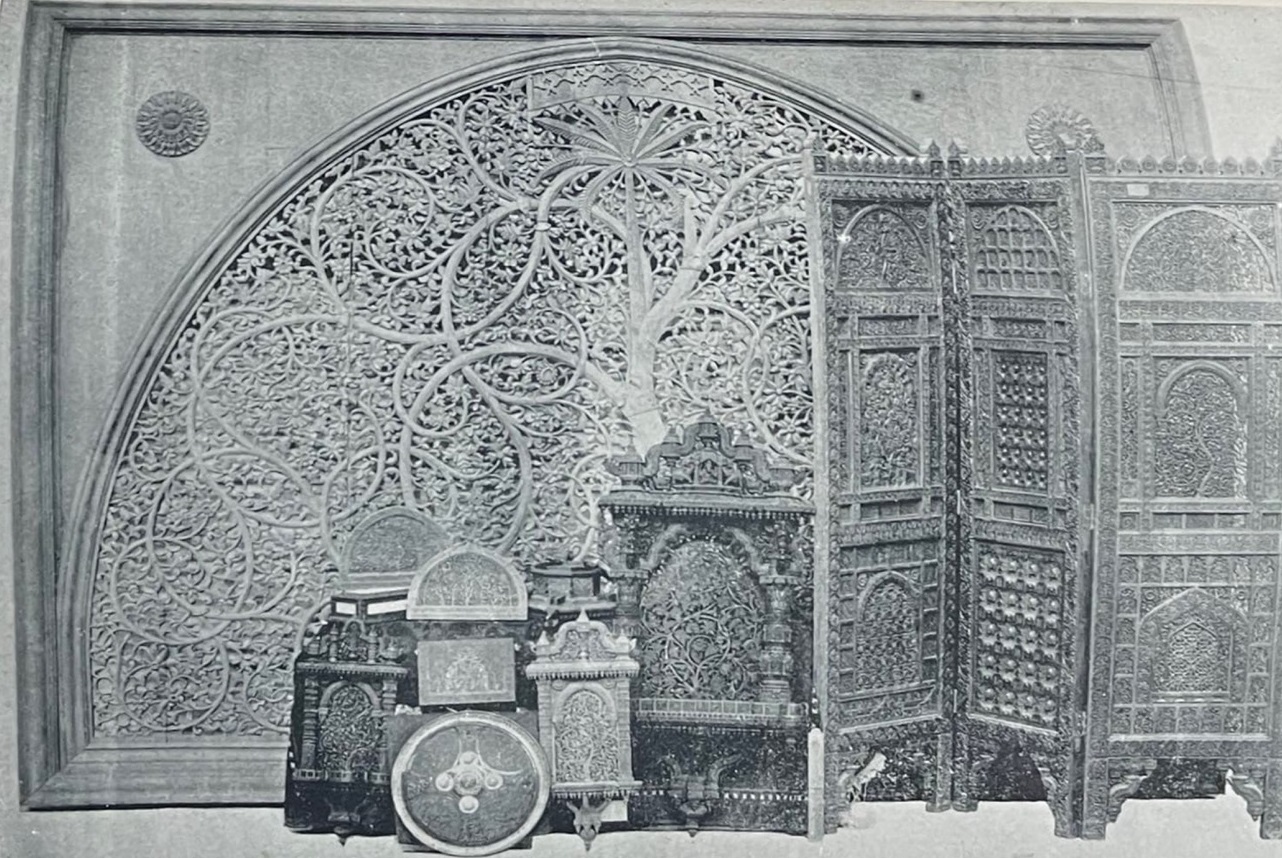

George Watt

Wood Carving of Ahmedabad

Indian Art at Delhi, 1903: Being the Official Catalogue of the Delhi Exhibition, 1902-1903, Superintendent of Government Printing, Calcutta, India

Collection: DAG Archive

Art of Ornament – The Sidi Saiyyed JaaliAnother highlight of the exhibition, awarded a first prize, was the intricately reproduced semi-circular screen from the Sidi Saiyyed Mosque in Ahmedabad. The motif of the tree, and the ornamental jaali or lattice surrounding it had been copied and carved in wood by the students of Principal Cecil Burns of the Sir J. J. School of art in Bombay and was placed in one of the many special nooks that were dispersed across the exhibition pavilion. These nooks, named after the regions they represented exemplified the ‘adaptability of the various better-known styles of Indian Art, to modern household furnishing and architectural decoration’. And while many of these richly produced objects ended up in museums, the Sidi Saiyyed jaali became a recognisable feature of Indian architecture. While placed adjacent to the Fine Arts sections, these arts would retain their somewhat diminutive ‘decorative’ association, and artists would be allowed only limited and controlled access to the status of the higher arts. |

Abanindranath Tagore

Collection: DAG

The Order of BusinessWhile the exhibition contributed in many ways to the development of the arts the exhibitions were fundamentally a commercial enterprise, with the Main Sale Gallery—with objects ranging from metal ware to Fine Art—as the central proposition. As Saloni Mathur writes in ‘India by Design’, 1903, the year of this exhibition, was also the year when ‘the nationalist historian R. C. Dutt would challenge such spectacles, and the conditions of economic dependence they concealed… His account in turn influenced the swadeshi (homemade) campaign in Bengal to boycott British goods and promote indigenous products, which reached its apex in 1905.’ |

|

Abanindranth Tagore’s Muhammadan style, rechristened the ‘The Bengal School’, would be backed by leading art critics as a pioneering force behind the revival of Indian art, and the creative impetus of the anticolonial movement. The craftsman would be claimed by Gandhi and his followers as a central figure of the national struggle and exhibition-making would become a key feature of the Congress’ public campaigns. The post-independence nation-building project would adopt the design of the Sidi Saiyyed jaali as an icon of its new school of management in Ahmedabad. In this seemingly linear narrative of a colonial to nationalist transformation of ideas around exhibitions, Indian art and craft, Mhatre, the gold medallist sculptor, cuts a contrarian figure. He continues to strive to excel in European academic art traditions, writing to George Birdwood to help him fund his travel to London, which he believed was the epicentre of Fine Art, revealing that new classifications and hierarchies were quite immovable, despite the transformations. |

|

|