Rani Chanda on Nandalal Bose, Jamini Roy and Mukul Dey

Rani Chanda on Nandalal Bose, Jamini Roy and Mukul Dey

Rani Chanda on Nandalal Bose, Jamini Roy and Mukul Dey

Rani Chanda on Nandalal Bose, Jamini Roy and Mukul Dey

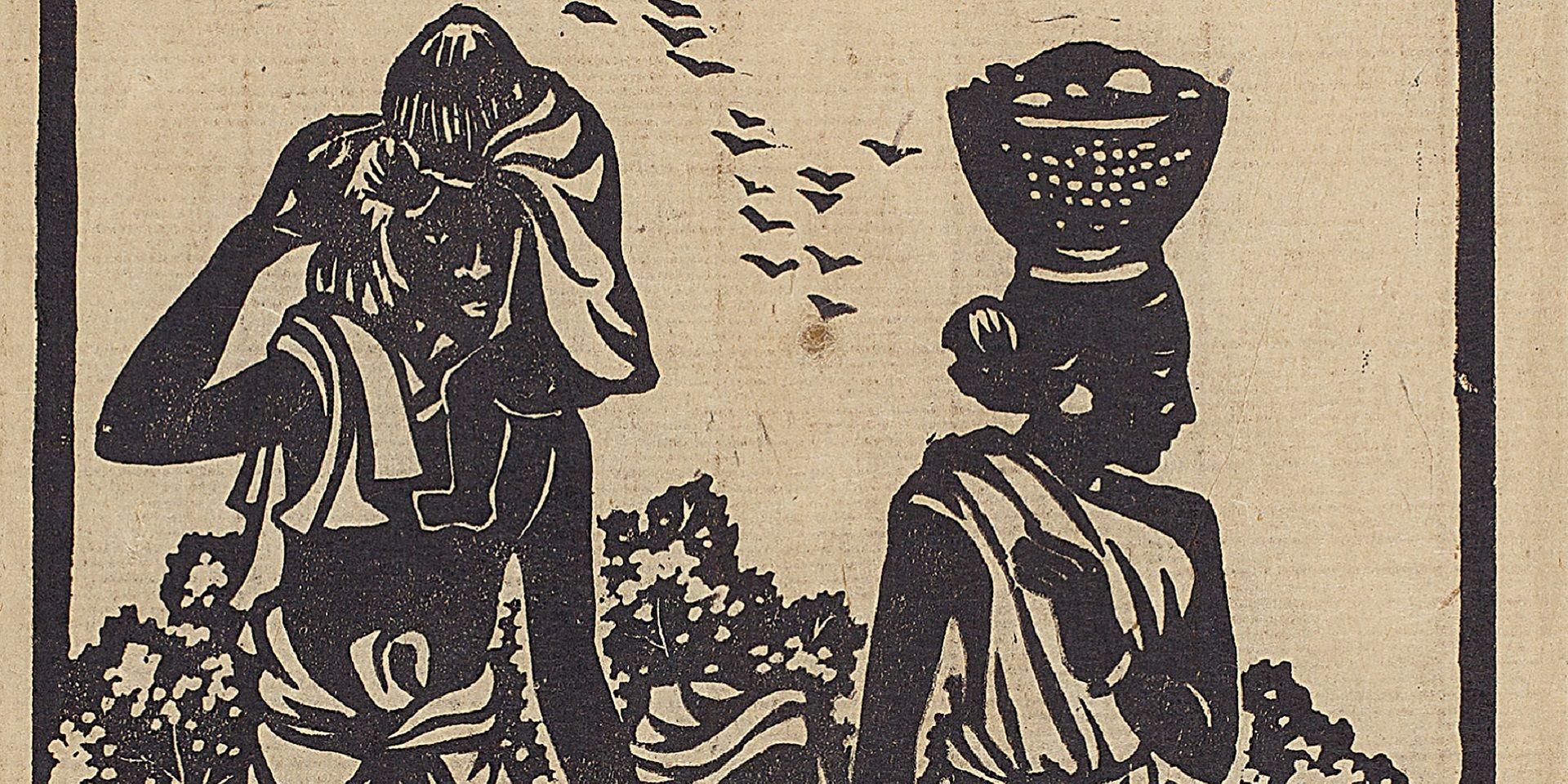

Rani Dey, Untitled (detail), Woodcut on newsprint paper, 8.5 x 6.0 in., 1938. Collection: DAG

Rani Dey (later, Chanda, 1912—1997) the memoirist is remembered more fondly by the Bengali art public instead of Rani Chanda the artist. An early student of Nandalal Bose, and the sister of one of the foremost printmakers of his day, Mukul Dey, Rani’s life was shaped by an atmosphere of artistic creativity from a young age.

On witnessing Rani’s impeccable memory and ability to retain details, Abanindranath Tagore named her ‘Srutidhari’ (one who listens and remembers). The inner lives of people, the pulse of their times, and the cadences of the everyday come alive in Rani’s writings in a way that reveals the quiet perception of a gifted wordsmith.

Although we are left with only a few specimens of her artworks today, mostly from a portfolio of early linocuts published by Mukul Dey, by all accounts Rani was an inventive artist who had worked in various mediums like fresco painting, printmaking, and decorative arts like alpona. From her own memoirs we can glean Rani’s fondness for sketching, which led to collaborative ventures with master artists like Abanindranath, most of which is now considered lost. She also wrote about the endearing practice of exchanging postcards filled with scribbles and sketches with her beloved mentor Nandalal Bose.

In the translation which follows, Rani recounts her memories of painting alongside pioneering artists like Jamini Roy, Nandalal, and her elder brother, in a large airy home studio. Through her words the reader is drawn into an inspiring world of creative solidarity and free-flowing exchange. The piece is an excerpt from her tribute to Nandalal, the artist and the person whose influence Rani felt most closely, and of whom she writes, ‘he was the companion of all my joys and sorrows, a constant well-wisher—he was my friend’.

A photograph of Nandalal Bose. Collection: DAG

Manush Nandalal (Nandalal, the person)

Rani Chanda

Well, let me try and write about Nandalal Bose, the person.

To separate the individual from the artist becomes an almost impossible task when it comes to Nanda-da. In him one seamlessly merges into the other.

To everybody else he is ‘Master moshai’ [revered teacher], but he is Nanda-da for us. That’s what our elder brother (artist Mukul Dey) used to call him, and we had quite easily picked it up. I have known Nanda-da from a very young age. When baba passed away, I was just four years old. We were staying in Calcutta at the time, and Nanda-da used to drop by quite often. I recall the times he would lovingly pick me up in his arms and dote on me. I have always cherished the warmth of his affection.

A few years went by. Ma decided to go to Dhaka with me and my young siblings, and in some time Borda [elder brother] went abroad. On returning after a couple of years he joined the Art School [renamed as Government College of Art and Craft in 1951] in Calcutta as the Principal, and once again we were back in the city.

The principal’s living quarters were on the second floor of the Art School; an apartment built in the residential style preferred by the British sahibs. It was luxurious with four spacious rooms, a high ceiling, and thick walls. We soon began to use the west-facing drawing room as an atelier. We would simply sit on the floor and begin painting. The floor itself was divided into four large sections with faint lines of thread which were often used during construction to prevent the concrete floors from developing cracks.

|

Mukul Dey, Girls Dancing, Drypoint on paper, 14.0 x 9.5. Collection: DAG |

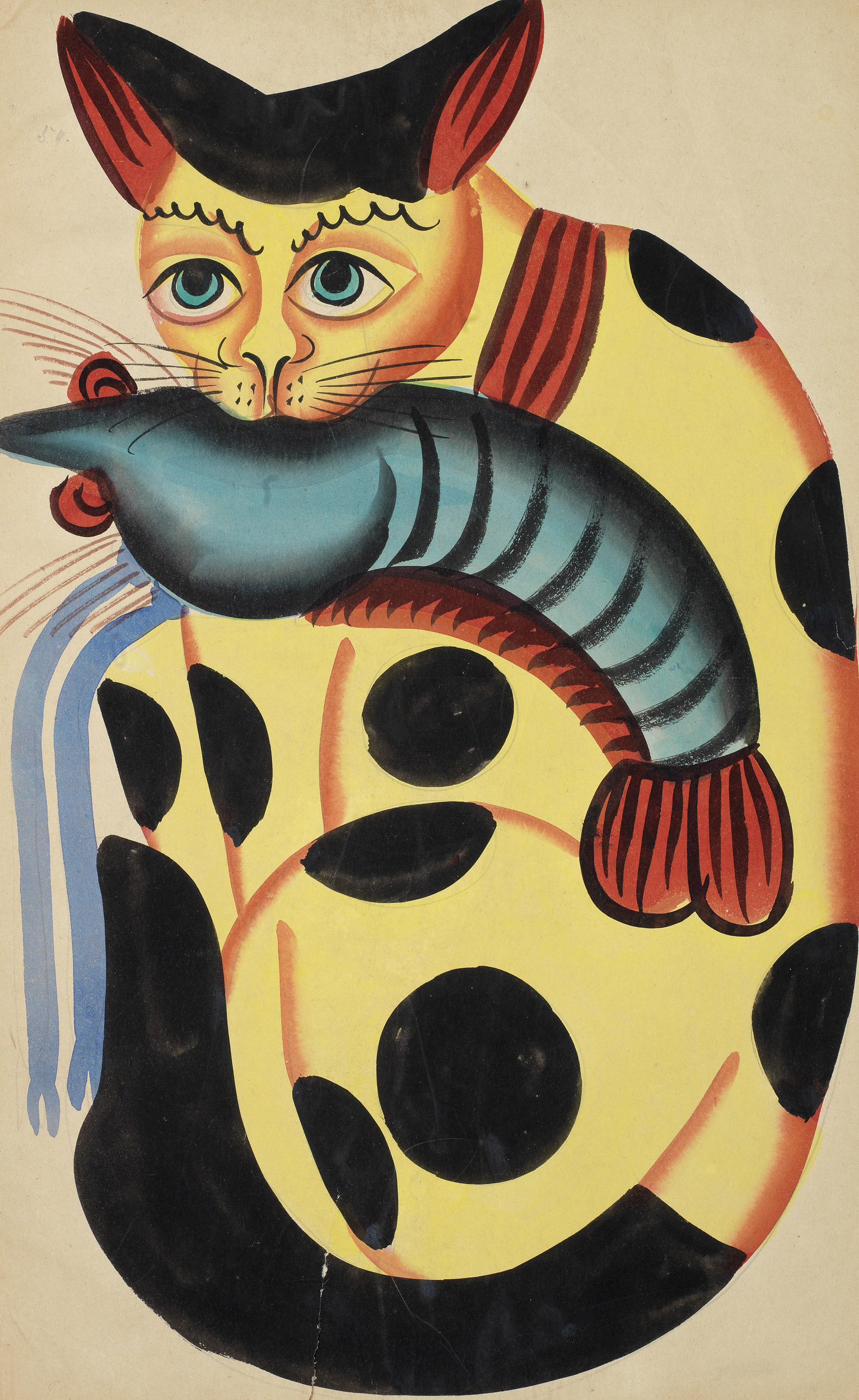

Around this time Jamini-da (Jamini Roy) used to live in a small, rented house, which hardly had enough space for him to work with things lying around (on the ground). He had already left behind his previous [academic] style and was presently absorbed in mastering the style of patachitra [scroll painting of Bengal].

|

Anonymous, Untitled (Cat Stealing Prawn), Water colour and graphite on paper. Collection: DAG |

Borda brought along Jamini-da to use a part of the room for his work, supplied him with plenty of paper and colours, and said, ‘Paint as much as you want’. Unperturbed by anything around him, Jamini-da would ceaselessly paint one pat after the other.

In another section of the room Borda would paint and draw whenever he could manage to get some free time, or on holidays. All the trappings of his trade would lie strewn on his part of the make-shift atelier.

Jamini Roy, Untitled, Tempera on cardboard, 15.0 x 27.2 in. Collection: DAG

I decided to lay claim to the empty space right next to Jamini-da. I had just taken up painting around this time, and naturally I was the one most enthusiastic at the prospect of working alongside such master artists. The fourth part of the room would lie unoccupied unless Nanda-da came to Calcutta— although during those years he would come quite often. And when he did arrive, Nanda-da would simply sit down to work on the floor segment I had chosen for myself. Sometimes, while chatting with Jamini-da, Borda would bring my works alive with colours by the touch of his paintbrush. I would lean over and watch the transformation unfold in rapt attention. Whatever I could glean from the expert movements of his brush each time, I would use to begin my work anew. With Nanda-da’s touch however, the canvas would become suffused with a certain verve that captivated me. Ever since, I have been under the spell of his artistic charm. It is as if there was magic in his fingers.

Nandalal Bose, Sketching in the Night/ Tourer Kotha, Ink and pastel on postcard, 2.7 x 3.2 in., 1953. Collection: DAG

Once Borda was copying a small-scale work onto a large paper canvas. In those days you would have to make wash paintings by fixing thick cartridge paper sheets in wooden frames. The scene slowly taking shape before my eyes was that of three generations of women going about their everyday ritual of bathing in the Ganga. In the early hours of the evening an old woman was sitting on the edge of the steps descending into the river [ghat], and appeared to be praying, a matronly figure had just emerged from the water and a young bride was still immersed neck-deep, perhaps in the hope of one more plunge before heading homewards. A peepal tree hunched along the bank had playfully stretched out its branches, casting a lively shadow on the rippling water. The sky overhead, the water and the earth stretched beneath it, everything came together to form one complete work of art, rich with details.

While Borda was finishing this painting, Nanda-da used to drop by, and would always make time to carefully look at my sketches and paintings. He would spend some time with us, chat with Borda and Jamini-da, and all the while his hands would be moving deftly, making bold strokes.

|

Mukul Dey, Drawing the net, Karatoa River, Pabna, East Bengal, Dry point on paper/ Collection: DAG |

I remember Borda asking Nanda-da many times to add some finishing touches to his canvas, but to no avail. The thought that something was missing from the painting kept worrying Borda. In a sense, the scene appeared to be complete, yet to his eyes the work remained unfinished.

One day I remember Borda waiting in anticipation. When Nanda-da arrived, he came over to me and asked me to prepare thick blends of indigo and Chinese ink separately. As I was mixing the colours, I recall Nanda-da gazing intently at Borda’s painting. He then moistened a thick flat brush and dampened some parts of the canvas. With another flat brush barely dipped in the thick dual hues, he swiftly applied some strokes on the riverbank and seamlessly moved his brush over the body of water and the outstretched sky. It was as if a slice of life was unravelling before our eyes— in that very moment one could almost hear the dark evening waves lapping rhythmically against the silent ghat. Borda’s face broke into a delighted smile, and Nanda-da put down the brush.

|

Nandalal Bose, Untitled, Watercolour on card, 5.7 x 3.7 in., 1948. Collection: DAG |

During these painting sessions, Borda Nanda-da Jamini-da would often have deep discussions on art. Nanda-da would joke about Jamini-da’s obsession with pat. At times, Jamini-da would spread out a fresh sheet of paper, and perhaps step outside for a bit before resuming to paint. During this brief interlude Nanda-da would quickly paint something in the style of patachitra on the sheet and move back to his spot. On returning Jamini-da would initially be taken by complete surprise, but when he pieced together what had happened in his absence he would simply smile. After carefully setting Nanda-da’s pat aside, he would begin working.

These paintings of Jamini-da would later constitute the bulk of the works [following the new artistic course] shown at his first major exhibition at the [Government] Art School. It was mostly organised by Borda [during September-October, 1929]. This was the sort of work he loved doing and would execute with the utmost skill and expertise. I particularly recall a day after the exhibition: Jamini-da was sitting in his segment of the west-facing atelier, Borda walked in and in a triumphant gesture showered Jamini-da with a bundle of notes. But let this be— this is a story for another time.

Translated by Ayana Bhattacharya

Rani Dey, Untitled, Woodcut on newsprint paper, 8.5 x 6.0 in., 1938. Collection: DAG