Play Fair: Exploring the Museum as a space for playSumona Chakravarty April 01, 2024 At Play Fair you step into artworks, experiment with the ways you look at them, embody them, and sometimes even make your own. It is a carnival of games based on art from the DAG collection that has travelled to the grand courtyard of the Indian Museum and the gardens of the Victoria Memorial Hall, setting off encounters with artworks in unusual formats—from human-scale board games and installations, to card games, charades, quiz contests and role plays. Now three editions old, Play Fair is a temporary, carnivalesque manifestation of what a museum can be, and makes a strong case for reimagining the ways in which people explore art and historical artefacts in museums. |

|

Leisure and Play On any given day when you enter the Indian Museum you are welcomed into the sprawling green lawns of the inner courtyard with families, friends and lovers, of all ages and from diverse places, spread out across the grass. The gardens of the Victoria Memorial, famously designed by Lord Redesdale and David Prain of the Calcutta, and later, Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew, are also vital to its iconic status, and see many more visitors a year than the galleries. During our collaborative exhibition with the Indian Museum, titled ‘March to Freedom’, we experimented with the space within the galleries, with the help of interactive tables, games and writing cues to engage adults and children alike. But we also wondered how to engage and involve the various people who visit the lawns and gardens of these institutional spaces for leisure and relaxation, without burdening them with pedagogic discourse. |

|

|

Play Fair at the Indian Museum

A muder mystery role play at the first Play Fair

Here, outside the stately galleries, the audience would meet the objects on their own terms, making them a part of their shared public space, instead of observing them at a safe, and sometimes daunting, distance. We hoped that in the freedom and openness of the lawns and gardens, audiences might be encouraged to give time and effort to explore our collections through play, in exchange for stories, memories, ideas, and prizes (surely the prizes would work!). During the first few minutes of the very first Play Fair at the Indian Museum in March 2023, we anxiously wondered if we had in any way managed to break the barriers between museum objects and their viewers. We had set up ten different activity stations featuring varying props and large-scale installations in the central courtyard, which made the whole setup resemble a dramatically charged stage before a play was about to begin—with audiences in the surrounding corridors looking at the spectacle from a distance. |

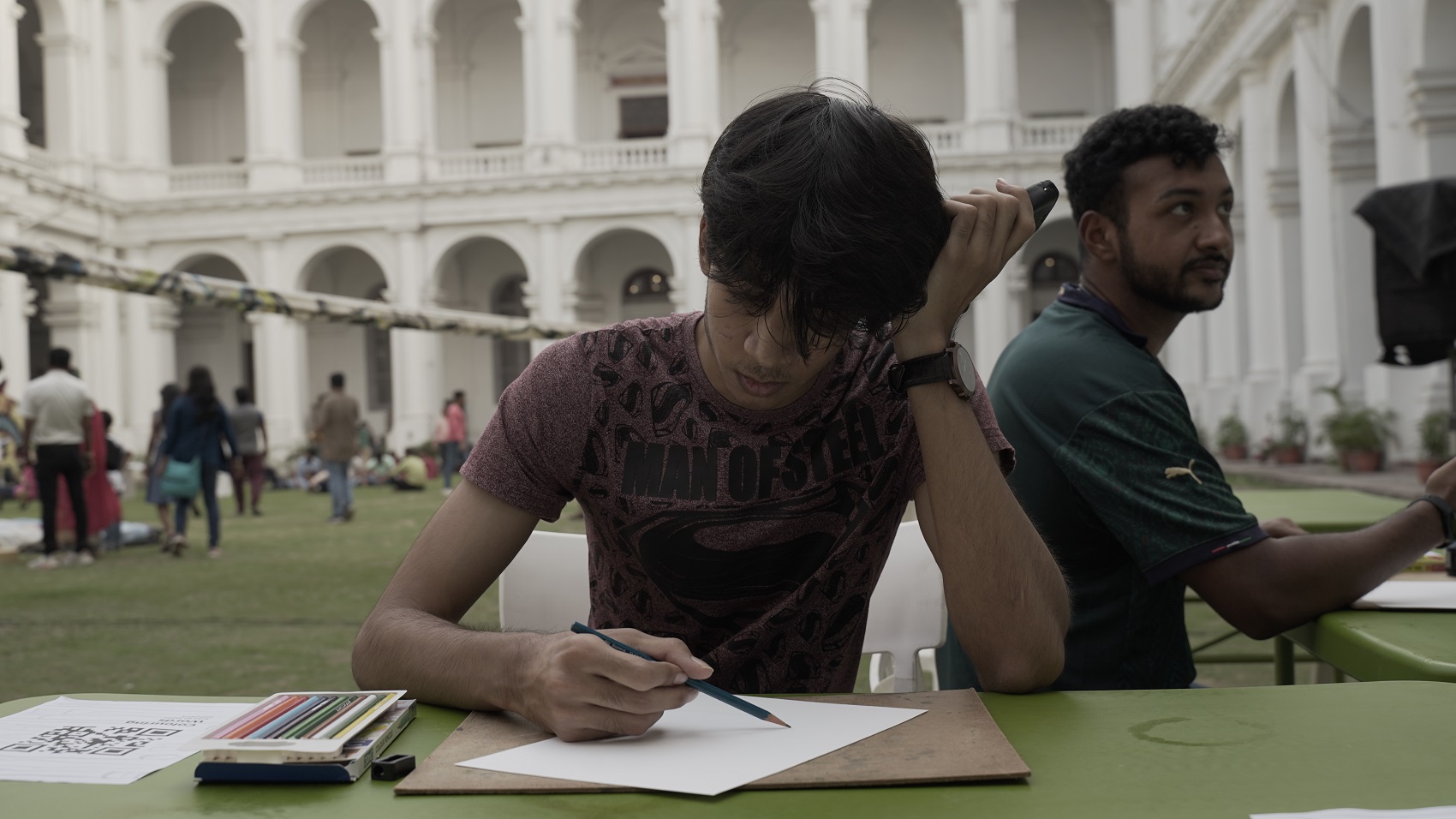

Encounters with artworks in unusual formats at each activity station

Encounters with artworks in unusual formats at each activity station

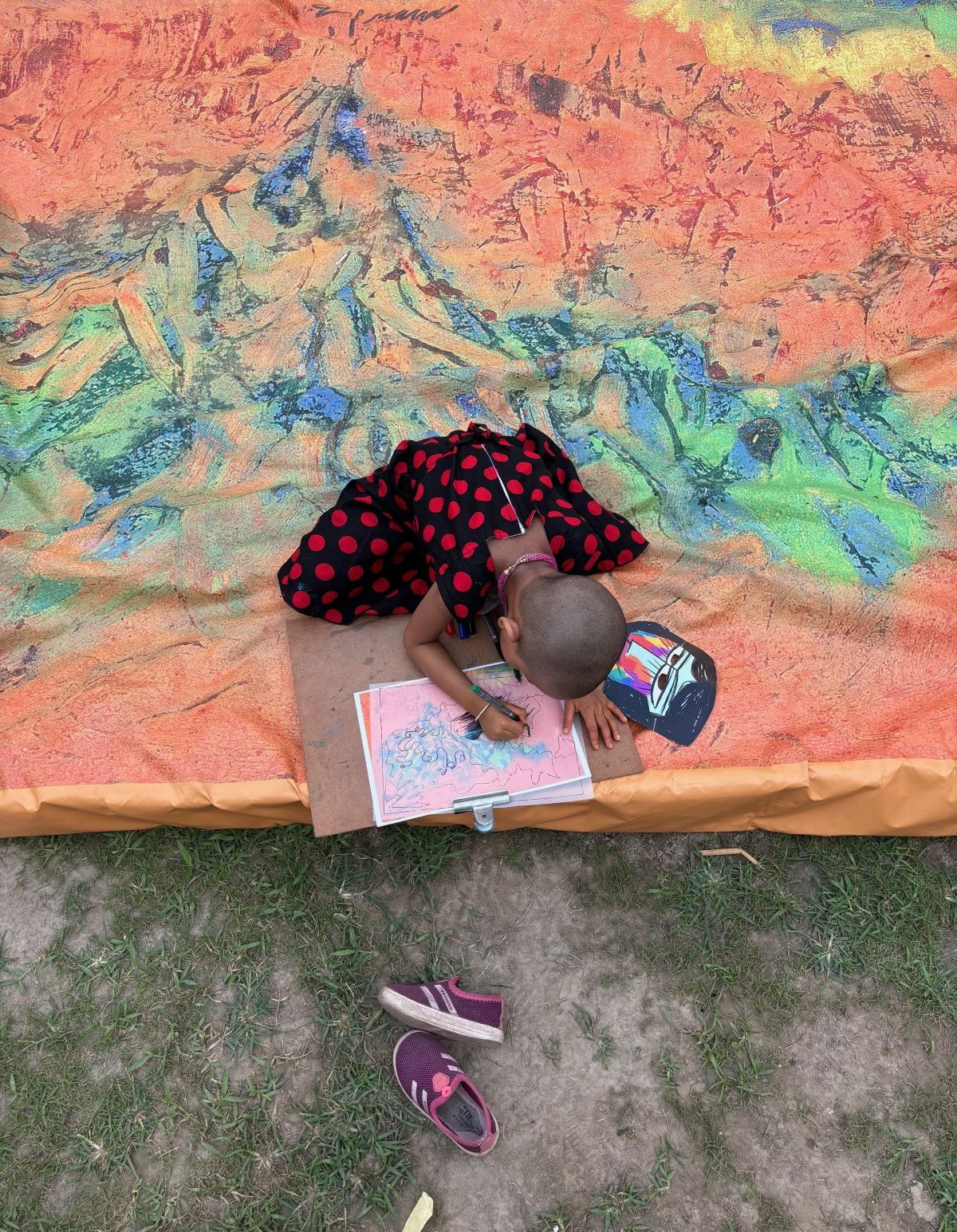

Encounters with artworks in unusual formats at each activity station

With every second of hesitation, we wondered if we may have gone a step too far and alienated our audience, who perhaps preferred a lazy afternoon at the museum, without the prospect of ‘participation’, ‘engagement’ and other loaded propositions under the guise of play! It took one curious and brave child, who dragged their parents along with them, to get the games started—people streamed in, walked around curiously, got into the act, and took over the space. Some games generated an energetic rivalry between friends, others got strangers together in a silent communion as they made art together. |

|

The following year, at the Victoria Memorial Hall’s (VMH) museum gardens, Play Fair went from the theatrical stage of the Indian Museum to a no-holds-barred mela (carnival), with large crowds gathering to play as well as watch the games. The insertion of a place of play within the space of leisure, opens up the possibility of a collective experience of looking at objects and collections, the expert voice of a museum text or guide is replaced by a game facilitator who is fellow explorer and jester; and the take aways for each visitor is unique as the game play, and ensuing chatter takes different twists and turns. |

|

|

|

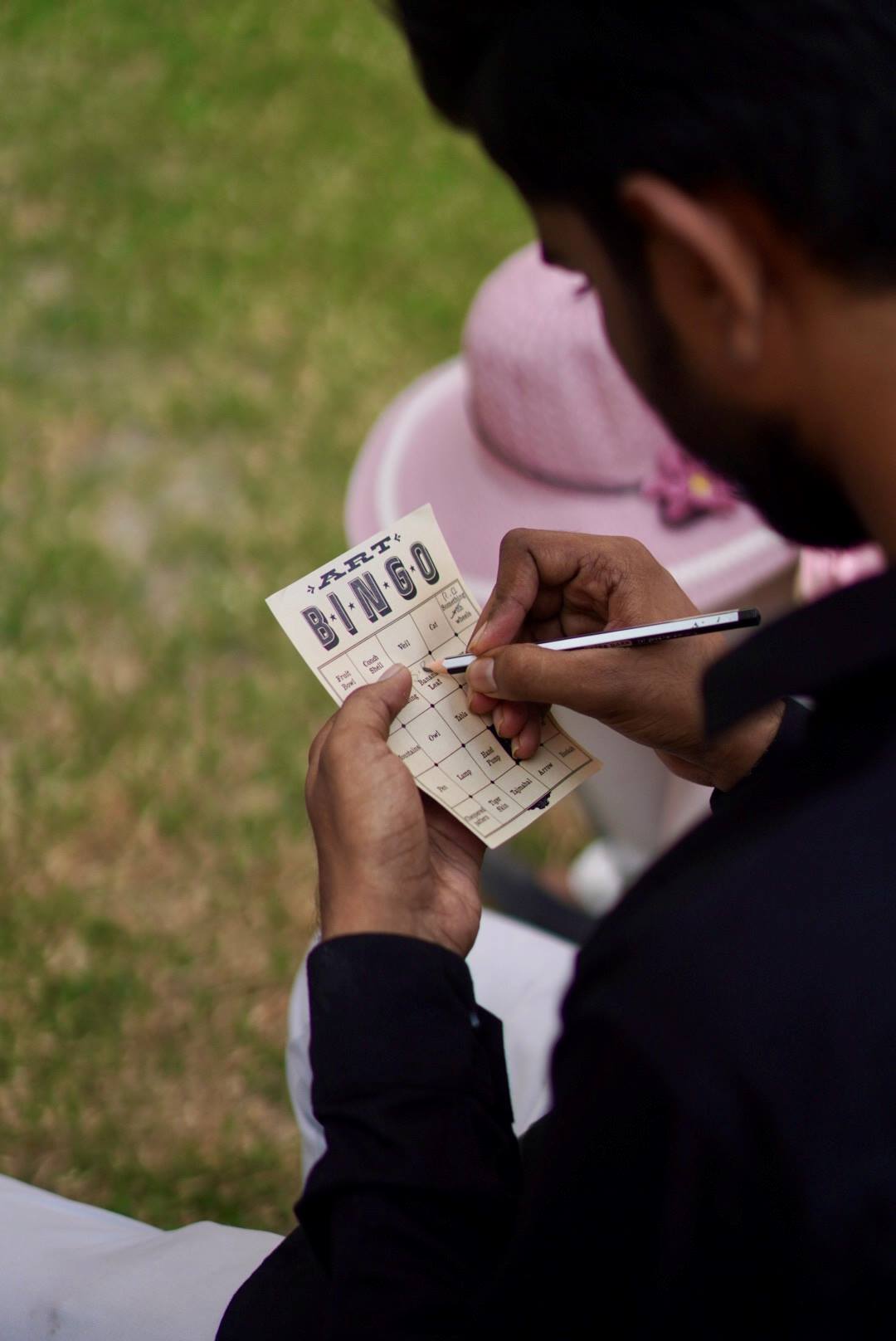

Seeing Playfully The first game people are usually drawn to features a towering 8 feet cutout of the ‘Kalighat cat’. It’s a simple and approachable game—where you pin a prawn on the image of the beral tapashwi (ascetic cat), as you would tail the donkey in the more familiar format. For us it is a device to draw attention to the symbol of the prawn in popular Kalighat pats to reveal how it represents the greed of the religious elite. Another game that focuses on details within images is Art Bingo where players compete to complete their bingo cards by identifying minute elements of the artworks. Each artwork is projected for fifteen seconds, extending the time afforded by a brisk walk through the museum gallery, and almost uncomfortably long compared to pace of scrolling through our phones. Both these games are premised on the idea that looking closely at details in an artwork helps us find a hook or a connection that sparks our curiosity about the image and trains our focused attention as it sets the process of observation and interpretation into motion. |

|

|

Creating paintings based on audio descriptions of artworks

Seeking out the lost travellers in a landscape by Nandalal Bose through a board game

Spotting artwork details at Art Bingo

Pin the Prawn

Through Play Fair we try to set the atmosphere, be it that of a stage or a mela, to make museum objects approachable, but our hope is that our games will encourage people to join us in our experiments with the process of seeing art—sometimes blindfolded, sometimes in 15 second bursts, and always fearlessly. The games prompt audiences to trust their intuition, and to enjoy the process of finding new vantage points for observation. Another example is Colouring Words where audiences listen to descriptions of works from our collection, then draw them from their imagination, and finally see the featured artwork at the very end. The final ‘reveal’ works like a charm each time as their experience of seeing the work is heightened in juxtaposition with the images, textures, techniques and memories they have conjured through their own artworks. |

|

Confusion and clarity The second edition at the VMH and the third at the Indian Museum in early 2024, gave us the opportunity to refine our methods. Making art approachable and encouraging close looking was a rewarding outcome so far, but we wanted to take the interaction with the artworks and fellow visitors one step further. For this we needed the games to generate a back-and-forth process—a dialogue, in other words, rather than a fleeting interaction or didactic lecture—where audiences work through a question or an idea, step outside their comfort zones to find new ground, and ask fresh questions about art in their everyday life. It’s a work in progress, perhaps without a finish line, but there have been moments this year that took us close to this ideal state of play. |

|

|

Exploring Nandalal Bose's scrap paper doodles

Exploring Nandalal Bose's scrap paper doodles

Exploring Nandalal Bose's scrap paper doodles

Play allows for structure and freedom simultaneously, it creates a safe space with rules and boundaries that leaves room for uncertainty, discomfort, and ultimately experimentation. At VMH a large reflective surface we had installed became a popular Instagrammable backdrop that drew a large and curious crowd. The mirrored surface displayed Nandalal Bose’s unique scrap paper works, where the artist fashioned curious creatures out of torn pieces of paper. Visitors were asked to try their hand at Nandalal’s paper-tearing exercise, roughly pulling some paper apart and then trying to imagine what forms emerge from the haphazard shape. Visitors were quick to resort to making familiar shapes—fish, huts, boats—but when challenged to let go of a predetermined outcome and trust the process, their initial spontaneous attraction to the game gave way to hesitation. Some moved to an easier game, others watched and began to get comfortable with this unusual experiment. Soon the board was full of scrap paper doodles inspired by Nandalal. |

Cartoon Headsup in play

Exploring details of Gaganendranath Tagore's caricatures through Cartoon Headsup

Cartoon Headsup

Another game that encouraged players to step outside their comfort zone was ‘Cartoon Headsup’ where teams had to enact and make sense of characters and objects in caricatures by Gaganedranath Tagore and Chittaprosad. Those baffled enough by the absurd, exaggerated images, lingered to talk about the artworks and their powerful social satire. These ephemeral moments of confusion and clarity, where audiences accepted our invitation to work through a process of discovery with us, makes a strong case for play within museums, bringing audiences into dialogue with museum objects. |

|

Play Fair also invites audiences to try another unfamiliar experience—interacting with fellow museum-goers. We see this at the Colouring Words art table as people draw together, at the Art Shuffle card game as strangers get together for a game that involves collective decision making, or even at the ‘Lost Travellers’ board game, where they literally step into a Nandalal Bose postcard and move strategically across the tiles of the board to reveal the hidden figures in the painting. Play generates this proximity, and sometimes leads to brief yet surprising moments of exchange, where the museum lives up to its claim of creating a vibrant public space. |

|

|

|

Through games both spectacular and intimate, Play Fair transforms a space of leisure into a space for new encounters, fresh experiences and questions. As it moves nomadically from one museum to the next, these experiments open up new methods and approaches for transforming museums from their traditional institutional roles into places that encourage the freedom of engagement and curiosity. With this, Play Fair lives on beyond its annual appearance, becoming a proposition for how museums, their collections and their publics come together. DAG would like to thank Shri. Arijit Dutta Choudhury, Dr. Sayan Bhattacharya and their team at the Indian Museum and Dr. Samarendra Kumar and his team at Victoria Memorial Hall for their collaboration. |

|

|