New Horizons: The Aesthetics of Statecraft

New Horizons: The Aesthetics of Statecraft

New Horizons: The Aesthetics of Statecraft

collection stories

New Horizons: The Aesthetics of StatecraftShreeja Sen In 1911, when King George V, announced the shifting of the capital from Calcutta to Delhi at his Durbar, he set in motion the evolving discourses that would shape the canons of the nation’s modern aesthetic identity well beyond the end of the Empire. An entirely new city was to be built, suitable for the seat of power in the crown jewel of the Raj. But this ambitious project raised a crucial question: in what architectural style should it be built? What aesthetic vision would best embody the spirit and authority of the British Raj in its new capital? |

Asit Kumar Haldar

|

The announcement was followed by passionate debates regarding the matter, and we know that, eventually, it was decided that Edwin Landseer Lutyens would be given this mammoth and controversial task, along with Herbert Baker. To fully understand the context in which these two figures had to work, and within which the design and aesthetics of what would eventually become the Rashtrapati Bhavan in 1950, one must first step back to the century prior to these debates. |

|

|

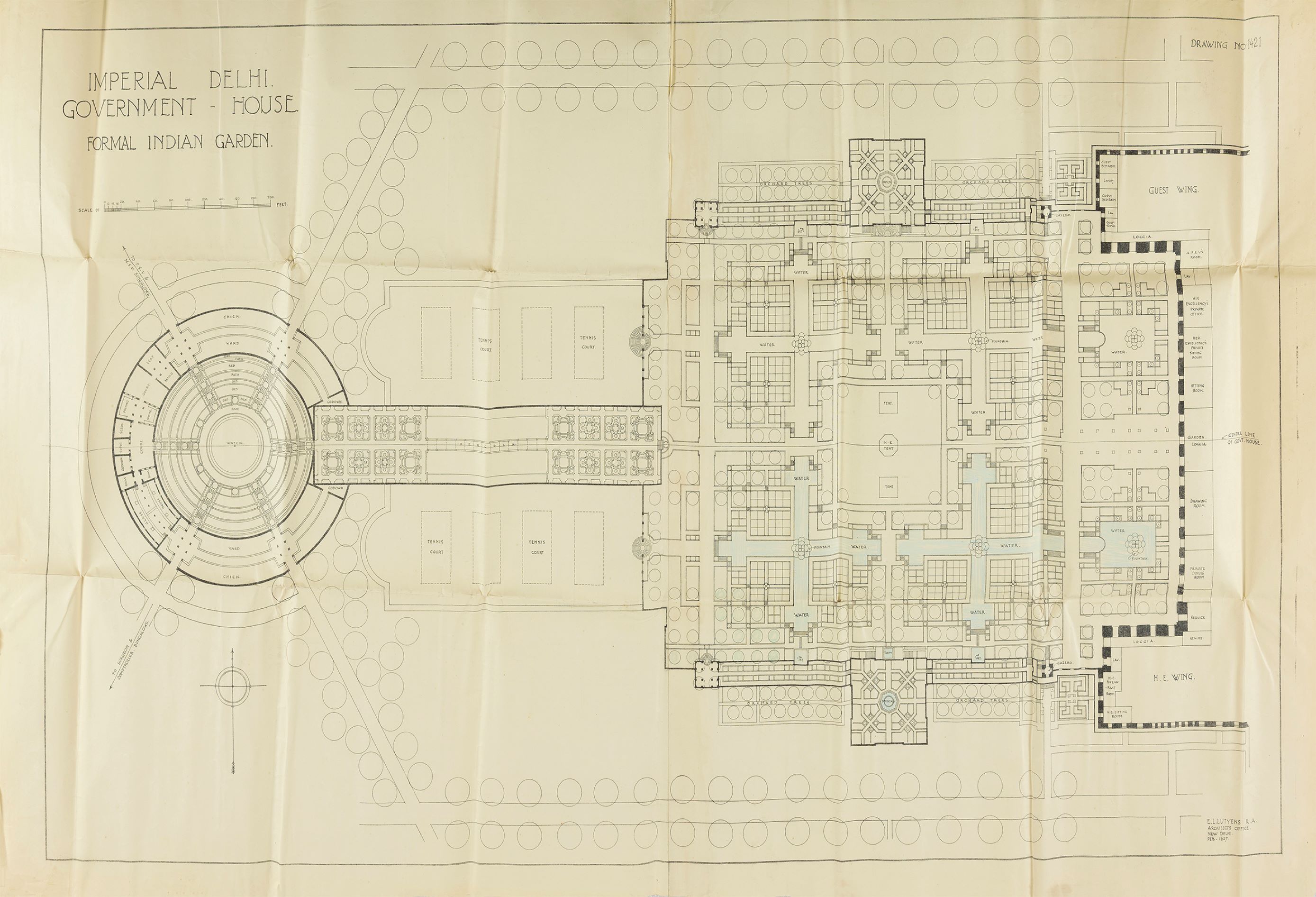

Edwin Landseer Lutyens

Imperial Delhi. Government - House, Formal Indian Garden

1927, Ink and graphite on paper

Collection: DAG Archive

Unidentified Publisher

Rashtrapati Bhavan, from a Set of 18 Magic Lantern Slides (Views of Delhi)

early 20th century, Photographic images on glass slides

Collection: DAG Archives

Partha Mitter, in his introduction to the book, The Arts and Interiors of Rashtrapati Bhavan: Lutyens and Beyond, traces the context all the way back to the debates regarding the colonial administration’s approach to the governance of Indians, in the early nineteenth century; between those that championed notions of European progress versus those who believed in preserving time-honoured traditions of the East, which were exemplified in the views of Thomas Macaulay and William Jones respectively, in matters of education. These debates had far-reaching implications in the architecture of colonial India, which Lutyens had to contend with even after a century. The latter half of the nineteenth century, particularly following the suppression of the 1857 revolts, witnessed the projection of the British Raj’s political ambitions onto architectural forms. Art and architectural historian James Fergusson’s disdain towards ‘Hindu’ architecture, which he characterised as florid, and appreciation for the ‘scientific’ nature of Islamic architectural elements of the dome and the ‘true’ arch, championed a style which he called Indo-Saracenic. Embedded within the popularity of this style was a colonial conviction: that only the ‘civilised’ and ‘enlightened’ West could successfully achieve such a synthesis: something believed to be beyond the reach of Indians, who were seen as perpetually divided by communal tensions. |

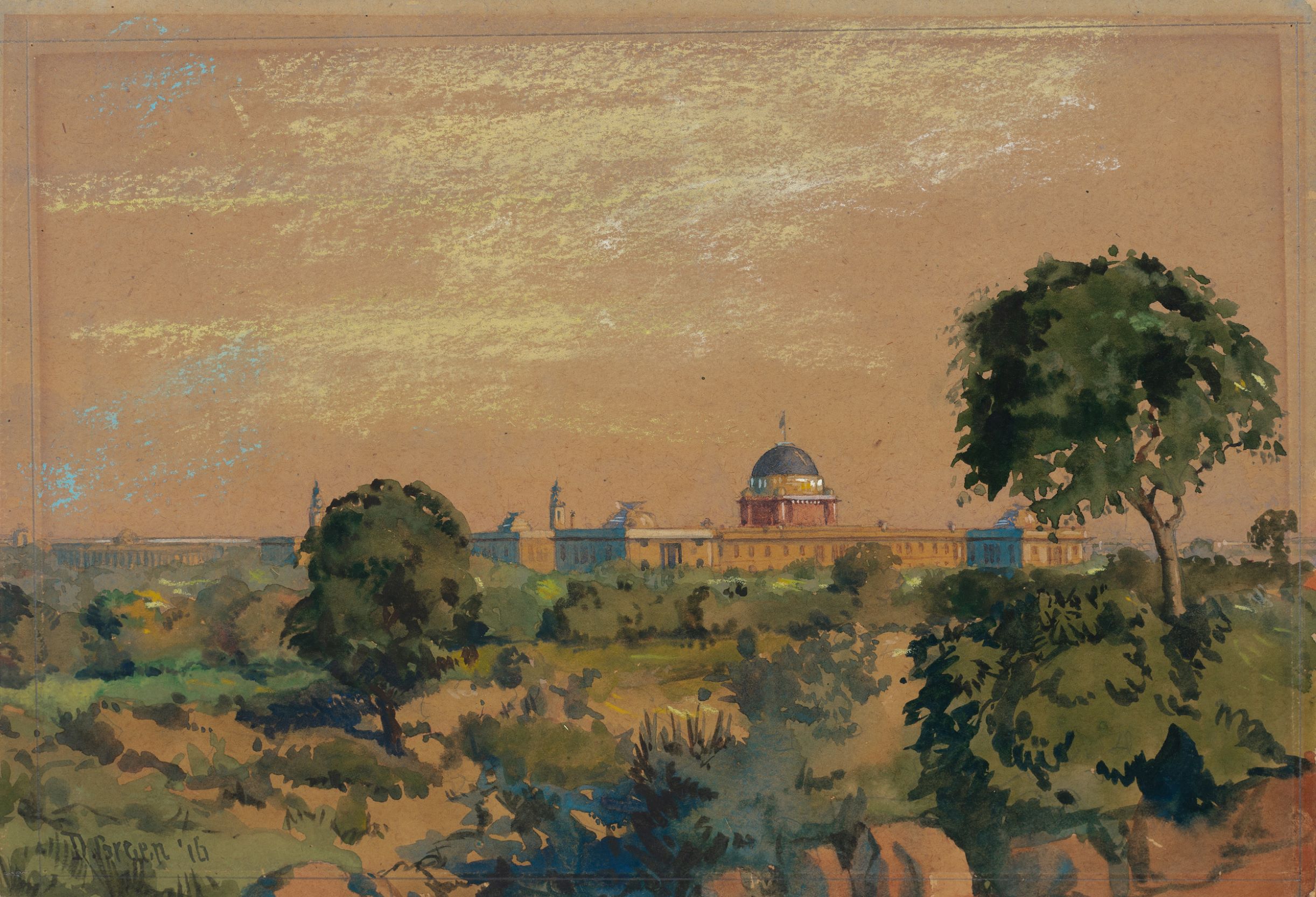

David Gould Green

View of Viceroy's House (now Rashtrapati Bhavan)

1916, Watercolour and pastel on cardboard

Collection: DAG

The early-twentieth century, however, saw impassioned supporters of indigenisation of art and architecture, parallel to the popularity of the Arts and Crafts movement in Britain. Perhaps the most outspoken in his support of Indian artisans and applied arts was Sir George Birdwood, curator at the V&A in London and later the Victoria and Albert Museum in Bombay (now the Bhau Daji Lad Museum). It is within this atmosphere of debate that one must understand Lutyens’s decisions in designing the new capital of the Raj. His appointment itself was contentious, raising the key question of how Indian the new seat of power ought to appear. While some supported a classical, grand, and imperial style, others, such as Birdwood and E. B. Havell, the influential head of the Madras School of Art and mentor to Abanindranath Tagore, argued for a distinctly Indian architecture, built by Indian hands. The final decision, shaped by Viceroy Lord Hardinge, reflected an uneasy compromise: although sympathetic to the pro-Indian position, Hardinge ultimately considered a classical aesthetic essential, and thus entrusted the task to Sir Edwin Landseer Lutyens, who was asked to incorporate indigenous elements into his designs. |

|

Lutyens' claim to this crucial job arose from his experience of designing key markers of the Empire such as the British embassy in Washington and the British pavilion at the 1900 Paris Exhibition and the 1911 International Exhibition in Rome. However, to read Lutyens’ design of New Delhi, through the lens of the ‘Britishness’ evident in past oeuvre, would be reductive and unjust to the ultimately layered approach he employed. While he remained largely unmoved by the passionate advocacy of the proponents of Indian art like Havell and Birdwood, he also rejected what he called the ‘sterile stability’ of the classical English style. In toeing this incredibly delicate balance, his approach was led by a desire to birth a new modern style which was not a thoughtless amalgamation of either style but rather a radical modernism born out of a deep sensitivity to the function of form, whether Indian or European, and their dynamic interplay. |

|

|

Lal Chand & Sons, Delhi

Viceroy’s House, New Delhi

Collotype, divided back, early 20th century

Collection: DAG Archive

The Rashtrapati Bhavan’s design, therefore, while employing the unmistakable vocabulary of Palladian classicism, is adorned by Indian ornament and elements everywhere—the temple bells around the otherwise classical pillars, the chajjas, or the jalis, or the imposing dome that would recall to any citizen of India the stupa of Sanchi. The art within the Rashtrapati Bhavan complex, deserves as nuanced a reading as the design of the complex itself. Unlike the murals which adorn the Rashtrapati Bhavan, the paintings which hang from its walls are not part of the material fabric of the structures and yet form a crucial layer of its cultural and political fabric. While the collection of paintings and their placement have been in constant flux over the decades, the decisions to include or remove works, are symptomatic of the concerns that framed the canons of Indian modern art. |

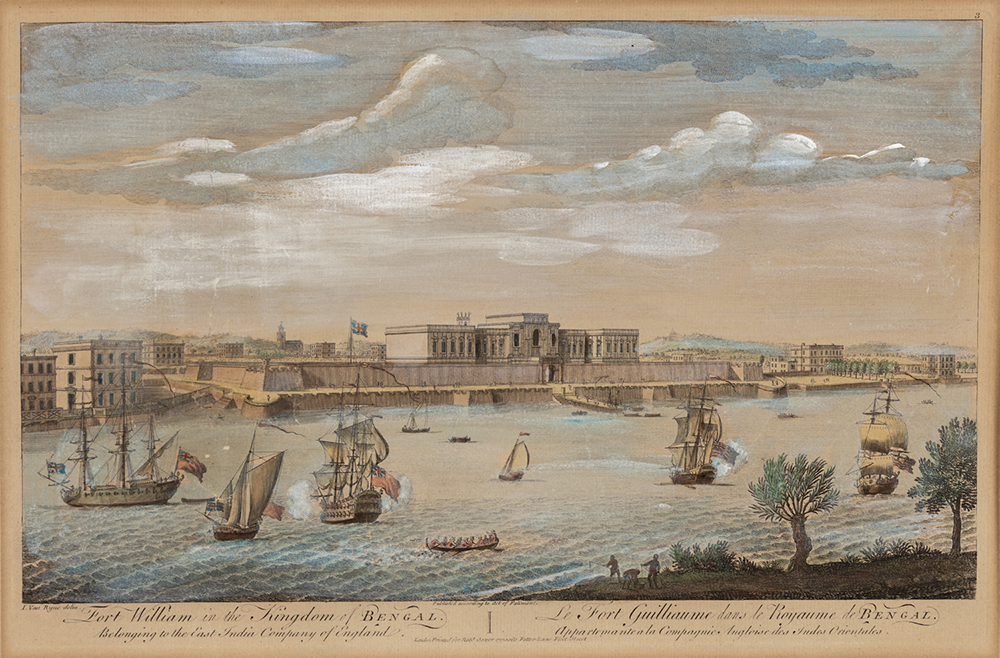

Jan Van Ryne

Fort William in the Kingdom of Bengal

Engraving tinted with watercolour on paper

Collection: DAG

Oliver Hall

A Border Castle

c.1921, Drypoint on cream laid paper

Collection: DAG

Lutyens’ vision for the aesthetics of the house emerges in the paintings which were specifically designed for certain spaces in the house. For instance, the Long Drawing Room, has two fireplaces facing each other above which hang two large landscape paintings. Both were painted by English artist Oliver Hall based on engravings by the eighteenth-century Dutch artist Jan Van Ryne, depicting Fort St. George in Madras and Fort William in Calcutta. The choice of the two fort settlements harks back to the early colonial past and creates an acknowledgement of the link between the some of the earliest colonial edifices and the newly built Viceroy’s house. In the paintings, Hall chooses to highlight the imposing built-forms and neglects Van Ryne’s focus on the river and sea vessel activity in the landscape—perhaps as a nod to the majesty of the building which houses them. Lutyens had niches built specifically for these works; so their form and placement, when read in conversation with his overall architectural choices, foreground a lexicon of the aesthetics of diplomacy he constructed. |

|

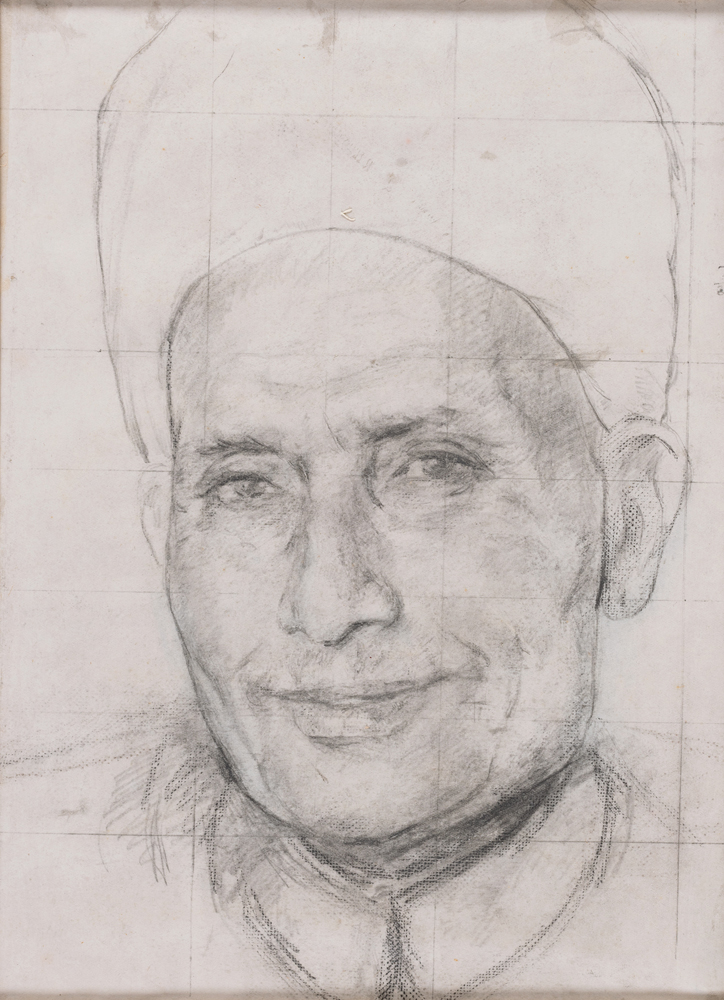

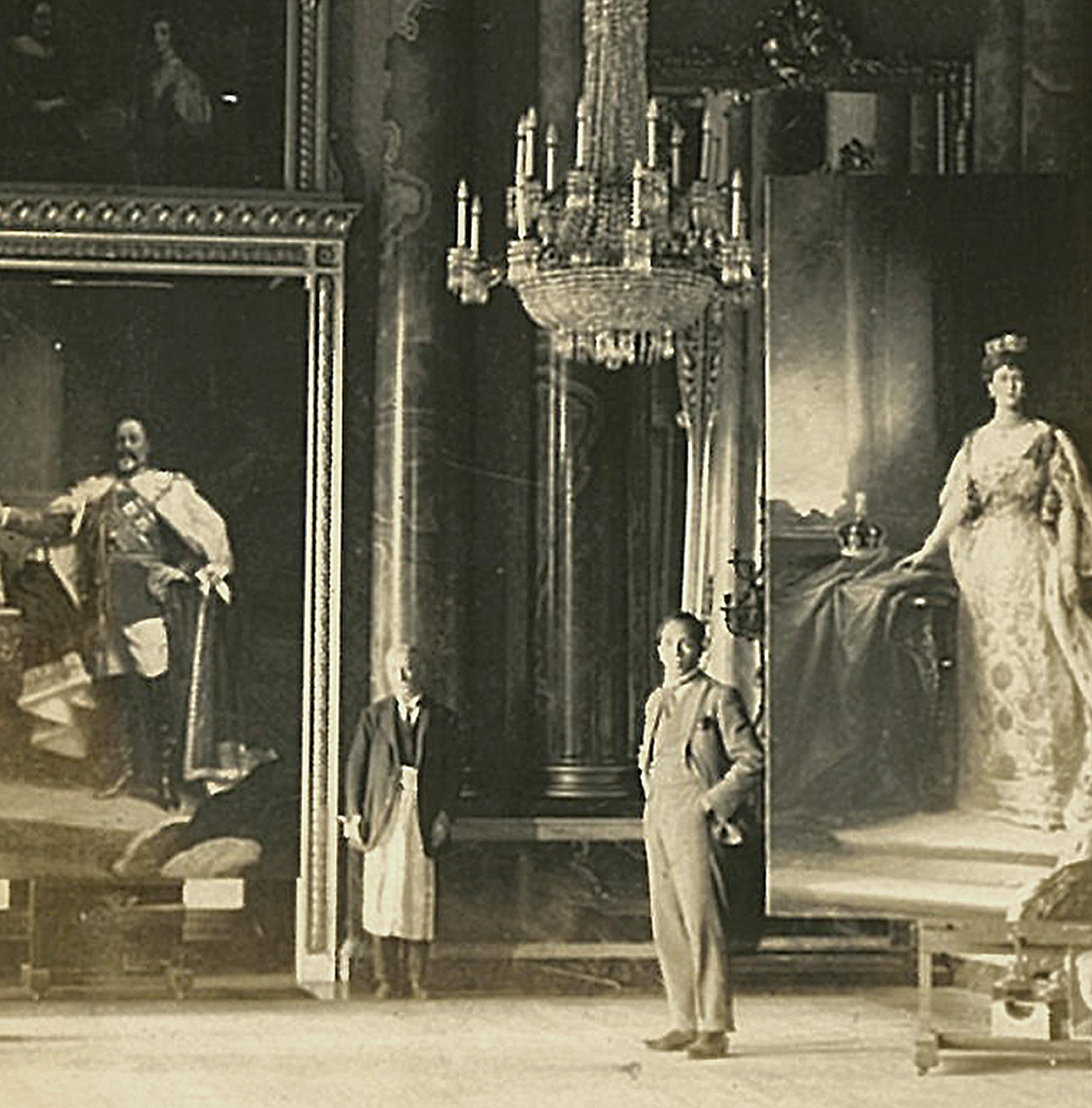

This beacon of diplomatic design also necessarily required the essential royal and aristocratic portraitures, without which any viceregal residence was incomplete. For the imperial portraits, Lutyens staged a competition for two Indian artists to travel to London and make copies. Atul Bose and J. A. Lalkala were subsequently chosen and copied portraits from both Windsor Castle and Buckingham Palace. This entrustment of the copies to two Indian artists, rather than employing artists already in London—which would also have been more economical—displayed a commitment to the involvement of Indian artists and artisans in the arts of the Viceroy’s House. |

|

|

Atul Bose

Untitled (Portrait of J. K. Birla)

c. 1955-60, Graphite on paper

Collection: DAG

J. A. Lalkaka

Bai Pirojbai Ardeshir Jemshetji Lalkaka

1942, Oil on canvas

Collection: DAG

Atul Bose At the Royal Academy in London, 1922

Image courtesy: Wikimedia Commons

However, the art at the Rashtrapati Bhavan, brings forth more than just the sensibilities of Lutyens, and the debates led by Havell, Birdwood, W. E. Gladstone Solomon (who was the Principal at Bombay's J. J. School of Art) and others regarding Indian art and the schools within. Even during colonial rule, Lutyens’ grand design was intervened in, and perhaps even interrupted, by the inhabitants, of what was after all a residence. The most famous example of this perhaps, is Lady Irwin’s redecoration of the ballroom in 1929, now known as the Ashoka Mandap, where she introduced tinted black mirrors and Lady Willingdon’s installation of a Qajar dynasty painting to the ceiling. The central painting, dated c. 1820, was done in oils on canvas by an unidentified Persian artist, commissioned by the Qajar monarch Fath ‘Ali Shah, offered to George IV of England. Lord Irwin arranged for it to be transported from the India House in London, and once it was installed by the Willingdons on the ceiling, Italian artist Tomasso Colonello was commissioned to paint the surrounding area around the Qajar work’s centerpiece. |

|

The Rashtrapati Bhavan became the official residence of the President of India from 1950 onwards, and a number of new embellishment projects were undertaken. Of these, of particular note are the murals in the State Corridor by Sukumar Bose. Bose was one of the four Indian painters who worked on decorating the India House in London built by Herbert Baker. He was trained under Asit Kumar Haldar, a stalwart from the Bengal School who was taught by Abanindranath Tagore. And so, while the Secretariat blocks are adorned by Bombay school artists, their Bengal school counterparts found presence in Rashtrapati Bhavan through the works of Bose. Bose was instructed in the themes of the murals by Haldar himself, who was deeply inspired by the frescoes at Ajanta. The resulting mural which even today watches over crucial diplomatic exchanges, displays figural and floral elements inspired by the Indus Valley Civilisation, the Ramayana and Mahabharata, interwoven with Persian calligraphy, Quranic ayats, Buddhist and Hindu designs, and even forms from Bengali alpona. One of the most striking features is his use of shlokas from the Bhagvad Gita, executed in gold paint. |

|

|

K. S. Kulkarni

Untitled (Jawaharlal Nehru)

48.0 x 36.0 in.

Collection: DAG

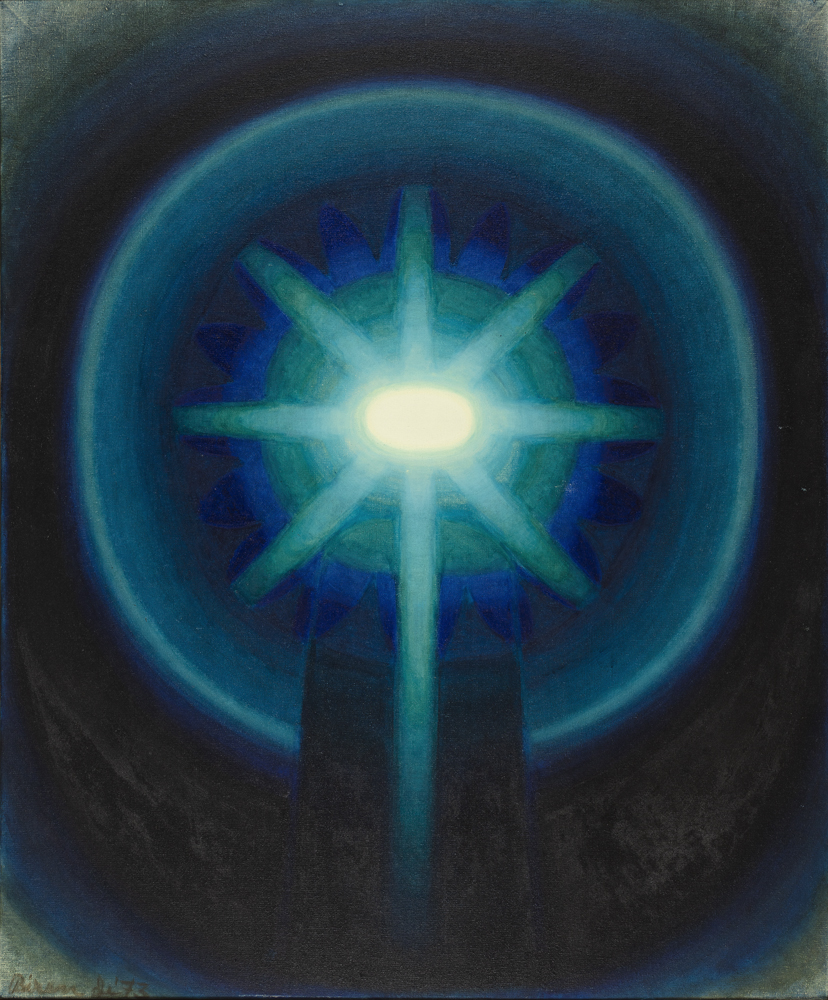

G. R. Santosh

Untitled

1988, Oil on canvas, 30.0 x 24.0 in.

Collection: DAG

Atul Bose also served as the first curator of the paintings at the residence in 1945. With independence, the art collection also underwent radical shifts, with imperial and aristocratic portraits being moved and newer commissions taking their place. Notably, Bose also painted the portrait Dr Rajendra Prasad, India’s first president—a fitting nod towards a continuing tradition of portraiture adapted to suit the new democratic nation. Other modern artists, such as K. S. Kulkarni from the Bombay, G. R. Santosh, and Biren De, were also commissioned to paint portraits while B. C. Sanyal was commissioned for sculptural portraits. Kulkarni’s oeuvre is filled with abstracted figural forms like Sanyal’s, while both Santosh and De were part of the neo-tantric movement—strands of modernist practice that were seen as new horizons for the canons of Indian art. |

Biren De

September 73 (a)

Oil on canvas, 42.0 x 35.0 in.

Collection: DAG

B. C. Sanyal

Shrouded Woman

1961, Cement and stone, 16.7 x 18.0 x 10.5 in.

Collection: DAG

The choice of these artists for the presidential portraits, reflects a thoroughly modern attitude, although it is worth noting that these artists were not without institutional affiliations. Both Sukumar Bose and Sanyal were founding members of the All India Fine Arts and Crafts Society, which set the foundations for the establishment of the Lalit Kala Akademi by the Indian government in support of the visual arts in 1954. Sanyal later served as the Akademi’s Secretary while Kulkarni went onto serve as its President. |

|

Under Sukumar Bose’s curatorship and later Jogen Choudhury’s, the Rashtrapati Bhavan also amassed a large collection of modernist paintings by Jamini Roy, Benode Behari Mukherjee, Rameshwar Broota and others. Through the artists it chose to commission and patronise, the Rashtrapati Bhavan continued to be a pivotal contributor to the story of Indian modern art. |

|

|