|

DAG Recommends Modernists in the CityscapeShreeja Sen December 01, 2023 In a newly independent India, Nehru’s investment in architecture, urban planning and aesthetics was a postcolonial project to promote India as a sovereign and modern nation state. The literal and figurative task of building the nation posed new questions regarding whether there was a need for a ‘national architecture’ which would be shaped by the center and embody the culture and position of the modern state. Many argued for this endeavour, fashioned after the nationalist architecture of the U. S. S. R. and China, where identifiably ‘Indian’ elements would contribute to a visual identity in built environments. Others preferred what historians have termed as a ‘revivalist’ approach which looked to the rich heterogenous architectural traditions of the past, an approach not dissimilar to the Bengal School revivalism intellectually. |

|

Working within this cultural milieu of negotiating between the past and the future, the global and the regional, modern artists contributed to the discourse through their own creative interventions in the cityscape. While many modernists were invited by the government to actively shape and contribute to this modern urban aesthetic through commissioned works, others contributed through these debates and discourses finding expression in their practice. |

|

|

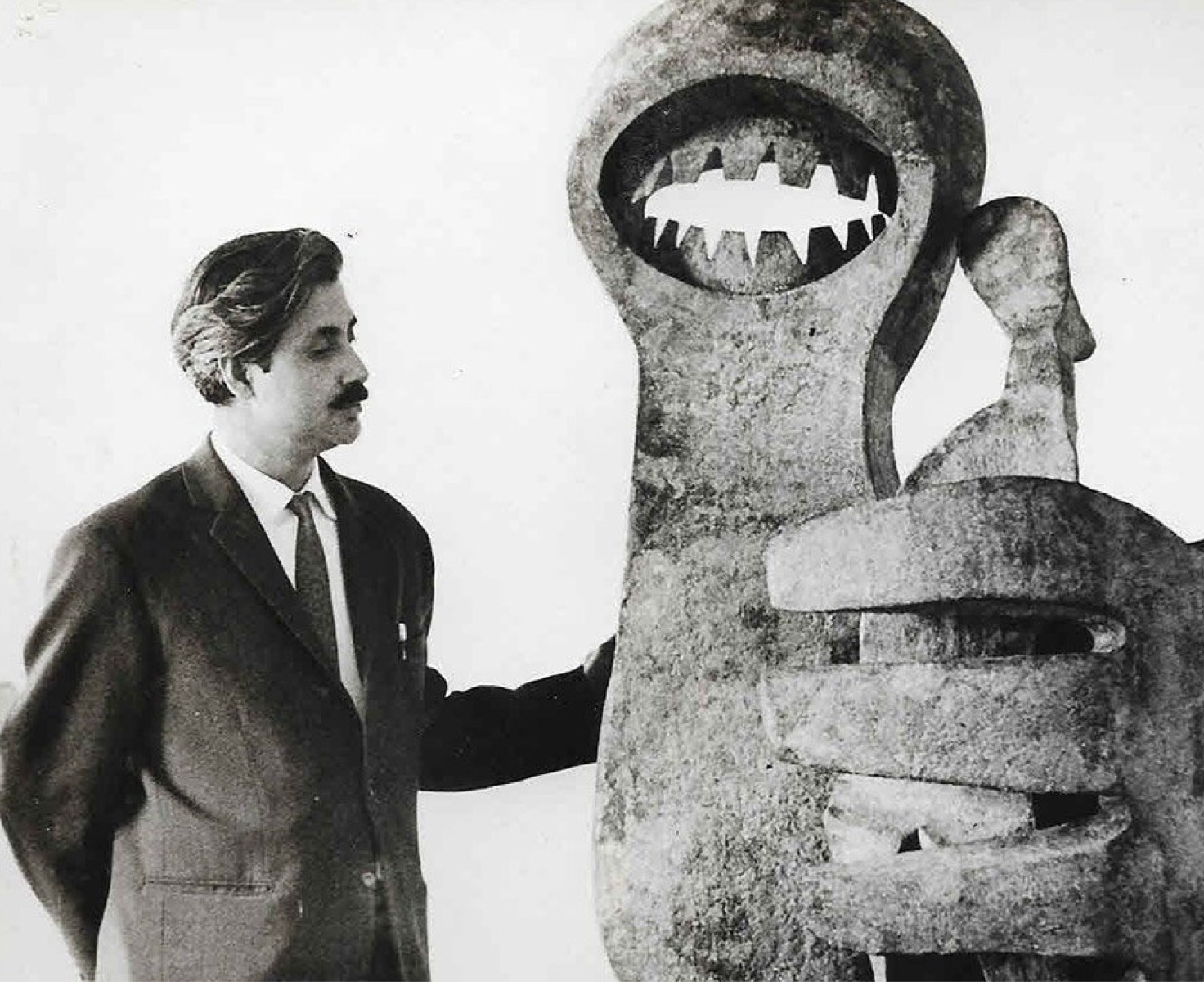

Amar Nath Sehgal

Bronze mural, Vigyan Bhawan, New Delhi

Image courtesy: Amar Nath Sehgal Private Collection, New Delhi

Amar Nath Sehgal

The Dragon

Collection: DAG

Amar Nath SehgalDesigned in 1955 to be the nation’s premier conference center, Vigyan Bhavan stands at the heart of Lutyen’s Delhi, exemplifying revivalist architecture in modern India. This type of architecture necessitates meaning being transmitted through ornamentation. In 1957, artist Amar Nath Sehgal, whose sculptures can be found in over twenty spaces across Delhi, was commissioned for the creation of a mural with this approach. He fashioned a relief mural using three tons of bronze, his ‘eternal medium’, projecting four inches out from the wall. The mural depicts rural, especially agrarian, life in India, which is an interesting formal choice for Vigyan Bhavan and its architecture. Aided by his training in industrial chemistry and physics, Sehgal’s material approach and technique is, as Mulk Raj Anand frames it, of a ‘futurist’. In 1979, the mural was removed without his consent during renovations. When despite his requests no action was taken, Sehgal filed for damages. After thirteen years of legal contention, the court ruled in his favour, in a landmark judgement in copyright law regarding moral rights of the artist. |

|

|

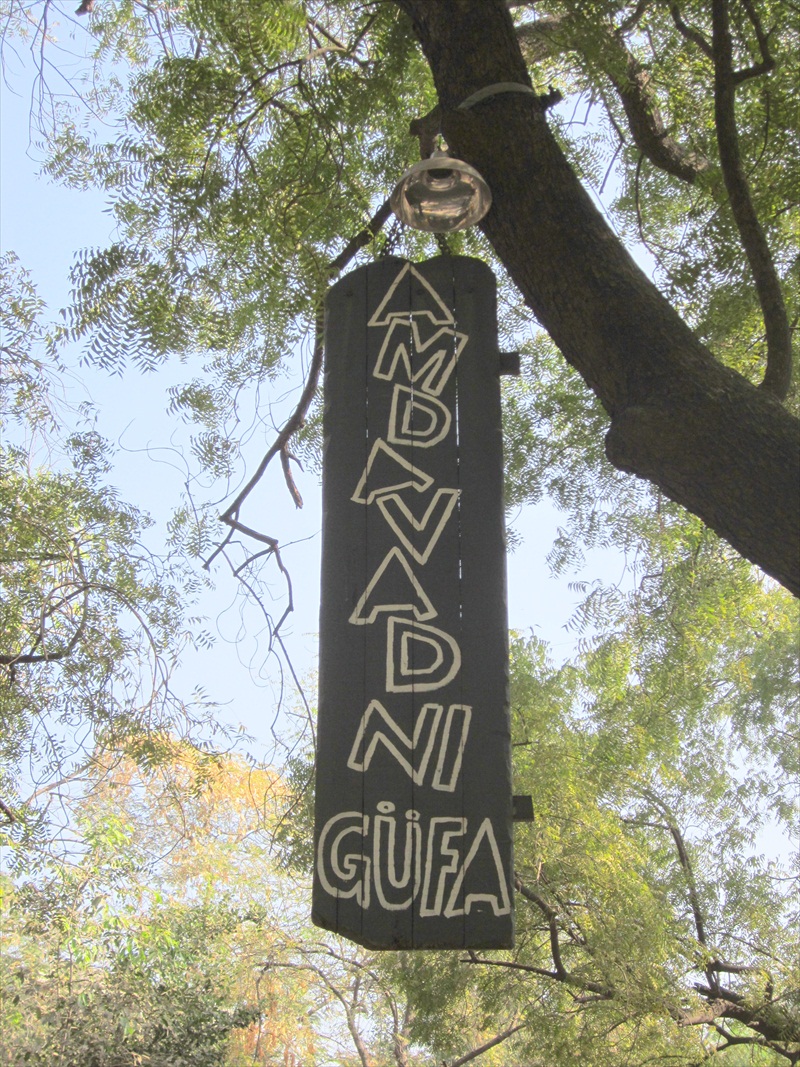

Amdavad ni Gufa

Image courtesy: Wikimedia Commons

Amdavad ni Gufa

Image courtesy: Wikimedia Commons

Amdavad ni Gufa

Image courtesy: Wikimedia Commons

M. F. Husain and B. V. DoshiA collaboration between M. F. Husain and architect B. V. Doshi, Amdavad-ni-Gufa was born out of Husain’s love for Ahmedabad and an urge to escape to the subterranean to avoid the heat; to which, Doshi brought his unique method of exploring the ‘modern’ in Indian architecture. Located on the campus of the Centre for Environmental Planning & Technology in Ahmedabad, Amdavad-ni-Gufa was designed as an art gallery of Husain’s work as well as a socio-cultural hub. Guided by computerised designs, the structure was built by Adivasis using their expertise in regional construction methods. Doshi has described this experience as a blurring of the distinctions between art, architecture, painting, and sculpture. Husain’s undulating black snake-line envelopes the exterior and his woodcuts placed within the caves play with light and shadow—a phenomenon he described as ‘still choreography’. The interiors are covered with works by him drawing influences from cave art and folk forms. Speaking to India Today, Husain had described the Gufa as signifying ‘the place man began and is thus a chapel to honour man and art’. |

|

|

The Belgian Embassy at New Delhi

Image courtesy: Massachusetts Institute of Technology and Peter Serenyi

The Belgian Embassy at New Delhi

Image courtesy: Massachusetts Institute of Technology and Peter Serenyi

The Belgian Embassy at New Delhi

Image courtesy: Massachusetts Institute of Technology and Peter Serenyi

Satish GujralAlthough not a trained architect, artist Satish Gujral’s award-winning design of the Belgian Embassy in Delhi is considered a rich case for the exploration of diplomacy through architecture and the modernist architecture of postcolonial India. The Embassy was constructed in the 1980s as part of building Chanakyapuri into a diplomatic zone begun by the Nehru administration. Built in exposed brick, following the principles of organic architecture, Gujral creatively navigates scale as a central skylight and windows allow ample light and depth while numerous arches provide a subtlety to the grandeur. Describing his approach to architecture, Gujral said in an interview with architect Romi Khosla, ‘Architecture is essentially a collage of memories, ideas, and things—combined they endow a building with presence’. |

|

|

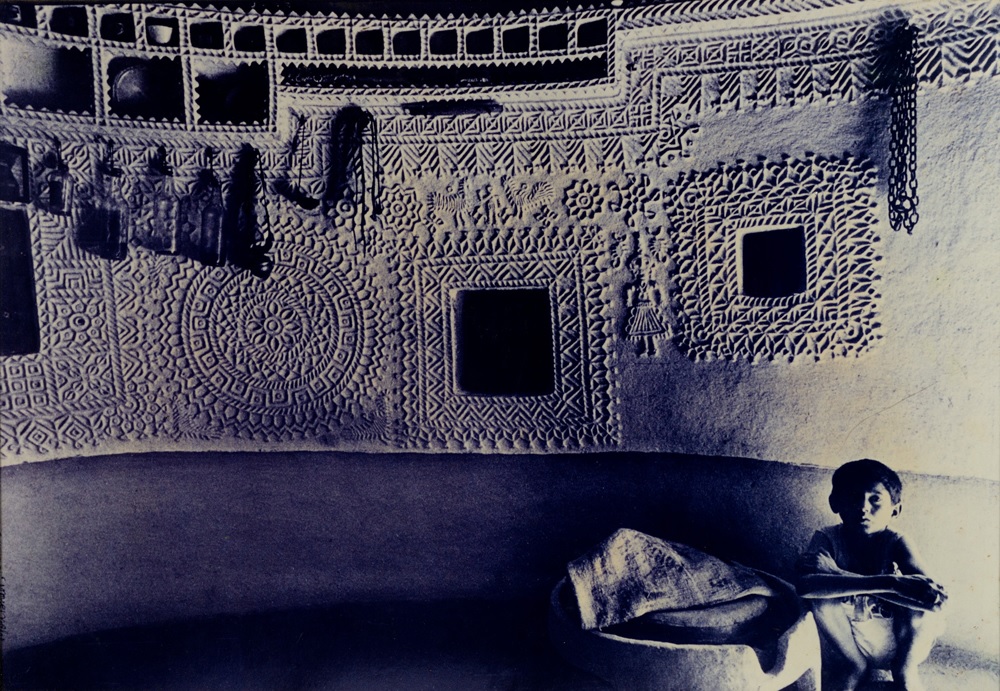

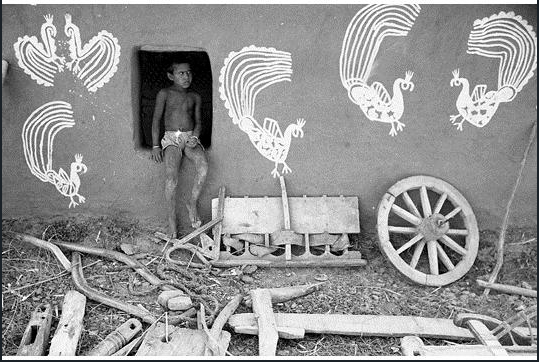

Jyoti Bhatt

Collection: DAG

Jyoti Bhatt

Collection: DAG

Jyoti Bhatt

Image courtesy: Public Domain

Jyoti BhattA founding member of the Baroda Group, Jyoti Bhatt was trained at M. S University in Baroda under K. G. Subramanyam in painting and printmaking where he developed a keen sensibility for folk forms. Bhatt also trained in fresco and mural painting techniques at Banasthali Vidyapith, Rajasthan. Combining the influences of his mentor as well as his training in medium and form, Bhatt painted numerous murals throughout his career including a mural at Kala Bhavana of the Banasthali Vidyapith. Bhatt was also a prolific documenter of folk art and architecture across Gujrat, with photography becoming his medium for exploring the conflation and tensions between art and craft—something which acted as a strong influence on his mural compositions. Between 1950-56, Bhatt was commissioned to create two murals for the Parliament House in New Delhi. |

|

The works of all these artists drew from regional and indigenous sources as well as global trends and sociopolitical events, swiftly working within the space of conflation and tension between the two. Their interventions into the built environment are embodiments of a modernist discourse informed by global thought but rooted in regional thoughts and practices, visible in the city spaces we inhabit every day. |

|

|