Mehfil-e-Thumri: Representing Performers in Colonial India

Mehfil-e-Thumri: Representing Performers in Colonial India

Mehfil-e-Thumri: Representing Performers in Colonial India

collection stories

|

|

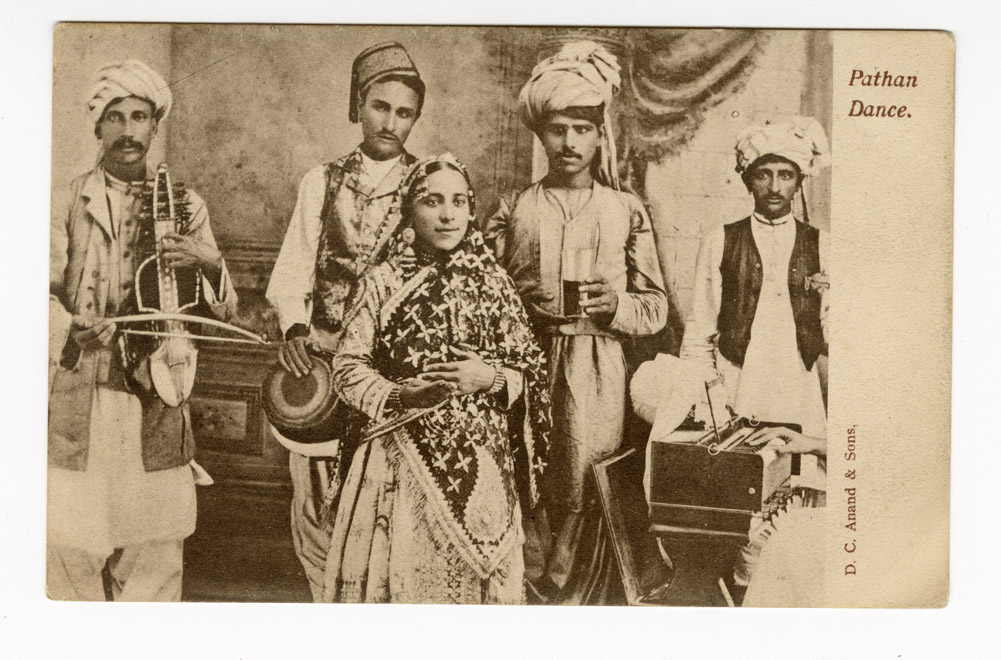

D. C. Anand & Sons

Pathan Dance

Collotype, divided back, early 20th century

Collection: DAG Archives

The title ‘Pathan Dance’, refers to a particular group of people usually residing in the north and northwest regions of South Asia. Although the title specifies dance, it is quite possible that the 'dancer' portrayed here was also trained as a vocalist. In case of women, no distinction seems to be evident between singers and dancers. Many of the great women singers of the past were skilled dancers and the traditional craft of the tawayef included dancing as one of its essential elements. |

Phototype Co., Bombay

Singing Party

Collotype, undivided back, early 20th century

Collection: DAG Archives

This postcard, produced by The Phototype Company, Bombay presents four women seated with three male musicians. The Phototype Company was a prolific producer of postcards in the early 20th century—printing postcards by other companies while also creating their own with images usually depicting views of Bombay or cultural scenes. The women are draped in sarees and minimal jewellery which also diverges from the popular visualisations of performers in the early twentieth century. The caption, Singing Party, seemingly clarifies the logic of divergence by identifying those depicted as singers and removing the association of dance from the largely overlapping categories that constituted performance. Due to long exposure times, it would be impossible to capture performances in motion and therefore performers were staged or made to pose. |

|

From the beginning of the nineteenth century, the progressive decay of the North Indian centers of patronage of music caused traditional practitioners of music to leave their ancestral homes to seek employment in metropolises like Calcutta and Bombay, where mercantile trade and proximity to the seat of colonial and political power had created an assorted class of patrons. Even during this turbulent period, women singers maintained control over the kotha, transforming it into a significant venue for musical exchange and dissemination, including for male singers. Rather than merely being seen as a space for sexual gratification, the kotha served as a vital musical institution, playing a crucial role in the organisation of music. This challenged the assertions of traditional occupational groups that claimed to be the sole custodians of specific musical knowledge. |

|

|

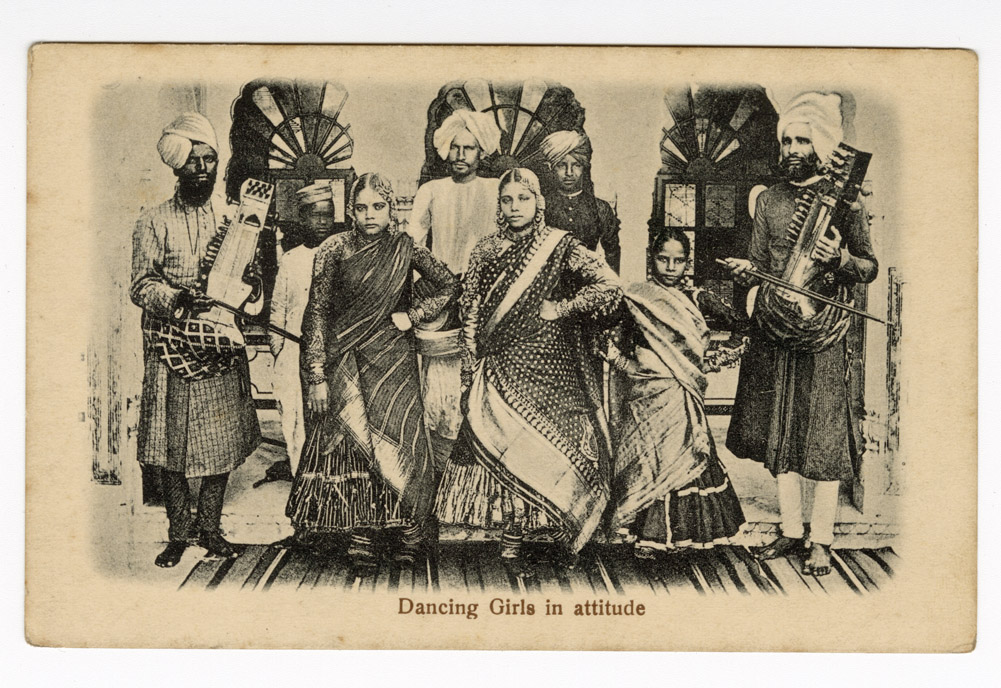

Unknown Publisher

Dancing Girls in Attitude

The inner Music Room of the Ramdulal Nibas in Kolkata.

Photographer: Vinayak Bose

Prahlad Chandra Karmakar

Untitled

1934, Oil on canvas pasted on board, 12.2 x 21.0 in.

Collection: DAG

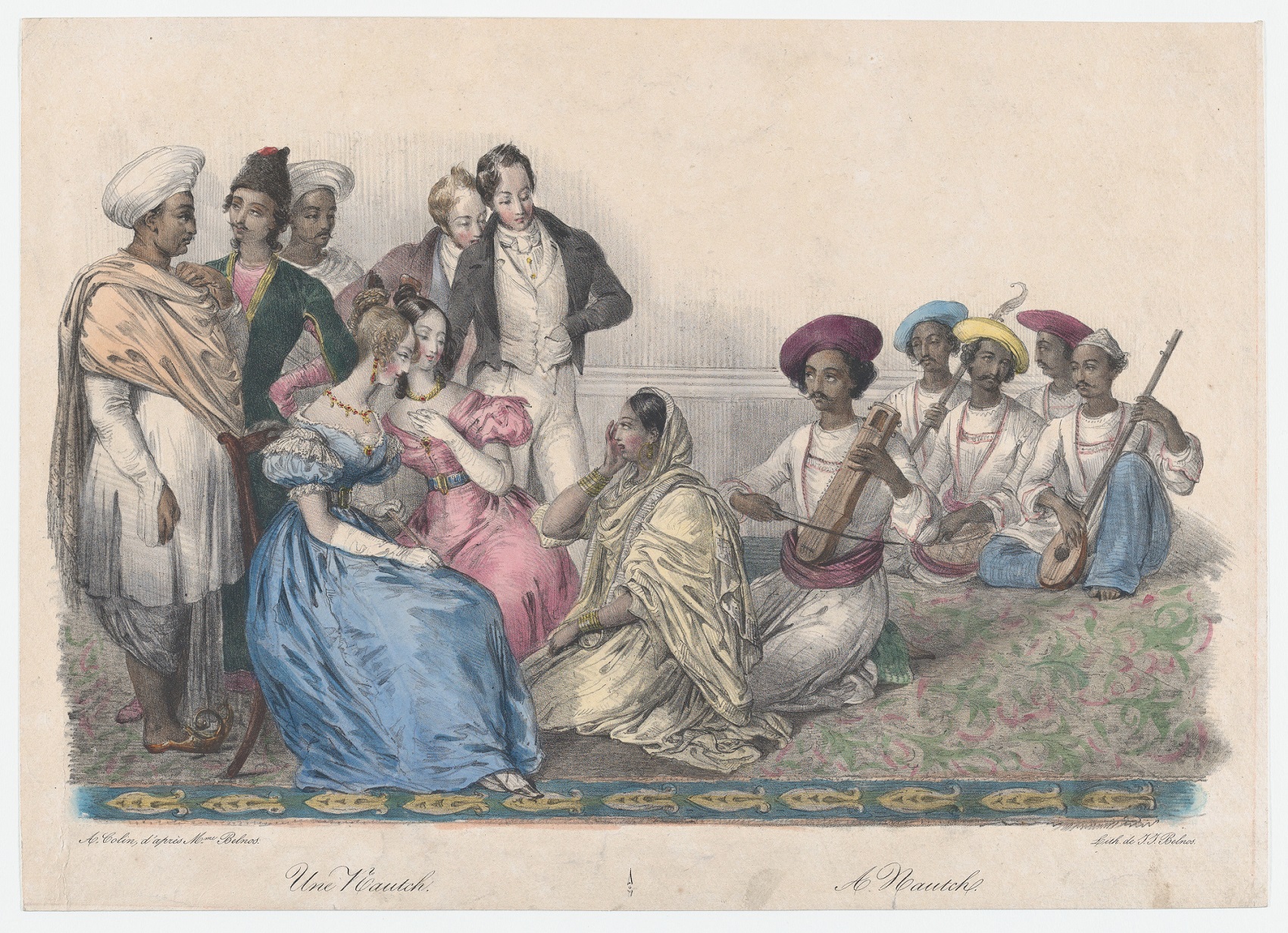

With the decline of the Mughal Empire and other princely states, musicians began to seek new clients and patrons among the landed gentry and the bhadralok, or genteel class. These groups were eager to adopt the artistic preferences of earlier patrons of North Indian art and music while also engaging with a broader Indian cultural sphere influenced by Mughal traditions. The nautch became a popular form of entertainment for Indian merchants hosting English guests. In Hobson-Jobson, there is an account of a European woman who had been invited to 'go to a nach given by a rich native, Rouplall Mullich, on the opening of his new house.' |

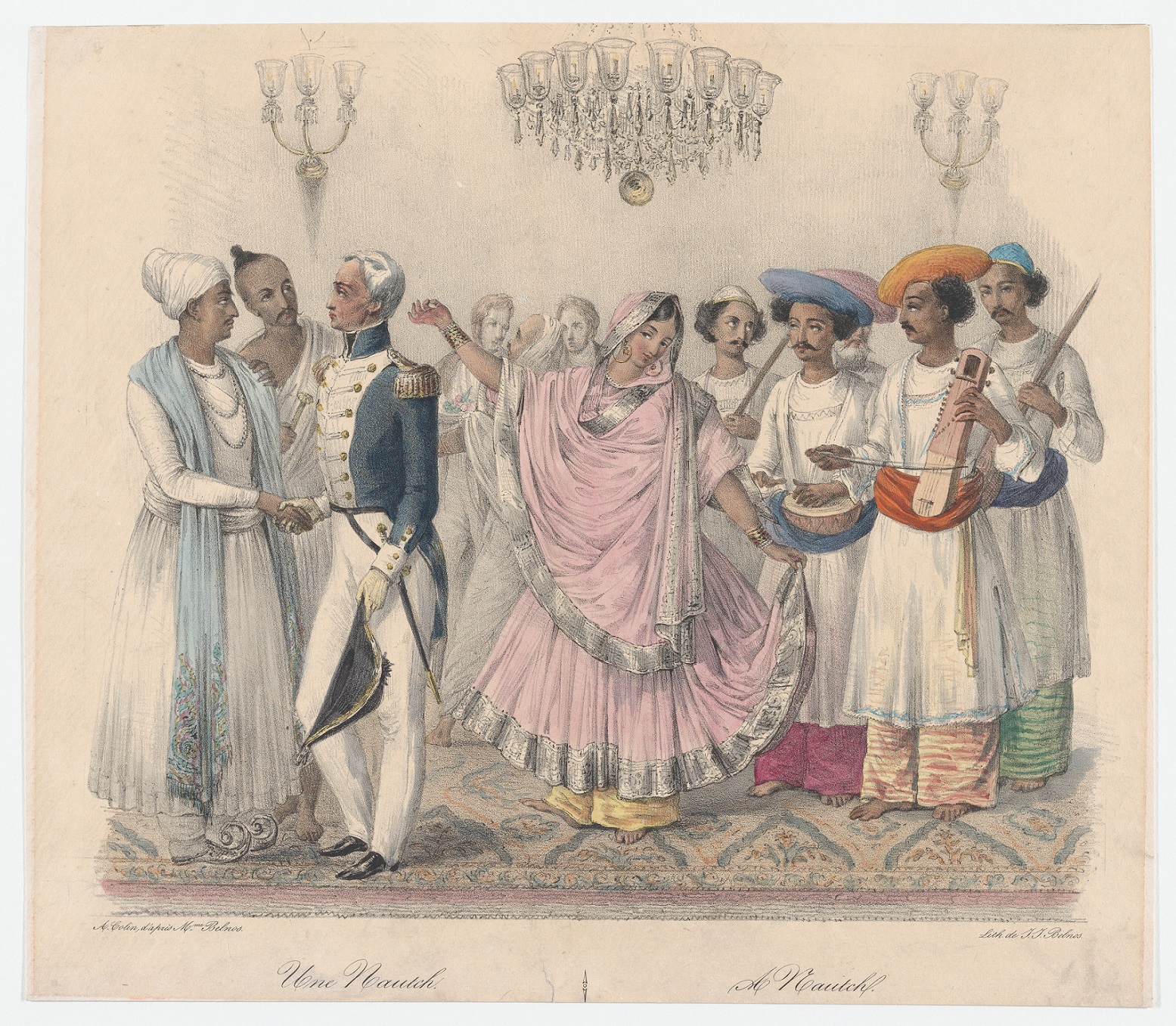

Alexandre-Marie Colin, Jean Jacques Belnos, after Mrs. Belnos

Une Nautch; from Twenty four Plates Illustrative of Hindoo and European Manners in Bengal

1832, Collection: The MET. Public Domain

During his visit to India in 1849-50, his friends smuggled American author and critic Charles Eliot Norton into a nautch reserved for a distinguished Indian audience. He wrote: 'In this upper room was the most distinguished of nautch girls performing before the umeers. The slow dancing or rather gliding movement is very little cared for, it has little grace, and after commencing with it for a few moments the girl sits on the floor to sing. This girl, whose name is Hera, is the most celebrated of all for her voice. It is low, but as far as I could judge not complete contralto. The accompaniment of stringed instruments is entirely ad libitum and is constantly, I think, in one key, and not very loud. Still, as the singer and the musician have no concert you often hear discords… To a stranger the music is quite uninteresting, but I have no doubt it would become less so the more you heard.' |

Unidentified Photographer

Nautch Girls and Musicians, Silver albumen print on paper, c. 1880s. Collection: DAG Archives

Alexandre-Marie Colin, Jean Jacques Belnos, after Mrs. Belnos

Une Nautch; from Twenty four Plates Illustrative of Hindoo and European Manners in Bengal

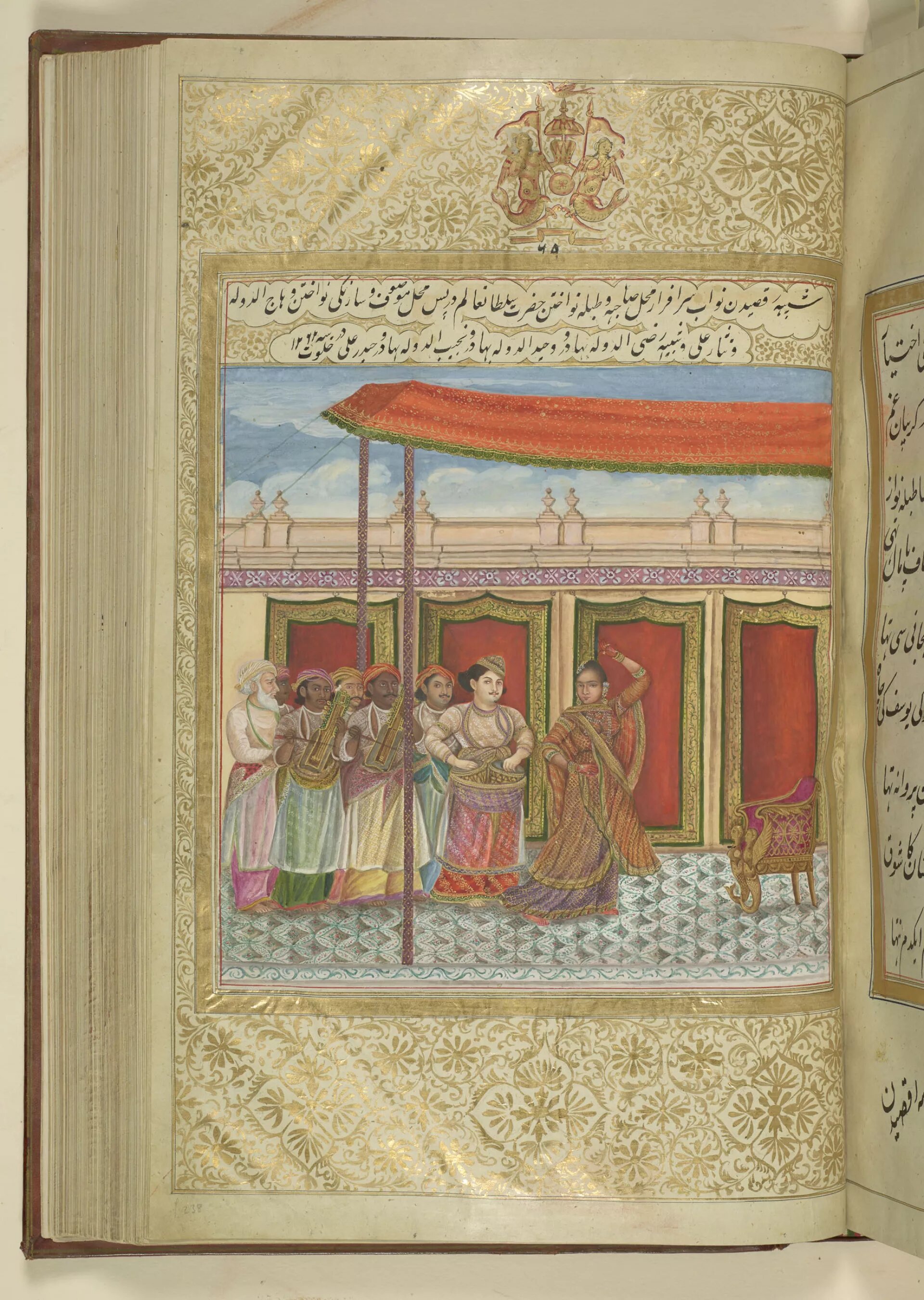

Sarafraz Mahal dances as Wajid Ali Shah plays the tabla, as depicted in the 'Ishaqname'.

1850, Painting in opaque watercolour including gold metallic paint with ink over traces of graphite on paper

Image courtesy: Royal Collection Trust

Did you Know?In most accounts of his life and career, Wajid Ali Shah, the Nawab of Oudh, is often remembered as a hedonist or a political failure who succumbed to the machinations of the East India Company. These portrayals, largely derived from colonial sources, depict him as an irresponsible ruler in the lead-up to annexation and its aftermath. However, in cultural histories, Wajid Ali Shah is recognized for his contributions to the arts, having invented new rāgas and developed genres of song and dance, particularly thumri and Kathak. He fostered a taste for light or 'semiclassical' music that remains popular today. Moreover, his exile to Calcutta is acknowledged as a pivotal moment that enhanced the city's status in the arts and significantly impacted classical music across northern India. |

Attributed to Samuel Bourne & Charles Shepherd

The Delhi Nautch

Photomechanical print on paper, c. 1903

Collection: DAG Archives

Attributed to Charles Shepherd, this photograph is one of the earliest commercial photographs showing a dance performance in this kind of an architectural surrounding, with its plate being produced in c. 1862-63. Two women performing with a younger girl wearing ghungroo on her feet, are next to a woman clad in a simpler saree. Six of the men standing behind them can be seen playing instruments—three sarangis and two percussive instruments resembling the tabla and a cymbal. The image corroborates the many descriptions of 'nautch' performances which describe the musicians performing while standing. These musicians accompanying the courtesans, primarily tabla and sarangi players, were often regarded as procurers. In the years since independence, they had to negotiate their new notoriety and find ways to reclaim their instruments. |

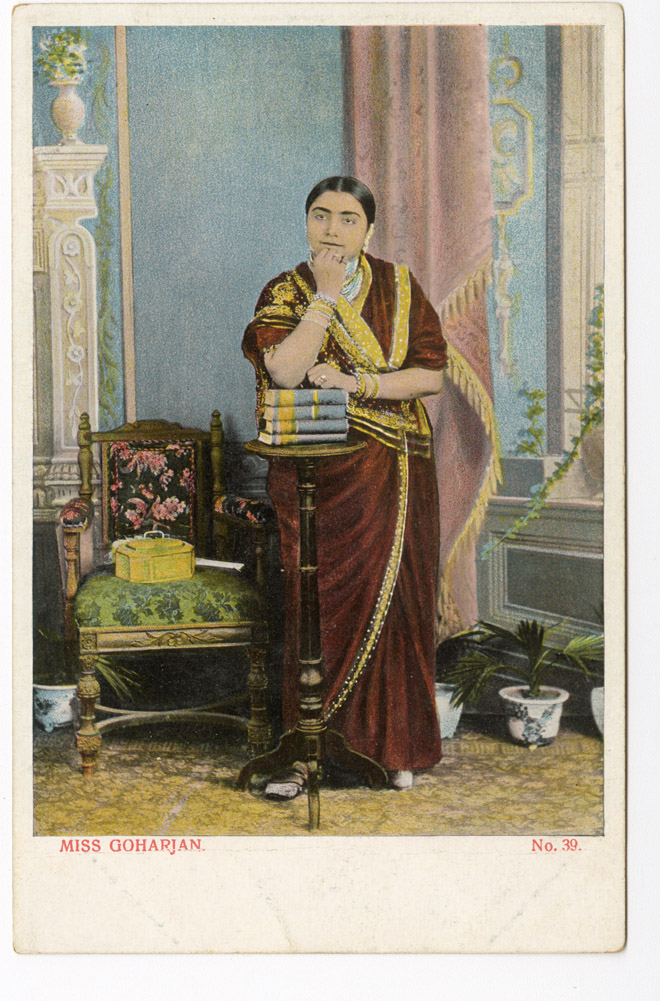

D.A. Ahuja, Rangoon

Miss Goharjan

Coloured offset, divided back, early 20th century

Collection: DAG Archives

D. A. Ahuja, a photographer from Punjab, settled in Rangoon (now Yangon) and became the proprietor of the largest postcard firm there which produced postcards from their own photographs as well as from other popular photographers like Felice Beato. Bai Gauhar Jan, became one of the first recorded vocalists in India. This is a seminal point in the history of Indian music, because this is the first time that different kinds of traditional musical compositions were being recorded in a particular timed format, corresponding to the limits of the disc, raising fresh questions about forms, structures and combinations. |

|

Further Reading Amlan Das Gupta. “Women and Music: The Case of North India”. Women of India: Colonial and Post-Colonial Periods. edited by Bharati Ray. Pub: CENTRE FOR STUDIES IN CIVILIZATIONS. |

|

|