Material Experiments in Modernist Painting

Material Experiments in Modernist Painting

Material Experiments in Modernist Painting

collection stories

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

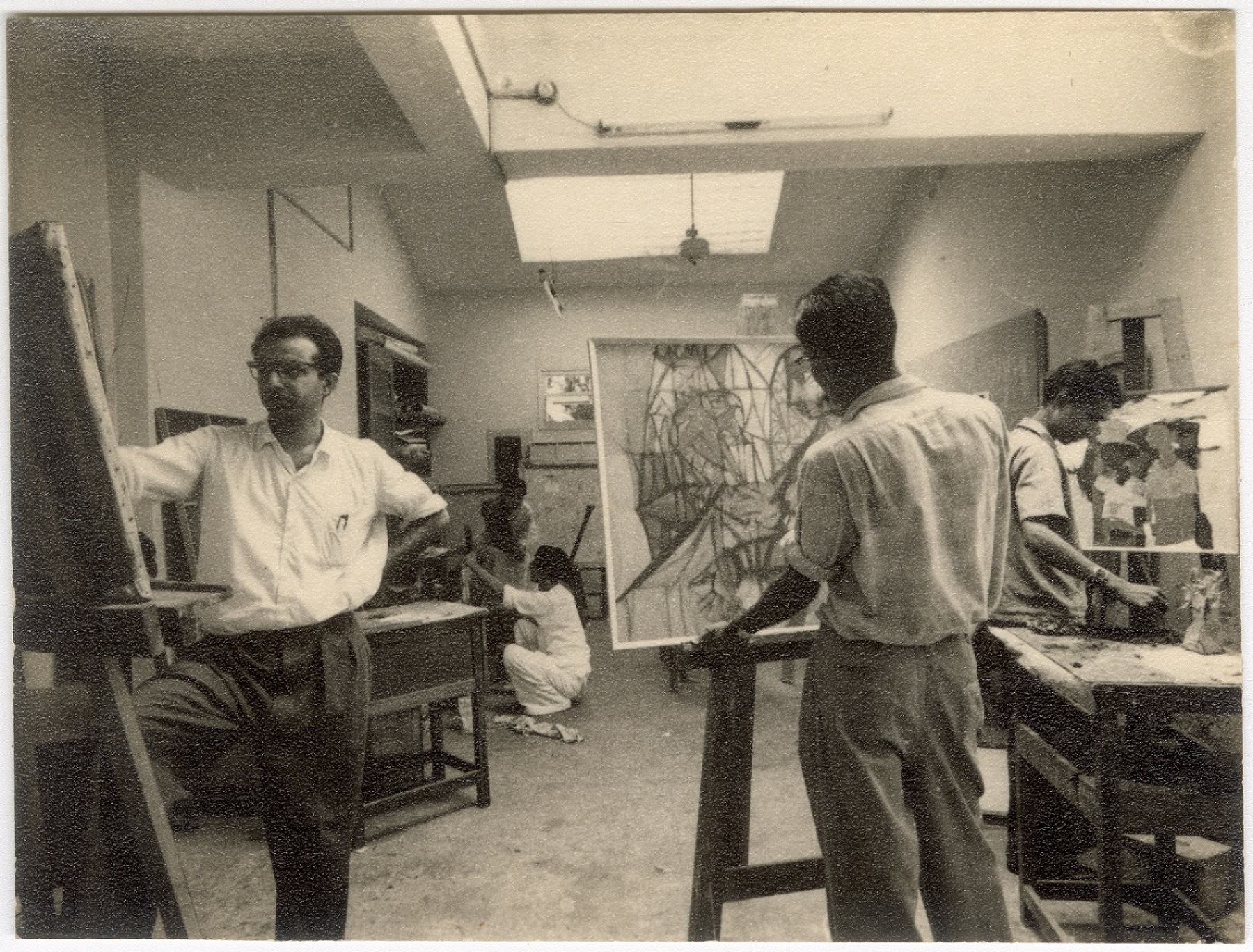

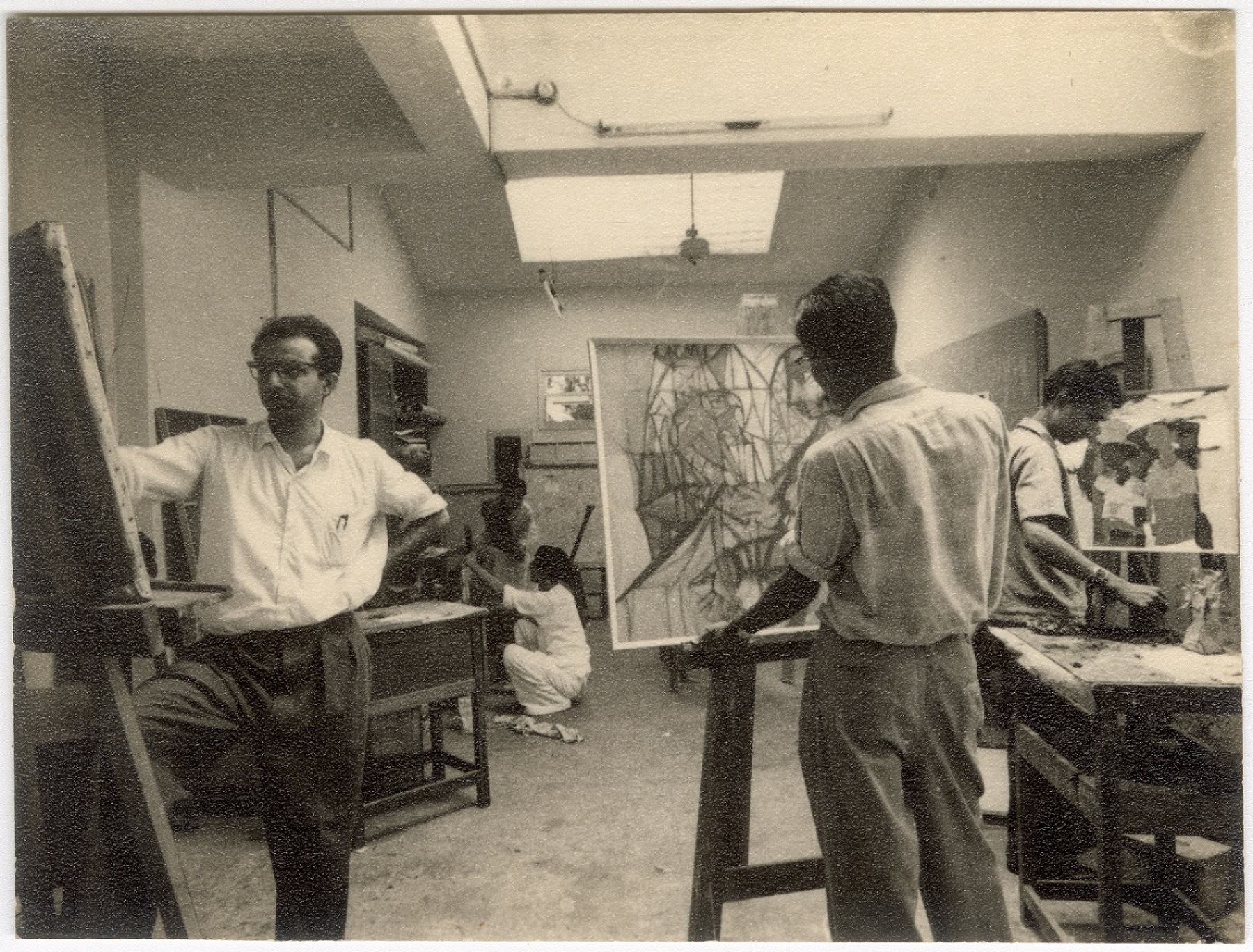

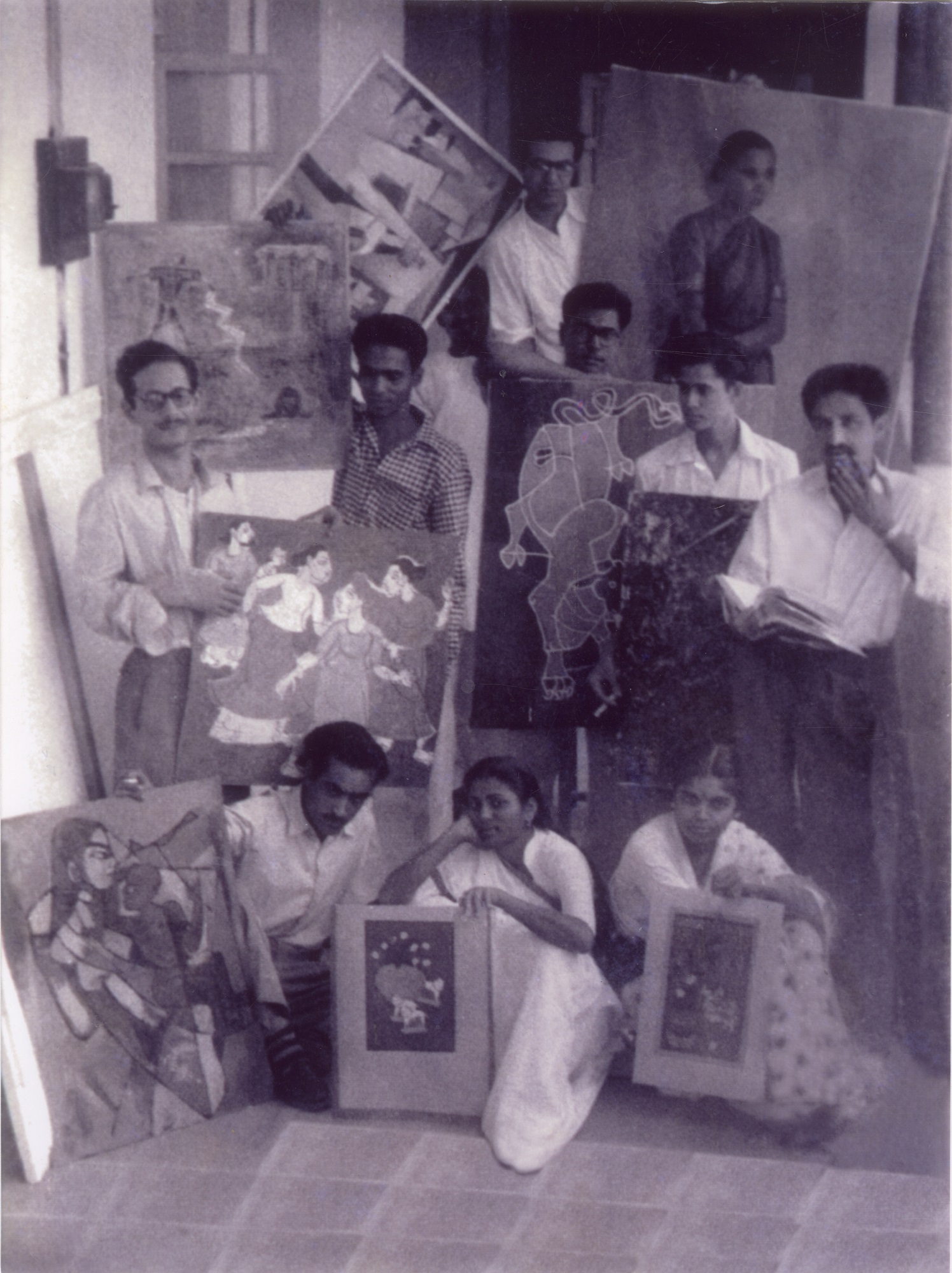

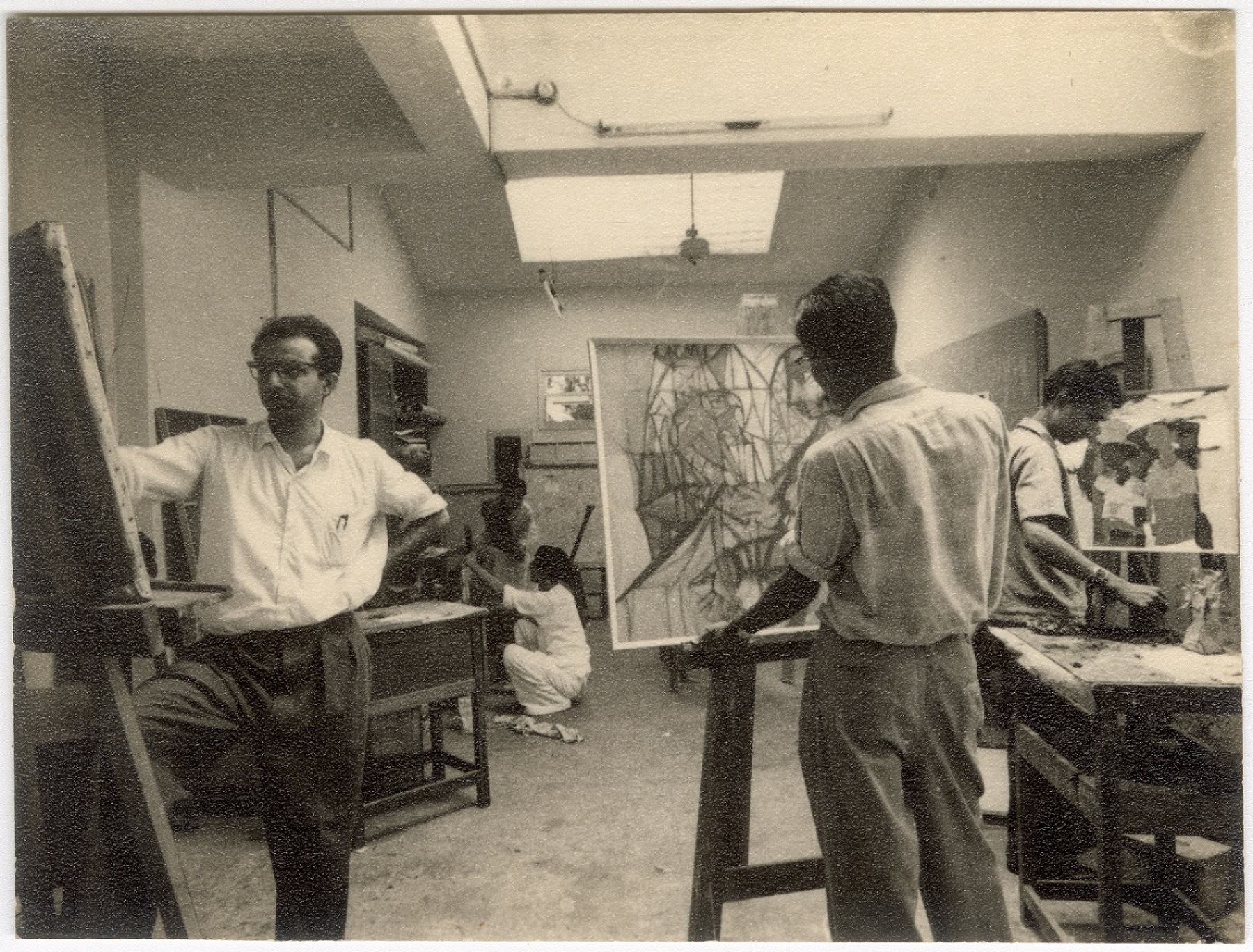

With the advent of modern art movements, there has been a constant attempt to break away from the norms of making art that prevailed for past many centuries. The traditional methods of painting, sculpting, carving or drawing gave way to more daring and uncanny material explorations. ‘The medium is the message’, as media theorist Marshall McLuhan would have put it. And that led to legendary innovations in medium and savoir-faire or artifices devised by the artists that produced and still produce marvellous art. In the twentieth century, Indian artists strived to push the boundaries of art as the epoch of colonial domination was nearing an end. Art schools like Kala Bhavana in Santiniketan and the Faculty of Fine Arts in Baroda breathed new life into the outdated and drab colonial policies of art and craft education which were mandated by the British academicism prevalent in the major arts schools in India. Artists’ groups like the ‘Calcutta Group’ and ‘Bombay Progressives’ in the 1940s, Baroda Group in the 50s and ‘Group 1890’ in the 60s—all of these collectives upheld the values of individualism and creative freedom. |

|

|

|

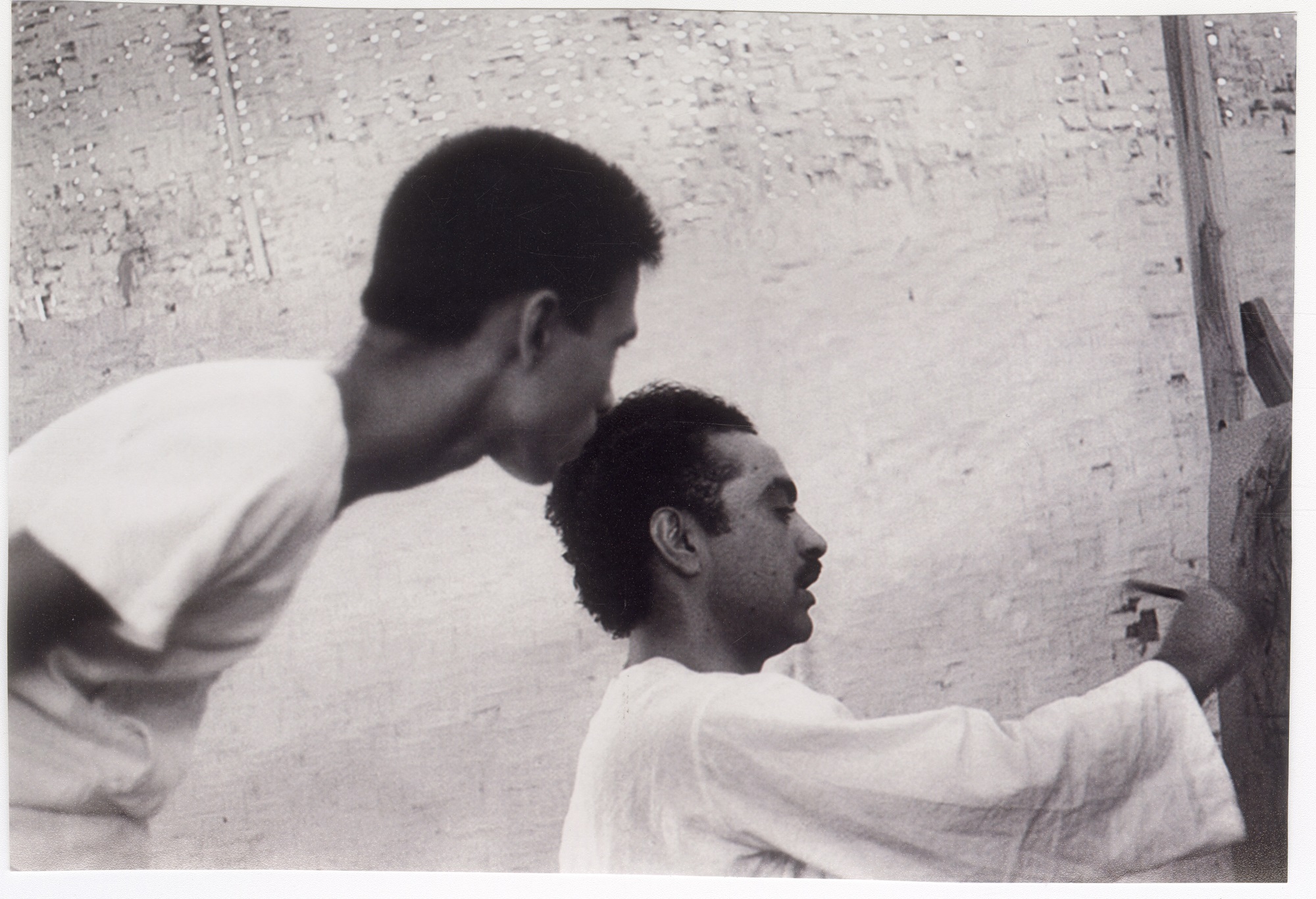

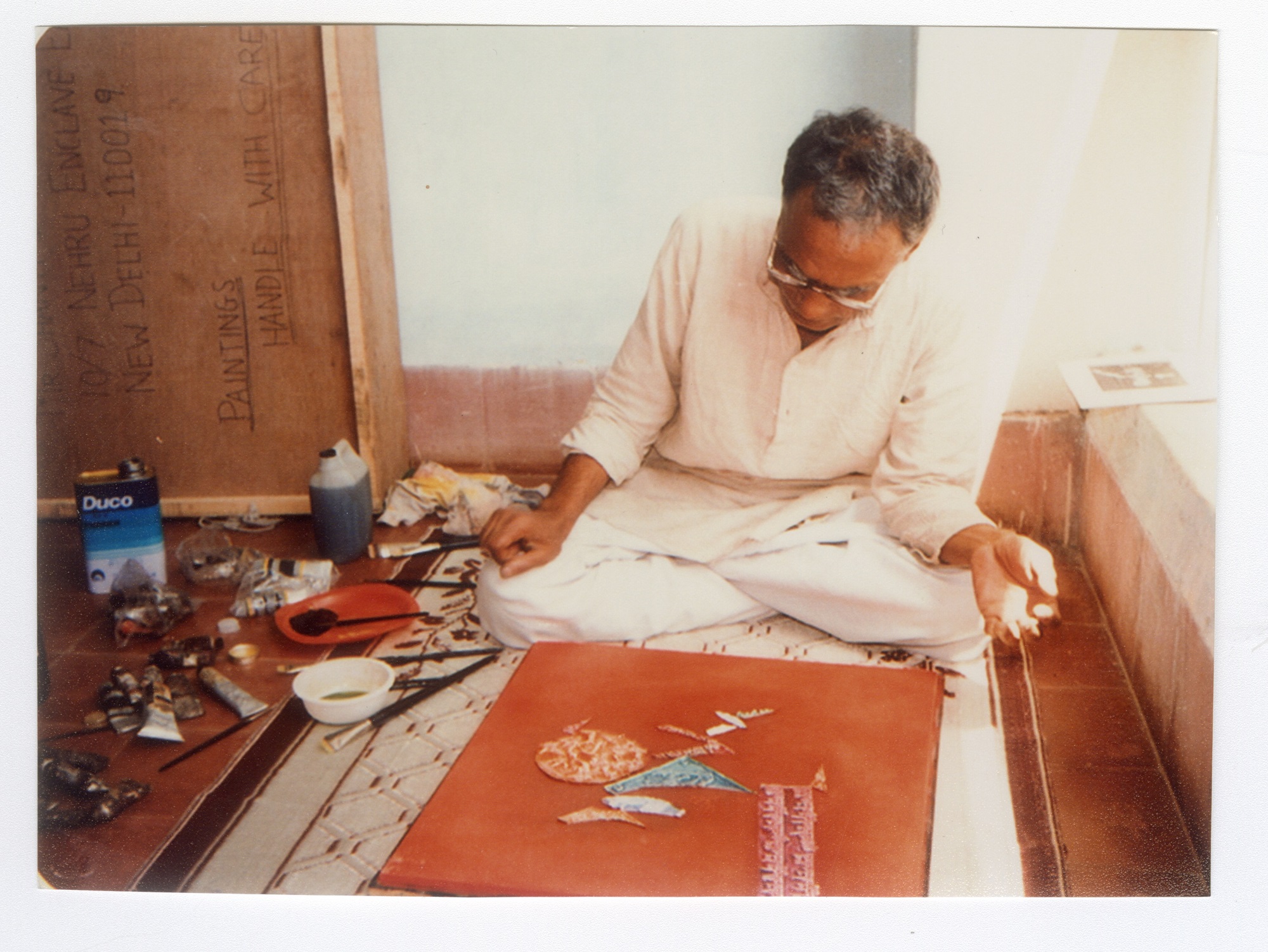

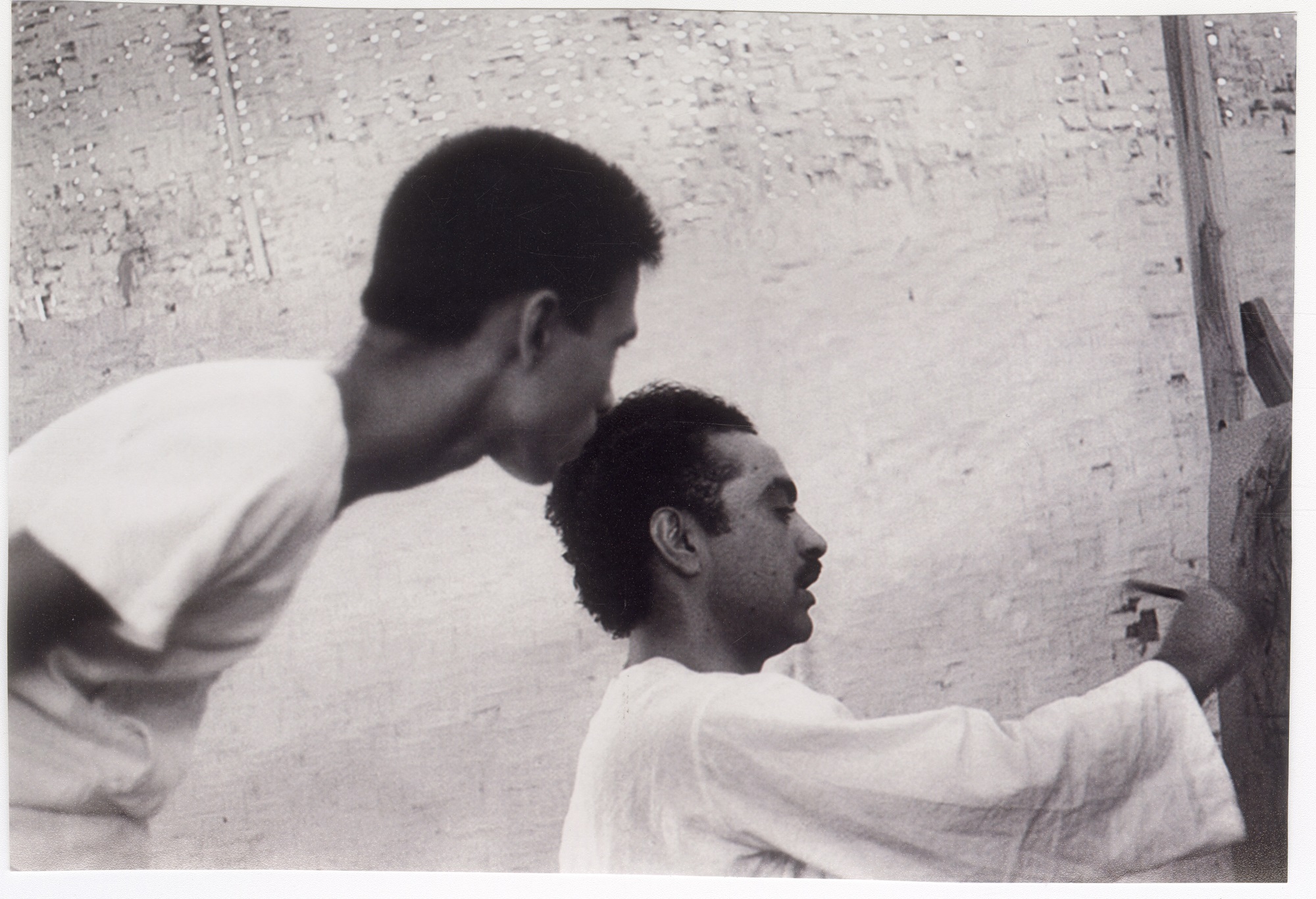

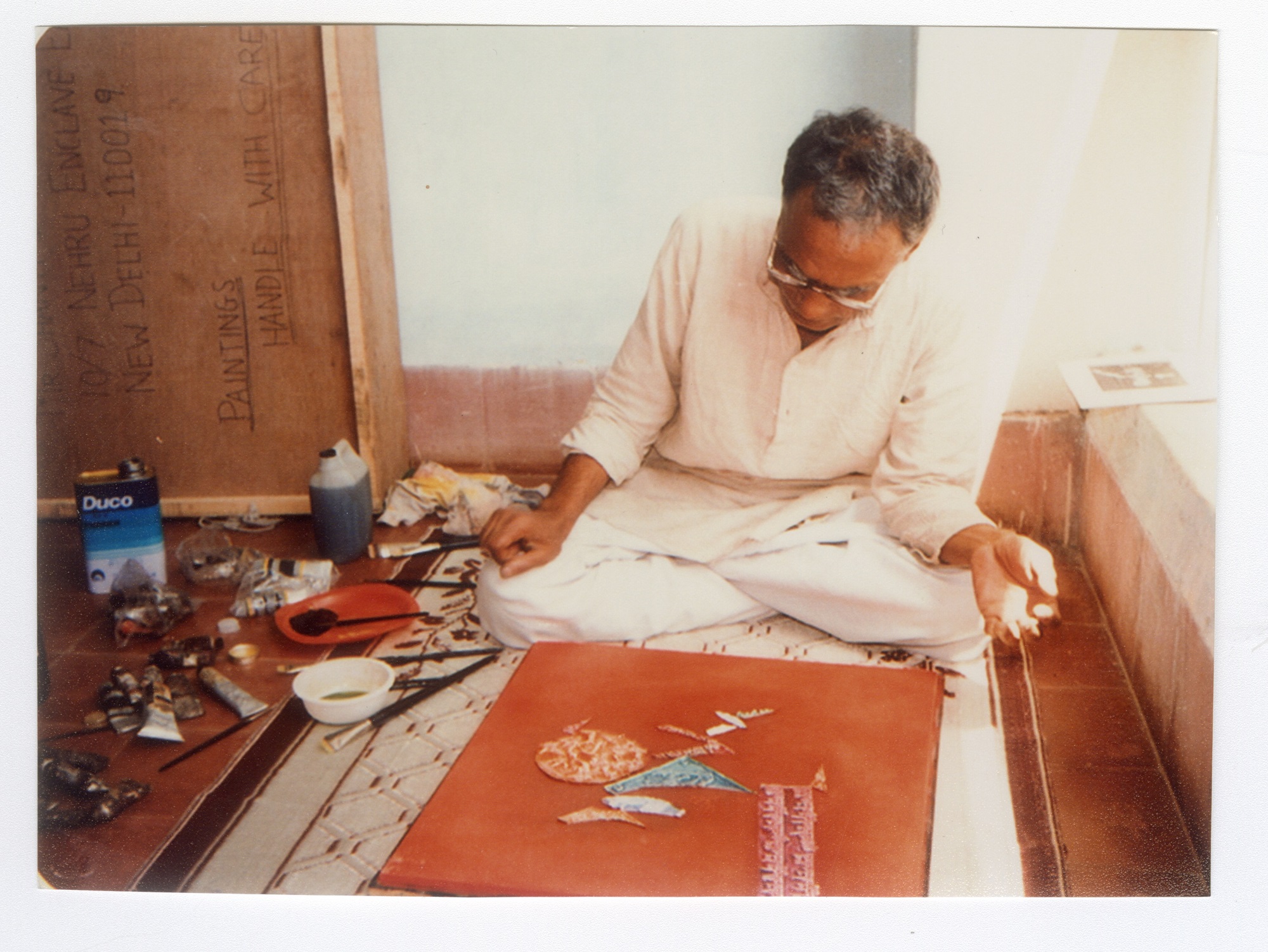

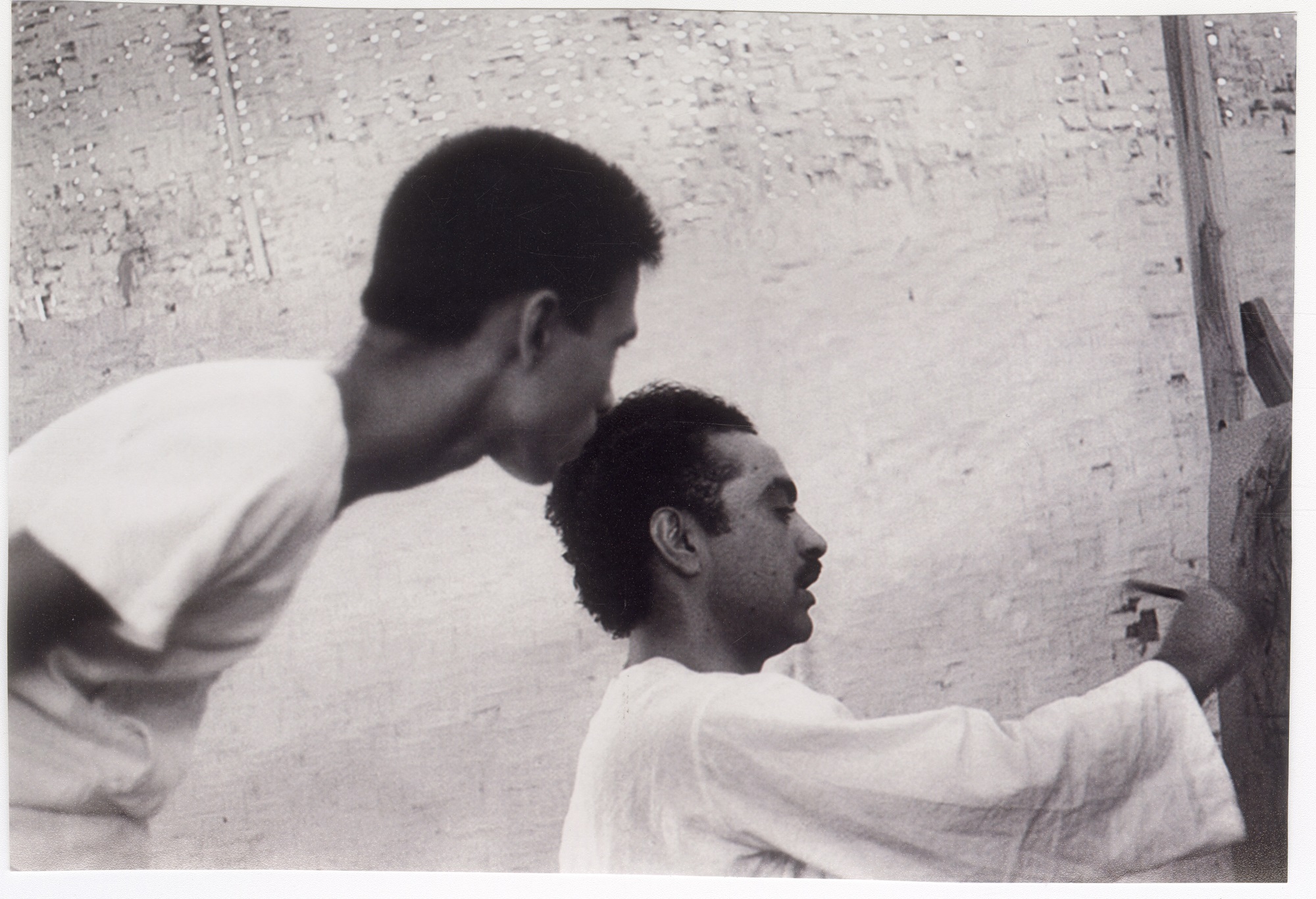

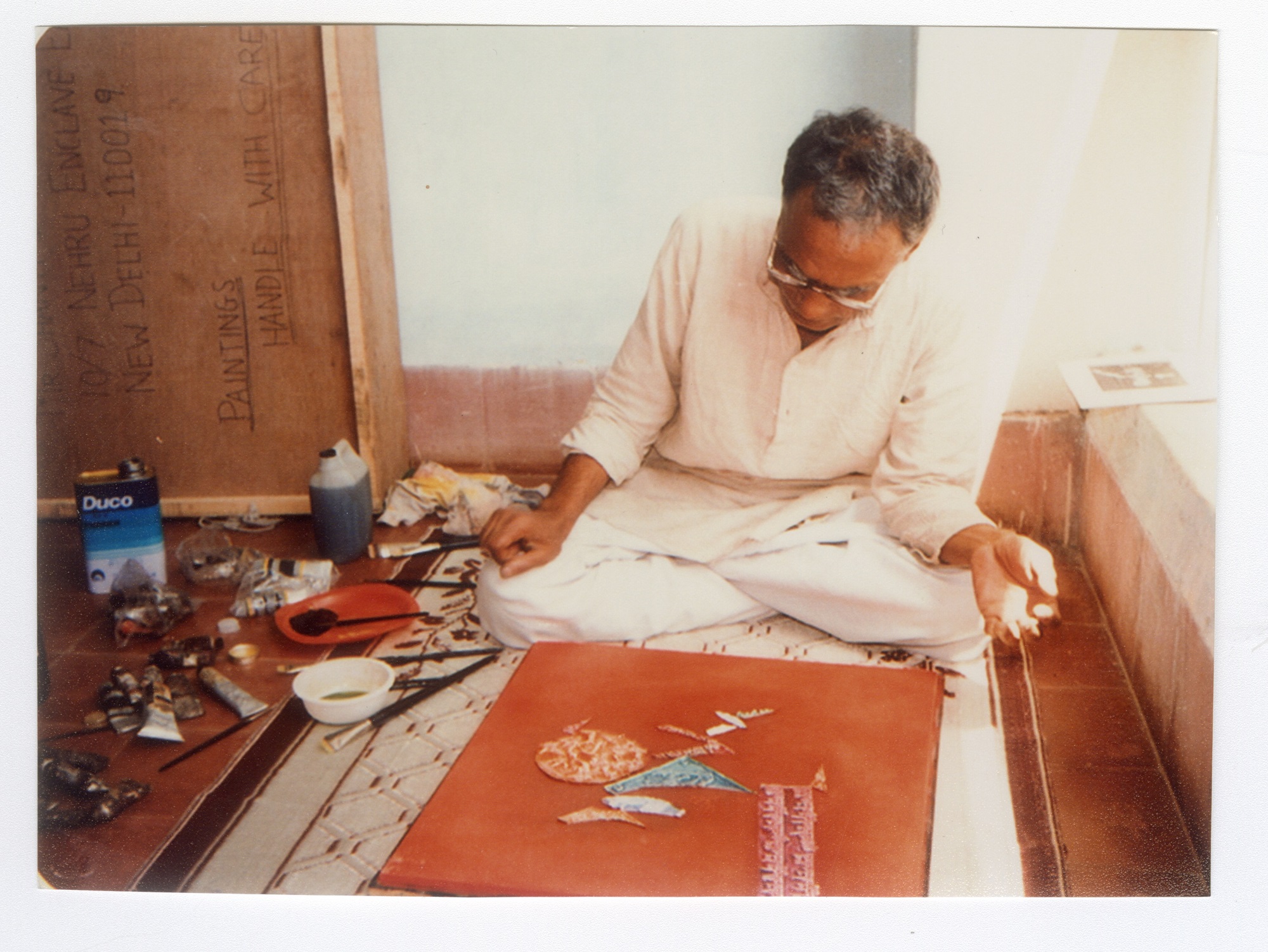

Two of the Foremost Indian Painters Experimenting with Media We have picked two artists from our vast collection of paintings by modern Indian artists who belonged to the same generation of post-colonial Indian art—Sohan Qadri and Shanti Dave—who could bend the conventional approaches to making paintings so that they could tell their own unique stories in their inimitable style. Drawing from these artists’ archives, we will also see that their uncanny methods of working tell us a lot about them, often more than the artworks could ever have. |

|

|

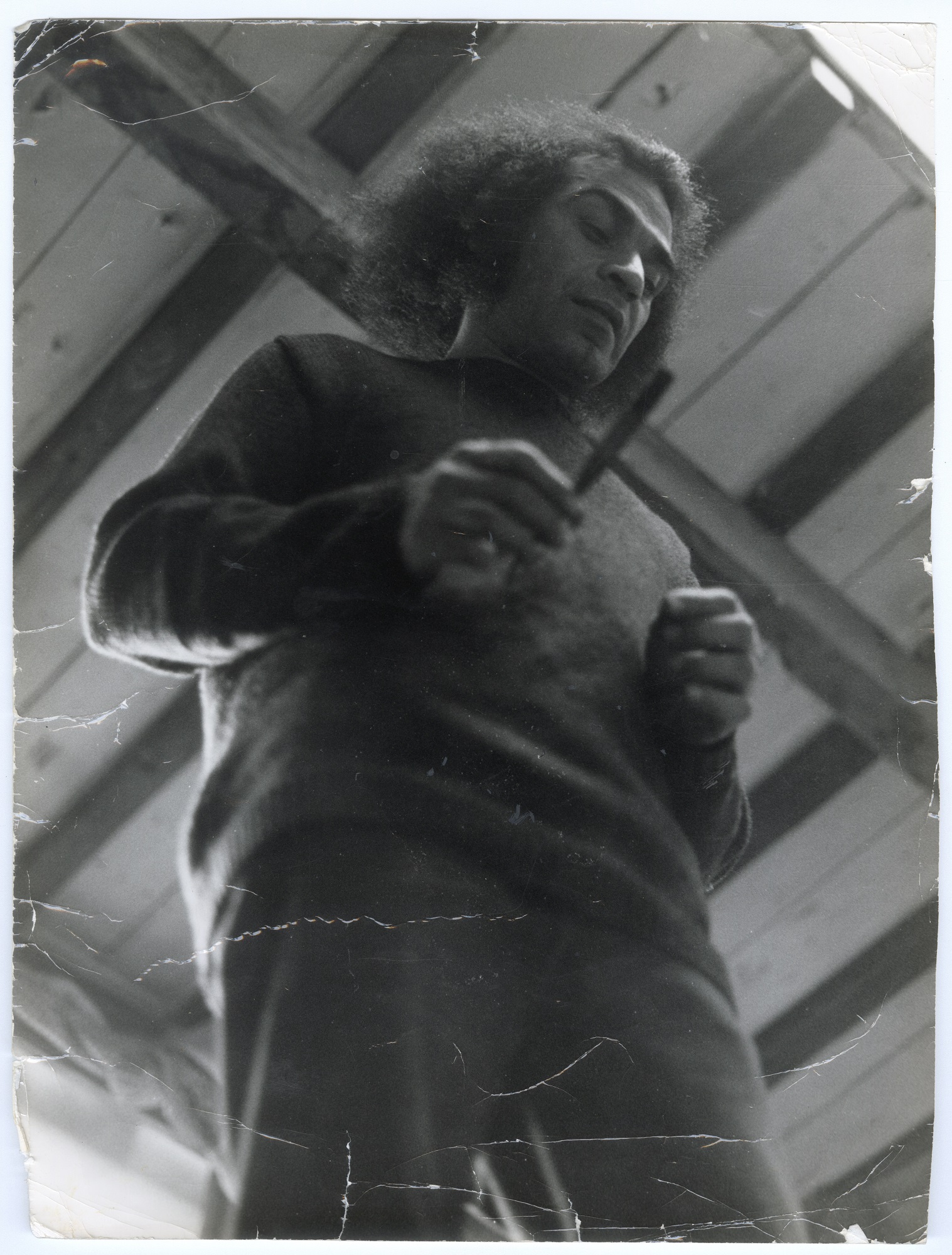

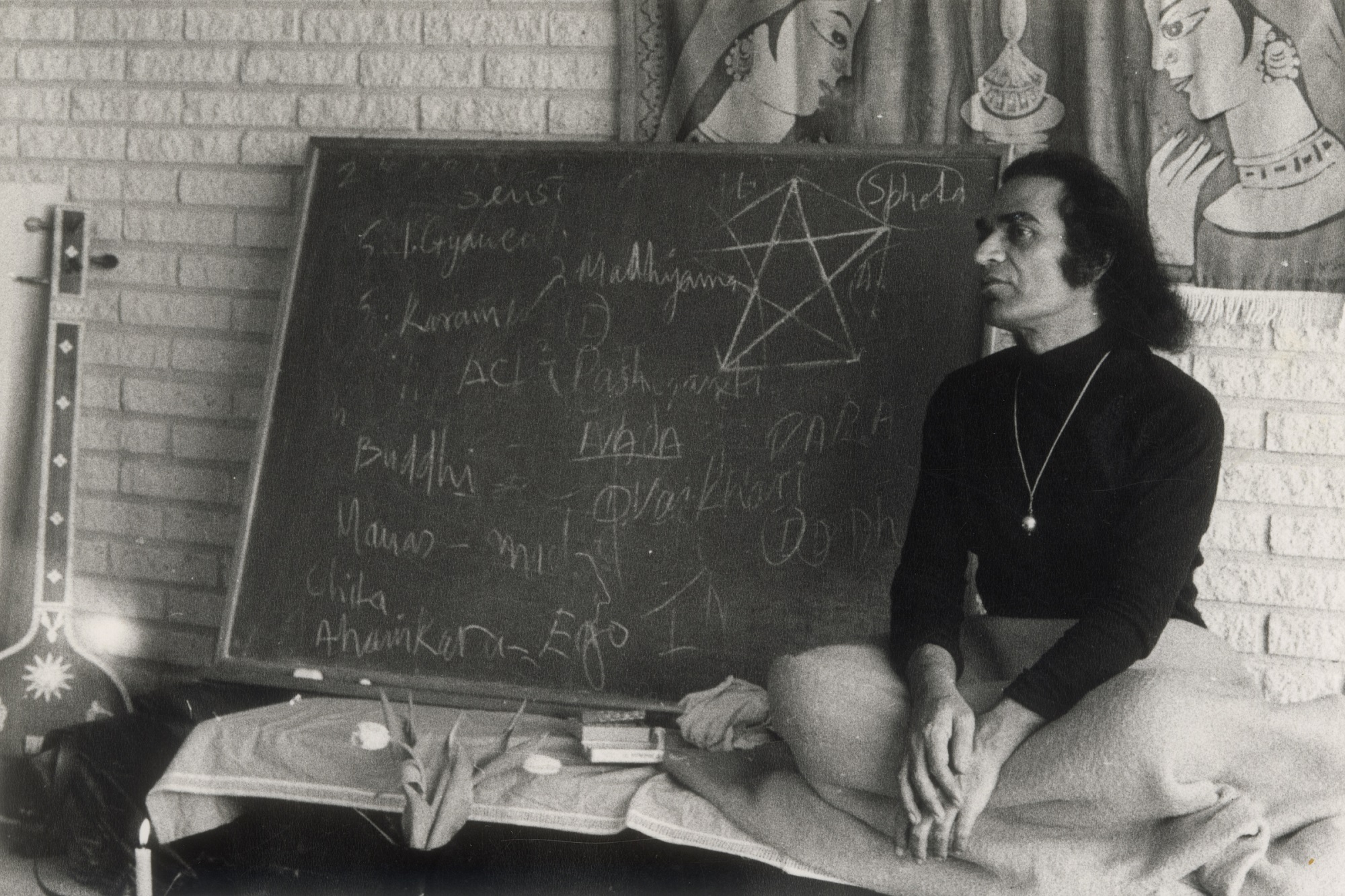

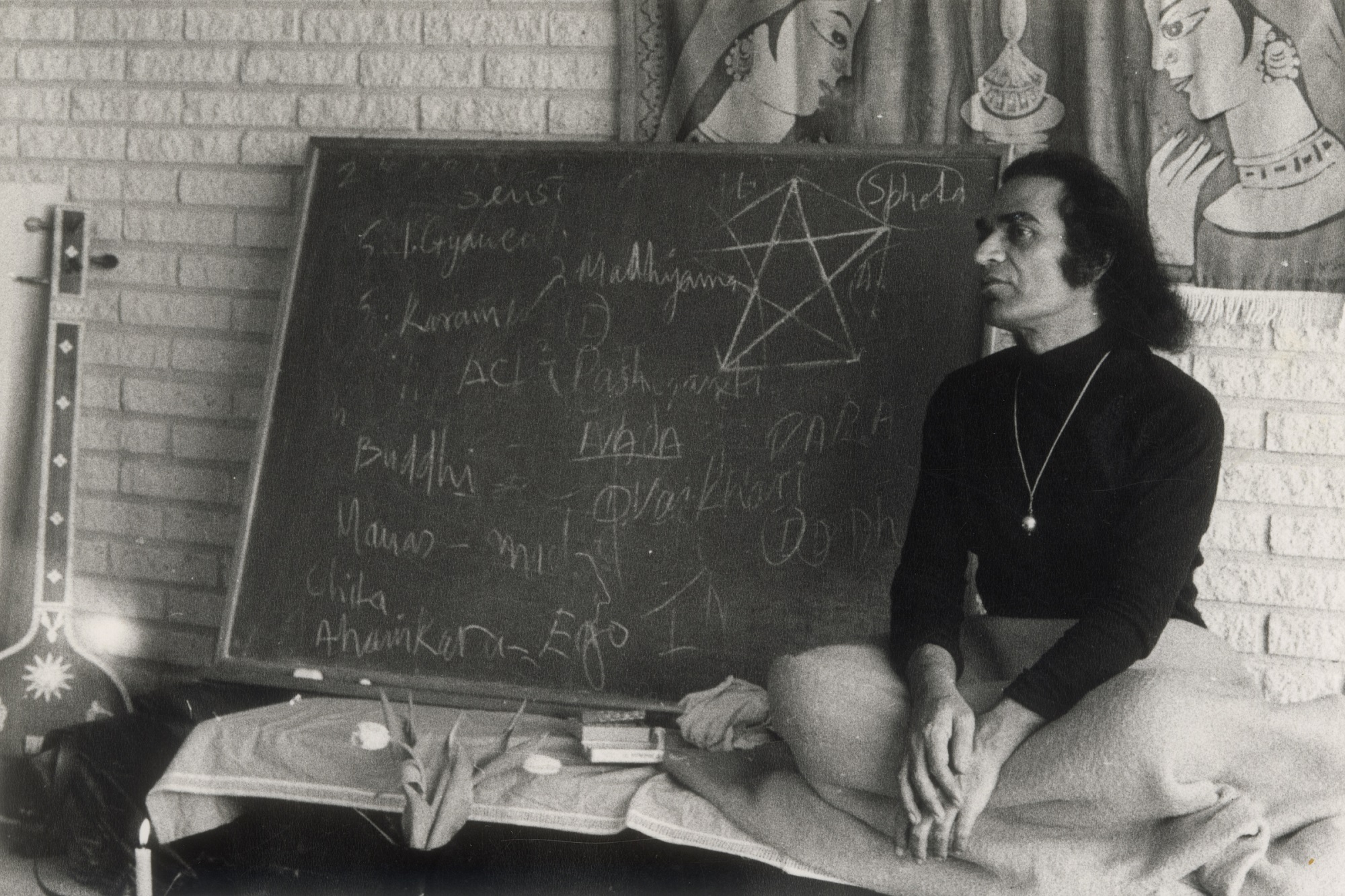

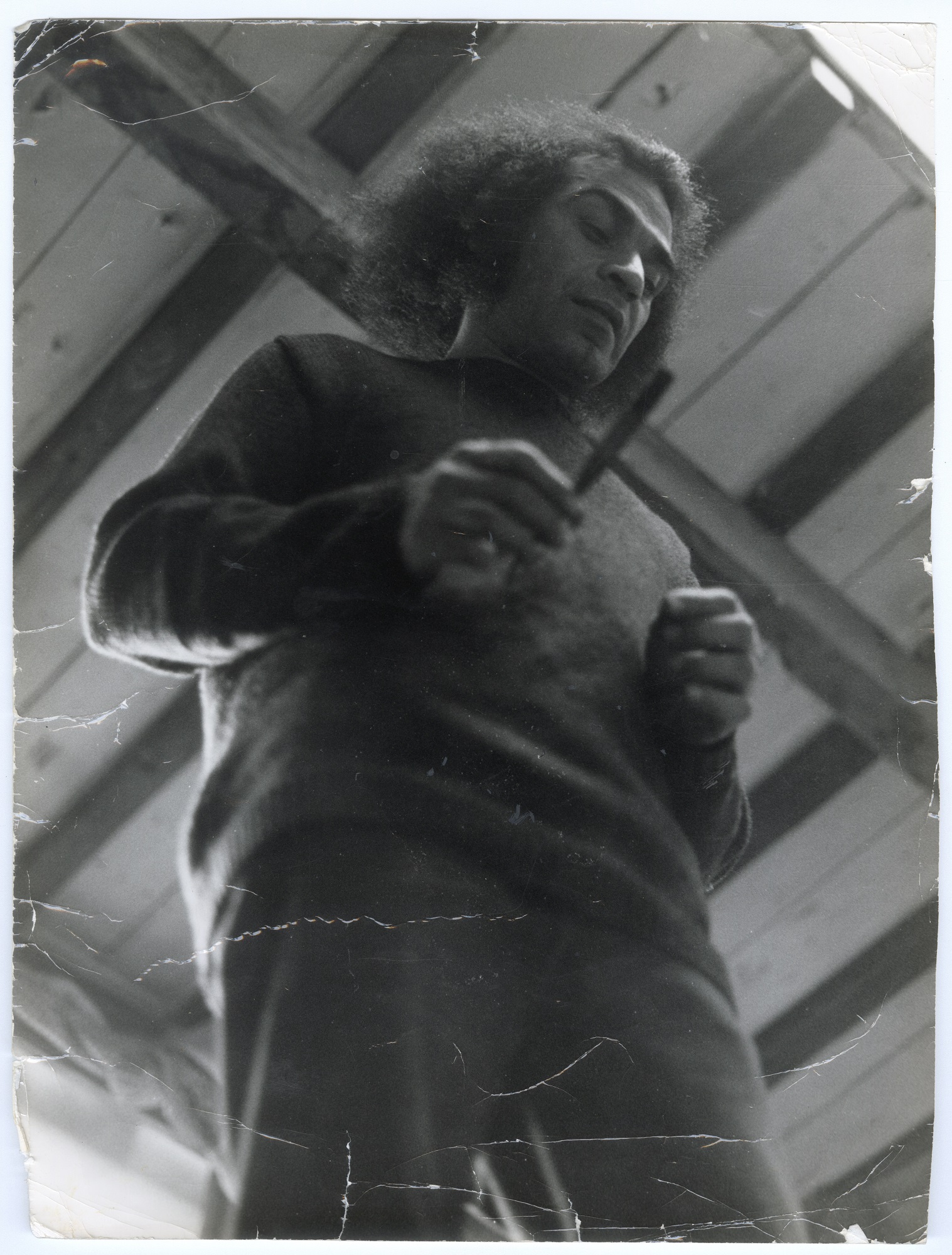

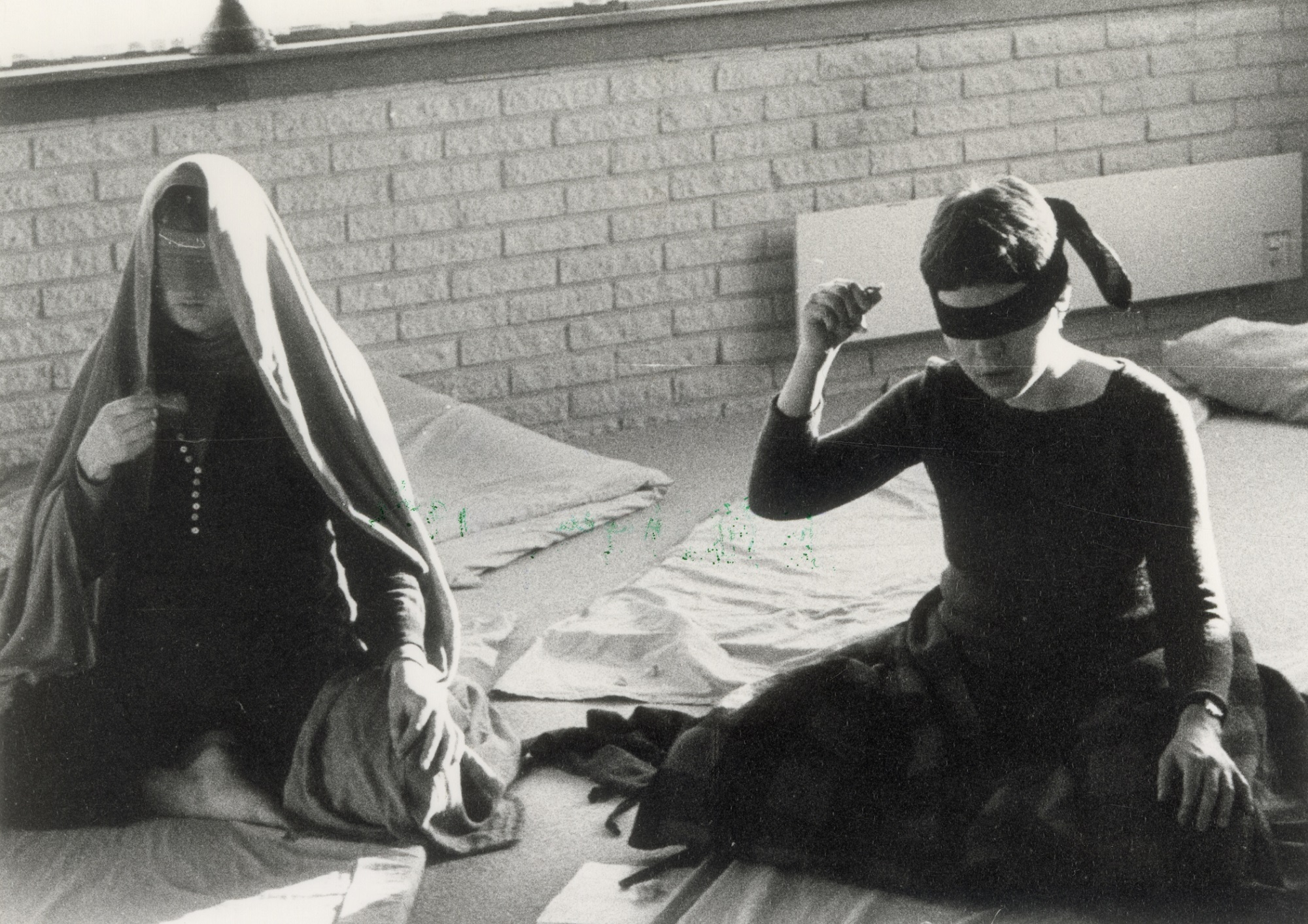

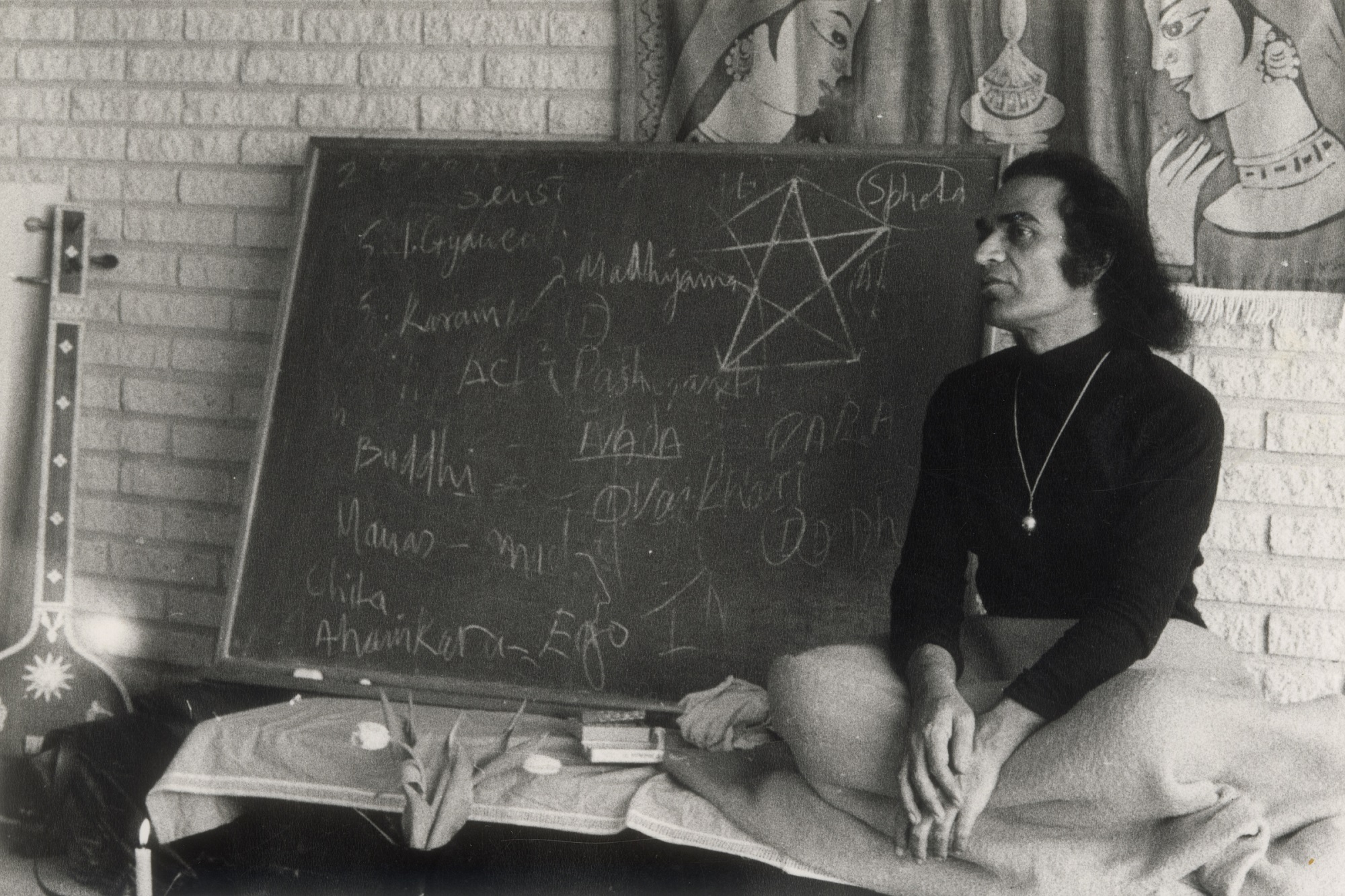

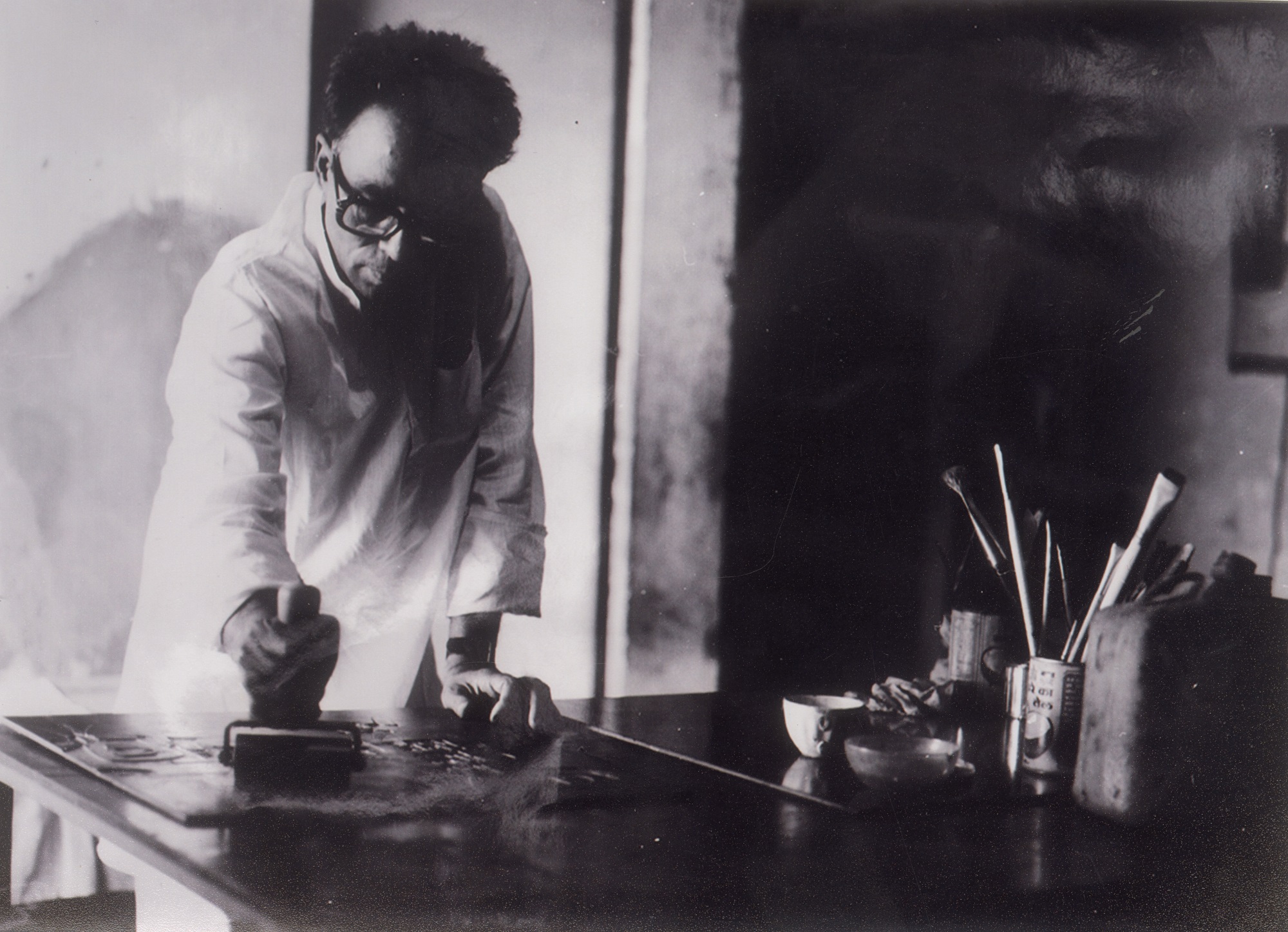

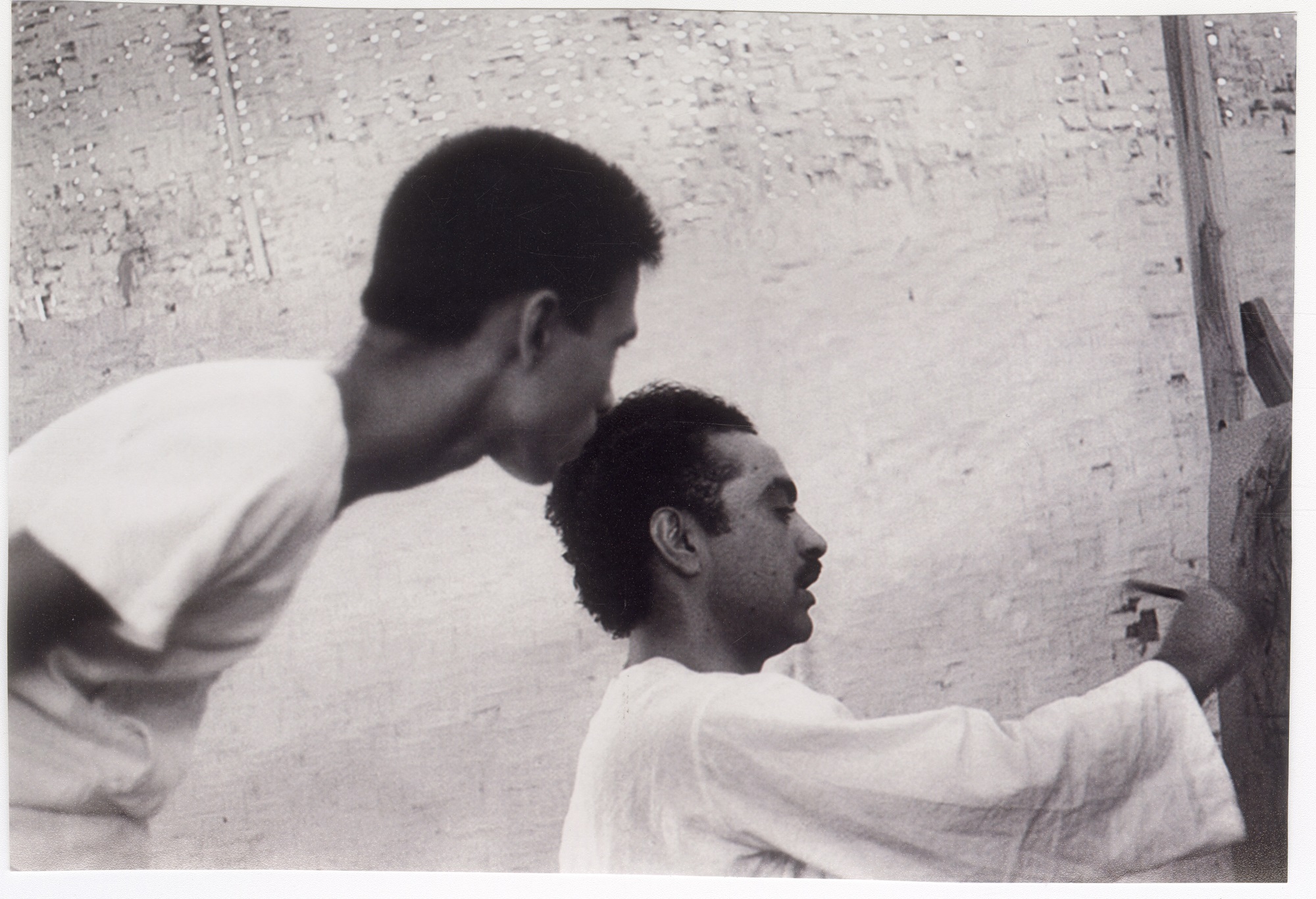

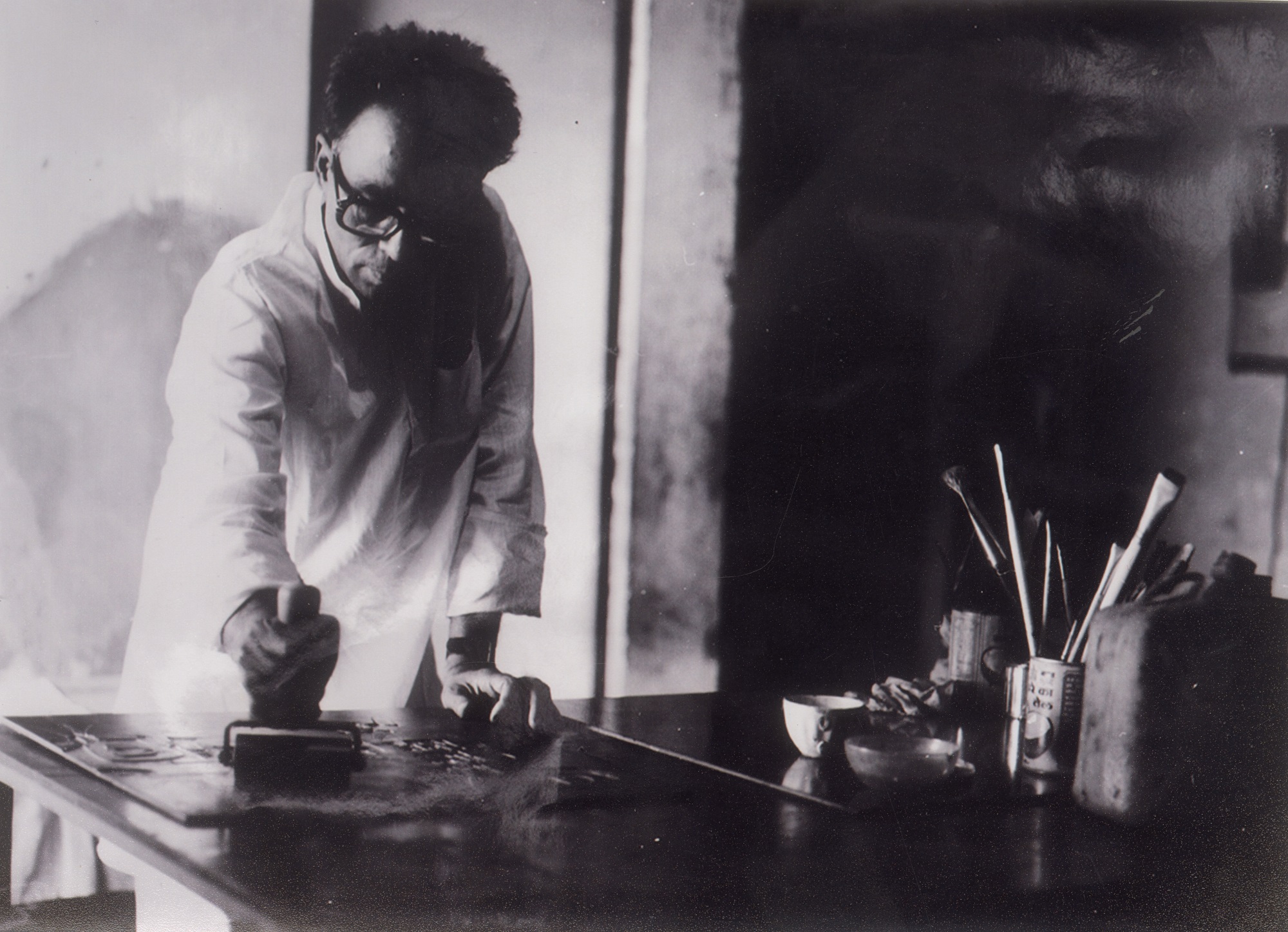

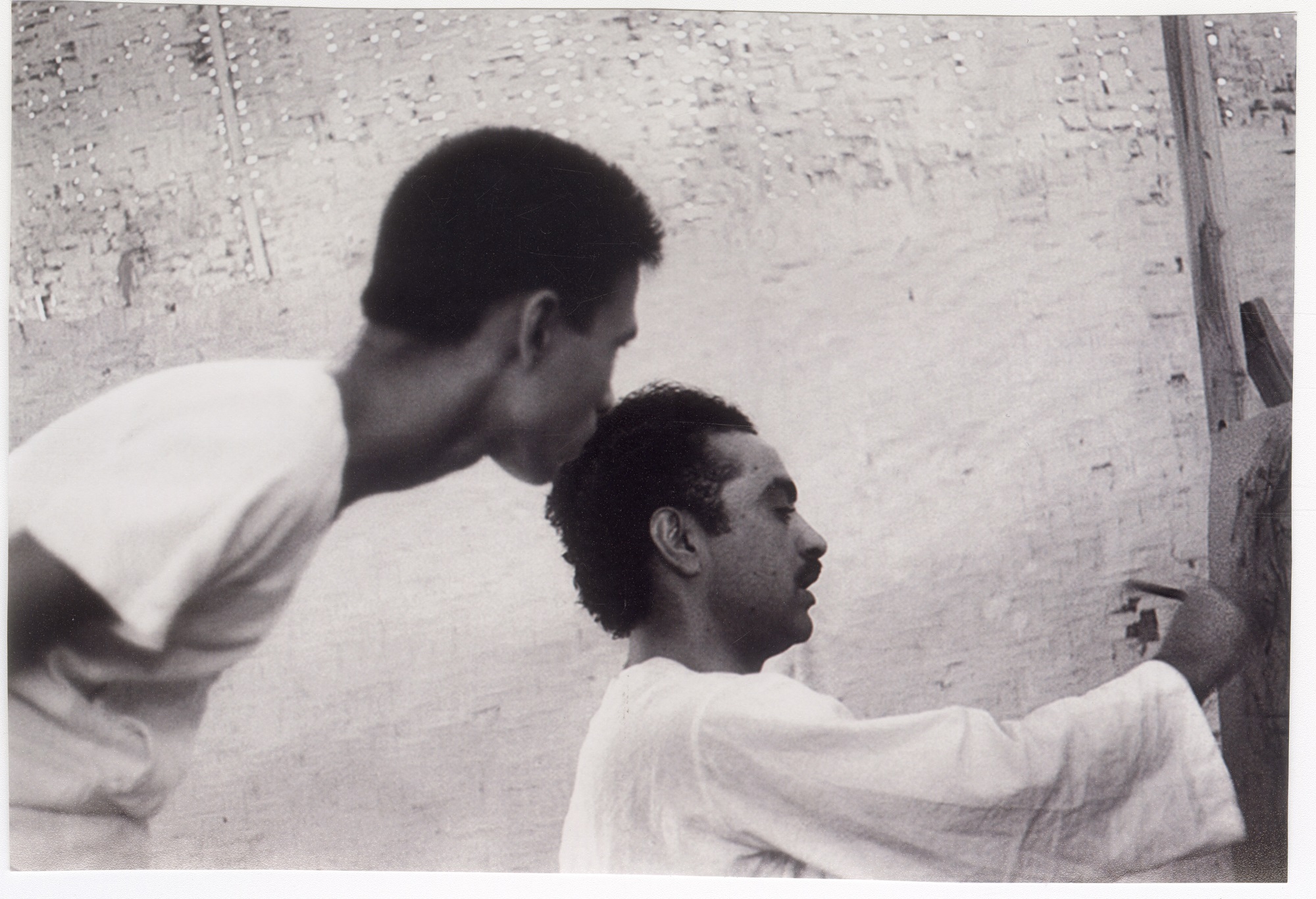

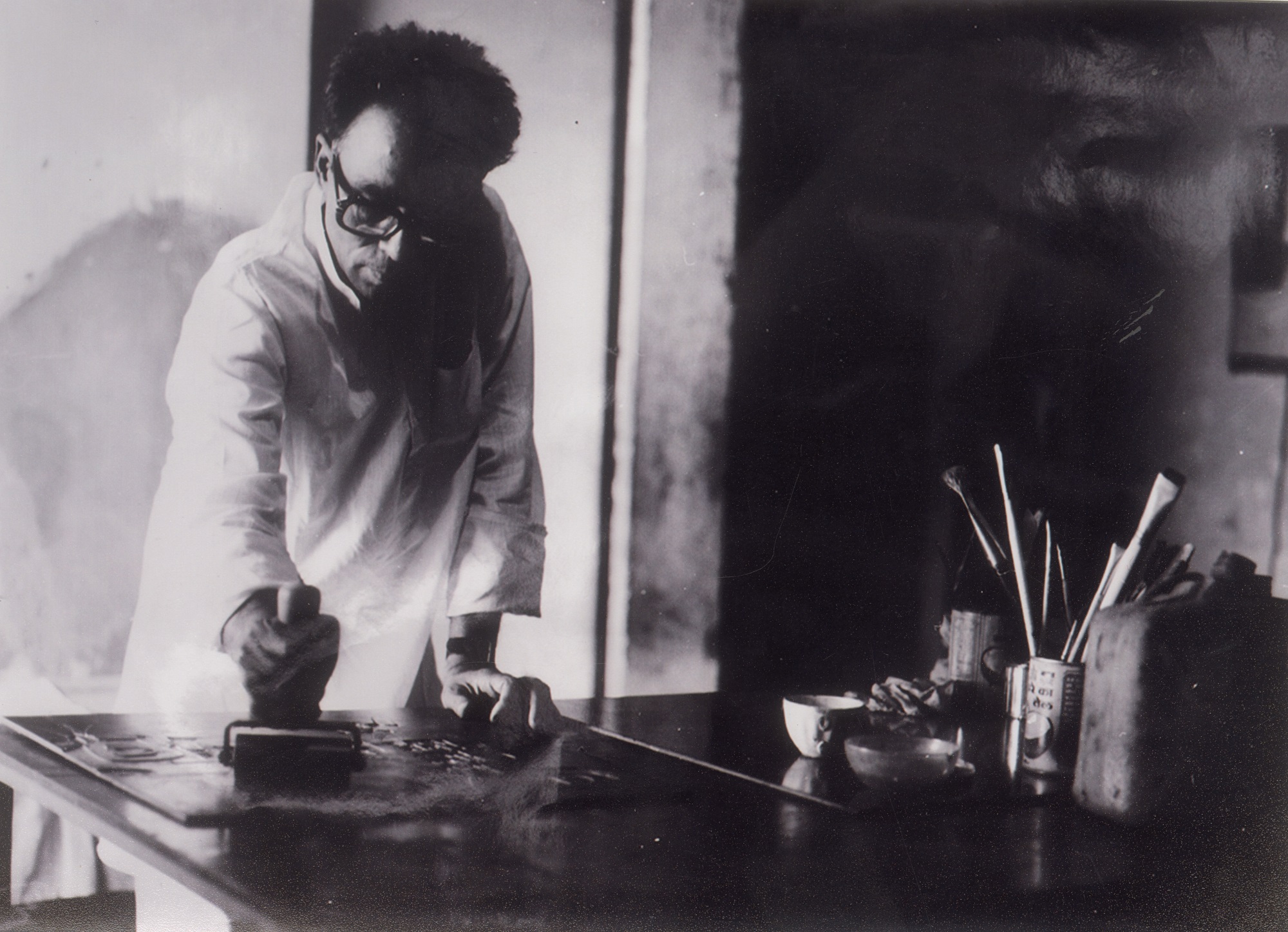

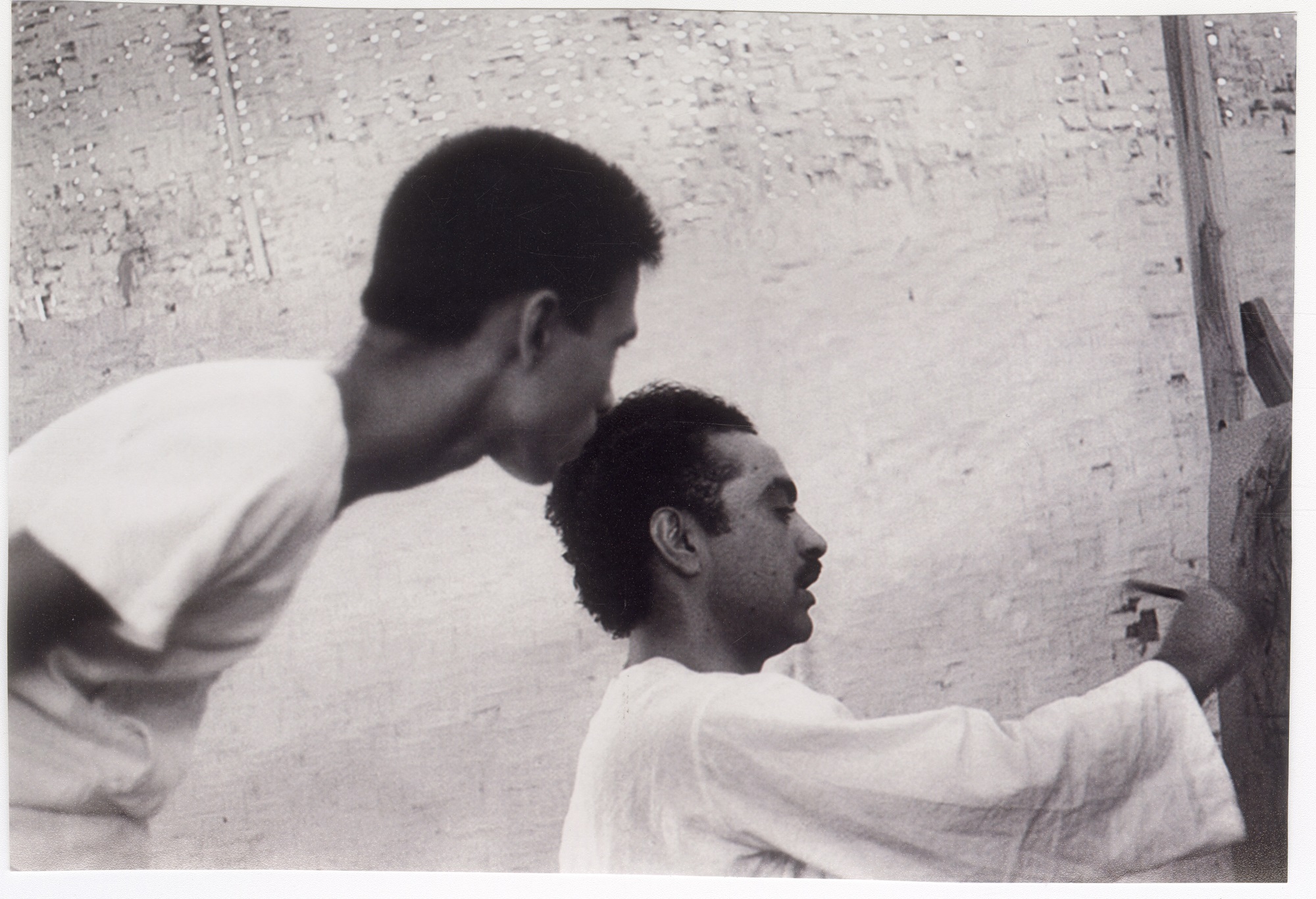

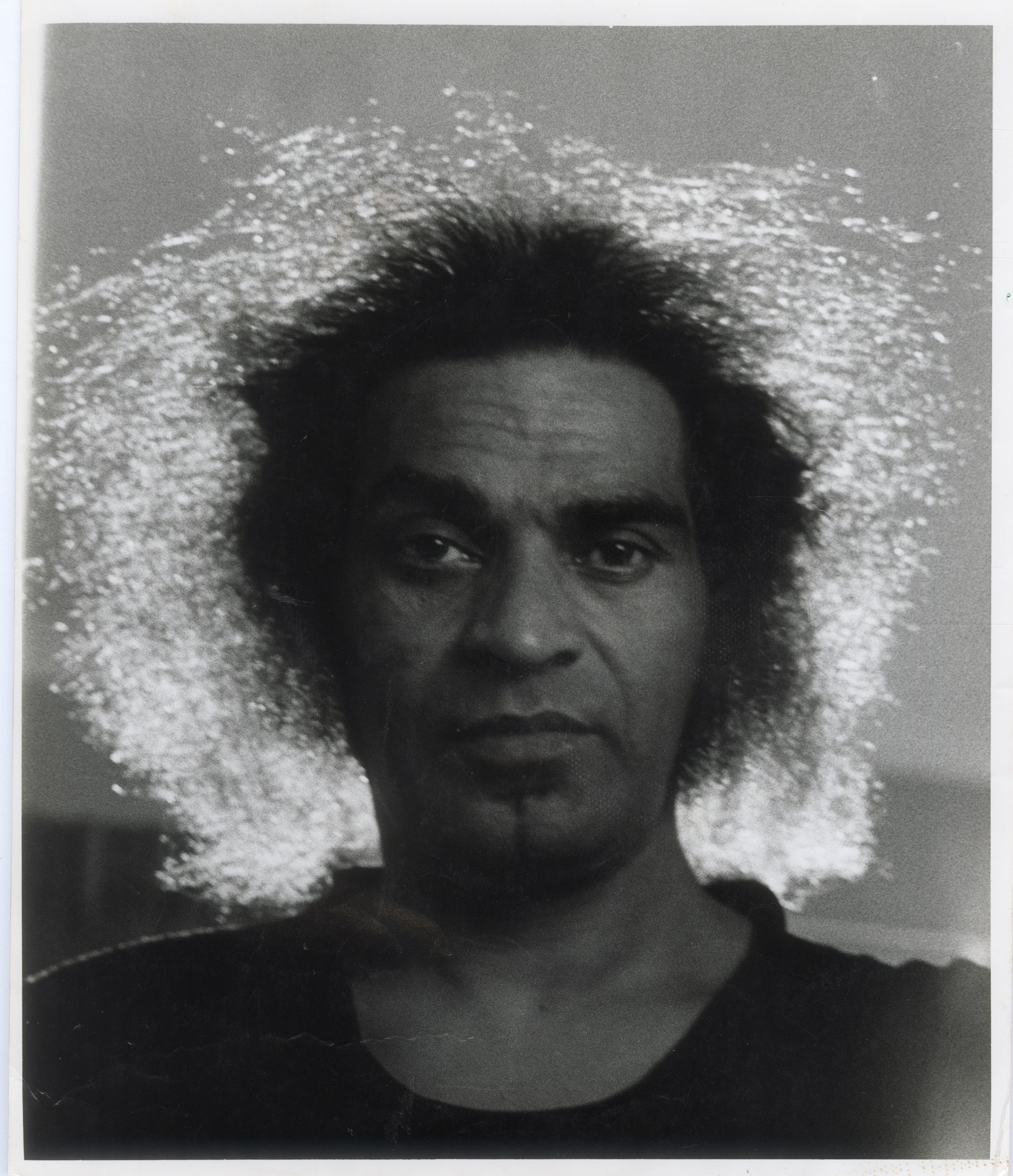

Sohan Qadri in his studio

Toronto, 1972, Digital print, 10 x 8 in.

Collection: DAG

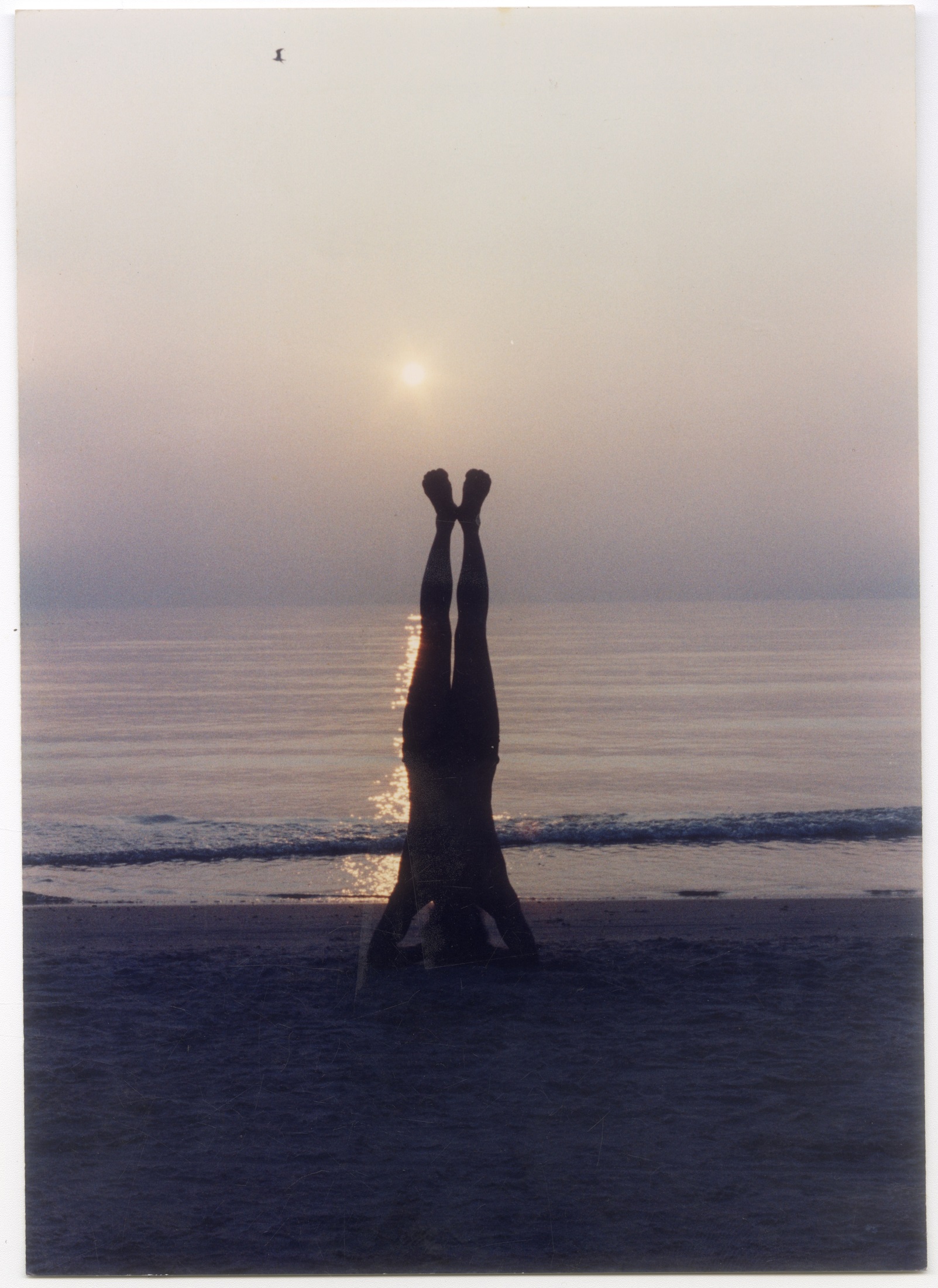

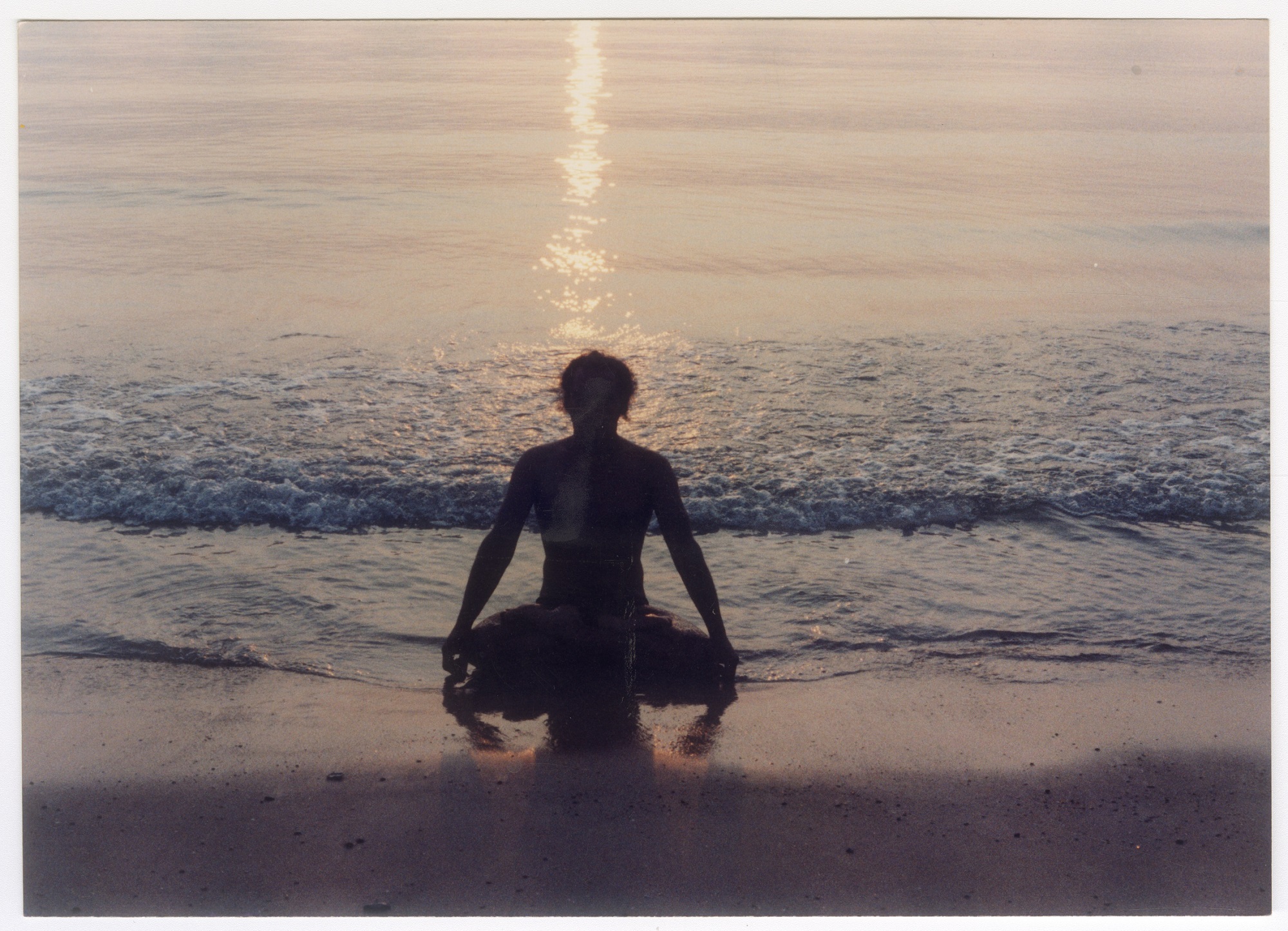

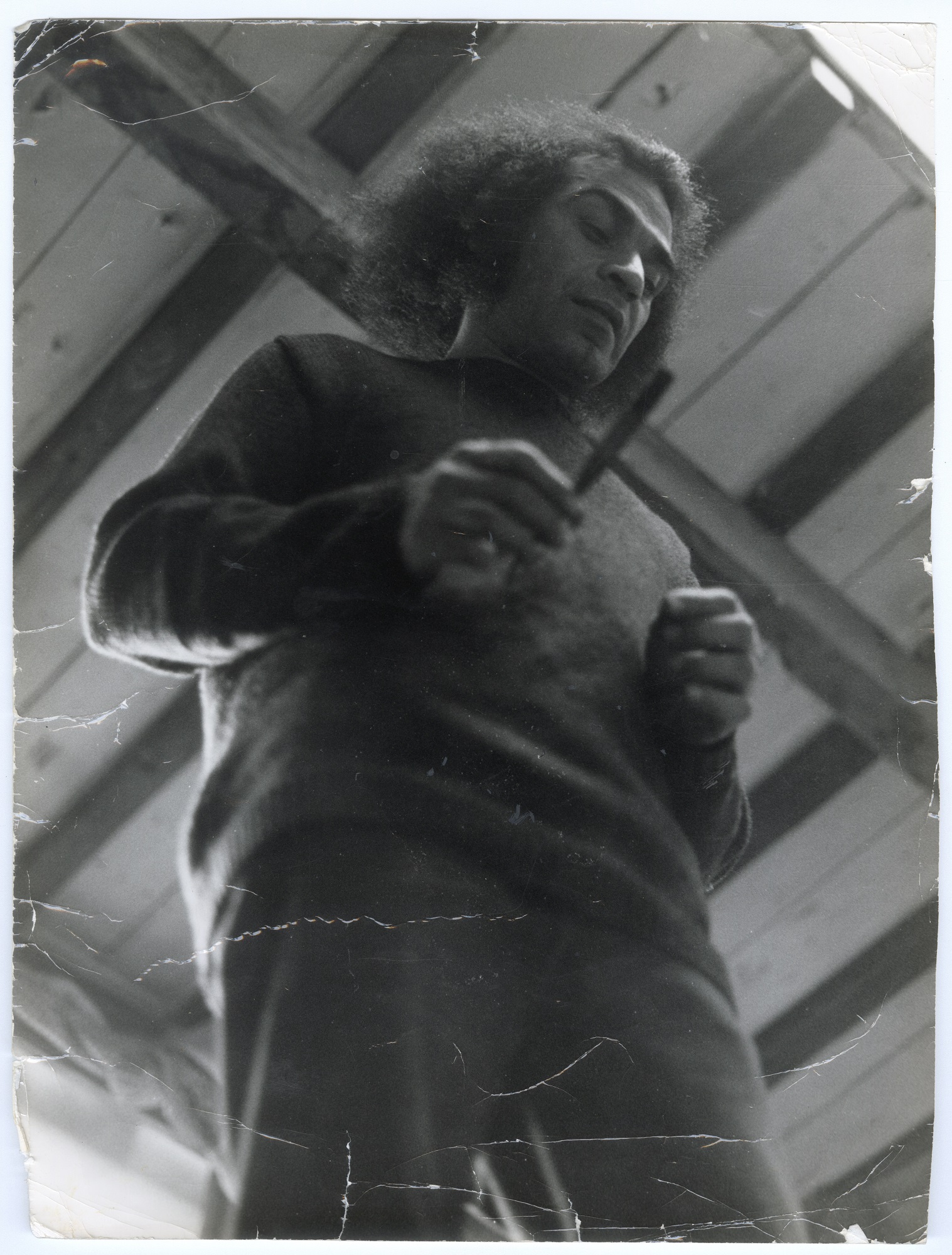

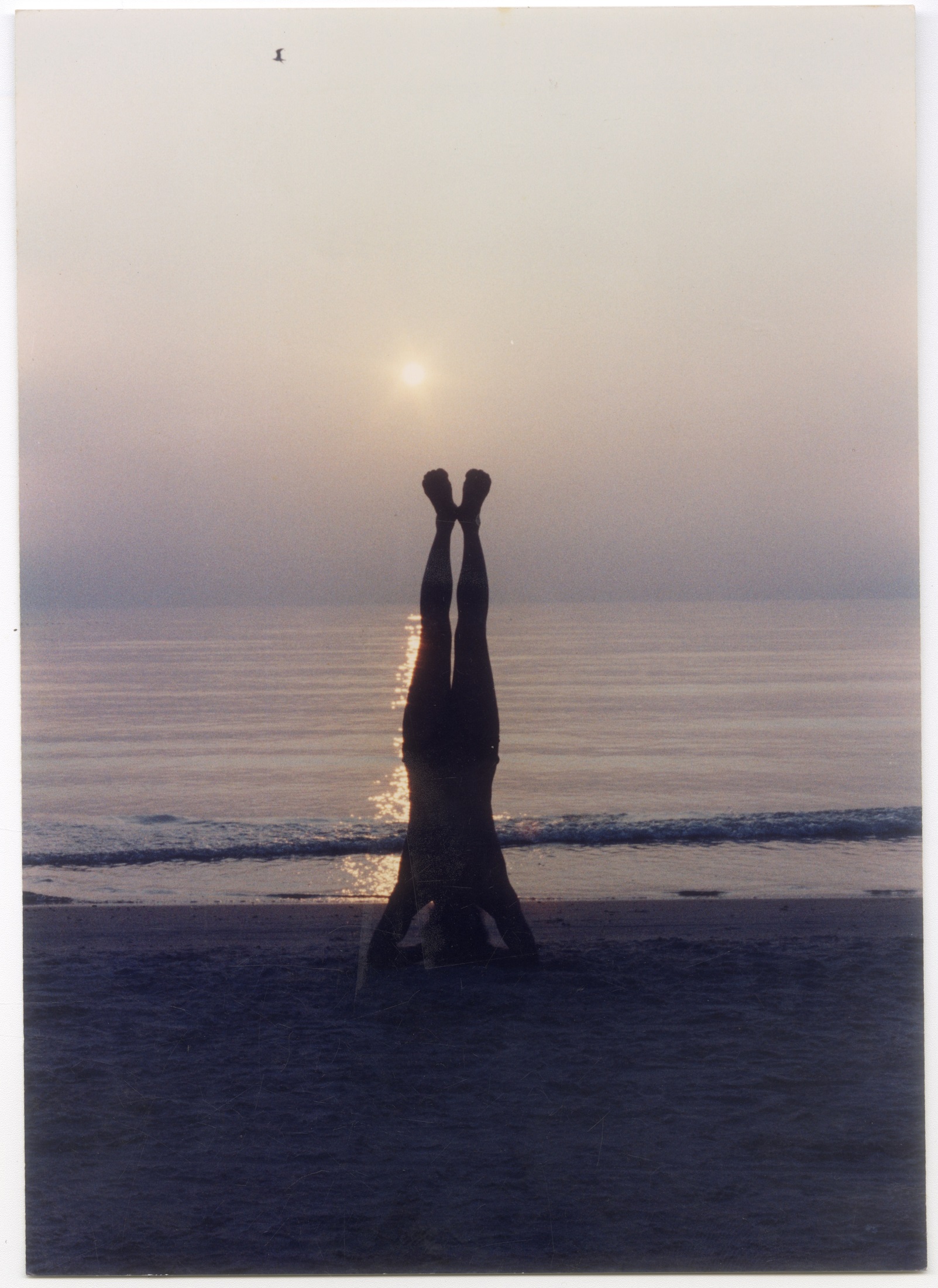

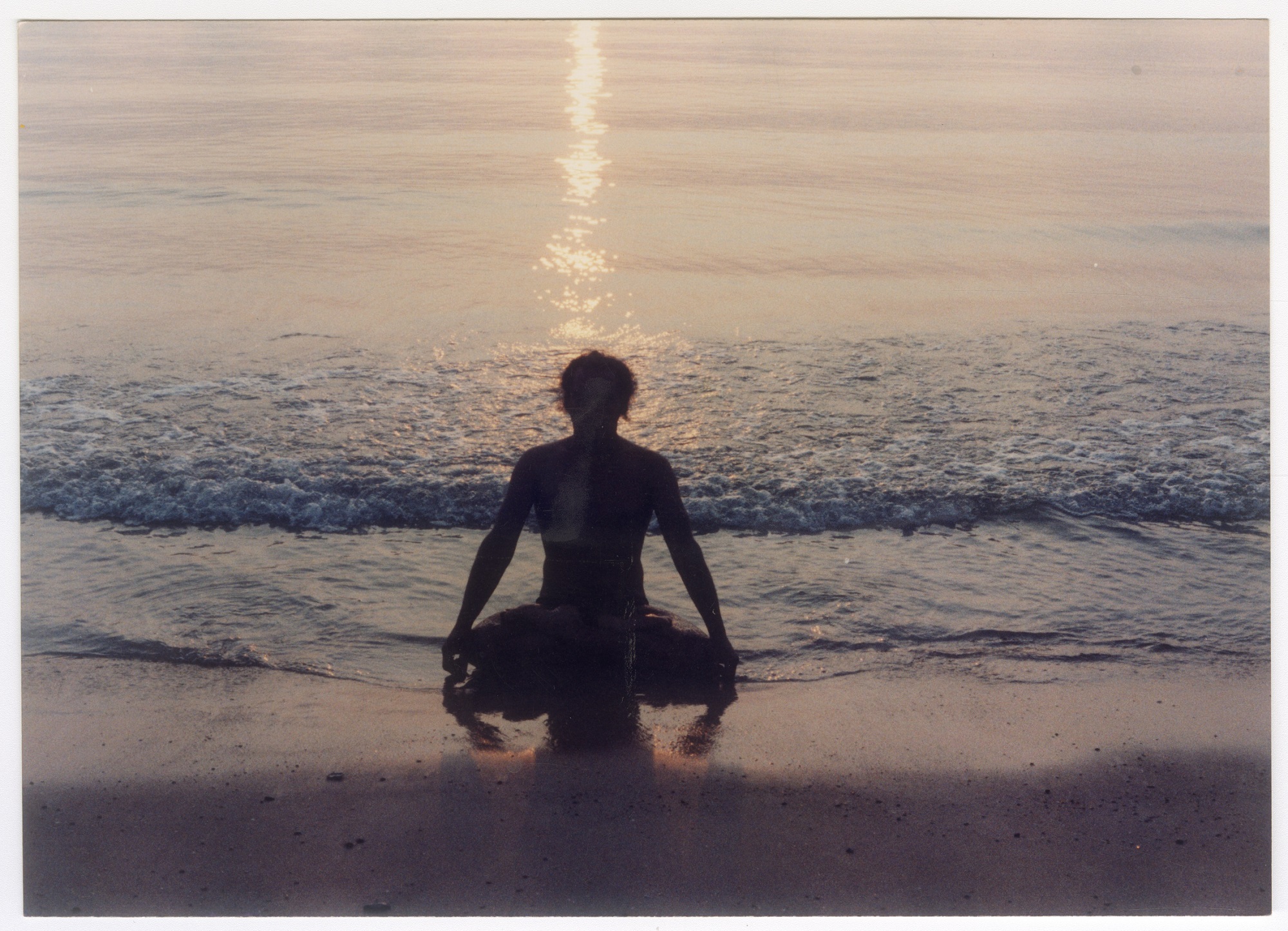

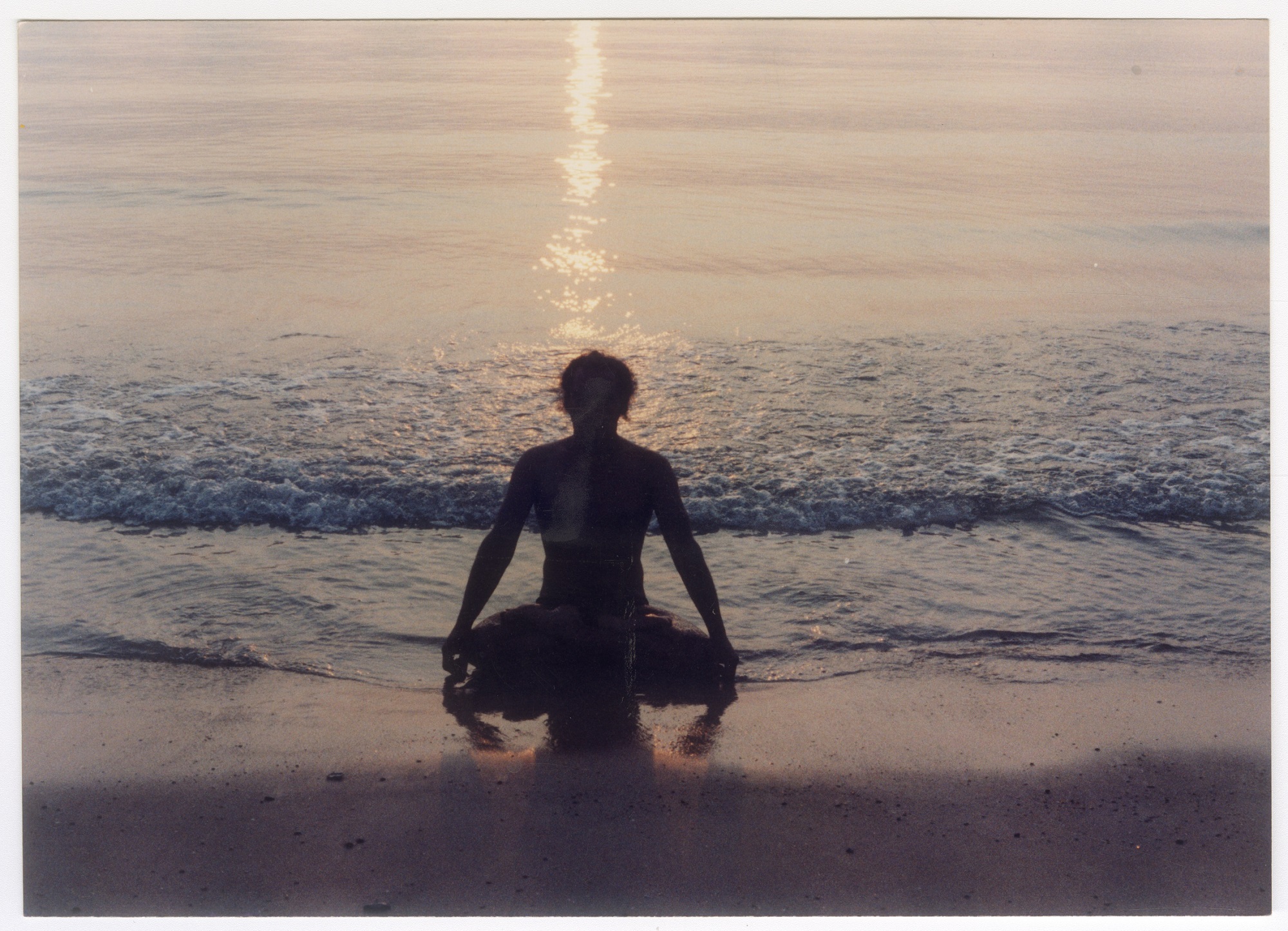

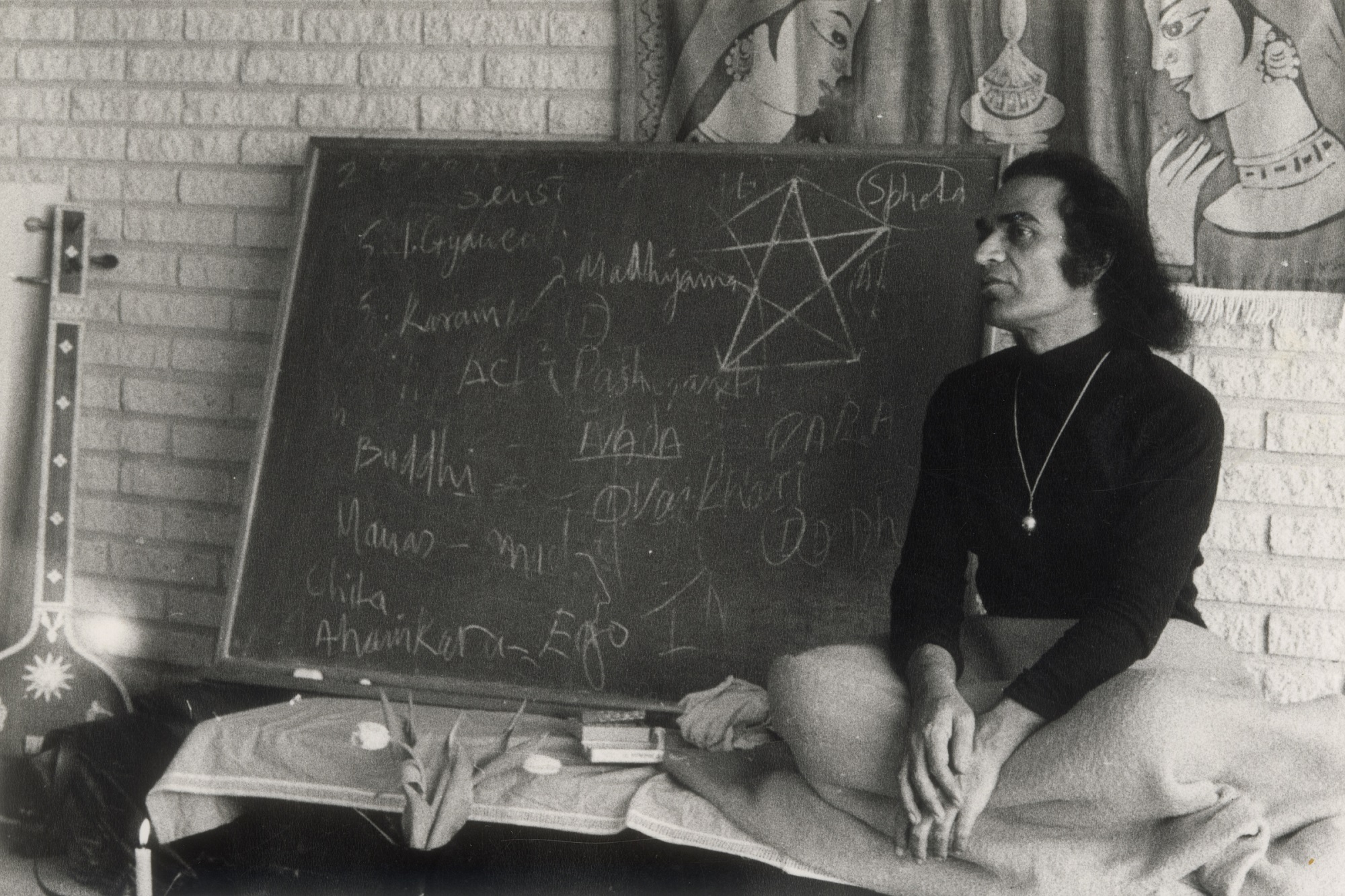

Sohan Qadri (1932 – 2011)Sohan Qadri was a painter, an avowed Tantric Vajrayana-Buddhist, Yoga practitioner and a poet, and not necessarily in that same order. Although we are concerned here mainly with Qadri’s paintings, it was one of his many ways of exploring major metaphysical themes like life, death, consciousness, self, Sunyata (as understood in Buddhism), and the non-dual nature of our existence within the vast cosmos, which Qadri poetically called the ‘dot’. His oeuvre is diverse and meditative in its essence. In this story we will explore how each of the mediums of expression adopted by Qadri—whether painting, poetry, or Tantric-Yogic practices—mutually constitute one another. Indeed, one often finds the key to unravel his mysterious artworks while reading his short haiku-like poems; similarly, the peace he attained in yogic meditation can find a direct translation in his painterly vocabulary. |

|

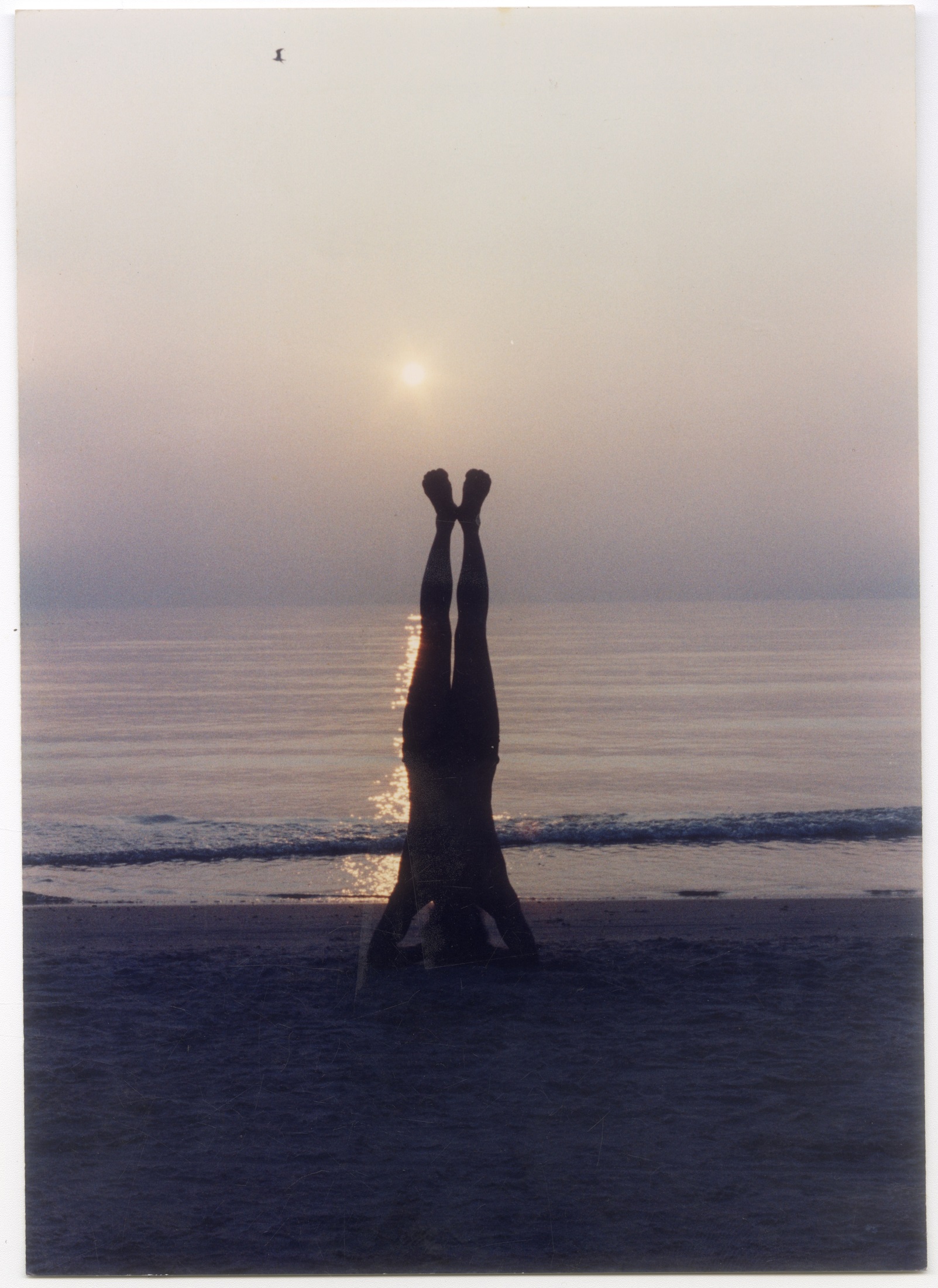

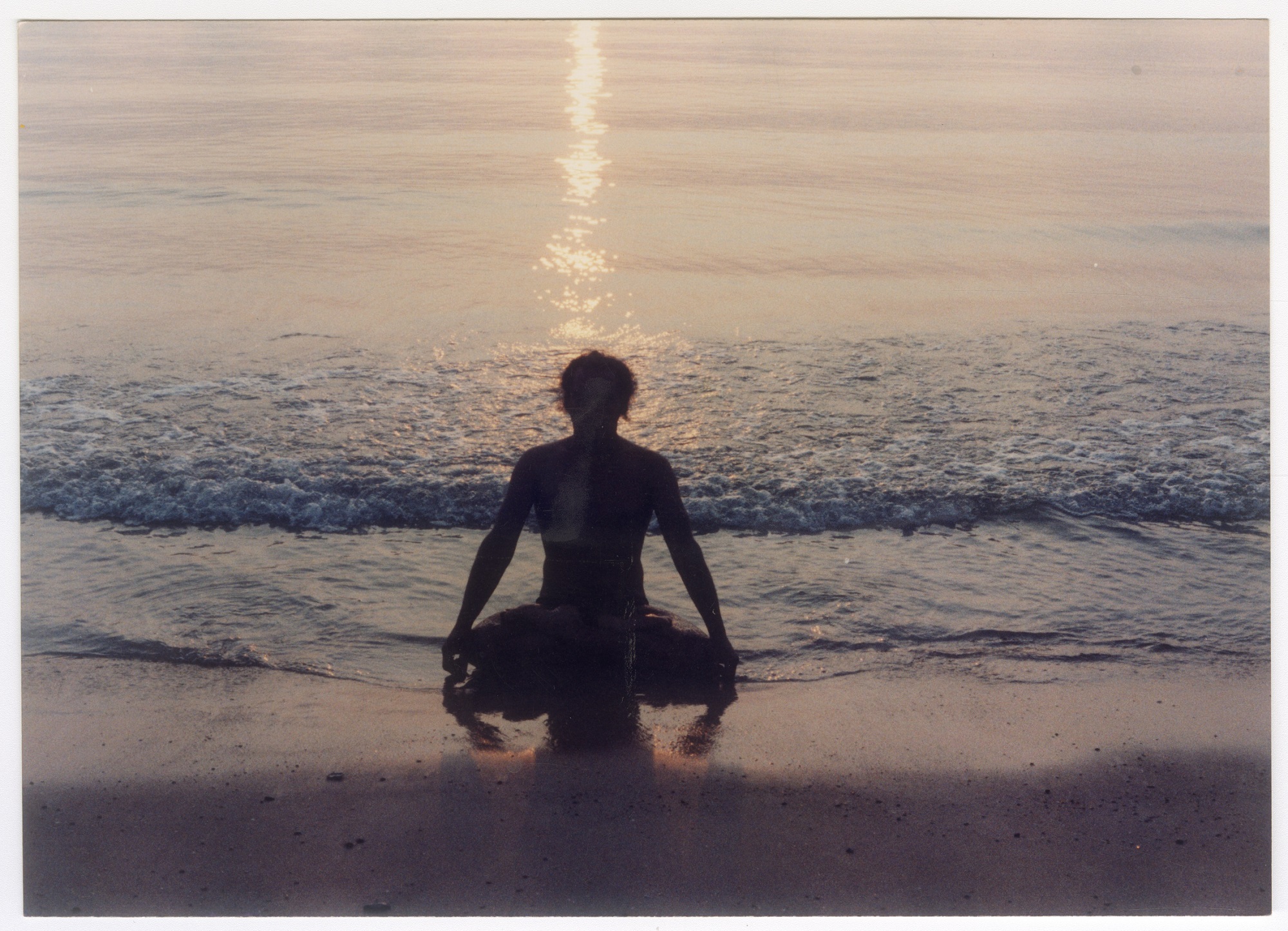

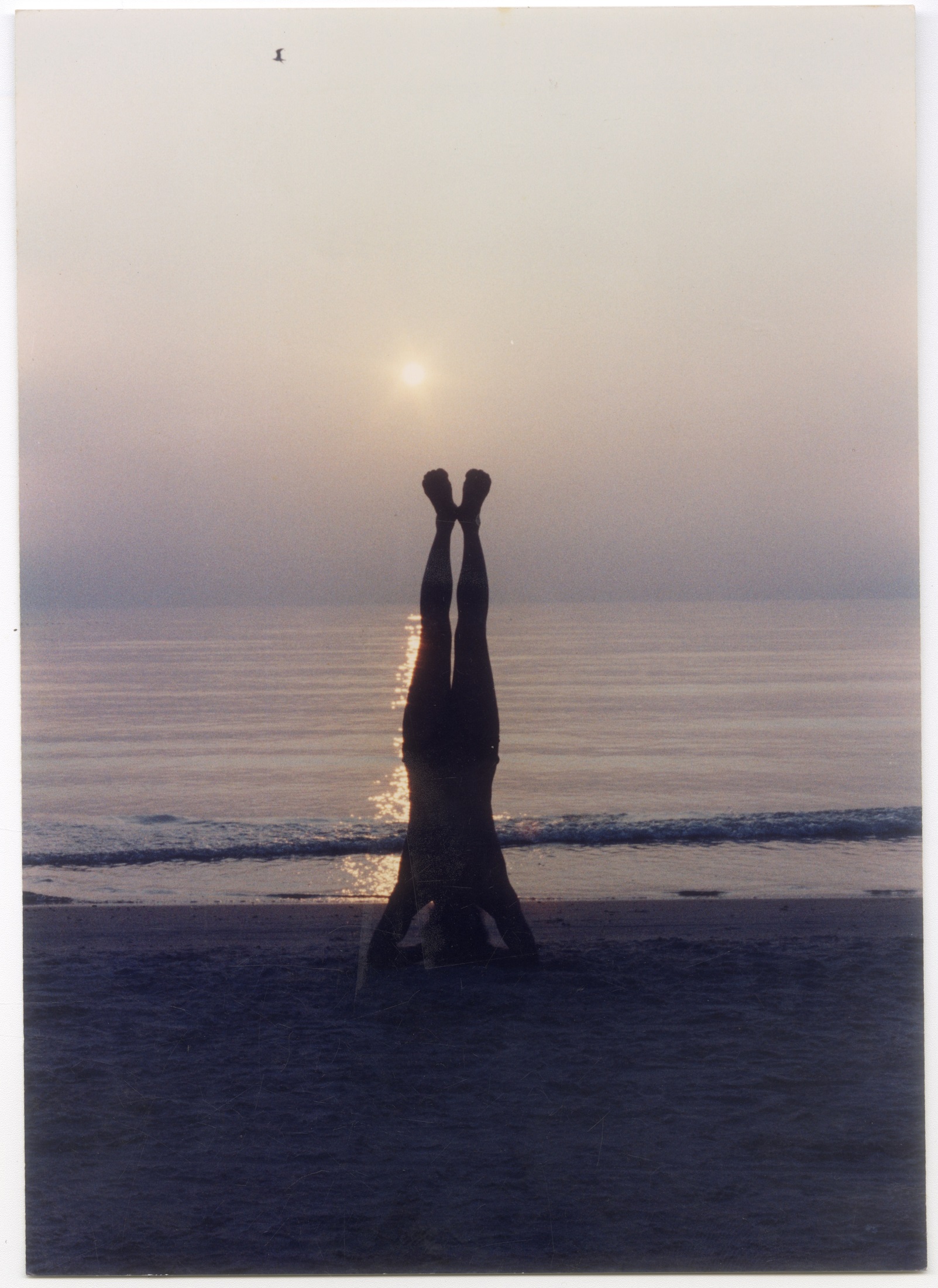

Although the process of painting would be complete in a matter of fifteen minutes, the artist required a longer period to prepare himself before setting out to paint, by emptying his mind of all the other distractions. This process resembles the Yoga meditation where one is invited to slowly withdraw their mind from other preoccupations so as to fully sense the body’s flow of spiritual energy. Indeed, Qadri would not leave a mark on the paper until ‘waves of energy (were) always centred on one focal point.’ And in turn, the artist expected the same spirit to be at work in the viewer’s mind, so he said, 'To view [my paintings in ink and dye] successfully, one must lose one’s frame of reference and look at the picture with a fresh eye.' |

|

|

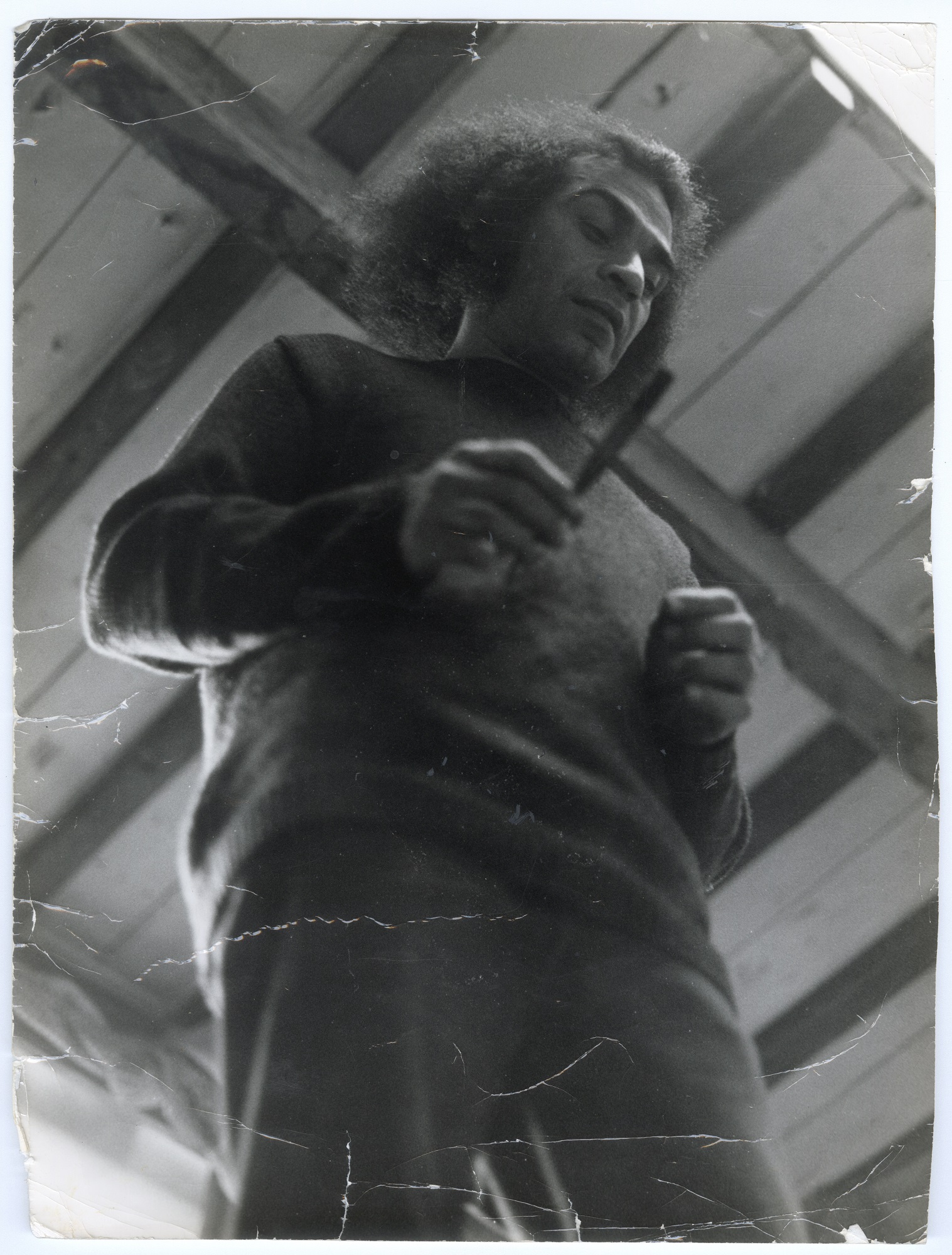

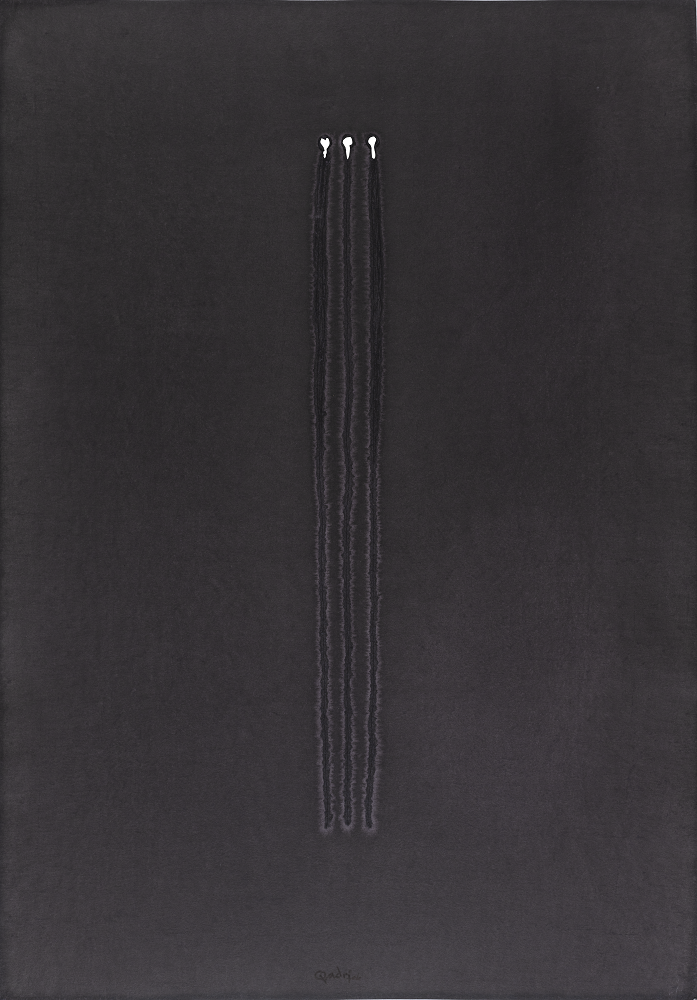

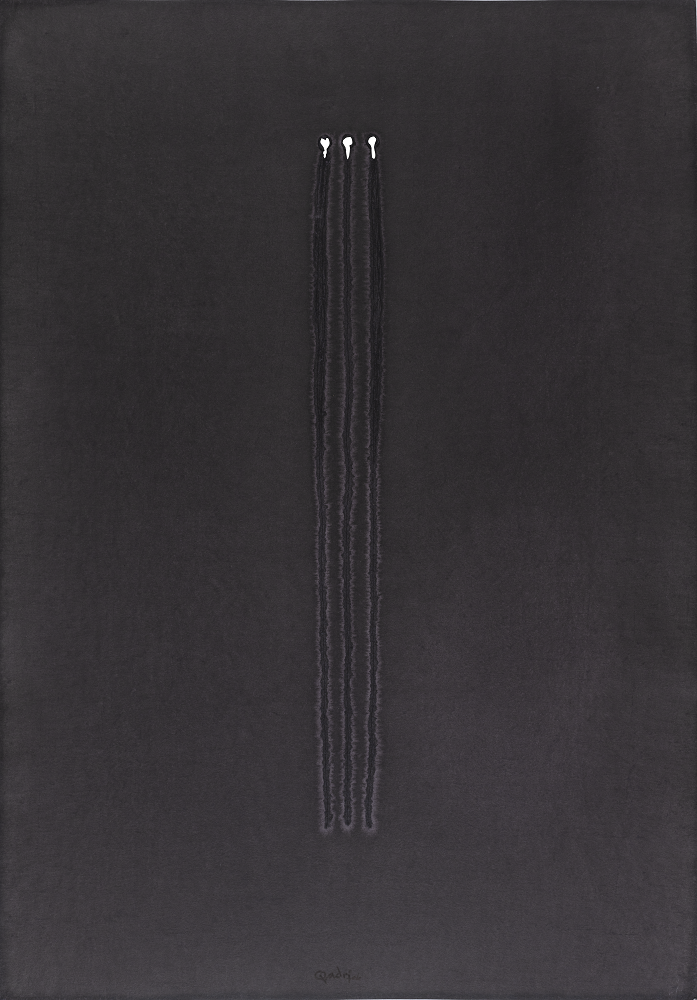

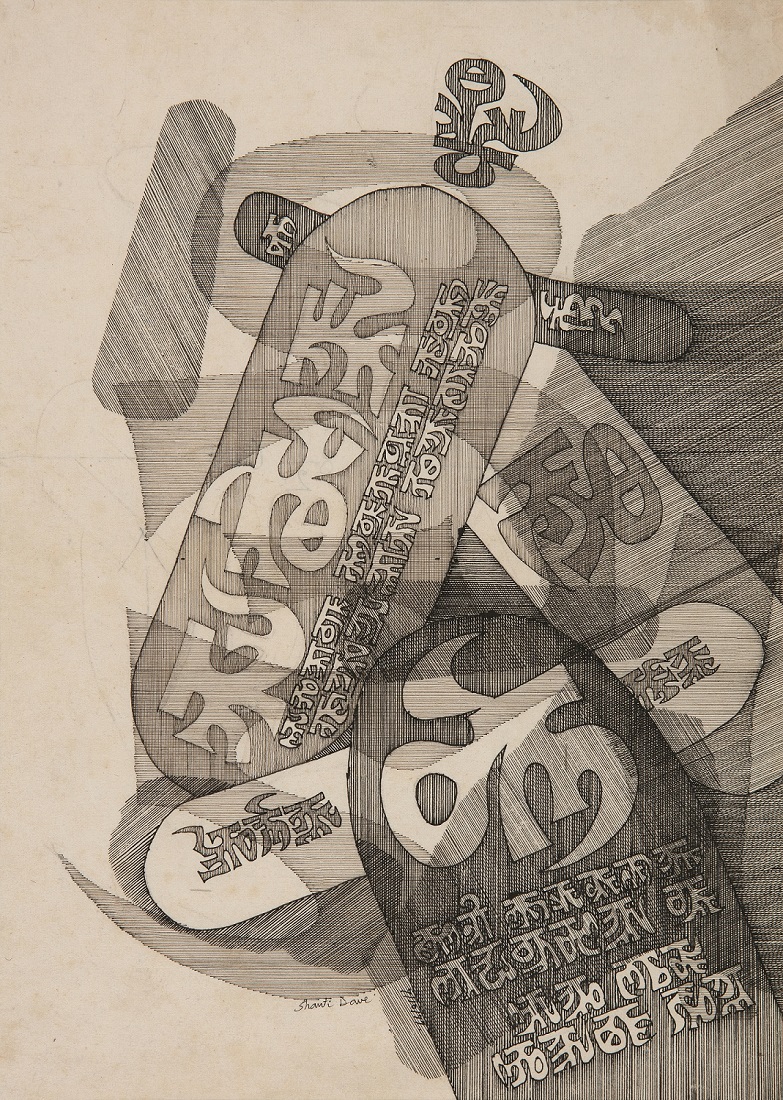

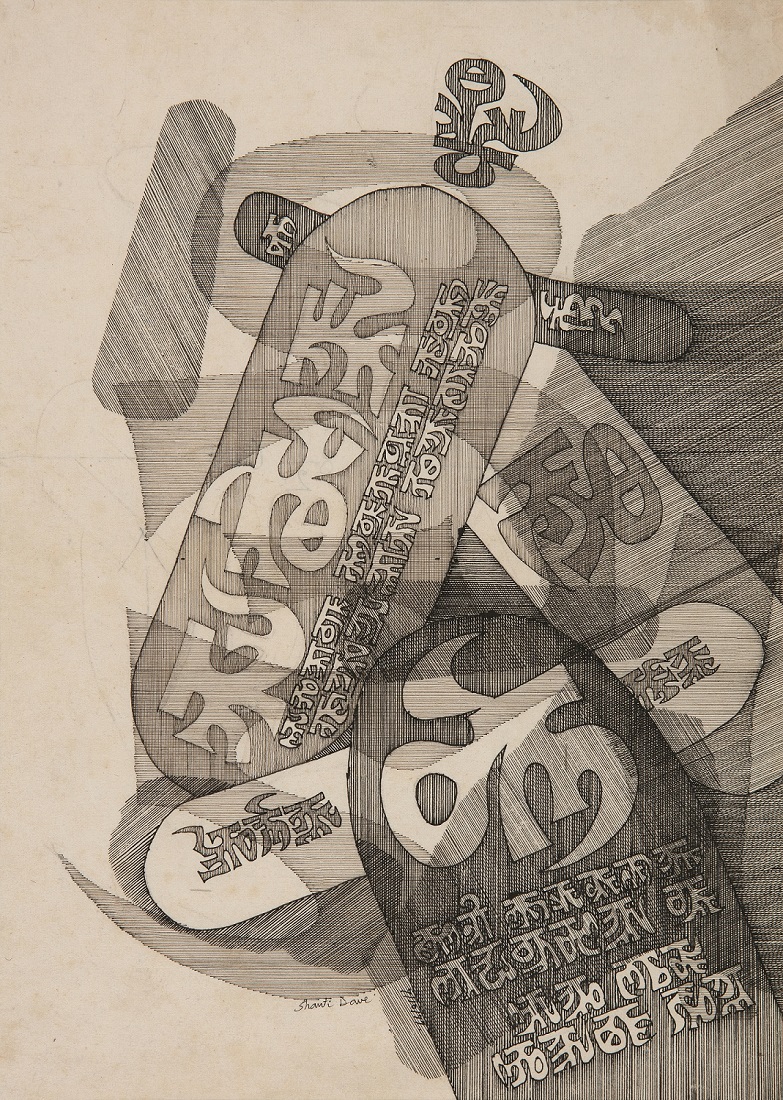

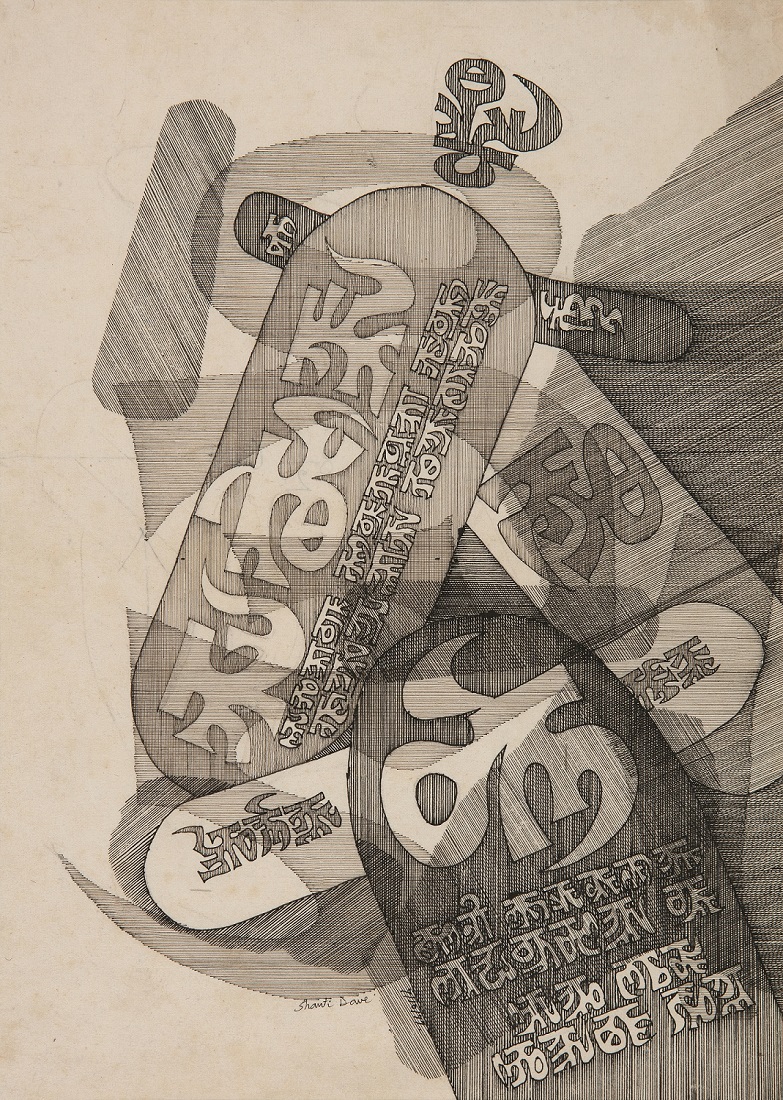

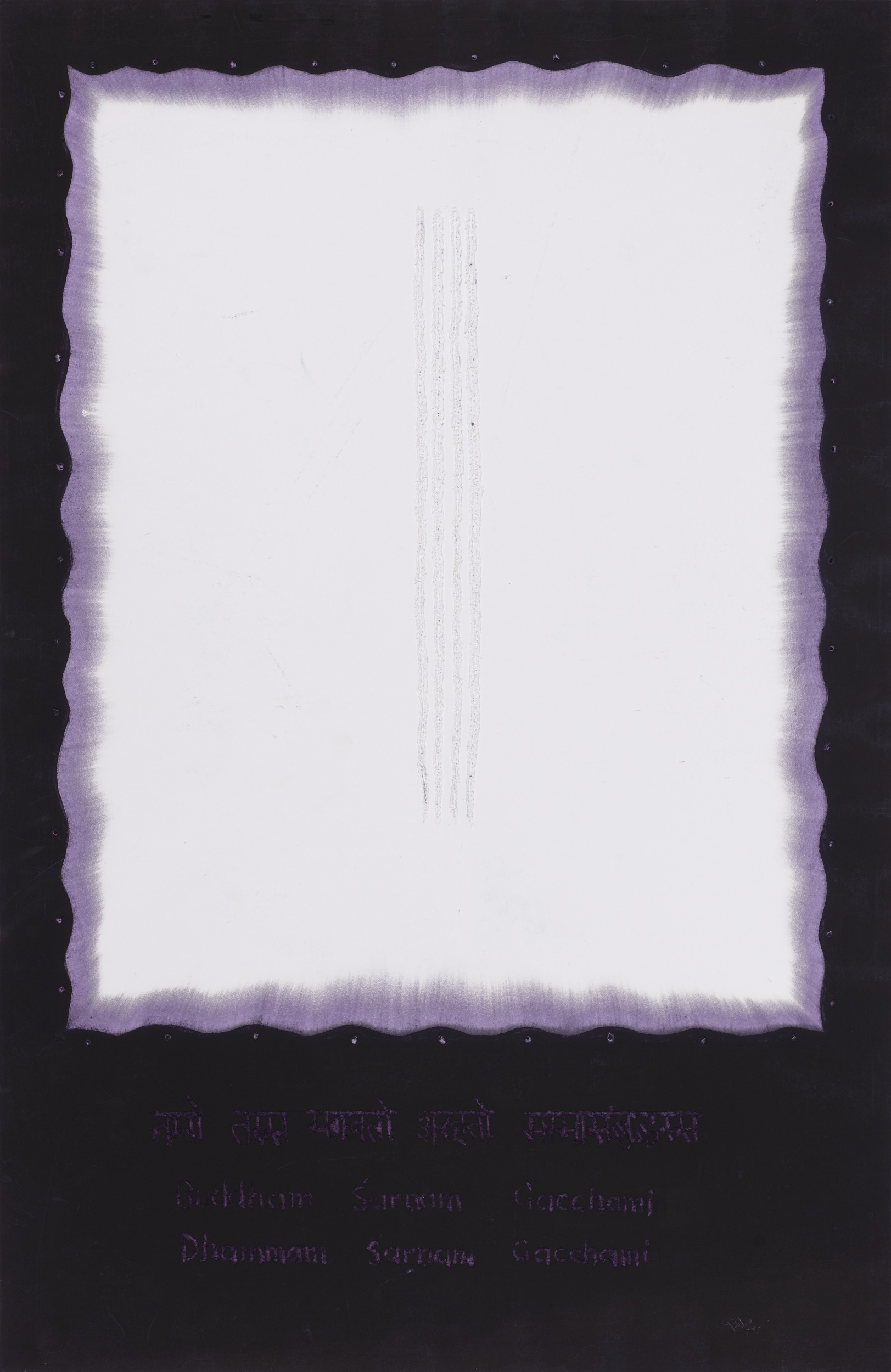

Sohan Qadri

Untitled

1995, Ink and dye on paper

Collection: DAG

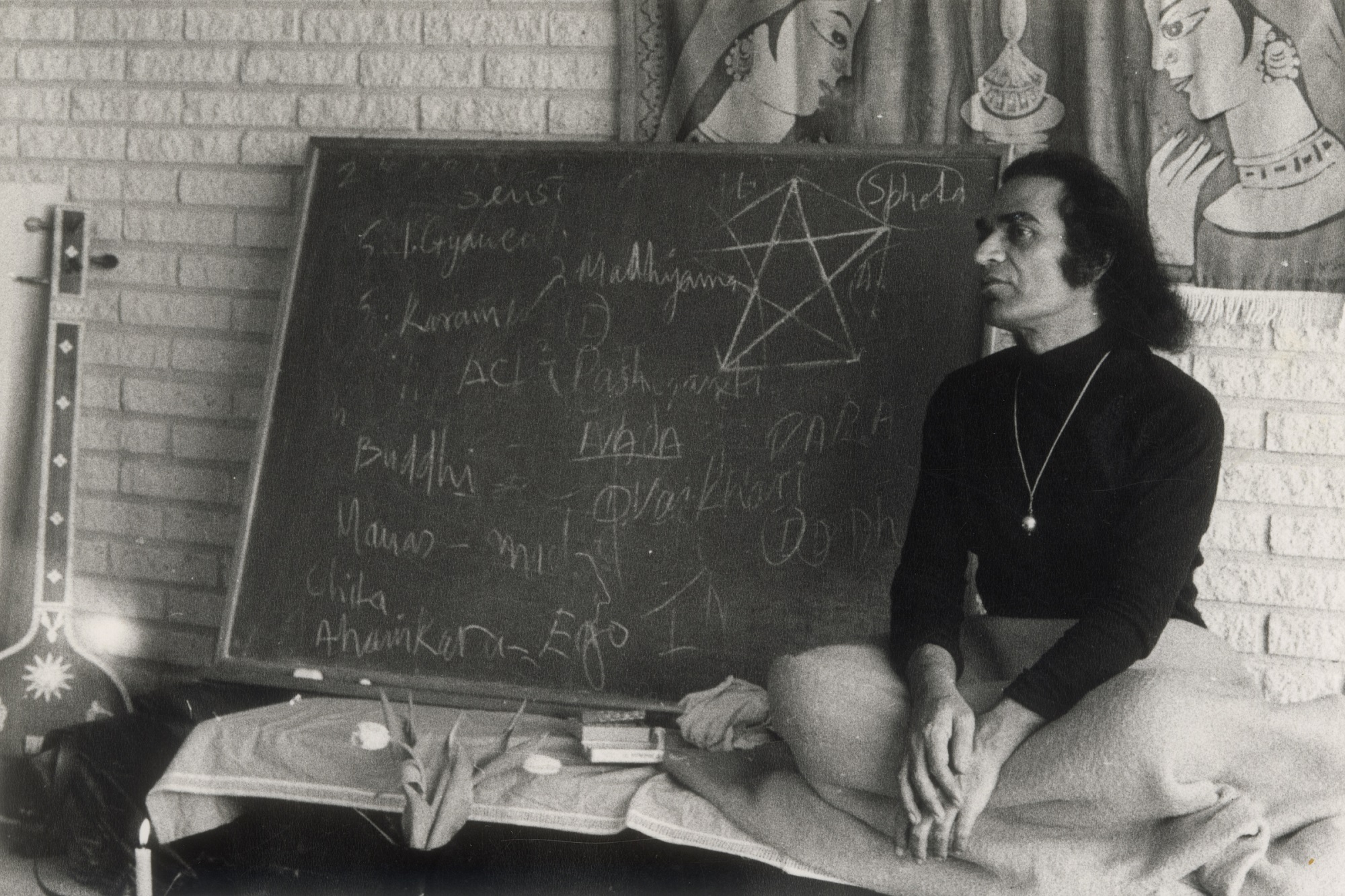

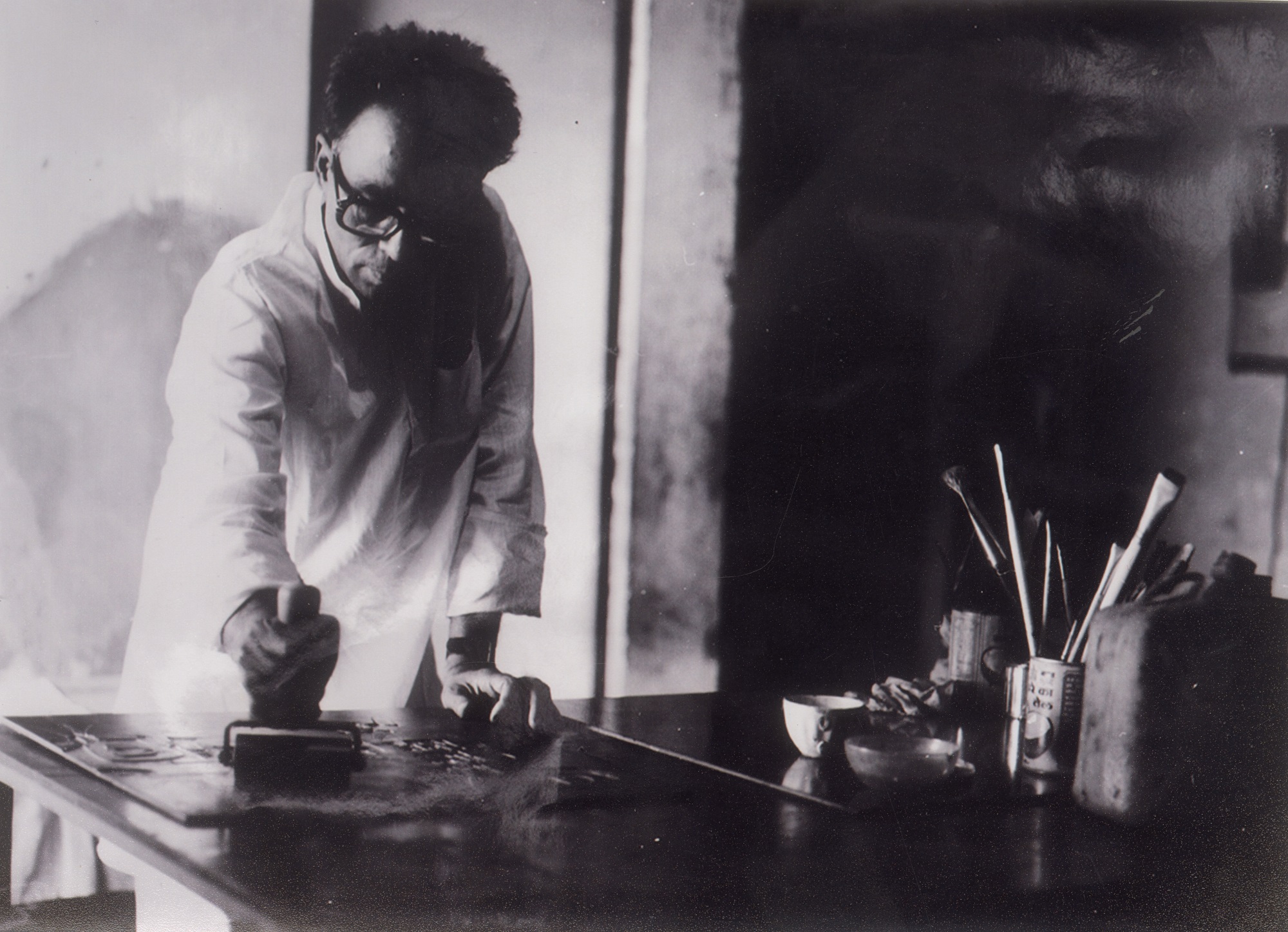

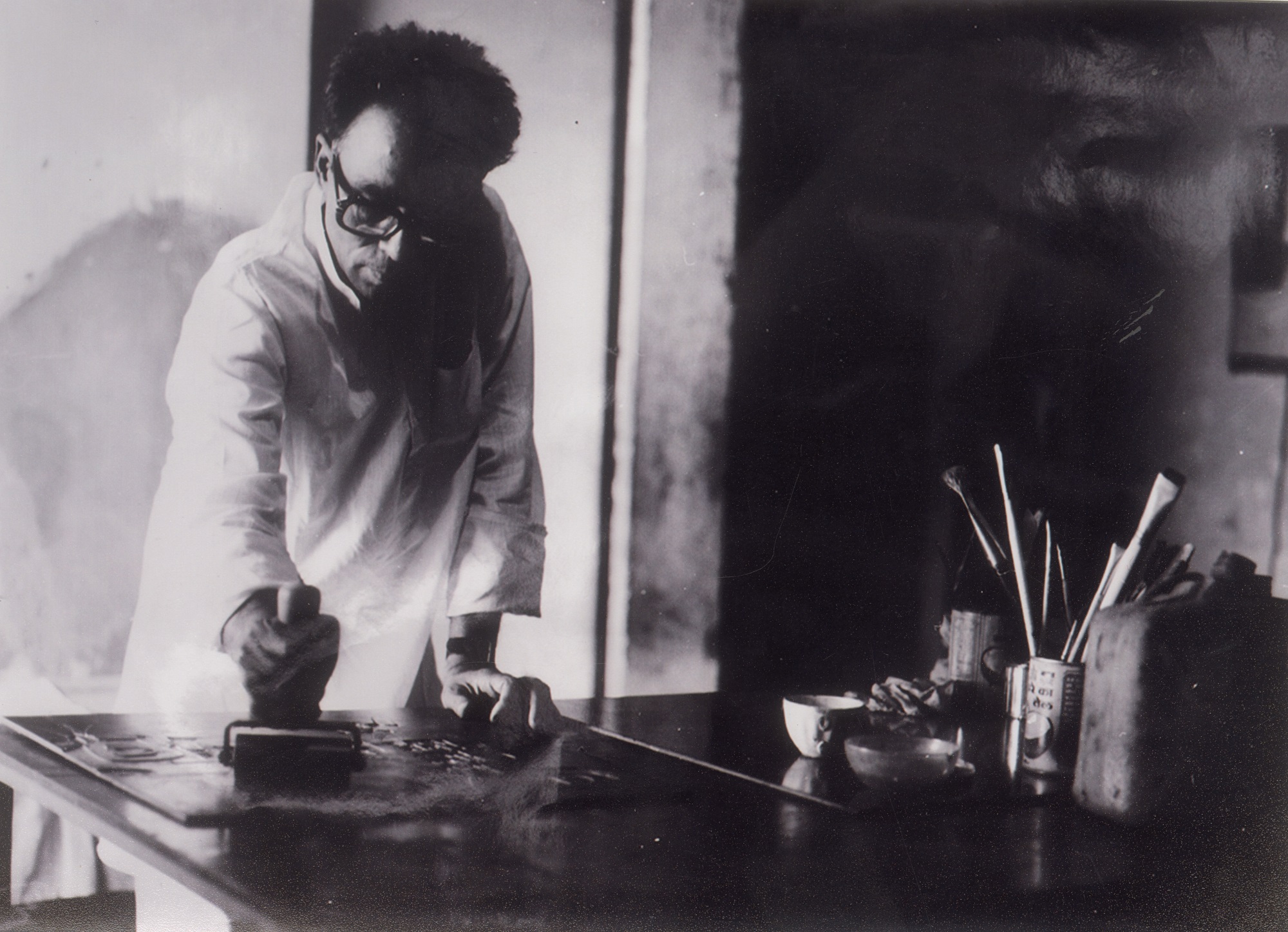

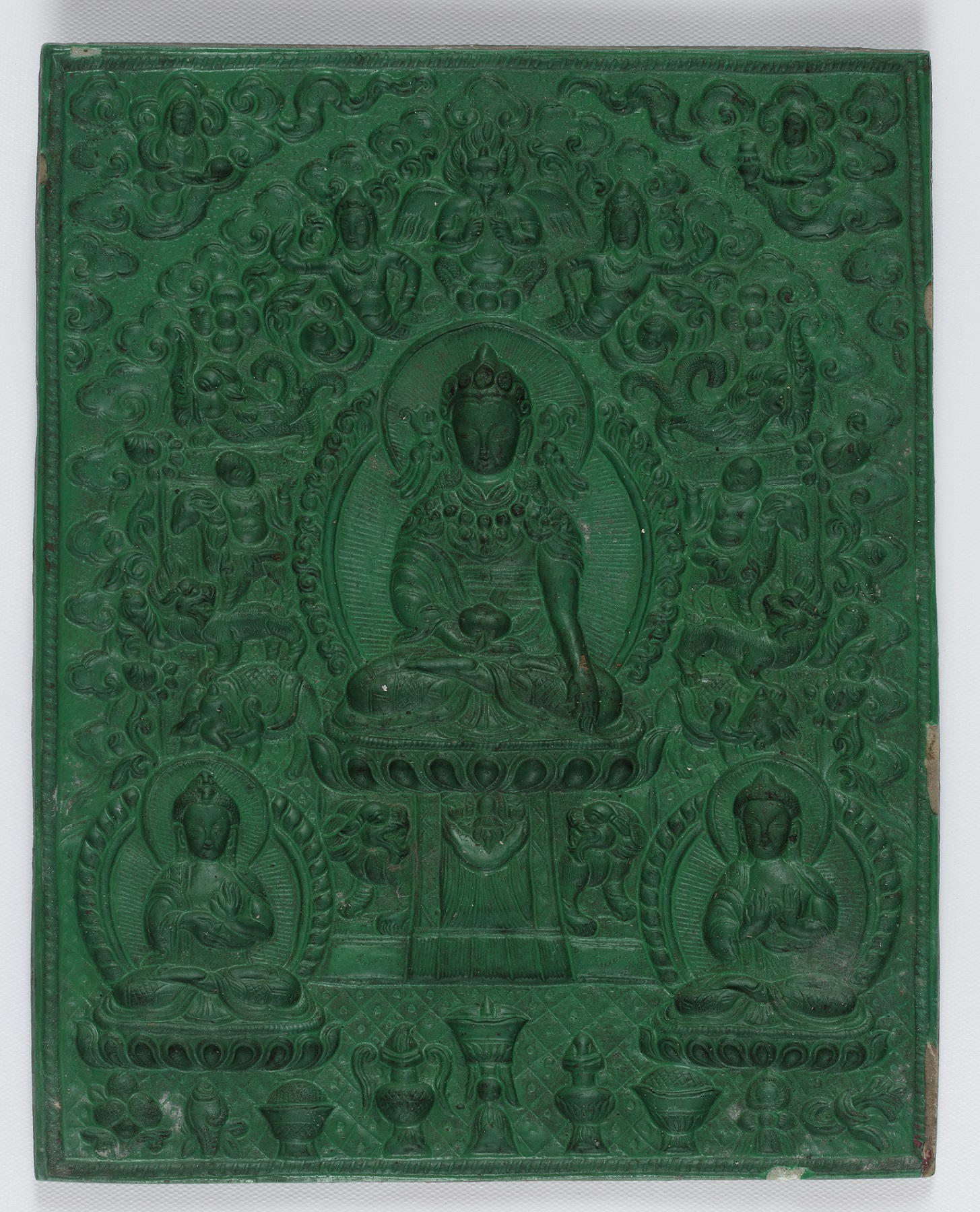

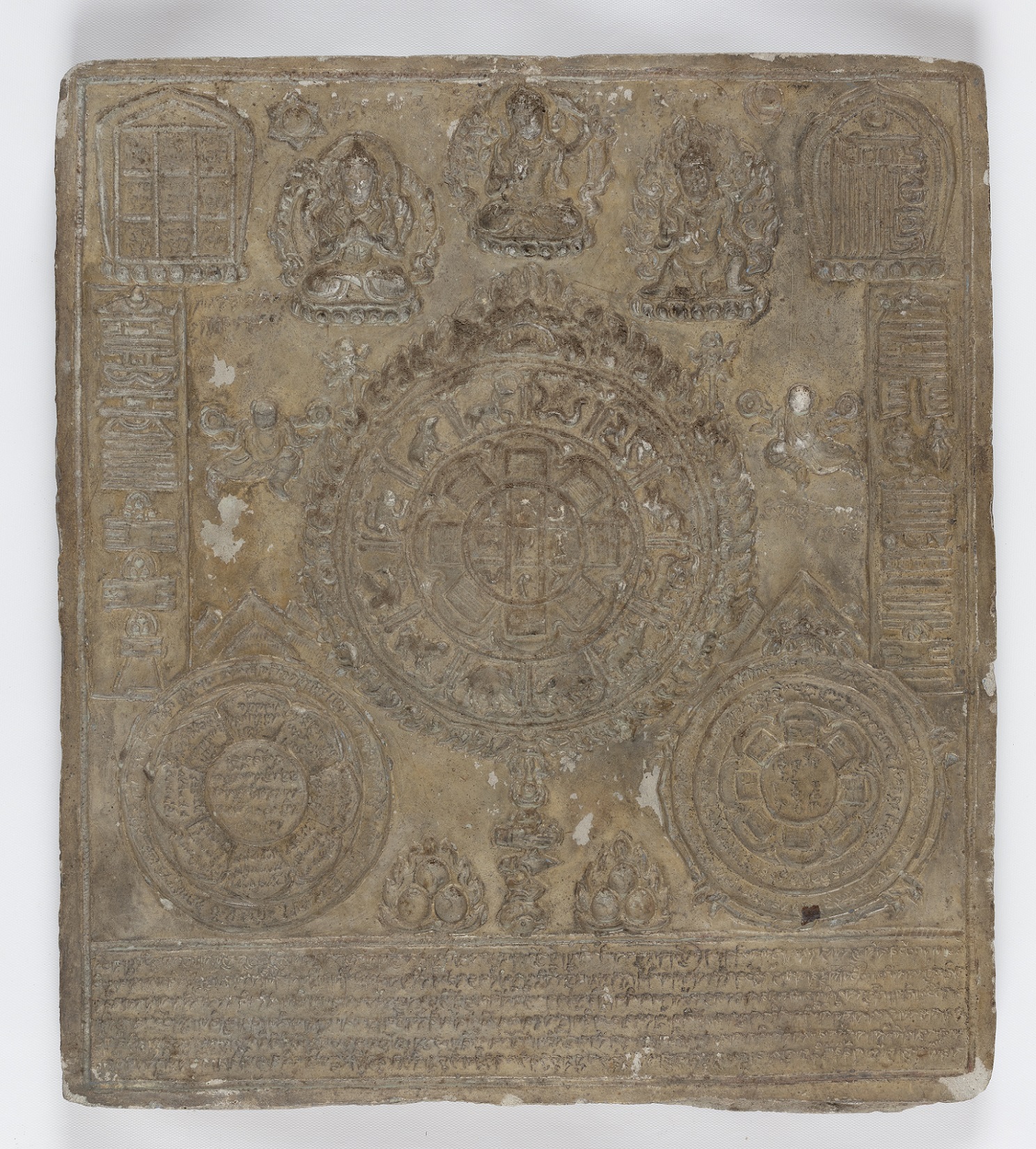

Qadri’s method consists of soaking the thick handmade paper in liquid and applying ink and dye over many stages. Since ink and dye are prone to spread over the paper, it requires the artist to not lose any control over the long process. Qadri also incised his paper repetitively to make ‘dots’; and even in his poetry, he invokes the dots over and over again. Qadri puts his method in words, giving reasons for distancing himself from the conventional medium of painting: 'Effort is superfluous… Deep states of being are not brought out by effort. Paper and ink are very soft, feminine, while canvas and oils are extremely masculine, aggressive. I don’t want to fight anymore. And with inks and dyes, I do not have to. Here there is no brush stroke, no painter. The aura of the form is the painting.' |

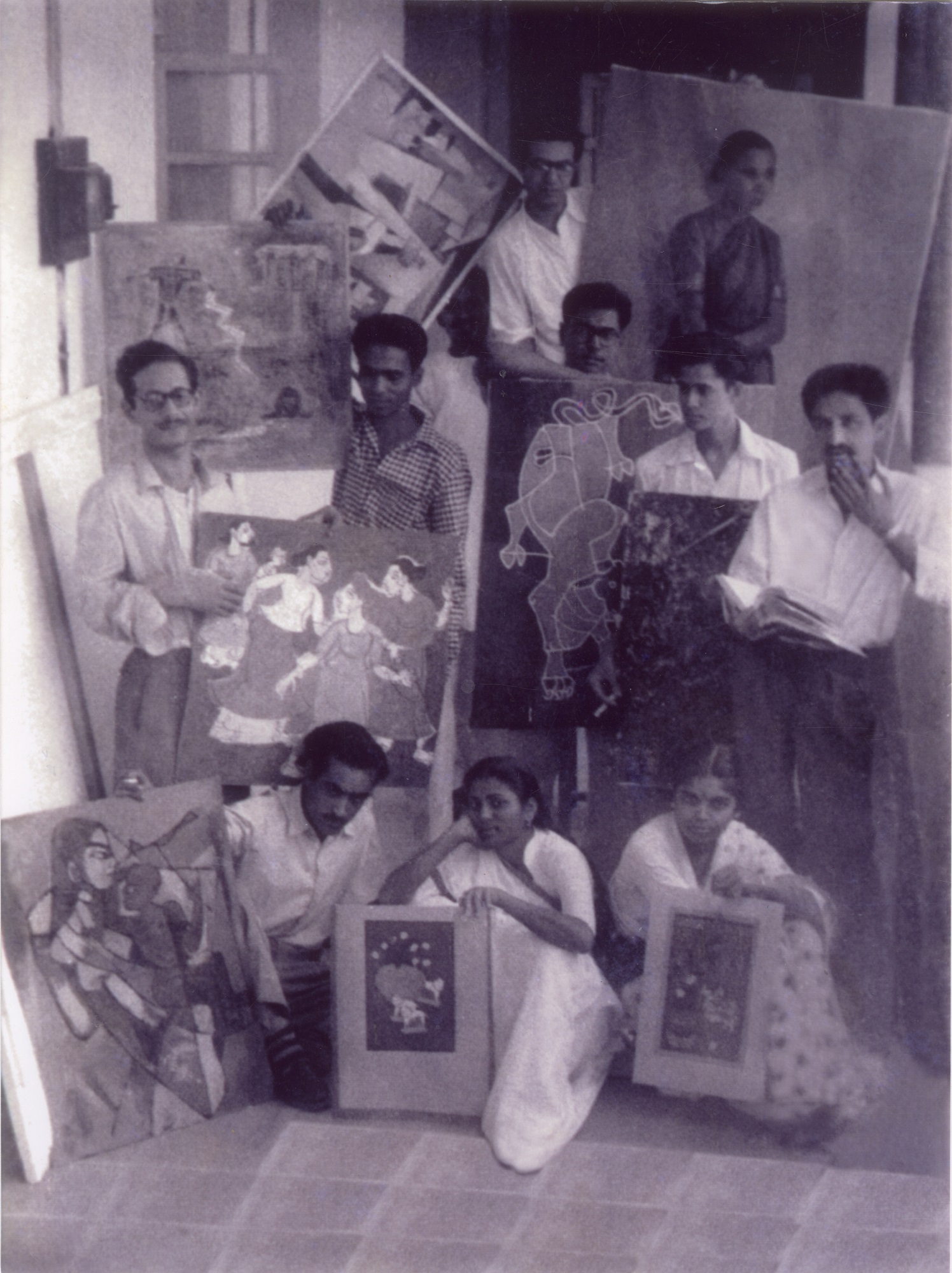

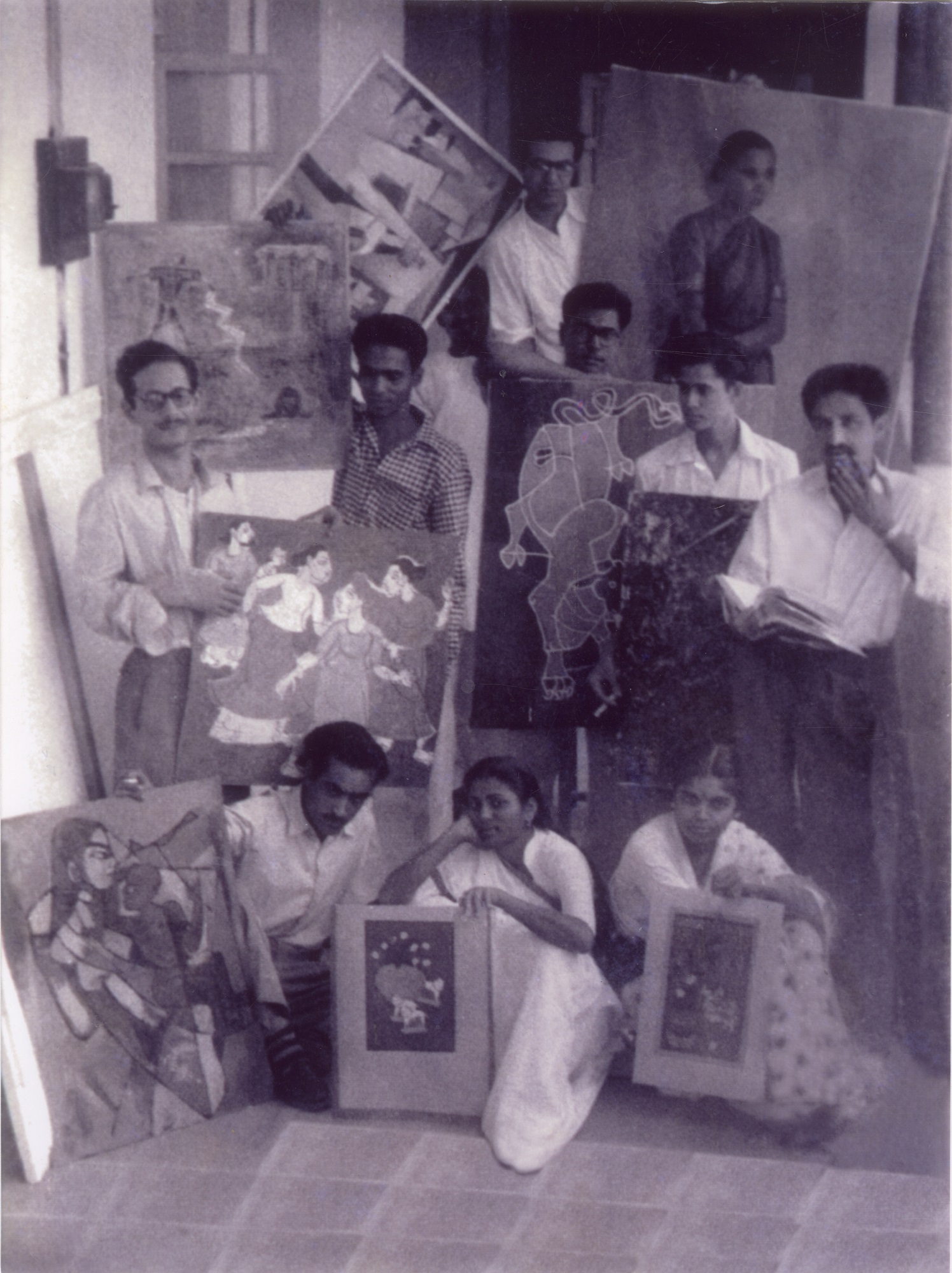

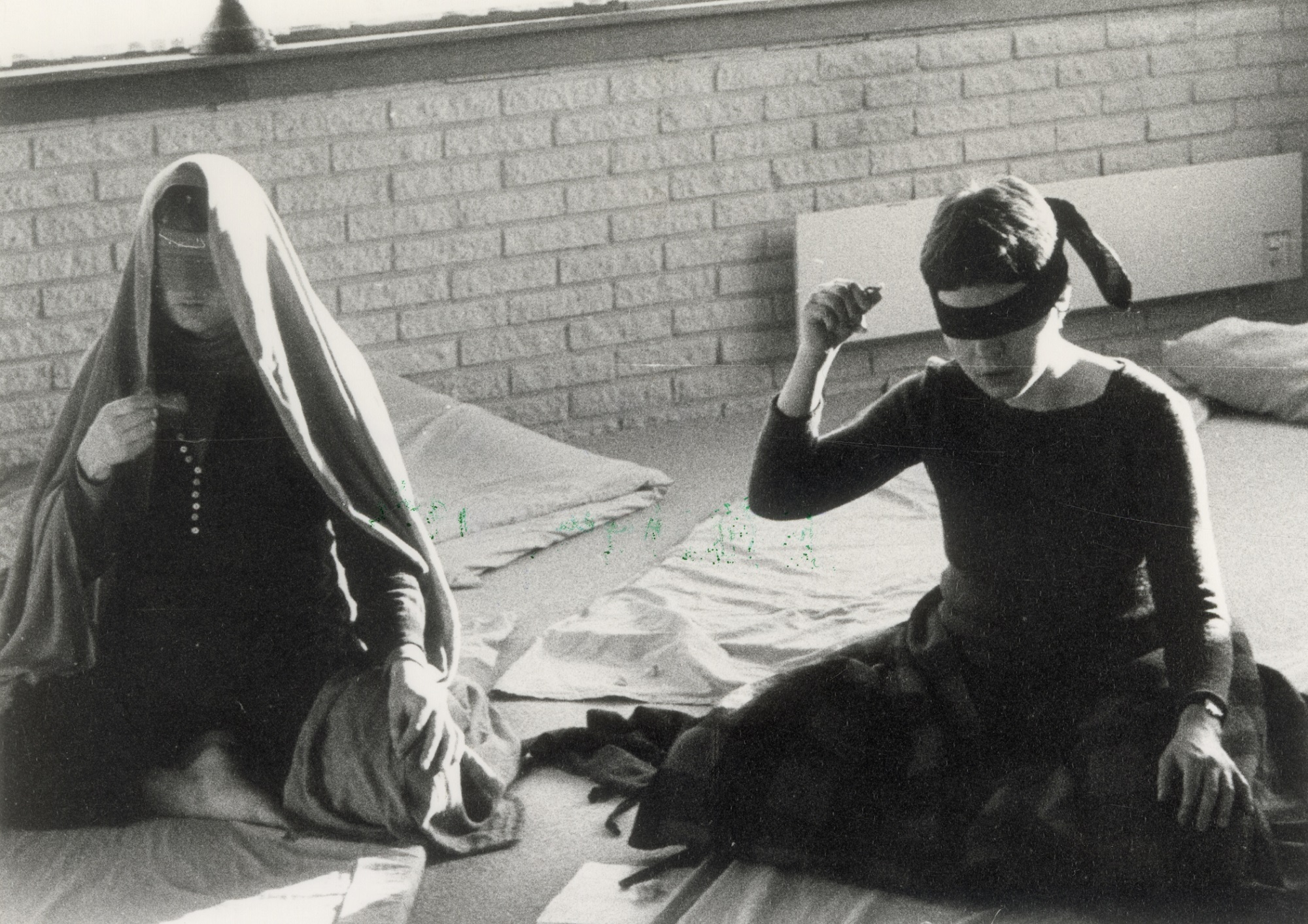

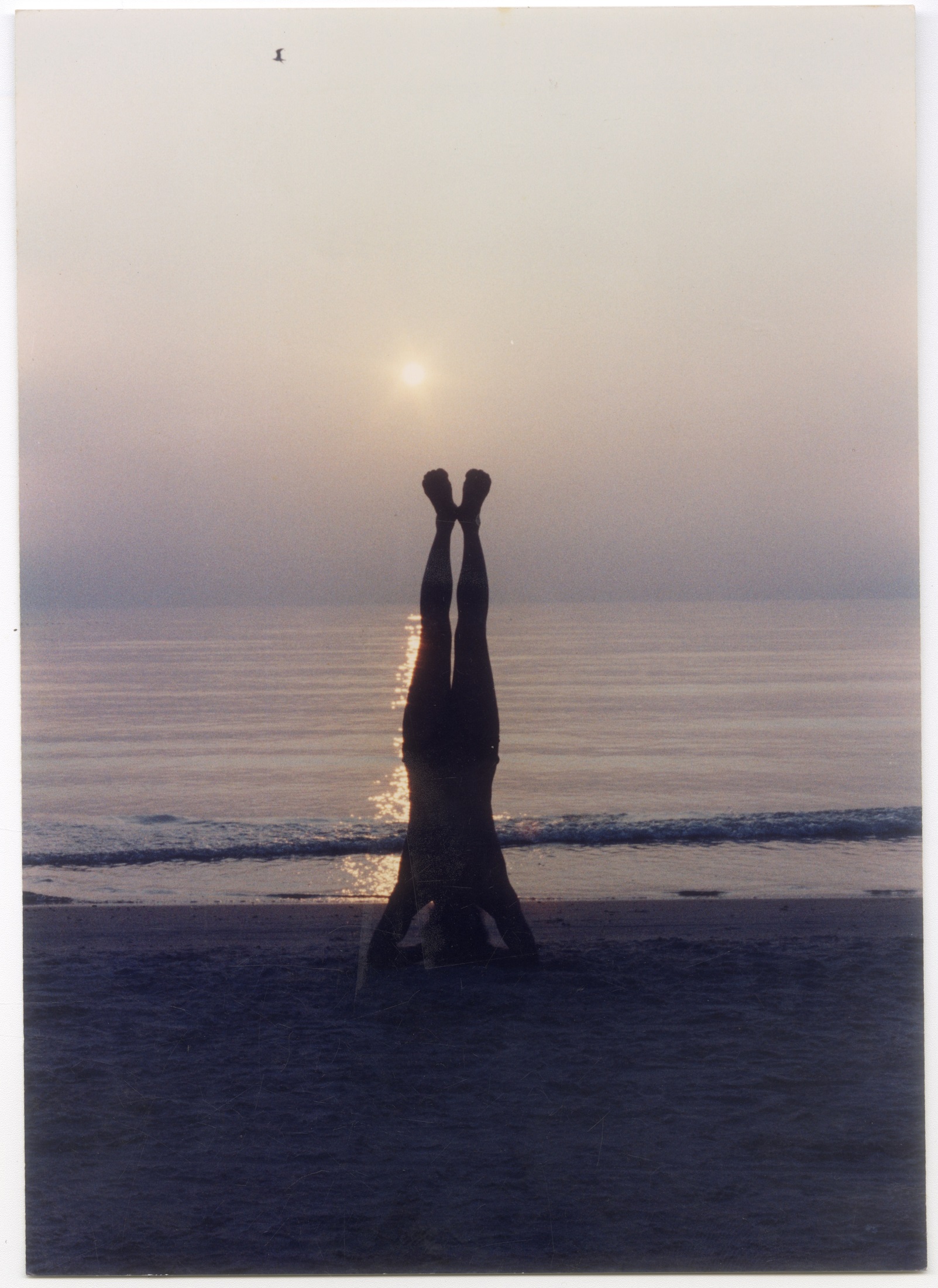

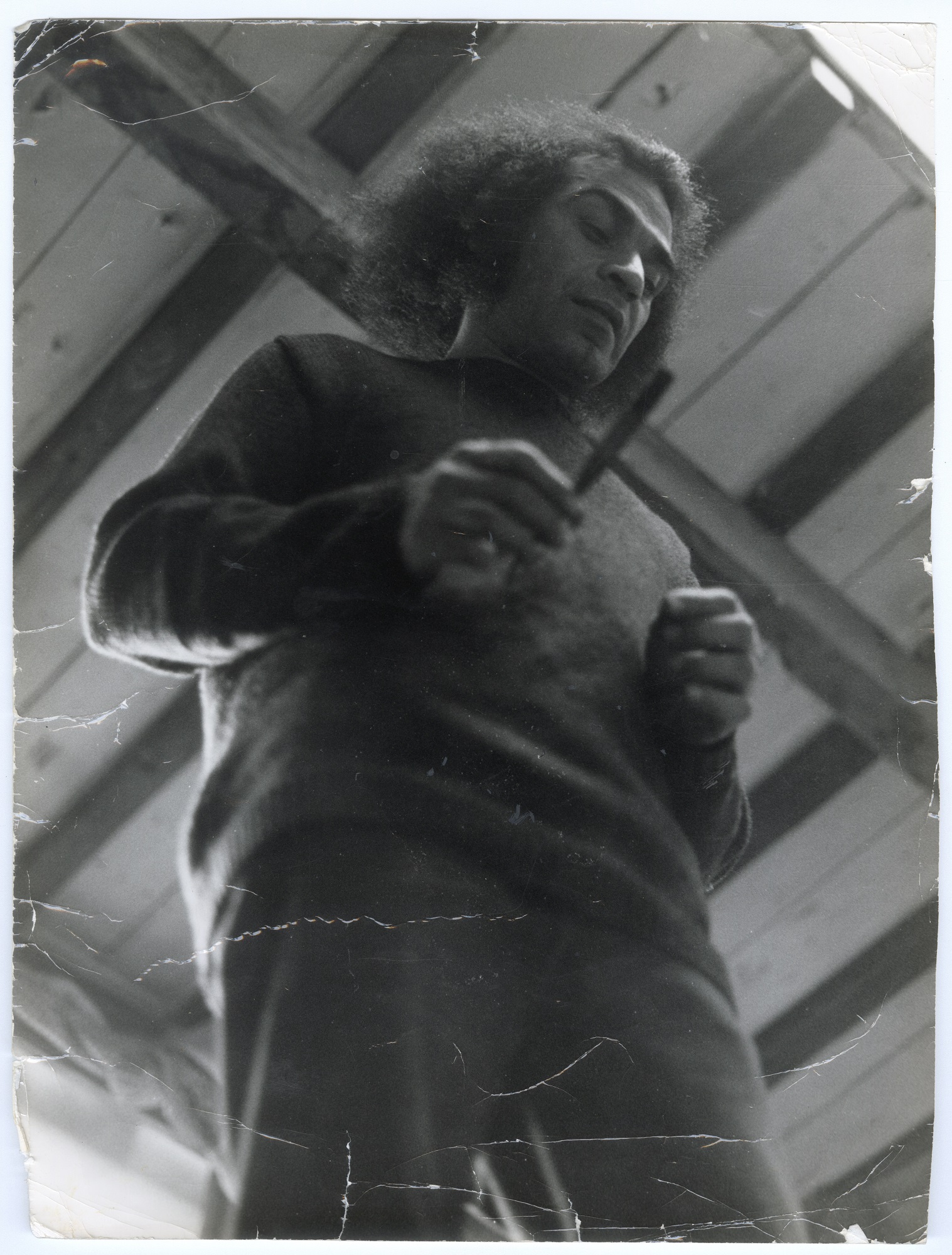

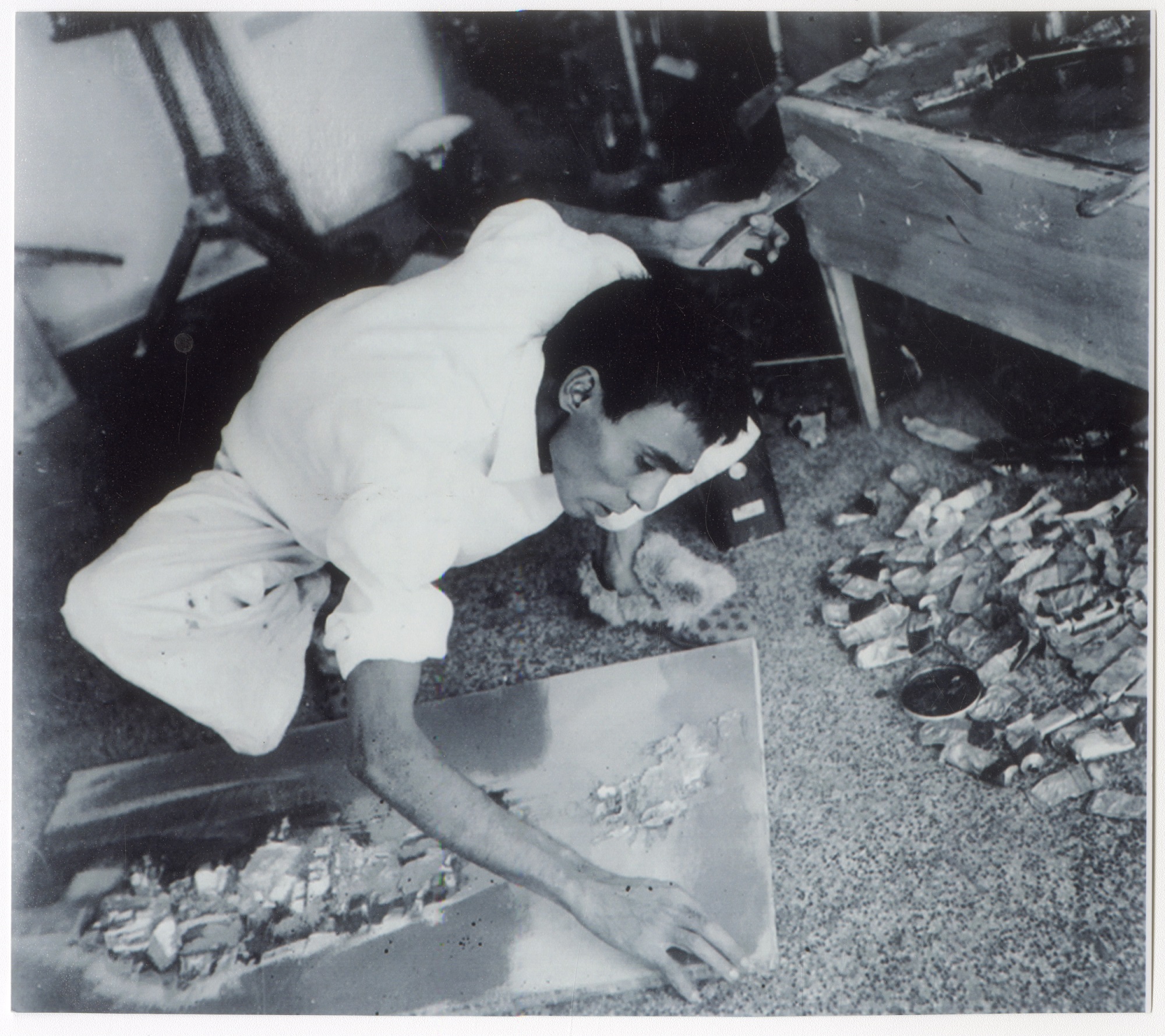

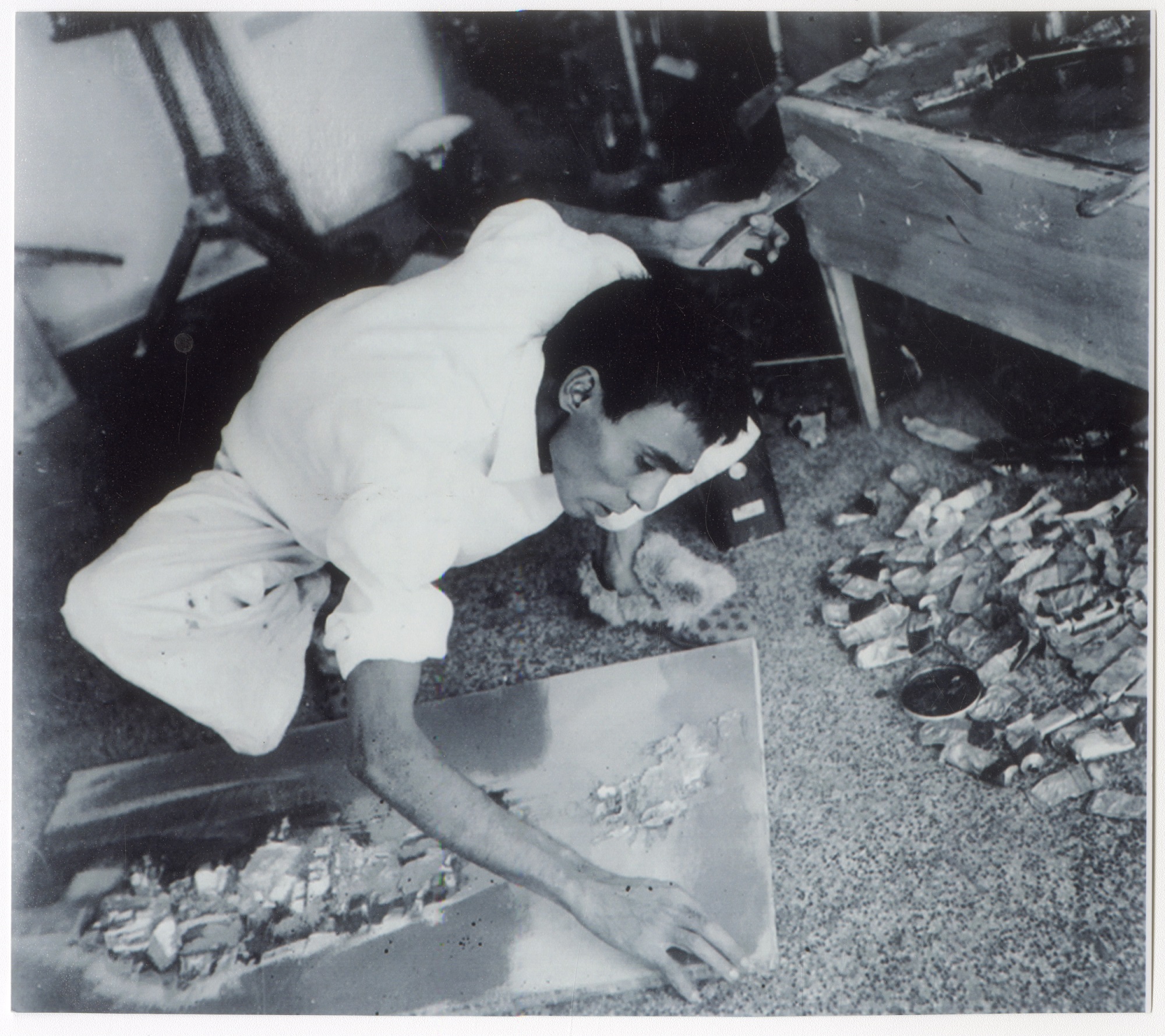

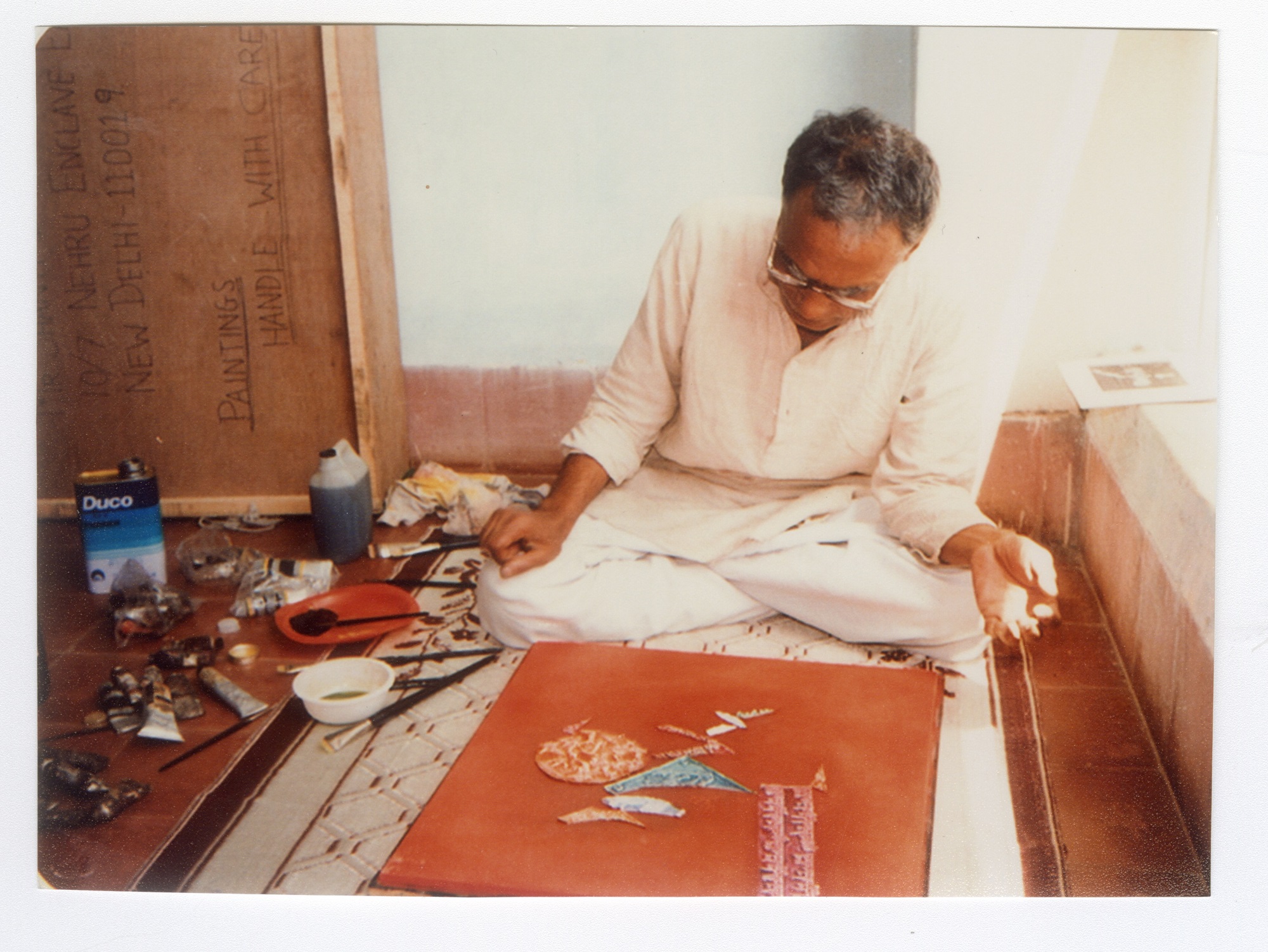

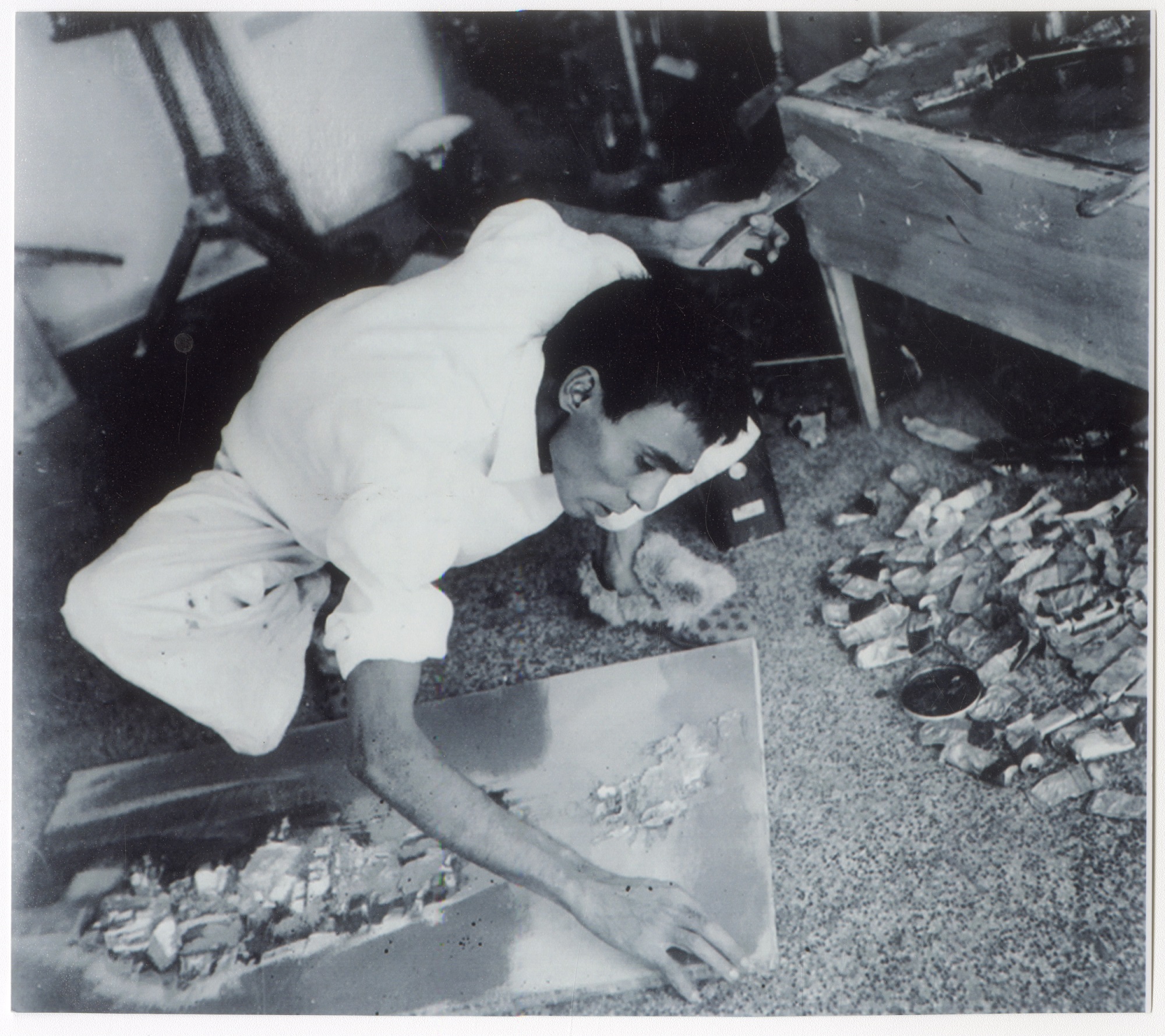

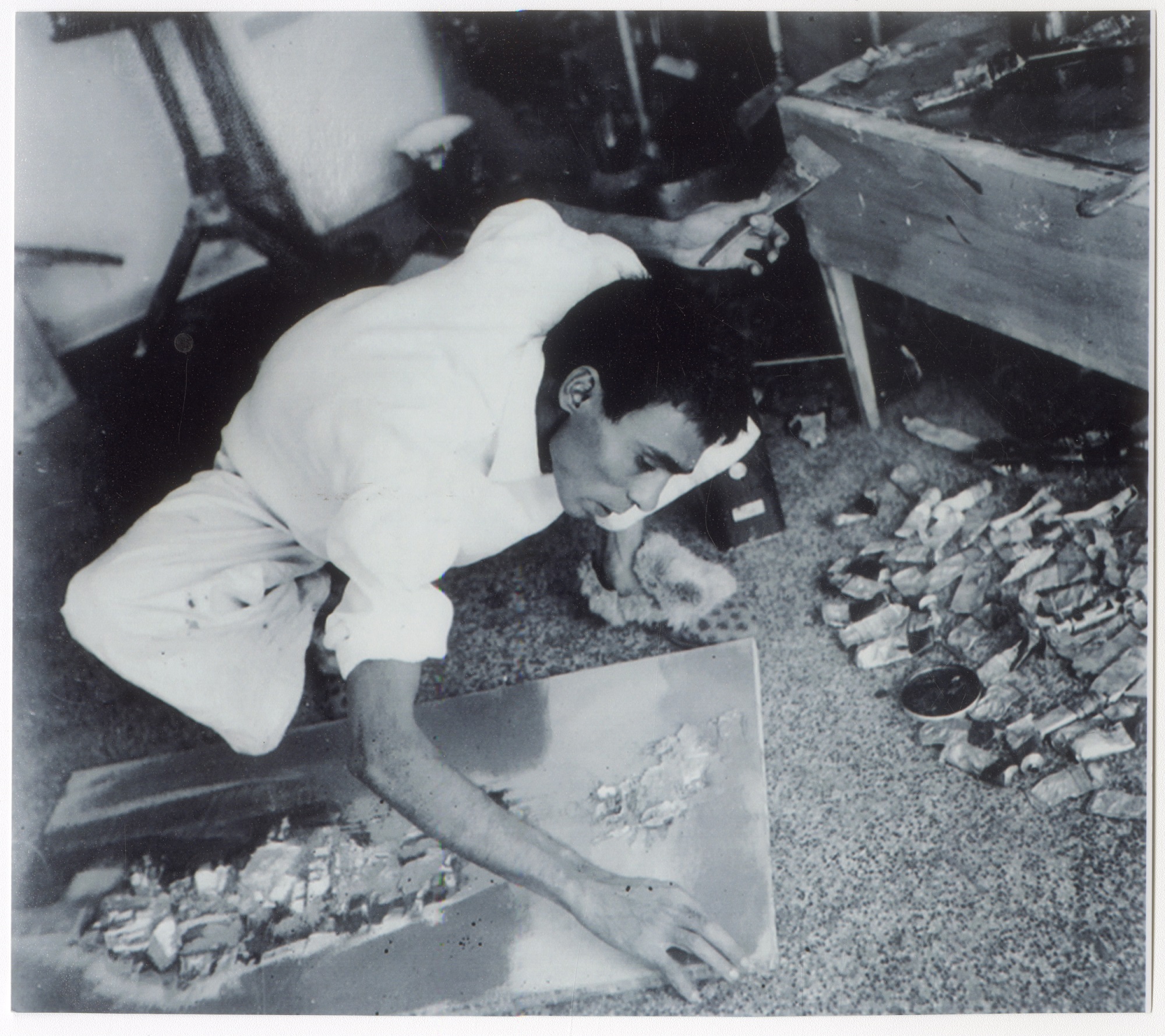

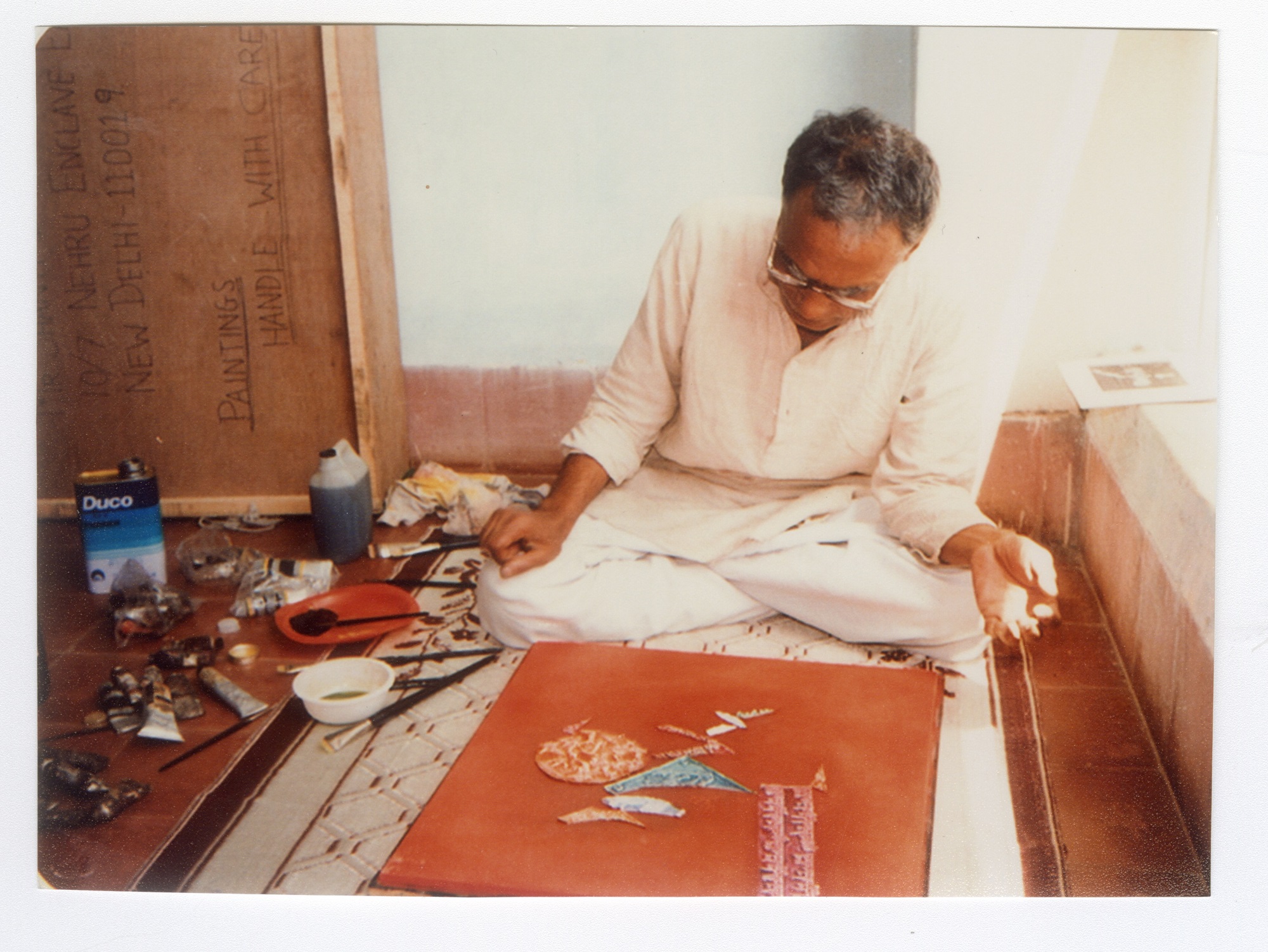

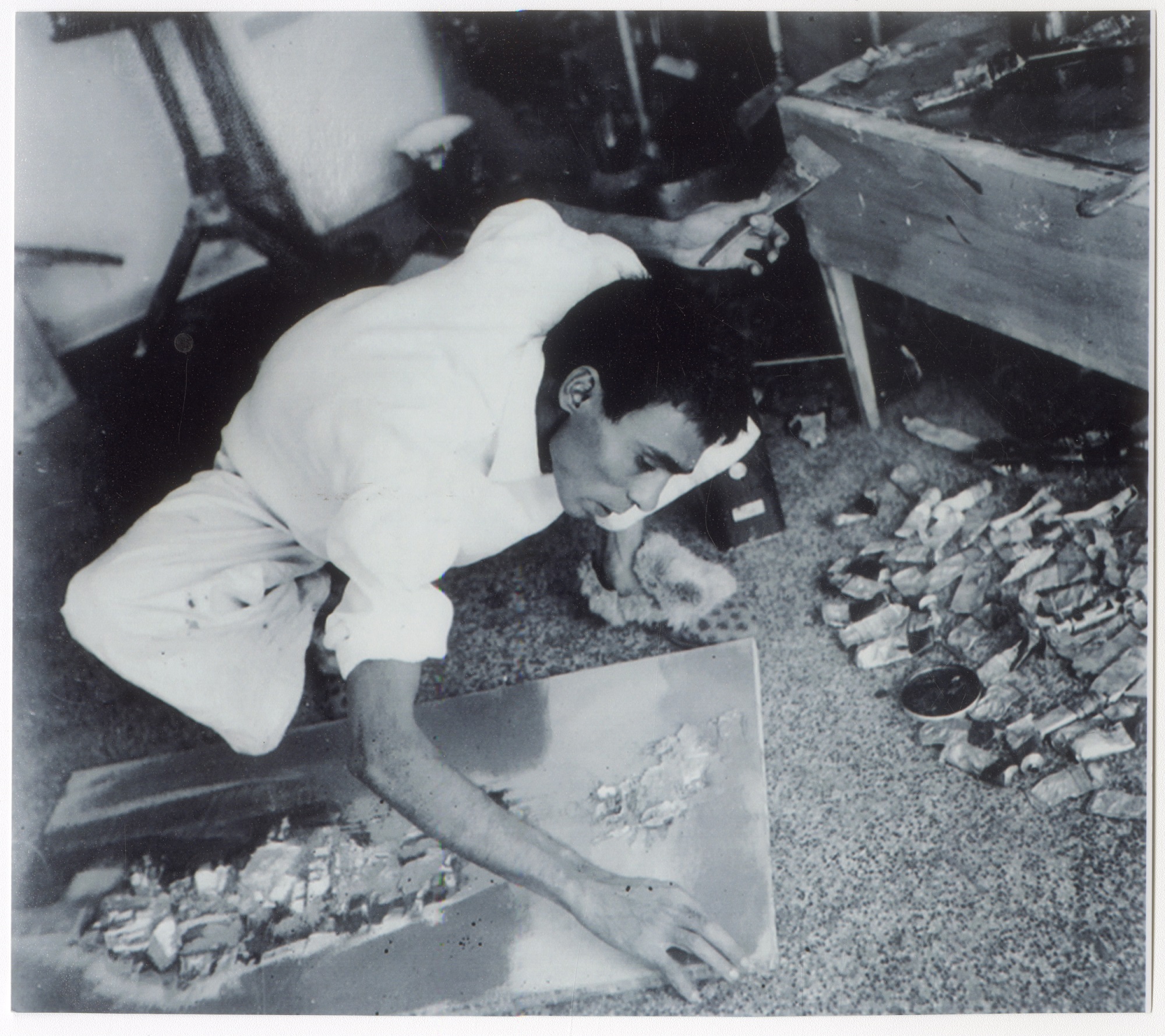

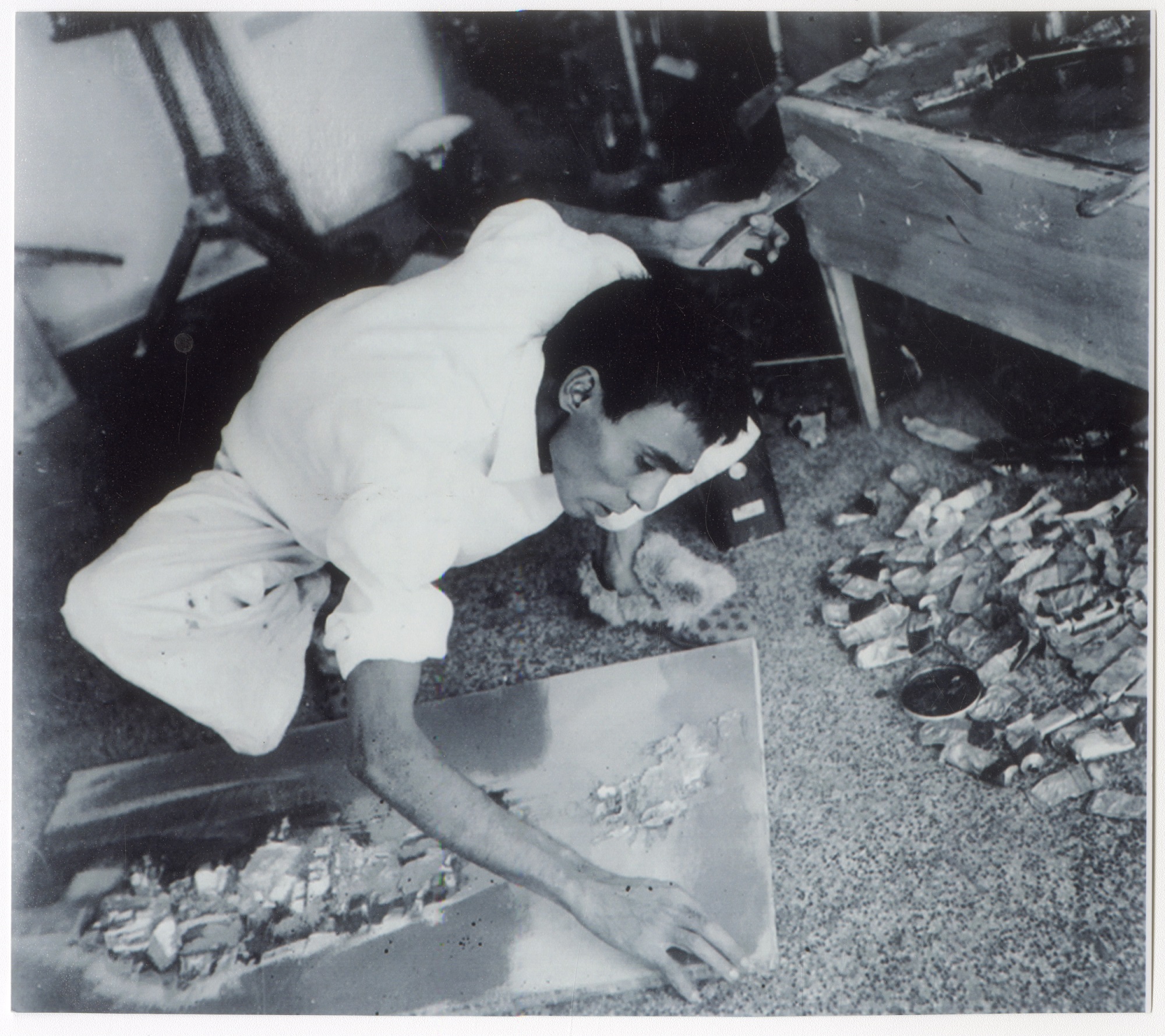

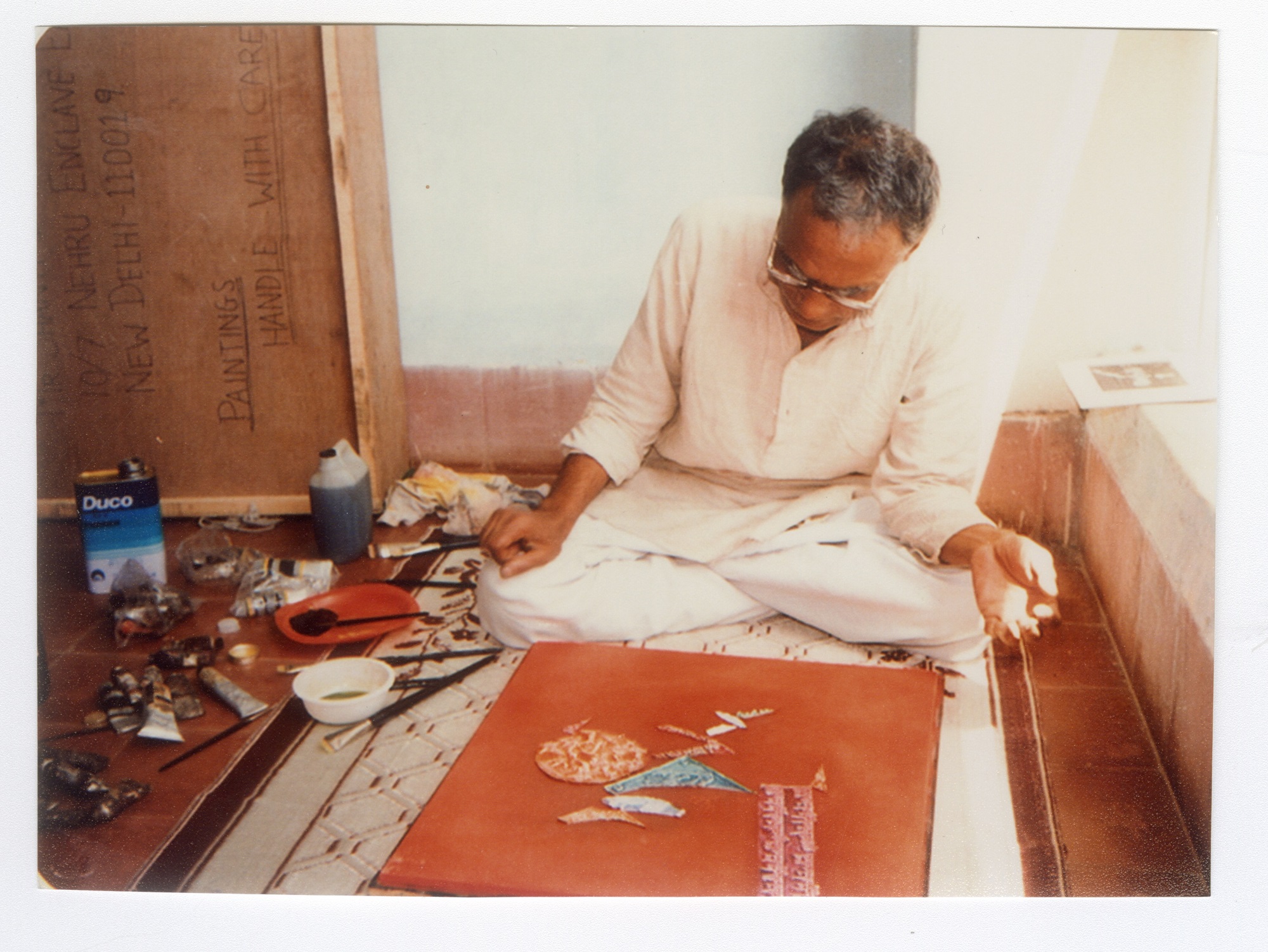

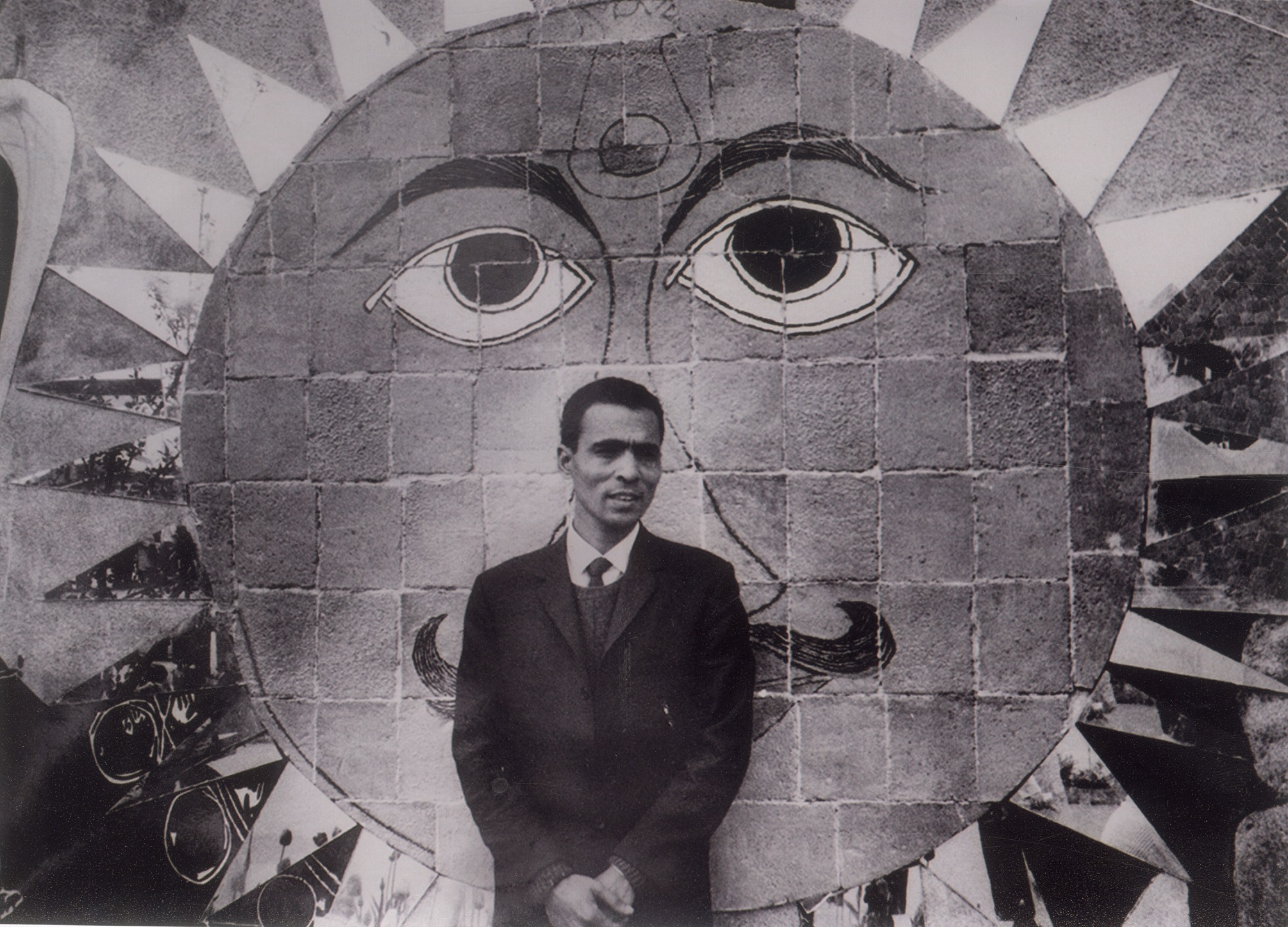

Portrait of young Shanti Dave

c. 1960s, Digital print, 5 x 7 in.

Collection: DAG

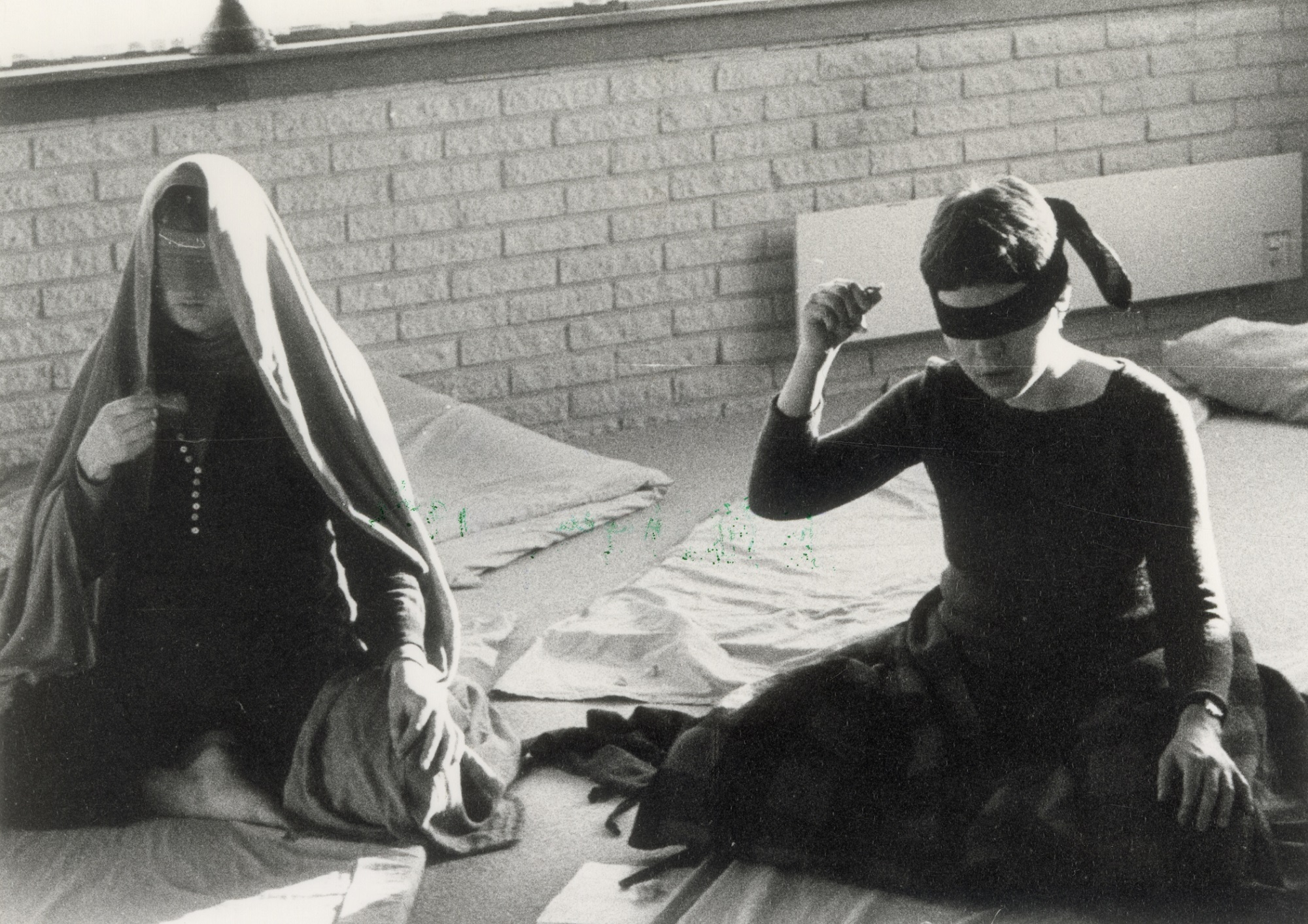

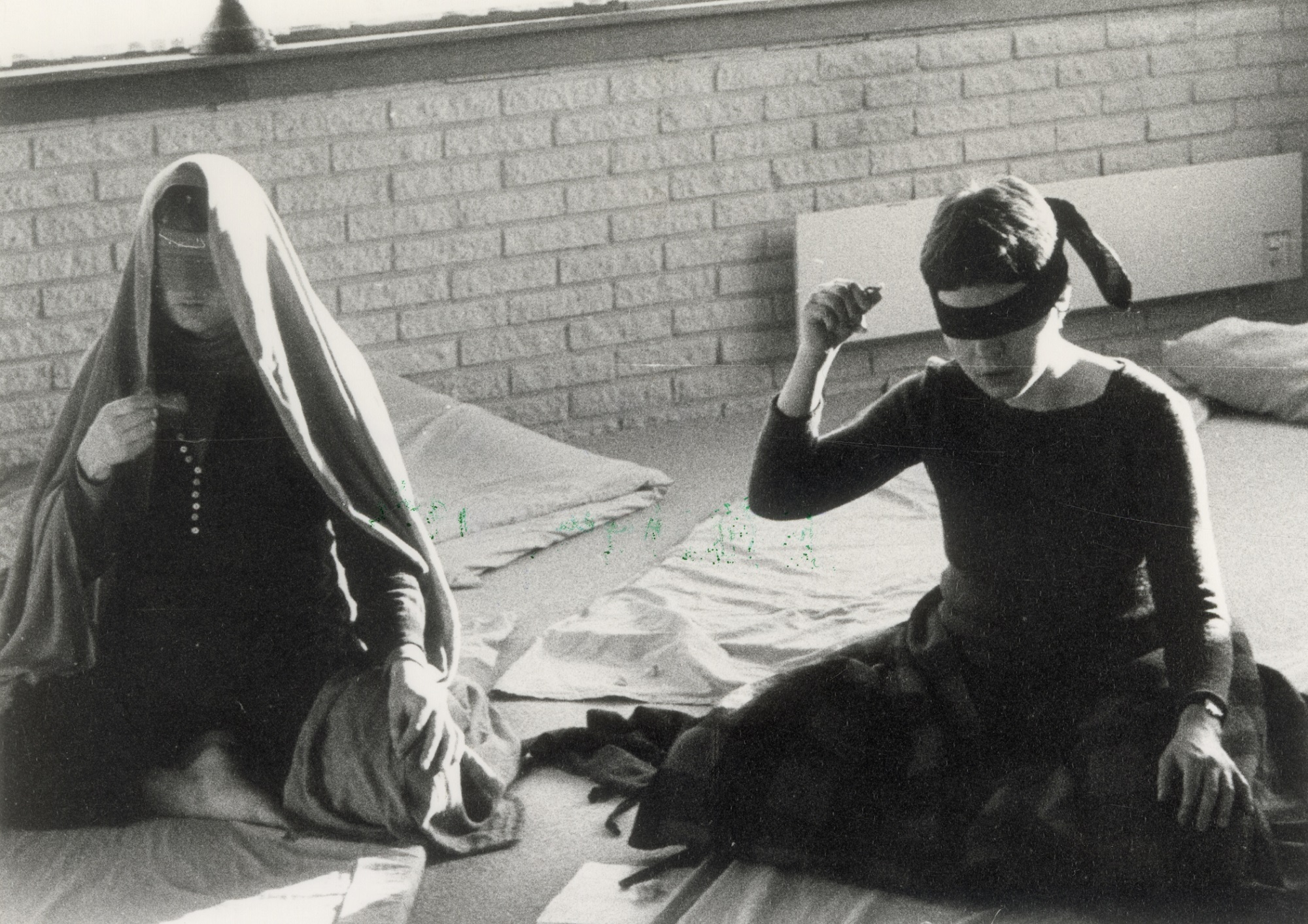

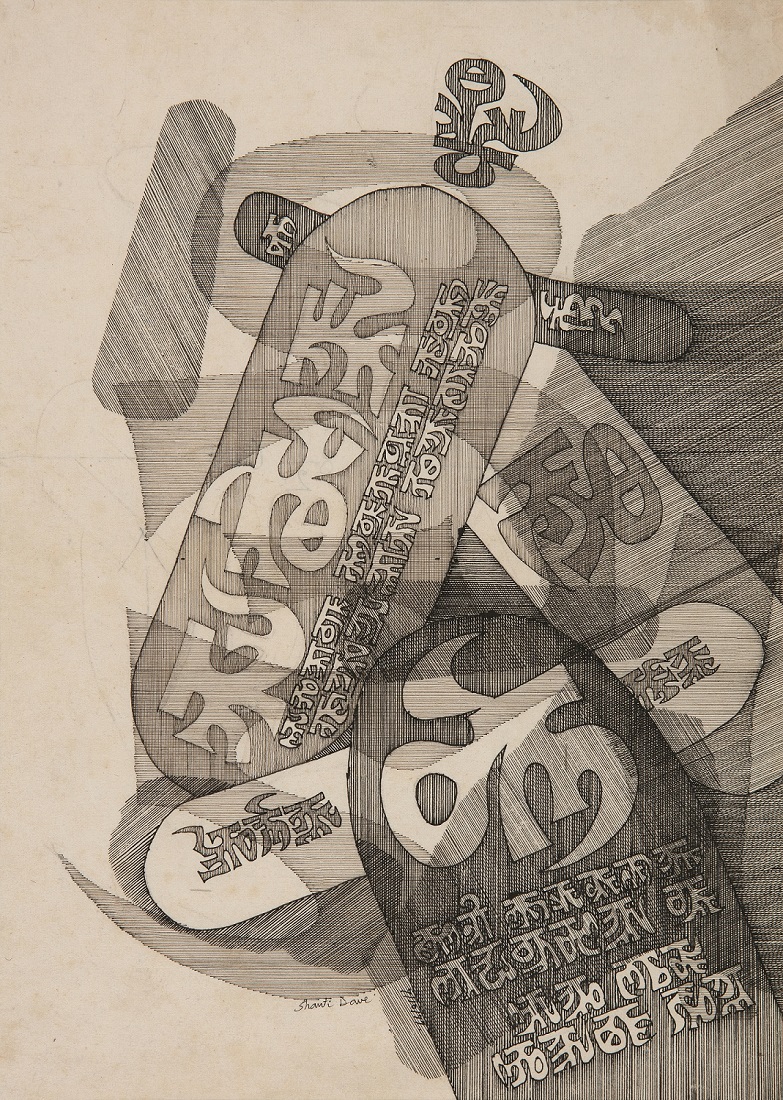

Shanti Dave (b. 1931)Born in Gujarat in 1931, Shanti Dave began his career as a signboard painter before he went to M. S. University in Baroda, Faculty of Fine Arts to receive his formal education. It is during his years as a signboard painter that he developed an interest in the letters in their bare form, denuded of any meaning whatsoever—letters which are not yet formed into words. This interest in the aesthetic of alphabets of any language, their specific shape and form, stayed with him throughout his long career; he never grew out of it. |

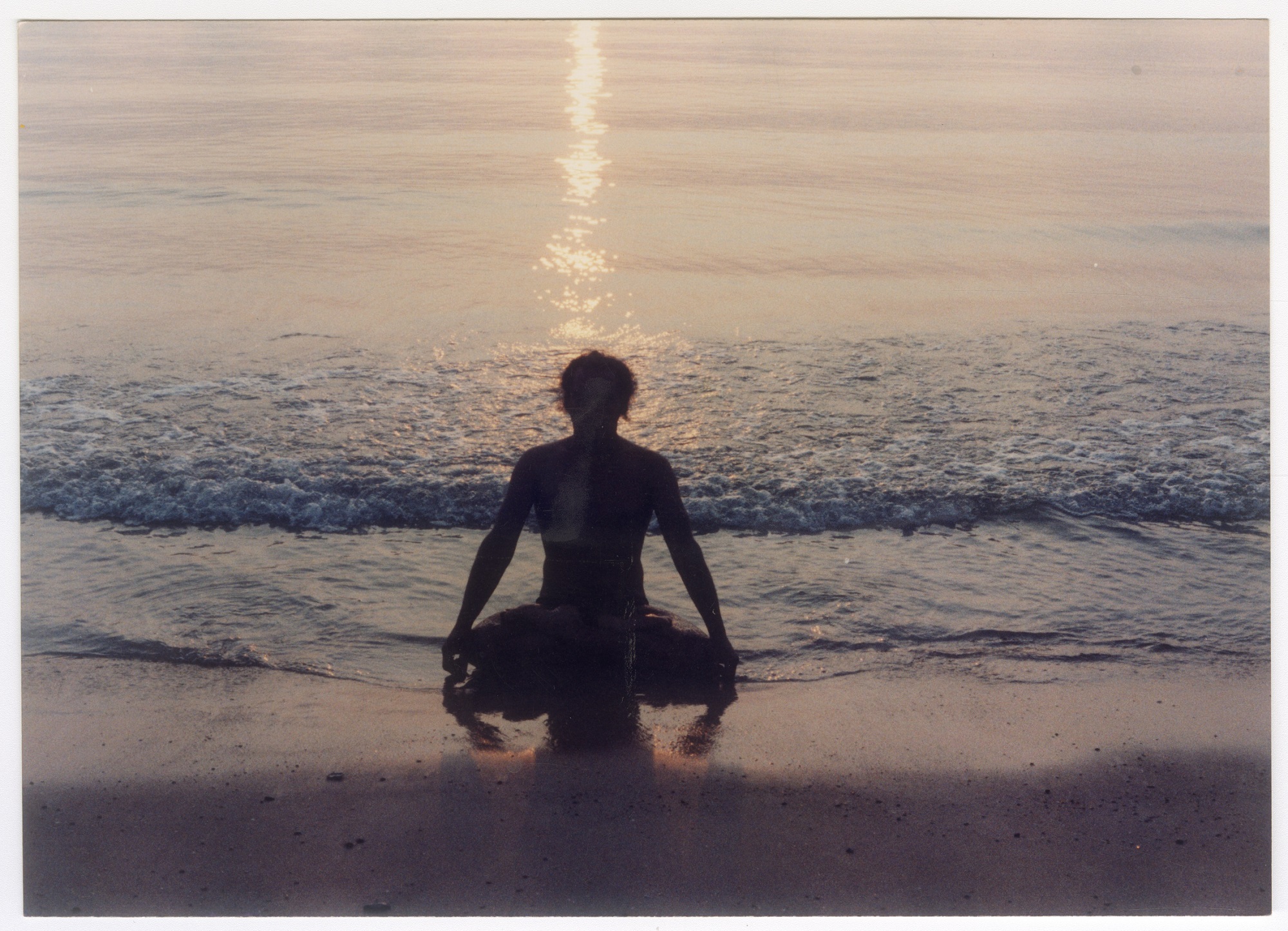

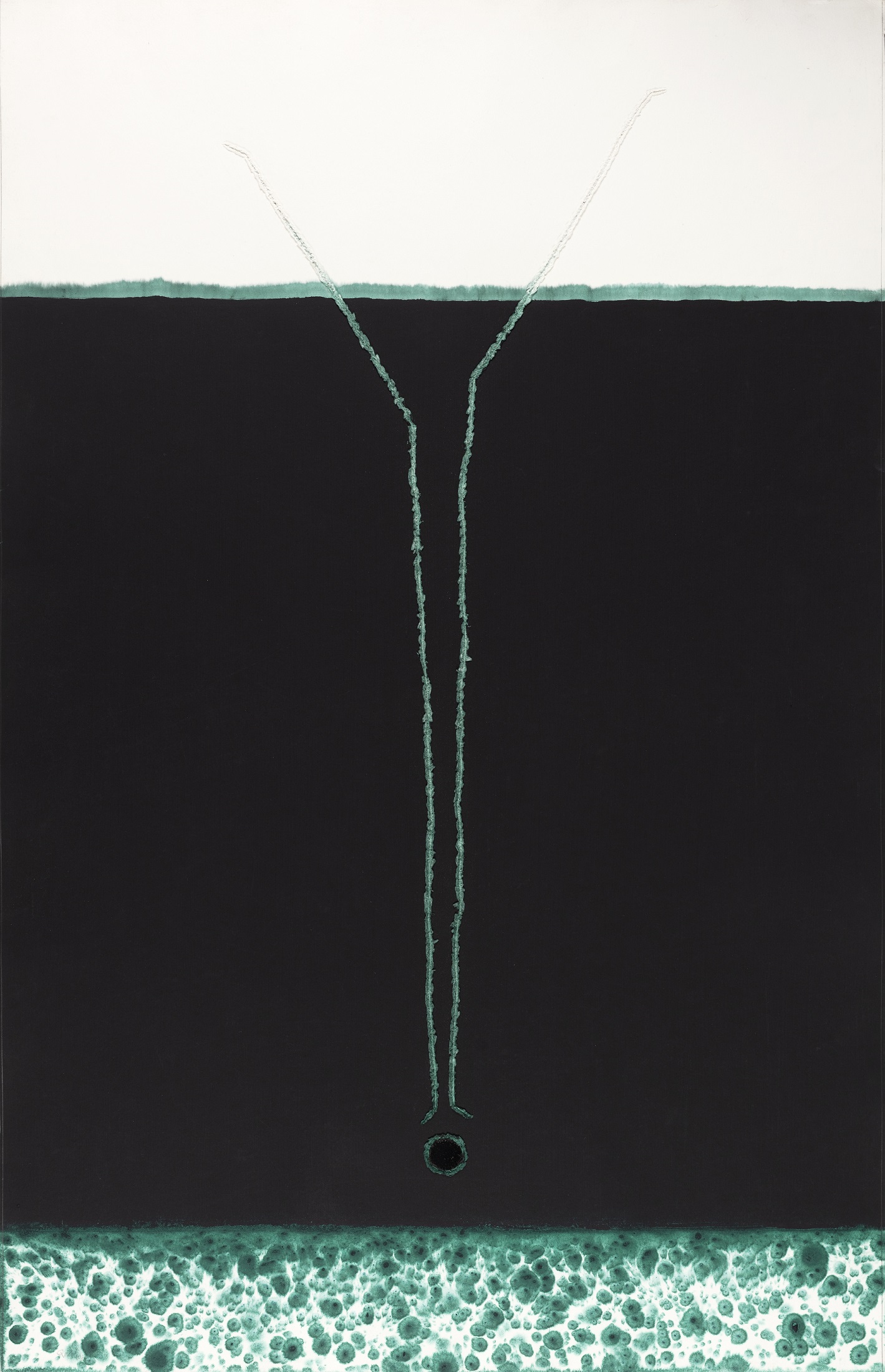

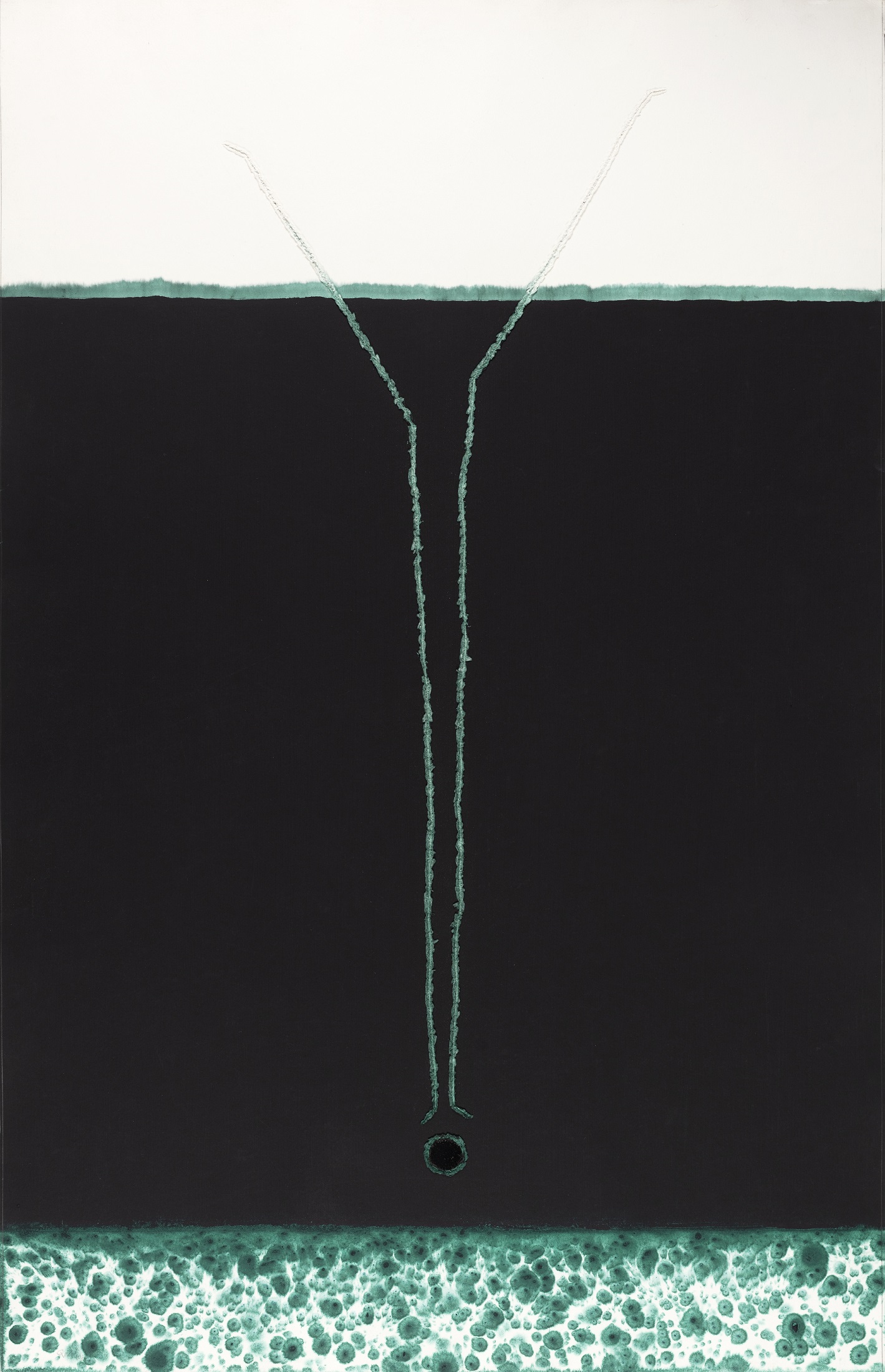

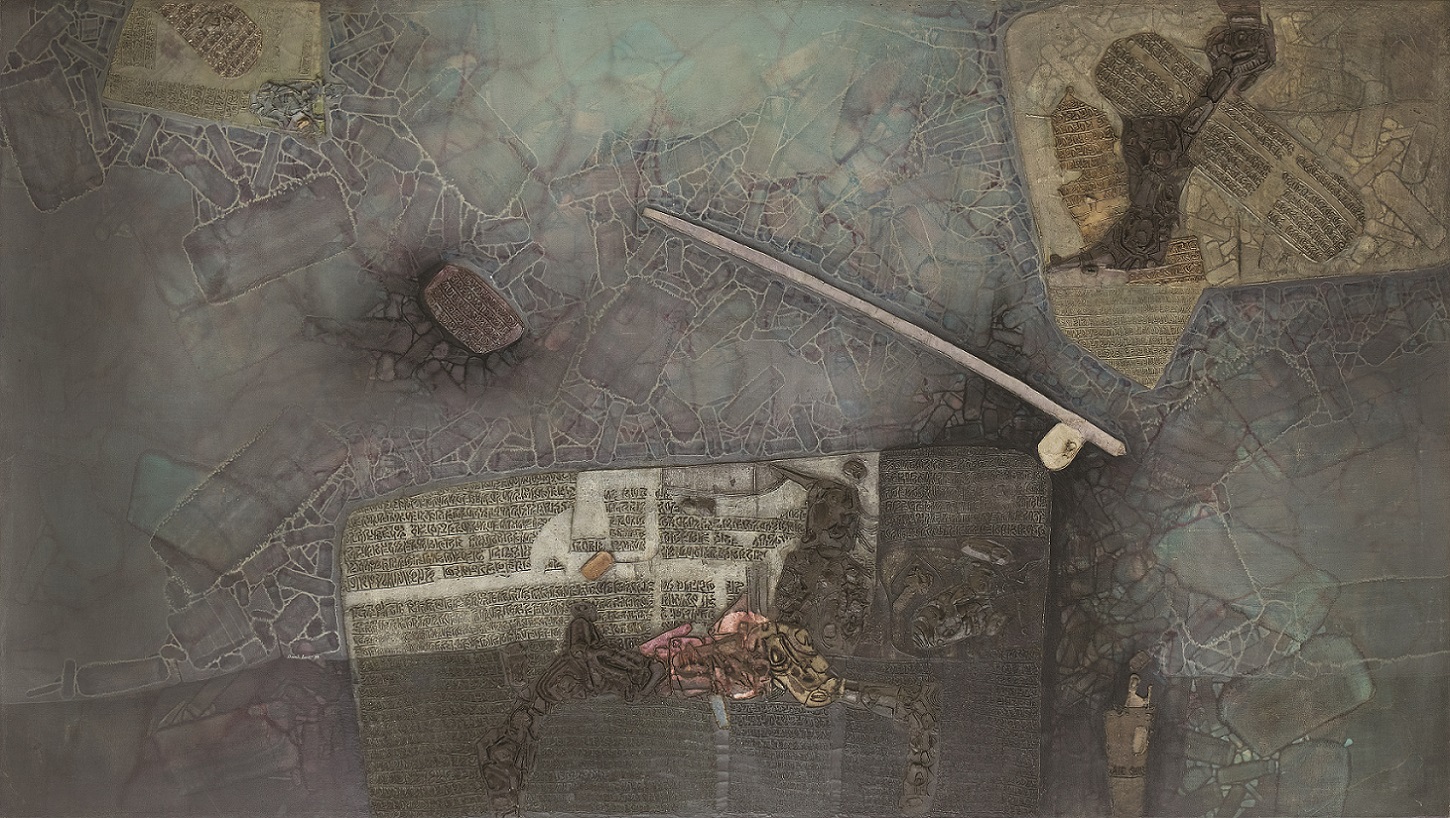

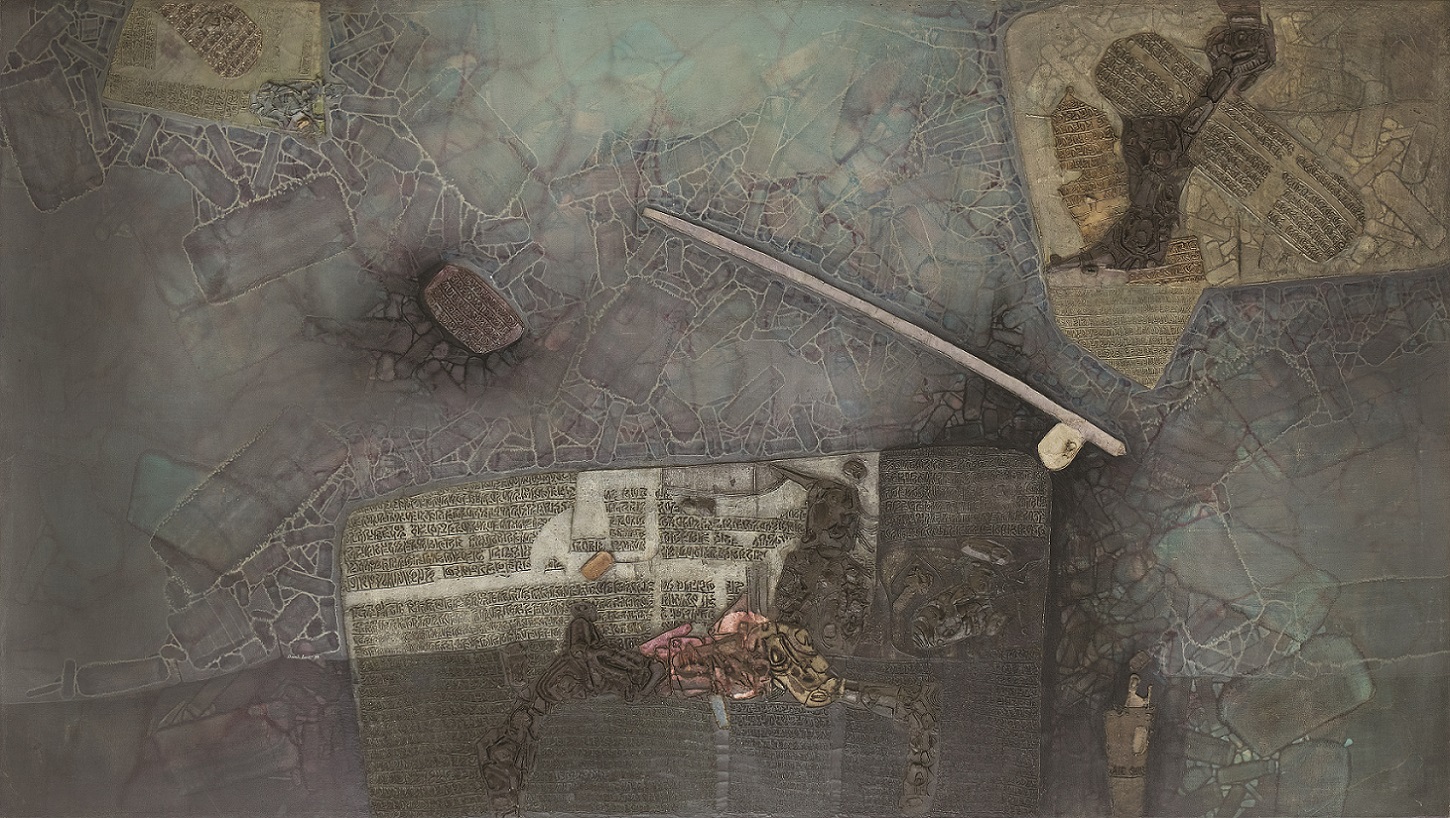

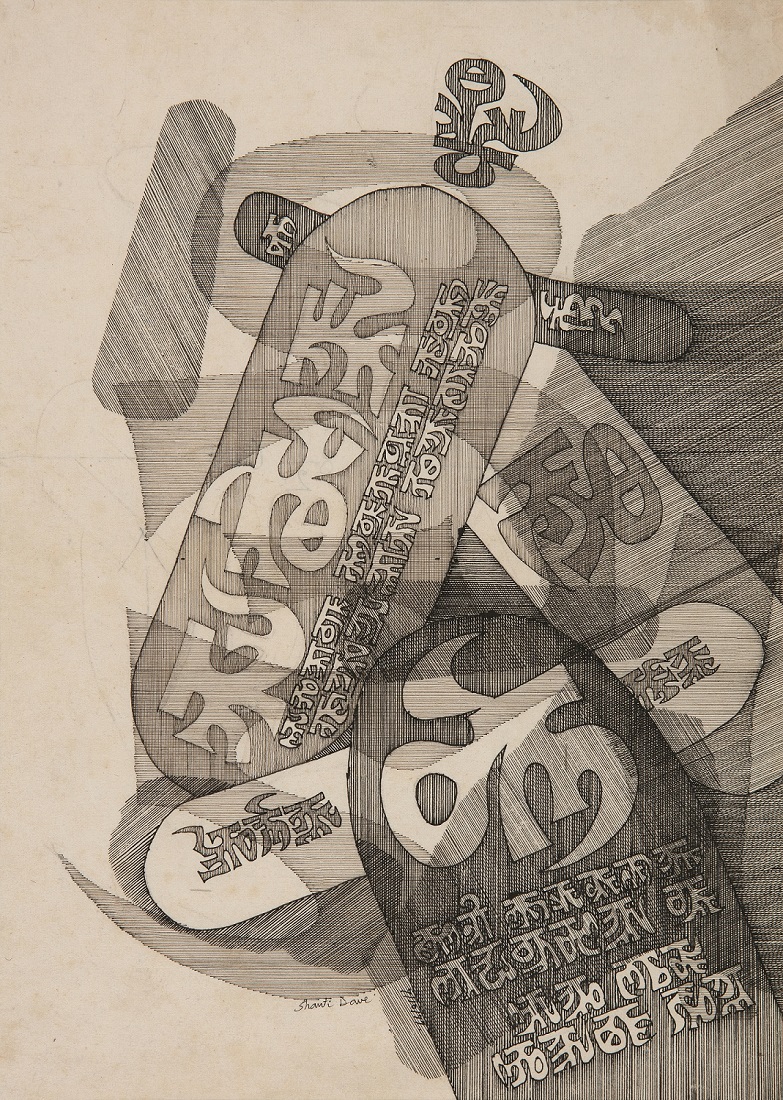

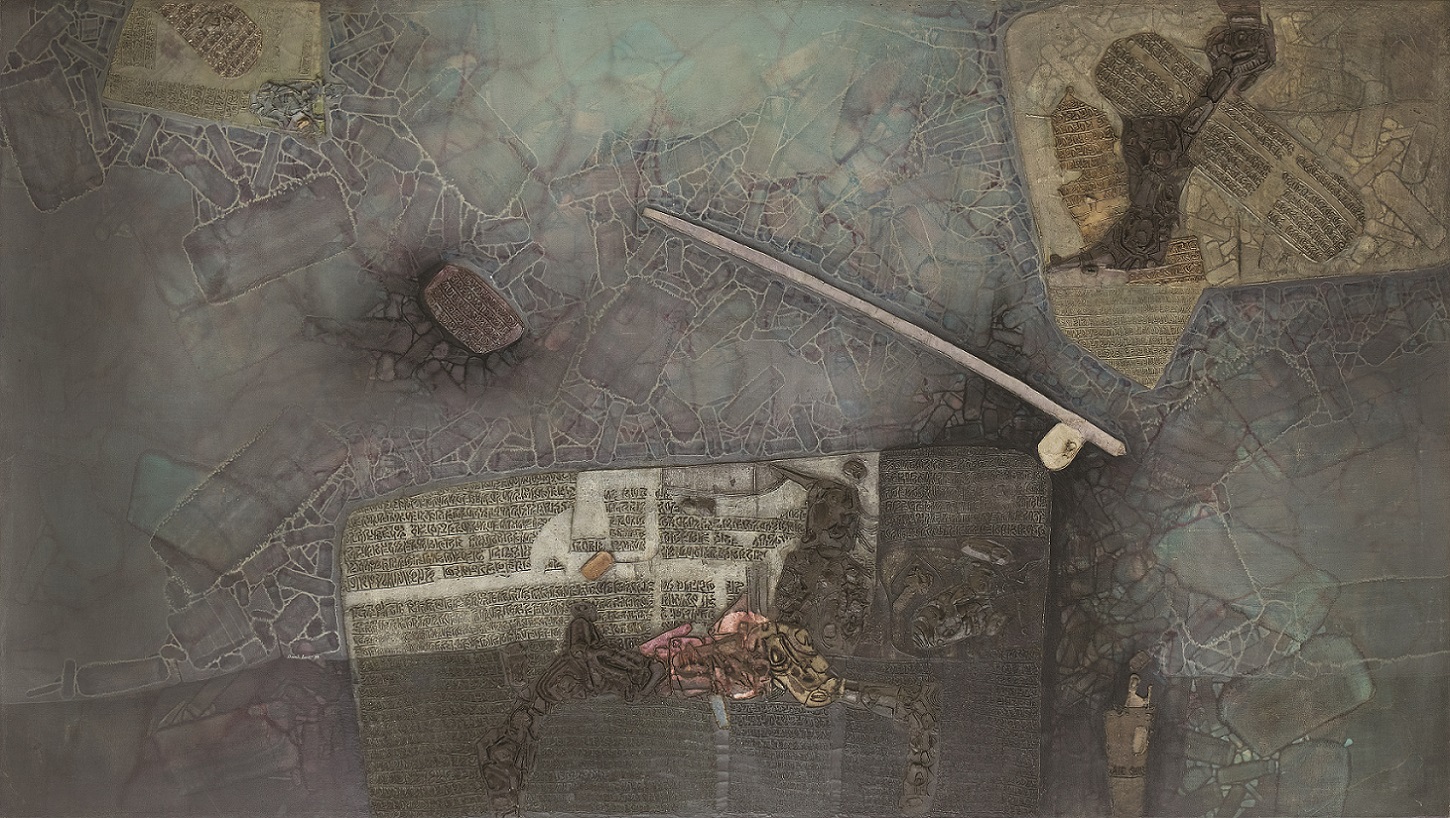

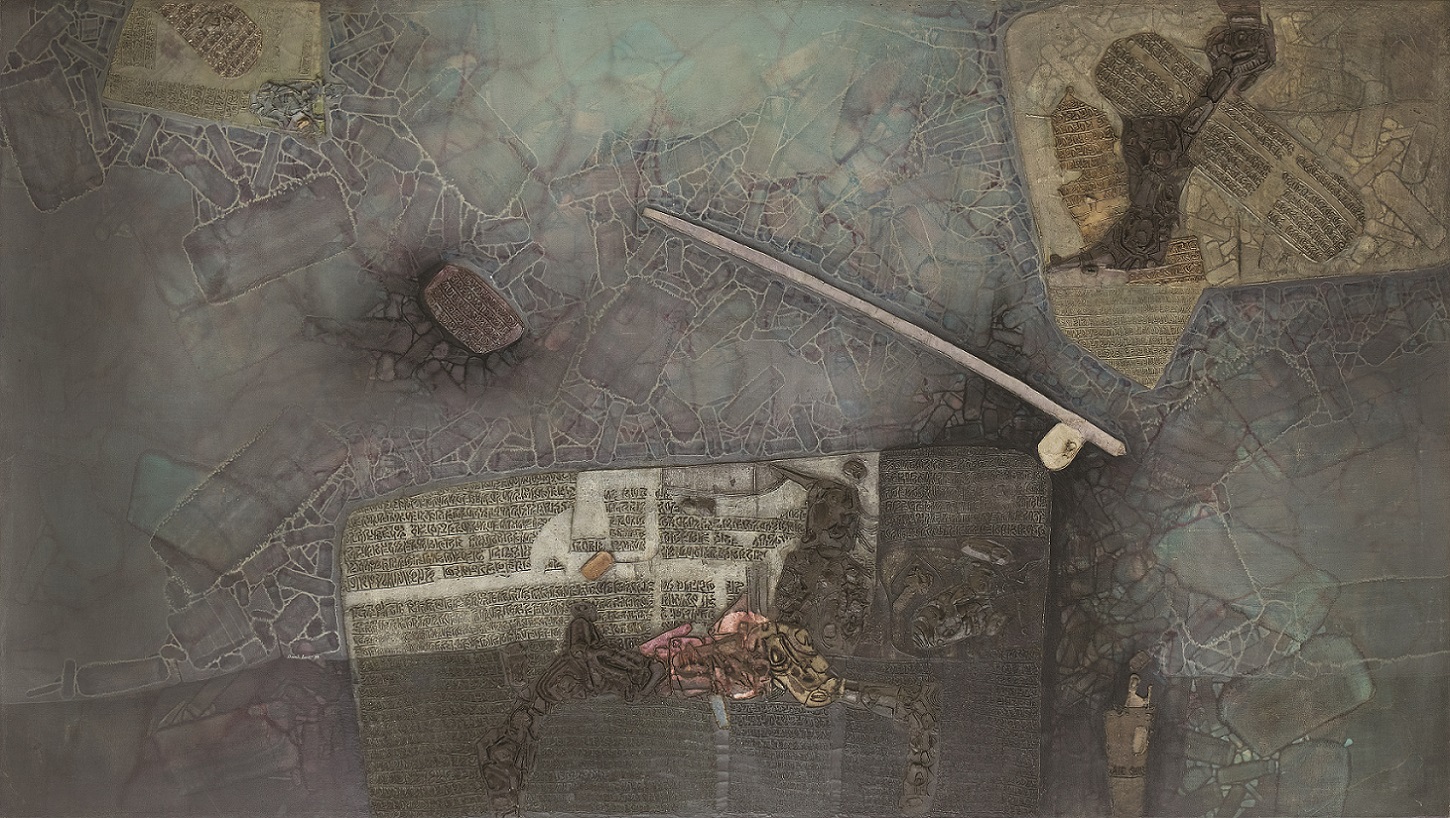

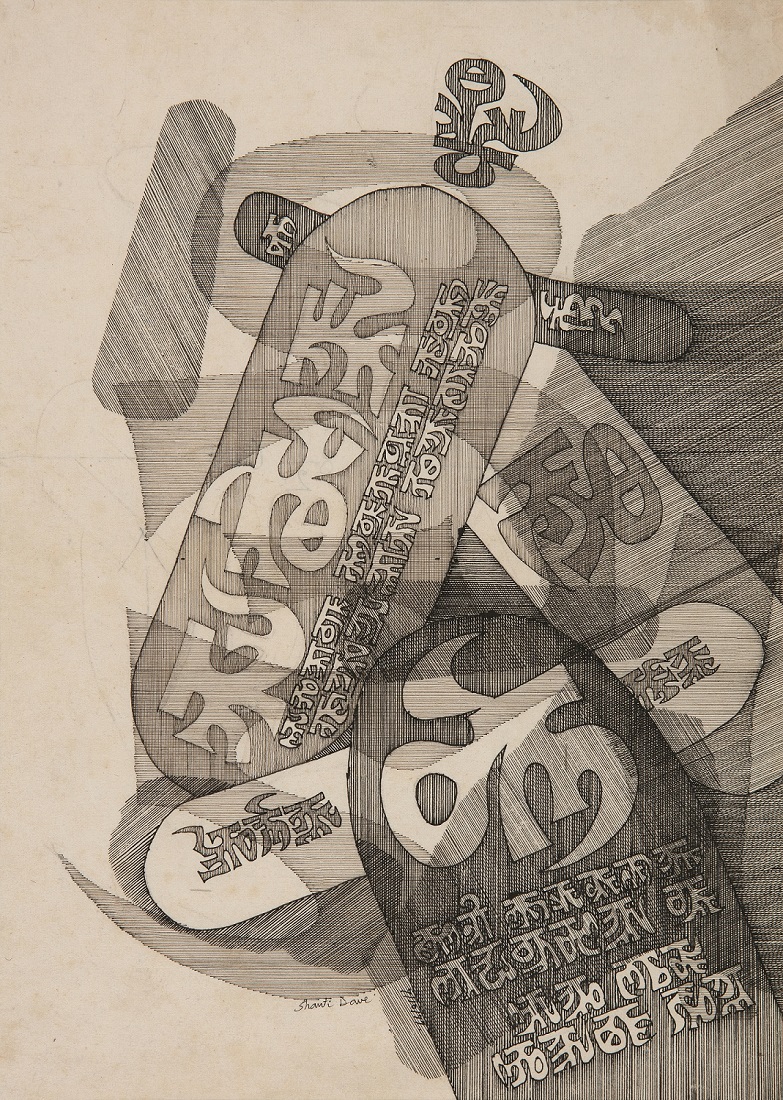

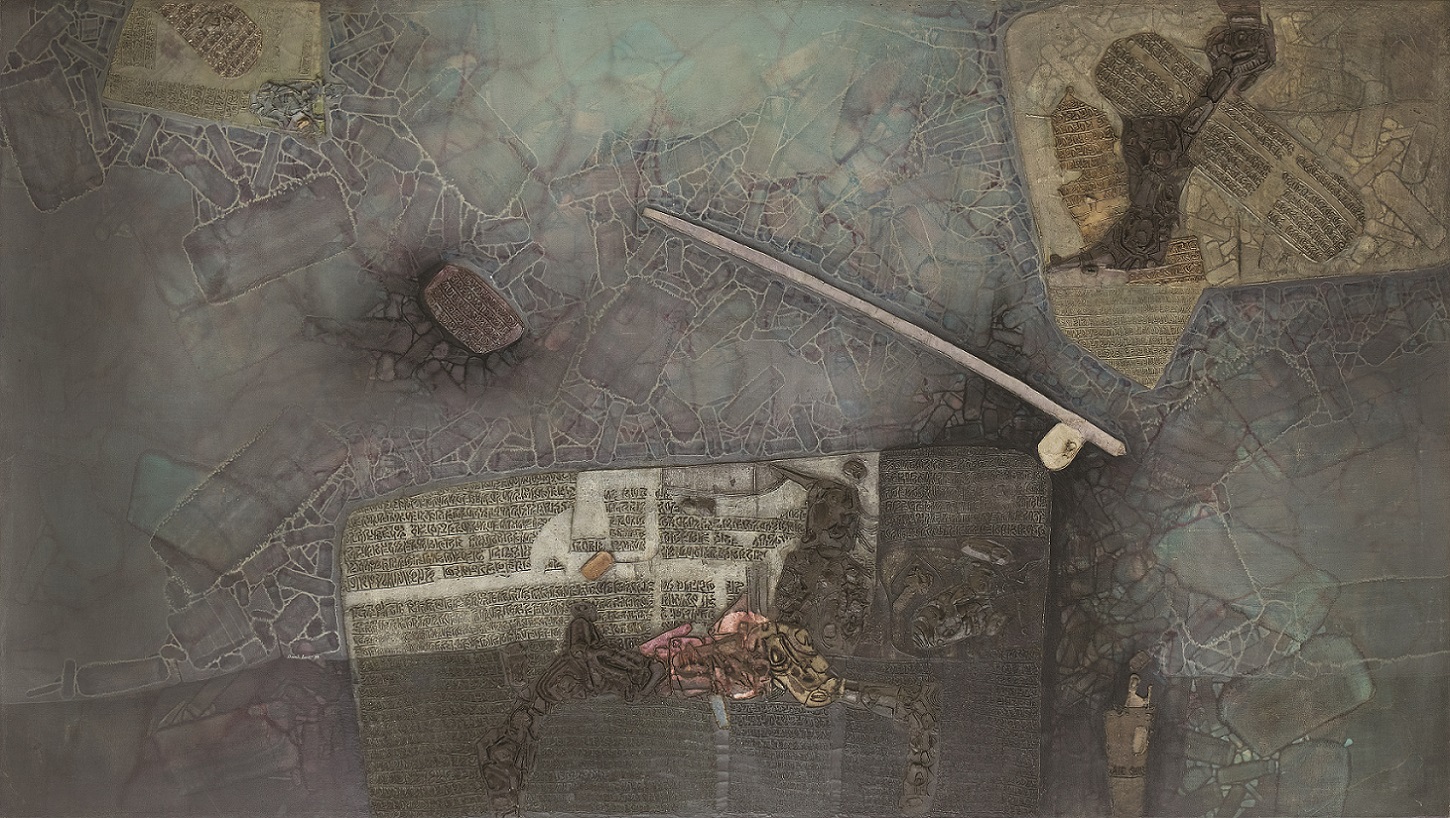

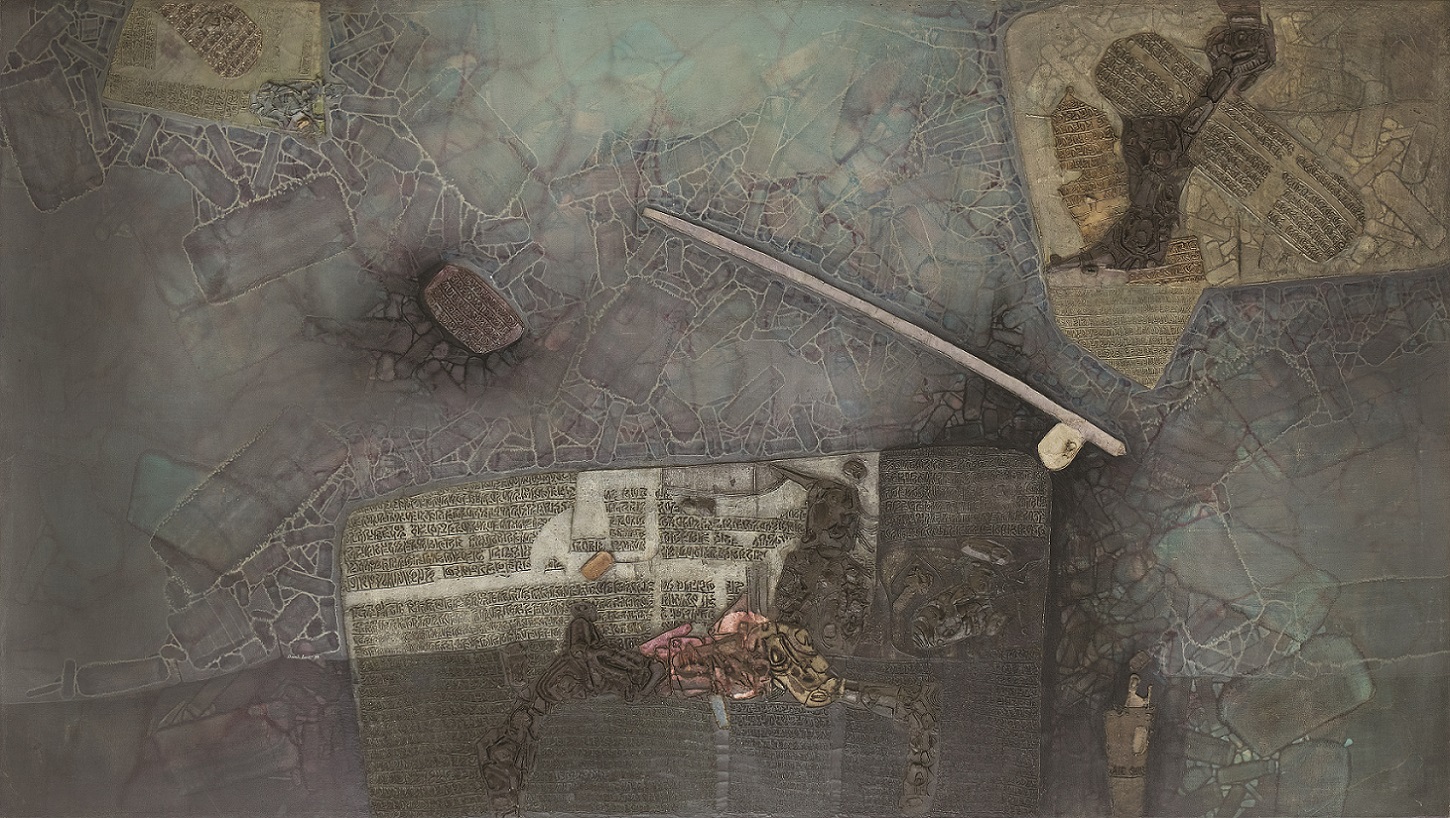

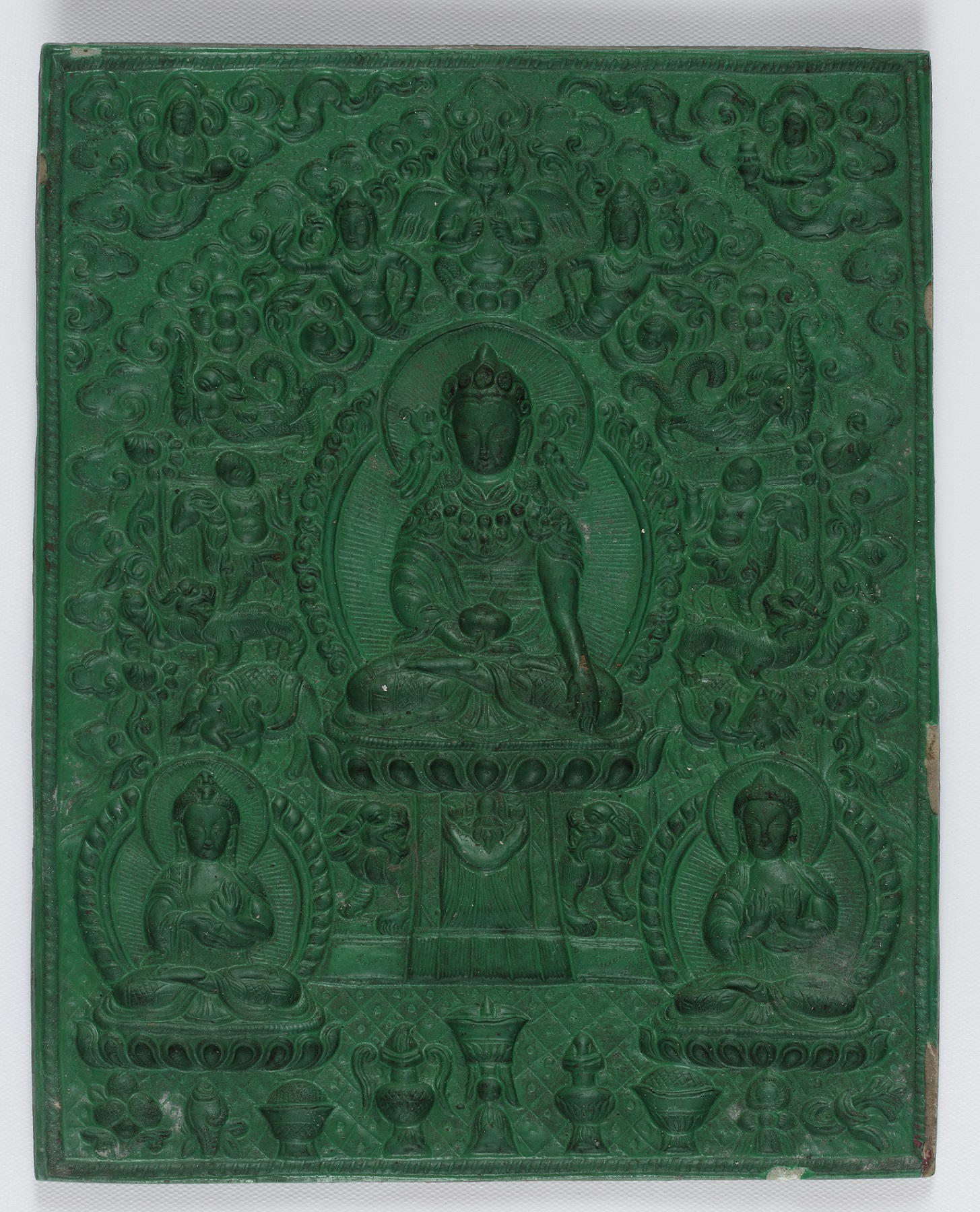

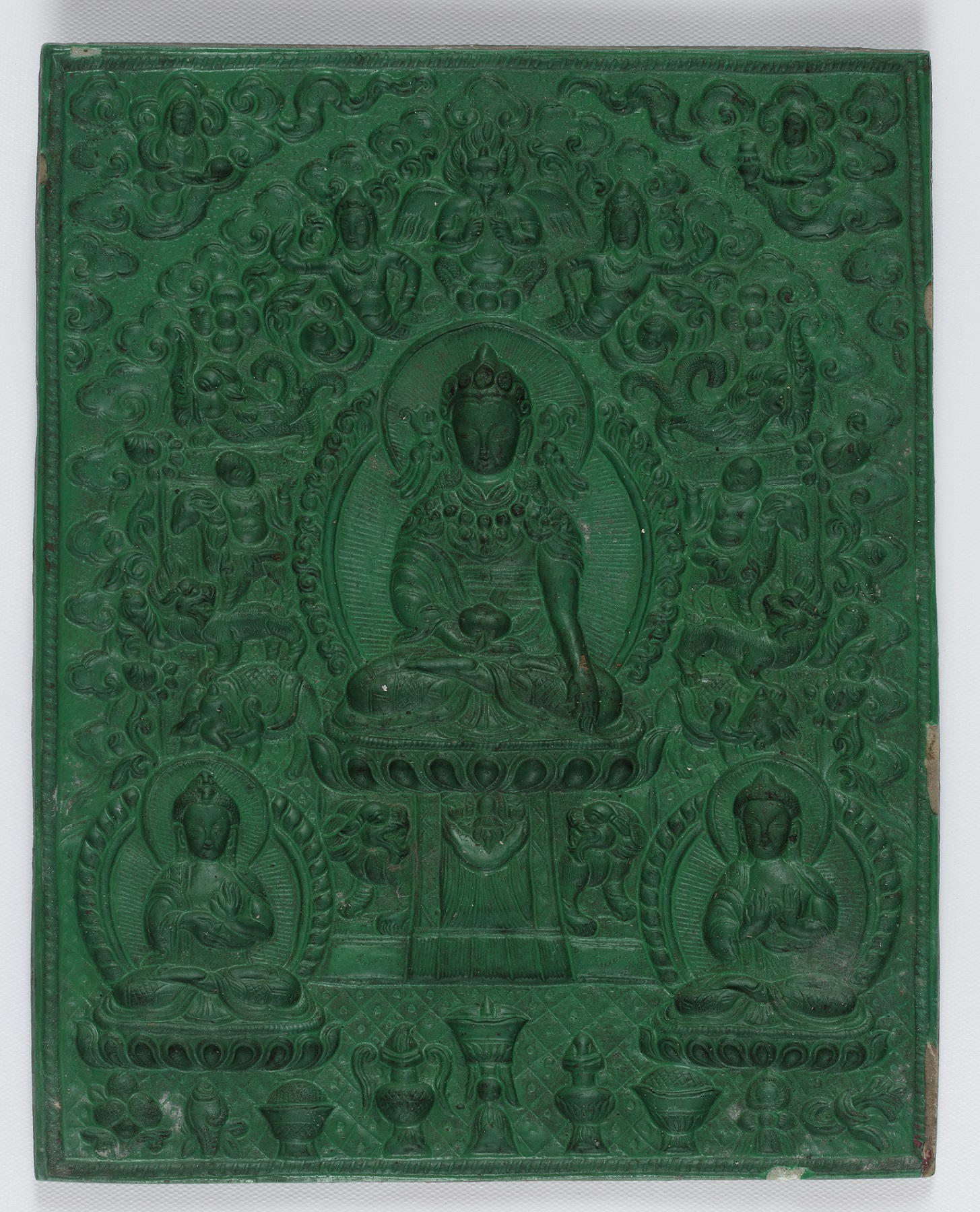

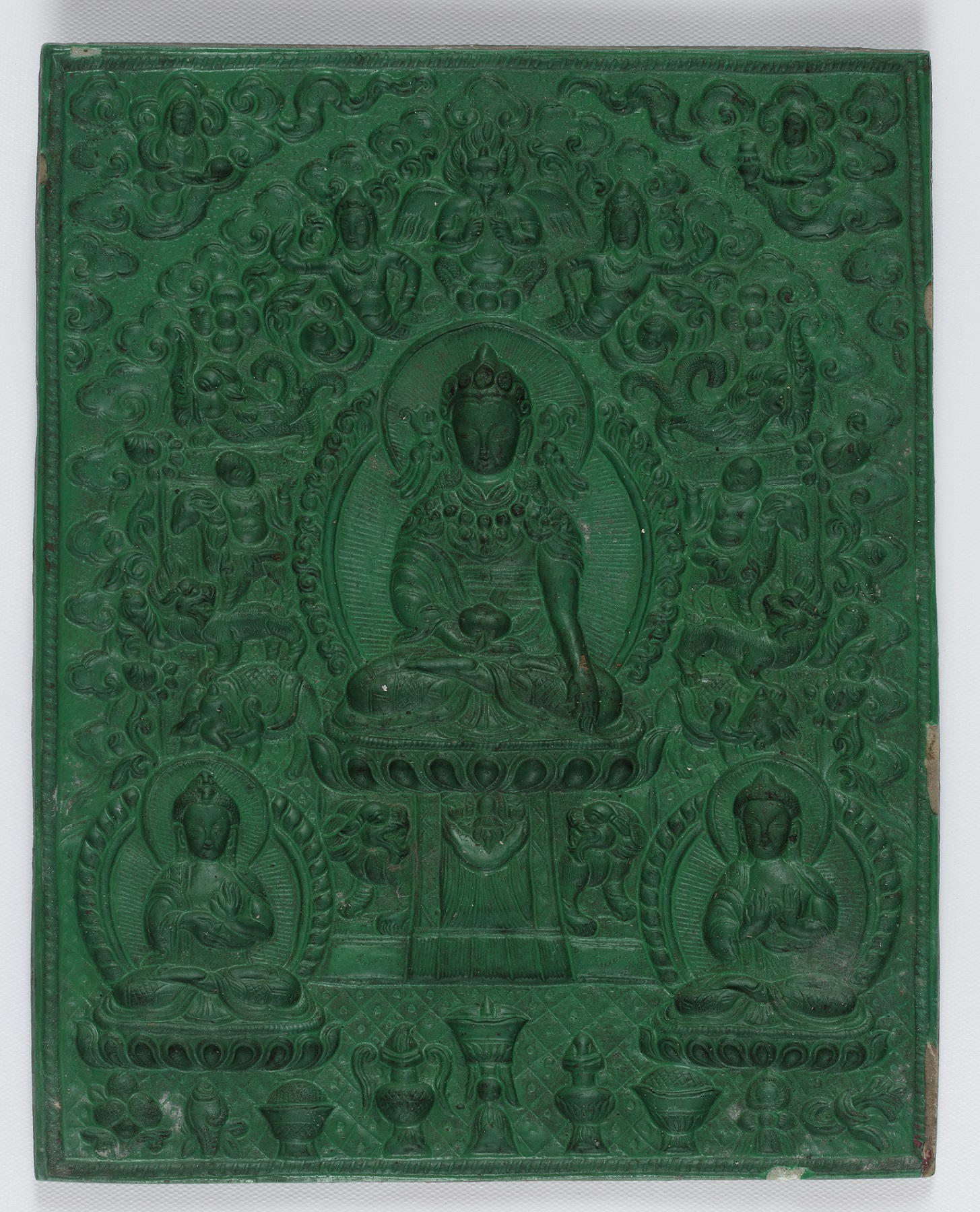

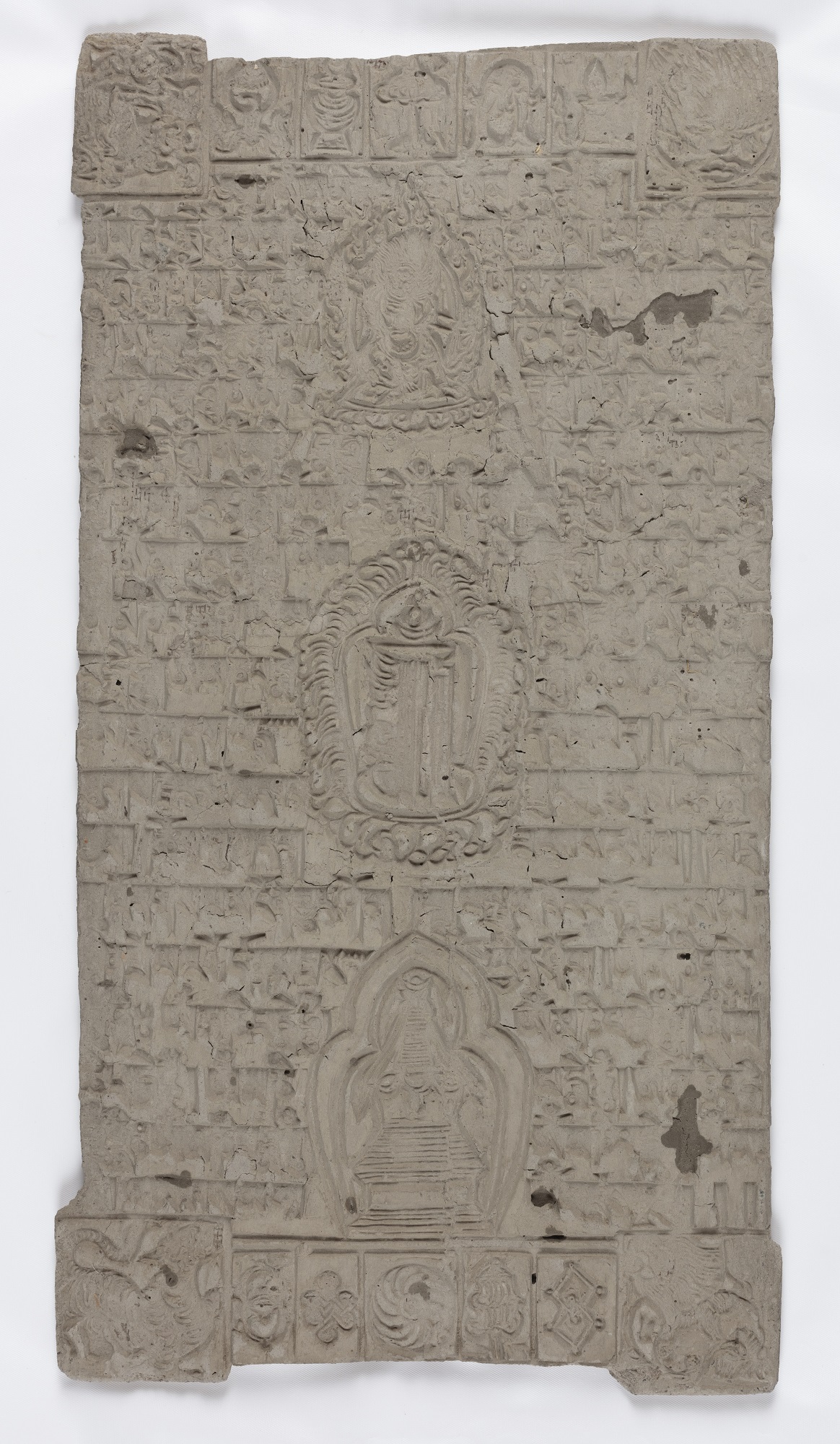

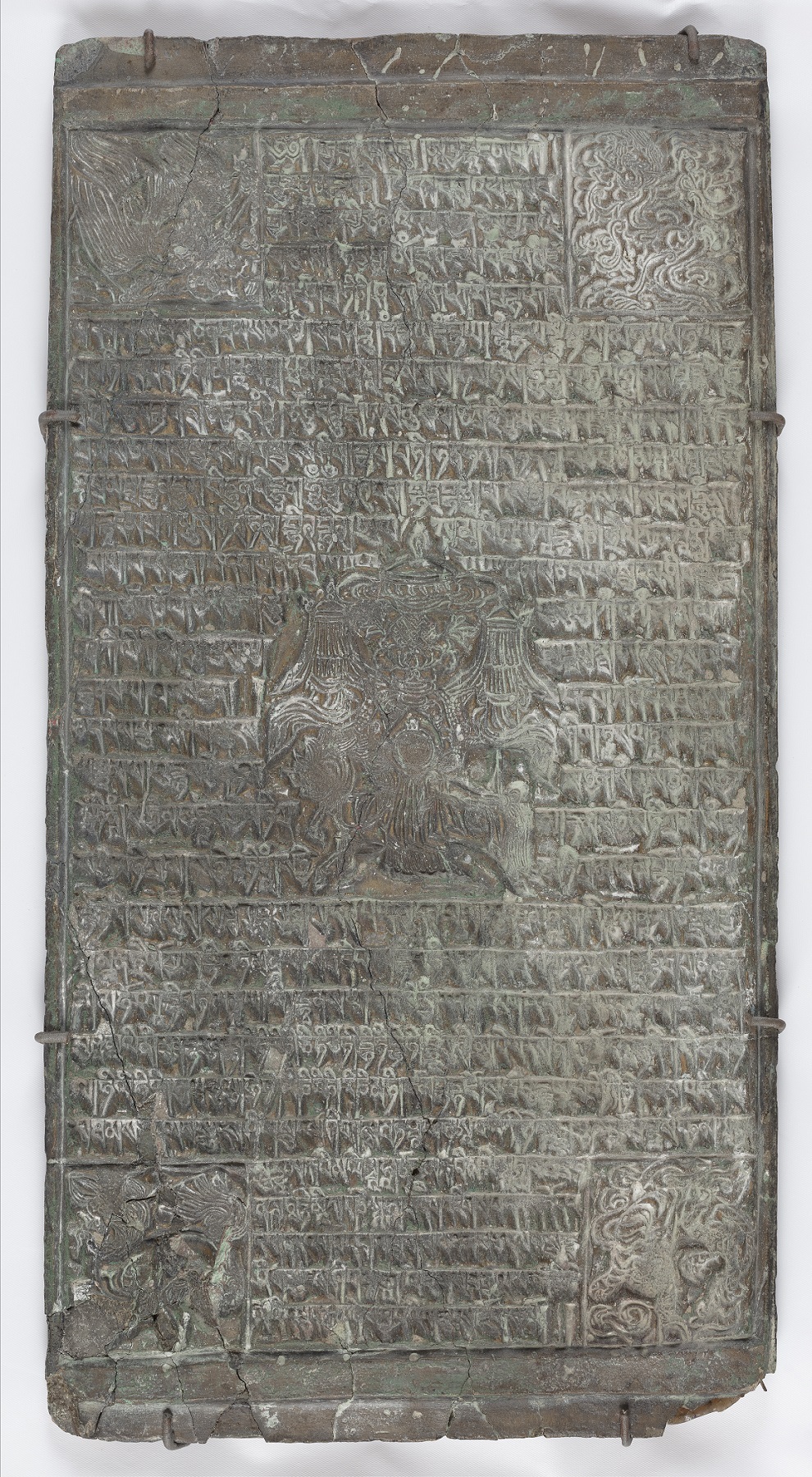

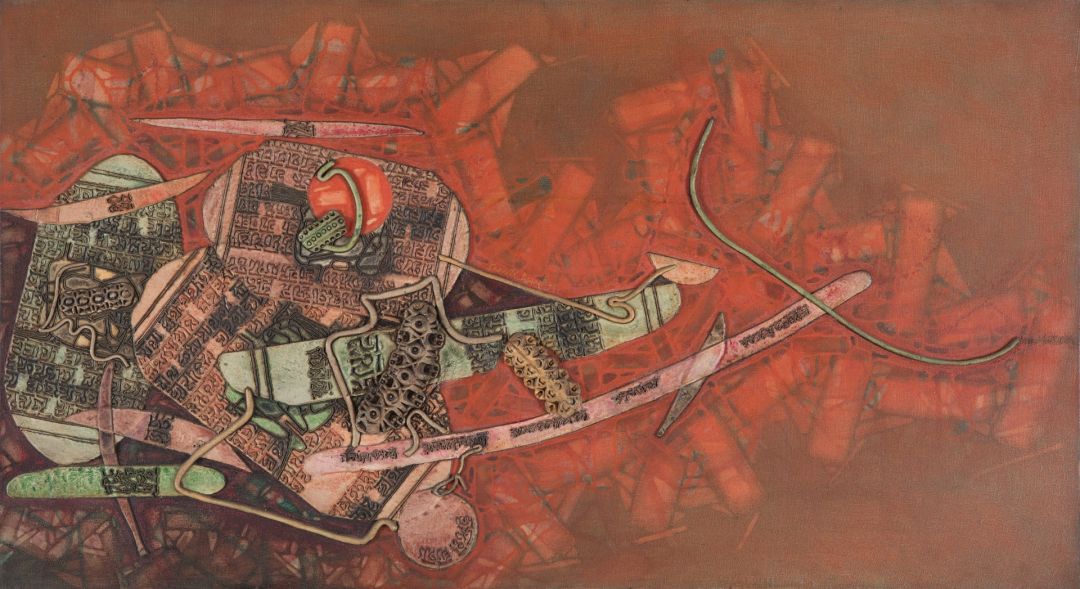

Shanti Dave

Untitled

1974, Oil and encaustic on canvas, 23.7 x 43.2 in.

Collection: DAG

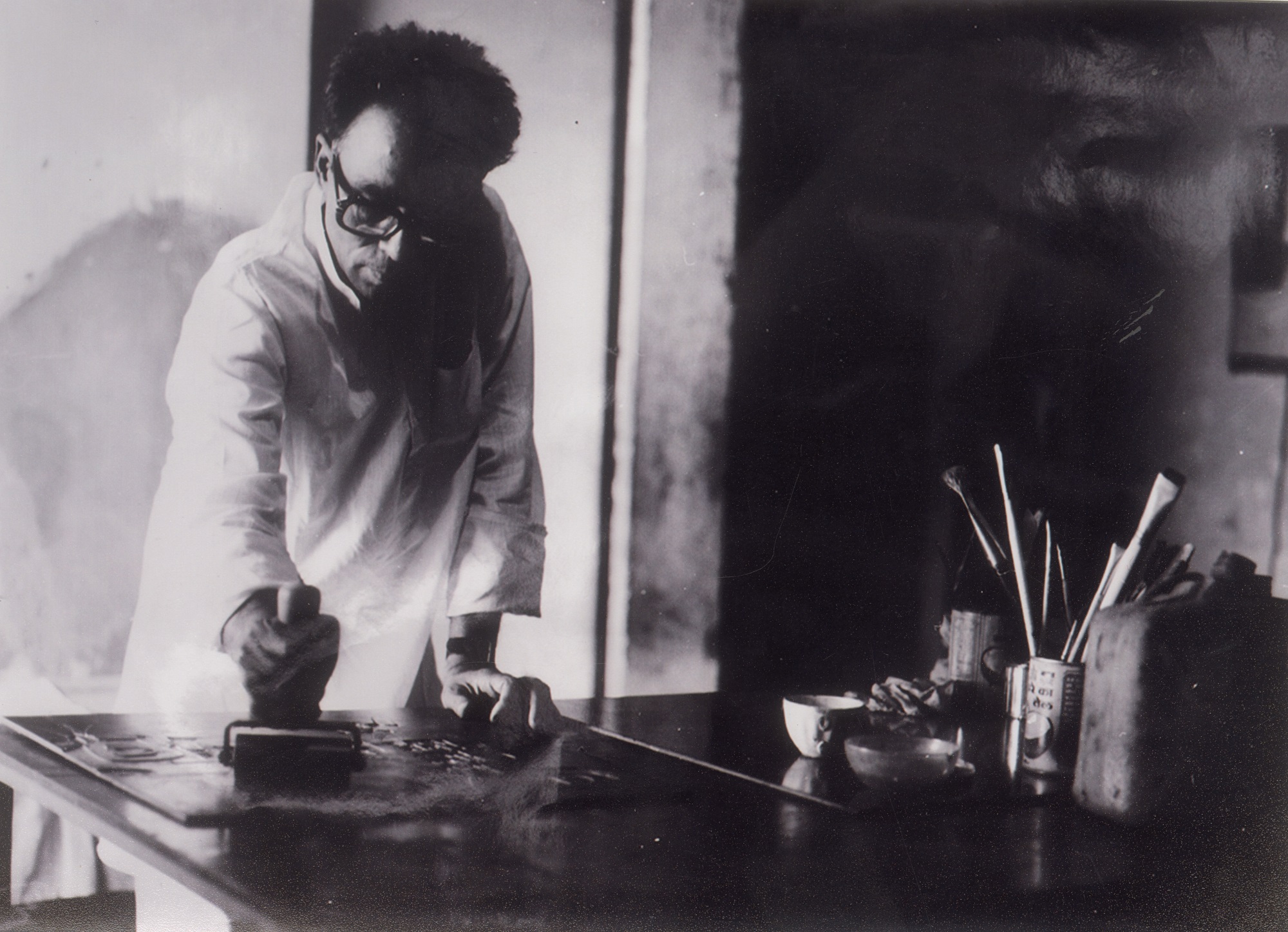

Dave often invoked the past—personal and cultural alike—making ‘memory’ his principal subject matter. Since his first visit to the excavation sites during his college days, archaeological excavation and mnemonic symbolism became his main motif, with symbols of forgotten civilizations, relics of the past, strewn across the large canvases. The viewer is presented with a huge puzzle that looks like a cartographic maze from afar, but upon closer scrutiny, reveals a symbolic richness yet unforeseen, beckoning us to interpret them. ‘To plunge into the depths of the unknown seas, age-old cave paintings, mythological and religious sagas, ruins of hoary monuments fascinated me since my very childhood.’, Dave said in an interview with DAG, on the eve of Manifestations XXXIII. |

|

The works of these two artists are marked by very individualistic, singular styles. Their personal inflections contributed to their painterly visions as well as techniques. What is truly intriguing about their individual style is that the creative life and spiritual world of these individuals were intertwined and hardly separable from one another. For instance, Qadri’s paintings and poems were coextensive with his Yogic meditations. Shanti Dave also strived to fuse the spirits of the forgotten worlds and the painting’s surface, and in this play between the two disparate worlds, Dave considered himself as the ‘madhyam’ who facilitated this fusion. We find out that for each artist who is/was innovatively applying a material technique, there is an urgency to communicate something ineffable, something that resides beyond any language. And their artistic genius consists in devising the techniques that enable them to say the unsayable. |

|

|

|

|