Master 'McBull': Passages from M.F. Husain's LifeThe Editorial Team November 01, 2023 M. F. Husain, also known as Maqbool Fida Husain, and sometimes self-identifying as ‘McBull’, was a renowned Indian painter and one of the most celebrated artists of the twentieth century in India, eventually becoming synonymous with the notoriety of the artworld itself. He was born on September 17, 1915, in Pandharpur, Maharashtra, India, and passed away on June 9, 2011. Ila Pal’s biography of the artist, Husain: Portrait of an Artist attempts to put together a narrative of his life and career, based on extensive interviews with the artist himself. What did the artist have to say about his early influences, his relationship with his fellow-artists and friends and his sources of inspiration through his life? |

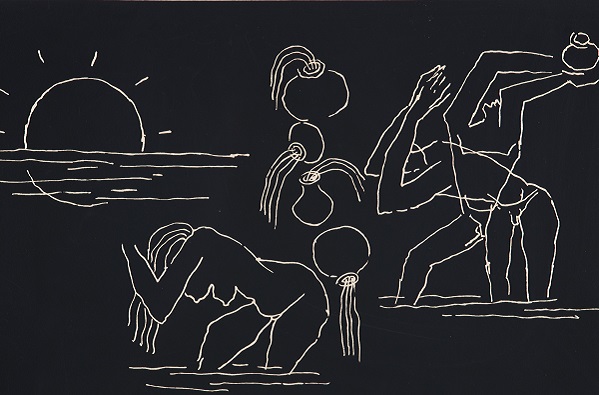

M. F. Husain

Varanasi III

1973, Serigraph on paper, 48.3 x 66.0 cm.

Collection: DAG

|

A painter herself, Pal had accompanied Husain on a sketching trip to Rajasthan in the early 1960s. Rajasthan asserts a primary importance in Husain’s imagination. He was stirred by its eternal cultural richness and varieties of form, but as a quintessentially modern subject, he did not want to reproduce them mechanically, seeking to use tradition as a springboard for exploring new questions about painting, drawing and even cinema. |

|

|

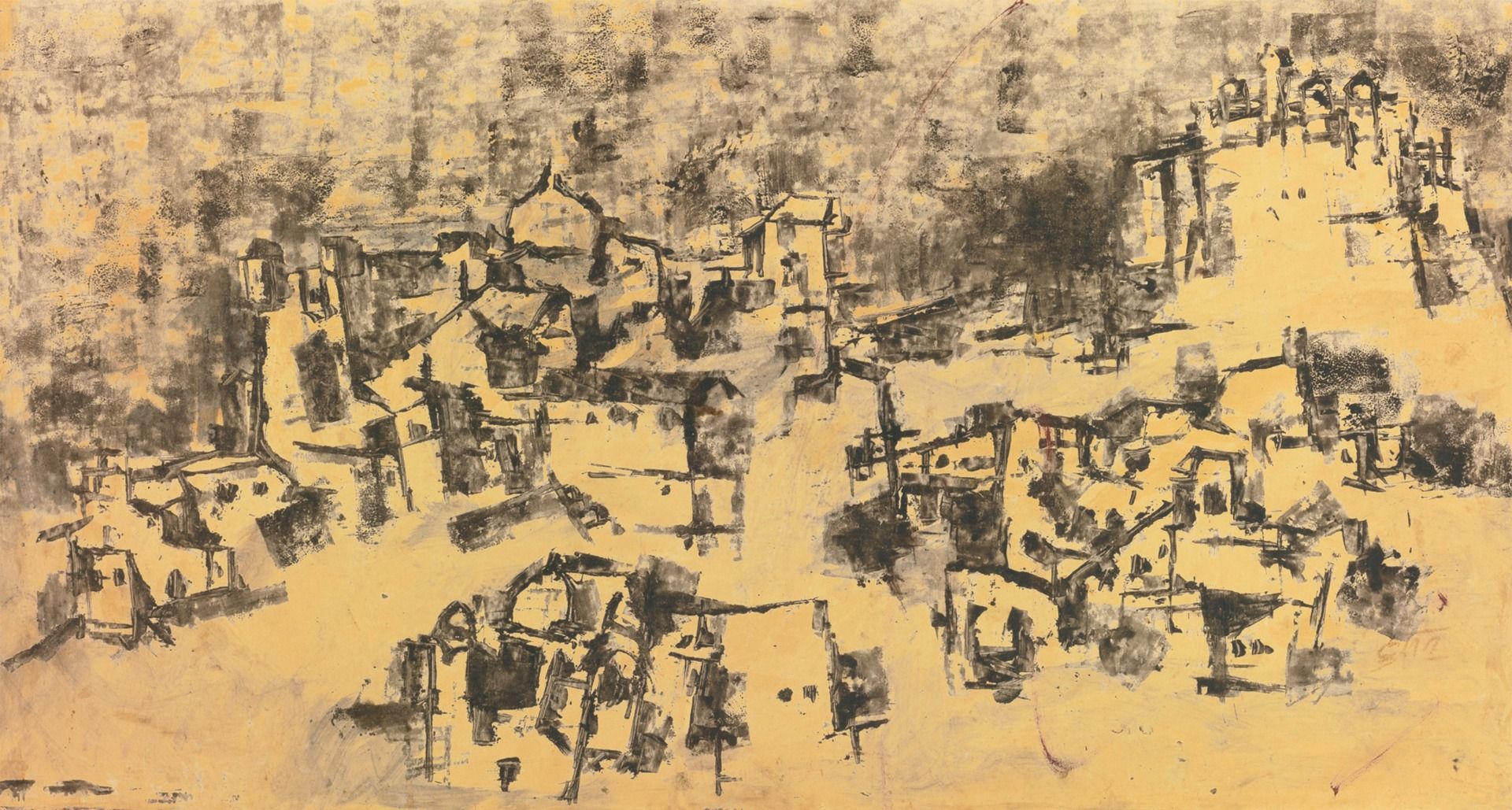

M. F. Husain

Untitled (Rajasthan Landscape)

Oil on paper pasted on board, 65.3 x 121.9 cm.

Collection: DAG

This tension is reflected in the description offered by Pal of the much-misunderstood artist’s exercises in Bundi, as he provokes both wonder and derision, and eventually, admiration, for the near-alchemical transformations he effects with his unique artistic vision:

|

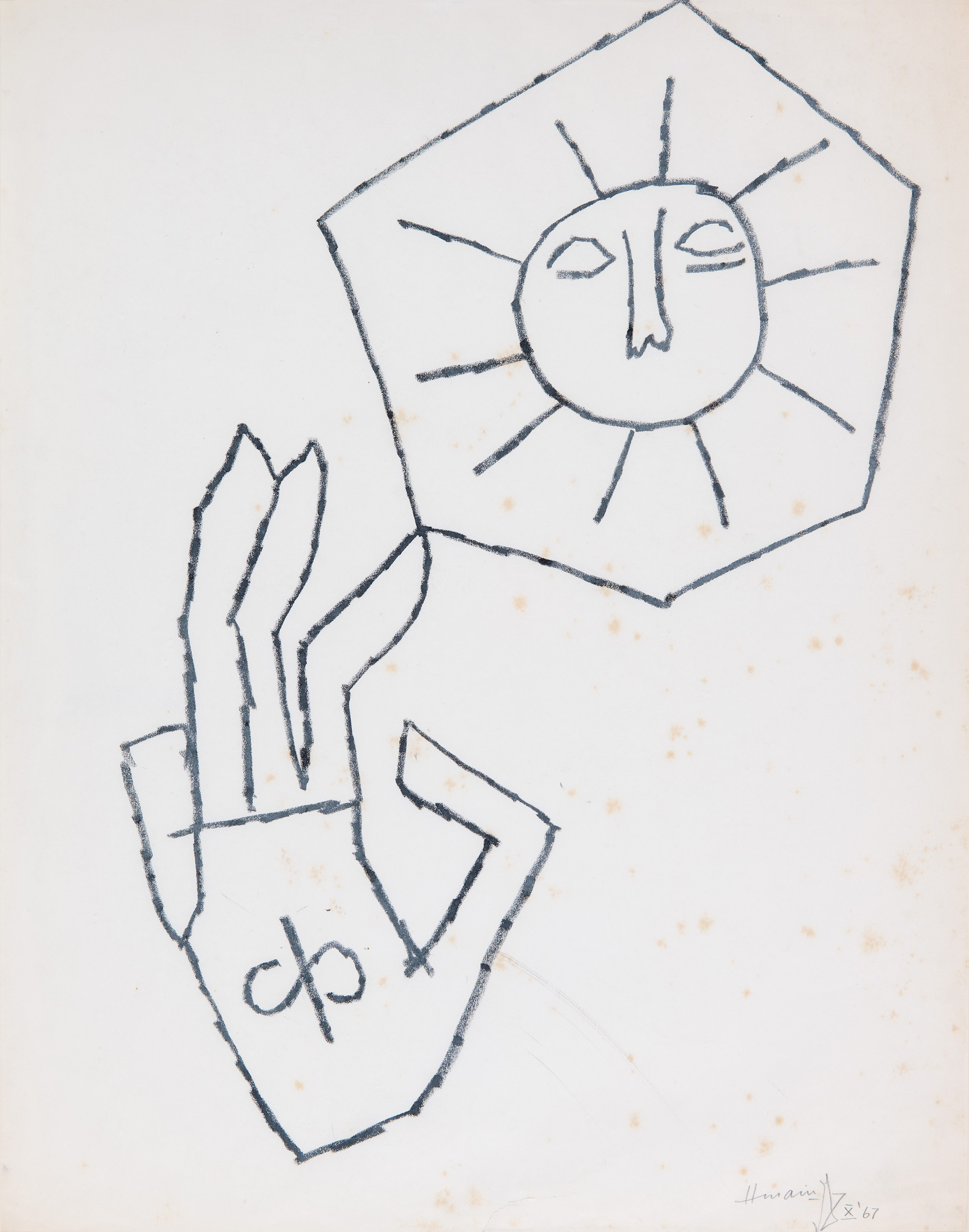

M. F. Husain

Untitled

1967, Pastel on paper, 60.2 X 48.3 cm.

Collection: DAG

Within a couple of days, however, there was a marked change in their attitude. Their amused expressions gave way to perplexed ones. For although Husain was physically present, in their street, sitting across from the idols they worshipped and temples they thronged, what he drew on paper was not quite what was actually there. In effect, reality only acted as a trigger. Husain was drawing upon his visual repertoire, which he had built over decades of seeing, feeling and understanding India—its essence, its ethos.

|

|

Husain was a self-taught artist and began his career as a painter in the 1930s. Throughout his career, he received numerous awards and honours, both in India and internationally, for his contributions to art. He was also a founding member of the Progressive Artists' Group in Bombay (now Mumbai), which played a significant role in the development of modern art in India. Despite his acclaim, Husain was also a controversial figure. In the later years of his life, his work became increasingly political and provocative, leading to controversies and legal issues. He faced criticism and threats from various groups due to his artistic interpretations, especially related to Hindu deities. |

|

|

N. S. Bendre

The Vagabond

Image Courtesy: Wikimedia Commons

Haku Shah

Untitled

Oil on canvas, 61.0 x 61.0 cm.

Collection: DAG

Reflecting on an early, influential figure from outside his family, Husain mentions the sketching expeditions he went on with N. S. Bendre (1910-1992): ‘He had watched Bendre paint his landscapes with awe and admiration, his ‘full-blooded’ brush working vigorously on canvases. Husain also saw him paint The Vagabond that won Bendre the silver medal from the Bombay Art Society in 1934. One day, Bendre came over to meet Fida Husain (Husain’s father). Husain could not recollect exactly what he said to his father, but he remembered one sentence distinctively—‘He is extraordinarily talented. Please let him concentrate on painting.’ Bendre was a talismanic artist-pedagogue of his time, and a founding member of the Baroda group, influencing the work of future modernists like G. R. Santosh, Gulam Mohammad Sheikh, Haku Shah, Shanti Dave and many others. |

M. F. Husain

Lord Ganesha and Mata Parvati

Image courtesy: Public Domain

Abanindranath Tagore

Ganesh Janani

Image Courtesy: Wikimedia Commons

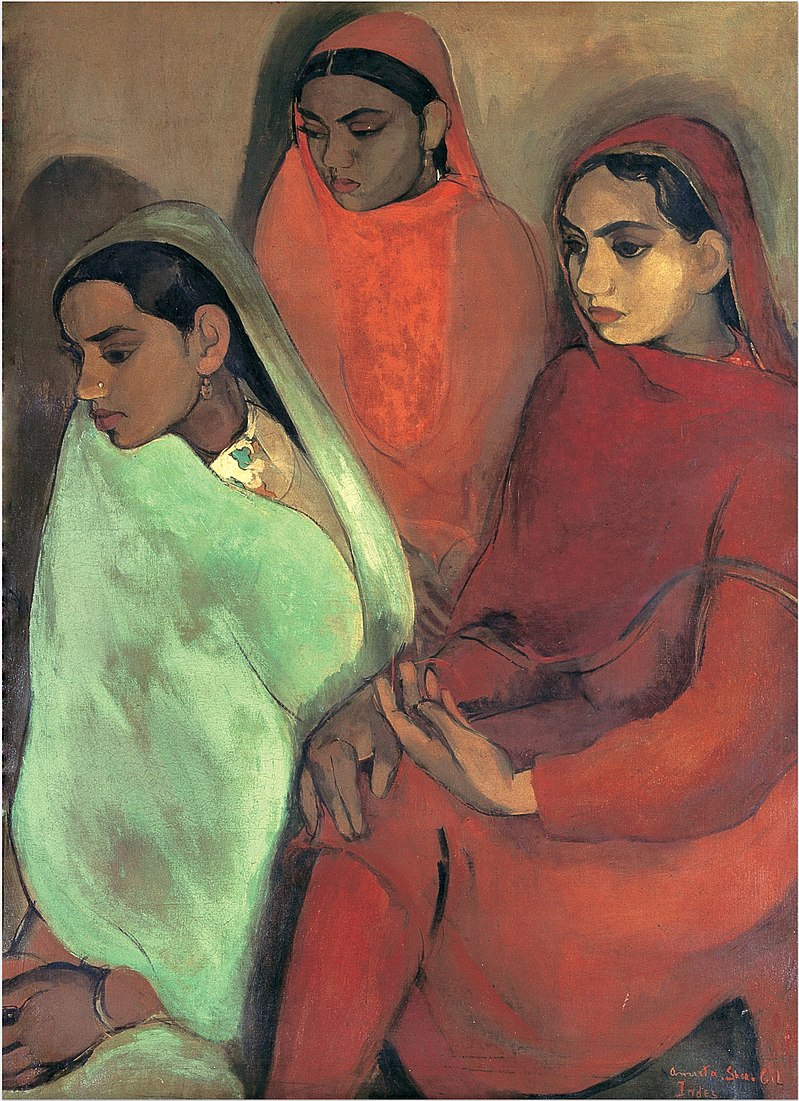

Amrita Sher-Gil

Image Courtesy: Wikiemdia Commons

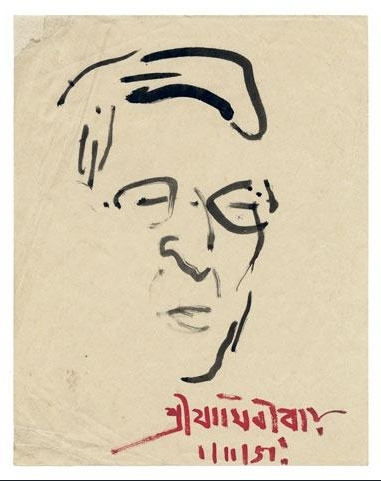

M. F. Husain's sketch of Jamini Roy

Image Courtesy: Public Domain

However, his response to some other major artistic figures from his early life, especially from Bengal, was somewhat cooler: ‘I admired (Rabindranath) Tagore, but his paintings were too subjective, and Gaganendranath Tagore was too meagre to cast an influence. Jamini Roy picked up threads from Kalighat paintings and was brilliant, but for the remaining years, he repeated himself. Amrita Sher-Gil was the only exception. She was modern, her sensibilities were… Even when she went back to Ajanta, she picked up the best—to introduce the two-dimensional aspect. Also, she brought a whiff of the West—Cezanne, Gauguin and Modigliani—but her life was cut short prematurely, so she could not really exert a major influence. We were all groping around, dimly aware of happening all over the world, confused about how to paint in a manner that was not divorced from our traditions and yet expressed our changed perceptions.’ A closer inspection of his oeuvre would suggest a more complex relationship, however. For instance, he painted several Ganesha-Janani images throughout his life, some echoing similar depictions made by artists like Abanindranath Tagore as well. |

|

Husain also illuminates the atmosphere of patronage and (the lack of) institutional support for modern artists like himself and the Progressive Artist’s Group, whose projects, subjects and aesthetic vision was largely misunderstood at the time. |

|

|

K. H. Ara

Untitled

Watercolour and gouache on paper, 35.6 x 47.0 cm.

Collection: DAG

Even though they received the support of organisations like the Indian People’s Theatre Association (I. P. T. A.) or the Progressive Writers’ Group (P. W. G)—all aligned with the political outfit of the Communist Part of India (C. P. I)—major art institutions tended to shun their work. In spite of the pioneering attempts of artists like Nandalal Bose to represent ordinary, peasant lives on Indian canvases, ‘(a)cclaim was not what Krishnaji Howlaji Ara got when he painted Independence Day Procession and sent it to the Bombay Art Society. It was rejected outright, so was a painting by Souza that was dubbed ‘too proletarian’.’ According to Husain, ‘No doubt the Bombay Art Society was active; it had a steadily growing band of collectors too, but it was taking too long to realign itself with the changed aspirations that became obvious when they rejected (F. N.) Souza’s and Ara’s work.’ This would lead to the creation of the Progressive Artist’s Group in 1947. |

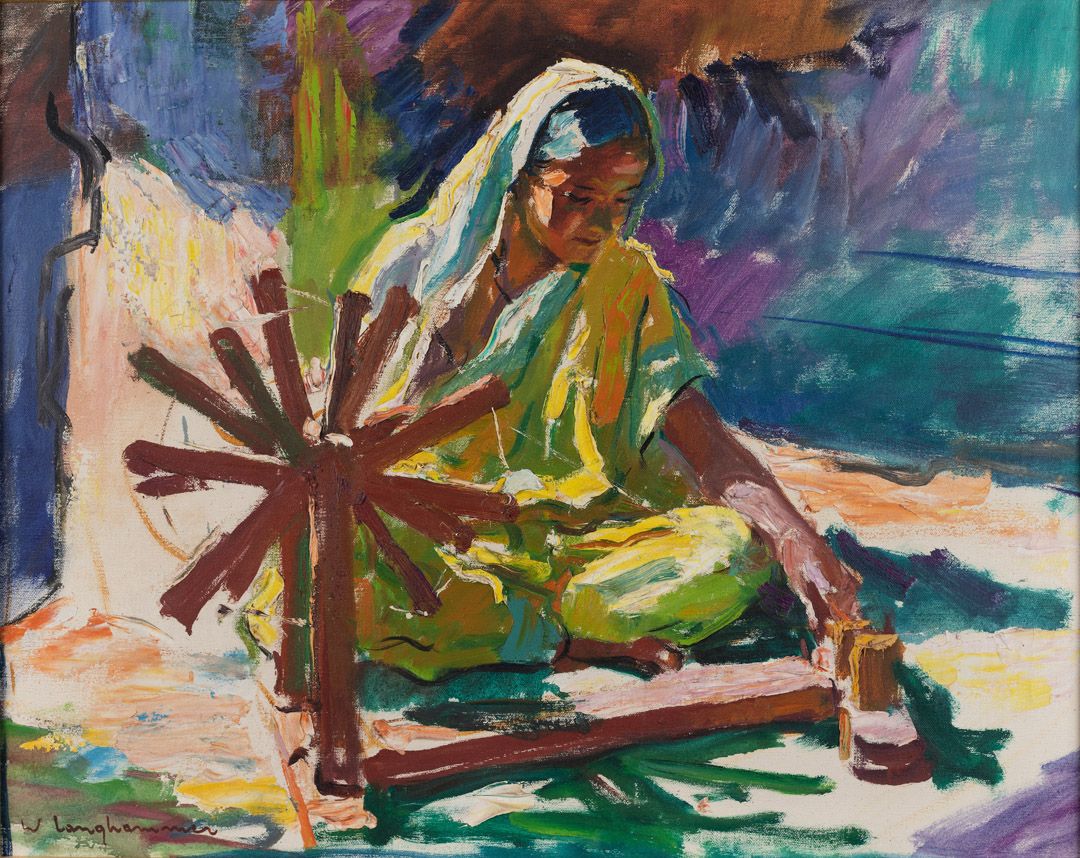

Walter Langhammer

Untitled (Portrait of a Woman at a Spinning Wheel)

Oil on canvas, 57.7 x 71.1 cm.

Collection: DAG

Comparing the openness of the cultural organisations allied with the C. P. I. to others, Husain says, ‘the attitude of our keepers of antiquity like Dr. Moti Chandra and Rai Krishnadas was appalling. While foreigners like E. Schlesinger, Rudolf von Leyden and Walter Langhammer, who had come to India as refugees and were just finding a foothold, sold their possessions to help us, these ‘stalwarts’ who should have encouraged us, treated us like pariahs… On the other hand, there were people like Dr Homi Bhabha, then head of the Tata Institute of Fundamental Research (TIFR), who started collecting modern art for his institution. He met with a lot of opposition, both within and outside parliament… All said and done, but for the support from (Emanuel) Schlesinger, Leyden and Dr Herman Goetz of the Baroda Museum, it would have been difficult to sustain the tempo the (modern art) movement.’ Husain’s narrative is also a source for learning more about these early collectors and influencers of Indian modern art. Speaking about Schlesinger, he says, ‘(he) would drop in at my chawl, pick up a painting and leave some money in Shafaat’s (Husain’s son) hand. Astute and unassuming, he was my first collector. He arrived in India as a penniless refugee and founded a pharmaceutical company. The first thing he did, once he was on his feet again, was to start buying paintings.’ |

|

What about his friends and fellow-travellers? Husain remained close with his cohorts, especially those from his early years with whom he started the Progressive Artist’s Group. In his conversation, whenever he used the pronoun ‘we’ to talk about a group show, it would include his six closest artist friends—S. H. Raza, Bal Chhabda, Tyeb Mehta, Ram Kumar, Akbar Padamsee and V. S. Gaitonde. |

|

|

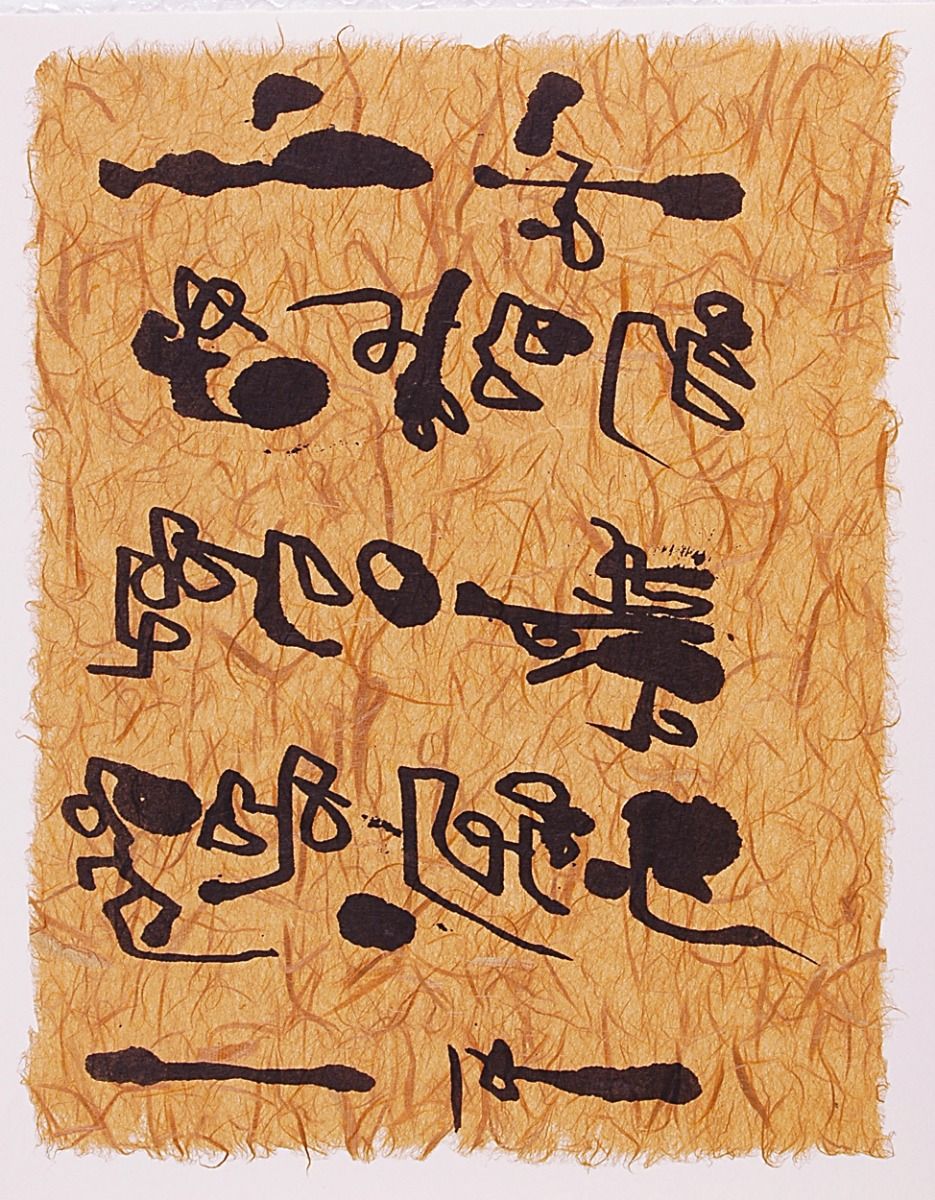

V. S. Gaitonde

Untitled

Serigraph on handmade paper pasted on handmade paper, 29.2 x 22.9 cm.

Collection: DAG

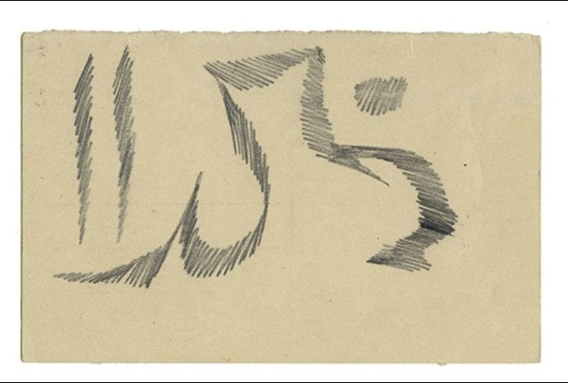

M. F. Husain

Untitled

Image Courtesy: Public Domain

However, his relationship with all of them went through phases of tension or even hostility, exacerbated by a state of competition between them, which would also serve to push each other’s work through honest critique. With some figures like Ram Kumar, Husain also shared literary alliances, as both maintained a writerly practice deep into their painting careers. Husain usually wrote in Urdu (he was also a prolific letter-writer), using calligraphic forms in his paintings as well, while Kumar wrote short stories in the emergent modernist idiom of his time. ‘When it comes to paintings, we turn into bitter rivals’, he says. Pal is unable to recover the precise nature of these relationships, however, as she writes, ‘I still know little of Husain saheb’s relationship with his peers except that he went seeking Bal Chhabda like a magnetic pole its opposite; went to Ram Kumar like a bird returning to its nest; loved and respected Tyeb as Tyeb respected him, against whom Tyeb would not speak, however great the provocation, and Husain would keep seeking his assurance and approval, however difficult to get. Akbar Padamsee, he thought, ‘most brilliant and articulate, who mind is very sharp’, so sharp that sparks flew. Husain admired Gaitonde’s painterly qualities more than his own. He found Swaminathan to be ‘an astute judge, and exceptionally adroit mind,’ but whose corridors he treaded apprehensively.’ |

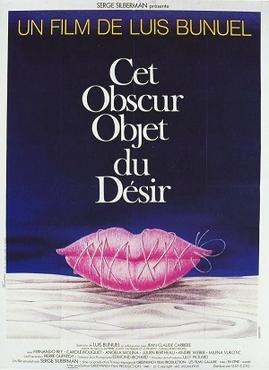

M. F. Husain

That Obscure Object of Desire 21

Graphite and watercolour on paper, 50.8 x 36.8 cm.

Collection: DAG

Husain excelled in marrying influences from disparate sources; mixing up elements from Indian mythology, regional artistic traditions and national forms with global, especially European, works. Cinema remained a lifelong object of wonder for Husain, from his youth when he tried to paint scenes from films he had seen in a local theatre, to his own experiments with filmmaking in the 1960s, and eventually, towards the end of his life, producing major productions with established stars from Bombay cinema, like Madhuri Dixit. He liked to watch films without any preconceived notions about them—taking in European arthouse cinema in the same breath as commercial, popular films made in Bombay. Talking about a famous work by him, Pal writes, ‘That Obscure Object of Desire, painted in 1979, had its roots in the Mahabharata. It was inspired by the film bearing the same name, made by Louis (sic) Bunuel, whom Husain considered a film-maker of highest importance. ‘I had been working on the Mahabharata series and then I saw Bunuel’s film. That gave me a clue how to turn to contemporary things.’ In a very subtle sense, both the Mahabharata series and ‘That Obscure Object of Desire portrayed the continuous struggle between the good and the evil that goes on within us.’ |

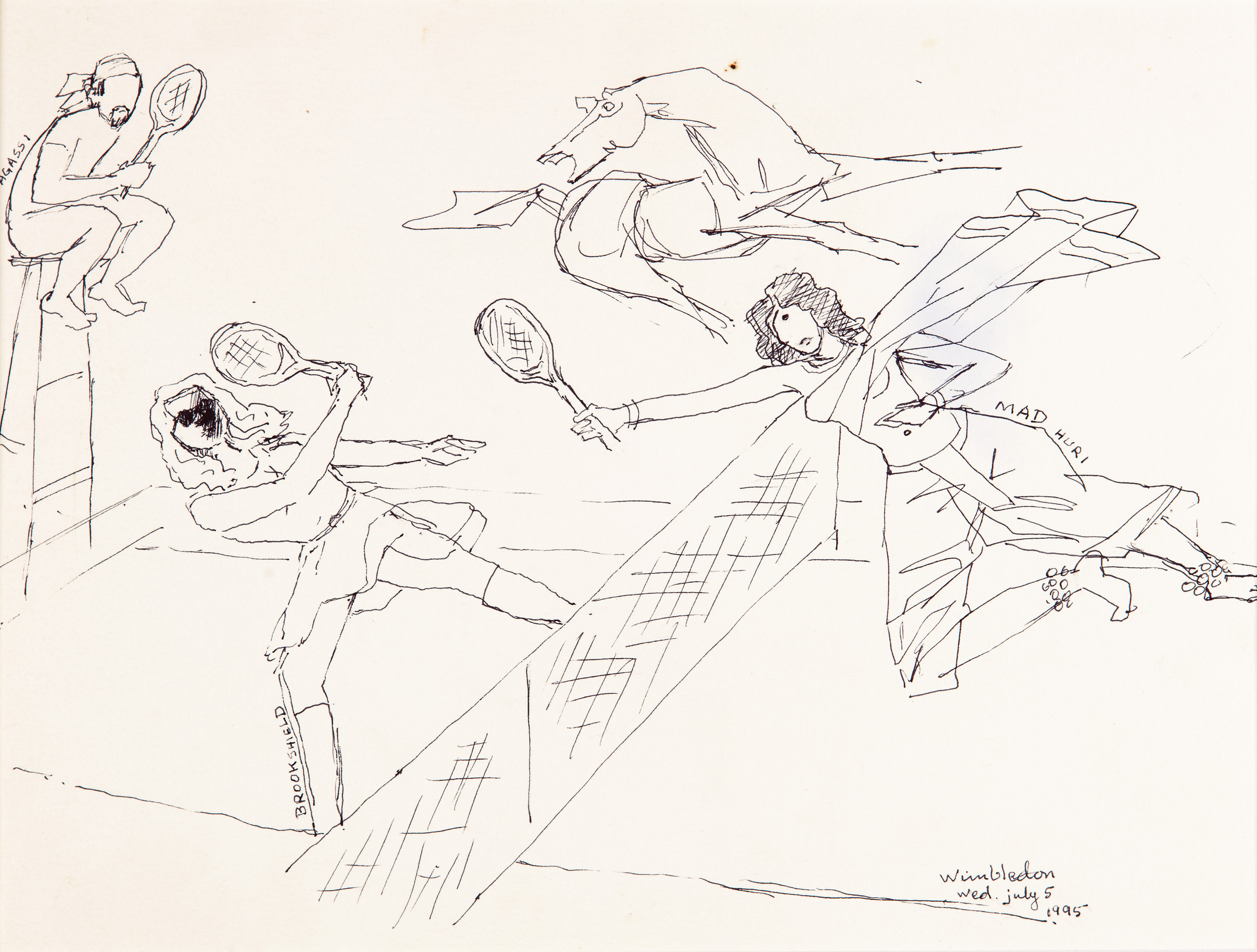

M. F. Husain

Untitled

1995, Ink on paper, 22.9 x 30.5 cm.

Collection: DAG

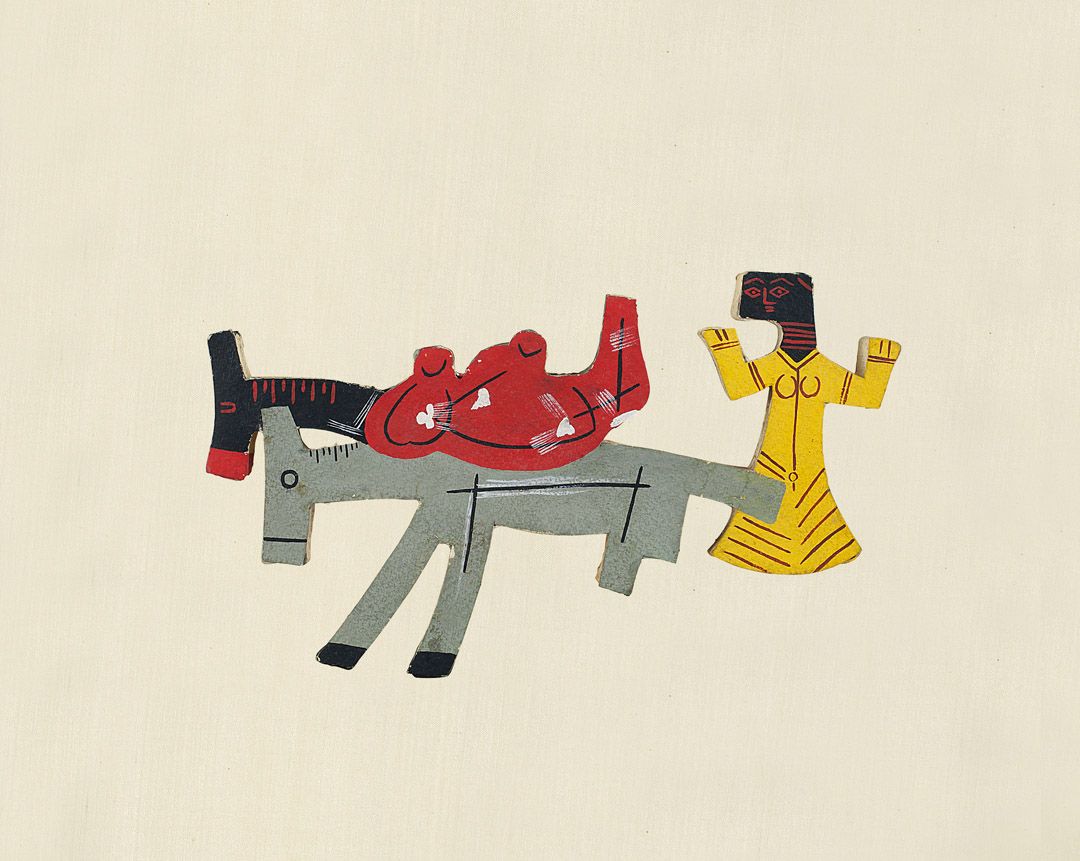

M. F. Husain

Kumhar (Toy Series)

1975, Gouache on handmade paper laid over cloth-bound mount board, 18.3 x 33.0 x 2.5 cm.

Collection: DAG

M. F. Husain

Untitled (Toy Horse)

1988

Image Courtesy: Public Domain

Husain’s playful, magpie-like imagination extended to making toys, designing furniture (which he also did professionally) and inventing myths about things he saw around him, which could also include the sport of lawn tennis. Nonsense and mythmaking is as sacred a source for modern art as it is for the modern subject in general, which finds in these imaginative plays an access to dwell in a world of their own poetic making, against the burden of an official knowledge of an always already well-known, rational world. Pal reports Husain’s fantastical origin story of the sport, inspired by his dedication to the Wimbledon tournament: ‘The British conceived the most amazing of games. During Queen Victoria’s time, rich Englishmen would meet at countryside clubs for evening tea. Summer environment—open air—vast green lawn—five o’clock and time for high tea—polite conversation—forced smiles… It is here in the green lawns that a happy-go-lucky Englishman snatched a marigold from the basket-like hat of an Englishwoman and began throwing it in the air. Another friend ran and they began throwing the flower back and forth between them. In this confusion, an old lady’s hairnet got stuck in a bush. In panic she walked across and the net unwound slowly only to have the other end stuck in another bush. Meanwhile the players kept throwing the flower over and across the net. This is where the game of tennis was born. The marigold flower became the ball, the old lady’s hairnet became the net—and the lawn was already there.’ As Husain progressed further in into his career, and spread himself thin over several projects, this imagination would repeatedly come to his aid as he translated its play into a practice that defined an era. |