MARCH TO FREEDOM: REFLECTIONS ON INDIA'S INDEPENDENCE

MARCH TO FREEDOM: REFLECTIONS ON INDIA'S INDEPENDENCE

MARCH TO FREEDOM: REFLECTIONS ON INDIA'S INDEPENDENCE

|

MARCH TO FREEDOM: REFLECTIONS ON INDIA'S INDEPENDENCE Indian Museum Kolkata, 23 July - 18 Sep 2022 Exhibition by DAG Sudhir Khastgir Untitled, 1946 Watercolour on handmade paper |

|

March to Freedom re-interprets the well-known story of the Indian freedom struggle and anticolonial movement through works of art and some historic artefacts. Drawn from the collections of DAG, they range from eighteenth and nineteenth century European paintings and prints, to lesser known works by Indian artists that merit greater recognition, alongside some iconic pieces. Rather than following the usual chronological path, the story is structured around eight themes. Each represents one arena, or stage, on which the anti-colonial struggle took place, to expand the story beyond politics, politicians, and battles (which also feature). Conceived to commemorate and celebrate the 75th anniversary of India’s independence, this visual journey seeks to do more. For even as we remember the struggles, the sacrifices, and the stories, such anniversaries are also occasions for reflection, including upon the scholarship that has developed on South Asian history. Some of the latter may be familiar to academics, or those with special interests. For most of the rest of us, our knowledge of this past is derived in large part from hazy memories of school lessons, which change from one generation to the next, and are influenced by concurrent national politics. We also learn from narratives on offer through public channels or in the media, to mark moments of national remembrance or controversy. |

|

Stella Brown Merry Go Round Oil on canvas |

|

BATTLES FOR FREEDOM India’s independence was hard won, and fought for. It is also celebrated because it showed the power of non-violent action, a strategy that continues to inspire us, and others around the world. Not all the artworks here show battles; some show the landscapes of battle, reminding us that there was more involved than just the conflict itself, or its winners and losers. Battles also impact, and are shaped by, the people and lands in which they are fought. Stories of battle often feature heroes and villains. Sometimes, these are matters of perspective. We think of the British as the main opponents in these battles. In fact, there were many competing parties, and varied reasons for the conflicts that took place. Much of it was fuelled by quests for power and wealth, on all sides. They were also linked to international politics, the desire to control trade networks, and capture markets. |

|

Thomas J. Barker 'The Relief Of Lucknow & Triumphant Meeting of Havelock, Outram, & Sir Colin Campbell, November 1857' Engraving, tinted with watercolour on paper |

Henry Singleton

The Last Effort and Fall of Tippoo Sultaun, 1802

Engraving, tinted with watercolour on paper

Thomas J. Barker

The Relief Of Lucknow & Triumphant Meeting of Havelock, Outram, & Sir Colin Campbell, November 1857

Engraving, tinted with watercolour on paper

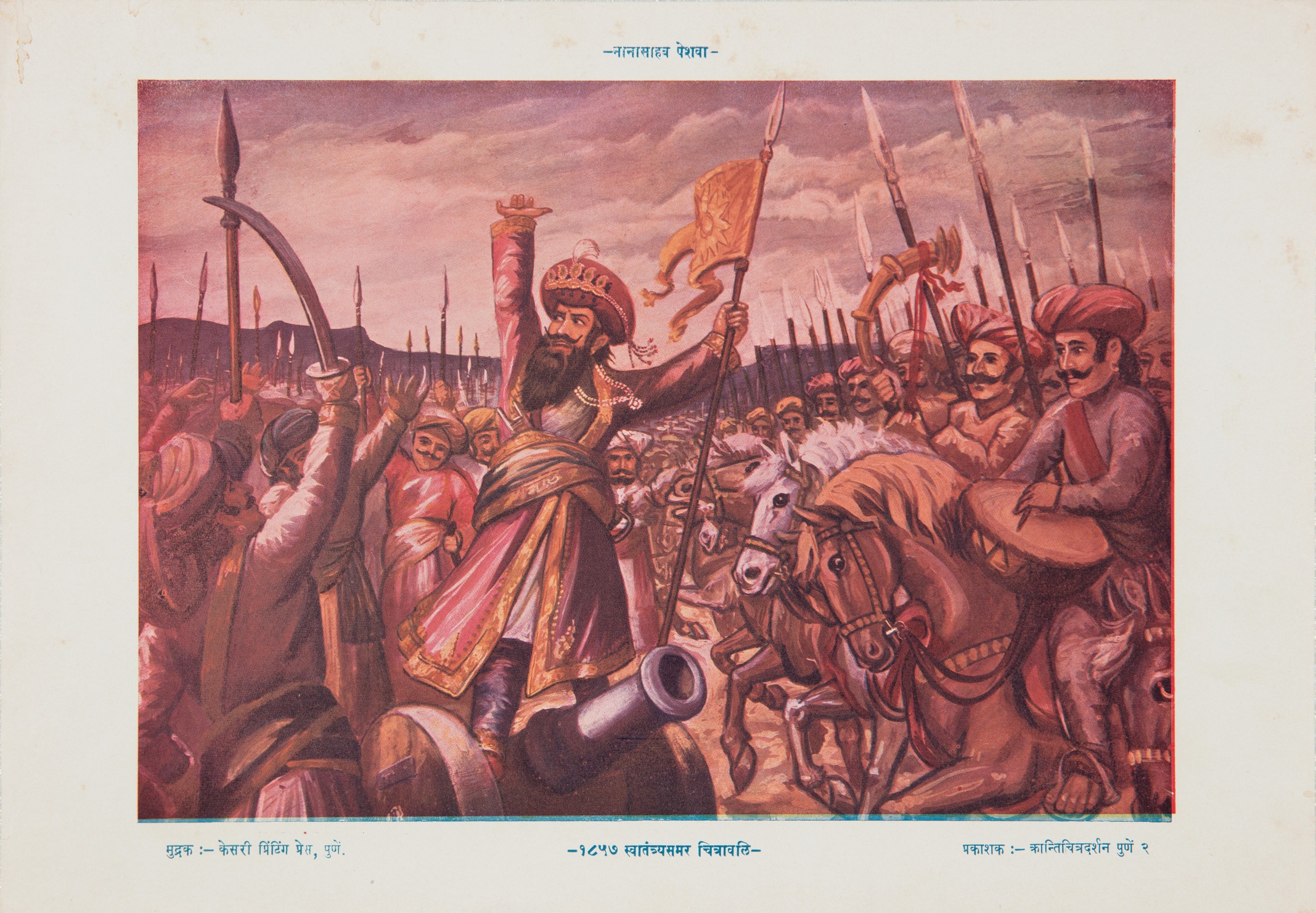

Unidentified artist

Nanasaheb Peshwa, 1857

Offset print on paper

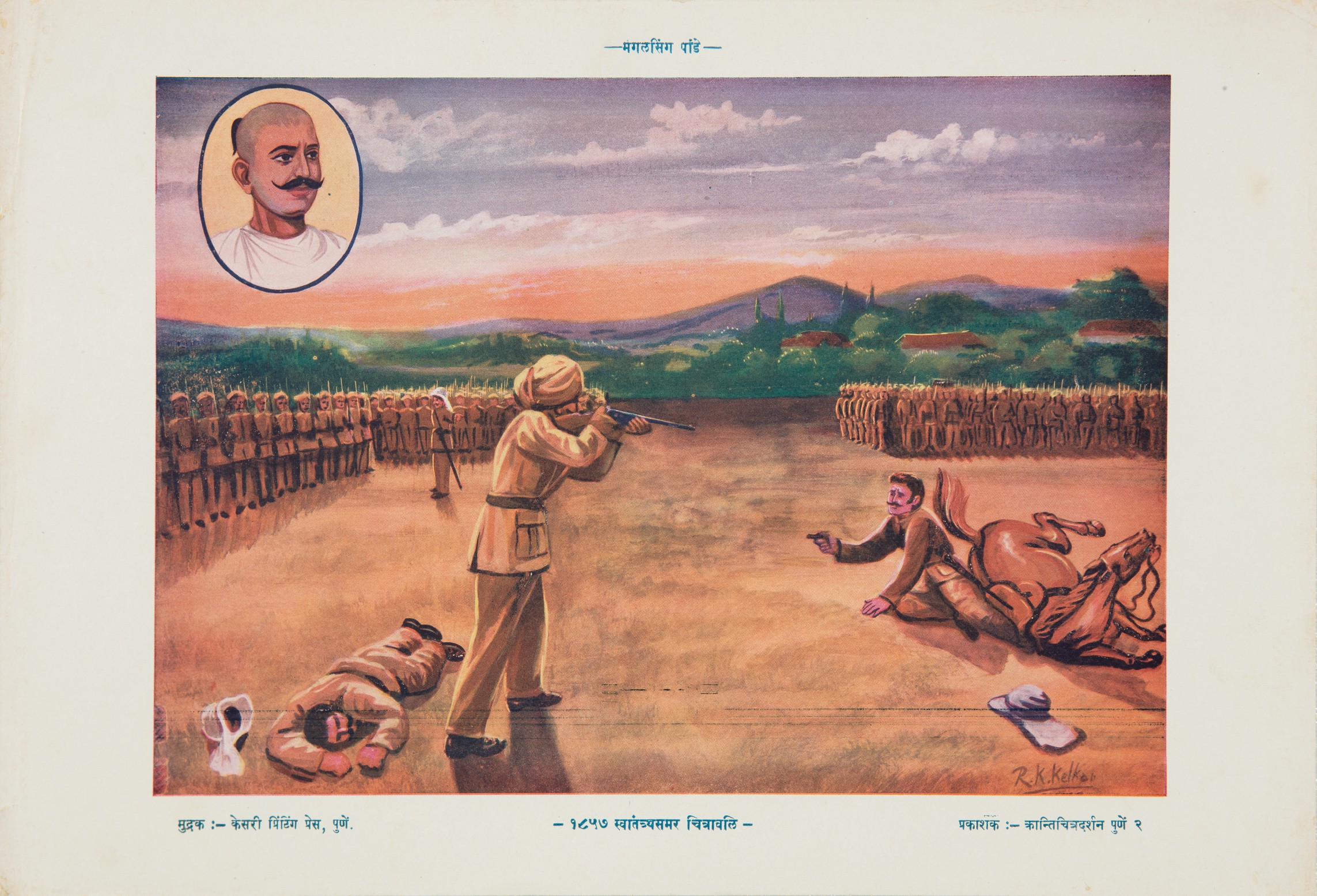

R.K Kelkar

Mangal Singh Pandey, 1857

Offset print on paper

Showing Tipu Sultan and his followers on the back foot before the advancing enemy, this scene is full of drama and energy. It is almost like a snapshot of real events. Indeed, this style is called ‘history painting.’ Contrasting starkly in style and iconography, the indigenous prints from the 1900s offer an Indian view of the events of 1857. Nana Sahib, 14th Peshwa of the Maratha empire, accused the East India Company of breaking financial arrangements that they had agreed. Mangal Pandey is symbolic of the many infantrymen in the Company’s armies in India who rebelled. By forcing soldiers to bite into rifle cartridges greased in cow or pig fat (banned to Hindus and Muslims for different reasons), the British upset Company troops from both communities. |

Thomas Anbury

View within the Northern Entrance of Gundecotta Pass

Francis Swain Ward

Fortress of Gwalior

William Hodges

A View of Chinsura, the Dutch Settlement in Bengal

|

TRAFFIC OF TRADE Water — and our ability to navigate it — has connected people across continents through time. Whether motivated by a spirit of adventure and exploration, better opportunities for a secure life, finding new markets for trade, or by accident, the waterways of the world have brought the world to our shores, and taken India to the world. Viewed this way, our history is that of our waters: what comes in and goes out with the tides. The seas brought Roman merchants and Arab traders in search of spices and textiles, and later, European commercial companies. Fleets of ships and boats made it possible to establish colonies, and to exploit the resources of faraway lands. Fortunes have been made and lost by water. |

|

R. Dodd Portrait of an East Indiaman sailing from Madras Aquatint, tinted with watercolour on paper |

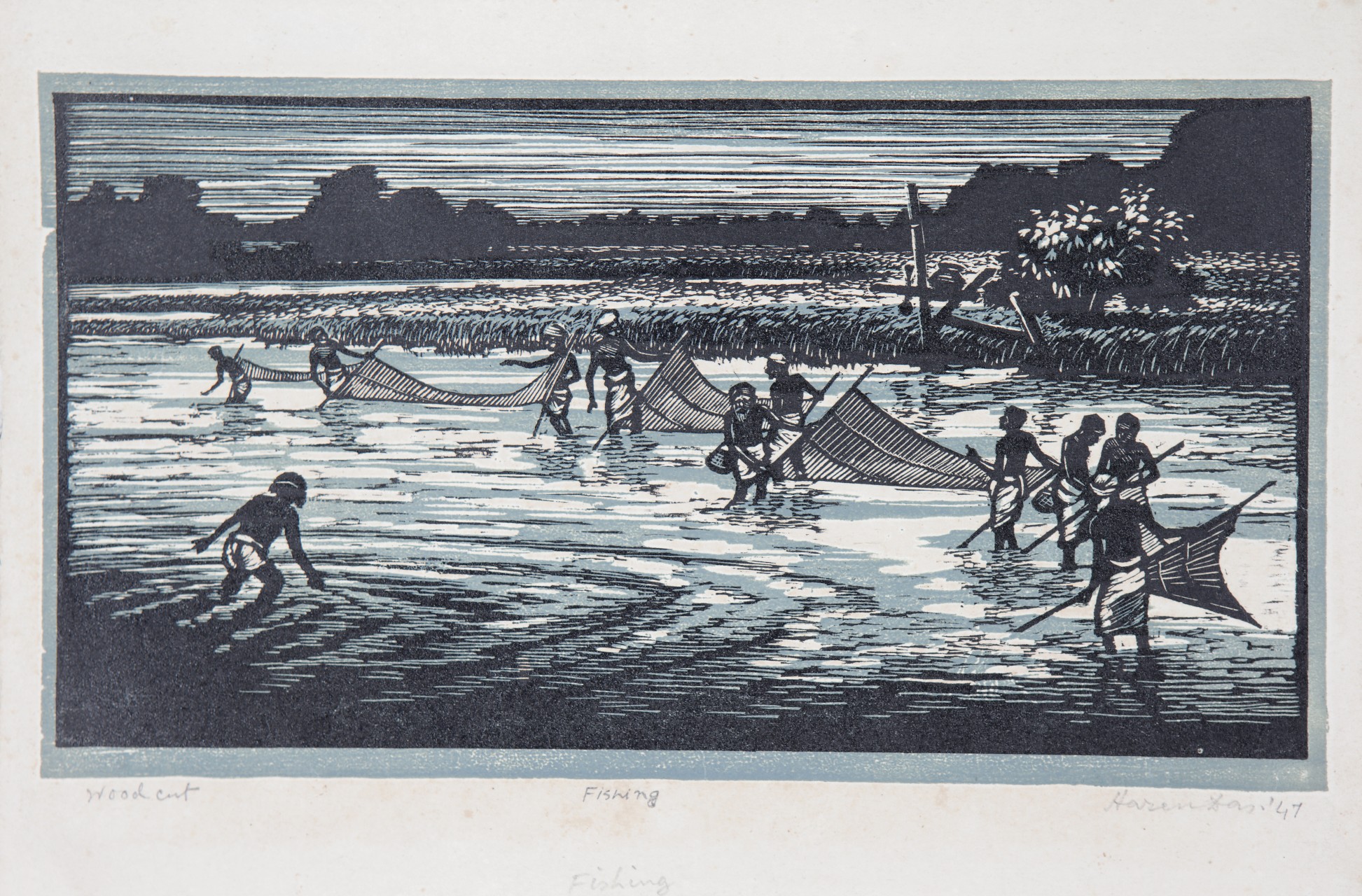

Haren Das

'Fishing'

Woodcut on paper

Biren De

Untitled

Watercolour on paper

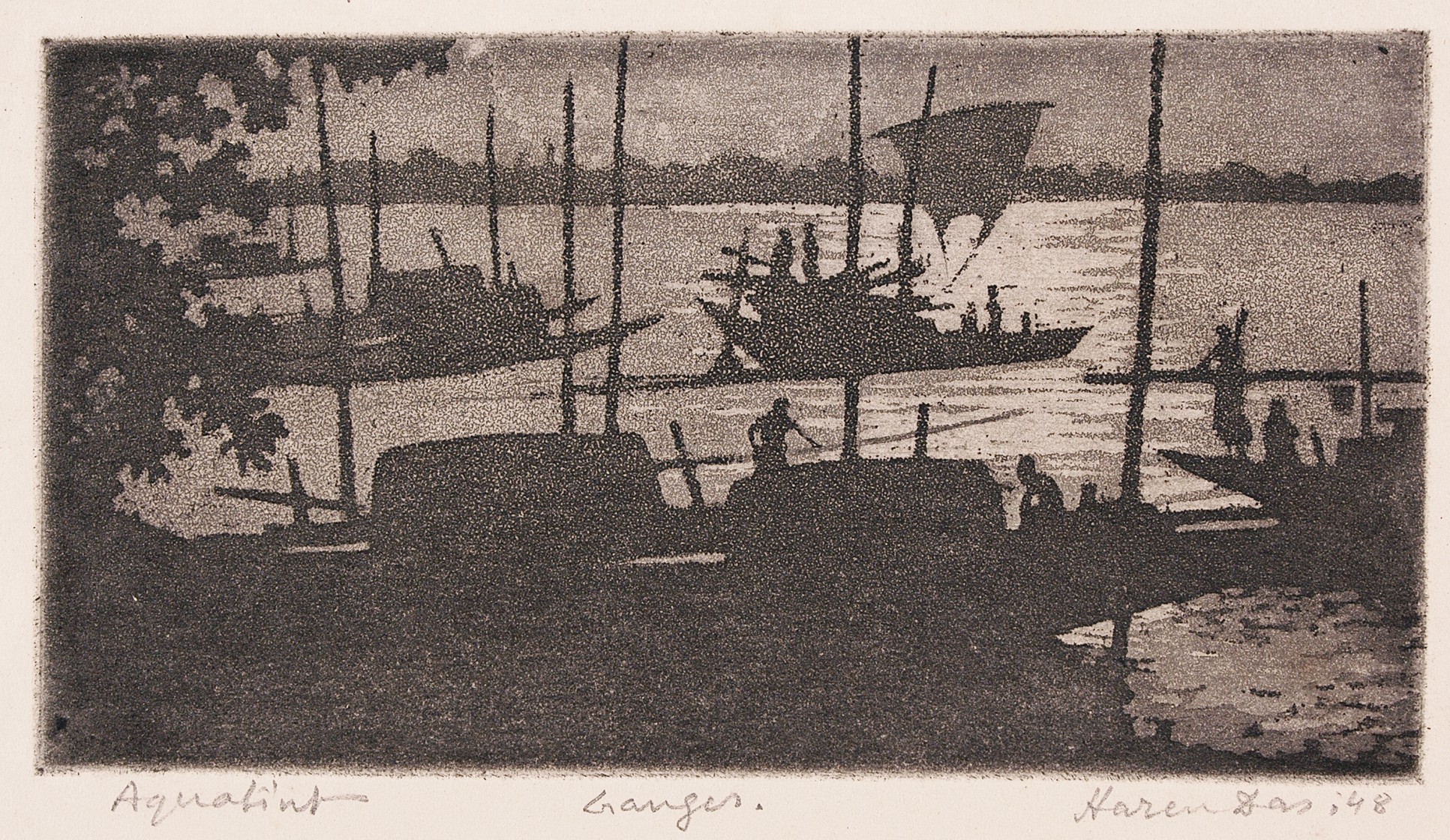

Haren Das

Ganges

Aquatint on paper

Charles Walters D'Oyly

Untitled

Oil on canvas

Charles D'Oyly

Garden Reach

Lithograph on paper

These pictures evoke the quiet, solitude, and labour that typify life on the water. They also remind us of ‘ordinary’ people and lives, and the major changes to historic trade networks that independence caused, as much as the colonial regime before it. The artists, Haren Das and Biren De were both born in what is now Bangladesh, but we think of them as Indian. Haren Das in particular is known for being inspired by memories of undivided Bengal. Contrasting with the style and mood of the prints, European academic paintings tended to focus more on the expanse of the landscape, where people occurred almost like decorative additions. |

Unidentified Thanjavur artist

Accountant and wife

Unidentified Thanjavur artist

Silk weaver and wife

|

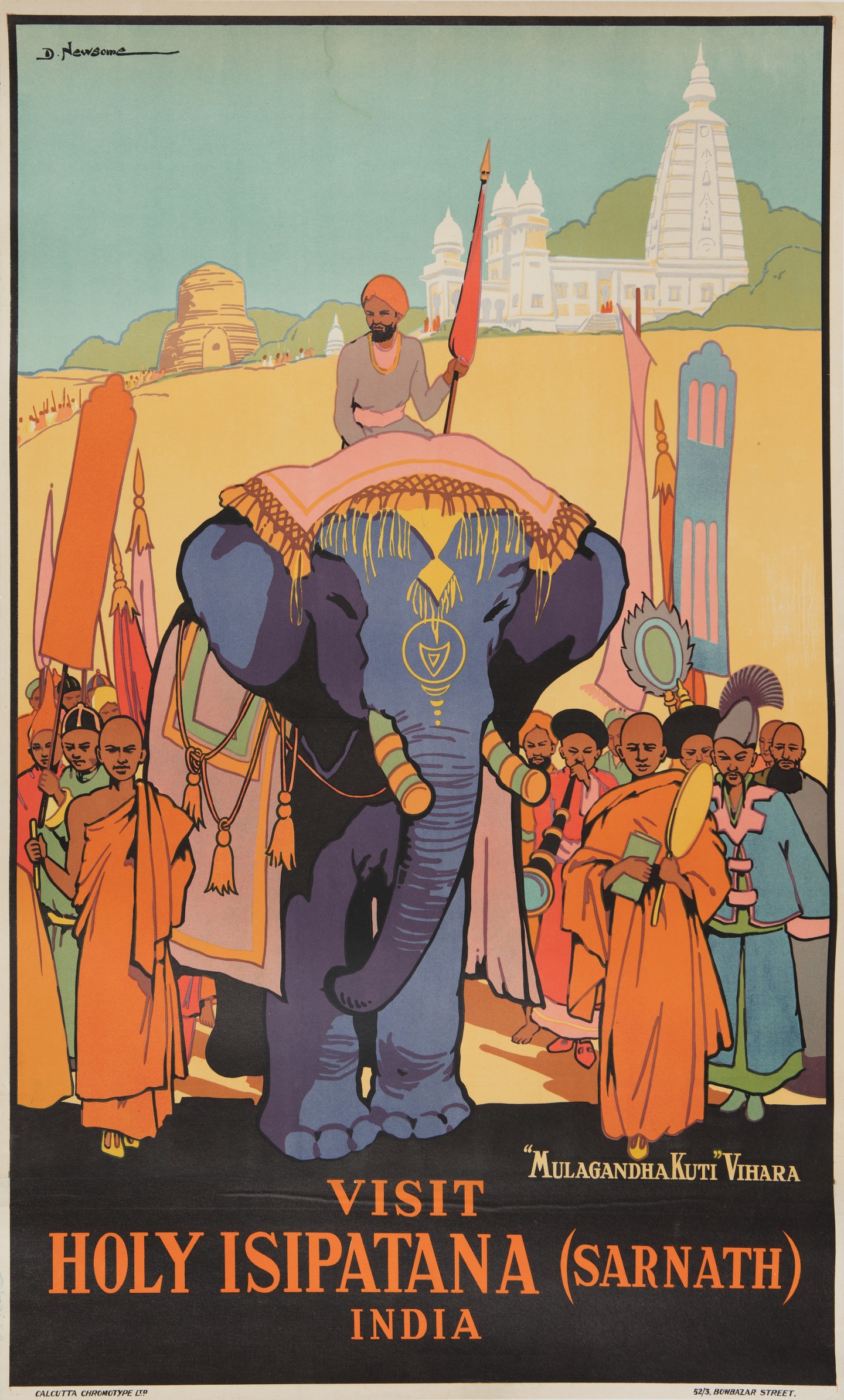

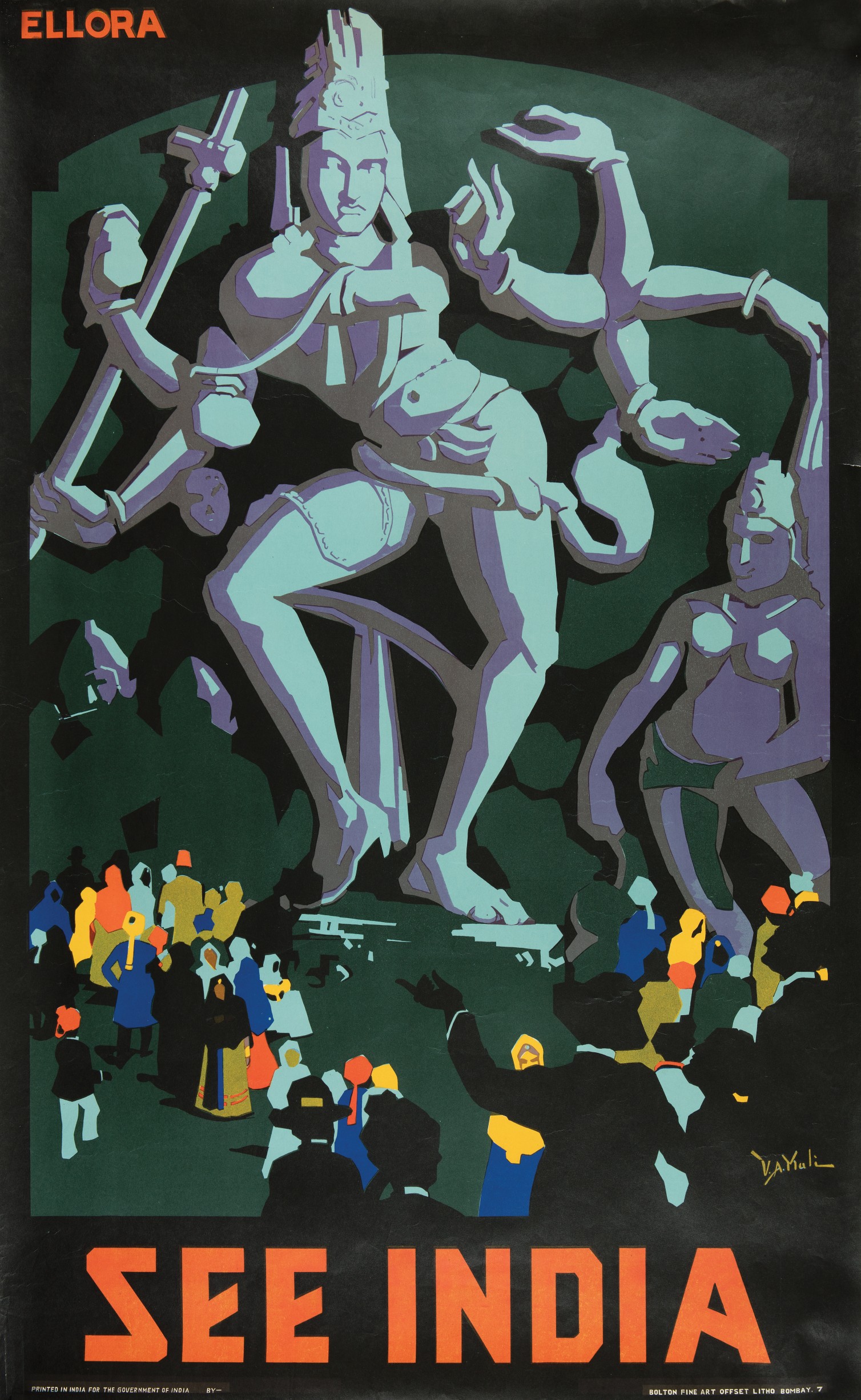

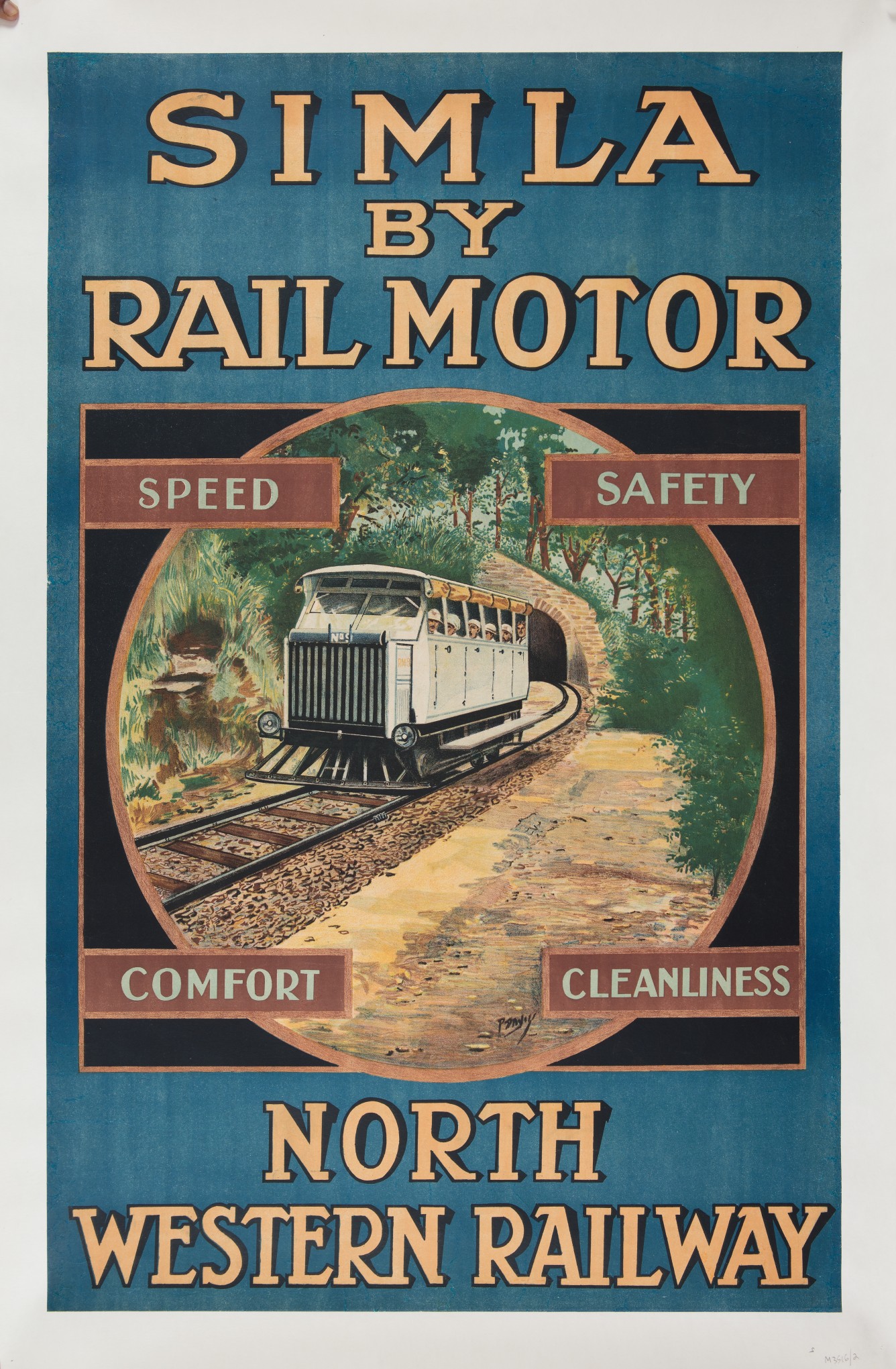

SEE INDIA What picture would you choose for a postcard, to send to a friend who has never been to India? We imagine India variously. For some of us, it is through sounds, smells, and colours. For others, it is about family. 'India' could mean food, textiles, places of pilgrimage, or particular monuments and sites that evoke it. It could be the climate, or the distinct sounds of Indian birds. It could also be through a map, and the familiar places and names on it. How did we get to know the land that is India? One answer is, through travel. People have crisscrossed the subcontinent for centuries, for a variety of reasons. The railways helped to speed things up. Although constructed as an investment with little financial return to India, Indians too used the railways, and in unexpected ways. |

|

Prahlad Anant Dhond Untitled Watercolour on paper |

Dorothy Newsome

Mulagandha Kuti Vihara

V. A. Mali

Ellora

Unidentified artist

Simla by Rail Motor

|

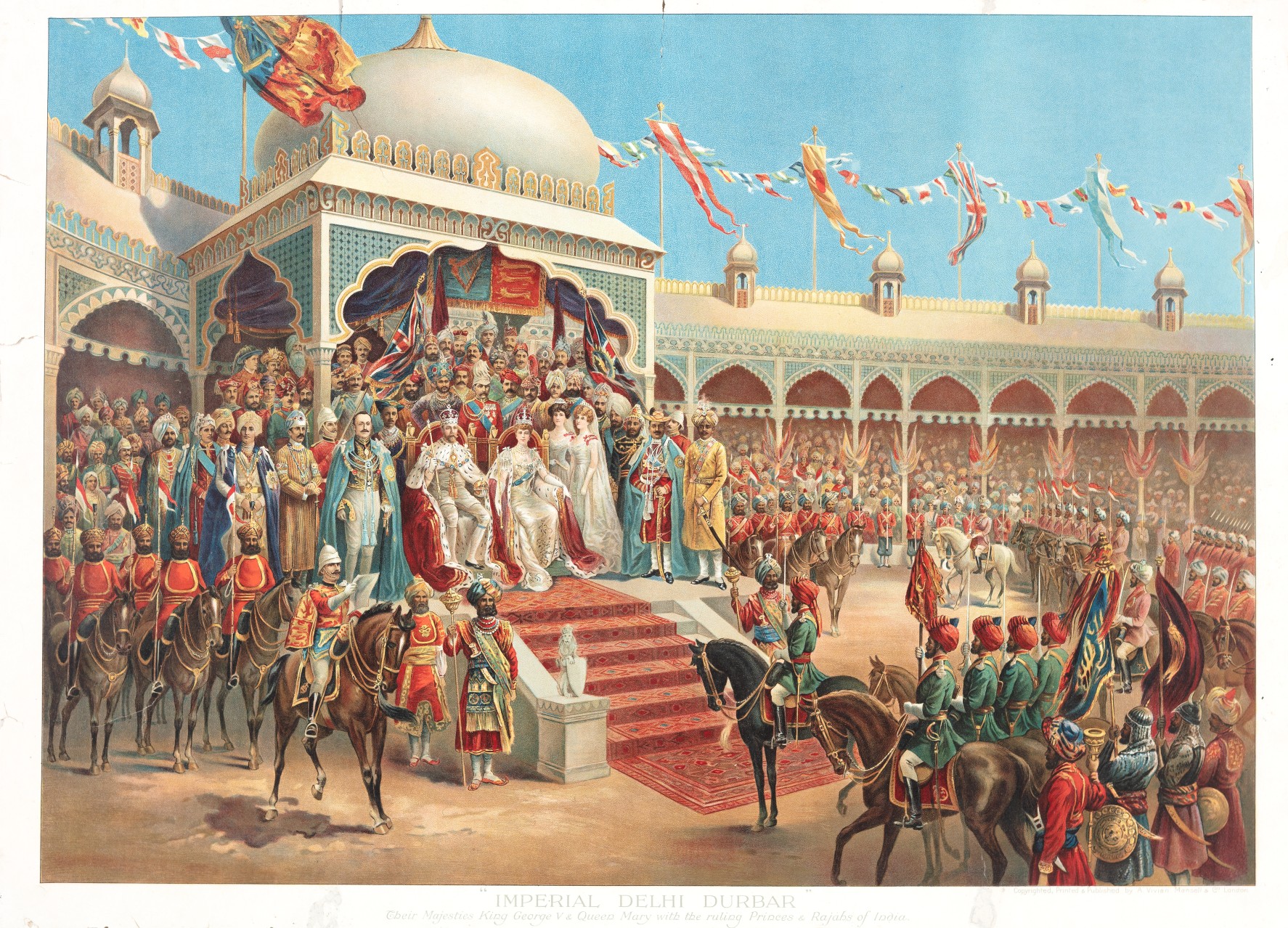

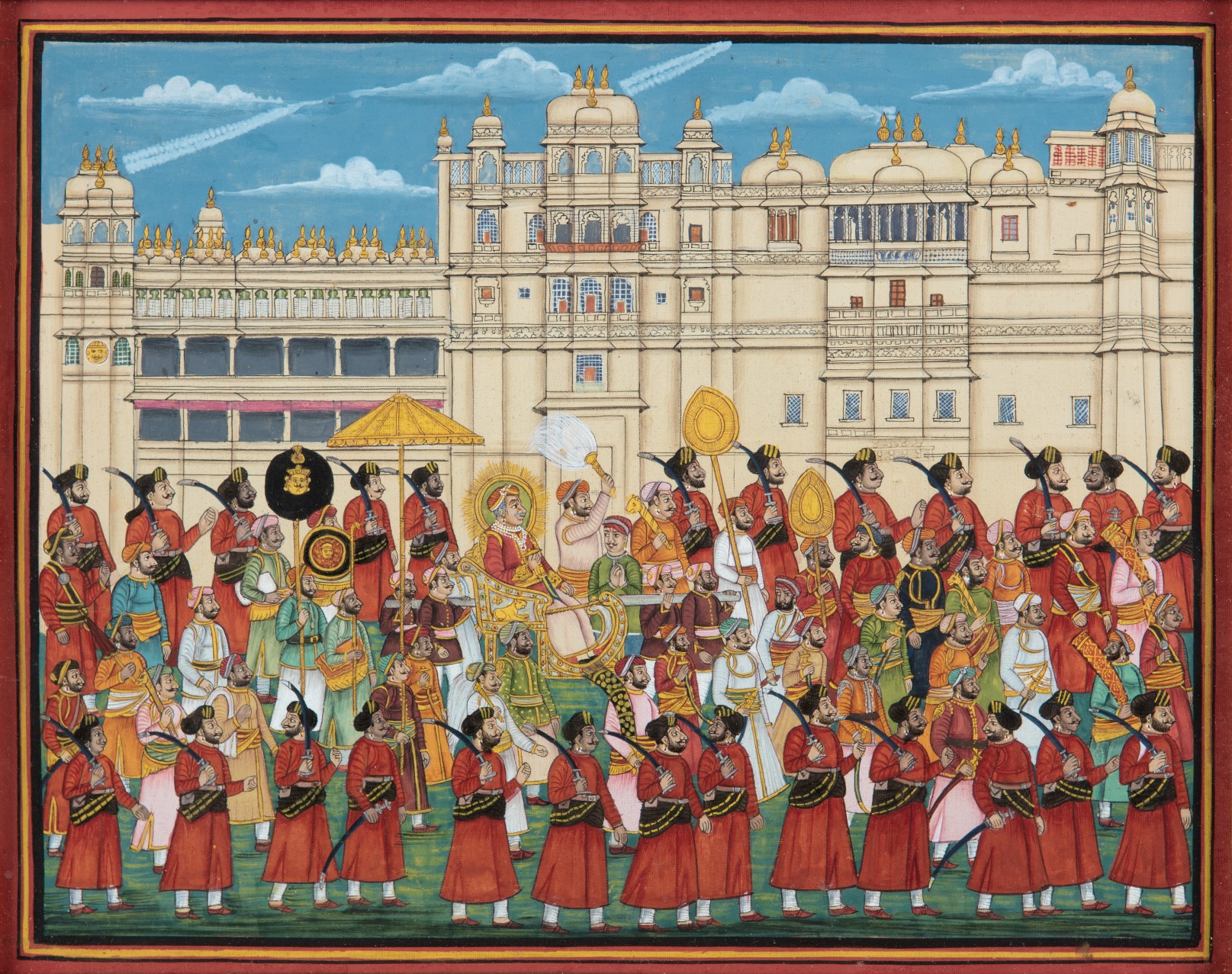

RECLAIMING THE PAST Europeans gained control over the Indian subcontinent, either directly or through treaties with local rulers. Over time, their understanding of India's past shaped our understanding of it. As they began to explore and write about India's history, Europeans used the knowledge they gained to their advantage, for example, by using established practices as processions and durbars to demonstrate their right to rule. Such spectacles, fashioned by rulers to impress their subjects with their power and prestige, were a familiar language to Indians. Europeans simply borrowed it, and used it to communicate their authority as the new rulers of India. |

|

Thomas and William Daniell Jai Singh's Observatory, Delhi Watercolour and graphite on paper pasted on paper |

Unidentified artist

Imperial Delhi Durbar

Unidentified artist

‘The Imperial Durbar’ (The Durbar of 1903)

Unidentified artist

Maharana Bhupal Singh of Udaipur/ Mewar in procession in front of the City Palace

|

EXHIBIT INDIA It is through the arts — whether painting, architecture, literature, music, dance, theatre, or cinema — that human societies best express themselves, and define their identities. In consequence, suggesting the opposite - that people have no art - is also a way of denying their history and identity, and can result in their making every effort to disprove it. Although it was celebrated and sought after in the past, many in the colonial period thought that Indian art had declined, and needed rescue. Distinctions were made between ‘fine’ or ‘classical’ arts such as sculpture, painting, and literature; and ‘technical’, ‘decorative’ or ‘folk’ arts such as metalwork, weaving, and embroidery. These also intersected with gender, class, and caste divisions. |

|

Sunil Madhav Sen Musician Oil, gravel and white cement on Masonite board |

Nemai Ghosh

Shatranj ke Khiladi

Inkjet print on archival paper

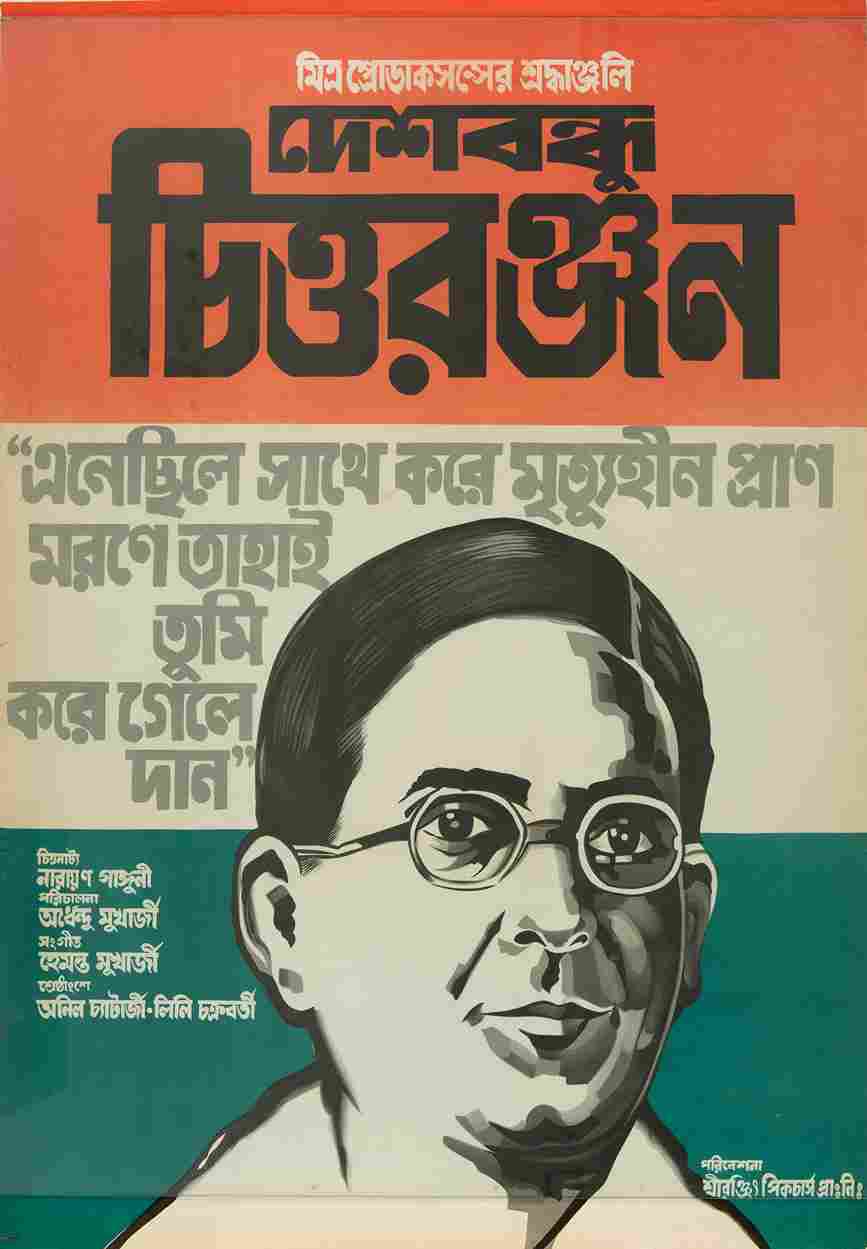

Unidentified artist

'Deshbondhu Chittaranjan' (in Bengali), 1970

Chromolithograph on paper

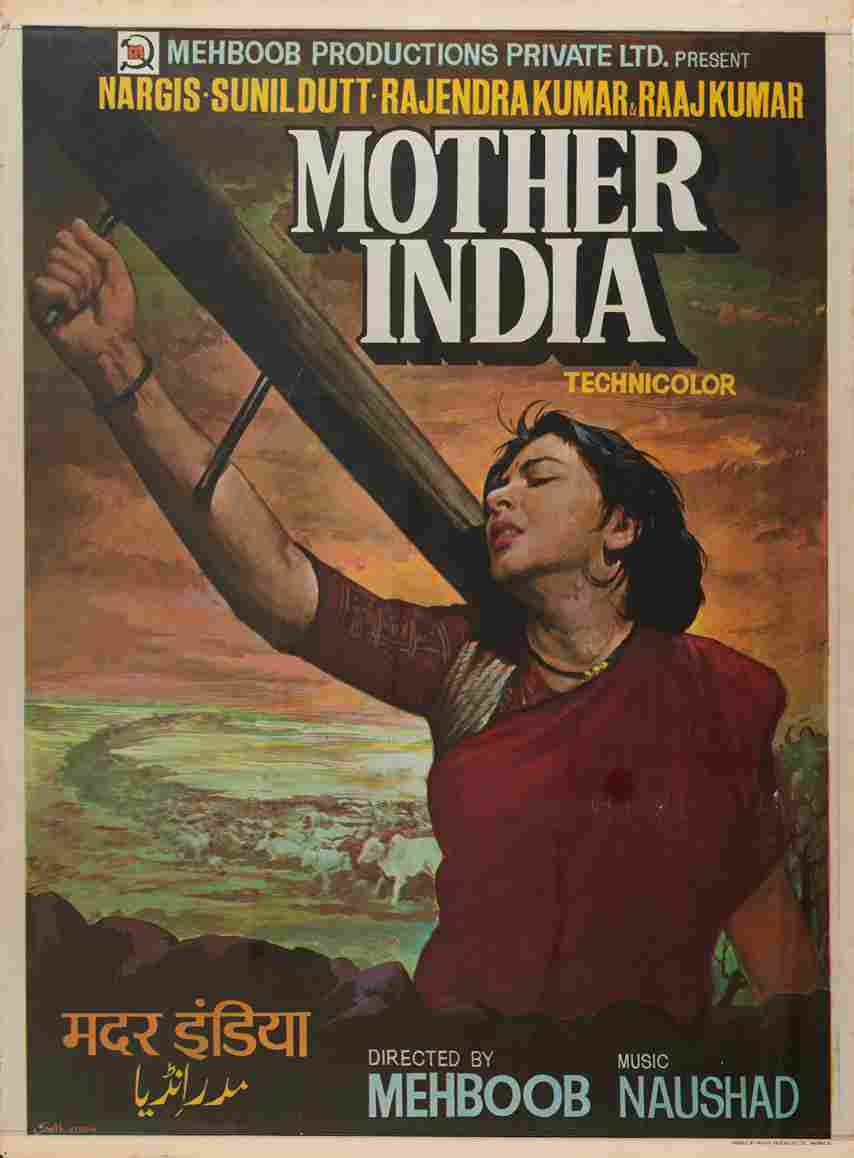

Unidentified artist

Mother India

Offset print on paper

Films are hugely popular in India and have been shown in the subcontinent for over a hundred years. The world was more connected in the past than we realise today. New technologies and inventions like film and photography reached India almost as soon as they were developed. Indians took to the possibilities of film, and adapted it to local subjects and themes. Mythological stories were a popular choice because most of the audience knew the plots, which mattered because films were silent in the early years. They also drew on India’s long history of travelling performers and musicians. Today, of course, film songs are almost more famous than the main story! Another popular theme was the freeodm struggle, or the lives of well known or popular freedom fighters. Bhagat Singh alone has had 7 films made on his life so far. |

Chittaprosad

Lezim

Nemai Ghosh

Bala

|

FROM COLONIAL TO NATIONAL Governing a country spread across a subcontinent is a challenge that rulers and governments of India have addressed in different ways. There are usually some common factors, like buildings and infrastructure, or systems of administration. In the 19th and 20th centuries, the courts, jails, and secretariats from which India was administered were not only places of oppression, but sites of challenge and dissent. They were spaces where 'the public' came together, and learned to particiapte in governnance long before we became a republic. Some sites, like the Red Fort of Shahjahanabad, were older Indian spaces that became 'colonial,' and then 'national.' In 1947, when the British moved out of the barracks built after 1857, the Indian Army moved in until it vacated the premises in 2003. |

|

Dattatraya Apte 'Lal-Qila (Red Fort)' Intaglio on paper |

Prokash Karmakar

Oh Calcutta/ Writers' Building

Oil and acrylic on canvas

Bijan Choudhary

Protest in front of Writer's Building

Watercolour and charcoal on paper

James Fraser

A view of the Writers Buildings, from the Monument at the West End

Engraving, tinted with watercolour on paper

Writers' Building and the square in front of it, have been a stage for the events of our history for nearly 250 years. Originally built to house the ‘writers’ or clerks of the East India Company, the building has undergone changes in both appearance and meaning over the centuries. Writers' Building and the square in front of it, have been a stage for the events of our history for nearly 250 years. The building has changed too. The original plain facade received a grand facelift when it became the Secretariat for the Bengal Presidency. In between, it also served as a college. After independence, it became the seat of the West Bengal government, and was further expanded to accommodate the many new departments that became necessary over time. These three images depict very different imaginations of this significant colonial monument and its presence in our cultural memory. |

A. S. Tendulkar

Institute of Science (and now also National Gallery of Modern Art, Mumbai)

John Gantz

Madras beach and Custom House

|

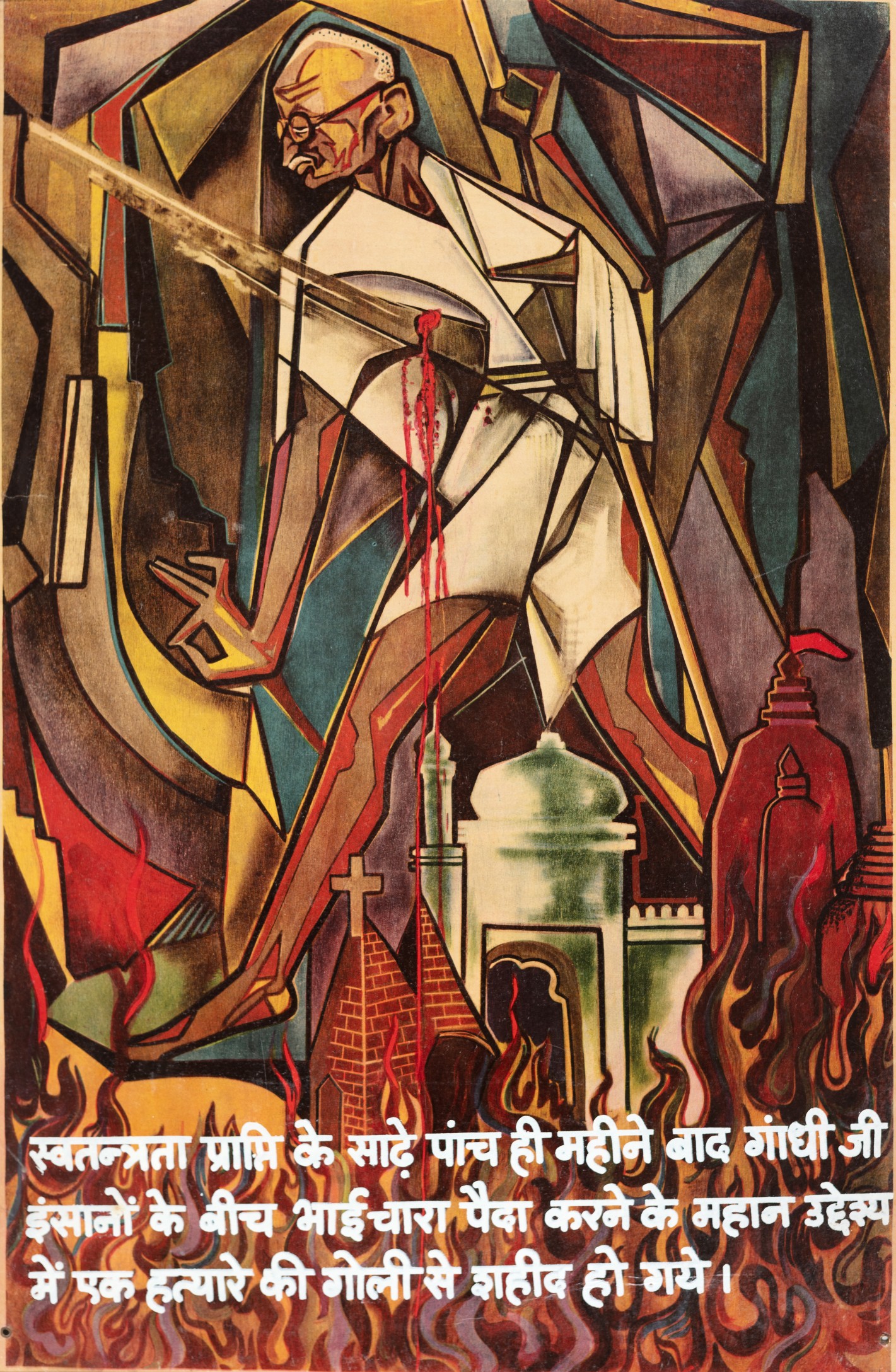

SHAPING THE NATION Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi stands tall as the father of the nation. We are all familiar with his role in our struggle for freedom, and his non-violent methods of protest that eventually forced the British to 'quit India.' But there were in fact many others who worked towards Independence, some of whose portraits are shown here. To succeed, the march to freedom needed people from all sections of our society to take part, and it included both men and women. The people portrayed here had very different ideas on what India meant; what freedom and independence could, and should look like. Their views were shaped by their backgrounds and experiences, as much as the world around them, the individuals they met, and the events they lived through. |

|

Unidentified artist Gandhi poster Offset print and serigraph on paper |

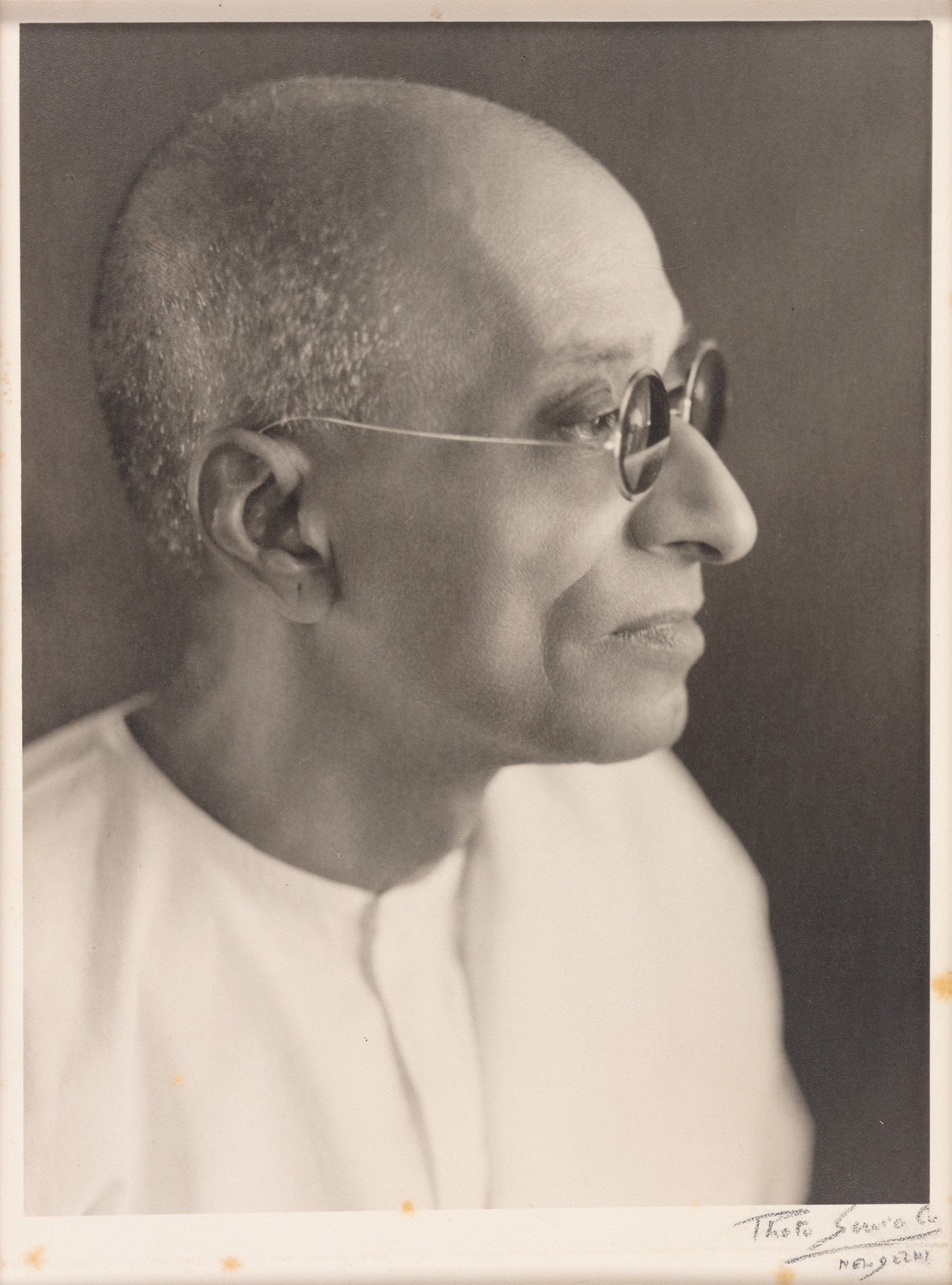

Unidentified photographer

C. Rajagopalachari

Silver gelatin print on paper

V. B. Pathare

Dr Ambedkar

Oil on canvas

Unidentified artist

Gandhi poster

Offset print on serigraph paper

The people portrayed here had very different ideas on what India meant; what freedom and independence could, and should look like. He appears modest and unassuming, but Bhimrao Ramji Ambedkar made formidable achievements in different fields: economics, social reform, politics, and law. He was the architect of the Indian Constitution, a Dalit icon, and known as ‘Baba Saheb’. Ambedkar dreamed of an India in which all its citizens were equal. He worked for it too, through the constitution and through campaigns like the Mahad or Water Satyagraha of 1927, to allow Dalits to use water from public tanks. C. Rajagopalachari, or ‘Rajaji’ was the first Indian to be Governor General of India, and the last person to hold that post, while India was a Dominion (in the gap between Independence and becoming a Republic). He was also a noted writer. The Dandi March was not the only one to challenge the salt tax laws. Have you heard of the Vedaranyam March? Rajaji led the march in what was then Madras Presidency, about a month after Gandhiji’s March at Dandi in 1931. |

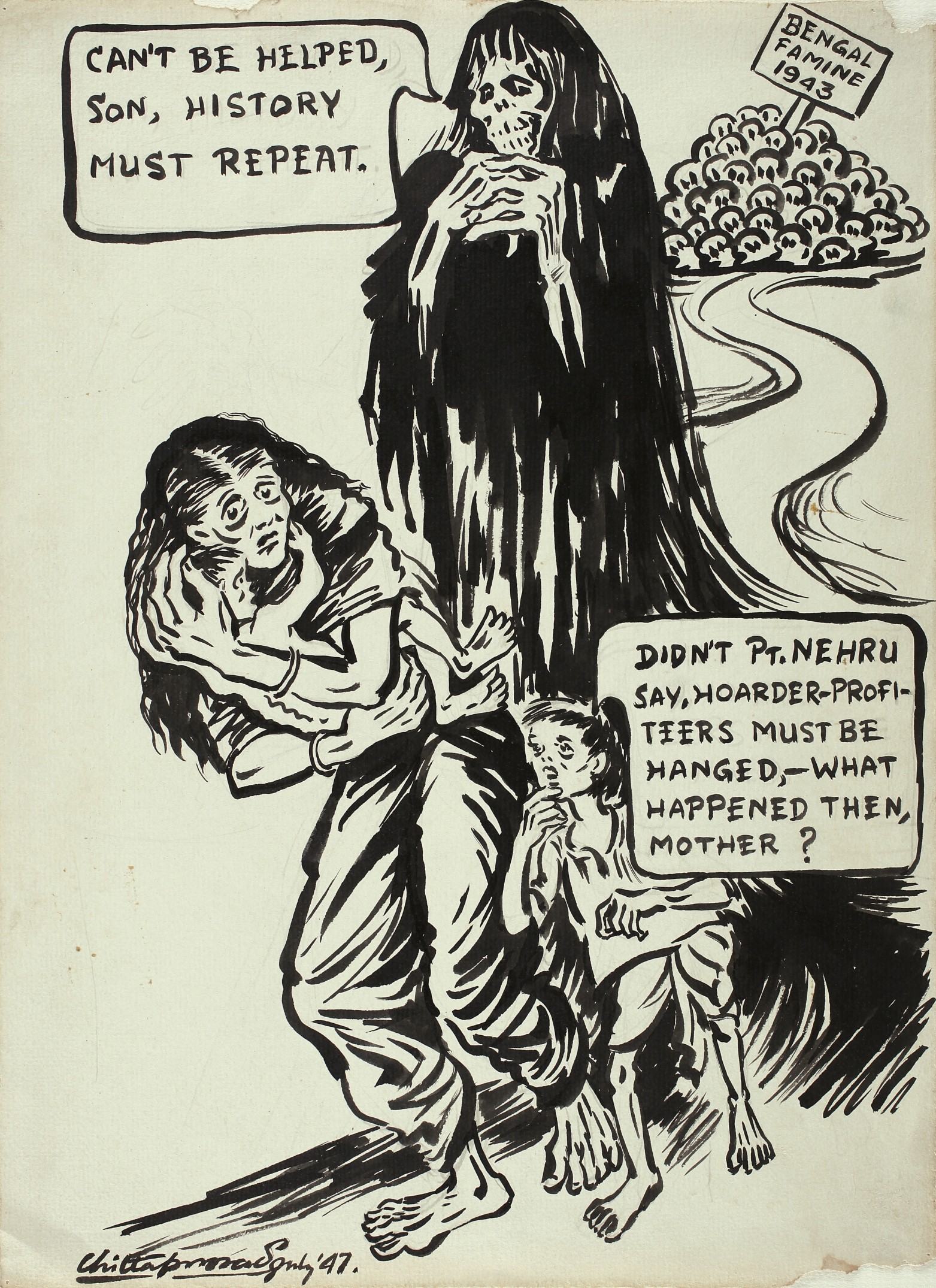

Chittaprosad

Untitled

Chittaprosad

Hindustan, Pakistan, Princestan

These stark and witty drawings offer sharp criticism of politics, politicians, and our society. They were made between 1946 and 1947, in the months leading up to Independence, and after it. They are unsparing, of both Indians and the British. Two of them relate directly to political events — the many plans, negotiations, and committees through which our future was ‘cooked up’, and the options for independence as ‘Hindustan, Pakistan, Princestan’ (that is, a confederation of princely states) that were considered. Everyone in them appears selfish and self-satisfied, focussed on themselves, and their political projects. Chittaprosad, the artist, used the power of his art to comment on the difficult, often miserable, lives of poor people, like in the other two drawings here. His work was banned and burned by the British government for revealing the suffering of ordinary Indians.

|

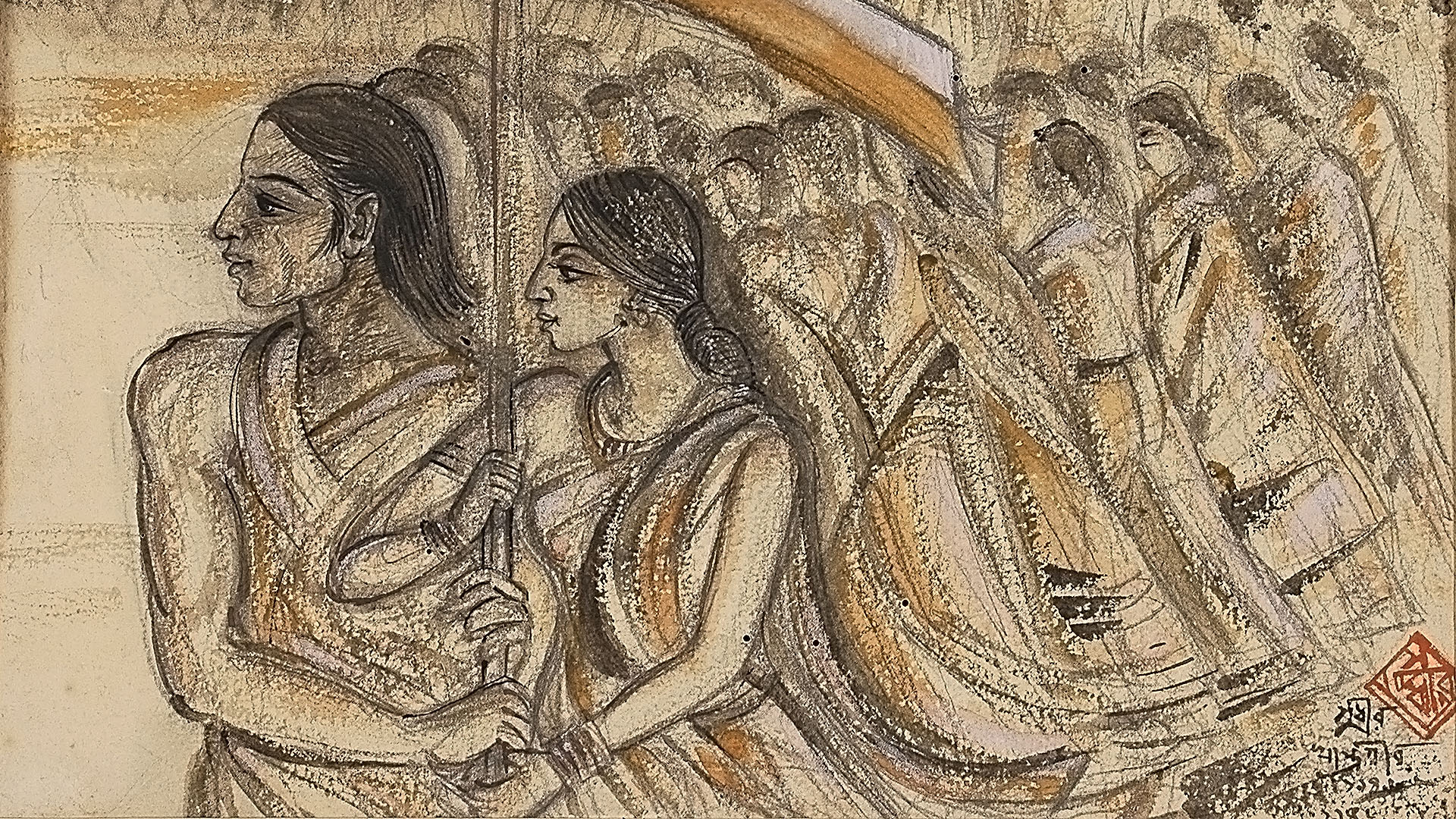

INDEPENDENCE For the crowds gathered to see the national flag hoisted for the first time in an independent nation, it was a moment of celebration that had been long awaited. 15 August 1947 brought a freedom they had fought and sacrificed for. In the east and west of India, religious tensions had required former British provinces in Punjab, Assam, and Bengal to be partitioned. For those caught on the 'wrong' side of the new borders between India and Pakistan, Independence meant being uprooted from the lands they called home, either by choice or force, to migrate, and find a new life in their 'chosen' country. Many did not survive the violence that scarred their journeys, and tainted this moment. |

|

Sudhir Khastgir Untitled Watercolour and graphite on paper |

Satish Sinha

A Refugee Camp in South Calcutta

Watercolour and ink on paper laid on cardboard

Gopal Ghose

Untitled

Gouache on paper pasted on mount board

We often hear stories of people wanting to take refuge in India, because their home countries are being destroyed by war, or they are in some personal danger. India and Pakistan’s independence created refugees within our own countries. We have heard of the thousands who fled in both directions across the new border in divided Punjab. Both partition and the movement of people had a different story in Bengal and Assam. The two governments tried to encourage people to stay (unlike in Punjab, where they tried to help them move).But people moved anyway — just as they did in 2020 during the covid pandemic, regardless of ‘official’ orders or policies. Some were scared, or threatened by hostile neighbours. Others felt strongly about belonging to one particular country rather than the other. |

Henri Cartier-Bresson

Crowds gather in front of Gandhi's room in Birla House

Henri Cartier-Bresson

Soldiers among the crowds gathering at Birla House after Gandhi's assassination

Henri Cartier-Bresson

Gandhi's cremation on the banks of the Jumna River

|

'For many, history is a timeline of events marked by several crucial milestones. However, this method of looking back usually leads to politics, politicians, and battles overpowering other crucial aspects. The exhibition breaks this chronological path to allow the story of India’s freedom struggle to unfold across eight themes.' '‘March to Freedom’: Exhibition re-interprets India’s freedom movement ‘beyond politics, politicians and battles’', The Indian Express, 2 September 2022 'At the exhibition, one of the several taking place in Kolkata to mark 75 years of India’s Independence, the organisers placed a bundle of postcards and a handful of pens on a large table and asked visitors to write down their family memories of that defining moment in history. What has emerged is a still-growing collection of heart-warming as well as heart-wrenching stories that may not be found in history books but which are still a valuable part of history.' 'Postcards bear witness to memories of a fateful 1947 day' The Hindu, 18 August 2022 |

Presented by