|

DAG Recommends Lines of Flight: South Asian Modernists and the art of drawingAnkan Kazi August 01, 2023 The mark of a line binds together our formal understanding of drawing, writing and calligraphy. How can one define the changes taking place in the art of drawing by modernist artists? According to a scholar, ‘a drawing may be distinguished from a painting, or other visual array, by medium or by technique, which in turn depends on who or what institutional agent is classifying the particular work—whether artists themselves or museologists, including paper conservators’. Aside from its objective explanation, as it appears in the eyes of institutions of art, artists have personally responded by making the act of drawing akin to publicizing a set of private inclinations, tendencies and experiments. |

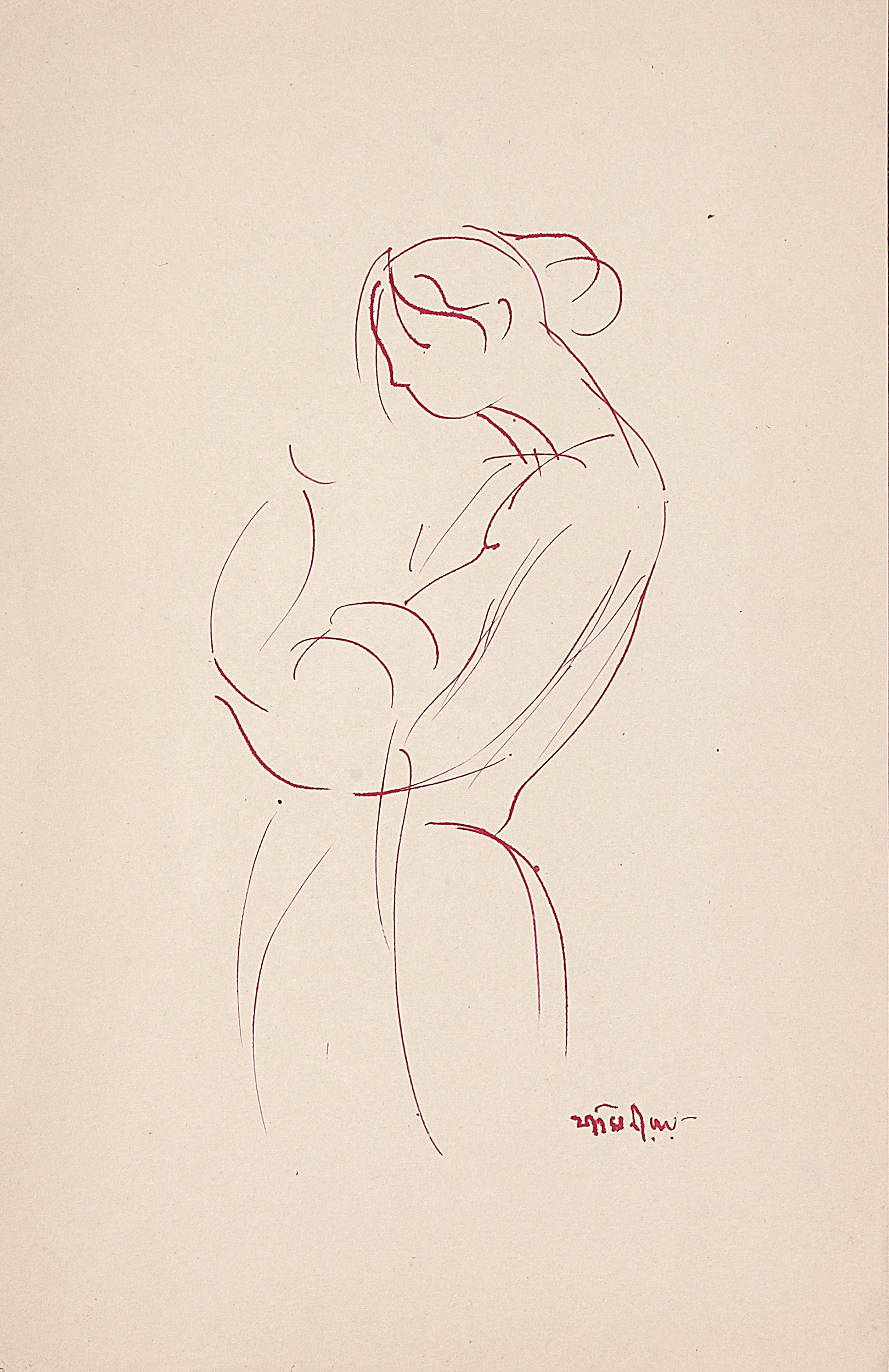

Jamini Roy

Untitled

Collection: DAG

|

Drawing here also expresses a changing relationship with time. Artists were increasingly getting out of the studio to depict realistic scenes and sketches were being appropriated from their colonial role as a tool for measuring spaces and people into one of critical documentation, investing it with the powers of witnessing tragic acts observed on the go, or granting it the ability to suggest expanded freedoms in the realm of sex and morality. However, modernist practices have a long prehistory of inspiration and exchange, especially when it comes to such a foundational act for artists, like drawing. Before rounding up some of our favourite South Asian practitioners of modern drawing, take a look at a surprising story of trade and exchange that can also be told through the global art of drawing, going back to our pre-colonial past. |

|

|

Rembrandt

Two Mughal noblemen (Shah Jahan and Dara Shikoh)

1656

Image courtesy: Wikimedia Commons

Rembrandt

An Indian Lady, after a Mughal Miniature

Brown ink, 3.1 x 2.8 in., 1656-1661

Image courtesy: Wikimedia Commons

Rembrandt

The Emperor Akbar and Jahangir in Apotheosis

pen and brown ink, brown wash and white gouache on washi, 8.3 x 6.8 in., 1656

Image courtesy: Wikimedia Commons

Rembrandt

Woman Wearing Indian (?) dress

pen and bistre, wash, son´me white body color, 7.8 x 5.5 in.

Image courtesy: Wikimedia Commons

Rembrandt: The line of exchangeThe renowned Dutch artist Rembrandt van Rijn (1606—1669) made a series of twenty-five drawings in the 1650s that were inspired by his encounter with Mughal miniature painting. They depicted Mughal emperors, noblemen, courtiers, and sometimes women and common people. Executed on Asian or Japanese (‘Oriental’) paper, Rembrandt's drawings tended to be pared down experiments with figuration and space, focusing more on the Indian subjects’ ‘exotic’ facial features and attire. He used light brown and grey washes, including chalk-marks, on some of these works, and also introduced perspective and shading, elements not typically found in Mughal miniatures. According to some scholars, Rembrandt used the Mughal paintings to study costumes and gestures, but these works may have exerted some influence on the pen and wash style of his late drawings as well. Rembrandt's drawings inspired by Mughal portraits prove visually that he had access to imperial paintings, as well as the expensive Asian paper he worked on, due to the result of increased trading activities between the Dutch East India Company (established in 1602) and Mughal India. |

|

‘By 1956, the critic R. P. Blackmur was writing that the modern poet "found himself seeking a private language and has grown proud of it." A similar proud publication of private language characterizes the mid-century artists represented here, and its syntax was that of drawing in reciprocation with painting.’ -John Elderfield, ‘Master Drawings and Modern Drawings: An Introduction to American Drawing in the Mid-Twentieth Century’ |

|

|

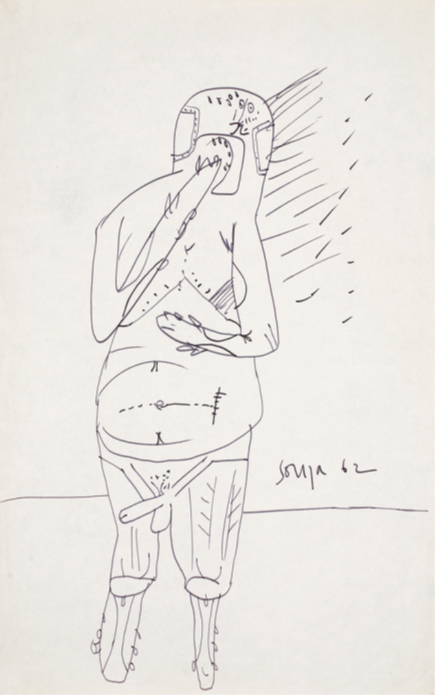

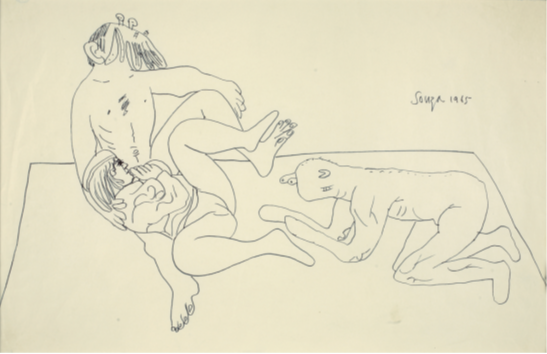

F. N. Souza

Untitled

Collection: DAG

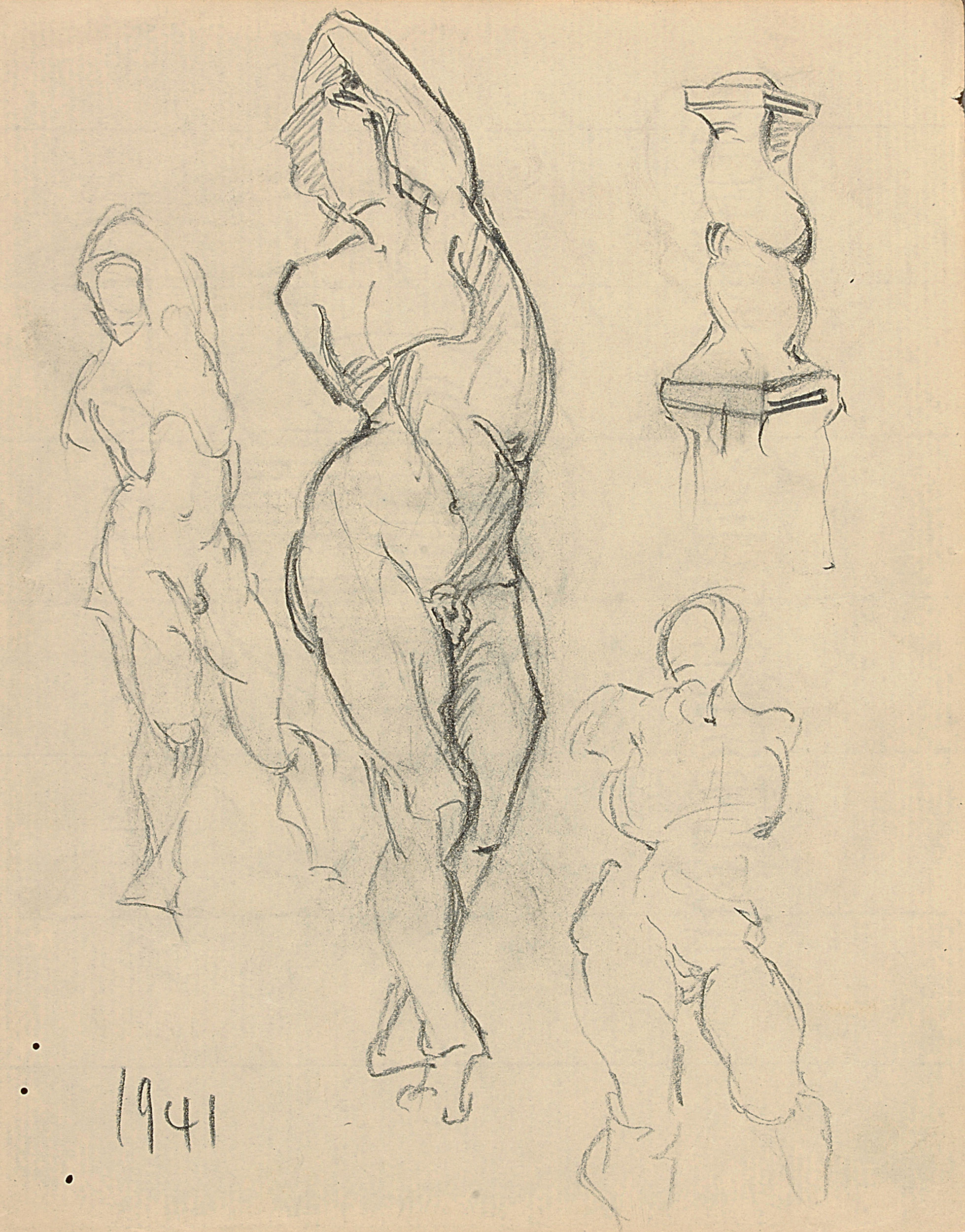

F. N. Souza

Untitled

Collection: DAG

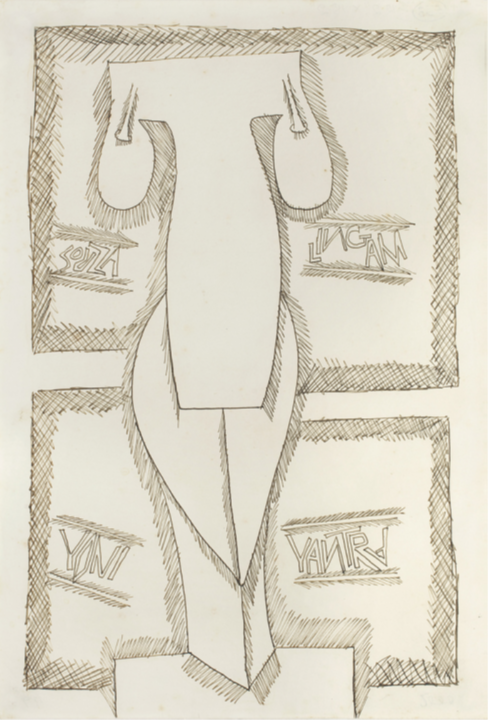

F. N. Souza

Untitled

Collection: DAG

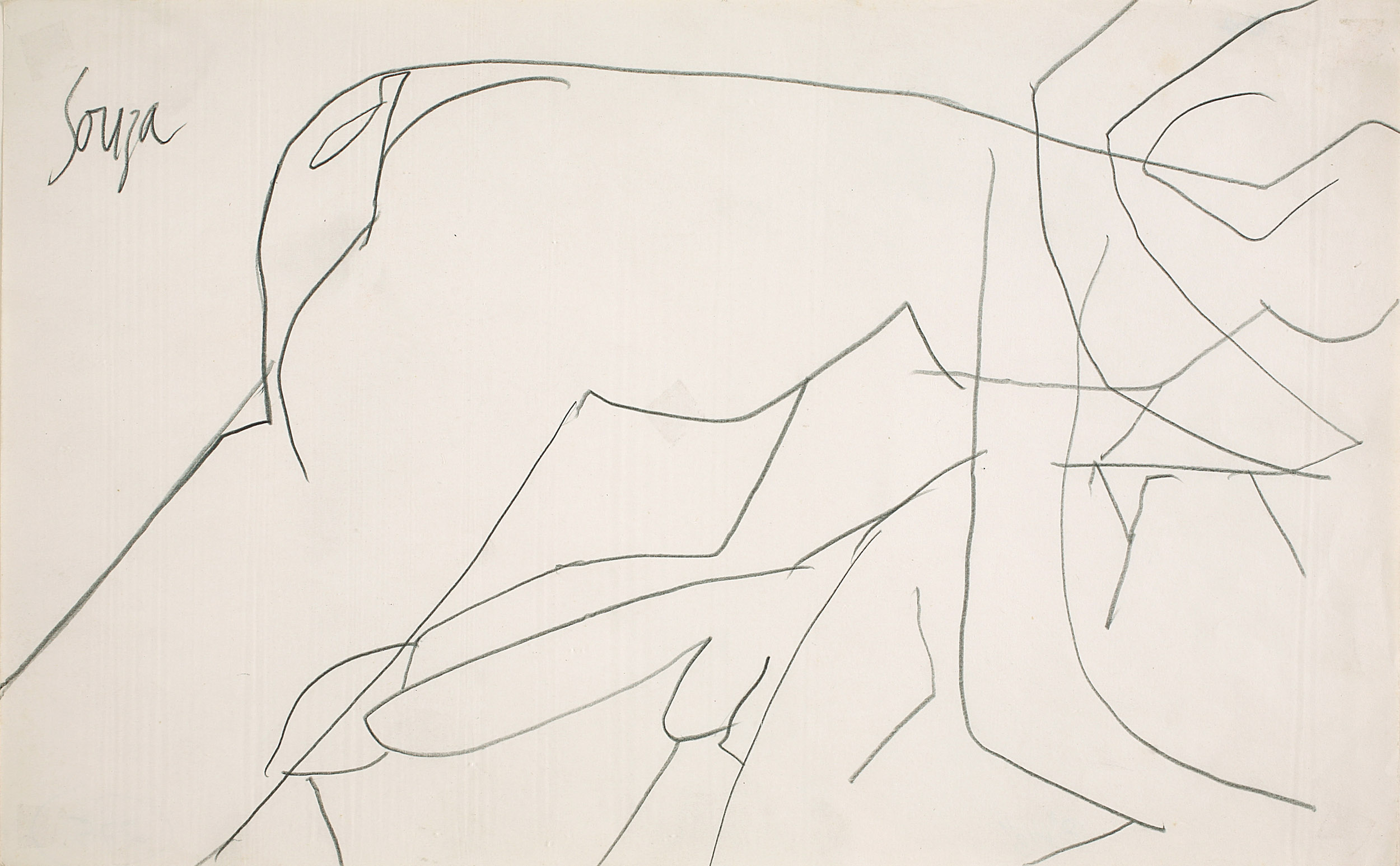

F. N. Souza

Untitled

Collection: DAG

F. N. Souza

Untitled

Collection: DAG

F. N. Souza: The Twisted LineFrancis Newton Souza (1924—2002) was one of the most prominent and controversial Indian artists of the second half of the twentieth century. He was a founding member of the Progressive Artists' Group of Bombay in 1947 but lived mostly in London and New York from the 1950s onwards. Souza experimented with a number of genres and styles, but critics have often singled out his strong figurative practice and line drawings that displayed his mastery over depicting decadent bodies of men and women searching for spiritual grace. Sexual themes, situations and relations were frequently depicted in his drawings, focusing largely on its grotesqueness. His subjects ranged from still lifes, landscapes (sometimes merging into human-scapes), and monstrous nudes to Christian themes such as the Crucifixion, or an emphasis on cephalophoric self-portraits. For him, drawing was a way to employ the tensile strength of the wayward line and it served as the scaffolding on which he built his painted works. Like David Hockney, who has also made several drawings over his career, Souza experimented with innovative drawing tools since his youth, inspired by techniques used by old masters of the Renaissance, such as the camera lucida. He writes in a note from 1962, ‘When I was a kid, I played by projecting a rectangle of light with an oil lamp and a looking glass placed at an angle under the table where it was darkest. I then put small objects before the mirror and traced the projected silhouette on the wall or on sheets of paper. Even today I work in a similar method.’ |

|

|

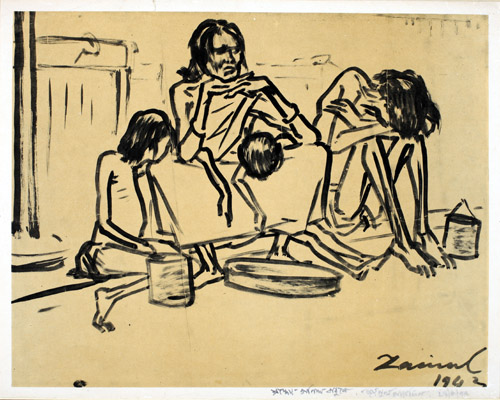

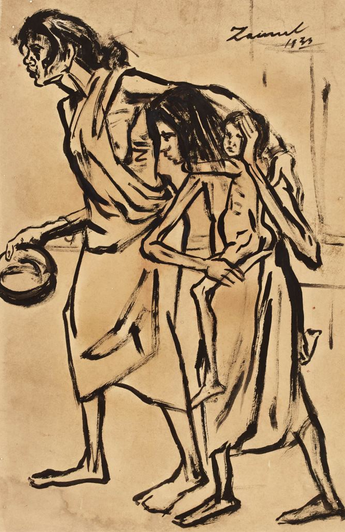

Zainul Abedin

Untitled

Collection: DAG

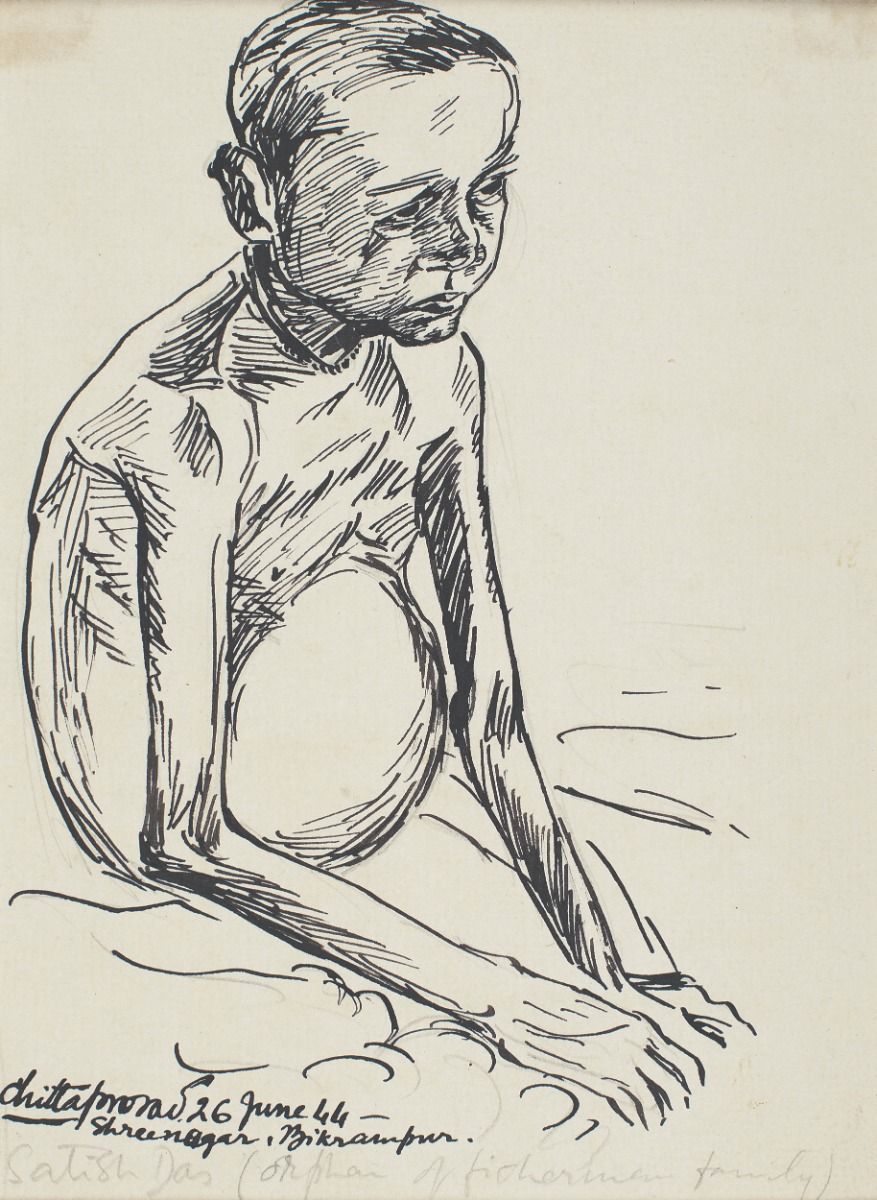

Chittaprosad

Satish Das

Collection: DAG

Zainul Abedin: The line as witnessZainul Abedin (1914—1976) is one of the most influential figures for the development of modern art in East Pakistan, and after 1971, Bangladesh. He received initial training at Kolkata’s Government College of Art and Craft, where he also taught line drawing to students. It was during this time in the 1940s, when the Bengal famine was ravaging the landscape and the national movement for independence was reaching fever pitch, that Abedin made his iconic sketches of the victims of the famine. Along with Chittaprosad and Somnath Hore, Abedin was one of the pioneering artists who centred an art practice around representing the victims of poverty and famine during a time of nationalist triumph, where migrant workers, farmers and labourers were not idealistic or romantic figures for a nationalist elite but the primary bearers of the burdens that were created by war and colonialism. In fact, in some of Chittaprosad’s sketches for the Communist Party of India newspaper, People’s War, he mentions his peasant subjects by name, even writing down details of their tragic stories of displacement or depredation. |

Zainul Abedin

Untitled (Famine sketch)

Image source: Public Domain

Reflecting a time of paucity, when art materials were also hard to come by, Abedin relied on cheap materials for making his sketches; using burnt charcoal for ink or Chinese ink applied to a dry brush, when he wasn’t using a pen, and widely available packing paper or foxed cartridge paper. Through a seemingly minimal arrangement of lines he was able to evoke the fullness of the horror that took place, where the exhausted human body was put into macabre conflicts with crows and dogs to secure scraps of food. Witnessing their sufferings first-hand, Abedin’s work would rescue the idealistic and static image of the Indian subaltern and present their demands as the most pressing one for the new polity that emerged from the ashes of that decade. |

|

|

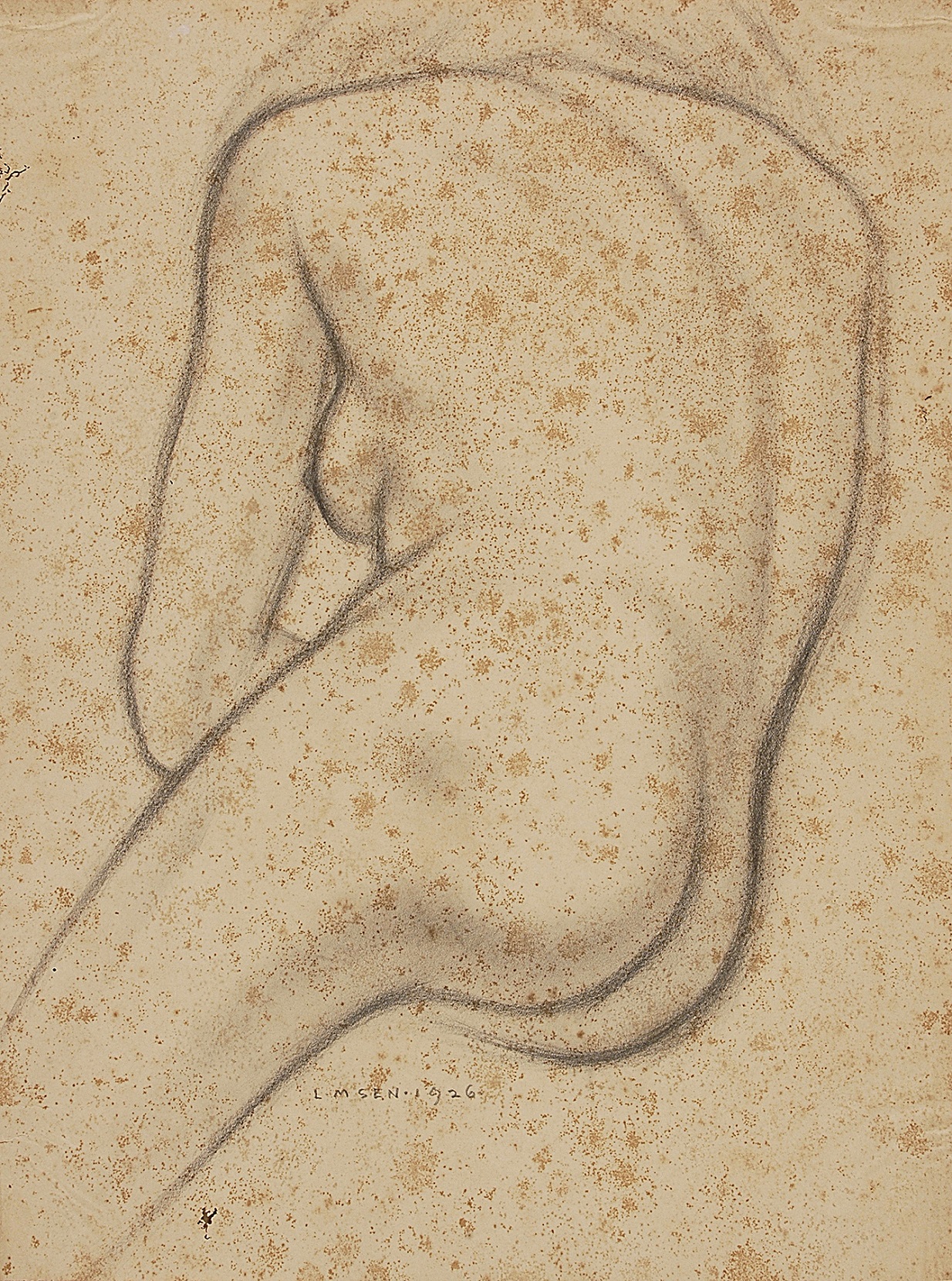

Lalit Mohan Sen

Untitled

Collection: DAG

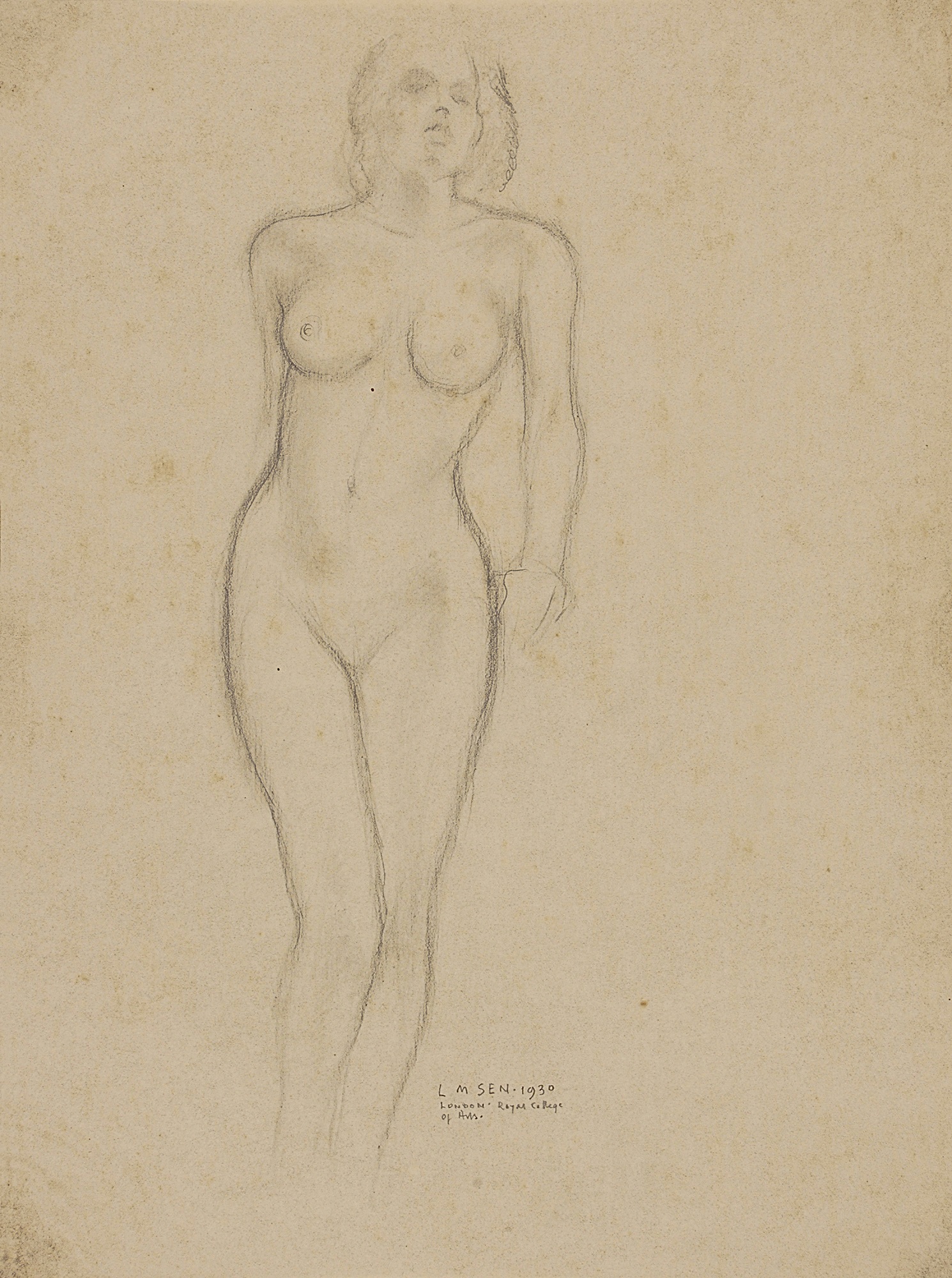

Lalit Mohan Sen

Untitled

Collection: DAG

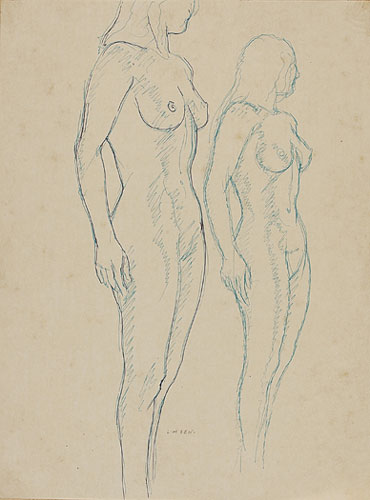

Lalit Mohan Sen

Untitled

Collection: DAG

Lalit Mohan Sen

Untitled

Collection: DAG

Lalit Mohan Sen: The studied lineLalit Mohan Sen (1898-1954) was one of the most successful artists of his time who managed to bridge a career between the west and late-colonial India. He was from Bengal’s Santipur city and was educated at Lucknow’s government School of Art, where Asit K. Haldar taught briefly. Sen imbibed the academic realist art formulated there by British pedagogues like Nathaniel Herd. In his practice, which also included textile design, sculpture and photography—he would express the potentials of both academic realism and modern Indian artists’ search for alternative formal sources from Indian folk and indigenous cultures. Many of his works were centred on representing India’s tribal populations. Aside from woodcuts, linocuts and etchings, he also produced a large corpus of drawings using pencil, pen and ink, and dry pastels. Through these drawings, we are also presented a view into the artist’s pedagogic principles as assimilated from his academic locations. They show various studies of figures drawn for experimenting with poses, gestures, proportions and placement in space in relation to other objects, suggesting their primacy as rough or preparatory work before executing more closely designed tableaux. |

|

|

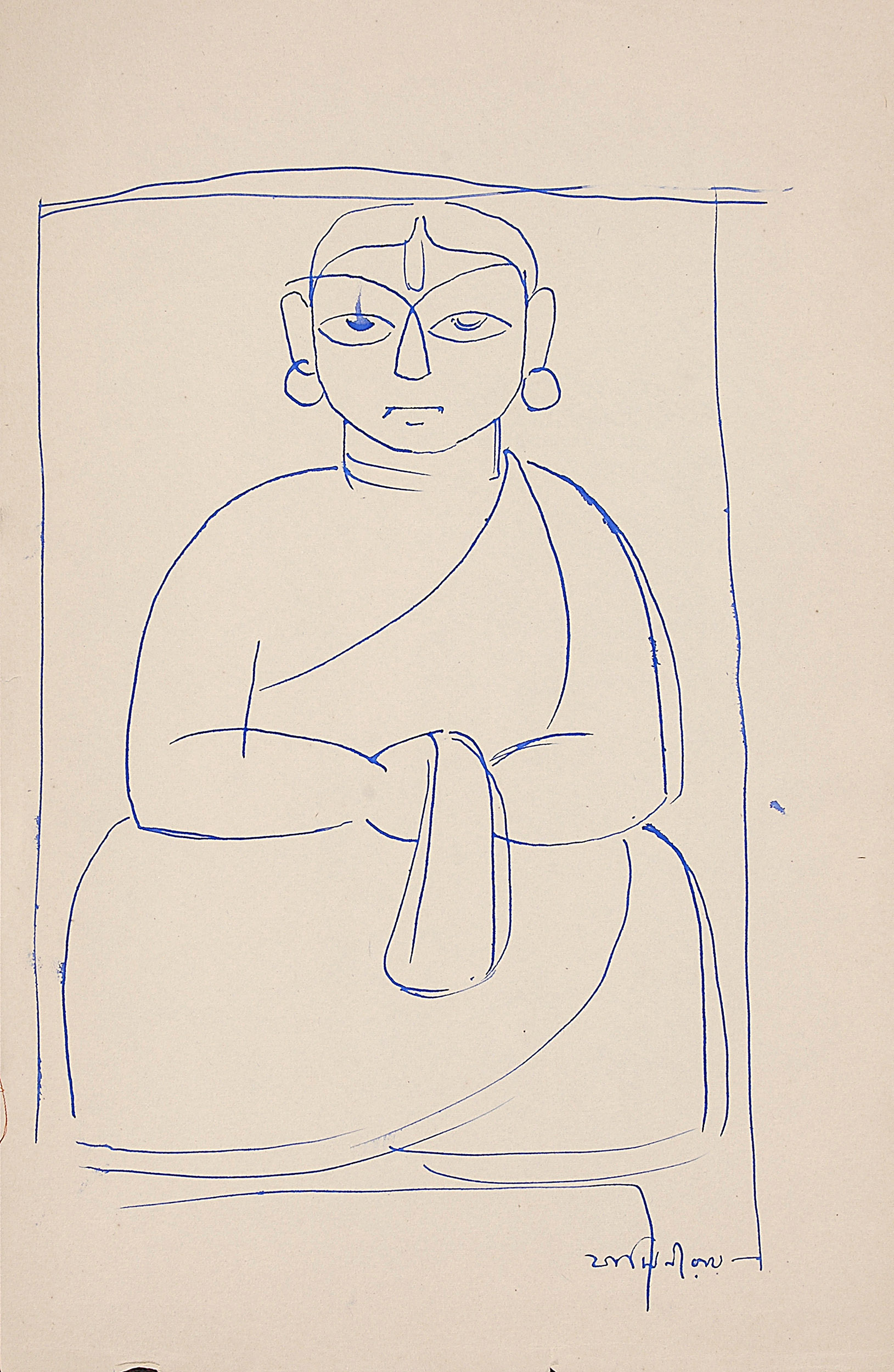

Jamini Roy

Untitled

Collection: DAG

Jamini Roy

Untitled

Collection: DAG

Jamini Roy: The essential lineJamini Roy (1887—1972) is one of the most famous modern artists of India. In 1976 the Archaeological Survey of India (and Ministry of Culture, Govt. of India) declared his works to be considered as ‘art treasures, having regard to their artistic and aesthetic value’ and non-exportable. Roy had forged a career straddling many styles and experiments, eventually settling on his recognizably flat, tempera paintings that drew inspiration from Bengal’s folk cultures and the urban art of the Kalighat pat painters. He made several drawings throughout his career, which is expected due to the high degree of spatial and formal design that went into his work. Borrowing from the language and motifs of temple architecture, his drawings helped him plan the way three-dimensional space could be translated into his flat surfaces. Additionally, Roy arrived at a radical simplicity of form in many of his gouache works which would only employ a singular thick line or two to delineate volume, space and definition of the human bodies he depicted. |

Jamini Roy

Untitled

Collection: DAG

Jamini Roy

Untitled

Collection: DAG

Some critics have argued against the usual motive for looking at Roy’s sketches: as simply plans for his painted works. Pranabranjan Ray writes, ‘Since, unlike in paintings, the lines in the sketches do not have to enclose or define areas occupied by flat colour masses, the lines become free. Unlike the lines in the paintings, the lines in the sketches are not integrally wedded to shapes and motifs, although they by and large define them; hence, we get loose and discontinuous ends of lines in the sketches… As a result of the character of lines, the shapes and agglomerations of shapes (i.e. the motifs) attain a kind of flexibility.’ ’ Due to this achievement of flexibility and movement, Roy’s sketches have often attracted greater praise over his late period paintings that have struck some viewers as too static and closely designed. Nonetheless, Roy’s sketches provide a fascinating case study of the complex relationship between drawing and painting in modern art, and holds proof of the level of experimentation he engaged with even as he employed a deconstructionist’s ethic of removing every inessential line or mark from his ‘final’, painted image. |

|

|