Jamini Roy on Rabindranath Tagore's Art

Jamini Roy on Rabindranath Tagore's Art

Jamini Roy on Rabindranath Tagore's Art

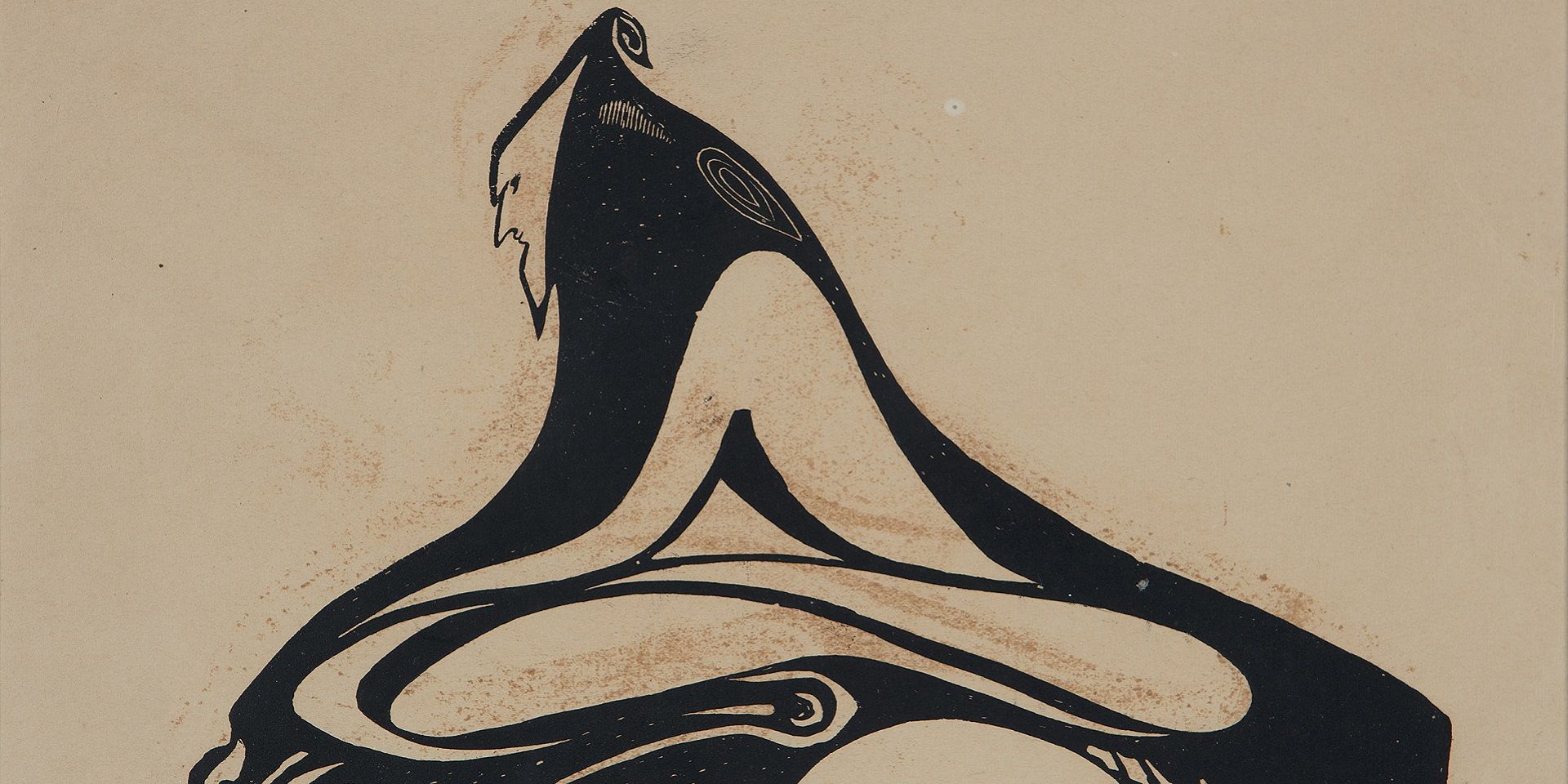

Rabindranath Tagore, Untitled (Namaz) (detail), Woodcut on newsprint paper, Collection: DAG

What was primitivism, and how did it provide an aesthetic lens for modern artists committed to a project of artistic renewal?

‘Primitivism’ was a trend among modern artists that involved looking to the past and to distant cultures for new artistic sources. It played a significant role in the development of modern art, radically changing the direction of European and American painting at the turn of the twentieth century. However, primitivism, as practiced in the west, was also an inherently Eurocentric enterprise and biased against the very arts it tended to appropriate. Giles Tillotson has offered two possible definitions that can help us understand the primitivist impulse in modern art: ‘first, as a tendency to identify with or attend to elements of society that are deemed ’primitive’, and secondly the simplifying of technique and reducing of the formal means of expression to a ‘primitive’ state’. Jamini Roy and Rabindranath Tagore’s works have often been suggested to bear traces of these primitivist impulses that were at play during their working lives. Tagore had travelled widely in the west and had seen many such shows exhibiting works by modern primitivists.

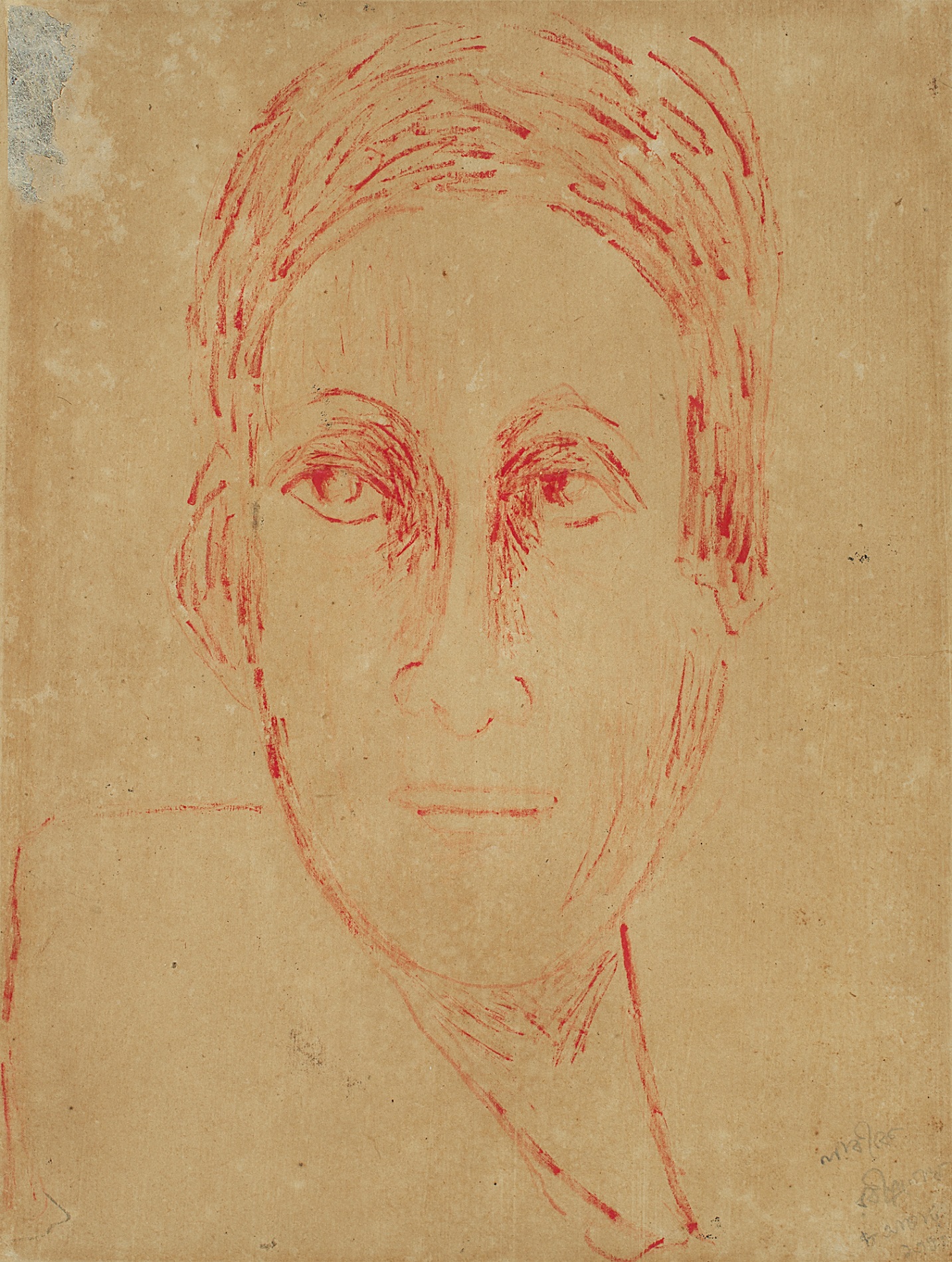

Jamini Roy, Untitled, Tempera on cloth, 36.1 x 63.5 cm. Collection: DAG

Roy, who was much younger than Tagore, and who already looked up to the great man for his many creative achievements, wrote about and corresponded with Tagore on several occasions—exchanging their views on art. In this essay, intriguingly enough, Roy identifies Tagore with the primitivist spirit, finding his inadequate training in art to be a boon to his creative vision, roughly corresponding with Tillotson’s second definition. In the case of Roy, however, it would be difficult to claim that an absence of formal training led to an evolution of his primitivist/ folklorist practice, since it was arrived at after various formal experiments, rigorous training and various other stages of art that he passed through. In this essay, translated and extracted from a longer, original Bengali text titled ‘Rabindranather Chhobi’ (Rabindranath’s Paintings), he writes about Tagore’s art, responding to the significance of his spontaneity, as opposed to the strict regimen of art taught in the influential institutions of the time in colonial India.

Rabindranath’s Paintings

Jamini Roy

Rabindranath paints in an authentic European style. Therefore, to understand his paintings, one must know what the problems and objectives of modern European paintings are. A famous European artist once said about some sculptures made by his contemporaries that if only these works could be thrown off a cliff some life would enter its broken fragments. In other words, European artists are tired of realism and are looking for a new path. They see that art’s purest expression was achieved as early as the primitive ages. At that time there was no need to cover up artistic expression with civilizational ideals and there was no inclination towards reproducing photographically accurate images. The sole intention was to represent—as nakedly as possible—the affect or emotion evoked by the subject matter being depicted. As a result, when we see a prehistoric image drawn on the walls of a cave—perhaps depicting a horse, we understand that it is meant to be a horse; even though it may not have the precise details that can allow one to identify which horse was being drawn. Thus, only the fundamental essence of the horse has been captured. As civilization began to progress, artists began to be inclined towards realism. People began to feel embarrassment at their naked bodies and began searching for ways to cover up or decorate themselves; and the burden of artificiality also began to increase. Similarly, artists too began to feel ashamed of depicting merely naked bodies; refinement of form, embellishment—these were the procedures that began to occupy them henceforth. The embellishments were achieved, but life was snuffed out of these images. The act of construction, of creating structures, was lost. The depredations of civilization were beginning to exhaust art. This is why today’s artists have begun to journey against the tide of realism. Let the embellishment be and resurrect life instead—this seems to be their motto.

|

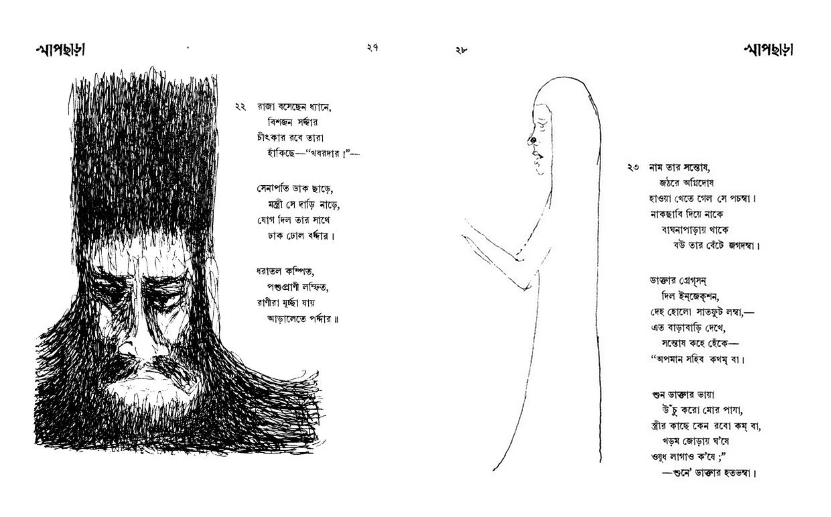

Rabindranath Tagore, Untitled, Pastel on paper, 26.7 x 19.6 cm., 1910. Collection: DAG |

A strange thing seems to have happened around Rabindranath’s paintings. He does not have any experience of the middle-stages of a progressive art practice, or the steps that one needs to take to reach a final stage. In this situation, failure is almost inevitable, but surprisingly, in his case, it is not so. Looking at his greatest paintings it is hard to tell that he has only lately arrived at his art practice. I can only find one explanation for how he manages to overcome his lack of experience: his exceptional power at capturing the rhythm of his imagination. The question of line and colour has been resolved by the workings of his powerful imagination; it would be foolish to find faults with his inexperience after this. But then again, his imagination is unable to remain vigilant and powerful all the time, and traces of his lack of experience have been allowed to surface occasionally in those moments. For instance, if one looks at some of the sketches he made for Khapchhara (Out of Place), one will notice that most of it is executed in the same, assured manner, but when it came to marking noses or eyes he has reverted to making realistic strokes. Of course, while discussing any artist one must consider only their best works. And in Rabindranath’s best pictures the forbidding watchman of his powerful imagination has managed to dispel any approach of inexperience.

|

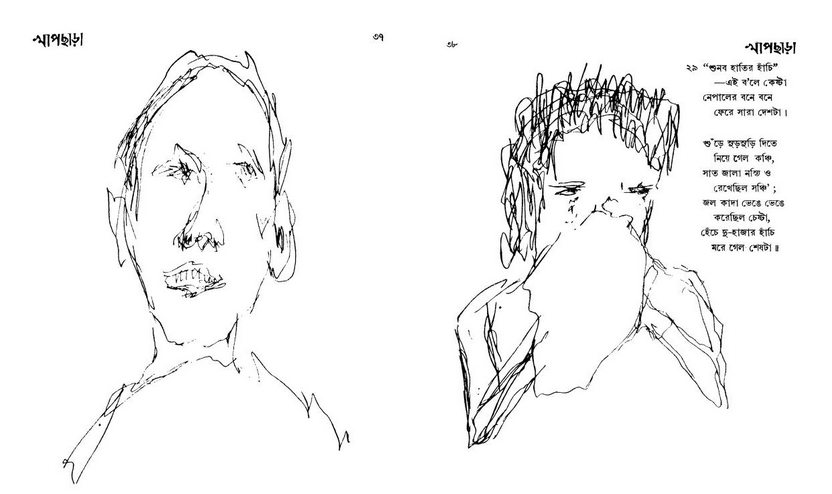

From Rabindranath Tagore's Khapchhara (Out of Place). Image courtesy: Wikimedia Commons |

I admire Rabindranath’s paintings for their power, rhythm, and the indication of a majestic form being apprehended. These days I hear a lot of objections against such images in our country; they say these lack anatomical fidelity. I feel, on the other hand, that these are the only kinds of images that display any kind of awareness of anatomy today. After all, what is the significance of anatomy in image-making? This is a discipline that can inform artists about the body—nothing more. The main purpose of bones in our body is to keep it upright, solid and straight—and not let it stoop. Isn’t this strength most visible in the images we are discussing now? When we see a person’s image painted by Rabindranath it does not look like they are going to fold in on themselves or that they are being buffeted by the wind. We can see, instead, that they have mass and a backbone. Rabindranath’s paintings acquire power due to these bone structures, and the rhythm of their construction. In my opinion, over the last two hundred years, since the time of the Rajputs, a lack was growing steadily in our traditions of picture-making, and Rabindranath stood in opposition to this; he looked for a strong spine for his images.

|

Rabindranath Tagore, Profile of a Woman, Pastel on paper, 31.8 x 10.7 cm., 1936. Collection: DAG |

I am also astonished by the manner in which Rabindranath evokes greatness in his paintings. Let me explain what I mean… Portraits are usually painted while observing the subject directly, which can allow a scientist to tell precisely how far they stood from the artist while they were being painted, where the light was streaming in from, etc. When we paint the face of a subject we tend to observe only the face as closely as possible, not any other part of the body. And when we are painting the lower part of the body then we look closely at that corresponding part in the subject’s body, not the face. We see the same person standing ten feet away in a certain manner, but it changes when they move a hundred or even two hundred feet away. But when that person is completely removed from our view are we still not able to see them? Yes we can, we see them whole; and to paint these visions that are not visible to the naked eye is the special distinction of Indian art. In Rabindranath’s art this distinction shines through. But Rabindranath is a man of our time, so he is not specially endowed with the certainties or convictions of a classical, or Pauranic age. It is the playfulness of his personal imagination that allows him to reach this level of distinction in his art.

Translated by Ankan Kazi

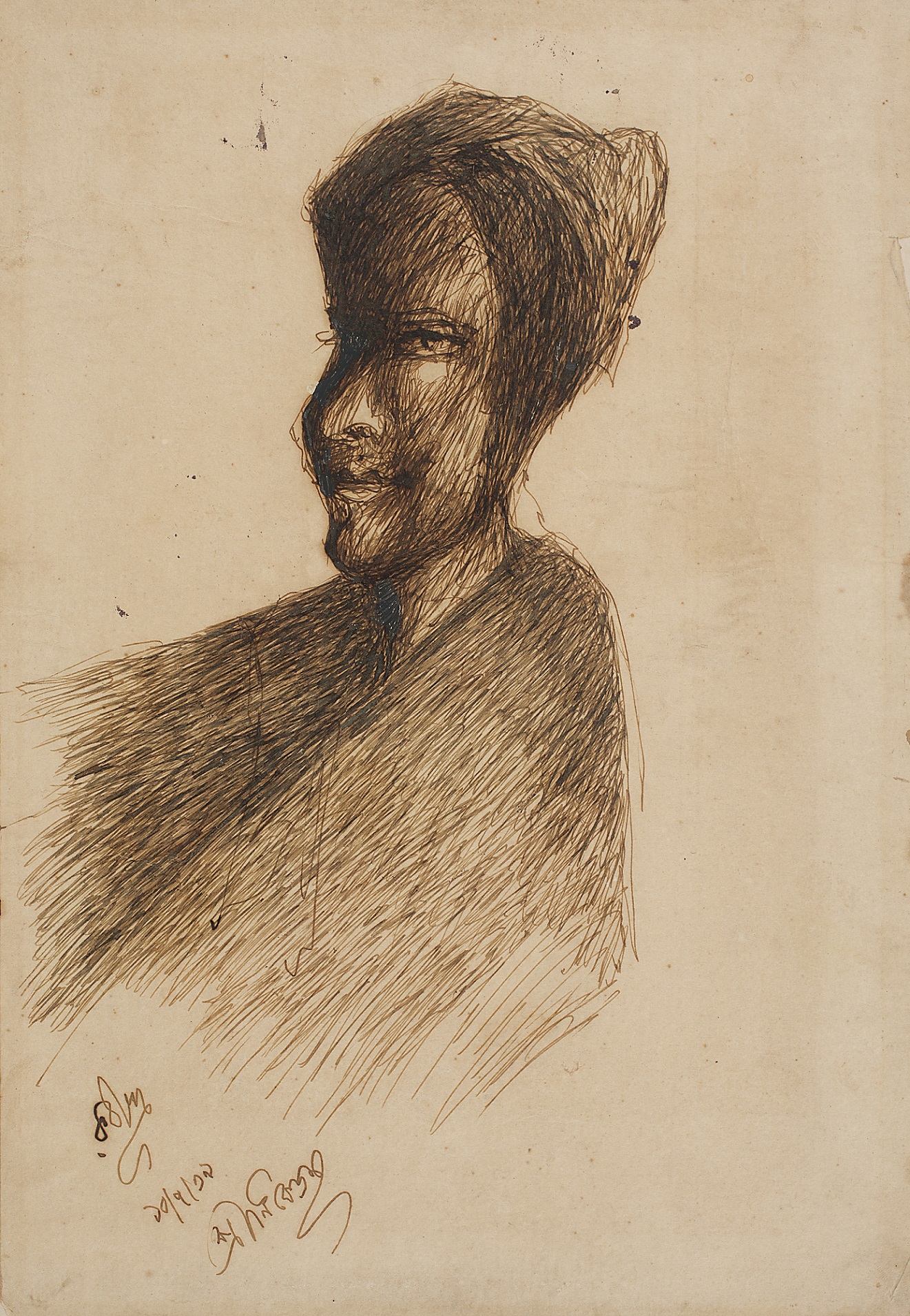

Rabindranath Tagore, Untitled (Head), Ink on paper, 39.4 x 26.7 cm., 1939. Collection: DAG