Imaginary Neighbourhoods: The Worlds of Tyeb Mehta and M. F. HusainAnkan Kazi April 01, 2025 A brace of events concluded our festival, ‘The City as a Museum, Mumbai’, confronting the rich histories of old neighbourhoods in the extended areas around Sir J. J. School of Art that have contributed artists, imagery and a mixed heritage of building and co-existence that has shaped the ethos of the city. Led by the cultural anthropologist and historian of architecture Sarover Zaidi, along with filmmaker Avijit Mukul Kishore, graphic novelist Sarnath Banerjee and Naheed Carrimjee, we gathered at the Mohammedi Manzil building on Mohammed Ali Road to learn about the intricate connections these spaces hold with the larger phenomenon of migrancy and art-making in the city, since the nineteenth century. |

M. F. Husain

Untitled (Horse and Falcon)

1972, Ink with wax on paper, 13.7 x 19.7 in.

Collection: DAG

|

Bhendi Bazaar, established during the colonial era, was initially designed to house migrant workers supporting Mumbai’s port and trade activities. Over time, it evolved into a vibrant cultural hub, home to communities such as Dawoodi Bohras, Memons, and Parsis. |

|

|

Raudat Tahera

Image courtesy: Wikimedia Commons

Chandelier inside the Raudat Tahera

Image courtesy: Wikimedia Commons

The area is renowned for its tightly packed chawls and old buildings featuring tiled roofs, rounded corners, intricate balustrades, and balconies that reflect a blend of colonial and indigenous styles. Notable landmarks include the Mughal Mosque, also known as the Blue Mosque, which showcases Iranian architectural influences with its striking blue tiles, mosaic designs, manicured gardens, and tranquil pond; and the Raudat Tahera mausoleum, an elegant white-marble structure with Quranic inscriptions, which is used by the Bohra community. |

|

|

Mohammed Ali Road complements Bhendi Bazaar's built heritage with its bustling streets lined with historical mosques and markets. The road is a melting pot of cultures and its architecture mirrors the coexistence of communities arriving from West Asia, parts of eastern Africa and the Gulf countries, exhibiting traits of a formative Indian Ocean architectural idiom, with older structures blending seamlessly with contemporary developments. This area is particularly famous for its vibrant street life during Ramadan, when food stalls offer Mughlai delicacies alongside traditional clothing and jewellery markets. |

Mohammedi Manzil overlooking the J. J. Flyover

Sarover Zaidi

We gathered at the Mohammedi Manzil building to host a discussion on the influence of these neighbourhoods on the cultural work of artists such as Tyeb Mehta and M. F. Husain, and share a communal iftar meal. The house overlooks the ‘J. J. flyover’, officially named the Qutb E Konkan Makhdoom Ali Mahimi Flyover, which was constructed in 2002 as a 2.4 km elevated road to ease congestion along Mohammed Ali Road and connect the city’s northern neighbourhoods to South Mumbai. However, as Sarover Zaidi critically observed, its construction embodies more than just urban planning; it reflects deeper socio-political dynamics of segregation and control. |

|

|

Zaidi described the flyover as an assertion of ‘sovereign verticality,’ a concept developed by Eyal Weizman, which highlights how infrastructure projects can impose authority over marginalised communities. The J. J. Flyover runs above what is historically known as the ‘native Muslim town’ of Mumbai, a space shaped by diverse Muslim trading communities. After the 1992-93 riots and subsequent communal tensions, this area became stigmatised as a ‘problem zone’, which media representations—including cinema—also reinforced. The flyover, while solving traffic issues, also bypasses these neighbourhoods, allowing commuters to avoid the dense Muslim quarters below. This spatial bypassing reflects a broader politics of invisibilisation and marginalisation of Muslim communities within urban landscapes. |

|

Architecturally, the flyover altered the city’s skyline and disrupted its horizontal urban fabric. Zaidi also noted that it created a new horizon of surveillance over the Muslim ghetto, reinforcing socio-religious boundaries in a city already marked by segregation. Beneath the flyover lies a vibrant yet overlooked cosmopolitanism shaped by working-class Muslim and Hindu communities since the nineteenth century. This rich cultural fabric is often overshadowed by narratives that reduce the area to disorderly or problematic spaces. |

|

|

Today, driving past the J. J. Flyover offers glimpses of minarets and mosque domes reclaiming vertical space, symbolising a subtle resistance against historical erasure—constituting an architectural intervention that is not just about mobility but also about negotiating identity and visibility within Mumbai's contested urban landscape. |

Censorship and the case of Kali Salwaar

Avijit Mukul Kishore

These contestations were further elaborated by filmmaker and cinematographer Avijit Mukul Kishore, who had shot a film, ‘Kali Salwaar’ (The Black Garment, 2002) around these neighbourhoods in the early 2000s. Adapted from stories by Sadat Hasan Manto, the writer who haunted and chronicled the seamier sides of these spaces, Kishore’s presentation converged upon the spectre of censorship that upsets our ability to imagine the lives lived in these neighbourhoods. The graphic novelist Sarnath Banerjee also evoked the presence of ghosts and the overwhelming stimulation Mohammed Ali Road provides for the senses, leading him to develop a narrative to devise ways of consuming the city whole. |

|

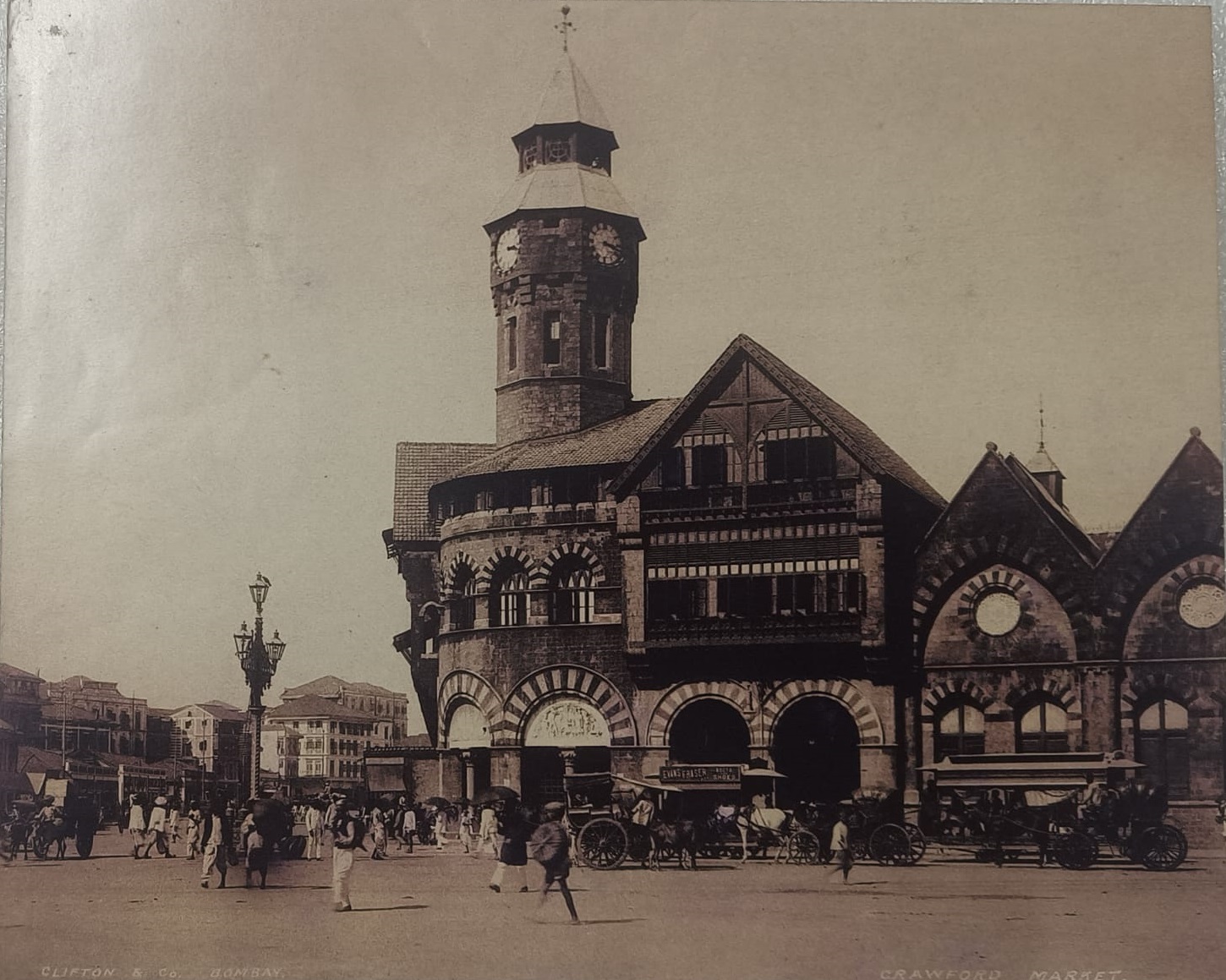

Mohammed Ali Road and Lehri House were pivotal in the artist Tyeb Mehta’s life. Born in Gujarat but raised in Mumbai’s Crawford Market area, Mehta lived at Lehri House (right opposite Mohammedi Manzil) during the Partition riots of 1947. |

|

|

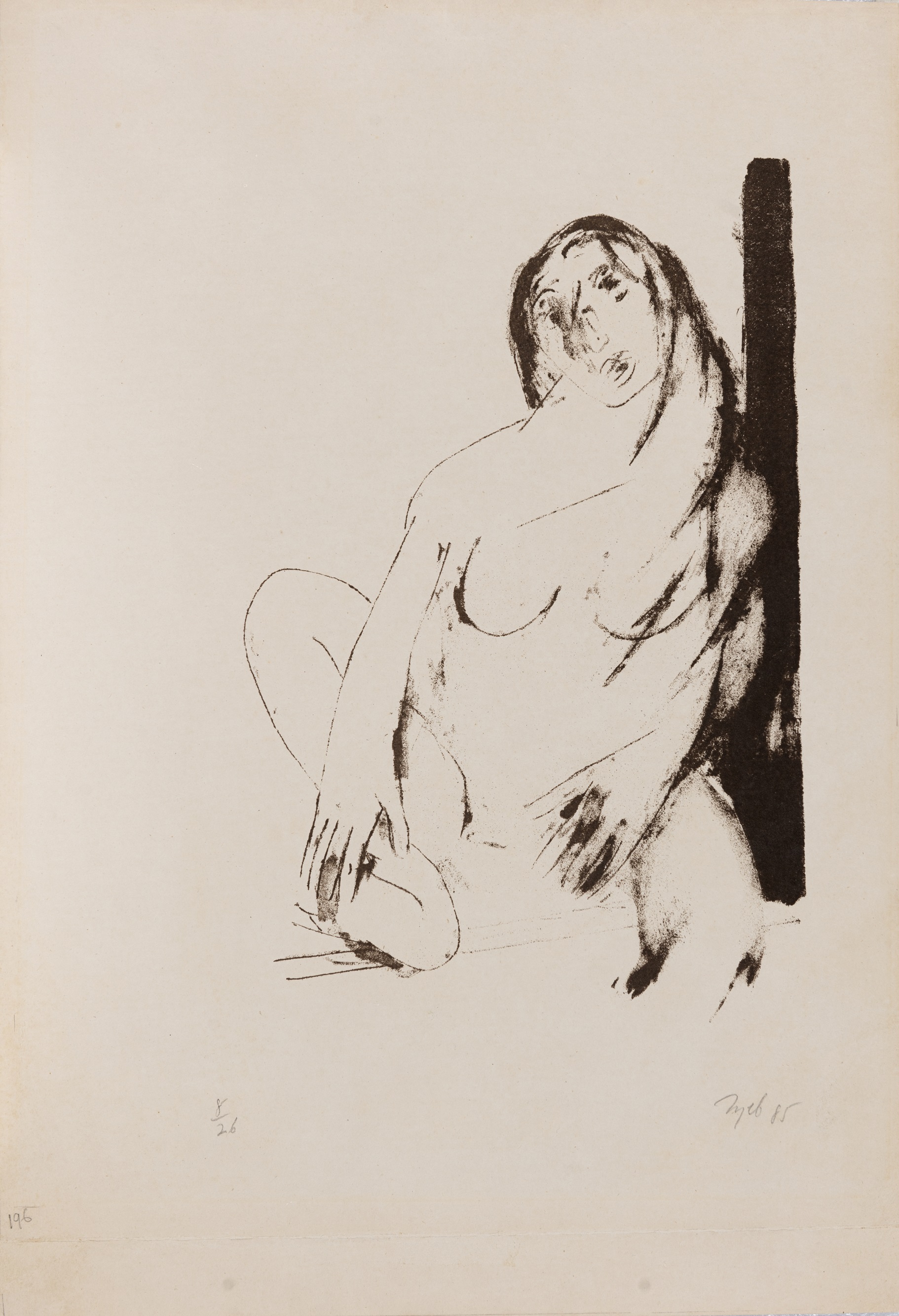

Tyeb Mehta

Untitled

1985, Lithograph on paper, 13.2 × 8.2 in.

Collection: DAG

Crawford Market

Collection: DAG

It was here that the artist witnessed a man being stoned to death by a mob on Mohammed Ali Road—a traumatic event that profoundly influenced his art. Following on from a rise in communal tensions throughout the city, ‘(i)n 1946-1947, riots erupted between Hindus and Muslims… (and) suddenly, Bombay was divided into friendly and hostile zones; Tyeb could not cross the dangerous territory separating his home on Mohammed Ali Road, the city’s distinctive Muslim quarter, to Tardeo, where the Famous Cine Laboratories (where Mehta was working at the time) were then situated.’ This experience profoundly shaped Tyeb Mehta’s stark and often unsettling portrayals of violence, separation, and anguish, most notably in his Falling Figures and Diagonal Series, where a conception of division and territoriality haunts the configuration of the human subject. |

His works reflect an ongoing struggle to reconcile human suffering with formal harmony, a tension he sought to resolve through his restrained yet forceful compositions. As Ranjit Hoskote observed, Mehta’s figures and fields are ‘interlocked and not separate entities,’ suggesting a continuous dialogue between his fragmented human forms and the landscapes—both physical and psychological—that shaped them. His canvases, with their precise geometry and charged stillness, echo the inescapable connection between personal history and collective memory, shaped by his life in the neighbourhood, from where he eventually started going to the iconic Sir J. J. School of Art nearby. While artistic biographies often gloss over such details of belonging, the discussion at Mohammedi Manzil added several cultural layers to our understanding of Mehta’s practice and feel for cultural space. |

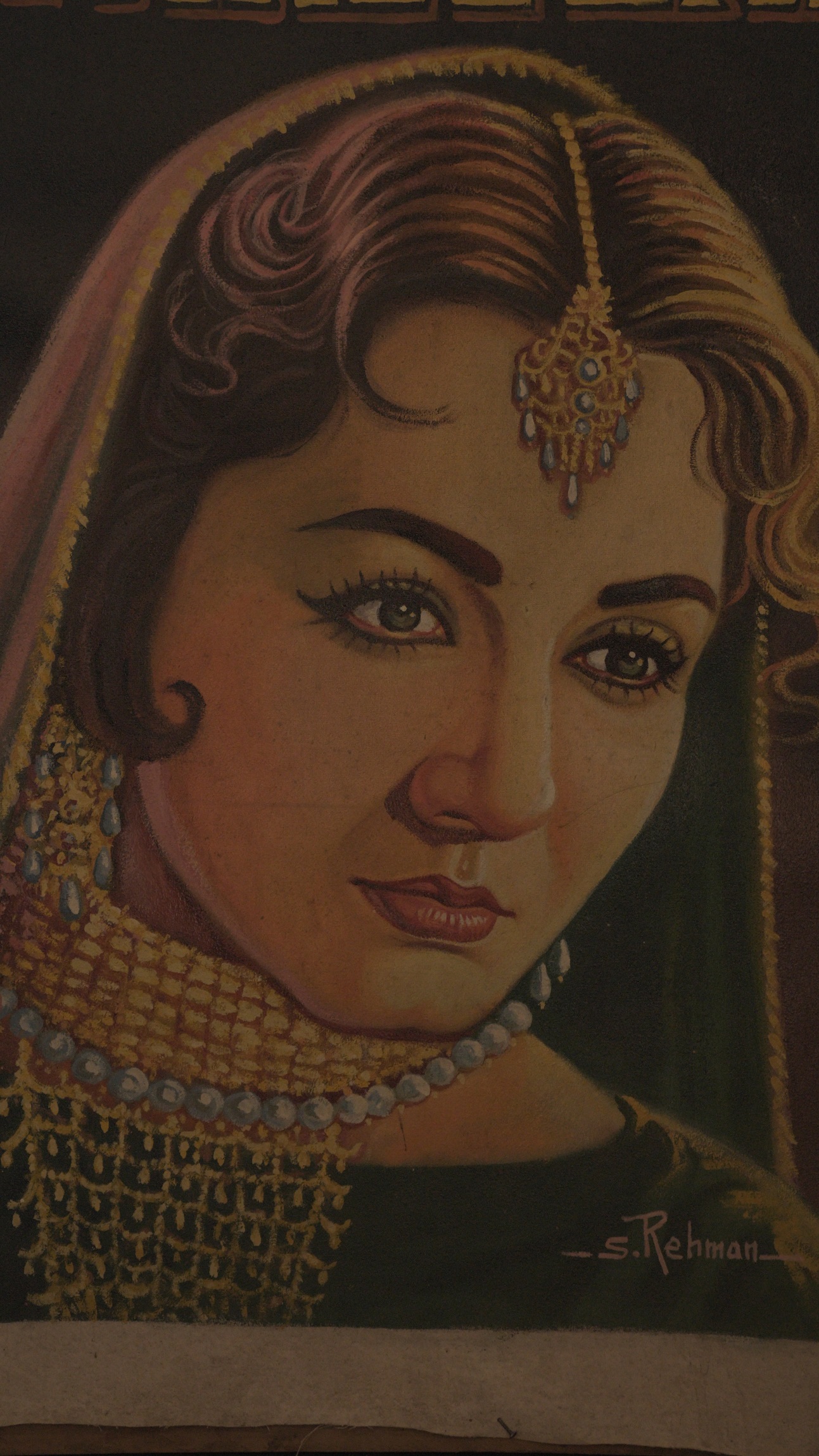

At Alfred Talkies

Work of S. Rehman, resident billboard painter at Alfred Talkies

M. F. Husain

Untitled (Horse and Falcon)

1972, Ink with wax on paper, 13.7 x 19.7 in.

Collection: DAG

M. F. Husain’s connection to Mumbai began at Badr Bagh, near Grant Road, where he lived for fifteen years in a tiny room with his family. Earlier, he had slept on pavements near Alfred Talkies and painted cinema hoardings to earn a living. These neighbourhoods exposed him to the vibrant street life and working-class struggles that informed his art's dynamism. Husain later moved across different parts of Mumbai but retained ties to its bustling streets and cultural diversity. |

|

Both artists drew inspiration from the vibrant yet chaotic urban fabric of these neighbourhoods. Mohammed Ali Road’s cosmopolitanism and its layered histories became symbolic backdrops for their exploration of identity, trauma, and modernity. Their shared experiences highlight how Mumbai’s neighbourhoods nurtured their creative spirits while shaping the trajectory of Indian modern art, probably best experienced by sharing a Bohri thaal on a warm summer evening as the month of Ramadan draws to a close. |

|

|