|

Household Icons Images to Icons: Tracing porcelain dolls in Colonial BengalSoham Raha September 01, 2024 The evolution of popular images in India during the colonial period reflects a complex interplay between global trade, cultural exchange, and socio-economic transformation. This article explores the introduction of German porcelain into the Indian market, particularly its impact on the emerging middle class in colonial Calcutta. By tracing the historical roots of porcelain from its origins in China to its adaptation in Europe and eventual integration into Indian homes, this photo essay examines how these objects became symbols of status, identity, and cultural assimilation in a rapidly modernising society. |

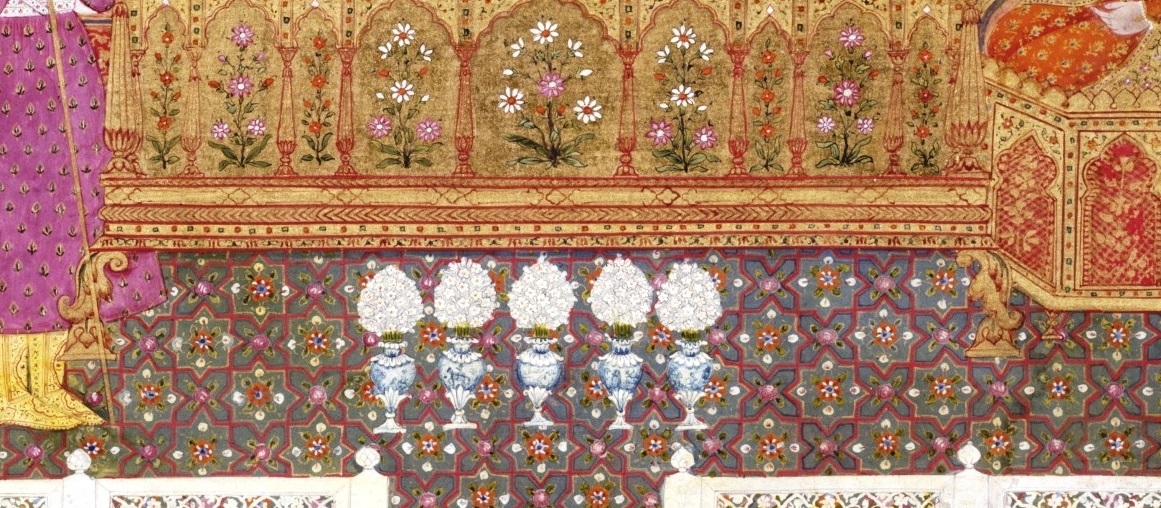

Dakshinakali (detail)

Painted and glazed German porcelain, early 20th century

Collection: DAG

|

'I find it harder and harder every day to live up to my blue china.' — Oscar Wilde |

|

|

Jade bowl carved in Mughal style (with 'Hindustani' decor), China, 1700s, Qing dynasty

Image courtesy: Wikimedia Commons

(Attributed) Khairullah

Shah Alam II (1759-1806), the blind mughal Emperor, seated on a golden throne

c. 1800

Image courtesy: Wikimedia Commons

(Attributed) Khairullah

Shah Alam II (1759-1806), the blind mughal Emperor, seated on a golden throne (detail)

c. 1800

Image courtesy: Wikimedia Commons

The Origins of Porcelain and Its Early Presence in IndiaIndia's contact with porcelain can be traced back to its ancient trade relationships with China. Saleem Ahmad notes, ‘As far as India is concerned, the reference occurs in different parts of the country at archaeological sites, and some literary evidence is also available. India's contact with China has a high antiquity going back into the Mauryan times in the 3rd century B.C. The earliest reference to China is to be found in Kautilya's Arthashastra, which refers to Chinapatta and records the visits of some Chinese travellers like Fa-Hien (AD 399-414), T-Sang (A.D. 629-41), and I-Tsing (A.D. 7th Century) to India.’ During the Mughal period, the use of porcelain was documented by rulers who highly valued it. Babur, in his memoirs, notes that he took a Chinese cup along with him on an excursion. According to the Ain-i-Akbari, ‘Akbar used to have his meals in porcelains of China’. |

|

|

Unknown Photographer

Untitled [British Men Having Tea]

Silver albumen print mounted on card, 1880s

Collection: DAG Archive

European Influence and the Role of the East India CompanyThe European fascination with Chinese porcelain led to its mass importation by merchant trading companies, most notably the East India Company (EIC). According to a historian, 'An important mechanism for the movement of Chinese porcelain was the merchant trading companies that were established in Britain and Europe after 1600. The English company, known as the East India Company (EIC), was responsible for the movement of hundreds of thousands of Chinese porcelains, as well as their distribution in Britain and its overseas colonies.’ |

Barent van Leeuwen

Jug with Silver Mounts

Porcelain with underglaze blue decoration; silver mounts, 24.2 x 12.8 x 11.5 cm.

Image courtesy: Wikimedia Commons

Over the decades, EIC members commissioned porcelains from China, commonly known as armorial ware (porcelains decorated with family or company crests): ‘These objects, though made in China, but the design and patterns and motifs were not Chinese. In simple terms, through their decoration, armorial objects declare both the personal identity of the consumer and ownership of the vessels (and they were almost always vessels instead of figurines). With the armorial decoration, the vessels are no longer anonymous.’ |

|

|

Untitled

Meissen Glazed porcelain plate

Image courtesy: Wikimedia Commons

The Rise of German Porcelain and Its Influence in IndiaIn the early eighteenth century, Europe's first white porcelain was made in Meissen, Germany, under Augustus II the Strong. The Meissen factory often replicated Chinese and Japanese designs from Augustus' collection, heavily influenced by East Asian styles. Johann Gregorius Horoldt, a key painter at the factory, pioneered the Chinoiserie style and introduced vibrant glazes like green, yellow, purple, and brown. He also developed techniques to produce whiter porcelain, enhancing the colours' brilliance. |

Dakshinakali

Painted and glazed German porcelain, early 20th century

Collection: DAG

Unidentified Artist (Kalighat Pat)

Dakshinakali

Watercolour and gouache on paper, c. late-19th century

Collection: DAG

In colonial Calcutta, the newly made class of ‘babus’—an urban elite—responded to the Aesthetic Movement in Britain (1860-1900), and took to the appreciation of porcelain works as well. They began to incorporate German porcelains into their homes. As Jyotindra Jain notes, ‘Like the colonial art schools' lessons in perspective and realism, which fractured the Hindu dreamworld from the mid-19th century onwards, the highly realistic porcelain renderings of these gods, too, cast a spell over the fast-modernizing new middle class of Calcutta at the turn of the century.’ |

|

Between the late 1870s and early 1890s, Calcutta (now Kolkata) and Poona (now Pune) became key centres for printed image production in India. Annada Prasad Bagchi's Calcutta Art Studio, with artists from the Calcutta School of Art, produced religious prints. |

|

|

Saraswati (Ravi Varma Press)

Oleograph on paper

Collection: DAG

Saraswati (Ravi Varma Press)

Oleograph on paper, c. 1900s

Collection: DAG

In 1878, Vishnu-Shastri Chiplunkar's ‘Chitrashala Steam Press’ in Poona published prints of deities, Peshwas, freedom fighters, saints, and educational charts. Inspired by European practices, Raja Ravi Varma established his Fine Arts & Lithographic Press in Bombay (now Mumbai) in 1894, importing German machinery and employing expert lithographers like Fritz Schleicher. The press, later known as Ravi Vaibhav F.A.L. Press, moved to Ghatkopar in 1898 and then to Malavali near Poona in 1901. |

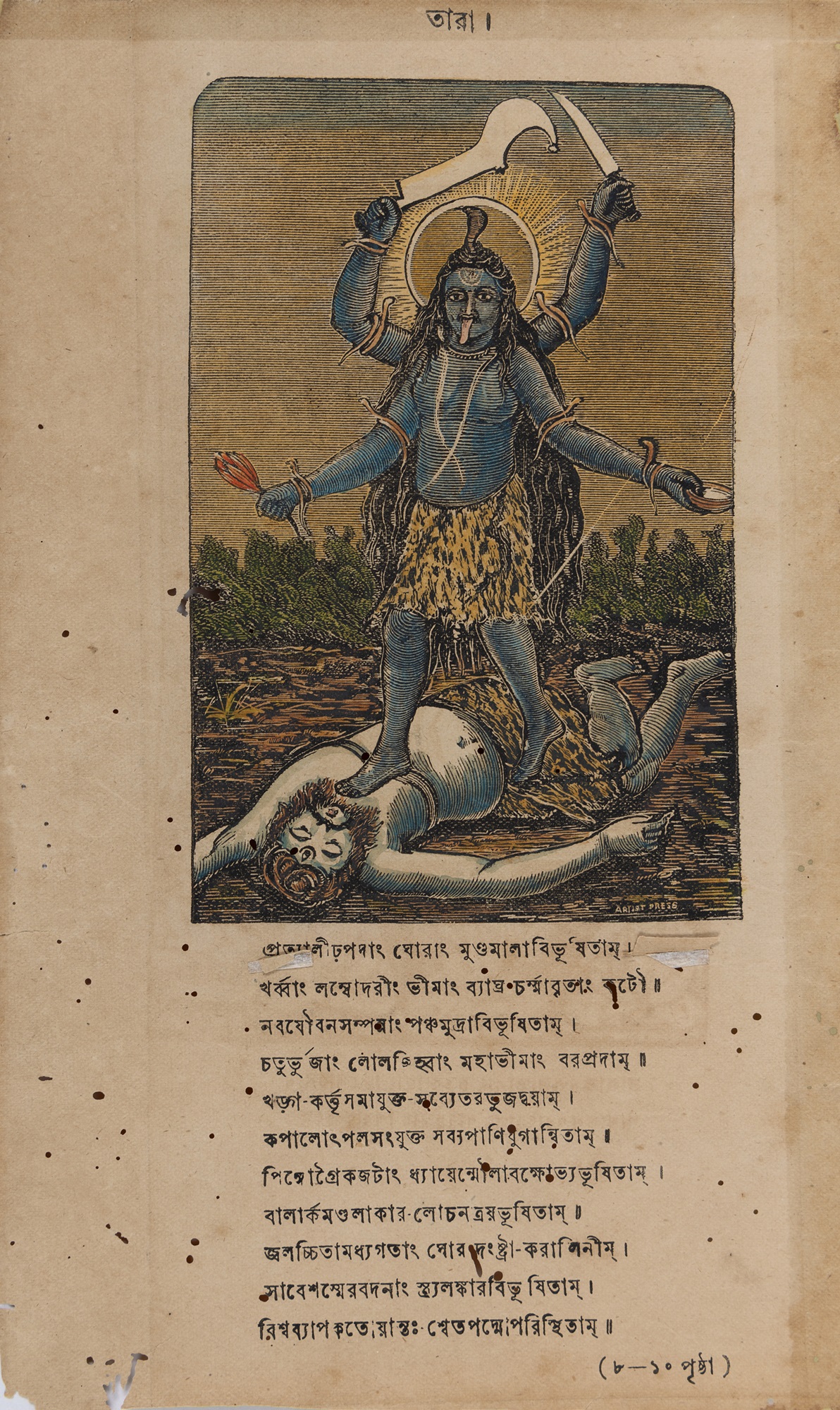

Tara

Wood engraving tinted with watercolour on paper, 1880-1900

Collection: DAG

After the advent of Kalighat paintings, mass-produced iconographies became widely available as souvenirs for pilgrims, collectibles for some, and objects of worship for others. Historically, daily worship in India primarily took place in temples. However, as these images became more accessible to the general public, the practice of visiting temples every day for the sake of ‘darshan’ was being checked among certain sections of society where people began keeping these images at home for worship instead. This shift became more pronounced with the introduction of printmaking techniques by the British in colonial India. German lithographic prints, inspired by popular images, eventually led to the creation of porcelain dolls. Over time, the way deities were worshipped also evolved. In Bengal, for instance, many 'Tantric' deities, once worshipped outside the home, gradually found their place inside. Fearsome goddesses commonly known as ‘Ugra’, particularly Dakshinakali and other Mahavidyas, became less associated with fear and more with compassion, as people began to see these deities as representations of their own 'Mother.' |

|

|

Krishnakali Mata

Painted and glazed German porcelain

eartly 20th century

Collection: DAG

Kali-Krishnamata

Lithograph tinted with watercolour on paper, c. 19th century

Collection: DAG

Manisha Nene writes, ‘The Company B. Rigold & Bergmann, (1895-1916), was listed in the 1910 Directory and Chronicle of The Hong Kong Daily Press Office, as merchant and commission agent having offices at London, Calcutta, Bombay, Delhi and Lahore. This Company produced and distributed picture postcards with Indian themes, lithographs and porcelain figures on Hindu religious themes... Due to advancements in printing technology, porcelain making and textiles, several British firms tried to procure German products to supply to its colonies, especially India. It is important to note that the German printers mass produced the pictures of Indian Gods for their British Clients who in turn employed them in the form of packaging and labelling a variety of goods like oils, soaps, and food as exports to India. These German porcelains were expensive and were not affordable for those outside aristocratic families. Some of them found were especially commissioned by some individual families ‘Calcutta Notes of 19th November 1980 mentions porcelain figures of Kali, Durga, Sarasvati, Ganesha, Annapurna and Shiva Parvati. Two of them – Kali and Durga – have stamps of ‘B. Rigold and Bergmann, made in Germany and mention London. It is mentioned that two of these porcelains were made for Sri Ganga Charan Das.' |

Indistinct branded trademark from a verso of German porcelain figure

Collection: DAG

Tara

Painted and glazed German porcelain

Collection: DAG

A notable type of lightweight porcelain, often referred to as ‘paper-light’, has been produced in Germany. These pieces are distinguished by their multi-coloured bisque firing and glazes accented with gold and silver ornaments. What sets these glazes apart is that they remain fresh and have not discoloured over time. These German porcelain figures typically bear a branded trademark on the back. |

Saraswati

Glazed porcelain, c. 1900s

Image courtesy: Soham Raha

In the later part of the 1900s, a new phase began in doll production with the introduction of porcelain dolls, commonly known as 'Chinamatir putul' or 'Chinamatir murti' in Bengali (Chinese clay dolls). These dolls were priced significantly lower, roughly a third of the cost of those produced by the earlier mentioned factories, making them accessible to a wider audience. Interestingly, while some of these porcelain dolls were displayed as decorative items, a few were also worshipped in certain households. Historically, it's noteworthy that Hindu tradition generally did not involve worshipping baked clay idols. The belief was that idols should be sculpted directly from natural materials like clay, wood, metal, or stone. These materials were thought to possess inherent qualities and energy properties essential for the proper consecration, or 'Pranpratishta,' of the idols, according to the principles of these iconographies, allowing the deity's presence to be fully manifested during worship. |

|

The journey of porcelain in colonial India is not merely a tale of aesthetic exchange—it reflects larger power dynamics and cultural trends of the time. As German porcelain infiltrated Indian homes, it was not just a luxury but became a symbol of colonial influence, subtly altering traditions and reshaping identities, as well as the practices associated with devotion or worship itself. This prompts us to wonder: How do the objects in our lives today continue to carry the weight of history and the implication of global networks in shaping local styles? |

|

|